Chapter 16

First Day: Improving Intonation

In This Chapter

![]() Knowing why intonation is a good opening gambit for a new course

Knowing why intonation is a good opening gambit for a new course

![]() Showing features of intonation visually on the board

Showing features of intonation visually on the board

![]() Teaching intonation to upper-intermediate students using rhymes and flashcards

Teaching intonation to upper-intermediate students using rhymes and flashcards

Good pronunciation is critical to effective communication. No matter how accurate a student’s grammar or vocabulary is, she’ll be met with quizzical looks if what she says doesn’t sound English.

Pronunciation teaching in general is a great first day topic for students because it tends to be an overlooked area, grammar and vocabulary taking precedence. Non-native speaker teachers are sometimes less comfortable with this aspect of the language due to their own accents and a lack of access to authentic communication in English. But no teacher should overlook this area because students are hampered in their learning if they find that no one can understand them when they speak.

In this chapter, I look at one aspect of pronunciation: intonation. You can add meaning, emphasis and emotion, or differentiate a sentence from a question, simply by controlling the way your voice rises and falls. And on top of that, teaching intonation is great fun too!

I show you how to use intonation with all classes, but concentrate mainly on higher levels. Upper-intermediate to advanced students are often jaded and reach a plateau because they feel they’ve studied all the grammar and already comprehend well. Actually, intonation helps students to use what they already know far more effectively, giving them a new perspective on their learning. Hopefully, a look at intonation gives learners new energy as they begin your course.

This first day lesson gets students exploring the way different attitudes and emotions alter the way you vocalise sentences. It increases awareness of how the way you say things influences the listener as much as what you say.

As with all first day lessons, introduce everybody to each other at the outset.

Lesson overview

Doing a warmer activity

![]() , then

, then ![]() 5 minutes

5 minutes

Prepare some flashcards displaying a range of emotions. Choose emotions that you express with adjectives and that students can act out visually.

When you have everyone’s attention, say ‘Good morning!’ (or the appropriate greeting for the time of day). Keep repeating the greeting slowly, but each time hold up a different flashcard and use the corresponding intonation.

Now switch and hold up the cards while you stay silent. Elicit the greeting chorally (whole class together) and see what kind of intonation they come up with. Then elicit greetings from individual students too. Figure 16-1 shows examples of some flashcards.

Figure 16-1: Flashcards showing emotions are useful for eliciting a change in intonation

Using a sound to replace a real word

![]() 6 minutes

6 minutes

The students are going to practise ‘words’ that have little or no meaning without intonation. Write ‘uh huh’ and ‘uh-uh’ on the board and elicit the pronunciation. Ask what these very similar sounds mean; for example, ‘yes’, or ‘I’m listening’ for ‘uh huh’ and ‘no’ for ‘uh-uh’. Put ‘oh’ on the board and say it with different kinds of intonation such as surprise, disappointment, excitement and interest, Ask students what they think ‘oh’ means each time.

Tell the students that you will now speak to them, but that the only response they’re allowed to make is ‘oh’, ‘uh huh’ or ‘uh-uh’ (using the appropriate intonation). Throw out a range of sentences/questions that require agreement, disagreement, acknowledgement, and anything else ‘uh huh’ might mean in natural speech. For example, say:

- Can you lend me £200?

- Would you mind passing this to him?

- If you are 30 minutes late, you can’t come into the classroom.

- You’re Mexican, aren’t you?

- You’re Lorraine, right?

- I’m only twenty years old.

Listening with relish

![]() 6 minutes

6 minutes

Practise ‘oh’, ‘uh-uh’and ‘uh huh’. Divide the class into pairs. Student A has to tell Student B all about an activity she particularly likes doing and one she hates. Student B must listen intently and demonstrate by saying ‘oh’ or ‘uh huh’ in appropriate places and with suitable intonation. The two then swap so that Student B talks and Student A responds. The listener must not remain silent.

![]() 2 minutes

2 minutes

Have a brief feedback session in which one or two students relate what their partners told them. You and the whole class respond with ‘oh’ and ‘uh huh’ in all the right places.

Dialogue building

![]() 4 minutes

4 minutes

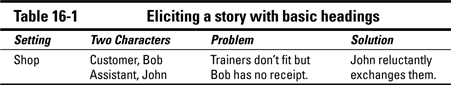

Tell the students that they’re going to create a dialogue together and then use it to practise intonation. Put four headings that help to elicit a story on the board and elicit the content of each section from the students. Table 16-1 shows you how to begin eliciting a story with basic headings

![]() 15 minutes

15 minutes

Break the students into small groups and ask them to discuss and write down a dialogue of 8 to 12 lines using the notes you have elicited. Five to six minutes should be sufficient for this part of the task.

While the students are preparing the dialogues, put a scale of emotion on the board like that in Figure 16-2 (which is advanced level, but you could make it easier).

Figure 16-2: An emotion scale.

After the dialogues are ready, each group must act theirs out but in the manner of one of the adjectives from the scale, which another group dictates. They can choose one emotion for each character. For example, Group A is ready to act and Group B asks for the group members to play Bob as a distraught character and to play John enthusiastically.

Giving student feedback

![]() 5 minutes

5 minutes

After each group has had a turn or two, select a few lines from one dialogue for analysis. Put the lines on the board and elicit the normal and natural intonation. Make sure that key words stand out and that the students sound fluent and polite.

Reading the rhyme

![]() 5 minutes

5 minutes

Select a children’s rhyme that has a sufficient number of lines to share, perhaps twenty or more, and preferably a narrative that the students can follow. I like to use these:

- Jack Spratt

- The Owl and the Pussy Cat

- There Was an Old Lady

- This Is the House That Jack Built

Read the poem aloud so that the class can hear the rhythm that is created by intonation.

Get the students to repeat each line after you. You can also help them to ‘see’ how the rhythm works. Write a line of the poem on the board and highlight the key words. that carry more stress. This helps the students to recognise that the less important words are pronounced in a quicker, more contracted way. In this way the students won’t try to say every word and syllable with equal stress. Doing so just interrupts the rhythm.

You can also show on the board how to break up a line into chunks, each with a falling tone on the final word of each chunk.

The owl and the pussy cat / went to sea / in a beautiful pea green boat

![]() 10 minutes

10 minutes

The students read the rhyme one line at a time around the class. The aim is to keep the rhythm and intonation going from person to person.

If possible, record the students’ reading and play it back to them so that they can compare it to your version. Discuss what they need to do to make their reading more similar to yours.

Doing a cooler activity

![]() 4 minutes

4 minutes

Procedure: Put this sentence on the board (without punctuation):

I’m telling you right now I’m ill

Get students to read this sentence in as many ways as possible while attempting to change the meaning each time.

Extension activities

Try these activities:

- Give students a poem or nursery rhyme to practise at home. They must then recite it to the class (or to a group, if the students are many in number).

- Use an extract from a speech for intonation practice too (then you combine reading and discussion of the events that inspired it). Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech is the obvious choice for most teachers, but how about some movie speeches? The website www.filmsite.org/bestspeeches.html lists a staggering number of speeches and monologues. Give students a homework challenge to select a monologue from one of their favourite films to recite. Perhaps the others could guess which film it is and then watch the real clip.

- Watch a clip from the iconic film ‘My Fair Lady’. Professor Higgins’ use of the xylophone to teach ‘How kind of you to let me come!’ always gets my students repeating and analysing their own speech.

- As a revision activity, use the word ‘really’ as you use ‘uh huh’ in the earlier activity ‘Using a sound to replace a real word’. Get students to respond to conversation with surprise, boredom, disbelief, and so on using this one word.

Ask the students to compare a word/sound in their native language that requires a particular kind of intonation to make the meaning clear.

Ask the students to compare a word/sound in their native language that requires a particular kind of intonation to make the meaning clear. Depending on culture, one person’s respectful silence might come across to another as a lack of interest. Really encourage active, but non-intrusive, listening.

Depending on culture, one person’s respectful silence might come across to another as a lack of interest. Really encourage active, but non-intrusive, listening.