Chapter 5

Mechanisms for Culture Change in Health Institutions and the Example of the Nursing Home Industry

Jane Banaszak-Holl and Rosalind E. Keith

Learning Objectives

- Define culture change in health care as a type of organizational transformation.

- Understand how mechanisms of culture change within the US nursing home industry have been promoted to effect a transformation to resident-centered care.

- Examine mesolevel mechanisms and the role they play in supporting and sustaining the culture change process.

- Consider how communication, leadership, and training practices can foster transformational culture change and evaluate existing gaps in how these processes have been studied.

- Understand various approaches to studying culture change and consider how in-depth studies of organizational processes at multiple organizational levels, using different methodological approaches, may aid in the evaluation of culture change.

This chapter describes in detail mechanisms of culture change that are either studied or prescribed within the US nursing home industry to effect a transformation to resident-centered care. Resident-centered care has been presented in the media as a fundamentally new approach to service in US nursing homes; it is also frequently referred to as culture change because this approach forces staff to rethink and reengineer existing clinical practices. It is appropriate to view this change as a form of more general organizational culture change, because culture change in nursing homes would require widespread or transformational changes in everyday work practices throughout these organizations and as a cultural shift, motivated by shifting institutional values and norms. Consequently, the mechanisms for culture change are fundamentally different from change mechanisms that drive clinical practice changes as described extensively, for example, in recent implementation research (Pronovost et al., 2006; Conway and Clancy, 2009).

Implementation research focuses on how management encourages the adoption of a narrow range of clinical practice changes within units or targeting specific clinical problems. These changes most often do not require staff to rethink how they perform work or shift their understanding of the organization's culture or values. Culture change, however, requires extensive changes in everyone's work practices to realign with the organization's new priorities and goals in addition to extensive coordination of new practices and substantial institutional support, possibly requiring additional resources such as staff or technological support to reflect the new goals of the organization.

The shift to resident-centered care in nursing homes is a type of culture change that is gaining attention throughout health care as the sector experiences institutional pressures for clinicians to address individual preferences for care. Nursing homes provide a unique service that is a combination of clinical care targeting improvements in residents' health and residential care that allows residents to live comfortably with limitations and reflecting their personal choices. The shift to resident-centered care requires attention to both the daily living and the health care needs of the nursing home population, which means that issues common to implementation of patient-centered care may be even more difficult within the nursing home setting.

In the primary care and acute care settings, the shift to patient-centered approaches has included adopting practices that increase patients' involvement in care decisions and are designed to strengthen the patient-provider relationship. In the patient-centered medical home model, for example, these practices include an integrated team approach to primary care delivery facilitated by information technology, evidence-based clinical practices, engagement in quality improvement initiatives, better patient education, and feedback to providers (Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative, 2012; Rittenhouse et al., 2008; Robert Graham Center, 2007). In the chronic care model, these practices include team decision making and improving information provided to patients regarding their health needs (Wagner, Austin, and Van Korff, 1996; Wagner et al., 2001). In the nursing home setting, in comparison, the resident-centered model has led to extensively restructuring daily activities to align better with residents' preferences for when they eat and bathe, an increased focus on personal relationships between staff and residents, and remodeling of facilities to make them more closely resemble residents' home environments (Fagan, 2003; Kehoe and Van Heesch, 2003; Thomas, 2003).

Although the goal in patient- and resident-centered approaches to care is to transform the experience and perspective of those receiving care, successfully achieving these approaches requires transforming the roles and work practices of frontline caregivers, patients' primary point of contact. In all of the current models of patient- and resident-centered care, individual clinicians must have greater flexibility in decisions they make during caregiving so that they can respond to patient preferences in a timely fashion. Furthermore, these approaches require giving priority to resident and patient needs to an extent that conflicts with other priorities, including cost efficiency or clinical quality, forcing nursing staff to make discretionary decisions about resident care. Top management plays an important role in reinforcing through organizational culture that resident- and patient-centeredness is a priority in clinical services and for operations more generally.

Within the nursing home sector, Shaw (2003) has identified a number of major movement organizations that promote resident-centered care through culture change: Eden Alternative, Wellspring, Regenerative Community, and Green House models. Shaw argues that all of these models break from the traditional medical model emphasizing medical treatments and articulate work practices and structural characteristics associated with resident-centered care. The oldest culture change movement, the Eden Alternative, started in 1991 (Thomas, 2003) and now has over three hundred registered facilities across the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia (www.edenalt.org). The Green House Project carries the Eden principles further in the development of environmental design and staffing principles; the most recent culture change movement, it has around forty campuses across the United States (www.thegreenhouseproject.org). The Live Oak Regenerative Communities also represents a small set of facilities with their own core principles for resident-centered care. Finally, the Pioneer Network is a professional network of nursing home staff from across the country who have agreed to advocate for the principles of resident-centered care. These groups provide substantial resources for defining and implementing culture change in nursing homes.

As resources, these formal associations have laid out recommended changes in work practices and implementation tools for developing culture change (Rahman and Schnelle, 2008). Although the movements themselves articulate the larger vision and purpose behind implementation, most nursing homes do not choose to adopt the full culture change model, so membership in culture change groups represents only a very small subset of US nursing homes (Banaszak-Holl et al., 2013). Also, the literature on culture change is rarely connected to theoretical models of how institutions and organizations change and provides little empirical data on when facilities transform into culture change institutions.

Culture change is a type of organizational transformation that includes widespread change throughout an organization (for an excellent example of more general transformational change processes within the VA provider system, see Lukas et al., 2007). However, in many cases, studies of transformational change focus on externally driven improvements in clinical practice, not on transforming the institutional values that support health provider organizations' work practices. Consequently, we define culture change more narrowly as organization-wide initiatives that are motivated by top management's efforts to shift the values or institutional focus of work practices.

In defining culture change this way, we are excluding organizational transformations driven by response to external economic pressures such as payment changes. In recent years, some health care providers have transformed work practices to be evidence based or value driven only because professionals have demanded this or insurers have required increased use of guidelines. This is now occurring within surgical suites where checklists have become predominant because of their public visibility (Haynes et al., 2009), and in hospitals generally, intravenous practices throughout these organizations are changing to reduce health care–associated infections in part because Medicare and other insurers have stated that they would no longer pay for these health conditions (Zhan et al., 2009). In the nursing home setting, regulatory pressures to reduce pressure ulcers may in part be responsible for the widespread adoption of improved clinical treatments for this problem (Zhang and Grabowski, 2004). These changes are driven by outside pressures to implement changes in effective clinical practices and by widespread adoption of new practices among professionals working within health care organizations.

Clinical practice changes have subsequently been supported by insurers' use of value-based payment for services (Fendrick and Chernew, 2006). Value-based design seeks to limit the use of clinical practices that are not cost effective. Culture change, or internally driven transformations, may be responsible for the adoption of new clinical practices among early adopters who do not yet face market pressures or dominant professional logics to change practices. Hence, the study of culture change can be valuable for understanding why some organizations are effective in implementing practices without external pressure to do so.

In the area of culture change, cost effectiveness is more difficult to judge because facilities often combine a mixture of new clinical and work practices during these transformations, and comparisons among other organizations are difficult to find. The evidence from evaluations of nursing home culture change activities has been mixed, in part because each organization adopts a different set of practices (Rahman and Schnelle, 2008). Nonetheless, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare have created incentives for facilities to adopt the culture change practices, providing an institutional and normative incentive for facilities to adopt these practices. The move to culture change in US nursing homes has also been incentivized by some states that have begun to pay for evidence of culture change practices. Consequently, even as external normative and financial pressures such as payment by states to change are being introduced, the evidence for the effectiveness of these approaches is limited and the impact of changing payment schemes unclear.

The Context for Nursing Home Culture Change

The structure of the population in the United States is forecast to change dramatically between now and 2050, with the population over the age of eighty-five expected to increase from 5.5 million to 18 million people (US Census Bureau, 2012). The number of nursing home residents is forecast to increase from approximately 2 million today to 4.5 million in 2050. This rapid increase of the older population will have a significant impact on the organization and delivery of long-term care, especially as the elderly population demands more independence and rejects the institutionalized manner through which long-term care has traditionally been provided. The Nursing Home Reform Act was passed under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act in 1987. The objective was to improve the quality of care that residents of nursing homes receive and ensure that residents are free from abuse and neglect and are receiving adequate care. Such macrolevel factors result in pressures to pursue culture change and resident-centered care practices, thus influencing factors at the microlevel, including the provision of care by caregivers at the front lines of long-term care delivery.

The nursing home industry must change dramatically if the quality of its services is going to improve. Nursing homes are criticized for being unhealthy for employees and residents because of high rates of physical injuries for both parties, high levels of employee stress, unrealistic workloads, lack of administrative supports, and emotional exhaustion resulting from stressful interactions among residents, families, and staff (Eaton, 2000; Kemper et al., 2008). Quality problems related to the persistent use of medications against guideline recommendations (Lau et al., 2004), impoverished facilities operating with persistent low-quality care (Mor et al., 2004), and extremely high levels of staff turnover (Castle and Engberg, 2005) have all been linked to nursing home organizational characteristics.

Nursing home care requires repeated interactions between staff and the residents as customers, and nursing homes are increasingly considering customer relationships as key to the quality of care they provide (Anderson, Issel, and McDaniel, 2003; Zimmerman et al., 2002). In this context, interactions with staff are key not just to providing top-quality clinical care but also to managing the full experience of the nursing home stay. A strong organizational culture can be important for ensuring consistency across the long periods of daily interaction between residents and caregivers and for reducing staff turnover by ensuring that staff understand expectations for how service is provided (Castle, Ferguson, and Hughes, 2009). While resident-centered care is only one type of culture to promote in nursing homes, it provides both consistency and a focus on residents' needs in line with common approaches to customer relationship management.

Culture change could, if it worked, make a significant difference in the quality of nursing home care, and in editorials, culture change in nursing homes is often argued to be a panacea for the woes of our long-term care system. As this chapter was being developed, the New York Times reported on how the Green House movement could transform nursing homes in the following way:

In a Green House, each home is staffed with two certified nursing assistants who perform all of these [needed care] jobs, but for fewer residents. In addition, one registered nurse typically supports two or three houses. “If you have one person doing everything, they can spend more time with the residents and get to know somebody as a real person,” said Robert Jenkens, a director at NCB Capital Impact. (Tarkan, 2011, p. 5)

In other words, in this new model, the work roles of both professional and nonprofessional staff are transformed to shift their emphasis from a medical model to more of a social model for service provision. The desired focus on resident preferences requires fundamental changes in how all staff interact with residents that cannot be achieved by simply hiring different or more staff. It is through the routine interactions between staff and residents during daily clinical and personal care—including encounters with health professionals—that residents are able to express preferences and either do or do not get the impression that they are being treated with respect and dignity and their preferences are taken into account. If residents are treated differently by any of the clinical and nonclinical staff, they may perceive their interests as not being met. Furthermore, clinical interactions have a substantial impact on more mundane interactions by affecting key factors such as residents' pain tolerance and medication use, which will affect residents' ability to communicate and interact with other staff as well as their ability to accomplish routine tasks such as bathing or moving from their room to common areas. Hence, staff must have a consistent and common approach to defining and implementing resident-centered care.

Culture Change as a Form of Organizational Change

As recent turmoil over the changes introduced through the Affordable Care Act has shown, periods of institutional change include normative debates over how care is provided and substantial resistance to new models in the delivery system. Through periods of transformative change, health care providers seek to minimize disruptions to how patients are treated and ensure that quality is sustained. However, disruptions to service and reduced quality are fairly common in such periods of change (Bazzoli et al., 2004a). Research on the mechanisms that facilitate smooth transitions during institutional change may be valuable in health care to ensure that individuals are not hurt by organizational change. This is a critical issue in the nursing home sector, where quality is tenuous at best, staff already face high turnover and low morale, and normative shifts in institutional models of care have been slow to occur.

Evidence shows that the adoption of individual work practices associated with nursing home culture change has occurred more rapidly than membership in the culture change groups or movements. Castle's (2012) recent work shows that some of the work practices associated with culture change have been adopted by as much as 70 percent of facilities, whereas other practices are observed in less than 30 percent of facilities. However, evidence of affiliation to culture change groups is under 20 percent (Banaszak-Holl et al., 2013). These results emphasize that changes at the practice level do not always occur together or lead to organizational transformation. Fundamental shifts in organizational culture are mesolevel changes, which are greater than microlevel changes, in individual work practices.

As institutional theorists have argued for decades (Alexander and D'Aunno, 2003; Oliver, 1991; Scott et al., 2000), broader institutional change can be observed occurring at multiple levels of analysis—macro-, meso-, and microlevels. Macrolevel changemacrolevel change involves transformation of organizational structure and design, and change at the micro-organizational level involves alteration of individual attitudes and behaviors (Staw, 1984). Mesolevel change has been identified as important to integrating macro- and micro-organizational transformation. Mesolevel processes—those that bridge units or groups within an organization—include coordination and communication regarding work practices. They are key to connecting macroinstitutional change (e.g., societal pressures) to individual-level change (e.g., caregiver attitudes and behaviors). Rousseau and House (1994) provide a description of the mesolevel and its importance in integrating macro- and micro-organization theory:

Meso used in the context of research refers to an integration of micro and macro theory in the study of processes specific to organizations which by their very nature are a synthesis of psychological and socioeconomic processes. Meso research occurs in an organizational context where processes at two or more levels are investigated simultaneously. Its thesis is that micro and macro processes cannot simply be treated separately and then added up to understand organizations. (p. 14)

These mesolevel mechanisms are important for uniting individuals within the organization by shaping individual values toward work practices critical to sustaining culture change.

In reviewing the existing literature on nursing home culture change, we have found many articles that emphasize leadership, communication, training, and professional development as important aspects of nursing home culture change. We highlight here how these aspects of management can be viewed as mechanisms that bridge the micro- and macrolevels and facilitate the individual's process of transforming his or her beliefs. We evaluate some of the existing findings on leadership, communication, and professional development, including training, for the relative importance of integration across individual-level cognitive schema and values. Much of the literature is prescriptive and provides in-depth discussion of how these organizational elements support the culture change process, but the literature does not provide a theoretical framework for comparing studies or examining evidence for the generality of the culture change process.

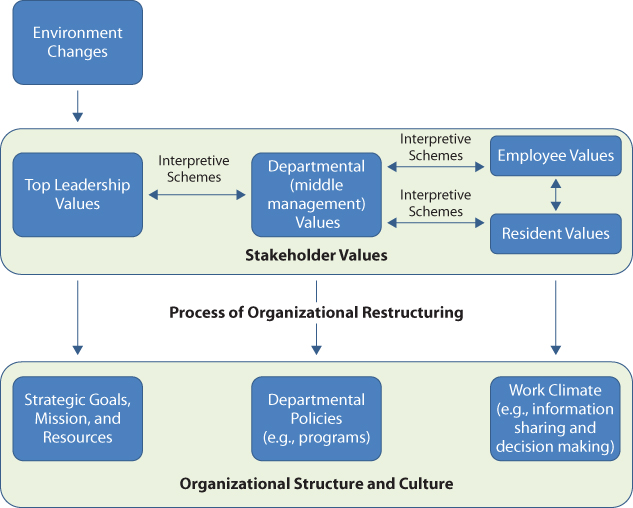

Subsequently, we develop and apply a model first developed by Jean Bartunek to describe normative change within a religious order, in which individuals hold strongly to their own beliefs. Bartunek (1984) argued that during periods of institutional change, individuals' cognitive schema must be transformed in order to change everyday work decisions and practices (see figure 5.1). Individual-level cognitive schema are the lens through which individuals understand their work practices, and periods of institutional change are times when cognitive schema become malleable and realigned.

Figure 5.1 A Framework for Studying Culture Change in Organizations

Organizational mechanisms for transforming work practices, including leadership, communication, and training, may have a limited impact on employee behavior or may fundamentally shift employees' beliefs regarding work. In the case of institutional culture change, behavioral changes are not enough to change work practices; employees may lapse into old practices or even seek work-arounds that incorporate some of their old practices. Leadership, communication, and training are not newly discovered mechanisms for change; managers will tell you they are critical elements of the change management process. We emphasize their unique role as particularly important to culture change. They are essential for culture change because they provide feedback mechanisms for evaluating individual resistance and changing cognitive schema during transformation. Persistent resistance to institutional change can lead to more subtle behaviors that reduce the quality and effectiveness of new practices.

At the same time, we have modified Bartunek's model by explicitly highlighting the negotiation that occurs across stakeholders' values when cognitive schema change (in figure 5.1, we link individuals' value systems through negotiated interpretive schemas). Culturally driven change presumes that individuals incorporate values and value-driven priorities into workplace decision making. For example, in resident care, staff frequently must make choices about what to do for residents given the multiple demands on their time. In resident-centered approaches, residents' requests for snacks outside mealtimes or other common changes in daily routines require staff to rethink the structuring of their other care tasks. Staff may be hesitant to make these changes if there is not a clear organizational priority for a resident-centered approach. A critical element of culture change is then the synchronicity between individual and organizational changes and whether mesomechanisms for change support individual staff members' reflections and actions to change work practices.

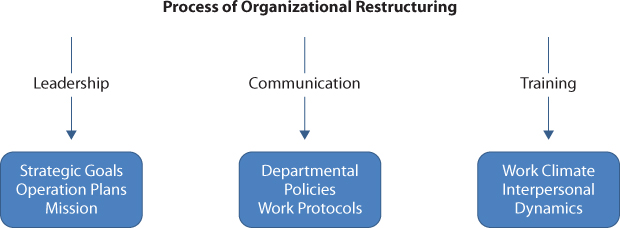

As figure 5.2 emphasizes, our focus here is on how these mechanisms of leadership, communication, and training reinforce cognitive schemas present among staff, patients, and managers and how the subsequent changes in organizational structure and processes also reinforce these cognitive schemata. In other words, employees should respond to effective mechanisms for change not only with new behaviors but with stronger commitment to the values and norms behind care practices.

Figure 5.2 Mechanisms for Culture Change in Health Organizations

In order for an individual's values to influence codified work practices, those values must become espoused and enacted. Organizational research has a long tradition of understanding how cognitive schemas are translated into work practices that began with Goffman's (1961) research on the asylum and Berger and Luckmann's work, The Social Construction of Reality (1966). More recently, Weick and colleagues have explored how individuals need sense making as they learn or unlearn organizational routines (Weick, 1993; Weick, Sutcliffe, and Obstfeld, 2005). In all of these traditions, whether individuals enact personal values in work practices is dependent on the social context and how strong group norms are.

The nursing home context has some eerie similarities to the prisons and mental hospitals that Goffman studied as “total institutions,” in that nursing home staff make judgments about care practices and about residents themselves that shape the residents' daily lives and have an impact on the residents' sense of self-control and efficacy. For example, within nursing homes, staff make critical decisions regarding flexibility in residents' care routines that affect residents' daily activity and may include how long staff spend interacting with residents, whether staff discuss with residents any deeply personal issues that may include emotional or spiritual problems, and whether staff encourage the resident to engage in social activities rather than simply maintaining patterns such as watching TV. Organizationally it is difficult in the long-term care setting to reach clinicians—primary care and specialist physicians as well as nurse practitioners or medical assistants—who are the primary decision makers about pain medications and changes in care routines. Subsequently residents may also experience delays in care that affect their personal lives. In all of the theoretical traditions of social constructionism, an employee's translation of personal values into his or her work routines will be critical to the routine decisions he or she develops for resident care during the workday. Subsequently, daily routine actions are critical points for studying how cognitive schemas are enacted in organizational practice.

While employees may hold strong personal values about how care should be delivered, the facility might not adopt those values for any number of reasons. For example, although facilities may value the time staff spend with residents, they may lack the resources to provide staff time for desired interactions. In addition, competing values may lead staff to promote a care approach that conflicts with their personal values. For example, staff may value integrating residents into social activities, but they may not encourage some residents to become socially engaged if those residents are clinically at risk for falls or other medical problems associated with more mobility. In other words, the value of promoting the functional well-being of the resident may be equally important to maintaining their social involvement in the facility. It is not unusual for staff to compromise in promoting their own personal values if they perceive the compromise as important to meeting the mission and goals of the organization, which is to serve the residents. Hence, transformation of cognitive schemas requires staff to be able to recognize change as a priority and be ready for that change.

Staff may already have values that align with resident-centered care but may not recognize the benefits in espousing those values within the care setting. Indeed, some researchers have found that nursing home staff personally value affective forms of caregiving, both emotional and social, over instrumental forms of support, yet they may become burned out because their expectations for care do not match the care they can provide (Hullett, McMillan, and Rogan 2000). Hyman, Bulkin, and Woog (1993) also found a major tension between employees' personal ethics of caring and the need for professional distance and efficiency within the workplace. In addition, recent literature has suggested that nursing home employees have stronger values regarding caring for others than is found within the general population with regard to approaches to death and dying (Hyman et al., 1993), their ability to use moral reasoning (Sasson, 2000), and their ethical decision-making practices (Holmes and Meehan, 1998; Mattiasson and Andersson, 1995). Processes of change may simply need to highlight to employees the importance of specific values present from their social and cultural environment. Furthermore, as individuals change their work practices, a natural part of the culture change process will be the ways in which employees confront differences in their cognitive understanding of the situation or compare their reasoning to that of other employees who are doing their work differently (Bartunek, 1984; Ranson, Hinings, and Greenwood, 1980). Facilitation of change will include processes for highlighting and openly discussing those differences.

Because consensus building is an important element of reinforcing organizational culture, often research on culture identifies the commonly shared ideas of work practices and ignores evidence important to the tension (e.g., implicit disagreement) and conflict occurring in work practices (Greenwood and Hinings, 1996; Kitchener, 2010). Important aspects of institutional change include studying and evaluating the conflicts among employees, as well as assessing whether and how top management mediates conflict by supporting some work practices over others. Although the traditional leadership role (Barnard, 1938) is to diffuse values to all facility staff and key stakeholder groups (Martin, 2002; Schein, 2004; Denison, 1996; Quinn and Kimberly, 1984), a critical component of institutional change is negotiation among the conflicting values and diffusion of conflict over value priorities. Many of the mechanisms for integrating personal change into organizational transformation, such as through training and development and effective leadership and communication, are viewed as processes through which organizational culture is enforced among employees. They are not seen as mechanisms for negotiation among competing values and interpretive schema.

Finally, we should highlight that we do not discuss empowerment as an integrating mechanism within culture change, even though it is central in the literature on nursing homes. Staff empowerment in and of itself is a goal of culture change (Boggess, 2004; Keane, 2004; Krasnausky, 2004; MacKenzie, 2003; Monkhouse, 2003). However, we believe empowerment constitutes changes in behavior that presume personal beliefs have already been transformed. The concept of empowerment is key in resident-centered approaches to care because employees are expected to use greater discretion in decisions when providing care to residents (Chenoweth and Kilstoff, 2002; Scott-Cawiezell et al., 2004; Mitty, 2005). Indeed, management scholars define empowerment as a process that facilitates an individual employee's initiative to carry out tasks within the context of his or her work environment (Spreitzer, 1996; Thomas and Velthouse, 1990). Culture change research has found that empowered employees are less likely to develop conflicts with residents' families (Davies et al., 2003; Krasnausky, 2004). Indeed, these findings reflect that empowerment presumes that employees' work practices are understood and that there is a facility-wide consensus on how to treat residents.

In this section, we have highlighted the role of identifying and negotiating staff's attribution of values in work practices as a critical element of culture change. This focus leads to an emphasis on the negotiation among conflicting cognitive schemas before an organization can successfully adopt new cultural models for work practices. Whereas research on culture change often emphasizes mechanisms at the organizational level for disseminating values affecting work practices, such as has been emphasized in the safety culture literature, little work has been done on identifying whether staff perceive conflicts in workplace values and how negotiation, both interpersonal and intrapersonal, occurs during the introduction of new cultural values. Indeed, managers rarely discern how much employees experience intrapersonal or internal conflict as they work through their own self-understanding of changing work practices and may discourage reports of interpersonal conflict as they encourage employees to work out disagreements without formally communicating problems.

It is possible that culture change may be enforced through managerial edict, but often, in that case, managers do not always understand the existence or persistence of resistance to changing organizational practices. Our organizational behavior model focuses attention on when and why resistance and conflict occur, because these are critical elements to explaining how fast changes occur and how long implementation will require. This may be part of the reason we still find it puzzling that simple changes take longer in some workplaces than in others. Subsequently, further research is needed on employees' attitudes or perceptions of how the workplace is changing beyond existing instruments of employee satisfaction, which minimize our ability to discriminate whether employees perceive conflict with their own values or among different practices. Clear examples of conflicts in how to conduct work practices are important clues to knowing more generally when employees confront differences in values.

Three Elements of Restructuring: Communication, Leadership, and Training

Mesolevel activities, such as processes of coordination and communication, are used to unite employees in transformational change and influence individual-level attitudes and behaviors. Popular literature on health management highlights how leaders should use such processes and focuses frequently on leaders' stories of transforming the workplace. Managerial textbooks on effective leadership practices also emphasize the importance of transmitting values and communicating the reasons behind change (Banaszak-Holl et al., 2011). Indeed, a focus on transformational leadership has become strong again recently in the organizational behavior literature and highlights the ways in which leaders communicate with and motivate employees (Avolio, Walumbwa, and Weber, 2009).

Transformational leadership is not a new concept, as James MacGregor Burns first proposed the concept in 1978. Transformational leaders use four key methods to influence employee behavior: (1) articulating an effective vision, (2) motivating through inspiration, (3) stimulating the intellect of subordinates, and (4) individualized consideration (Banaszak-Holl et al., 2011). The key founders of the nursing home culture change movement, such as Bill Thomas at Eden Alternative, have highlighted their own roles as transformational (Thomas, 2003). Hence, the use of communication, coordination, and leadership practices is frequently mentioned in the nursing home culture change literature. Here we show the breadth of this literature and the gaps in how these processes are studied. Then we discuss the importance of studying employees' communications of their values through two-way communication, which is often ignored when the focus is on straightforward top-down conveyance of mission and purpose.

When leaders of health provider organizations think about transforming organizations through their goals, missions, and work practices, they recognize that this level of change brings major disruptions to organizational activities and requires substantial tools for facilitating change. However, within the health services literature, few studies examine differences in and comparisons of transformational changes across organizations. An exception is Lee and Alexander's (1999) study of core and peripheral changes in the operations of US hospitals in which they compared transformational changes in ownership and service provision to more peripheral changes that included system affiliation, corporate restructuring, downsizing, or CEO succession. However, even their study did not examine differences in change processes but rather examined the consequences or outcomes for long-term performance.

Mechanisms for change have been studied within the safety culture literature, which has parallels to the culture change and resident-centered literature in its focus on transforming work practices throughout provider organizations. Elements of a safety culture include frequent communication, trust, leadership, teamwork, and training (Hughes and Lapane, 2006; Scott-Cawiezell et al., 2006). A lack of leadership commitment and open, timely, and accurate communication has been found to hinder an organization's ability to move from a culture of blame to a culture of safety (Scott-Cawiezell et al., 2006). Kane (2001) reminds us though that too often resident safety is assumed to be the “be-all and end-all of long term care” (p. 296), while there are other cultural values equally important to long-term care, including respect for individual autonomy and dignity.

Organizational change mechanisms must modify individual employees' heuristics and guide their work practices in addition to reinforcing values. Because organizational change requires shifts in individual employee's values, organizational mechanisms must include ways in which individuals both express their personal values and incorporate new organizational values into their systems of belief. Maitlis (2005) proposes the following consequences of this type of limited sense-making: “Organizational sense-making in which leaders engage in high levels of sense-giving [top-down communication that requires employees to accept managerial formulations of work practices] and stakeholders engage in low levels of sense-giving will tend to lead to a one-time action or a planned set of consistent actions (rather than an emergent series)” (p. 42).

Maitlis's study of the sense-making processes within British orchestras finds that effective management practices that engage employees in their own “sense giving” can lead to vital improvisations or limited additional effort from employees. This can affect programming, income generation, and collaborative ventures with outside groups.

We discuss here the three highlighted culture change mechanisms that are important in linking meso-organizational change to changes in the cognitive schema that employees use to structure their work practices: formal types of organizational communication, directive leadership styles, and training and development programs. These three mechanisms are highlighted because they are extensively examined within the nursing home culture change literature. We discuss their use as well as theoretical gaps in research on how these mechanisms for change affect organizational behavior using the Bartunek model as a framework.

Formal Communications

Bartunek (1984) emphasizes that organizations must become more decentralized to encourage increased participation from staff in decision making because in the process of restructuring, individuals throughout the organization must rethink interpretive schemas. Formal communication channels—central to participation in decision making and employees' understanding of their work environment and organizational goals—are therefore an important mechanism in the alignment of individual practices and organizational consensus.

Correspondingly, the nursing home literature identifies communication channels as key in facilitating culture change. Opening communication channels generates input from diverse staff and also ensures that employees maintain their focus in the organization, resulting in improvement of organizational performance (Scott-Cawiezell et al., 2005b). A flattened organizational structure has been found to facilitate fluid communication and decision-making processes for staff and management and provide greater management support for employees' goals (Chenoweth and Kilstoff, 2002). Pitkala, Niemi, and Suomivuori (2003) describe the conscious evolution of a facility that moved from a hierarchical structure to a structure based on individual and team responsibility, which ultimately improved communication and cooperation between employees and family members. Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs) in the nursing home have been found to be the most dissatisfied with existing formal communication mechanisms (Scott-Cawiezell et al., 2004) and are expected to benefit the most from increased communication and rewards for their involvement in change (Scott-Cawiezell, 2005a). Finally, the literature asserts that communication processes must be open, accurate, valid, and timely to facilitate culture change (Misiorski, 2001; Scott-Cawiezell et al., 2004 2005a).

The biggest gaps in this literature are lack of attention to the dynamics and content of interpersonal exchanges around communication of culture change and whether communication is effective in changing attitudes in addition to behaviors. It is critical, though, for employees to communicate to the managers their reasons for resisting changes in practices (Piderit, 2000) and help identify the opportunities and methods for making change successful (Dutton et al., 2001). Researchers should also look more closely at whether nonpersonal forms of communication, including newsletters or routine directives from the top leadership, are as effective as more personal contact with direct supervisors given the importance of not just immediate behavioral changes but long-term changes in attitudes.

Direct Leadership

Within Bartunek's model, leadership plays a key role in mediating how external environmental demands motivate employees' responses to organizational change. In line with traditional models of the leadership role in management (Barnard, 1938), organizational leadership for culture change includes the capacity to influence employees toward achievement of organizational goals and will either facilitate or obstruct new institutional values shaping individual employees' cognitive schemas. The nursing home culture change literature prescribes that leaders unify values across stakeholder groups and develop mechanisms that help employees align their personal values with the organizational culture.

The nursing home culture change literature includes an abundance of studies that address how leaders influence employees' values in nursing homes (Rader and Semradek, 2003; Davies et al., 2003; Deutschman, 2005; Chenoweth and Kilstoff, 2002; Scott-Cawiezell et al., 2004). At the same time, a paucity of research has empirically investigated the role of leadership in facilitating consensus across stakeholders on values in nursing homes (Gilster, 2002). A number of prescriptive articles highlight leadership's role in developing the communication of organizational values and vision and hiring staff who share these values and vision (Deutschman, 2001). Leadership also improves employee and resident satisfaction with cultural values (Dixon and Bilbrey, 2004) and supporting an environment of ethical decision making (Falek, 1986).

A critical element of direct leadership includes how the administrator organizes individuals within departments or teams. Leadership must be consistent when using team and group processes to achieve goals and effect change (Rantz et al., 2004). From data on five nursing homes, Scott-Cawiezell and colleagues (2006) found that when leaders do not communicate openly, accurately, and in a timely manner, employees became frustrated with the lack of support. Conversely, strong social ties within subgroups of employees can weaken the bond between the employee and the employing organization and challenge leadership's ability to achieve a holistic organizational culture (Helms and Stern, 2001). Nursing homes face a challenge when they develop specialty care units around the needs of residents, which has been done for dementia care, rehabilitative services, and other medically intense care, among others. In these cases, the staffing levels and mix differ considerably by unit, as do the demands from residents, and strong subcultures unique to units may hinder organizational change. For example, physicians may be more frequently present in a rehabilitative unit than in the long-stay nursing unit and, hence, may affect the organizational climate and work practices in one place but not the other.

Frequent interactions with physicians and other clinical professionals who may not understand or communicate the importance of resident-centered care may slow transformation to resident-centered care in medically intensive units. Fundamental parts of the leader's role that are not well covered in the nursing home culture change literature include mechanisms that leaders use to hold employees accountable for work practices across the organization and reward systems that minimize the effects of subunit cultures. Overall clarity on the ways in which employees and managers interrelate can be key to understanding these variations in culture change processes.

Programs for Training and Development

Training and development are common tools for both enhancing employees' experiences of and encouraging increased use of new work practices. Theoretically formal training and development programs are often conceptualized as mechanisms for transferring knowledge or skills and building employees' sense of confidence in their new knowledge, skills, and work practices (Chen and Klimoski, 2007). However, formal training and development programs should encourage and cultivate a sense of empowerment at the same time that they transfer knowledge in order to affect the practices of individual employees.

As part of empowerment, a critical aspect of training and development is that employees share their personal values and are allowed to express these values in order to facilitate transformation in their perceptions of what are high-quality and resident-centered work practices. These processes are critical to overcoming threat rigidity in personal behaviors. Threat rigidity, or resistance to giving up routines in crisis situations, has been found to lead to dysfunctional responses to change, including organizational change. Weick (1993) describes the life-threatening consequences of threat rigidity in his analysis of the Mann Gulch fire disaster, in which thirteen young men died, in part because, as Weick argues, they were unwilling to try new and potentially lifesaving routines such as building counterfires and not fleeing in front of an approaching fire. Their resistance to these strategies came from establishing different routines for fighting fires through years of training and an unwillingness to try new ideas when crisis occurred. These types of responses are all too common within organizations. Traditional training and development programs can demonstrate the utility of new methods but do not necessarily convince staff, who may resist new methods because they are resistant to change or believe that their existing routines still hold value. Part of the logic behind facilitating value-based discussion among employees is to develop among employees a greater willingness to change (Weick and Sutcliffe, 2007).

In a comparison of magnet to other nursing homes, Rondeau and Wagar (2006) found that the magnet facilities differ from other facilities in that they have progressive decision-making cultures and commit resources to staff training that then leads to higher levels of nurse and patient satisfaction. Shanley (2004) supported empowering employees by increasing their involvement in designing the objectives for training and development programs.

The nursing home culture change literature has identified training and development programs as key to empowering nursing home employees, influencing their values, and raising awareness of cultural gaps between staff and residents (Davies et al., 2003; Gould-Stuart, 1986). Trained nurses have been found to be better than untrained nurses in using verbal strategies promoting dignity, self-respect, choice, and independence among residents, illustrating how training influences employees' interpretive schemas (Davies, 1992).

However, nursing homes often do not invest sufficient resources into training and development. Ross and colleagues (2001) found that long-term care administrators value continuing education but commit few resources to it and frequently place responsibility for completing continuing education on the individual rather than making it a corporate responsibility. Correspondingly, Hughes (2005) found that nurses value continuing professional development but have little time to reflect on what they learn or to incorporate new methods into work practices after professional development. In sum, there are competing values, including efficiency, that are not raised during training but critically constrain how individuals act upon their values.

Approaches to Studying Culture Change

Research on organizational culture is divided in terms of both the methods of analyses used, which range from experientially based reflection to large surveys of structural and performance measures across facilities, and in the fundamental conceptual model, to studying culture that underlies these approaches (Martin, 2002; Scott et al., 2003b). Indeed, research methods have divided cultural researchers into two approaches: the typological and the dimensional or variable (Scott et al., 2003a). In Scott and colleagues' dichotomy, a typological approach to cultural research identifies an organization's culture as a unique combination of inseparable structural, symbolic, and behavioral elements within the context of a specific organization. In contrast, the dimensional approach defines organizational culture through common elements comparable across contexts and among which various combinations may be successful. Typological studies use case studies to describe cultures within individual organizations while dimensional studies use larger survey analyses to identify the presence of cultural elements across a range of organizations. We judge both approaches as useful and complementary.

The study of culture change recognizes that organizations share common cultural characteristics but that current instruments may not be sufficient for identifying where employee resistance may occur to transformational change. For example, culture and climate surveys frequently ask employees to provide their best judgment of “the organization's” values rather than their own (Scott-Cawiezell et al., 2005a), which means that employees are asked to minimize their own personal values in the ratings they give. Subsequently, organizational climates are measured by taking averages on cultural values rather than studying the range or variance in estimates provided (Cameron and Quinn, 1999; Scott et al., 2003b; Shortell et al., 1991). In other words, cohesion is judged or measured as the extent of agreement among employees on single measures of climate, which is an important facet of organizational operations but does not measure the extent of disagreement among employees on cultural values. More generally, variable-based measures of culture provide useful tools for studying the relationship between organizational culture and important measures of organizational performance (Shortell et al., 1991) or other organizational characteristics (Zazzali et al., 2007) but are not useful in measuring differences in individual perceptions of culture change or the extent to which these perceptions coincide with macrochanges.

We next discuss ways to assess the attitudes of frontline caregivers, organizational mechanisms for influencing change, and organizational performance in detail through in-depth qualitative studies of organizational processes. The description of culture change mechanisms offers important guidance to practitioners, who routinely develop organizational processes and can benefit from a description of how these processes work across a variety of settings. Indeed, these studies may be more valuable to the practitioner than the common quantitative statistical approach since managers have little ability to manipulate organizational change at the level of organizational structural variables.

Our review of the existing nursing home culture change literature found that it was dominated by prescriptive claims or rich descriptions of unique cases, indicating a proclivity toward descriptive work on these types of changes. Mechanistic studies take qualitative research one step further in terms of describing organizational processes specifically in order to identify key elements of organizing activity. As Davis and Marquis (2005) write, “Social mechanisms are ‘sometimes true theories’ … that provide ‘an intermediary level of analysis in-between pure description and story-telling, on the one hand, and universal social laws, on the other.’ … If a regression tells us about a relation between two variables—for instance, if you wind a watch it will keep running—mechanisms pry the back off the watch and show how” (p. 336). Hence, existing qualitative studies should be enhanced by a greater focus on the social and technical contexts within organizations that influence the process of culture change. And more extensive analysis of how individual employees respond within the context of transformational changes will improve our understanding of how mesolevel mechanisms for change can speed up adoption of practices related to new organizational values.

Evaluation of organizational transformation necessitates simultaneous investigation of the multilevel context in which transformation occurs (Kozlowski and Klein, 2000; Rousseau and House, 1994). When we use Bartunek's theoretical framework, we see that antecedents of culture change exist at multiple organizational levels, and variability within each level may hinder or facilitate progress toward organizational culture change. At the microlevel, work practices carried out by frontline caregivers may not align with managers' expectations, and conflict over work practices may arise because individuals may differ in their cognitive schema of how work should be conducted. At the mesolevel, consensus on emergent work practices may be challenged, and managers may find themselves ineffective in influencing changes. At the macrolevel, emergent work practices will affect organizational performance, and the benefits of patient-centered care may vary across institutional environments.

Current research in nursing home culture change has provided extensive examples of the mesolevel mechanisms by which health providers manage transformational changes, including the development of formal communication mechanisms, the definition of individual leadership roles, and the institution of training and development programs. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses of mesolevel mechanisms for change can be informative. With these mechanisms, providers can effectively promote emergent work practices, monitor organizational performance, and convey the benefits of patient-centered care. Consequently greater understanding of when these types of organizational mechanisms are present and how well they work for change is important. However, much of the work on ways to create organization transformations such as culture change neglect the microlevel interpersonal processes occurring during the promotion and communication of new practices; future work should include more research on the microdynamics common in transformation because it is essential to effectively change behaviors and attitudes at the individual or microlevel (Morgeson and Hofmann, 1999).

Microlevel changes in employee attitudes and behaviors must be studied using different approaches in order to understand clearly how the change process works. Employees may not fully express their attitudes in the workplace or may be reticent to mention the complement of conflicting values that they balance when accomplishing their work, making invisible the personal choices they confront daily regarding trade-offs among conflicting resident needs. Subsequently, questioning employees regarding their usual work practices or their perceptions of organizational climate will not reveal key personal differences in how they are experiencing and responding to transformational change. Furthermore, identifying expectations for how work practices should be carried out is not sufficient because frontline caregivers may not follow managers' expectations or there may be conflicts over how to conduct work practices that arise during the workday. Organizational behavior researchers have frequently used this line of inquiry by studying processes through which collectivities coalesce and organizing occurs (Davis and Marquis, 2005). This work must be focused specifically on responses to transformational change; otherwise, the extent of data to collect becomes a daunting task. Qualitative methods, including observational and interview studies, will allow researchers to elaborate how employees identify with and promote transformational values and the extent of interpersonal or intrapersonal value conflicts.

We propose a mixed-method comparative case study research design as most appropriate for the investigation of organizational transformation. Comparative case studies enable exploratory intraorganizational assessments of internal dynamics and quantitative methods enable interorganizational comparisons of performance (Ansari, Fiss, and Zajac, 2010). With information collected from in-depth case studies, the social processes that lead to certain outcomes can be inductively identified and compared across cases (Easterby-Smith, Burgoyne, and Araujo, 1999). By incorporating multilevel data from different sources to create an overall narrative of how culture change occurs, the processes through which mechanisms are effective in facilitating culture change become clear.

Identifying a purposeful sample of heterogeneous cases like nursing homes will facilitate either confirming or disconfirming conceptual insights that arise during inductive analysis of qualitative data. In order to study organizational culture change, incorporating the perspectives of multiple individuals who have a role in achieving culture change is necessary to evaluate whether there is consensus during change and whether mechanisms lead to individual-level changes in interpretive schema. In addition, the collection of data on individual perceptions of how changes are implemented and how mechanisms facilitate change is important for understanding the significance of and variability in interpretive schemas during change processes.

Qualitative data collected through observations and interviews can provide detailed information on the change process and individual responses to change. At the organizational level, conclusions about how culture change occurred and whether it was successful would be based on confirming reports from multiple employees. In other words, observation and interview data would be triangulated to identify salient processes of change within each case (Yin, 2003). The elements of culture change that should be compared in case studies of how transformation occurs include individual behaviors, interactions, and social processes that can be visibly observed during site visits, and attitudes and perceptions that are not observable but may be best assessed through personal accounts expressed in interviews. The addition of organizational-level performance data reflective of resident-centeredness creates an overall narrative about culture change within facilities. However, defining success also depends on qualitative evaluation to understand why some nursing homes succeed whereas others fail to achieve culture change.

To collect information on individuals' attitudes and perceptions of work practices, an interview guide should be developed to include questions pertaining to the perception of role and experiences with the work practices being implemented to achieve culture change. Time spent observing participants before interviews helps to develop trust between the participant and the investigator, which is important when asking potentially sensitive questions about how the participant feels about his or her work. On the basis of observation and interview data accumulated as data collection progresses, an interview guide can be developed to draw out information necessary for corroborating emerging findings.

Qualitative analysis can begin after the first observational data are collected. In this approach, we suggest researchers develop a logic that includes inductive and deductive reasoning because substantial literature already exists describing culture change processes at a basic level. Coding data and the identification of key theoretical categories are facilitated by immersion in the data. However, theoretical categories can be prespecified while also using a grounded theory approach to reveal new insight (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser, 1992; Strauss, 1987). Qualitative data should be reviewed with prior concepts in mind simultaneously with an openness to new ideas that stand out from participants' perceptions of how culture change is occurring. Consequently, the first phase of coding should entail both focused and open coding. This may involve aggregating codes for concepts that the participants routinely group together, some of which may be eventually integrated into single theoretical categories, until a codebook has been refined and finalized.

The use of qualitative data in empirical investigation is inherently subjective; however, additional coders and performing checks of reliability and validity can strengthen the objectiveness of emerging findings. Writing memos over the course of data collection, coding, and analysis to propose and clarify links within the analytical themes and theoretical categories is also recommended to develop case comparisons (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw, 1995).

Much of the traditional literature on organizational culture seeks to identify consensus on work practices and values. Organizational climate studies, for example, routinely aggregate employee survey responses and report only mean values for key cultural characteristics. However, our emphasis on the process by which change occurs requires that researchers seek out and identify when consensus does not occur and, more fundamentally, how individuals negotiate agreement over work practices. Hence, the focus should be on identifying individual differences in their interpretation of organizational activity and how groups in the workplace come to consensus when it does occur. In other words, much of the critical information would be lost in survey studies of organizational change. Researchers also are often insensitive to how process changes over time, especially as culture change occurs. At a minimum, researchers should report more about the context in which these changes occur and, ideally, collect information over time in order to understand how negotiation and conflict work out. At the same time, more macro and quantitative studies would be useful in identifying and evaluating the common practices that employees and managers use for communicating and agreeing on work practices. This requires more in-depth research on the forms of communication, leadership processes, and training and development programs used across organizations.

Conclusion

Organizational culture and culture change are well-studied concepts, although the terms may be overused in health care, where many types of organizational change are labeled or believed to be dependent on culture change. However, the loose empirical and policy use of the term culture change fits with the theoretical diversity within organization theory in how culture is variably defined and measured (Martin, 2002; Scott et al., 2003a). Unfortunately, this diversity has contributed to a literature in which authors do not always explicate the theoretical approach used and may ignore studies that use methodologically different approaches to research. The study of culture change will require a fundamental shift in our approach to studying organizational culture that first recognizes the strengths of multiple types of existing methods, including both qualitative and quantitative approaches, and that seeks to synthesize these approaches in order to develop a better understanding of the process of change and the sequence of steps by which individual employees come to accept new practices promoted by management.

One avenue of research focuses on the unique aspects of culture within particular organizations, and researchers using this approach may agree that there are common managerial practices that top management can use to influence culture and how it changes. Hence, the bridge between quantitative and qualitative work here is in agreeing on what elements of culture change are common across organizations and developing better ways to evaluate how changes in cultural norms occur. We argue that a key missing element in the literature is in exploring how organizational processes such as training programs, personal leadership practices, or the use of formal communication channels affect individual adherence to new cultural practices, as it is through the translation from organizational change to individual behavior change that implementation of a new work practice is facilitated and incorporated thoroughly into an employee's work routines. Resident- and patient-centered approaches are an ideal context in which to study this issue because implementation of these approaches requires changing multiple work practices within health care settings and are sometimes haphazardly or only partly adopted because of the complexity of these changes (Keith, 2012). As has been found in the nursing home industry, many providers may argue that they provide resident-centered care, but the approach and work practices used vary considerably from one provider to the next (Doty, Koren, and Sturla, 2008) and possibly even within a provider organization. As Everett Rogers notes in his classic work, Diffusion of Innovations (1995), the speed of implementation is a fundamental component of innovation adoption and a major element in recent approaches to improving the clinical quality of care.

The nursing home sector, maybe more so than the acute care sector, has seen public support for both resident-centered approaches and social movements urging institutionalization of this approach to caregiving. In addition to the collection of facilities that promotes specific culture change models and that we identified early in this chapter, there are networks of support for nursing staff promoting resident-centered care (e.g., see www.pioneernetwork.org). As well, initiatives at both the state and federal levels have incorporated culture change practices (Koren, 2010). In addition, as early as 1986, a resident-centered focus was identified as an important aspect of quality of nursing home care in a key Institute of Medicine report on nursing home quality (Institute of Medicine, 1986; Koren, 2010).

A critical part of making long-term care services more resident centered is the development of better integration across medical and nursing services and social and residential services. This is because individuals do not necessarily recognize their health needs as distinct from the everyday functional care needs they experience. Performance and quality of the service provider are judged through the trajectory of outcomes for individual residents. For example, the challenge of defining quality in long-term care requires a focus on sustaining quality in care over a long period of time and challenges providers to define performance indicators that take into account changing resident needs. Although our focus in this chapter has been on using the nursing home sector to illustrate how to study the process of culture change in health care organizations, the sector is also a critically understudied component of our health system and less often highlighted in the theory of health care organizations. We think that it is valuable to consider more examples from the nursing home industry and other types of long-term care providers because the challenge of integrating social, residential, and clinical care has unique traits that make application of models developed in the acute sector problematic.

At the same time, the service staff in nursing homes traditionally includes a mix of professional, semiprofessional, and low-wage positions, and nursing homes are challenged to incorporate culture change across staffing levels. Moreover, there is little time or money devoted to the continuing education of staff. Hence, providers and policymakers need to consider both how quickly changes can be implemented and the cost-effectiveness of transformational changes within these provider organizations. These issues are becoming more relevant throughout the health care system because of reimbursement changes initiated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. These actions link the financing of health care services to performance metrics relevant to a continuum of services and to chronic care outcomes. But our ability to learn from how culture change is currently implemented among nursing homes requires further research into the organizational mechanisms used to implement these dramatic changes.

Key Terms

- Culture change

- Institutional change

- Macrolevel change

- Mesolevel change

- Microlevel change

- Nursing homes

- Organizational culture

- Resident-centered care

- Transformational leadership

- Typological approach to culture research