Chapter 8

Differentiated, Integrated, and Overlooked

Hospital-Based Clusters

Patrick D. Shay, Roice D. Luke and Stephen S. Farnsworth Mick

Learning Objectives

- Define hospital-based clusters and distinguish between urban boundary and regional boundary definitions of clusters.

- Understand the history of the emergence of hospital-based clusters during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, including their empirical growth during the past two decades.

- Evaluate clusters' adoption of differentiated and integrated organizational forms.

- Examine clusters' exhibited patterns of vertical differentiation and other horizontal and vertical interorganizational arrangements

- Apply a multitheoretical perspective to explain the variation in differentiation and integration activity observed among clusters.

Take a quick look at the competitive makeup of health care organizations in any single market in the United States, and you are likely to find at least one, if not several, hospital-based health care systems that serve as the primary and dominant health care providers within their local communities. Indeed, the existence of these entities, most of which are clusters of two or more acute care hospitals and other associated health care businesses, and the prominent role they play in the US health care system may seem obvious to the casual observer. Ironically, despite their importance as delivery modalities and their potential effects on competition and policy, these distinctive organizational forms—the clusters—are strikingly understudied. The gaps in knowledge appear even at the most basic levels of analysis, including their measurement and conceptualization. What are these systems? How did they come to exist? And how does their emergence and development speak to our understanding of organizations, organizational forms, and organization theory?

This chapter first discusses the evolution of cluster configurations with multihospital systems, particularly over the past two decades just ended. Second, we demonstrate empirically the changing characteristics of these systems, with an emphasis on their geographical clustering and their configuration of hospitals. Third, we seek to frame them within theoretical concepts that are central to organization theory, specifically differentiation and integration. And, finally, we examine evidence that the clusters exhibit patterns of vertical differentiation in the distribution of clinical capabilities across cluster members.

When we say that clusters have been overlooked in the health services literature, we mean that although other hospital-based organizational forms have received considerable attention on both an empirical and theoretical basis, the concept of spatial proximity, a distinct requirement of clusters, presents new and previously underappreciated ways to understand the contemporary organization of ambulatory and acute care services. Spatial proximity is a primary trait that distinguishes clusters from other hospital-based organizational forms such as multihospital systems (MHSs). This distinction is crucial because, as we argue in this chapter, geographical distribution profoundly influences health care organization forms, arrangements, and activities. Studies that broadly examine MHSs in general fail to differentiate between MHSs entirely operating in a single local market (which also qualify as clusters) and MHSs with facilities dispersed across a regional or national level. And it merits consideration that many regionally—and nationally—based MHSs have themselves organized into collections of subsystems in separate local markets (i.e., clusters), yet studies often do not separately examine these clusters but instead lump subsystems together under their larger parent organizations.

A second trait that distinguishes clusters from the frequently examined integrated delivery systems of the 1990s or the accountable care organizations of today is the unequivocal requirement of shared, or single, ownership. As we later note, shared ownership among cluster members provides the means to navigate strategic paths that may not be feasible or sustainable under contractual or network relationships. Thus, to specifically examine clusters requires consideration of hospital-based organizational forms that are spatially proximate and share common ownership, which does not universally describe other commonly examined hospital-based forms such as integrated delivery systems, accountable care organizations, or even multihospital systems in general. We argue that a specific consideration of clusters is distinct, merited, and previously understudied, and this chapter addresses this current gap.

In addition, our examination of clusters runs contrary to the common focus on individual hospitals within the health services literature. For well over a century, the dominant point of departure in health care scholarship has been the acute care hospital and, more specifically, individual freestanding facilities (Stevens, 1999). It is reasonable for scholars to have focused on individual hospitals, if for no other reason than that these typically were the largest, most complex, and most costly provider units within a market. Even with the steady rise in MHSs in the 1970s and 1980s, individual hospitals remained a primary analytical focal point, as most MHS facilities operated relatively independently of other same-system facilities in their areas (Mullner, Byre, and Kubal, 1981; Schramm, 1981; Watt et al., 1986). However, we echo arguments made by others (see Shortell, 1999) that to maintain our focus solely on individual hospitals would be misguided because we would be disregarding the reality that most hospitals now participate in the increasingly dominant organizational form of hospital-based clusters.

Hospital-Based Clusters

This examination of clusters is set apart from studies that address hospital systems in general but without regard to system members' geographical proximities. A hospital-based cluster may be defined as a health care system that operates two or more hospitals within a specific local or regional market. We define the clusters using two specifications of cluster boundaries: urban clusters—the boundaries are limited to a urban area, with urban defined as metropolitan (METSAs) or micropolitan (MICSAs) statistical areas—and regional—the boundaries extend beyond urban limits to include same-system facilities located in nearby nonurban areas.

It is essential to take geographical proximity into consideration when examining hospital systems to acknowledge the long-recognized interdependencies that exist among geographically proximate provider organizations and distinguish the numerous subsystems that operate in local and regional markets from their larger national hospital systems (such as HCA, Tenet, and Ascension Health). All of this underscores the view that health care is a local good.

To avoid confusion, it is important to acknowledge alternative definitions of clusters. For instance, Porter (1998) defined clusters as “geographic concentrations of interconnected companies and institutions in a particular field” that “encompass an array of linked industries and other entities important to competition” (p. 78). Porter's clusters thus refer to spatial collectives, the members of which share common space and business interdependencies but not common ownership. By contrast to this conceptualization of clusters, the geographical combination of entities under shared ownership, as is the case for hospital-based clusters, introduces considerably more potential for the joined entities to engage in coordinated differentiation and integration activities.

In the health services literature, Fennell (1980 1982) and Thomas, Griffith, and Durance (1981) applied the term cluster to a collection of geographically concentrated hospitals in an urban region that provide care collectively to the residents in a local community. This is similar to the Porter concept, except that the definition is limited to one industry or, more specifically, one organizational form within the health care industry: the acute care hospital. This cluster concept does not require single ownership or system membership, only geographical proximity and informal collaboration. In contrast, our application of the cluster term refers to two or more geographically proximate facilities that belong to the same system and therefore have considerable potential to redistribute service capabilities, coordinate the provision of services, and share market strategies.

Clusters: A Brief History

Clusters as managed systems of delivery have an evolutionary history in health care. They can be traced from early–twentieth-century attempts in policy to promote collaboration among hospitals within regions (without shared ownership), to late–twentieth-century conceptualizations of clusters as loosely bound collectives or networks—so-called integrated delivery networks (IDNs)—to the current version of the clusters in which the members share common ownership (the latter are the focus of this chapter).

Public policy in the first half of the last century encouraged hospitals to engage in regionalization, which was merely another term for efforts to engage in vertical differentiation (coordination of capacity by level of care) and integration (coordination of flows of patients, services, and information) among hospitals (Lembcke, 1951; Donabedian and Axelrod, 1961; McNerney and Riedel, 1962; Pearson, 1975). A primary objective of regionalization was to reduce the duplication of resources and to coordinate care regionally, by joint planning of capacity and managing transports, consultations, and referrals (Dimick, Finlayson, and Birkmeyer, 2004). The primary limitation of this policy strategy was that it relied on incentives to get otherwise strong competitors and highly independent actors to forgo self-interested investments in capacity and relax autonomy demands in favor of benefits that would accrue to the collective of providers and to the community as a whole. Such collaboration failed to take hold, however, in part because the regional collaborative structures were too fragile for them to resist the inherent forces of dissolution.

In the early 1990s, leaders in the hospital sector—followed shortly by the affirmation of scholars in the field (Conrad and Shortell, 1996; Burns and Pauly, 2002)—advocated a self-initiated, collaborative structure that would achieve some of the objectives of regionalization: they promoted the formation of IDNs (American Hospital Association, 1990; Catholic Hospital Association, 1992; Advisory Board, 1993). These differed from the regional models of the first half of the century in that they focused more on the coordination of patient flows than the restructuring of service capacities per se. The industry assumed that the former would require limited commitment from each organization and thus that the local providers could come together under loosely coupled organizational arrangements to achieve the limited objectives of patient integration. Industry leaders also made another, arguably less reasonable, assumption that by combining a broad range of providers within regions in this way, they could respond as collectives to emerging changes in insurance contracting. This thus injected the IDNs more directly into the strategic arena, but without having to fundamentally restructure interorganizational arrangements among the collaborators.

The industry proposed this model in part as a response to continuing concerns over health care costs and quality, experimentation with regulatory and payment strategies, and a growing consensus that the sector needed major reform. Industry leaders thus recognized the need for local and regional coordination but overlooked, at least in their conceptualization of the IDN, the need to restructure interorganizational arrangements in ways that would enable them to manage the rather significant strategic demands the environment would place on them. They also assumed that by relying on contractual rather than ownership relationships, they would preserve historic professional autonomies. The latter, they hoped, would make it easier for them to induce physicians to participate in the IDNs as well.

Ultimately the IDN as a concept failed, for a number of reasons. The insurance contracting rationale for comprehensive system formation did not take hold, physicians proved far more difficult to manage in that period than had been expected, and loosely structured arrangements proved inadequate to manage what effectively were highly strategic interorganizational agendas. Nevertheless, the industry's advocacy of the IDN concept in the 1990s played an important role in unleashing change, primarily by softening reactions to local system formation and, out of this, enabling more tightly structured systems to form.

In the wake of the 1990s environmental turmoil, the hospital sector mostly abandoned network arrangements, giving primary attention to hospital acquisitions and mergers, which produced the clusters that are the focus of this chapter. Today hospital-based systems use loose coupling for mostly tactical reasons, such as to enable targeted collaboration between otherwise highly competitive local partners or as a transitional step that might ultimately lead to full acquisition. In other words, rather than enter into comprehensive and essentially ungovernable network arrangements, the hospital sector since the 1990s has aggressively built hospital-dominated, ownership-based, market-consolidating system clusters at local or regional levels, or both (Cuellar and Gertler, 2003 2005; Luke, 2010). Even the large, highly dispersed multihospital systems such as HCA and Ascension Health have engaged in cluster formation in this way, as have the far more numerous, and often more powerful, smaller, mostly nonprofit systems that have formed in and around many local markets across the country.

The hospital sector moved toward cluster formation for a number of reasons, in addition to the obvious ones of pursuing market dominance and capturing the advantages of scale. Clustering enables systems to reconfigure both administrative and clinical structures in order to improve performance and strengthen strategic positions. Clustering especially enables systems to rationalize clinical capacities (e.g., unbundling surgery into ambulatory surgery centers), create centers of excellence by differentiating hospitals that are located relatively close to one another, implement shared infrastructures for better management of service delivery, coordinate competitive service-based strategies, integrate physician and hospital agendas and strategies, and, of course, integrate care delivered to individual patients, the focus of the IDNs of the 1990s. (For a discussion of the advantages of service concentration in health care, see Porter and Teisberg, 2004, for their call for a new, redefining framework of health care competition.)

Another, and important, advantage for clusters has emerged since passage of health care reform legislation. Given their increased scale, geographical coverage, and diversity of service offerings, the clusters are well positioned to play a leadership role at the local market level in responding to policy initiatives focused on accountability, improved “systemness,” and the coordination of care delivered to populations of beneficiaries—all key structural features of accountable care organizations (ACOs) as conceived under health care reform (Fisher et al., 2007; Shortell and Casalino, 2008).

Two Decades of Change

Empirical evidence suggests that hospital-based clusters not only increased in numbers during the 1990 and 2000 decades, but also have come to dominate local health care markets. We illustrate this by comparing the numbers and positions of clusters in 2009 to patterns in 1989, a year that just precedes the turbulent changes that occurred in the 1990s.

Our assessment of clusters and hospitals in clusters is based on the 2006 American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey of Hospitals data that we subsequently updated and expanded to reflect MHS and cluster memberships as of 2009. These updated data include MHSs missing or hidden in the 2006 Annual Survey, as the AHA allows many MHSs and clusters to report as single facilities, which leads to significant underestimates of hospital participation in MHSs and their clusters. In order to compare clusters between 1989 and 2009, we applied 2006 Census Bureau designations of urban areas to both years, focusing on METSAs and MICSAs. Clusters were defined according to both urban boundaries and regional configurations of same-system hospitals. The update of 2006 data to 2009, as well as the adoption of regional in addition to urban boundaries, added nearly 20 percent more MHSs and hospitals in MHSs over what we otherwise observe using urban boundaries only.

In 1989, even after two decades of steady growth in hospitals joining MHSs, only 38 percent of all acute care hospitals (nonfederal) were affiliated with MHSs. However, twenty years later, by 2009, that number had risen considerably, with 57 percent of hospitals being members of systems. Significantly, most of this increase occurred in urban areas. Indeed, 42 percent of hospitals in urban areas were system members in 1989, which compares to 65 percent in 2009. The rise in rural areas was less dramatic, increasing from 26 percent to 44 percent during the same twenty-year period.

When we look at the systems and specifically at the clustering of system hospitals in urban markets (again, defined as MICSAs and METSAs), 48 percent of MHS hospitals located in urban areas were grouped into clusters of two or more same-market, same-system facilities in 1989. This compares to the clustering of 69 percent of MHS hospitals in urban areas in 2009. When we solely examine this activity within METSAs (excluding the smaller MICSAs) during the same period, hospitals participating in clusters increased from 56 to 79 percent between 1989 and 2009, respectively. So in this twenty-year period, not only did system membership grow rapidly, so too did combinations of those system hospitals into groups of two or more same-system facilities within the same urban areas.

In addition, the shift toward urban clusters in recent decades has greatly concentrated health care in local markets. Collective average market shares for clustered versus freestanding hospitals, controlling for market size, rose significantly from 1989 to 2009, especially within the larger markets. For instance, in 2009, clusters averaged 71 percent of aggregate shares in markets with populations exceeding 1 million, an increase of 33 percentage points from 1989.

Shifts also occurred in the sizes of the clusters, defined by the number of hospitals per cluster. Notably, in the largest markets (at least 1 million population), the number of clusters with four or more hospitals in them rose by 114 percent over the twenty-year period, whereas the number with just two or three hospitals fell by 1 percent. By contrast, in the markets with total population between 250,000 and 1 million residents, both size categories increased. In the smallest markets, only the smaller clusters (composed of two or three hospitals) can be found due to the lack of numbers in small markets.

These differences between large and small urban markets expose a flaw that arises when clusters are defined by only those hospitals located within urban boundaries. Indeed, many urban-based clusters, especially those located in smaller markets, combine with nearby rural facilities, sometimes even with hospitals that are located one hundred miles away or more. By relaxing the urban boundary and including nearby same-system facilities in nonurban areas to accommodate regional clustering, the number of clustered urban hospitals and their nonurban partners jumps considerably, especially for clusters centered in the smaller urban areas.

Use of the expanded regional cluster definition that includes nearby facilities increases the percentage of MHS urban facilities that are clustered with one or more other facilities (in the same market or nearby) in 2009 from 79 to 94 percent. And 75 percent of MHS rural facilities now are counted as members of regional clusters, which is significant, since rural hospitals, under the regional definition, represent 29 percent of all MHS hospitals counted as regional cluster members.

Our analysis defines regional clusters as combinations of two or more same-system hospitals in which the nonurban members operate within 150 miles of the largest urban MHS member. This distance accommodated many clearly regional configurations, especially many located in midwestern and western states, such as UPMC (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center), Intermountain Healthcare (in and around Salt Lake City), Mayo Health System, Sanford Health, Billings Clinic, and East Texas Medical Center Regional Healthcare System. Overall 82 percent of cluster members were within 50 miles of their cluster centers (the location of the largest urban member), 14 percent were between 50 and 100 miles, and only 4 percent were between 100 and 150 miles.

The change from an urban to a regional definition of cluster boundaries as of 2009 increases the count of clusters and the number of hospitals included in clusters quite significantly, especially so for the smaller urban markets. In markets with 250,000 or fewer residents, adoption of the regional definition of cluster boundaries increases the number of system hospitals that are in or around those markets by 177 percent, which compares to increases for the medium and larger urban markets of 59 and 20 percent, respectively. This is a simple matter of scale. System hospitals located in smaller urban markets typically have no alternative but to reach beyond the urban boundaries to find system partners, whereas clusters in the larger markets find plenty of partnership opportunities within the urban boundaries and thus combine almost exclusively with same-urban market partners.

We also note that when we shift to the regional definition, the increase in the number of clusters themselves is highest for those centered within the smaller urban markets—58 percent increase compared to 15 and 6 percent, respectively, for clusters centered in medium and large markets. Thus, it is clear that failure to count regional partners significantly underrepresents cluster formation among hospitals, especially those that have formed in and around smaller markets.

As an example, the regional definition brings into view the Central Maine Healthcare cluster, a regional system of three acute care hospitals that operates out of the Lewiston-Auburn, Maine, METSA. Central Maine HealthCare's primary facility, Central Maine Medical Center, operates within the urban boundaries, and its other two hospitals are located beyond the METSA borders. Both of the Central Maine rural facilities exist within a forty-mile radius of Central Maine Medical Center. Under a cluster definition employing urban boundaries, the Central Maine HealthCare MHS would not be recognized as a cluster.

The regional definition also introduces differences in model type. For instance, the Central Maine cluster might be called a small market size, small urban/rural cluster. A cluster in Phoenix, Arizona, Abrazo Health Care, owned by for-profit Tenet Healthcare, operates six acute care hospitals that are all strictly located within the urban boundaries of the Phoenix market, and thus it might be called a large market size, large urban/urban cluster. The CHRISTUS Spohn Health System cluster in Corpus Christi, Texas, which operates three urban and three rural hospitals, might be called a medium-size market, large urban/rural cluster, and so on. And of course there are many cluster configuration characteristics (size of lead hospital, spatial dispersion, addition of nonhospital businesses) that could be used to distinguish among the clusters. This illustrates the value of the regional definition for clusters, as it more accurately and realistically reflects actual cluster forms.

To conclude, it is evident that from 1989 to 2009, the ownership status of the majority of hospitals in the United States changed from independent, freestanding facilities to become members of multihospital systems. And the considerable growth in system membership produced significant cluster formation at local and regional levels. Also, these clusters have grown in size and levels of market dominance and thereby have dramatically restructured the landscape of health care delivery in this country.

Cluster Integration and Differentiation

Having introduced the concept of clusters and empirically demonstrated their rise in numbers and size, we next explore the clusters as organizational forms, with a focus on the distribution and coordination across cluster members of their clinical capabilities. First, we discuss the role spatial proximities likely play in shaping patterns of service distribution across clustered hospitals. Second, we identify conditions that might need to be present for service restructuring to qualify as vertical. Finally, we examine service differentiation empirically within the clusters in search of evidence of vertical interorganizational arrangements.

Spatial Proximity and Service Capacities

The distinguishing feature of the clusters as organizations is they combine multiple, potentially interdependent hospitals in geographical proximity to one another. Unfortunately, the organization theory literature provides little guidance on how to incorporate geography into our conceptualizations of complex organizational forms such as hospital-based clusters (Kono et al., 1998). It is interesting that Pfeffer (2003) acknowledged this shortcoming, but then went on to marginalize its significance, reasoning that “space probably matters more or less depending on the time period, as communication technologies and even norms about economic and social relations at a distance have changed” (p. xx).

But geography does matter for the clusters and likely will well into the future, even as technologies change, as they are and surely will, in ways that increasingly enable consultations and procedures to be provided to patients from great distances. This is because hospitals, more specifically acute care general hospitals, treat not only complex and seriously ill patients but often patients who need care urgently. Urgency and acuity together make location an important determinant of organizational form in the hospital sector. They are also factors that clusters must consider when deciding how services might be restructured locally and regionally in the pursuit of improved organizational performance and increased market power.

It is significant that hospitals admit about 50 percent of their patients through their emergency rooms. Thus, time and travel costs are exceedingly important for these patients; accordingly, spatial proximity to patient populations becomes a priority in locating not just hospitals but specific services, depending on how important time might be in their delivery. It is also significant that for the remaining roughly 50 percent of acute care admissions, time and travel are relatively less important in determining the place or the timing of admission. These patients, which include mostly the so-called referral cases, select hospitals and pick dates for admission based on a number of factors, in addition to geographic proximity—for example, personal and physician preferences, hospital reputations and capabilities, and payment contracting arrangements between hospitals and payers. It is this second group of patients, the less urgent, schedulable admissions, that creates opportunities for clusters to consider engaging in the consolidation of hospital services—again, because for those patients, geography is much less central to the admission choices.

Differentiation and Integration within Clusters

Over forty years ago, Lawrence and Lorsch (1967) argued that complex, multiunit organizations address contingencies in their environments by restructuring their organizational subunits in ways that improve overall system performance. More specifically, they suggested that organizations do this by seeking to balance two organizational strategies: differentiation—segmentation and concentration of capacity and functionality—and integration—coordination of those differentiated units. Differentiation makes it possible for organizations to capture the advantages of scale and scope, and integration is the ability to synchronize activities in order for complex organizations to achieve a unity of effort across their subunits.

Given the continuing changes in their environments, the hospital-based clusters may find it even more important than do other organizational types to address both differentiation and integration as they seek ways to manage their highly complex and costly local and regional systems of delivery. Since the clusters for the most part came into being through mergers and acquisitions, as opposed to new construction, they combine facilities that heretofore had determined their clinical capacities independently, based on previous organizational arrangements, physician involvement, market forces, and environmental exigencies. The clusters thus might have greater need than most other organizations to rationalize their service capabilities by pursuing differentiation and integration strategies.

The form that clinical service restructuring might take will likely depend on the characteristics of hospitals at the point that they formed into clusters. Some clusters came into being with significant preexisting differences in capacity among cluster members; others joined comparatively similar hospitals that offered relatively equivalent service capabilities and might even have been very close competitors with one another. The former includes a fairly large number of clusters that typically joined a large central city referral center, which offered highly specialized services along with a full range of more general services, with a number of medium-sized suburban and smaller, less complex rural hospitals. An example is the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), which operates a large number of hospitals and other businesses, all of which surround and interact with UPMC's flagship, Presbyterian Hospital. Given the high level of service differentiation at the point that they formed, such clusters will likely reinforce existing differences over time, thus facilitating more hierarchical patterns of service differentiation.

At the other end of the spectrum are clusters that lacked significant differentiation among cluster members when they formed. These include, for example, regional clusters comprising small, rural facilities, such as those that LifePoint (a for-profit company that specializes in rural hospital ownership and management) operates in a number of regions and states. They would also include combinations of undifferentiated hospitals that operate in large urban markets. Kaiser Permanente hospitals are an example. Although there is clearly some planned differentiation among Kaiser facilities within the Los Angeles, San Francisco, and other metropolitan and rural areas in California, Kaiser tends to emphasize geographical positioning over product differentiation in an effort to serve the needs of beneficiaries who are distributed widely over a large geographical space. In most clusters, it is reasonable to expect that preexisting competencies and structures in the future will likely play key roles in shaping how individual clusters engage in service capacity differentiation and, to the extent that it occurs, integration (Coddington, Palmquist, and Trollinger, 1985; Conrad and Dowling, 1990; Burns and Pauly, 2002).

This introduces two important but very different forms of differentiation in service capacity that are likely to emerge within the clusters, depending, again, on many factors, including the capabilities each hospital brought to the systems when they formed. The first is differentiation by level and complexity of service, a form of hierarchical differentiation in which the site for patient admission or transfer would depend in part on patient acuity and urgency. This form might more closely fit clusters of hospitals that had very different levels of capability when they began. The second is differentiation by type of care, in which clusters might designate individual hospitals to become, in effect, centers of excellence in the treatment of given categories of illness—service lines (e.g., cardiology, oncology, or orthopedics) or clinical conditions (e.g., diabetes, alcoholism, or mental illness)—regardless of acuity or urgency.

These two patterns of differentiation are not necessarily exclusive or limited to preexisting service configurations. All system types can be expected to engage in either or both types of service differentiation, a point that anecdotal evidence of ongoing system change suggests may be true. Furthermore, both types are also likely to be prevalent across all major ownership types in the hospital sector (for profit, Catholic, and nonprofit non-Catholic). That said, it is the very large group of nonprofit (non-Catholic) systems, many of which formed out of the initiative of large, urban-centered, referral hospitals, that will likely take the lead in building systems based on differentiation by level of service complexity and acuity.

Vertical versus Horizontal Differentiation and Integration

Overall, since the clusters are mostly the product of hospital consolidations, they can be assumed to be horizontal organizational forms—the combination or expansion of business units that sell similar products in different markets (Fox, 1989; Conrad and Dowling, 1990; Conrad and Shortell, 1996; Snail and Robinson, 1998; Friedman and Goes, 2001; Burns and Pauly, 2002; Bazzoli et al., 2004a). However, given the potential for significant service differentiation, it is possible that the clusters could evolve into vertical organizational forms if within-cluster hospital differentiation produces a need for patients, services, or information to flow between facilities in order to care for individual episodes of illness.

It is also possible that vertical relationships could evolve, regardless of the differentiation pattern. The possibility of interorganizational exchange, however, might be greatest in clusters that differentiate more by level of complexity and acuity. In this case, lower-level hospitals might need to coordinate care given to individual patients with cluster members that offer higher levels of service. This has been a common basis for interhospital transports for decades, mostly involving transfers of patients (and exchanging consultations and clinical information) between smaller outlying hospitals to larger, urban-based referral centers. The formation of the clusters and a trend toward further service differentiation based on level of care could thus increase the volume of flows between cluster members.

But flows might also occur between cluster members differentiated by type of service. Schedulable patients would likely be admitted to facilities that offer the particular services they need. But emergency patients who are commonly admitted to the nearest hospital might, once their conditions are defined and situations stabilized, need to be transferred to other cluster facilities for care (or to noncluster hospitals, depending on proximity considerations and cluster competencies). Each form of differentiation, while distinct in logic for restructuring, might produce added interorganizational exchange and therefore the need for integrative mechanisms to be established within clusters.

As an aside, we would note that the hospital industry's 1990s concept of IDNs implicitly assumed that vertical flows would occur among collaborating providers. Initial conceptualizations of the IDN instead focused more on flows between hospitals and other types of providers than among hospitals.

We do not know how extensively vertical flows might be or how technology might minimize patient transport between hospitals. And we do not know the degree of cluster differentiation in service capacities between cluster members or which form of differentiation they take or how such forms might be combined. Finally, we do not yet know which cluster types might engage more in one form of differentiation, if at all, versus another. This is an important area for further research, especially since the clusters have become the dominant organizational form in the local and regional markets across the country.

Evidence of Vertical Differentiationvertical differentiation

We have suggested that some forms of service differentiation within clusters may appear to be vertical, especially differentiation that is by level of care. However, differentiation alone may provide an insufficient basis on which to classify the clusters as vertical models. This is because of the role that triaging or the channeling of cases (through physician referrals, ambulance protocols, hospital admission protocols, and patient education) plays in distributing cases to hospitals before admission. It is possible, of course, that if service differentiation increases over time, interorganizational exchanges could increase along with the need to implement more formally structured integrative mechanisms within the clusters.

Nevertheless, data are lacking for measuring the presence of integrative mechanisms, although we are able to measure interorganizational transports, which provide a direct indication of vertical flows between hospitals. Unfortunately, available transport data do not designate the sender hospital. Thus, such transports could (and probably do) come from other hospitals, not just same system members.

Nevertheless, we are able to examine patterns of service differentiation within the clusters, at least indirectly. We do this by comparing lead hospitals to nonlead hospitals within the clusters, with lead hospitals defined as the largest hospital in a cluster. We assume that the largest hospital is the cluster member that provides the highest order of service complexity for a given cluster. So we can compare percentages of admission and case mix measures for lead versus nonlead cluster hospitals. To the extent that the differences are as would be expected, this would indicate that the clusters are differentiated by level of care.

In the next section, we examine evidence of the following: (1) an association between service differentiation and the presence of large lead hospitals within clusters; (2) differences between lead and nonlead hospitals with respect to their case mix measures and percentages of admission (we calculate these for the hospitals overall as well as by referral and emergency admissions, which are known to exhibit very different admission patterns); and (3) for interhospital transports, differences between lead and nonlead hospitals in their respective case mix measures and percentages of admissions.

Service Differentiation

A few studies have examined the distributions of service capacity across system hospitals (Bazzoli et al., 2001; Trinh, Begun, and Luke, 2008 2010, 2014; Ozcan and Luke, 2011). The most prominent of these, the Bazzoli and colleagues (1999 2001; Dubbs et al., 2004) taxonomic study of MHSs, focused on patterns of organizational structuring. It is interesting that although this study sought to classify MHSs by level of organizational centralization, it did so in a way that makes it possible for us to use this study to examine service concentration at the cluster level. First, the study used patterns of local hospital sharing of services among clustered system members as proxies to derive their taxonomic categories. This means that their taxonomy directly reflects patterns of differentiation that are the focus of this chapter.

Second, the AHA, in its annual survey report, updates the taxonomic assignments for most of the MHSs in the country using Bazzoli and colleagues' methodology. This means that we are able to match up our 2009 measurement of MHS clusters and hospitals with the taxonomic designations assigned to each MHS (that operated one or more clusters), as reported in 2009. It also means that we are able to examine the correlations between Bazzoli and colleagues' taxonomy of MHS service concentration with the average sizes of both the lead and nonlead hospitals within the MHS clusters. If the most centralized systems (the MHSs that concentrate services the most at the cluster level) tend to have the largest lead cluster hospitals, then we can conclude that Bazzoli and colleagues' taxonomy essentially captures the level of service concentration among MHS clusters.

Using sophisticated statistical techniques, the Bazzoli study team produced five model types, based on levels of organizational centralization (their tendency to concentrate clinical services locally). The highest to the lowest in levels of service concentration (based on our interpretations of each taxonomic category) are the centralized physician/health insurance model (40 clusters with 178 hospitals), the system model (61 clusters with 265 hospitals), the centralized health system model (161 clusters with 678 hospitals), the moderately centralized health system model (182 clusters with 788 hospitals), and the decentralized health system (51 clusters with 148 hospitals).

The majority of MHSs fall into the medium range of centralization (which, again, Bazzoli and colleagues measured using service concentration at the cluster level). Of particular interest is the spread in average lead cluster hospital sizes from the most centralized systems to the least. Large lead hospitals are likely to be referral centers. Thus, by examining them, we are able to assess patterns of service concentration with the MHS clusters. Put another way, an association between degree of centralization (service concentration) would confirm that the taxonomy captures differentiation by level of services. The data are consistent with expectations. As the categories move from centralized to decentralized, the average size of the lead cluster hospitals falls; for example, the most centralized have an average size of 504 beds, whereas the least centralized have an average size of 301 beds. In all instances within each category of centralized-decentralized clusters, the nonlead average size of hospitals is less than the size of the average lead hospital. Also, interestingly, the nonlead hospitals differ little from high to low centralized systems, ranging between 109 and 162 beds. Taken together, these findings reinforce the conclusion that Bazzoli and colleagues' taxonomy of MHS organizational centralization captures patterns of service capacity concentration at the MHS cluster level. More specifically, it suggests that the taxonomy captures service concentration by level of service complexity or acuity.

Case Differentiation

Few studies have examined differences across cluster hospitals in the complexity of cases admitted to them (Luke, Luke, and Muller, 2011; Muller, 2010). In their study of seven procedure categories that the Leapfrog Group in the middle of the first decade of the century had designated as high-risk, high-complexity case types, Luke and colleagues (2011) compared lead to nonlead cluster hospitals, focusing on their roles within the clusters in providing these services. The Leapfrog Group at that time urged hospitals either to increase the volume of such procedures that they performed each year or begin to reduce admissions of patients in these categories. It is notable that the Leapfrog Group did not consider how they might change the volumes of admissions by working specifically with the clusters, which, because of shared ownership of hospitals locally, would presumably have the capacity to incorporate restructuring into the system strategies. Rather, they implicitly assumed that individual hospitals, operating on their own initiative, would find ways by which to capture larger shares of these case types or withdraw from providing such services, both unlikely prospects in the highly competitive hospital markets.

The Leapfrog Group had based its policy of service concentration on an assumption, grounded in the empirical literature, that quality was directly associated with volumes of cases that hospitals (and physicians and surgical teams) treated each year (Birkmeyer et al., 2002 2003; Halm, Lee, and Chassin, 2002; Birkmeyer et al., 2003; Sheikh, 2003; Birkmeyer and Dimick, 2004; Khuri and Henderson, 2005).

Using discharge data for the year 2009 for six states—Florida, Maryland, Nevada, Texas, Virginia, and Washington—Luke and colleagues (2011) compared the distributions of cases across cluster members for the seven high-risk procedure categories. They found that lead hospitals treated significantly higher percentages of high-risk patients by comparison to nonlead hospitals. They also found that these percentages tended to increase over time for the lead hospitals, giving them greater shares of such cases relative to those admitted to other cluster member hospitals. Both of these findings are consistent with the assumption that many clusters tend to be vertically differentiated by level of service offering across their member hospitals.

It would be important also to look beyond a small group of procedures, such as Luke and colleagues (2011) examined, to see if clusters distribute cases generally in ways that would confirm patterns of vertical case differentiation. Specifically, we examined three indicators of case differentiation, comparing lead to nonlead hospitals. We did this by examining the following indicators of case differentiation: (1) overall case mix complexity and case mix differences for referral versus emergency admission as well as the corresponding percentages of cases admitted and (2) case mix and percentages admitted specifically for interhospital transfers. Evidence that lead hospitals, compared to nonlead facilities, had higher case mixes (overall, referral, and emergency), higher percentages of referral admissions and lower percentages for emergency admissions, and—for interhospital transfers—admitted more complex cases and greater percentages of such cases would support a conclusion that the clusters tended to engage in service differentiation by level of service complexity and acuity.

We examined acute care hospital discharge data for 2009, using information obtained for the same six states that Luke and colleagues (2011) examined in their Leapfrog high-risk study. We based the case mix measure on the all diagnosis-related groups, designed specifically for assessing patients of all ages and diagnoses. A score of 1 indicates average acuity; any score above 1 indicates above-average acuity, below 1 indicating below-average acuity.

The admission percentages and average case mix indexes for all acute care general hospitals in the data set (we included all hospitals, cluster and noncluster) are as follows: emergency, 52.0 percent of admissions with a case mix index of 1.31; referral, 34.0 percent, case mix index of 1.36; other transport, 4.1 percent, case mix index of 0.78; hospital transport, 2.7 percent, case mix index of 2.24; and all other, 7.3 percent, case mix index of 0.53. As would be expected, emergency and referral admissions represent the bulk of admissions to the acute care hospitals in the six states; together they represent 86 percent. Only 2.7 percent of patients were admitted by interhospital transports, which suggests that vertical flows among hospitals, at least flows of patients, is currently minimal, although these patients were very high in their acuity and complexity. Also since such exchanges can and do come from noncluster hospitals, these numbers do not necessarily reflect intracluster transports as such. Nevertheless, we can compare percentages and case complexity for transport admissions for lead versus nonlead facilities.

We then compared lead to nonlead hospitals on case mix and percentages of cases overall and by primary source of admission (referral versus emergency). Looking at all cases admitted to cluster hospitals, we found that lead hospitals admit significantly more complex cases on average (1.36) by comparison to nonlead facilities (1.12). This is consistent with the expectation that many clusters distribute cases consistent with within-cluster vertical differentiation. Also, such differences carry over to the two primary sources of admission: referral (lead hospitals, 1.48 case mix with 36.9 percent of admissions versus nonlead hospitals, 1.21 case mix with 32.0 percent of admissions) and emergency (lead hospitals, 1.38 case mix with 49.7 percent of admissions versus nonlead hospitals, 1.17 case mix with 57.2 percent of admissions). Interestingly, the case mix averages are somewhat higher and the differences between lead and nonlead facilities somewhat greater for referral versus Emergency Department admissions. This too is consistent with the assumption of vertical differentiation (i.e., differentiation by level of care) given that the site for admission of referral patients is more subject to patient choice and physician preference than is the case for emergency admissions.

Finally, we examined patterns of interhospital transport. The case mix indexes for interhospital transport are high for both lead (2.09) and nonlead hospitals (1.77). The lead hospitals also receive about twice the transport admissions (3.3 percent versus 1.3 percent) from other hospitals (not necessarily other cluster hospitals). Also, lead facilities admit significantly larger percentages of their patients by interhospital transport than do nonlead hospitals. By contrast, differences in the percentages for nonhospital transports are not significant, which again suggests that this source of admission is much less related to differentiation in the stage or overall level of service capability.

These findings suggest that interhospital transport could become a leading indicator of interorganizational exchange within the clusters, especially if within-cluster restructuring of clinical service capacities continues to increase. This could be true whether restructuring emphasizes differentiation by level of care or type of care. Both could generate a need for coordination across hospitals in the provision of services for some patients. An increase in interhospital transports would also provide strong evidence that more attention may need to be given to evaluating service integration.

Explaining Cluster Forms Using a Multitheoretical Perspective

The next question is how we explain variation in differentiation and integration activity that exists across markets, across clusters, and even within clusters. Organization theory provides the foundation from which explanations of organizations' structures and behaviors may be developed and applied to specific types of organizations and organizational challenges (Greenwood and Miller, 2010).

As previously noted, this chapter's consideration of differentiation and integration is developed from the arguments initially presented by Lawrence and Lorsch (1967) in their seminal work within the structural contingency theory library. However, although structural contingency theory speaks to ways in which we can describe organizational activity observed among hospital-based clusters, it leaves us with only a partial explanation as to why we might observe varied forms of differentiation and integration across different organizations and markets. Van de Ven and colleagues (2012) address contingency theory, in that it assumes differentiation and integration forms are adopted solely as the result of managers' strategic, purposeful, and rational decisions. Such a perspective ignores the reality that although organizations' designs may stem from deliberate choices, differentiation and integration forms may also result from “emergent actions” based on competing stakeholder interests as well as “multiple and often conflicting environmental demands, structural arrangements, and performance criteria” (Van de Ven et al., 2012, p. 1056).

Greenwood and Miller (2010) are also critical of structural contingency theory, suggesting that its strict focus on the structure aspect of organizational design fails to adequately address the modern realities of sociopolitical tensions connected to organizations' structures and behaviors or prioritize axes of design (e.g., organizational functions, service lines, geography, and markets) that maximize competitive advantage. Furthermore, they argue that the generality of structural contingency theory—that is, its wide application across all organization types—becomes problematic when attempting to address the complexities and designs that are unique to a specific type of organization, such as hospital-based clusters. They conclude that on its own, structural contingency theory “is helpful but insufficient” (p. 84). For that matter, they contend that the same is true of other organization theories and that the limited explanatory power of each theory begs for “the application and use of multiple relevant theories” to better understand organizations (p. 86).

In other words, no single organization theory can fully explain the complex behaviors of organizations, but when they are combined with other relevant theories to form a multitheoretical perspective, we may gain a more complete picture of organizations. Such thinking is not new; other scholars have previously cited the limitations of individual theories and called for work that synthesizes and applies multiple perspectives (e.g., Luke and Walston, 2003; Azevedo, 2002; Stiles et al., 2001; Shortell, 1999). At the same time, critics of this argument (see McKinley and Mone, 2003) suggest that the various perspectives within organization theory are incommensurable and therefore ill suited for conceptual synthesis. We side with the view that the various perspectives, though certainly developed from different directions and logics, can indeed be compared and linked in both complementary and contrasting manners. We also believe that hospital-based clusters serve as a case in point as to why it is valuable and necessary to pursue work that synthesizes organization theory and applies multitheoretical perspectives.

But having begun with the concepts of differentiation and integration to describe cluster forms, where do we turn? Beyond structural contingency theory, several other organization theories directly speak to organizations' motivations to pursue strategies such as integration. In an effort to illustrate how a multitheoretical perspective may be applied to explain cluster forms, we consider our own previous work addressing integration activity across health care organizations.

First, Mick (1990) proposed a synthesis of transaction cost economics and strategic management theory to explain vertical integration and deintegration activity across the health care industry during the 1980s. Noting that both perspectives hold a narrow view of the environment, Mick's synthesized model incorporates environmental forces and market actors that simultaneously influence organizations and create “variously relevant microenvironments” (p. 225) that each organization encounters. These microenvironments may be described according to their uncertainty, munificence, complexity, and dynamism, and the varied presence of these dimensions within an organization's microenvironment affects five factors in an organization's decision to integrate or deintegrate: production costs, transaction costs, market power, corporate strategy needs, and stage of industry evolution. A key contribution of Mick's model is its acknowledgment and accommodation of diverse and simultaneous integration and deintegration within an organization and environment, determined by an array of forces.

Next, Luke and Walston (2003) sought to explain the strategic consolidation of hospitals into local systems during the 1990s by incorporating industrial organization economics, transaction cost economics, resource dependence theory, and institutional theory into a multitheoretical model. Their legitimized-strategy model contrasts health care organizations' rational motivations to pursue vertical and horizontal strategies—expanding market power, managing efficiencies, and controlling resources—with the barriers of institutional influences. Thus, in the face of market or environmental threats, strategies that are deemed legitimate may be adopted, but organizational actions that are not granted legitimacy are not permitted, regardless of any rational justification. Luke and Walston's model contributes to our ability to explain organizations' structures and activities by suggesting that “sound economic and organizational logic” (p. 292) does not always apply.

Finally, Shay and Mick (2013) address the causal factors of integrative behavior by contrasting predictions from transaction cost economics and social network theory. They view integration between acute and postacute care providers as a likely response to health care reform due to heightened uncertainty and asset specificity. However, they also propose that health care organizations displaying heightened network embeddedness may resist motivations to integrate as concerns about opportunistic behavior or competitiveness are remedied by the trust and resources gained in strong network relationships.

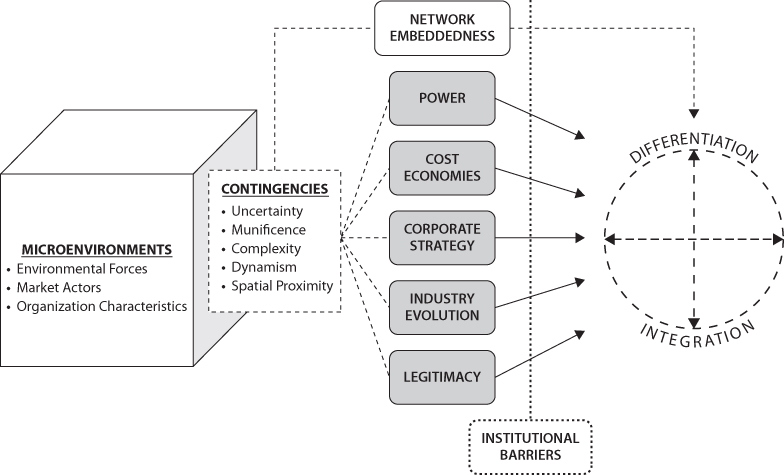

These three studies, considered collectively, illustrate how a multitheoretical perspective more thoroughly accounts for organizations' varied motivations to adopt diverse horizontal and vertical forms. We borrowed from each of these studies to create figure 8.1, a representation of an explanatory model that incorporates multiple organization theories in an effort to explain clusters' varied organizational forms. Though this model is just a surface-level depiction that, for the purposes of this chapter, does not go into detail regarding each contributing theory's constructs and propositions, it may serve as an example or template for future studies that would seek to conceptually develop and empirically test their own multitheoretical models in a more comprehensive and methodical manner.

Figure 8.1 A Multitheoretical Model of Differentiation and Integration

Our multitheoretical model begins in the same manner as Mick's (1990) synthesized model, with a depiction of local or regional clusters' microenvironments that are the product of environmental forces (e.g., reimbursement systems, population epidemiology, population demography, employers, and regulators) and market actors (e.g., competitors, providers, payers, professionals, and suppliers). We also factor in organizational characteristics that are unique for each cluster, for example, organizational units, organizational size, and organizational history. Together these factors—environmental forces, market actors, and organizational characteristics—play a role in shaping the contingencies that confront and influence clusters' strategic activities. Such contingencies include those that Mick (1990) noted—uncertainty, munificence, complexity, and dynamism—as well as spatial proximity, which we include to account for the limitations and opportunities that arise due to proximities between organizational units and organizational competitors as well as local geographical characteristics. To students of organization theory, these contingencies should sound familiar: many of the perspectives in the organization theory canon speak to the importance and impact of constructs such as uncertainty and munificence, and as we have argued, geography must serve as a key consideration as well.

Next, we incorporate and synthesize the intermediate factors that Mick (1990) and Luke and Walston (2003) portrayed would motivate differentiation and integration among clusters; each of these factors maintains connections to specific organization theories:

- The pursuit of power, including control of resources (as described by resource dependence theory), the management of threats to power (as described by industrial organization economics), and enhancing bargaining power (as described by strategic management theory)

- The effort to economize costs, including production costs (as noted in Mick's model), and transaction costs (as described by transaction cost economics)

- The pursuit of corporate strategies (as described by strategic management theory and industrial organization economics)

- Adherence to the stage of industry evolution (as described by population ecology)

- The maintenance of legitimacy (as described by institutional theory)

Each of these factors has played an important role in the emergence of clusters in markets across the United States, as we have noted throughout this chapter. And as each of these factors varies for each cluster and its members, clusters also adopt a variety of differentiation and integration forms.

However, Luke and Walston (2003) recognize that despite the strategic direction that the previously described factors may dictate for an organization, institutional norms may serve as barriers that render such strategies undesirable. We incorporate this critical point in our multitheoretical model. We also recognize the impact of network embeddedness (as described by social network theory), which Shay and Mick (2013) suggest offers an alternative means for organizations to achieve strategic objectives and address organizational challenges that would otherwise be satisfied through integration. For organizations highly embedded in network relationships, certain differentiation and integration solutions may not be required, though changes to an organization's microenvironment at any given time may also render network relationships as problematic and swing the organization back toward consideration of differentiated and integrated forms.

The result of this model is that for the reasons depicted, we see varied forms and degrees of differentiation and integration, both horizontal and vertical, which can occur at multiple levels and in simultaneous fashion for hospital-based clusters. But is it important that clusters can simultaneously exhibit differentiation and integration, or integration and deintegration, or even differentiation, integration, and network relationships outside organizational boundaries? We believe so. As Tushman, Lakhani, and Lifshitz-Assaf (2012) maintain, organization researchers must “embrace the notion of complex organizational boundaries” because “the simultaneous pursuit of multiple types of organizational boundaries results in organizations that can attend to complex, often internally inconsistent, innovation logics and their structural and process requirements” (pp. 24–25). Clusters are organizations such as these, and just as they have emerged as dominant forms that demand our attention in health care organization studies, they also serve as fertile ground for researchers to pursue and apply the synthesis of multiple theoretical perspectives.

Conclusion

What can be said about the organizational models that best characterize the clusters? Since hospitals for the most part have built the clusters and are the predominant provider entities within them, they represent horizontally configured systems. Yet many clusters, especially those that have large referral hospitals at their centers, are not only horizontally differentiated but are likely to reinforce differentiation across their cluster members. Our own data suggest that although clusters may be horizontally configured, they also operate as vertically differentiated models. Vertical differentiation in the clusters is clear, based on analyses of both structural and functional indicators. This is especially true for clusters that have large lead hospitals at their centers. The results also suggest that the vast majority of admissions, those emanating from referral and hospital emergency departments, are determined by triaging as opposed to interorganizational flows. The exceptions are hospital and nonhospital transports that by definition indicate interorganizational exchanges. To the degree that these involve within-cluster exchanges, the interhospital transports would generally be consistent with vertical exchange. While interhospital transports represent small percentages of admissions for hospitals, they do involve some of the most complex case types and thus are likely more consequential than their percentages might suggest.

It is entirely possible that if clusters do evolve toward greater vertical differentiation, they will as well engage in more interorganizational exchanges through increased interorganizational transport, increased referral and consultation arrangements, and other forms of clinical exchange. And it follows that they will become more vertically integrated over time. Thus, it is likely that the clusters will become compound structures, that is, they will evolve many, complicated interdependencies, some of them structured, others more informal, even transitory. And these interdependencies will show combinations of vertical and horizontal differentiation and, to a lesser extent, vertical integration.

It is possible, in other words, that the “integrated” part of the hospital associations and academic community's 1990s vision of IDNs might begin to take hold, at least to some extent. It is reasonable to expect that the clusters will mostly remain hospital centered given the costliness, complexity, and centrality of these entities to local health care delivery systems. However, they can be expected to continue reaching beyond the acute care sector to incorporate related sectors into their business models. While it might not be necessary for them to own all of these businesses, ownership arrangements will likely remain the central vehicle for the continued building of the clusters for many decades into the future. Also, with time, the geographical reach of the clusters is likely to expand, with many major regional combinations forming that even combine across major metropolitan areas. Put another way, the clusters have clearly replaced freestanding hospitals as the central, most prominent organizational unit of health care delivery in this century, and their position of strength and dominance will continue to grow, at least for the foreseeable future.

Future research and policy need to address these important organizational forms more explicitly and fully. We need better databases, better measurement, and better conceptualizations of the clusters. With all of the consolidation that has occurred, it would be a serious oversight were we to continue focusing almost exclusively on individual hospitals and interhospital competition, as if the clusters were relatively inconsequential players in the markets across the country. They are here, they are growing, they are becoming increasingly powerful, they have enormous potential to change delivery, and it is more and more likely that they will play a key role in shaping health care delivery in the years to come.

Key Terms

- Cluster boundaries

- Differentiation

- Geographical proximity

- Horizontal organizational forms

- Integrated delivery networks

- Integration

- Interorganizational exchange

- Lead hospitals

- Multihospital systems

- Multitheoretical perspective

- Regional clusters

- Urban clusters

- Vertical differentiation

- Vertical organizational forms