Chapter 3

Getting Down to Planning

In This Chapter

![]() Knowing what to keep in mind before you start to plan

Knowing what to keep in mind before you start to plan

![]() Making a plan to cover a week’s material

Making a plan to cover a week’s material

![]() Incorporating the most important elements of a lesson plan

Incorporating the most important elements of a lesson plan

![]() Seeking inspiration from different approaches to lesson planning

Seeking inspiration from different approaches to lesson planning

When it comes to actually teaching a class, you’ve many considerations to ensure you do a good job. Even when you think you some have great lesson content in mind, you need to ask yourself

- Why am I teaching this language point?

- How does it fit into the course?

- What should my lesson planning include?

- In what order do I present what I want to teach?

Before you start your teaching you need to do some decent paperwork to make sure that your lessons are thorough and organised. A weekly plan and a lesson plan, as explained in this chapter, helps both you and your students see that you’re covering all the necessary elements, ultimately benefitting both you and your students.

In this chapter, I take you through the nuts and bolts of organising your lessons, from working with the syllabus to establishing weekly plans and individual lesson plans. I also take you through several approaches to lesson planning that can inspire your own organisation.

Establishing and Sticking to the Syllabus

A syllabus is a document outlining the things that are going to be taught during a course, in what order and over what period of time (the duration of the course). The syllabus helps to ensure that the course has set aims. Usually, academic managers and experienced teachers prepare it based on the contents of a chosen course book or the specific needs of a group of students.

Sometimes, you may be tempted to deviate from the syllabus because you have good ideas about lessons you want to teach which are not included in it.

So why stick to the syllabus? Here are three good reasons:

- You make sure that your classes cover the breath of material required; no gaps or repetition.

- Your course content is specifically organised so that the class learns X before they can Y. So if a student whines ‘Why can’t we learn about … ?’ you can explain that that point belongs to a different course or level.

- If you happen to be off sick or on holiday, another teacher can fill in for you by following the syllabus structure.

True, a syllabus might sometimes feel like a constraint if it’s a poor fit, but at least you have a framework to negotiate with.

But what do you do if you’d prefer a different syllabus? Well, if you are working for a school, you can inform the school’s managers so that they can adapt the syllabus for next time, or if the syllabus is based on a course book then you can suggest a different one.

Designing Weekly Plans

After you know your syllabus, the next step is to divide it into manageable parts. Now you know what you have to teach, you need to work out how much time to spend on each topic. You do this by making a weekly plan first, and then individual lesson plans (see the next section).

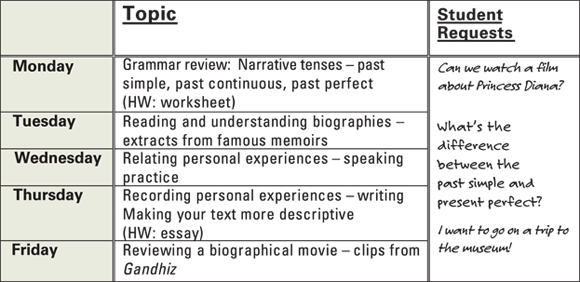

A weekly plan is very much like a mini syllabus. In some schools, teachers have to post their weekly plans on the classroom wall for the students and managers to see. School authorities and inspectors usually consider this to be best practice.

The weekly plan works for classes you teach more than once a week (a monthly plan is effective if your lessons are more widely spaced). Consider some of the benefits of the plan:

- The plan assures students that you are organised enough to think ahead about their learning.

- Students are reminded that the course has structure and that they need to keep up with the pace of learning because they can see when you are going to teach the next topic which is likely more challenging than the present one.

- Your plan can include a space for students’ to request topics they want you to teach them about or questions they want you to answer. For example, they might write a request for another lesson on the present continuous tense because they are not clear how it differs from present simple tense. If students ask ahead of time, you can then prepare well to answer questions they write on the plan and allot an appropriate amount of time to dealing with them.

- It helps you to avoid going off piste too much, because it’s easy to be so distracted by questions and topics that arise in the lesson that you spend too much time dealing with them and forget that you need time to teach other important things. The syllabus reminds you of all the things you ought to cover and that helps to put you back on track.

- You can use it as a revision tool at the end of the week. Look at the things in the syllabus you have covered and test the students to see what they can remember.

- You can see how well you are balancing out the skills focus (reading, writing, speaking, listening) because it is all set out in the syllabus making it easier to allocate appropriate time to each one.

- The plan makes it easier to determine when to set homework and collect it in, So you spread longer, more detailed homework assignments evenly across the course and indicate these on your syllabus. In between these, you set easier tasks so that you have enough time to mark written work and so that your students are not overloaded

If you’re worried that by having a weekly plan your lessons will lack spontaneity, just don’t fill your plan up too much. Make it a general guide for each day rather than a detailed list. In that way you can still tweak your daily lesson plans. Figure 3-1 gives you an idea of how a weekly plan may look.

Figure 3-1: An example of a typical weekly plan on display in my classroom.

Making Effective Lesson Plans

Your weekly plan (see the preceding section) gives you an idea of what you want to teach each day. Now it’s time to get down to the nitty gritty and put together lesson plans.

At the beginning of your teaching career, and when you’re being observed by another professional, your lesson plans need to be very clear and detailed. At times planning can take you hours! However, it’s easy to get nervous and forget your excellent ideas when you’re actually up there in front of the class, so good notes are invaluable. As you mature as a teacher, you develop your own shorthand for putting lessons together. I must admit, though, even after many years in TEFL, I still get to the board on a bad day and wonder what I’m doing there, or simply draw a blank on how to spell the word I want to teach. Embarrassing! That’s why lesson plans are an excellent support.

The following sections outline what you need to include in your lesson plans (for more information on lesson plans, take a look at my book Teaching English as a Foreign Language For Dummies, published by Wiley).

Setting out aims and objectives

The topic of aims and objectives comes up a lot in the field of education. So the first question is, what’s the difference between the two?

- An aim is an overall idea of what you want to achieve. In the course, your aim is always to improve your students’ language proficiency. The course may also help them pass an exam or prepare them for a particular event, such as a job in an international company. At a lesson plan level, your skills-based aim might be to increase reading comprehension or to balance a student’s spoken accuracy with fluency.

- An objective is to do with how you’ll get students to achieve the aim. Objectives are more specific and require various procedures. So if the aim is for students to raise their score in the writing part of an exam, a lesson objective may be to analyse the differences between formal and informal language in letters. Or if the aim is to increase spoken fluency, an objective is to learn more conversation fillers, such as it’s ‘on the tip of my tongue’.

Most of the time, aims and objectives are bundled together. For your lesson plans you simply need to think about what the students need to be able to do better by the end of your lesson, with the syllabus in mind. Thinking about the aim and objective prevents you from simply teaching the students about your favourite topics or just having a laugh with them. (It’s not that you can’t have fun – after all, students learn better when relaxed – but that’s the primary aim of an amusement park not a language school.)

Write your aim(s) and objective(s) at the top of the lesson plan so that you know why you’re doing what you’re doing. As well as writing the overall lesson aims and objectives, you may write them for each main activity also.

Listing the procedures

When you’ve worked out what your students need to learn, you need a variety of activities to help them grasp and practise the points you make. You plan each procedure in advance, paying attention to content, timing and who’s involved in the activity.

And even if you decide to use a ready-made lesson plan from this book, a course book, or a teaching website, you need to put your personal stamp on it, otherwise you come across as rather dry and stilted.

Here are some pointers to keep in mind when setting the procedures:

- Analyse the new language point. As I show in the section ‘Looking at Different Ways to Plan Your Lessons’, later in the chapter, you can call it the presentation, study, clarification, or teach stage, but you must have a part of the lesson that gets technical about the new language point that you’re teaching. You need to go to the board and explain all the rules involved so that students know how to use the new point with minimal errors.

- Don’t overload students! Work out what the students need to know to achieve the objective(s). How much will they be able to absorb mentally rather than just write down? Your answer determines the right amount to teach. Generally speaking, seven new words or one new grammar point per lesson is enough.

Find a link between the new information and what students already know so that learning is progressive. For example, you only teach your class how to describe patterns (stripes, checks, spots) after they know colours and clothing vocabulary well. Don’t jump from the easy to the difficult in one huge leap. Your learners won't jump with you!

Find a link between the new information and what students already know so that learning is progressive. For example, you only teach your class how to describe patterns (stripes, checks, spots) after they know colours and clothing vocabulary well. Don’t jump from the easy to the difficult in one huge leap. Your learners won't jump with you! - Establish a context. Embed the language point into a natural setting. The students need to know why this information is useful. For example, if you’re teaching the past continuous, the context could be explaining why you couldn’t answer the phone (‘Sorry! I was washing my dog when you called.’).

- Check understanding. Think of concept check questions at every stage to make sure that the students understand what you’re telling them. So if you’re teaching items of clothing you could ask ‘Do you wear socks on your head?’ ‘When do you wear gloves?’ or, while holding up an item, ‘Are these trousers?’ Do the same for instruction check questions. Check that students know what to do before they begin a task. (For the lowdown on concept check questions and instruction check questions, see the nearby sidebar on them).

- Practise to make perfect. Think of ways to give your students practice so that they can get used to the new language point in a controlled environment. They’ll make some mistakes at first, but then you correct them and give them another try with a different but related communicative activity.

Balancing the interaction patterns

As you know, a good TEFL lesson isn’t a lecture. You can’t just stand in front of your students and talk at them. Rather, you have to mix it up. So sometimes you talk to students, sometimes they talk to each other and at other times they talk to you, not to mention a bit of silent contemplation in between. These are called interaction patterns. Consider how often the dynamic changes during the lesson according to your plan, and make sure that the students get enough practice doing activities and that there is sufficient variety to keep it interesting.

It’s easier to analyse the balance of interaction patterns in your lesson plan, by putting abbreviated terms next to each activity you plan. Most teachers write something like this:

|

T = teacher |

St = student |

|

Gr = groups |

Sts = Whole class |

So St–St means that one student speaks to another in a pair. T–Sts means that you talk to the class, and so on.

Use the terms that you prefer but make sure that you clearly indicate them on your plan and that they’re easy to understand if somebody else is observing your lesson and following along.

Timing the activities

One of the most challenging aspects of lesson planning is predicting how long an activity will take. It’s never an exact science. Do make a guess, though, and write the estimated number of minutes for each activity on your plan.

Preparing to finish too soon

Just in case a ten-minute discussion turns into a three-minute chat, I suggest you over-plan. By that I mean having extra optional activities at the ready.

For example, if you want the class to talk about and compare national dishes, start off by setting an individual activity during which the students can get their dictionaries out and prepare information. By the time they have to speak they will feel more secure.

Planning for an activity to overrun

Decide how important each activity in your plan is. Be aware of the activities which you can remove without leaving students confused. For example, cooler activities at the end of the lesson can be dropped if necessary.

Factoring in student information and possible pitfalls

All teachers want their students to succeed. Students feel more confident and accomplished if they do well in the lesson, and you as teacher enjoy a sense of satisfaction and can move on to the next teaching point knowing that you’ve built a good foundation. However, in order to enjoy success you need to think about possible hindrances that the students might face. Note possible problems at the top of your plan and write in strategies for dealing with them.

So what kinds of problems do you need to foresee and prepare for?

- Age and background: Your learners will most probably get bored if the material they’re supposed to cover has absolutely nothing to do with their own lives. You might have to adapt or substitute it.

- Equipment: If you’re depending on the Internet or a DVD player to pull off your lesson, you need to test the equipment out before you begin and have a back-up plan just in case it fails.

- Environment: Do you have the space and appropriate layout to do the activities you have planned? And think about the noise levels. Is it okay to make noise in your classroom, or on the other hand, will your silent reading/writing activity be disturbed by any exterior noise?

- Knowledge gaps: Are you sure that the students have enough information to complete the tasks? If some have been absent, you may need to do some revision first.

- First Language interference: You know where your students are from and the language(s) they speak. Make notes about the errors they are likely to make and how you will help them overcome these in your plan. For example, what do people from their culture(s) usually do when they speak English that marks them out as being a non-native speaker? Perhaps they mispronounce a particular sound, put words in the wrong order or use false friends. (False friends are words that students think they know because they look like something in their own language, whereas the meaning in English is very different. So ‘actuellement’ in French means currently not actually. Students who speak Latin languages especially get very blasé about translating into English, and so you need to watch them!)

- Motivation: The students need the information but they’ll do better if they want it too. What can you do to boost their enthusiasm and engage their minds?

- Personalities: Often more dominant speakers take over the lesson, whereas shy students struggle to handle the speaking activities without extra support. Some students clash or dislike each other and others have special needs. Do some students work faster than others? Think about the pairs and groups you’ll form and prepare ideas for keeping everyone occupied.

Nothing on this list is insurmountable. As long as you think ahead and have a little something in reserve (an extra worksheet, game, or task), your lesson can be successful. And if you’re over-prepared, you’ll probably have more material for the next lesson.

Student information and possible pitfalls are individual to your particular teaching situation. I don’t include them in the lesson plans in this book because you’re in the best position to know what suits your group, and where their strengths and weaknesses lie.

Doing warmer and cooler Activities

Short activities that whet students’ appetites for learning at the beginning of a lesson and round off a session with a bit of fun (students really should leave your classroom with a smile on their faces) are called warmers and coolers. They don’t need to be tied into the lesson topic and can be as simple as a game of ‘I spy’ or a general knowledge quiz.

Write a warmer into all your lesson plans. Doing so helps you avoid the frustration of students straggling into the lesson and delaying the start of the main teaching. Have the cooler ready just in case the lesson finishes earlier than you expected.

Reviewing the Hardware

The preceding sections focus on the notes you (and an observer) will see. Now I consider what the students will see and what to bear in mind when planning this aspect of the lesson.

Practising board work

Practically all classrooms have a board, be it white, black, or interactive. Although I only refer to boards here, the principles apply to PowerPoint presentations or other media for displaying information to students.

What you put on the board goes down in your students’ notebooks and is preserved forever (or for a very long time at any rate)! In fact, these days some students don’t even write notes; they just take photos of the board.

When it comes to boards, you have two key considerations: visibility and accuracy.

Visibility

Consider the following:

- Rather than thinking of how much you information can cram onto the board, think about what your students can actually see from all angles of the classroom. You probably need to avoid using the bottom quarter of the board just in case someone’s head obscures the information.

- Coloured pens are really helpful for highlighting smaller points, but for general writing only black or blue will do. Other colours don’t stand out enough.

- Think about what needs to stay up on the board throughout the lesson and when to remove other items.

- If lots of information stays on the board, make sure it’s organised and labelled. You may need to box off some points so that they don’t merge with unrelated matters.

Accuracy

Every teacher I know has made an awful gaffe on the board at some point, either by leaving something out, putting things the wrong way round, or misspelling. Minimise errors by planning your board work beforehand.

- Write up a board menu (a list of things you’ll do in the lesson written in the corner of the board) at the start of the lesson so that you and the students can see where the lesson is going.

- Use a simple equation to convey a grammatical point on the board. For example:

- Check which part of speech you are using and write it in brackets next to key vocabulary. For example, here I show the verb, noun and adjective forms of a word.

restrict (v) restriction (n) restrictive (adj)

- Mark pronunciation features such as the stressed syllable or a phonemic transcription for trickier words.

restriction/rɪstrɪkʃən/

- Make sure you designate errors. Strikethrough works well; for example: restriktion.

- Have magnets or sticky tack at the ready for sticking up images or other information.

- Prepare complicated board work before the lesson and then cover it with paper. You can use a tantalising slow reveal tactic as you go along.

Writing and copying worksheets

Although you can present information on a computer screen or even dictate some questions to the students, which saves paper, using worksheets is beneficial too. Here’s why:

- Sharing one worksheet encourages co-operation among students, which facilitates communication.

- You get to differentiate between groups/students by preparing different versions of a task.

- Students can make notes on them. Those who prefer computerised note-taking can still take a picture of the page.

Photocopying from a book

You probably have a main course whose materials the students have bought too. However, inevitably you’ll need extra information from other publications. As a professional, you’re expected to provide the source for anything you photocopy. So before you print off a dozen sheets, write the name of the book and author at the bottom of the page on your master copy.

Designing your own worksheet

From the outset, let me say that time is of the essence when you’re teaching many classes. I’ve seen a great number of novice teachers spend hours designing new worksheets in their enthusiasm for the job, only for their colleagues to say something like ‘That’s just that like an exercise in the English File resource book!’ Do your research first! There’s no need to reinvent the wheel, so only design what you can’t find on the Internet or in a book.

Remember to:

- Take inspiration from the materials already available to you and then adapt what you find to suit your students.

- Save anything you design for future use.

- Set up a bank of shared resources with your colleagues.

Some of the best worksheets I’ve seen I found in the recycling bin next to the photocopier at my school. Most teachers are flattered when you ask them if you can use some of their work.

Preparing additional materials Apart from your plans and worksheets, it’s a good idea to have other materials on hand, so that you can vary your lessons and keep students interested. Most schools aim to make the following available to teachers (even if you’re teaching freelance, you can have a work area like this at home):

- Access to computers for students

- A selection of course books

- A selection of magazines or catalogues (either in English or just for cutting images out of)

- Board games such as Taboo and Scrabble

- Dice, counters, and a timer for homemade and improvised games

- DVDs suitable for student viewing and preferably with the option of English subtitles

- Graded readers, which are small books that are specially designed for students of English and each one states the level of proficiency it is designed to suit, for example intermediate or advanced.

- Posters about EFL

- Realia (some everyday objects for illustrative purposes; see Chapter 5)

- Reference books (dictionaries, grammar books, and so on)

- Various kinds of stationery (card, paperclips, scissors, glue, and so on)

Looking at Different Ways to Plan Your Lessons

Almost every TEFL certificate course makes use of the Presentation, Practice and Production (PPP) method of lesson planning. In recent years, though, other types of lesson planning have become popular, despite the fact that the basic elements are often similar.

I don’t believe that PPP has had its day, but in this section I want to introduce you to four more ways of approaching lesson planning that are a little more flexible.

In this book I draw on all of the approaches below without labelling them. As you become more comfortable with lesson planning you find that you are able able to balance the interaction and activities in the lesson without being tied to one particular model. However, using a planning model is a very good starting point.

The Presentation-Practice-Production Model

PPP is a three-step process:

- Presentation. First you explain the new language items thoroughly using words, pictures, flashcards, or whatever is available to you.

- Practice. You give the students an exercise to do that tests that they have understood but doesn’t require free expression. The focus is on accuracy. These exercises might include gap-fills, multiple choice, or simple sentence construction.

- Production. When the students have demonstrated that they get the idea by their success in the practice exercise, they can engage in a freer writing or discussion activity in which they incorporate what they already knew with the new language items. The focus is fluency and communication.

PPP has good points and bad points. The reason why PPP is taught on so many TEFL training courses is that PPP is an excellent starting point for new teachers. It is a tried-and-tested method that takes the teacher and the students through logical and progressive steps. PPP is based on communicative language teaching and so promotes pair and group work. By the end of the lesson students feel that they can, to some degree, do what the teacher taught them at the beginning of the session.

However, there are a few problems with this method of lesson planning. Unfortunately, although it can be reassuring for the students when the lessons follow a particular routine, eventually the routine becomes far too predictable and consequently boring. In addition, the human brain doesn’t always need to be taught; it can discover information by itself and is excited by doing so. Therefore, PPP lessons inevitably end up teaching students what they already know. Students also have to wait until the production stage of the lesson to express themselves freely and this can be frustrating. That’s why you ought to add a few other planning models to your armoury. In this way, you can adapt your lesson planning to suit your particular teaching situation.

The Engage-Study-Activate model

The Engage, Study, Activate (ESA) model became popular following the publication of How to Teach English by Jeremy Harmer (Longman, 1998). It appeals to teachers because, unlike PPP, you can move around the stages of the lesson. It is also used frequently by teacher trainers:

- Engage. It is important that students are motivated to learn and use the new language items. So the teacher must find a way to lead them into their learning by arousing interest, emotion or curiosity. A fascinating story, unusual photograph, or song can facilitate this.

- Study. During this stage you analyse structure and rules in the language, and give an opportunity for students to make sure that they understand the new items. However, unlike the first stage of PPP, the teacher doesn’t necessarily have to do a presentation. Instead, you can give the students a guided activity to help them learn.

- Activate. Now the learners can put the new language into practice using freer communicative activities such as role plays, games, and debates.

You can also use an EASA model (engage, activate, study, activate) so that students activate the language, then study it closely and try activating it again. This allows them to reflect on their development during the lesson.

The ARC model

ARC stands for Authentic use, Restricted use, and Clarification and focus, but not necessarily in that order. It was introduced in the book Learning Teaching: A Guidebook for English Language Teachers by Jim Scrivener (Heinemann, 1994). ARC is similar to PPP but often favoured because it’s inductive and allows the students to discover language.

Here’s how it works:

- Authentic use: You expose students to the new language items in a context that shows how people use them naturally; for example, a dialogue. The students practise new language items while focusing on fluency, communication and meaning, like the PPP production stage.

- Restricted use: Students follow the pattern of the sentences you’ve already shown them and make new sentences. This kind of practice concentrates on form, testing and accuracy and is similar to the practice stage in PPP.

- Clarification and focus: During the clarification stage you either demonstrate to the students how to use the new language items, explain to them, or help them to find out for themselves. This is somewhat similar to the presentation stage of PPP and can include explanatory diagrams, some translation, and sentence analysis, among other things.

The Observe-Hypothesise-Experiment model

Here’s a planning model that pretty much does what it says on the tin. It’s a scientific approach, and encourages students to notice things for themselves. It’s related to Michael Lewis’s Lexical Approach (see Chapter 2 for more).

- Observe. You present students with material that contains the information you want them to learn about; for example, a reading text featuring a particular kind of grammar. Apart from the new language point, the rest of the text should be quite familiar to the students so that they don’t get bogged down. When they understand the information, you prompt them to notice the new language point and how it is used in the construction of the text.

- Hypothesise. Next the students come up with a theory based on the language point they have now noticed in the text. With your help, they try to establish some rules which they can apply to their own language use.

- Experiment. The class now undertake a task you set which allows them to try out the new language items for themselves.

The Test-Teach-Test model

The Test-Teach-Test approach to lesson planning requires you to think on your feet because you’re not entirely sure which direction the lesson will proceed in. This method is ideal for advanced level classes. Here’s the process:

- Test. You give the students a speaking activity to do that allows for a lot of free expression; for example, a role play. You don’t explain how to do the activity linguistically; you just let the students get on with it. Meanwhile you note down the errors they make and/or record the entire dialogue.

- Teach. Based on the errors the students have made, you now teach them about the important points that need correcting. You can also prompt peer correction, in which the classmates help to correct each other, or self-correction by playing back the recording of the dialogue. Get the students to practise these points.

- Test. You let the students repeat the same activity they started with or another similar one, so that they can use what you’ve just taught them.

Great TEFL teachers know what their students need to accomplish and they lead their students to success step by step, using the syllabus as the foundation. The syllabus is like a learning roadmap that guides everyone involved.

Great TEFL teachers know what their students need to accomplish and they lead their students to success step by step, using the syllabus as the foundation. The syllabus is like a learning roadmap that guides everyone involved. Set a writing homework task on Thursday. The students have time to ask additional questions about it on Friday and you can provide examples to help them succeed. They hand in the homework on Monday, and while they’re concentrating on the reading task or group activity you’ve set them, you get to sit quietly and start reviewing their written work during the lesson (a bit of learner autonomy is good for students). This is an efficient use of your time. Even if you don’t have daily lessons with the same class, you can spread the work out in a similar way.

Set a writing homework task on Thursday. The students have time to ask additional questions about it on Friday and you can provide examples to help them succeed. They hand in the homework on Monday, and while they’re concentrating on the reading task or group activity you’ve set them, you get to sit quietly and start reviewing their written work during the lesson (a bit of learner autonomy is good for students). This is an efficient use of your time. Even if you don’t have daily lessons with the same class, you can spread the work out in a similar way. You’re not allowed to photocopy a whole book in the UK. Schools need a licence to photocopy, and even so, you’re limited to copying a very small percentage of the work. Some publications, such as workbooks, can’t be copied at all. Fortunately, some resource books are designed to be copied. They’re usually spiral bound and A4 size, which is highly convenient. You generally find copyright information at the front of the publication.

You’re not allowed to photocopy a whole book in the UK. Schools need a licence to photocopy, and even so, you’re limited to copying a very small percentage of the work. Some publications, such as workbooks, can’t be copied at all. Fortunately, some resource books are designed to be copied. They’re usually spiral bound and A4 size, which is highly convenient. You generally find copyright information at the front of the publication.