CHAPTER 10

MANAGING INTEGRATED MARKETING COMMUNICATION AND RELATIONSHIP COMMUNICATION

“Everything communicates something about a firm and its offerings – regardless of whether the marketer takes this into account and acts upon it or not.”

INTRODUCTION

This chapter addresses the issue of marketing communication and demonstrates the need for a total communication or integrated marketing communications approach where communication messages from a number of different sources are integrated. The communication circle concept is described, and the impact of various time horizons on the effects of marketing communication campaigns is analysed. Some guidelines for managing marketing communications in service are also presented. In the final sections of the chapter we discuss the relationship dialogue concept and how total integrated marketing communication and relationship marketing relate to each other. A relationship communication model is presented, where communication messages sent by a firm are considered facilitators of the customers’ creation of meaning out of these messages. After having read the chapter the reader should understand the importance of taking a holistic approach to marketing communication and know how to integrate communication activities of different natures; planned, as well as product and service, and unplanned, messages. The reader should also understand how marketing communication has an impact on several target groups and on several levels along a time span. Finally, the reader should realize the importance of the customer as a creator of meaning out of communication messages in his temporal and situational context.

MARKETING COMMUNICATION: A TOTAL COMMUNICATIONS ISSUE

Marketing communication is a substantial part of the marketing process. Conventional marketing includes market communication activities such as sales, advertising, sales promotion and communication over the Internet. However, communication is also an integral part of the interactive marketing process and relationship marketing. What employees say, how they say it, how they behave, how service outlets, machines and other physical resources look, and how they function all communicate something to the customers. The communication effect may be positive, such as ‘they really care for me here’, ‘they have modern and efficient equipment’, ‘this website is easy to use and provides useful interactions with the firm’ or ‘the employees are nicely dressed’. It may also, of course, be less favourable, such as ‘how rude their people are’, ‘what a sloppy office they have’, ‘how can it always take so long to get things done here’ or ‘why do they not keep me informed about the developments?’

There is an important difference between the communication of the traditional marketing function and that involved in the interactive marketing process. The latter type of communication is related to reality as customers perceive it. They communicate what really is as far as consumers are concerned. The relationship marketing model in Chapter 9 shows communication effects of activities in the interaction process. The former type of communication, such as advertising, is always on an abstract level for customers. It relates to the planned communication process of this relationship marketing model. Planned communication involves information that may or may not be true; however, as far as the customer or potential customer is concerned, the validity of this must still be tested. Hence, this communication is a promise about what hopefully will happen in the future. Testing takes place when the customer meets reality. There is an obvious connection here with how service quality is perceived. Marketing communication efforts like advertising and sales predominantly impact the expected service, whereas the communication effects of the interactive marketing process influence the experienced service.

For example, a retailing chain that advertises a certain product at a special price communicates a positive promise of good value. If the product is not available in the shop, or if it has already sold out, a negative communication message is created: ‘They do not advertise honestly’ or ‘They just want me to come to the shop to buy stuff. They probably only had a limited number of the advertised low-price products in stock in the first place.’ The negative communication impact of the latter is much more forceful, because it is caused by the actual performance of the retailer. Moreover, it changes the favourable effect of the first type of communication into an unfavourable image of the retailing chain.

The size of the gap between expectations and experiences determines the quality perception, as discussed earlier. Hence, here there is a truly total communication impact;1 almost everything the organization says about itself and its performance and almost everything the organization does that is experienced in the service encounters or elsewhere has an impact on the customer. Moreover, the various means of communication and their effects are interrelated. These communication effects, together with other factors such as the technical quality of the service, shape the image of the organization in the minds of customers, and potential customers. We shall return to the issue of image management and branding in the next chapter.

INTEGRATED MARKETING COMMUNICATIONS

The integrated marketing communications notion emerged as an approach to understanding how a holistic communications message could be developed and managed.2 As the total communication concept, it is based on the notion that it is not only planned communication efforts using separate and distinct communications media, such as TV, print, direct mail, the Internet, or social media, etc., that communicate a message about the firm and its offerings to customers and potential customers. Although these are communication activities that can easily be planned and implemented by the marketer, other aspects (for example, how the service process functions, what resources are used and what physical products are used in the process) include an element of communication. The messages that these parts of the customer relationship send may be more effective than those that the customer receives from advertisements, brochures and other traditional marketing communications media. However, to an overwhelming extent the literature on integrated marketing communication only includes communication media where communication activities can be planned distinctly as communication.

Furthermore, as conventional marketing communication is basically a firm-driven process, what is communicated is expected to be perceived more or less as intended. Obviously, in reality it may not be like this. A customer-driven communication approach is presented later in this chapter.

As a true total communications approach, integrated marketing communications, which is still firm-driven though, can be defined as follows:3

Integrated marketing communications is a strategy that integrates traditional media marketing, direct marketing, public relations and other distinct marketing communications media as well as communications aspects of the delivery and consumption of goods and services and of customer service and other customer encounters. Thus, integrated marketing communications has a long-term perspective.

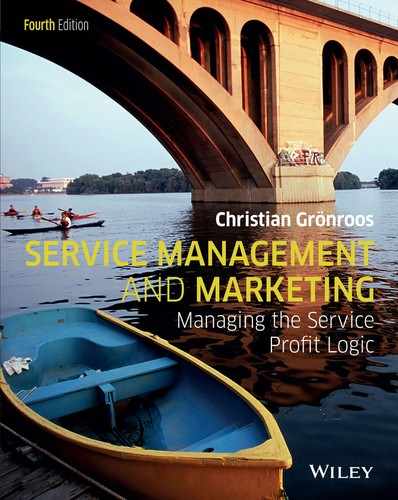

According to this definition, communication messages can originate from several sources. Duncan and Moriarty distinguish between four kinds of sources of communication messages:4

Planned messages.

Product messages.

Service messages.

Unplanned messages.

Planned messages are the result of a planned marketing communications campaign where separate communications media, such as TV, print, direct mail, the Internet, social media, etc., are used to send a message. Sales representatives also communicate planned messages. Generally, these messages are the least trustworthy, because people know that they are planned by the marketer to persuade customers and potential customers in a certain direction.

Product messages are messages about the firm and its offerings that follow from the physical products in an offering: how a physical product is designed, how it functions, how it can be disposed of, etc.

Service messages are messages that result from service processes. The appearance, attitude and behaviour of service employees, the way systems and technology function, and the servicescape all send service messages. Interactions between customers and service employees in the service process include a substantial element of communication. Not only can the customer get valuable information in these encounters, he may also develop a sense of trust in the firm based on such interactions. On the other hand, the effects may also be negative. How the systems function and how the servicescape supports the service process also communicate something and may build up trust in the firm. One might say that service messages are more trustworthy than planned messages and product messages, because customers know that it is more difficult to manage the resources that create such messages than it is with planned messages and product messages.

FIGURE 10.1

Sources of communication messages.

Source: Developed from Duncan, T. & Moriarty, S., Driving Brand Value. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1997.

Finally, there are unplanned messages, which are considered to be the most trustworthy. Unplanned messages about the firm and its offerings are sent by fellow customers who interact with a given customer during the service process or who make comments in social media and convey good or bad word-of-mouth communication or, for example, by articles in newspapers, magazines or in TV programmes.

In Figure 10.1 these four types of sources of communication messages, as well as examples of the various types of messages, are summarized. To the far right in the figure a fifth source of communication message has been added. As Henrik Calonius5 suggested, absence of communication in critical situations, such as when service failures or other unexpected events have occurred, can have a profound influence on the customer’s perception of service quality. If the marketer does not say anything, for example, about how long a delay can be expected to take or when a delayed shipment can be expected to arrive, customers are kept out of control of the situation. This almost always has a negative effect on perceived service quality, adds psychological relationship costs and hurts a relationship.

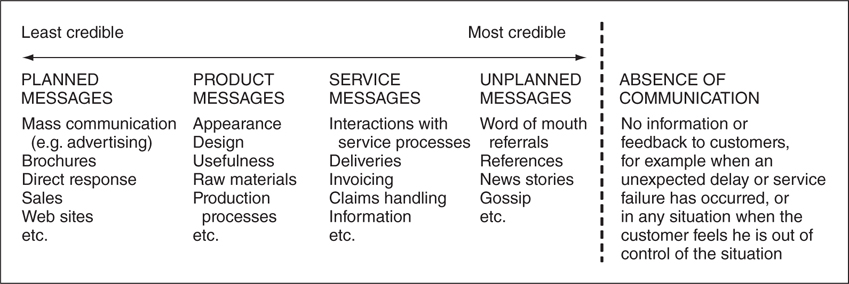

As is illustrated in Figure 10.2, the sources of these four types of messages, in addition to absence of communication, can be described as ‘What the firm says’ (in planned communications messages), ‘What the firm does’ (creating product and service messages) and ‘What others say and do’ (fellow customers in the service process, word of mouth, social media comments and conservations, and media coverage in the form of articles and TV programmes).

A major problem in marketing communication is the fact that only the least trustworthy source of messages about the firm and its offerings – planned messages (‘What the firm says’) using distinct communications media – is normally planned as part of the marketing communications programme. Product messages may partly be planned, whereas the more trustworthy sources, service messages and unplanned messages (‘What the firm does’ and ‘What others say and do’) are largely ignored. The fact that these types of messages are not part of an organized marketing communications process and not covered by a budget for marketing communications does not mean that their communications impact would be low. However, firms tend to neglect them, because they are difficult to plan. It is much easier to spend even more money on developing planned messages and using advertising, direct mail, sales promotions and other traditional means of marketing communication as well as the Internet and other new media. The effect of such a communications strategy is not guaranteed.

FIGURE 10.2

The total communication/integrated marketing communication triangle.

Source: Adapted from Grönroos, C. & Lindberg-Repo, K., Integrated marketing communications. The communication aspect of relationship marketing. Integrated Marketing Communications Research Journal, 4(1); 1998: 10.

The challenge to a firm is to manage all sources of messages about the firm and its offerings and all the communication media and their effects in an integrated way. Otherwise, customers will receive different, possibly contradictory, signals from the various types of communication. A salesperson may promise one thing while a personalized sales letter may promise something else (both planned communication messages), and a third communication effect may emerge when the customer perceives reality in the service encounter when consuming the service (effect of service messages). Furthermore, somewhere along the line there may be an absence of communication, either deliberate or accidental, which adds to the confusion of the total communication effect.

On the other hand, the organization that masters total communication management can achieve a powerful market communication impact, which adds substantially to the performance of the total marketing process. It is a way of boosting image and has a significant effect on word-of-mouth communication.

THE ABSENCE OF COMMUNICATION

As mentioned, there is a fifth source of message or type of communication that has to be considered when planning total communication, and that is the absence of communication.6 This is often mistaken for lack of communication, where nothing is communicated.

The absence of communication may send messages as effectively as planned communication does. When a firm decides not to inform its customers about, say, a delay or a quality fault, this is not simply a lack of communication. Instead, there is a distinct message involved. This is perceived either immediately or later. It tells the customer that the service provider or supplier does not care about the customer and that the firm cannot be trusted. Absence of communication is frequently perceived as negative communication.

When a customer observes that there is a problem – for example, a flight does not leave on time or delivery of merchandise does not arrive on time – and the firm remains quiet, he loses control of the situation. Customers consider it important to be in control.7 Being in control of a negative situation such as a delayed shipment makes a customer more trusting towards the supplier than not knowing what has happened. Also, keeping the customer informed about problems and deviations from what was expected is a way of showing respect. Openly recognizing a service failure is also the first step in a service recovery process and, as we have discussed previously, successful service recovery is a criterion of good functional quality.

In conclusion, the absence of communication may send a dangerous negative message about the firm. Normally, even negative information is better than no information.

WORD OF MOUTH AND THE COMMUNICATION CIRCLE

The marketing impact of word-of-mouth communication is usually huge, frequently greater than that of planned communication. This impact has been growing exponentially due to the Internet and since the introduction of social media. Word of mouth means messages about the organization, its credibility and trustworthiness, its ways of operating, its offerings and so on are communicated from one person to another, or through digital media to groups of other persons. As service is often based on an ongoing customer relationship, it is useful to understand word of mouth in a relationship context:

Word of mouth communication from a relational perspective is based on consumers’ long-term experiences and behavioral commitment. Their word of mouth communication reflects the nature and value of their perception of relationship episodes or service encounters, as well as psychological comfort/discomfort with the relationship. It varies depending on how strong the relationship is.8

In the eyes of a potential customer, a person who has had personal experience with the service provider is an objective source of information. Consequently, if there is a conflict between the word-of-mouth message and, say, an advertising campaign, advertising will lose.

If a strong relationship develops with a given customer, advocacy bonds between the firm and the customer may also develop. Such customers recommend the firm to their friends, colleagues, etc., and on social media even to complete strangers, whereby they thus invite others to share the service experience with them.9 They become advocates of the service offering. When offering word-of-mouth referrals customers with only one or a few experiences from a service will probably emphasize the price of the service, whereas long-standing customers are more likely to talk about the value of the service.

The amount of word-of-mouth referrals also seem to correlate positively with the relative growth of a firm in its industry. The more a firm’s customers enthusiastically recommend the firm and its products to others, the better the growth rate of that firm. As growth can often be expected to be a key driver of profitability, a large number of advocates on the market who refer the firm to other people also makes sense from a business profitability point of view.10

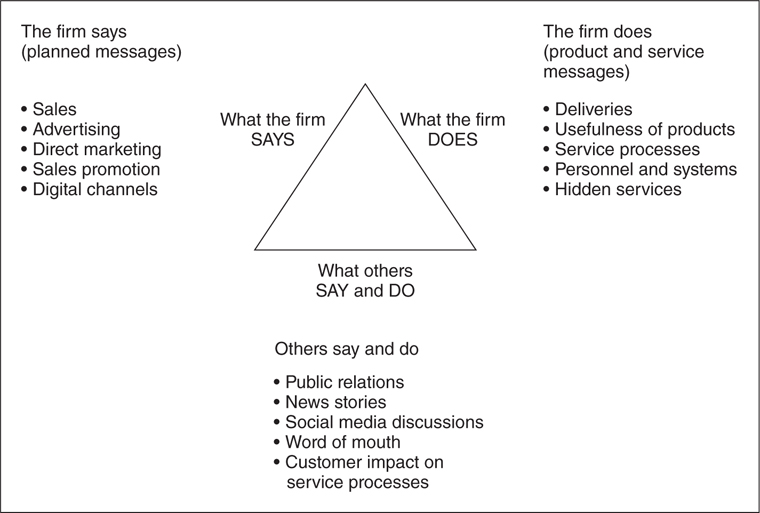

FIGURE 10.3

The communication circle.

We will not go into word of mouth in any further detail here. Instead, we will turn to the communication circle, in which word of mouth in all its forms plays a critical role. This circle is illustrated schematically in Figure 10.3.

The communication circle consists of four parts, expectations/purchases, interactions/service encounters, experiences and word of mouth and references/social media. A potential customer or existing customer has developed certain expectations and therefore may decide to make a purchase; new business is created or an ongoing customer relationship thus continues, respectively. Having done so, he moves into the consumption stage of the customer relationship lifecycle. At this point, the customer gets involved in interactions with the organization and perceives the technical and functional quality dimensions of the service rendered. These interactions usually involve a high number of moments of truth or moments of opportunity. Here the customer is exposed to the interactive marketing efforts of the firm and receives service and product messages. The way the employees perform and systems function communicates a number of messages about the firm, its trustworthiness, its interest in customers, etc.

Now, the experiences that follow from a customer being involved in interactions in the service encounters and perceiving the quality dimensions multiply several times by means of word of mouth and comments and conversations on social media. If the message thus communicated is positive, customer expectations develop favourably. The customer with positive experiences is more inclined to return or continue to use the service on an ongoing basis. New potential customers become interested in the organization and its offerings. References (and testimonials) represent an active way for the firm to use positive word of mouth in its marketing, thus capitalizing more effectively on potential sources of good word of mouth.

The multiplier effect of word of mouth varies between industries and situations. It is frequently claimed that negative experiences tend to multiply by word of mouth quicker and more often than do positive experiences. And through social media these effects grows exponentially. Although there is no research to show the magnitude of this multiplying effect, the trend is clear and sends the marketer a blunt message: Do not play with word of mouth. Make it work for you in all situations, and always try to capitalize on it. From the marketer’s perspective it is difficult, almost impossible, to steer word of mouth and discussions on social media directly. Attempts to interfere with such discussions almost invariably backfire. Word of mouth in all its forms can only be managed indirectly, by eliminating mistakes and negative customer experiences, and when service failures sometimes happen, by recovering the failure properly in a customer-centric manner.

Thus, word of mouth has a powerful impact on the formation of expectations of existing and potential customers and is an important determinant of future purchasing behaviour. On the one hand, good word of mouth has a positive effect on expectations and future purchases. On the other hand, negative word of mouth has, of course, the opposite effect.

MARKETING COMMUNICATION AND THE COMMUNICATION CIRCLE

It is important that the existence of the communication circle be understood and its implications fully appreciated by the marketer. If customer interactions create too many negative experiences and negative word of mouth follows, the customer builds up a resistance to active marketing communication. The more negative word of mouth there is, the less effective advertising campaigns, direct communication and sales efforts will be, and the less inclined people will be to look at the firm’s website. More has to be invested in these types of communication if the negative impact of word of mouth is to be nullified. If too many negative messages are communicated by word of mouth and the image of the organization suffers severely, no increase in the marketing communication budget will be enough to save the situation, at least not in the long run.

Positive word of mouth, on the other hand, decreases the need to spend so much on marketing communication, through, for example, advertising and sales. It also draws customers and potential customers to Internet sites, either because they are looking for solutions to a problem, or simply out of curiosity. Good experiences and favourable word of mouth take care of much of the new business that is needed. In theory, excellent interactions, including good customer perceived quality and interactive communication, make mass communication less necessary and allow more freedom in pricing. Only when totally new services are launched may mass communication such as advertising campaigns be needed. There are numerous examples of small local firms that operate successfully in this way, and larger firms operating in larger areas can do the same. One of the leading banks in Scandinavia, Svenska Handelsbanken, has pursued such a communication strategy for over 40 years, and it has worked well; the profitability of the bank as well as customer satisfaction have constantly been well above average.

Whatever communication strategy the organization adopts, the key to successfully executed marketing communication is how the interactions between the organization and its customers have been geared to the needs and wishes of customers and to producing excellent perceived quality and building up supportive word of mouth. If the communication aspects of interactions are neglected, the interactive communication impact will not be as good, and could even be negative. As a consequence, more money will be needed for other types of communication, and even this may not be enough.

If marketing communication efforts sending planned messages through, for example, personal selling, mass communication and direct mail are developed without being geared to the communication effects of the service encounter (service messages) and word of mouth, the risk of overpromising and, consequently, of building up quality gaps grows substantially. Customers will then meet a reality that does not correspond to their expectations. This, in turn, destroys the communication circle, and three types of negative consequences may follow:

Word of mouth and references will become negative; negative discussions on social media are triggered.

The trustworthiness of the organization’s communication messages suffer.

The firm’s image is damaged.

On the other hand, if all elements of the communication process and customer perceptions of the service encounters are good, the corresponding effect is, of course, the opposite. Good word of mouth is built up, the credibility of the marketing communication efforts increases, and image improves.

To sum up, only a total communication management approach, where the effects of various sources of communication messages are integrated as well as possible, will be effective and justified from a management point of view. The effects of all types of communication, including the absence of communication, have to be taken into consideration. Integrating the different types of marketing communication and sources of messages is not an easy task. This is, however, not a valid excuse for not trying to integrate as much as possible. However, there is sometimes a structural obstacle in firms. Marketing communication is normally managed on a low level in the organizational hierarchy, where, for example, a marketing communication manager or even a marketing manager cannot integrate more than the planned communication messages.

PLANNED AND UNPLANNED COMMUNICATION

Unplanned messages were discussed in a previous section. These are messages from sources that cannot be planned or are difficult to plan. There is also another aspect of the planned/unplanned issue. Even planned messages may go partly unplanned. Hence, we can talk about unplanned communication as well as planned, depending on how well the marketer manages to plan all aspects of a planned message, or of a product or service message.

Unplanned communication, as opposed to planned communication, has a distinct effect just like the absence of communication.11 There are often a number of situations where communication effects occur, although these situations have not been planned from a communication point of view. Such unplanned communication effects may be caused by planned messages in sales negotiations, advertising or some other distinct communications media, or they may be related to product or service messages.

Unplanned communications can easily have a negative impact on customer perceptions. Therefore, it is important to analyse all sources of communication and their possible effects, planned as well as unplanned. In Table 10.1 examples taken from various situations illustrate how unplanned communication effects may occur.

In practical situations it is, of course, seldom possible to exclude all sources of unplanned communication. However, successful total communications management requires that as many as possible of the potential communication situations be planned and the risk of unfavourable unplanned communication at least minimized.

Planned and unplanned communication.

Type of communication |

Planned |

Unplanned |

Personal selling |

Good travel plans Good advice |

Sloppy dress Uninterested in our values |

Mass communication |

Target-group directed advertising Informative menus |

Communicates values that offend the customer |

Direct communication (direct mail) |

Correct address Personalized content |

Wrong first name Irrelevant information |

Websites |

Easy to find interesting links & e-mail contact opportunities |

No or delayed answers to e-mails |

Communication in service encounters (service messages) |

Good manners Pleasant servicescape Effective systems |

Snooty Badly maintained premises Complicated technology |

Communication by physical products in service processes (product messages) |

High-class amenities in a hotel room |

Plastic chairs in an outdoor café |

Absence of communication |

‘We don’t give any information unless it is correct’ ‘We’ll inform you as soon as we know more, and let you know the situation every 10 minutes anyway’ |

Neglecting to inform customers about delays |

THE SHORT-, MEDIUM- AND LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF MARKETING COMMUNICATION

Frequently, marketing communication is only used to achieve short-term goals. Sometimes efforts are made to create more enduring effects, for example, corporate advertising campaigns or image communication programmes. Too often, however, such long-term efforts are planned separately from other campaigns. Every communication activity, whether short-term or long-term, has effects on customers, as well as on potential customers and employees in a number of different time perspectives.

We are here going to distinguish between three time perspectives and their impacts on how an organization is perceived in the marketplace:

A marketing communication impact in the short term.

A marketing impact in the medium term.

An image impact in the long term.

Every communication effort, such as an advertising campaign, an Internet site, the behaviour of service employees, or the ease with which an ATM is operated, has an instant, short-term communication impact as a communication activity. This may be very effective as a means of communication; for example, a well-planned and executed advertising campaign that makes potential customers believe in the promises made. However, over a longer period the effects may be less clear, even negative. Another thing that is important to bear in mind is that mass communication has an impact on several target groups, even though it may be planned for and directed at only, say, potential customers. Existing customers and the firm’s employees are also exposed to such communication. For example, potential customers to whom the firm may promise discounts or special benefits if they make a purchase may be impressed, whereas the firm’s existing customers may be annoyed. Such problems should be recognized by the marketer in advance and avoided from the beginning in the planning process.

In Table 10.2 the possible effects of such an effective advertising campaign (or any type of communication effort) involving overpromising are illustrated: ‘+’ denotes a favourable effect, ‘–’ a negative effect and ‘0’ a neutral effect or no effect. Three target groups for this campaign, customers, potential customers and employees, are identified and the impact on these groups indicated. In reality there may be more target groups. In Table 10.2 and then in Table 10.3 traditional planned communication is used to exemplify the various effects of marketing communication. Similar analyses can, and should, be conducted for product and service messages, and also for unplanned messages and even for absence of communication.

Effects of an effectively executed communication campaign involving overpromising in three time periods at three levels.

Effect/period of time level |

Target groups |

||

Existing customers |

Potential customers |

Employees |

|

Short term: effect of campaign as communication |

+ or 0 ‘Maybe they really mean it!’ |

+ ‘This sounds good!’ |

0 ‘I doubt it!’ |

Medium term: effect of campaign as part of marketing |

– ‘I should have known better! Cheated again!’ |

0 or – ‘Wasn’t it more than this?’ or ‘This is not what I expected!’ |

– ‘It’s as I thought and I have had to explain why we cannot fulfil our promises!’ |

Long term: effect of campaign on image formation |

–– ‘They never do what they say they are going to do!’ |

–– ‘They just talk and promise.’ |

–– ‘I’m looking for another employer.’ |

Effects of realistic market communication in three time periods at three levels.

Effect/period of time level |

Target groups |

||

Existing customers |

Potential customers |

Employees |

|

Short term: effect of campaign as communication |

+ ‘They have something new to offer.’ |

+ ‘It sounds interesting.’ |

+ ‘We are prepared!’ |

Medium term: effect of campaign as part of marketing |

++ ‘What a good service!’ |

+ ‘They really fulfilled their promises.’ |

+ ‘It works out well.’ |

Long term: effect of campaign on image formation |

++ ‘That’s my service provider!’ |

++ ‘You can really trust them.’ |

++ ‘This is the best employer I’ve ever worked for.’ |

As can be seen from Table 10.2, this hypothetical advertising campaign obviously includes promises that cannot be fulfilled. For potential customers and even for existing customers, the effects of this campaign may be positive in the short term seen as a communications effect only, if it is well executed. However, employees, who know they cannot possibly fulfil such promises, react differently. If this is the first time such overpromising takes place, they will probably react in a neutral way and the campaign will have no effect. However, if such overpromises have been made in the past, their reactions will be negative.

Over a longer period of time, as customers and potential customers get involved in interactions with the organization, the perception of this advertising campaign changes. They realize that reality has not met their expectations and the promises made by the campaign. The combined impact of the advertising campaign as a traditional marketing effort and the interactive marketing effect of the buyer–seller interactions in the service encounters, which are inconsistent with the campaign, thus changes the positive effect of the campaign. This combined effect is the impact of the total marketing process, including traditional as well as interactive activities, and it is probably negative. The customers feel cheated, and justifiably so. Hence, in the medium term, the marketing effect of a campaign, which judged in isolation may seem good and effective, can be poor or directly negative.

As far as the employees are concerned, the medium-term effect is definitely negative, because they will have to cope with customers who have unrealistic expectations and may get angry and sometimes even nasty towards them. Personnel are put in an awkward position, which damages employee motivation and good interactive marketing performance.

Finally, we can stretch the time perspective even more, and observe the possible long-term effects of this advertising campaign. If the campaign runs for a longer period of time, or is followed by other campaigns which also overpromise, customers and potential customers will learn that the organization is not trustworthy. Over the long term, single communication campaigns that, again judged in isolation, look like good communication may have a very negative impact on the image of the organization.

Of course, employees react as strongly as customers. Dissatisfied customers can normally leave a company with little or no notice, whereas it may be less easy for many employees to find a new employer. In the long run employee motivation suffers badly.

The effects of a trustworthy communication campaign that does not involve overpromising are, of course, totally different. Table 10.3 illustrates the effects that can be expected to occur when, for example, an advertising campaign is run which makes realistic promises. Customers exposed to the messages of this campaign experience a reality that corresponds to the promises, if they decide to buy and consume service provided by the organization.

The effects demonstrated in Table 10.3 are totally different from those in Table 10.2. In the short term, existing and potential customers and employees can be expected to react positively. This initial favourable effect is enhanced by the fact that the service production process is perceived to be in line with the campaign. Interactive marketing in the service encounters and the market communication campaign support each other. In the long term, image is improved by the fact that the organization consistently gives a good impression, by marketing communication as well as by reality and interactive marketing performance. In terms of the relationship marketing model in Chapter 9, activities in the planned communication process (planned messages) and in the interaction process (product and service messages) support each other. As a consequence, this will trigger positive unplanned communication (word of mouth, comments on social media, news stories). The employees also react favourably. In the long term, they will probably consider their employer the best possible, if other internal activities or policies do not destroy this impression.

As these examples demonstrate, it is imperative that every communication effort is judged not only on its virtues as a communication effort, but in a much larger perspective, otherwise unwanted effects may occur.

GUIDELINES FOR MANAGING MARKET COMMUNICATION

Some general guidelines for managing market communication can be identified.12 Here 12 guidelines are discussed:

Direct communication efforts to employees.

Capitalize on word of mouth.

Provide tangible clues.

Communicate intangibility.

Make the service understood.

Provide communication continuity.

Promise what is possible.

Observe the long-term effects of communication.

Be aware of the communication effects of the absence of communication.

Integrate marketing communication efforts and messages.

Customers integrate communication messages with their previous experiences as well as with their life experiences and expectations.

In the end, it is the customers who create messages for themselves out of a firm’s communication efforts.

Direct communication efforts to employees. All advertising campaigns and most other mass communication efforts that are planned for various segments of existing and potential customers are also visible to employees. Employees are therefore an important ‘second audience’ for these campaigns. Promoting the position of employees in external communication campaigns is a way of internally enhancing the employees’ roles and adding to their motivation.

Capitalize on word of mouth. As demonstrated by the discussion of the communication circle and the vital role of word of mouth and customer references, good word of mouth makes customers more receptive to external marketing communication efforts, and vice versa. Moreover, good word of mouth can be considered the most effective communication vehicle. Therefore, if a firm has created good word of mouth, which is a message from an objective source (satisfied customers), it is a good idea to use the objective nature of word of mouth in marketing communication. Testimonials are examples of this.

Provide tangible clues. As services are intangible, communicating information about a service, especially to an audience of potential customers, can be very difficult. The intangible service can easily become even more abstract. Therefore, it is a good idea to try to make the service more concrete. For example, a firm may illustrate or demonstrate tangible items that are either involved in the service production process or relate to the service. This is a way of demonstrating the quality of the service. Showing the physical comfort of first class travel on an airline in an advertisement may be a more effective way of giving potential customers something tangible to relate to and remember than an abstract visualization of luxury.

Communicate intangibility. Although it is often possible to offer tangible clues to a service, one should bear in mind that service is intangibly perceived. Emphasizing a tangible component in the service process, such as silverware and flatware for a first class or business class airline service, may not always differentiate a service in a meaningful way. Instead, the challenge is sometimes to be able to cope with the intangibility of the service, because the differentiating appeal may be found in some aspect of the intangibility of the service. Showing parts of the service process, for instance, a customer enjoying his leisure time at a beach while being on an inclusive vacation or presenting testimonials of satisfied customers, are examples of how to communicate intangibility of services.13

Make the service understood. Because of the intangible nature of service, special attention has to be paid to making the benefits of a particular service clearly understood. Using abstract expressions and superlatives may not lead to a good communication effect. The service and what it can do for the customer remains unclear. Therefore, it is important to find good metaphors that clearly communicate the service.

Provide communication continuity. Once more, because service is intangible, and because mass communication about service is difficult for the audience to grasp, there has to be continuity in communication efforts over time. A common tune in a TV or radio commercial or a common layout, picture or phrase in a newspaper advert, which continues from one campaign to the next, may be a way of making the audience realize more quickly what is advertised and what the message is. Typically, marketers feel that a communication theme is out of date and ready to change, just when the target audience has started to realize what the message is all about. In service, the marketer needs more patience than in the communication of physical products.

Promise what is possible. If promises given by external market communication are not fulfilled, the gap between expectation and experience is widened, and customer perceived quality decreases. It is often said that keeping promises is the most important single aspect of good service quality. Clearly, avoiding overpromising is essential in managing marketing communication. This has a clear connection with the next guideline.

Observe the long-term effects of marketing communication. As the discussion in the previous section demonstrated, a communication campaign that seems to be effective may have unexpected, negative effects when viewed over the long term. If promises that cannot be fulfilled are made, the short-term effects on sales may be good, but customers will become dissatisfied as they perceive reality. They will not return but will create bad word of mouth. Over the longer term, the image of the organization is damaged. The effects on employees are similar. Hence, a long-term perspective must always be taken when external marketing communication is planned and executed.

Be aware of the effects of the absence of communication. If there is no information available in a stressful situation, customers often perceive this as negative information because they lose control of the situation. It is usually better to share bad news with customers than to say nothing.14

Integrate marketing communication efforts and messages. As a previous discussion in this chapter demonstrated, customers are exposed to a number of different communication messages. These messages may be conflicting, thus creating a confusing impact. If communication messages through, for example, advertising, direct mail and the messages the service process are sending are contradictory, the effect is not trustworthy and the image of the firm may be damaged. Hence, it is important for the marketer to try to integrate all types of communication messages – planned, product, service and unplanned – so that customers know what the firm stands for and can develop a trusting relationship with it.

Customers integrate messages with their previous experiences and life expectations. No communication message exists in a vacuum. A customer has experiences of the firm or its services or goods from before and he may even feel that there is at least some kind of relationship with the firm. The perception of the communication message from, for example, an advertisement or service interaction is merged with these previous experiences and the image of the firm and its solutions that have developed in the customer’s mind. The message that is formed in this way is probably at least somewhat different from what the firm intended it to be and it may even be vastly different.15 Likewise, the customer’s life situations, history and expectations will probably have an impact on the message he perceives. This impact may even be profound. This means that different customers will interpret the same communications effort, for example an advertisement, in very different ways.16

In the end it is the customers who create the message out of a firm’s communication efforts. Most marketing communications models state that, except for the distorting effect of some noise in the communication flow, the message sent by the marketer equals the message received by the customer. Marketers often tend to act as if the message sent is also the message understood by customers. In reality it is the customer who constructs the message for himself. Every message is personal. It is highly questionable whether one can even say that marketers send messages. What marketers perhaps do is create inputs of various sorts for each and every customer’s personal message creation mechanism. This mechanism is in the mind of the customer, and the creation process depends on the relationship history and future expectations of a given customer as well as his life history and expectations. Furthermore, it depends on environmental effects, for example what a competitor does at a given moment or changes in the customer’s life situation.17 For example, in the case of service interactions the service contact employees can attempt to take a customer’s personal situation, his relationship history and expectations, and possibly even his life situation, into account as much as possible. In this way the communication effect of the interaction will probably improve. In direct communication, for example using direct mail, this is also possible to some extent. In mass communication, to improve the effect of communication efforts, the marketer will have to make use of information about customer segments.

DEVELOPING A RELATIONSHIP DIALOGUE

In an ongoing relationship context it is not only the firm that is supposed to talk to the customer, and the customer who is supposed to listen. It is a two-way street, where both parties should communicate with each other. In the best case a dialogue develops.18 A dialogue can be seen as an interactive process of reasoning together.19 In the words of Ballantyne and Varey, ‘marketing’s unused potential is in the dialogical mode’.20

The purpose of a dialogue is for two parties to develop a better mutual understanding of a problem and eventually to solve this problem. Hence, two business parties should reason together in order to understand a problem, and if possible find a solution to it. The process of reasoning together includes the willingness of both parties to listen and an ability to discuss and communicate for the sake of achieving a common goal. As Ballantyne and Varey conclude, ‘in a dialogue participants speak and act between each other, not to each other’.21

A connection between the firm and the customer has to be made, so that they find they can trust each other in this dialogue or reasoning process. The intent of this process is to build shared meanings, and develop insights into what the two parties can do together and for each other through access to a common meaning or shared field of knowledge.22

A dialogue requires participation of the parties involved.23 Participation takes place not only in interactions between the firm and its customers, but also through one-way communication efforts, such as advertisements, brochures and direct mail as well as one-way Internet communication. Messages through these traditional communication media using old and new technologies should, however, contribute to the development of shared meanings and common fields of knowledge. When such messages through impersonal media and interactions between the customer and the firm support each other, the two parties are reasoning together.

There is a difference between one-way and two-way communication through impersonal media as part of a dialogue. One-way communication has a sender and a receiver of messages sent. A dialogue requires the participation of the parties involved, and hence, in a dialogue there are no senders or receivers, only participants in the dialogue process. Therefore, a dialogue resembles a discussion more than communication in a traditional sense.

Sometimes marketers send out a direct marketing letter where they invite a response from the receiver. If the receiver reacts by responding, this is taken as the beginning of a dialogue or even as the manifestation of a dialogue. However, creating a dialogue between a firm and a customer takes much more effort than this. A dialogue is an ongoing process, where information should be exchanged between the two parties in a way that makes both the firm and the customer ready to start or continue doing business with each other. Both parties have to be motivated to develop and maintain a dialogue, otherwise no real dialogue will develop.24 Instead of a dialogue, two parallel monologues or perhaps only one monologue without a listener will take place. This, of course, goes for individual consumers as well as for firms.

To maintain a dialogue not all communication contacts between the parties have to include an invitation to respond. An informative brochure or even a plain TV commercial may be part of an ongoing dialogue, provided that the customer perceives that it gives information which is valuable for him to proceed in the relationship: for example, it tells the customer what piece of advice to ask for or gives him information needed to make the next purchase. It is also important to remember that it is not only planned communication through planned communication media (TV commercials, newspaper ads, brochures, direct mail, Internet communication, sales representatives, etc.) that maintains a dialogue. In a relationship the other sources of communication which were discussed earlier in this chapter (product and service messages, unplanned messages such as word-of-mouth referrals and public relations and the absence of communication) also send messages which influence the dialogue. Goods, service processes and interactions with fellow customers during the various service encounters contribute to the firm’s total communication message, and thus are all forms of input into an ongoing relationship dialogue.

In the relationship marketing model in Chapter 9 (see Figure 9.4) two parallel processes – a communication process and an interaction process – constitute the relationship process. Using this model, a relationship dialogue can be illustrated, and the quality of such a dialogue can also be analysed. For example, a customer calls a helpdesk because he has been advised to do so in a newspaper ad or in a brochure, and he receives attentive service and the required information. This is a good two-step sequence of distinct communication (advert or brochure) and service messages (helpdesk support), which favourably supports the development of a relationship dialogue. A customer may also have answered a direct mailing and in return received a brochure describing quick and attentive service. Following this sequence of dialogue-oriented distinct communication messages with the customer’s response in between the two messages, the customer decides to purchase the service and enters into interactions with employees and systems in a service process. There he realizes that the service does not fulfil the promise of quick and attentive service. There are, for example, too few customer contact employees and they do not have the time or desire to show a genuine interest in the customer’s problem. What started out as a positively developing dialogue is damaged by the negative message following the customer’s bad experiences with the service encounter. Messages from the communication process and the interaction process have not supported each other and, consequently, no favourable relationship dialogue developed in the long run.

A successful development of a relationship requires that the two (or more) parties continuously learn from each other. The supplier or service provider acquires a constantly growing understanding of the customer’s needs, values and consumption or usage habits. The customer learns how to participate in the interaction processes in order to get quick and accurate information, support, personal attention, well-functioning service, etc. This process can be characterized as a learning relationship.25

An ongoing dialogue supports the development of a learning relationship. However, if the collaboration between a supplier and a customer does not include elements of learning, a relationship dialogue will not develop. In fact, no real relationship will develop where the parties involved do not feel that a mutual way of thinking exists. The customer may still continue to buy from the same supplier or service firm, at least for some time, perhaps because the seller offers a low price, has a technological advantage over competing firms, or is conveniently located. However, this relationship is much more vulnerable to changes in the marketplace, to new competitors and to new alternative solutions that may become available.

INTEGRATED MARKETING COMMUNICATION AND RELATIONSHIP MARKETING

Simply planning and managing marketing communication through distinct communications media, even as a two-way process, is not relationship marketing and probably does not create a dialogue, although communication efforts may look relational, such as personally addressed letters inviting a customer response. The marketer and the customer are not reasoning together to build up a common meaning. Only the planned integration of distinct planned communication and interaction processes into one systematically implemented strategy creates relationship marketing. A true integration of the various marketing communication messages with each other and with the outcomes of the interaction process is required for the successful implementation of relationship marketing. Only in this way can an ongoing relationship between the firm and its customer dialogue, which is a key element of relationship marketing, be maintained.

As the relationship proceeds, the different types of messages develop in a continuous process and their effects accumulate in the minds of customers. If the distinct communication process with its planned marketing communication is supported by the product and service messages created in the interaction process, favourable unplanned communication resulting in positive word-of-mouth communication will occur.26

Both the firm and the customer should be motivated to communicate with each other. The customer should feel that the firm which sends a message is interested in him and argues convincingly for their service. In such a situation the planned communication efforts and the communication aspects of the interaction process merge into one single two-way communication process, which constitutes a relationship dialogue with the customer and the supplier or service provider as participants. The nature and content of word-of-mouth referrals will probably differ depending on how long the customer has been involved in the interaction process. It can be assumed that referrals by a longstanding customer will include more holistic expressions (such as ‘It’s a great company’) than detailed experiences, and more value-oriented than price-related expressions.27

RELATIONSHIP COMMUNICATION

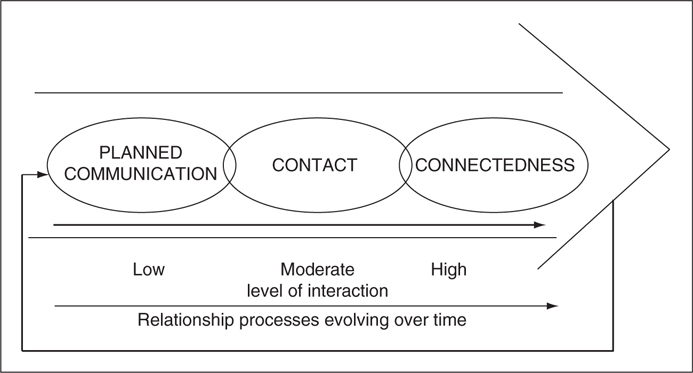

In order to develop a relationship with its customers the firm has to turn to a long-term dialogical communication approach. When the firm and its customer ‘reason together’ about how the customer’s everyday activities and processes can best be supported and a mutual knowledge about how this can be done is emerging, the likelihood increases that a mutual understanding and commitment develops between the customer and the supplier or service provider. The possibility of reaching the marketing objective of getting not only a ‘share of the customer’s wallet’ but also a ‘share of his heart and mind’ grows. In Figure 10.4 a trimodal conceptualization of relationship communication is illustrated.28 The model includes three levels: planned communication, contact and connectedness.

The relationship communication process proceeds from a low level of interaction between the seller and buyer towards higher levels of interaction. In the first phase, communication activities are mostly planned communication using distinct communication media, for example, advertisements, brochures and direct mail as well as sales negotiations. As the process moves on the customer becomes involved in interactions with the firm, for example interacting with service employees and various systems representing the firm or interacting with physical goods. If these interactions successfully support the customer’s everyday processes, a contact beyond the mere planned communication messages is established. Product and service messages are intertwined with planned communication messages, and if the outcome is a successfully integrated message, the first steps towards dialogical communication have been taken. As the process moves on over time and two-way communication efforts increase, the communication that takes place can be characterized as dialogical and relational. As a result, a state of connectedness between the two parties is emerging. At this stage of the relationship communication process the customer’s heart and mind may have been won and a true relationship established. As long as the activities taken by the other party are considered fair and supportive, the likelihood that the relationship continues is high.

FIGURE 10.4

A trimodal relationship communication model.

Source: Reprinted from Lindberg-Repo, K. & Grönroos, C., Conceptualising communications strategy from a relational perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 33; 2004: p. 233 with permission from Elsevier.

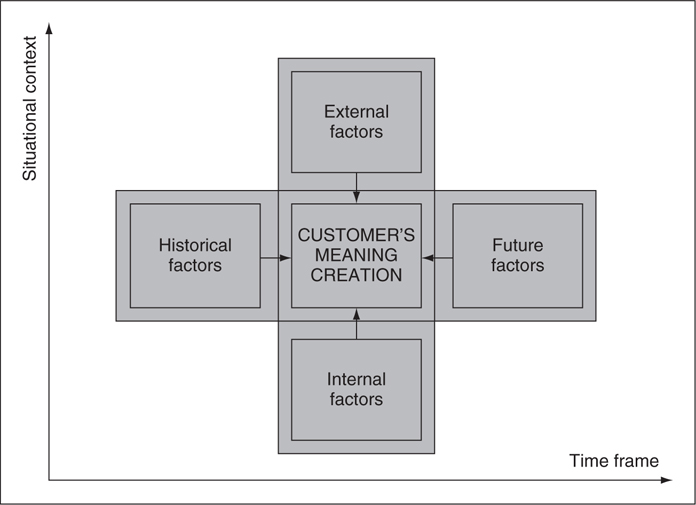

A relationship dialogue is aimed at as outlined above and shown in Figure 10.4. However, whether a communication effort is perceived as relationship communication is determined by the customer, not by the marketer. The customer assesses what meaning for him there is in a message (conveyed, for example, through an advertisement, brochure or direct contact in a service encounter). What the marketer thinks is relationship-oriented communication may be something else from the customer’s point of view. Finne and Grönroos suggest the following definition of relationship communication:29

Relationship communication is any type of marketing communication that influences the receiver’s long-term commitment to the sender by facilitating meaning creation through integration with the receiver’s time and situational context. The time context refers to the receiver’s perception of the history and envisioned future of his/her relationship with the sender. The situational context refers to other elements internal or external to the receiver.

From a relationship perspective, a communication message should have a positive impact on the customer’s commitment to the firm. However, whether this happens or not depends on the nature and content of the message and the customer’s temporal and contextual reality, or rather perception of reality. This is illustrated by the relationship communication model in Figure 10.5.

Conventional marketing communication models, also in the context of integrated marketing communication, assume that it is the marketer who determines what meaning a message conveys. The customer as a receiver is expected to accept this meaning, only somewhat distorted by some noise in the communication process. The relationship communication model, on the contrary, assumes that it is the customer who creates meaning out of communication messages. According to the model, this meaning is dependent on two factors: a temporal factor and a situational factor.30

FIGURE 10.5

Meaning creation in a relationship communication model.

Source: Finne, Å. & Grönroos, C., Rethinking marketing communication: from Integrated marketing communication to relationship communication. Journal of Marketing Communications, 15(2-3), 2009, 179-195. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis.

The temporal factors relate to the customer’s relationship with the firm. What are his experiences with the firm in the past, and what future expectations does he have about this relationship? The situational factors are either internal to the customer or external to him. Internal factors relate to an individual’s personality, education and level of knowledge, and the individual’s ‘life expectations’, etc. External factors can be culturally-situated factors or the personal context of the individual, such as family situation, economic situation and social situation, or trends, traditions, alternative choices, and also communication messages from competing firms, discussions on social media and word of mouth.

The customer relates any given communication message – an advertisement, sales call or interaction with a service employee – to the four temporal and situational factors of the model. Depending on how this assessment of the message turns out, this communication either has a positive or negative relationship-oriented meaning, or is not considered a relationship message at all. This assessment is, of course, often unconscious, but sometimes it may be very consciously conducted. From the marketer’s perspective, this means that a thorough analysis of its customers’ temporal and situational contexts should be done, before any communication plans are developed. Otherwise much of marketing communication may be unproductive, or even counterproductive, and relationship communication with the customers may not occur.

NOTES

1. This total communication concept was introduced in the 1980s. See Grönroos, C. & Rubinstein, D., Totalkommunikation (Total communication). Stockholm, Sweden: Liber/Marketing Technique Centre, 1986. In Swedish. In the early 1990s the same notion reappeared in the form of integrated marketing communications.

2. See Schultz, D.E., Tannenbaum, S.I. & Lauterborn, R.F., Integrated Marketing Communications. Lincolnwood, IL: NTC Publishing Group, 1992. For a more recent discussion of integrated marketing communication, see Kerr, G.F., Schultz, D., Patti, C. & Ilchul, K., An inside-out approach to integrated marketing communication: an international analysis. International Journal of Advertising, 27(4), 2008, 511–548, and Mulhern, F., Integrated marketing communication: from media channels to digital connectivity. Journal of Marketing Communications, 15(2–3), 2009, 85–101.

3. Grönroos, C. & Lindberg-Repo, K., Integrated marketing communications: the communications aspect of relationship marketing. Integrated Marketing Communications Research Journal, 4(1), 1998, 10. In a definition by the American Association of Advertising Agencies, as in almost every other definition, only traditional means of marketing communication, such as advertising, direct mail, sales promotion and public relations, are included.

4. Duncan, T. & Moriarty, S., Driving Brand Value. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1997.

5. Calonius, H., Market communication in service marketing. In Avlonitis, G.J., Papavasiliou, N.K. & Kouremeos, A.G. (eds), Marketing Thought and Practice in the 1990s. Proceedings from the XVIIIth Annual Conference of the European Marketing Academy, Athens, Greece, 1989.

6. Calonius, op. cit.

7. Hui, M.K. & Bateson, J.E.G., Perceived control and the effects of crowding and consumer choice on the service experience. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(Sept), 1991, 174–184. See also Bateson, J.E.G., Perceived control and the service encounter. In Czepiel, J.A., Solomon, M.R. & Surprenant C.E. (eds), The Service Encounter: Managing Employee/Service Interactions in Service Businesses. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1985, pp. 67–82.

8. Lindberg-Repo, K. & Grönroos, C., Word-of-mouth referrals in the domain of relationship marketing. The Australasian Marketing Journal, 7(1), 1999, 115. See also Lindberg-Repo, K., Word-of-Mouth Communication in the Hospitality Industry. Helsinki/Helsingfors: Hanken Swedish School of Economics, Finland/CERS, 1999. For a classical publication on word of mouth, see Arndt, J., Word of Mouth Advertising. New York: Advertising Research Foundation, 1969.

9. Lindberg-Repo & Grönroos, op. cit. For marketing in social media, see Evans, D., Social Media Marketing. An Hour a Day. Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

10. Reichheld, F.F., The one number you need to grow. Harvard Business Review, 81(12), 2003, 46–55. See also Keller, E., Unleashing the power of word of mouth: Creating brand advocacy to drive growth. Journal of Advertising Research, December, 2007.

11. See Calonius, op. cit.

12. Many of these guidelines are from George, W.R. & Berry, L.L., Guidelines for the advertising of services. Business Horizons, July–Aug, 1981, which still today is the best discussion of how to advertise service. Even though the authors focus on the advertising of service, their guidelines are useful in a larger marketing communications context as well.

13. The need to develop advertising and other ways of communicating, based on the intangibility of service, has been proposed by Benwari Mittal, who argues that intangibility may often offer better opportunities for differentiating a service in advertising than concentrating on tangible evidence. He discusses various strategies for communicating intangibility in advertising. See Mittal, B., The advertising of services. Meeting the challenge of intangibility. Journal of Service Research, 2(1), 1999, 98–116.

14. Grönroos, C., Service Management and Marketing. Managing the Moments of Truth in Service Competition. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990.

15. Finne, Å. & Grönroos, C., Rethinking marketing communication: from integrated marketing communication to relationship communication. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(2–3), 2009, 179–195.

16. See Mick, D.G. & Buhl, C., A meaning-based model of advertising experiences. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(Dec), 1991, 317–338.

17. Finne & Grönroos, op. cit.

18. See, for example, Fischer, A., Sieg, J.H., Wallin, M.W. & von Krogh, G., What motivates professional service firm employees to nurture client dialogues? The Service Industries Journal, 34(5–6), 2014, 399–421, where the relationship dialogue notion is discussed and ways of enhancing a dialogue in a professional service context are explored.

19. Ballantyne, D., Dialogue and its role in the development of relationship specific knowledge. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 19(2), 2004, 114–123.

20. Ballantyne, D. & Varey, R.J., Introducing a dialogical orientation to the service-dominant logic of marketing. In Lusch, R.F. & Vargo, S.L. (eds), The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing. Dialog, Debate, and Directions. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2006, pp. 224–235, p. 228.

21. Ballantyne & Varey, op. cit., p. 227.

22. Schein, E.H., The process of dialog: creating effective communication. The Systems Thinker, 5(5), 1994, 1–4 and Bohm, D., On Dialogue. London: Routledge, 1996.

23. Bohm, op. cit.

24. Dichter, E., How word of mouth advertising works. Harvard Business Review, 44(Nov–Dec), 1966, 147–166.

25. Peppers, D., Rogers, M. & Dorf, B., Is your company ready for one-to-one marketing? Harvard Business Review, 77(Jan–Feb), 1999, 151–160.

26. These word-of-mouth effects on ongoing relationships are discussed in Lindberg-Repo & Grönroos, op. cit.

27. Lindberg-Repo & Grönroos, op. cit. See also Lindberg-Repo, op. cit.

28. Lindberg-Repo, K., Customer Relationship Communication – Analysing Communication from a Value Generating Perspective. Helsinki, Finland: Hanken Swedish School of Economics, Finland, 2001. See also Lindberg-Repo, K. & Grönroos, C., Conceptualising communications strategy from a relational perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 33, 2004, 229–239.

29. Finne, Å. & Grönroos, C., op.cit., 180–181.

30. The temporal and situational factors influencing customers’ meaning creation are derived, respectively, from Mick & Buehl, op.cit. (meaning making is a function of internal and external factors influencing an individual’s perception of a communication message) and from Edvardsson, B. & Strandvik, T., Is a critical incident critical for a customer relationship? Managing Service Quality, 10(2), 2000, 82–91.

FURTHER READING

Arndt, J. (1969) Word of Mouth Advertising. New York: Advertising Research Foundation.

Ballantyne, D. (2004) Dialogue and its role in the development of relationship specific knowledge. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 19(2), 114–123.

Ballantyne, D. & Varey, R.J. (2006) Introducing a dialogical orientation to the service-dominant logic of marketing. In Lusch, R.F. & Vargo, S.L. (eds), The Service-Dominant Logic of Marketing. Dialog, Debate, and Directions. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, pp. 224–235.

Bateson, J.E.G. (1985) Perceived control and the service encounter. In Czepiel, J.A., Solomon, M.R. & Surprenant, C.E. (eds), The Service Encounter: Managing Employee/Service Interactions in Service Businesses. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, pp. 67–82.

Bohm, D. (1996) On Dialogue. London: Routledge.

Calonius, H. (1989) Market communication in service marketing. In Avlonitis, G.J., Papavasiliou, N.K. & Kouremeos, A.G. (eds), Marketing Thought and Practice in the 1990s. Proceedings from the XVIIIth Annual Conference of the European Marketing Academy, Athens, Greece.

Dichter, E. (1966) How word of mouth advertising works. Harvard Business Review, 44(Nov/Dec), 147–166.

Duncan, T. & Moriarty, S. (1997) Driving Brand Value. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Edvardsson, B. and Strandvik, T. (2000), Is a critical incident critical for a customer relationship? Managing Service Quality, 10(2), 82–91.

Evans, D. (2012) Social Media Marketing. An hour a Day. Indianapolis, IN: John Wiley & Sons.

Finne, Å. & Grönroos, C. (2009) Rethinking marketing communication: from integrated marketing communication to relationship communication. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(2–3), 179–195.

Fischer, A., Sieg, J.H., Wallin, M.W. & von Krogh, G. (2014) What motivates professional service firm employees to nurture client dialogues? The Service Industries Journal, 34(5–6), 399–421.

Grönroos, C. (1990) Service Management and Marketing. Managing the Moments of Truth in Service Competition. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Grönroos, C. & Lindberg-Repo, K. (1998) Integrated marketing communications: the communications aspect of relationship marketing. Integrated Marketing Communications Research Journal, 4(1), 3–11.

Grönroos, C. & Rubinstein, D. (1986) Totalkommunikation (Total communication). Stockholm, Sweden: Liber/Marketing Technique Centre. In Swedish.

Hui, M.K. & Bateson, J.E.G. (1991) Perceived control and the effects of crowding and consumer choice on the service experience. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(Sept), 174–184.

Keller, E. (2007) Unleashing the power of word of mouth: creating brand advocacy to drive growth. Journal of Advertising Research, December.

Kerr, G.F., Schultz, D., Patti, C. & Ilchul, K. (2008) An inside-out approach to integrated marketing communication: an international analysis. International Journal of Advertising, 27(4), 511–548.

Lindberg-Repo, K. (1999) Word-of-Mouth Communication in the Hospitality Industry. Helsinki/Helsingfors: Hanken Swedish School of Economics, Finland/CERS Centre for Relationship Marketing and Service Management.

Lindberg-Repo, K. (2001) Customer Relationship Communication – Analysing communication from a value generating perspective. Helsinki, Finland: Hanken Swedish School of Economics, Finland.

Lindberg-Repo, K. & Grönroos, C. (1999) Word-of-mouth referrals in the domain of relationship marketing. The Australasian Marketing Journal, 7(1), 109–117.

Lindberg-Repo, K. & Grönroos, C. (2004) Conceptualising communications strategy from a relational perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 33, 229–239.

Mick, D.G. & Buhl, C. (1991) A meaning-based model of advertising experiences. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(Dec), 317–338.

Mittal, B. (1999) The advertising of services. Meeting the challenge of intangibility. Journal of Service Research, 2(1), 98–116.

Mulhern, F. (2009) Integrated marketing communication: from media channels to digital connectivity. Journal of Marketing Communications, 15(2–3), 85–101.

Peppers, D., Rogers, M. & Dorf, B. (1999) Is your company ready for one-to-one marketing? Harvard Business Review, 77(Jan–Feb), 151–160.

Reichheld, F.F. (2003) The one number you need to grow. Harvard Business Review, 81(12), 46–55.

Schein, E.H. (1994) The process of dialogue: creating effective communication. The Systems Thinker, 5(5), 1–4.

Schultz, D.E., Tannenbaum, S.I. & Lauterborn, R.F. (1992) Integrated Marketing Communications. Lincolnwood, IL: NTC Publishing Group.