CHAPTER 15

MANAGING SERVICE CULTURE: THE INTERNAL SERVICE IMPERATIVE

“A functioning service culture requires that providing good service is second nature to everyone within the organization.”

INTRODUCTION

In this chapter the concept of service culture will be discussed. First, two broader concepts are presented, corporate culture and climate, and their importance to the attitudes and behaviour of people in an organization. Next, the issue of a service culture and the need for such a culture is covered. Prerequisites for a service culture are analysed and ways of creating such a culture are described. Finally, barriers to and opportunities for developing such a culture are discussed. After reading this chapter the reader should understand the importance of a service culture for service providers, know the prerequisites for a service culture and know how such a culture can be created.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CORPORATE CULTURE

The concept of corporate culture is used to describe a set of common norms and values shared by people in an organization. Hence, culture is an overall concept that explains why people do certain things, think in common ways, and appreciate similar goals, routines, even jokes, just because they are members of the same organization. Corporate culture can be defined as the pattern of shared values and beliefs that give the members of an organization meaning, and provide them with the rules for behaviour in the organization.1 Culture represents values that can be thought of as residing deep within the organization. It is not easy to see it, but it is always present.2 The existing culture in a firm is a result of its organizational past, and it provides stability, meaning and predictability in the organization.3

Corporate culture can be related to an internal climate in the organization. As discussed in the previous chapter, the organizational climate is partly dependent on how internal relationships function between people in the organization. The climate is the employees’ accumulated sense of what is important in an organization.4 Schneider, White and Paul describe service climate as a description of what happens in people’s work units with regards to the service-focused policies, practices, and procedures they experience, and to what they see is expected, supported and rewarded.5 The climate is a result of what goals employees are given to pursue in their jobs and how daily routines are handled in the organization.6 The climate has a direct external effect on customer experiences and on perceived service quality, and may also influence customer loyalty.7

Service providers have to manage their internal climate so that employees who serve internal or external customers develop positive attitudes towards providing service. Such attitudes and a service-oriented climate can be expected to exist if the employees feel that organizational routines, directions for action given by policies and management and reward systems indicate that focusing on giving good service is important.8 Because of this, the culture and climate of a firm have a vital impact on how service-oriented its employees are.9 The terms culture and climate are often used interchangeably to mean more or less the same thing, because they are so closely related to each other.10

Culture is an important phenomenon to study and understand, because it is considered a potential basis for competitive advantage.11 For service firms and manufacturers facing service competition, the development and management of a service culture is a critical task.

Internal activities or projects, such as training programmes, do not lead to expected results if they do not fit the existing culture in the firm. For example, a service-oriented training programme alone would probably have no significant impact on the thinking and behaviour of employees of a manufacturer where goods-oriented industrial norms are highly regarded, or the employees of a service firm where sales and cost-efficient operations are the only visible management priorities.12 A much more strategically-oriented and comprehensive process would be needed if any results are to be achieved (see Chapter 14).

A weak corporate culture, where there are few or no clear common shared values, creates an insecure feeling concerning how to respond to various clues and how to react in different situations. For example, when a company has a strong culture, what to do when a customer has unexpected requests may be self-evident. On the other hand, if there is a weak culture, such a situation frequently results in inflexible behaviour by contact employees, long waiting times and a feeling of insecurity on the part of the customer. This, of course, hurts customer perceived service quality. In such a culture, employees do not have any clear norms to which to relate, for example, sales training or service skills courses, and hence they do not know how to respond to such activities.

A strong culture, however, enables people to act in a certain manner and to respond to various actions in a consistent way.13 Clear cultural values seem particularly important for guiding employee behaviour, especially in service organizations.14 In many cases new employees are easily assimilated into the prevailing culture.15 A customer-focused and service-minded person with a favourable part-time marketing attitude who is recruited for a service job may quickly be brought down to earth by his new colleagues who share strong values which do not honour interest in customers or in providing good service. On the other hand, a strong service-oriented culture easily snowballs. Service-oriented employees are attracted by such an employer, and most new employees are influenced in a favourable way by the existing service culture.

When employees identify with the values of an organization, they are less inclined to quit, and customers seem to be more satisfied with the service provided. In addition to this, when there is a minimal employee turnover, service-oriented values and a positive attitude towards service are more easily transmitted to newcomers in the organization.16

The modern views of quality and productivity are related to corporate culture. Improving productivity and quality requires a new way of thinking in the culture of the organization.

A strong culture is not, however, always good. In situations where the surrounding world has changed and new ways of thinking are called for, a dominating culture may become a serious hindrance to change. It may be difficult to respond to new challenges. In such a situation, a strong culture does not only affect the responsiveness of employees in a negative fashion, but may also paralyse management. For example, a strong manufacturing-oriented or sales-focused culture may develop into a serious obstacle for a firm that should obviously respond to service-related changes in the market, or to a situation where keeping existing customers has become the most important way of doing profitable business. A service strategy is perhaps the obvious solution, but the management team may be too restricted by their inherited way of viewing the business. If only marginal internal activities to introduce a service strategy are implemented, old-fashioned ways of thinking among middle management and the rest of the personnel do not permit any major attitude change.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CLIMATE AND CULTURE IN SERVICE ORGANIZATIONS

In a service context a strong and well-established culture, which enhances an appreciation for good service and customer orientation, is extremely important. This follows from the nature of service production and consumption. Normally, service production cannot be standardized as completely as an assembly line, because of the human impact in the buyer–seller interactions of the service encounters. Customers and their behaviour cannot be totally standardized and predetermined. Situations vary, and therefore a distinct service-oriented culture is needed which tells employees how to respond to new, unforeseen and even awkward situations.17 Hence, the culture makes a service-oriented strategy come alive for the employees and directs their behaviour.18 In conclusion, it will be difficult to implement a service strategy without the existence of a service-focused culture in the organization.

It has been argued that a strong culture is of vital important in service organizations, because the attitude and performance of the employees is so visible to customers. If employees experience a service-oriented climate, the customers’ experience of service quality will probably be better than otherwise expected. There seems to be a clear interrelationship between employee experiences and customer experiences.19

Since service quality is a function of the co-operation of so many resources – human as well as technological – a strong culture that enhances quality is a must for successful management of quality in a service context. Moreover, since it is more difficult to control quality in a service context than in manufacturing, service-oriented and quality-conscious values are necessary in the organization. In this way management can execute indirect control by culture.20

MANAGING RELATIONSHIPS REQUIRES A SERVICE CULTURE

Managing customer relationships demands that the firm adopt a service perspective, and customer relationships (as well as relationships with suppliers, distributors and other types of network partners) include a large number of service activities. Some of them, such as over-the-counter personal service, goods deliveries, maintenance and consulting services, can easily be seen by management as what they are in the minds of customers, that is, as value-creating services. Other types of services, such as invoicing, complaints handling, answering phone calls or e-mails, and a host of similar activities, which were earlier labelled hidden, unbillable services in relationships, are not as easily recognized as value-supporting services.

If the culture in a firm which has decided to give priority to the management of customer relationships (and relationships with other parties) does not honour service and a constant attention to providing good service to the other party, it will be difficult to implement the relationship-oriented strategy. The non-service culture will keep people (managers, supervisors and customer contact employees alike) from realizing the importance of all the ‘hidden services’, and even the more visible service elements may not be given enough attention. The values that dominate in the firm will direct people’s attention elsewhere. Therefore, managing customer relationships, and relationships with other parties, requires a service-oriented culture.

PROFITABILITY THROUGH A SERVICE STRATEGY REQUIRES A SERVICE CULTURE

Adopting a service logic and a service perspective and implementing a service strategy requires the support of all employees in the organization. Top management, middle management, customer contact employees and support employees will all have to get involved and perform according to such a strategy. An interest in service and an appreciation of good service among managers and all other employees is an essential requirement. What is needed is a corporate culture that can be labelled a service culture. Such a culture can be described as:

. . . a culture where an appreciation for good service exists, and where giving good service to internal as well as ultimate, external customers is considered by everyone a natural way of life and one of the most important values.21

Hence, service has to be the raison d’être for all organizational activities.22 This, of course, does not exclude other values from being important, too. For example, attention to internal efficiency and cost control is still important, as well as an appreciation of sales and getting new customers. However, the service-oriented values should have a dominating position in the organization with a top-priority concern in strategic as well as operational thinking and performance, and not remain a marginal or lower-priority concern.

In a service culture all employees should be service-focused. Service orientation can be described as shared values and attitudes that influence people in an organization so that interactions between them internally and interactions with customers and other external actors are perceived in a favourable manner. Internally, a service focus can be expected to enhance the internal climate and improve the quality of internal service and support. Externally, a service focus should create good perceived quality for customers and others as well as lead to strengthened relationships with customers and other parties.

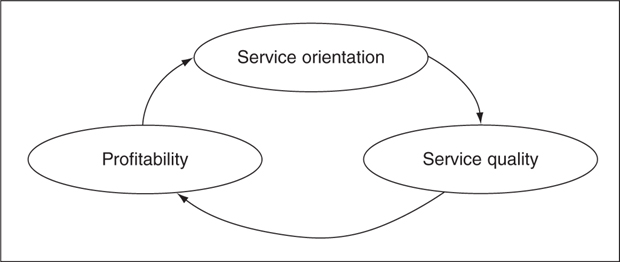

Clearly, a service orientation enhances the functional quality dimension of customer perceived service quality, and probably also supports good technical quality. As Figure 15.1 illustrates, service orientation among personnel normally fuels an important positive process within an organization. A service orientation that is a characteristic of a service culture improves service quality as perceived by customers.

Service-focused employees who take an interest in their customers do more for the customers, are more courteous and flexible, try to find appropriate solutions to customers’ wishes, and go out of their way to recover a situation where something has gone wrong or an unexpected scenario has occurred. Furthermore, we know that customer perceived quality is a key determinant of profitability, although it is not the only one. Hence, service orientation improves service quality which, in turn, positively affects profitability. This favourable process continues as an upward spiral, because better profitability provides means to maintain and further improve service-oriented attitudes among personnel. The process fuels itself.23

FIGURE 15.1

Effects of a service orientation.

A word of warning is important here, however. Although good perceived quality can be expected to improve profitability, this requires that the service offerings provided to customers are put together in such a way that customers are prepared to pay a price which matches the cost of producing the service. There are situations where customers may be very satisfied with the perceived service quality, but they are still not profitable over time.24 Furthermore, the positive connection between culture and profitability is often claimed to exist, and a clear service-oriented culture probably has a favourable impact on the financial performance of the firm. In Chapter 6, and especially in Figure 6.9, factors that influence the link from perceived quality to profitable customers were discussed. It is difficult to show how a service culture and service orientation leads to profitable customer relationships, because there are always so many external factors involved that it is difficult to isolate the effects of culture.25

SHARED VALUES

The values shared by people in an organization and the prevailing norms are the foundation of the culture. The shared values constitute guidelines for employees in performing their everyday tasks. In an organization with strong shared values three common characteristics are often present:26

The shared values are a clear guideline for task performance.

Managers devote much of their time to developing and reinforcing the shared values.

The shared values are deeply anchored among the employees.

Performance is improved by strong shared values in an organization. Managers and employees devote themselves more to issues and ways of performing that are emphasized by the shared values. Performance is better, because people are more motivated. Strong shared values may, however, become a problem, too; for the following reasons:

• The shared values may have become obsolete and are therefore not consistent with current strategies and service concepts.

• Strong shared values may lead to resistance to change, which makes it difficult for the organization to respond to external challenges.

• New employees are formed by existing strong shared values, and in situations when the culture needs to be changed, differently thinking newcomers are easily swallowed by the existing culture.

In many firms these are highly relevant problems. Even though there may be no service culture, there may still be a strong corporate culture. The existing culture may emphasize manufacturing ideals or bureaucratic routines, or press short-term sales instead of the importance of concentrating on keeping and growing customers. In many manufacturing firms and institutions within the public sector, a strong culture that does not appreciate service is a major hindrance to change. Challenges from the market and from society may go unnoticed, or the organization may not be capable of adjusting to the need for change. The results are sometimes fatal. The effects of a single internal activity, for example a training programme that does not have a strategic foundation, will probably be counteracted by a hostile culture. Internal marketing efforts may easily fail if they are not in line with the prevailing culture, or if the objectives of the internal marketing efforts are contradictory to it. On the other hand, a long-term internal marketing process is one ingredient in a process that aims at changing an existing culture. A strategic approach to internal change is needed.

REQUIREMENTS FOR A SERVICE CULTURE

Introducing and implementing a service strategy requires a service culture. In many firms and in many organizations within the public sector, a cultural change is called for. Such a change is a long-range process, which demands extensive and long-range activity programmes. In the previous chapter we discussed one major ingredient in such a process, internal marketing. This chapter will look at general prerequisites for achieving a service culture.

The requirements for good service27 are strategic requirements, organizational requirements, management requirements, and knowledge and attitude requirements.

If all four kinds of requirements are not all recognized, the internal change process will suffer and the result will be mediocre at best. The four different requirements above are intertwined. For example, a complicated organizational structure may make it impossible to implement a good service concept; or a service-minded, customer-focused and motivated contact employee becomes frustrated and loses interest in providing good service because he gets no support or appreciation from his boss, or finds it impossible to be service-minded because the service orientation is not derived from a strategic foundation, and therefore sufficient resources are not granted and continuous and consistent top management support is lacking. The following sections will discuss the four requirements above in some detail.

DEVELOPING A SERVICE STRATEGY

The strategic requirements for good service are fulfilled by developing a service-focused strategy. This means that top management wants to create a service-focused organisation; the management team is not just paying lip service to service orientation. Here, top management may be the CEO or the managing director and his management team, but it may also be the head of a regional or local organization or a profit centre, which can operate sufficiently well independently.

The business mission is the foundation of strategy formulation. Strategies are developed based on the scope and direction of the business indicated by the mission. A service strategy means that the mission includes a service vision. It demands that a service orientation, which of course means different things in different industries and even firms, is to be achieved. This will not be discussed here. In Chapter 3 guidelines for formulating a service-based and customer-focused business mission were presented. In short, in a generic way the business mission of a service-focused firm that has adopted a service perspective for its business can be described in the following way:

The business mission is to provide the customers’ activities and processes with support that makes value for the customers emerge when they do those activities and run those processes.

This support could, of course, be of any kind, including goods, services, hidden services, or information, as long as when the customers make use of it, value emerges for them. For business customers this value support should ultimately have a favourable effect on the customers’ business process and even on the customers’ customers’ processes. Although similar effects on individual customers are less obvious and more difficult to measure, in principle the support of a service provider should lead to similar effects.

However, a service strategy requires that service concepts related to the business mission and the strategy be defined. If service concepts are not clearly defined, the firm lacks a stable foundation for discussion of goals, resources to be used, and performance standards. As previously stated, the service concept states what should be done, to whom, how and with which resources, and what benefits customers should be offered. If these issues are not clarified, personnel will not understand what they are supposed to do. Moreover, goals and routines do not form a clear and understandable pattern, because there is no clear and well-known service concept to relate them to. If the service concepts are not clearly understood at the middle management level, it will be difficult to perform supervisory duties consistently.

Human resource management is an important part of strategic requirements. Recruitment procedures, career planning, reward systems and so on are vital parts of a service culture. Good service performance has to guide HRM. The more aspects other than skills and service-orientation dominate, for example recruitment procedures and reward systems, the less inclined towards service-mindedness employees will be, and a service culture will be difficult to achieve.

Good service has to be rewarded and accomplishments have to be measured in such a way that employees realise the importance of service. However, able employees are sometimes forced to do dumb things, because measurement and reward systems are wrong. Quite often only internal efficiency issues, such as the number of meals served in a restaurant or the number of phone calls dealt with, are measured and reward systems developed accordingly. If this is the case, and employees feel they are rewarded for accomplishments other than excellent service quality, any attempt to develop a service culture is bound to fail.

DEVELOPING THE ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

Development of the organizational structure creates the organizational prerequisite for good service. All aspects of organization design have to be geared to the service process, if high service quality is to be achieved and consistently maintained. The more complicated the formal structure is, the more problems related to giving good service will occur. The organization of a firm can be a serious obstacle to a service culture. Good service means, among other things, easy access to service and quick and flexible decision-making. It requires co-operation between various departments in designing, developing and executing service. If the organizational structure does not allow employees to perform in this way, values characterizing a service culture cannot be developed. Good intentions, even when they are based on strategy, cannot be implemented without the structure being in place. This makes people frustrated and may have a counter-effect. Employees may feel that management demands the impossible, and this only achieves negative effects as far as service-oriented attitudes are concerned.

There is also an informal organizational structure. People create a value structure and personal contacts, which make the formal structure either less or more complicated. In the former case, positive attitudes among the employees involved may make it possible to solve the problems created by a complicated structure. In the latter case, on the other hand, even a service-oriented structure may be an obstacle to good service. If people do not want to collaborate, a service culture is harder to accomplish.

Normally, a service-oriented firm requires a relatively flat organizational structure with few hierarchical levels. Decisions have to be made by employees who are close to the customers. The roles of managers change. The customer contact and support employees have more responsibility and they are expected to perform more independently. However, this does not mean that the supervisory level loses power, only that the role of supervisors changes. They are not just technical managers and decision-makers any more; instead, they are supposed to be coaches and demonstrate leadership. They will have to assist and encourage their staff and create an open climate where good service is a leading shared value.

The role of supervisors in support functions must also be clarified. Often employees who do not have immediate customer contacts regard themselves as carrying out passive functions with some administrative duties. In fact, their role in most support functions is much more active. As we have noted in previous contexts, they should see people in customer contact functions as their internal customers, whom they will have to serve as well as they, in turn, serve the ultimate (external) customers.

In many firms, the customer contact functions are understaffed, whereas back office and staff functions departments are overstaffed. The obvious conclusion is to strengthen the customer contact processes and streamline and redesign other departments so that they support the buyer–seller interactions in a more effective and service-focused way.

Another aspect of organizational development is the creation and improvement of operational systems, routines and work flows. Good service normally requires simplified ways of doing things, so that unnecessary delays and information breakdown are avoided. The effects of this are twofold. First of all, customers perceive such a development as better functional quality of the service. Second, employees feel that their job has become more meaningful and motivating when routines and work flows have been simplified, and unnecessary or time-consuming elements of the operational systems have been eliminated.

Information technology also provides opportunities to make changes in internal information systems and operational systems. The introduction of intranets can create a feeling of belonging and strengthen corporate identity among personnel. An intranet makes everyone a member of the same information system and makes it possible, for example, for every customer contact and support employee to share the same, relevant information about a given customer at the same time. If the information is easily retrievable, constantly updated and relevant, such a system supports good and timely interactions with customers and helps employees to give good service. This can contribute to a positive service culture. On the other hand, when using intranets in this way there is a danger of information overload, which must be monitored. Such overload easily counteracts the maintenance of a service culture.

DEVELOPING LEADERSHIP

The management prerequisite for good service is promoted by establishing a service-oriented leadership.28 This includes managers’ and supervisors’ attitudes towards their role, their teams and how they act as managers. Management must be supportive, inspirational and attuned to the individuals they manage. Without active and continuous support from all managers and supervisors, the values that characterize a true service culture cannot be spread throughout the organization and maintained once they have been established. Such a managerial impact is of vital importance if service-oriented values are to be communicated to the employees, strengthened and made an integral part of the everyday life of the organization.

Managers are leaders in an organization, and by leading they also contribute to the culture. In this way managers, and supervisors, have a key role in the development of a service culture. On the other hand, a manager who is not aware of this will be led by the culture.29 This can be a problem in a situation when the culture needs to be changed. Hence, it is very important for every manager and supervisor in the organization to be aware of the corporate culture.

Simply being a technical manager without taking on the role of coach and leader does not do much for the pursuit of a service culture. A more whole-hearted devotion to the service concepts and the employees is called for. Service is still to a large extent a human business and the result of interactions between people internally as well as externally. Management styles that do not take this into account do not fit in here.

Communication is a critical ingredient of leadership. The manager and supervisor will have to be willing, and know how to communicate with their staff. Communication is a two-way street, where the ability to listen to others is an important component. A leader should be able to create a dialogue with his team, and also be able to give clear direction and guidance, and make decisions when he is expected to take a firm stand.

One of the biggest risks involved in a process towards a service orientation is the risk of ambiguity. If the manager talks about the need for service-mindedness and customer-consciousness, but in reality does not pursue a service strategy, he and the service culture lose credibility. A sense of uncertainty among personnel is easily created, and the idea of service orientation and a service culture will not be taken seriously any more. Performance that is in line with good quality and the nature of a service culture as expressed by management has to be measured and rewarded. Internal efficiency and manufacturing-oriented productivity measures must not be given priority. Hence, management has to talk about the importance of good service and of pursuing a service culture, and demonstrate by their actions their belief in this idea. Otherwise, serious damage may easily be done to a service-orientation process that may have been initiated in good faith.

The top person in the organization, which may be a firm, a local unit, a profit centre, a strategic business unit or another well-defined organizational unit, will constantly have to give the service strategy top priority, and continuously and actively give it his strong support. Furthermore, every manager and supervisor will have to accept the role of a coach. They have to be able to encourage employees and strengthen their motivation for service-oriented performance.

Monitoring performance and results is, of course, still an integral part of management. But the traditional role of management is shifting from controlling towards guiding employees. Many managers feel that their authority is eroding as a consequence of such a change, and they cannot effectively ‘manage’ their people any more. However, this is not the case. The leadership-oriented management philosophy does not mean that management abdicates, but instead that it sets up goals and guidelines and delegates operational responsibility in a clear manner. Hence, the traditional role as mere technical manager is changed to a new role characterized by leadership and coaching. Another aspect of a service-oriented management style is the development of an open internal communication climate. On the one hand, employees need information from management to be able to implement a service strategy; on the other hand, they have valuable information for management about customers’ needs and wishes, about problems and opportunities, and so on. Feedback is required so that they see the results of their job and their actions, otherwise employees easily lose interest in what they are doing.

It is a good idea to get contact employees involved in the planning process and in decision-making concerning, say, what new services to offer and how they should be produced. Overall objectives for a group or a department can be broken down into sub-goals for that unit in co-operation with the employees who are supposed to accomplish those goals. This process is, first, a way of communicating the strategy and objectives of the firm to the employees, and second, a way of achieving employee commitment to the service strategy and to the firm’s goals.

Finally, as noted in the previous chapter, management methods and the attitudes of managers and supervisors towards their employees are of pivotal importance to the long-term success of an internal marketing process.

Schneider and White summarize the impact of leadership in the following way.30 The role of the leader is to:

• Espouse service-focus values among the employees.

• Develop policies, practices and routines that are consistent with these values.

• Ensure that those who most fully implement these procedures, to achieve a service-focused climate, are recognized for this and rewarded.

SERVICE TRAINING PROGRAMMES

By training employees, the knowledge and attitude requirements for good service can be achieved. However, to be effective training must be supported by the three other prerequisites for a service culture. Training employees is also an integral part of internal marketing. In organizations where existing values are not service-oriented, an attitude of resistance to change can be expected. A large portion of this resistance can be removed by creating the previously discussed strategic, organizational and management prerequisites for good service. However, this resistance is also a question of attitude and a lack of knowledge and skills. If the three requirements discussed above are not attended to, negative attitudes easily prevail or develop among the personnel. If the firm has always operated in, say, a manufacturer-oriented or bureaucratic way, it is not easy to make people think in new directions. This goes for management as well as for other employees.

If top management, middle management, and support and customer contact employees are expected to be motivated for service-oriented thinking and behaviour, they will need to know how a service organization operates, what makes up customer relationships, what their role in the operation and in customer relationships is, and what is expected of the individual. A person who does not understand what is going on and why cannot be expected to be motivated to do a good job as a contact person or an internal service provider in support functions behind the line of customer visibility.31

Moreover, every person should be aware of the firm’s business mission, strategies and overall objectives as well as the goals of his own department and function, and his own personal goals. Otherwise, it would be unrealistic to think that an employee understands why he is told that it is important to perform in a certain way. This is even more crucial for employees in support functions than for contact employees.

In training programmes, knowledge-oriented training and attitude training are intertwined. The more knowledgeable a person is, the easier it is for that person to have positive attitudes towards a specific subject. It is essential to realise that attitudes can seldom be changed without knowledge. Pep talks may help on some occasions, but if people do not have the facts they will never create enduring service-focused attitudes. Employees need to know why the firm is a service business, or why as a manufacturer it adopts a service strategy; which requirements for performance follow from this; what their role is in relation to other functions and people, and in relation to customers; what is demanded of them as an individual, and why. And if a person feels that he does not have the required skills, he will also be reluctant to change.

Service training can be divided into three categories:

Developing a holistic view of the firm and its sub-functions as a service organization and how it operates in a market-oriented manner.

Developing skills concerning how various tasks are to be performed.

Developing specific communication and service skills.

All three types of training are needed. The first type gives a general foundation for understanding a service strategy and how to implement it. It puts every function, department and task into perspective, and demonstrates how the processes in the organization and the people performing these processes are related to each other and to a common goal of servicing customers well and creating support for their value-creating processes. The second type, vocational training, provides the skills required so that employees can perform their tasks, which may have been changed after the introduction of a service strategy, in an efficient way. The third type of training provides employees, especially customer contact employees but also support employees, with specific skills as far as communication and interaction tasks are concerned. Courses that address service-mindedness belong to this group, too. A serious mistake, which is all too common, is to believe that only the third type of training is needed to change employee attitudes. Such an approach is hardly ever successful.

DEVELOPING A SERVICE CULTURE: BARRIERS AND OPPORTUNITIES

Clearly, the task of changing the corporate culture and creating a service culture is a huge one. And it will take a substantial amount of time until any results will be observable. Getting started is often a substantial problem. There is an initial barrier to starting the process, and there is a threshold to cross on the way. Before this happens, no major changes can be seen in the internal value systems. However, once the process develops far enough it usually gains pace, provided it is constantly supported and enhanced, especially by top management. A service culture has to be maintained once it has been achieved, otherwise there is always the risk that the interest in service and in servicing internal as well as external customers will start to deteriorate.

In some situations it is easier to get started than in others. Favourable conditions for a change process are:

• Environmental pressure, such as increased competition, changes in customer needs and expectations, the introduction of new technologies, or deregulation or regulation of the industry.

• New organizational strategies, which differ from the previous ones.

• New structural arrangements, such as new management or a major change in the organizational structure.

All or some of these things could, of course, occur simultaneously, which would probably help the process. When times are good, and problems seem to be too far into the future or are invisible to most people in the organization, it is much more difficult to start to change the existing corporate culture. However, when altering an organization’s culture, it is critical to preserve some of what has gone before and build on it to make the change. Honouring and learning from the past is important and does not have to mean that it slows down the process or counteracts it.32 It is probably a good idea to move slowly, to set intermediate goals and to make changes gradually. Sometimes, however, there is no time for that. In most cases there is though, and trying to implement change too rapidly may lead to bad results. A cultural change means that the mindset of people has to change. The process has to be planned and executed in the same way as any important organizational task.

NOTES

1. Davis, S.M., Managing Corporate Culture. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger, 1985. This somewhat dated definition by Davis still very accurately describes the concept of corporate culture. See also, for example, Iglesias, O., Montana, J. & Sauguet, A., The role of corporate culture in relationship marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 45(4), 2011, 631–650.

2. Bowen, D.A., Schneider, B. & Kim, S.S., Shaping service cultures through strategic human resource management. In Swartz, T.A. & Iacobucci, D. (eds), Handbook of Services Marketing & Management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2000, pp. 439–454. See also Shein, E.H., Corporate Culture. In Vogelsang, J. et al. (eds.), Handbook for Strategic HR. Chicago, IL: AMACOM, 2013, pp. 252–258.

3. Schein, E.H., Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1992.

4. Schneider, B. & Bowen, D.E., Winning the Service Game. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1995.

5. Schneider, B., White, S.S. & Paul, M.C., Linking service climate and customers perception of service quality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 1998, 150–163.

6. Schneider, B., Brief, A.B. & Guzzo, R.A., Creating a climate and culture for sustainable organizational change. Organizational Dynamics, 24(4), 1996, 7–19.

7. Bowen, D.E. & Schneider, B., A service climate synthesis and future research agenda. Journal of Service Research, 17(1), 2014, 6, 10–11.

8. Schneider, B., The climate for service: an application of the climate construct. In Schneider, B. (ed.), Organizational Climate and Culture. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1990, pp. 383–412.

9. See also Edvardson, B. & Enquist, B., Quality improvement in governmental services: the role of change pressure by the ‘market’. The TQM Magazine, 18(1), 2006, 7–21, where the authors study the situation in a public sector context.

10. See Bowen, D.E. & Schneider, B., op. cit., where a distinction between service climate and other concepts such as service orientation is made.

11. Barney, J., Organizational culture. Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 1986, 656–666. See also Flamholtz, E.G. & Randle, Y., Corporate culture, business models, competitive advantage, strategic assets and the bottom line: theoretical and measurement issues. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 16(2), 2012, 76–94, where the relationship between corporate culture and the competitive advantage of a firm is discussed, and Guiso, L., Sapienza, P. & Zingales, L., The value of corporate culture, Journal of Financial Economics, [online, 24 May 2014] where it is shown that the relationship between corporate culture and firm performance may not be straightforward.

12. See Skålen, P. & Strandvik, T., From prescription to description: a critique and reorientation of service culture. Managing Service Quality, 15(3), 2005, 230–244, where the authors study the effects of a service management programme in a public sector situation. Because the goals of the programme and the existing culture were far apart, the programme created more confusion in the organization than helped, changing the culture into a service-oriented direction.

13. Brown, S.W., The employee experience. Marketing Management, 12(2), 2003, 12–16.

14. Schneider, B., Notes on climate and culture. In Venkatesan, M., Schmalensee, D.M. & Marshall, C. (eds), Creativity in Services Marketing. What’s New, What Works, What’s Developing. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association, 1986.

15. Schein, op. cit.

16. Bowen, D.E. & Schneider, B., Service marketing and management: implications for organizational behavior. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10, 1988.

17. Schneider, op. cit.

18. See Schneider, B., Hayes, S.C., Lim, B.-C. & Raver, J.L., The human side of strategy: employee experiences of strategic alignment in a service organization. Organizational Dynamics, 32(2), 2003, 122–138.

19. Schneider, B., White, S. & Paul, M.C., op. cit.

20. Brown, 2003, op. cit. And for example, in a study of the airline industry it became clear that the service culture had a direct effect on service behaviour. See Zerbe, W.J., Dobni, D. & Harel, G.H., Promoting employee service behaviour: the role of perceptions of human resource management practices and service culture. Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 15(2), 1998, 165–179.

21. Grönroos, C., Service Management and Marketing. Managing the Moments of Truth in Service Competition. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1990, p. 244. See also, for example, Beitelspacher, L.S., Richey, R.G. & Reynolds, K.E., Exploring a new perspective on service efficiency: service culture in retail organizations. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(3), 2011, 215–228.

22. To use the words of Schneider and Rentsch, service has to become ‘the raison d’être for all organizational activities’ and an ‘organizational imperative’. See Schneider, B. & Rentsch, J., The management of climate and culture. In Hage, J. (ed.), Futures of Organizations. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1987.

23. See Gebauer, H., Edvardsson, B. & Bjurko, M., The impact of service orientation in corporate culture on business performance in manufacturing companies. Journal of Service Management, 21(2), 2010, 237–259, where this relationship is discussed in a manufacturing context.

24. In a large study of the profitability of customer bases in retail banks in Scandinavia, Kaj Storbacka showed that a large number of satisfied customers had a substantial negative effect on the overall profitability of the bank. See Storbacka, K., The Nature of Customer Relationship Profitability. Helsingfors, Finland: Swedish School of Economics, Finland/CERS, 1994.

25. Bowen, Schneider & Kim, op. cit. See also Siehl, C. & Martin, J., Organization culture: a key to financial performance? In Schneider, B. (ed.), Organizational Climate and Culture. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1990, pp. 241–281. See also Edvardsson, B. & Enqvist, B., The IKEA saga: how service culture drives service strategy. The Service Industries Journal, 22(4), 2002, 153–166.

26. Deal, T.F. & Kennedy, A.A., Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1982.

27. Grönroos, C., 1990, op. cit.

28. See Schneider, B. & White, S.S., Service Quality. Research Perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004.

29. Schein, op. cit.

30. Schneider & White, op. cit., p. 118.

31. Jan Carlzon, the former managing director and president of SAS, illustrates in his book about the turnaround process of SAS in the 1980s (Moments of Truth. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger, 1987) the impact of a holistic understanding of the tasks people are involved in by the following anecdote:

There is no better way to sum up my experience than with the story about the two stone cutters who were chipping square blocks out of granite. A visitor to the quarry asked what they were doing. The first stone cutter, looking rather sour, grumbled, ‘I’m cutting this damned stone into a block.’ The second, who looked pleased with his work, replied proudly, ‘I’m on this team that’s building a cathedral.’

This anecdote is still often told in similar contexts. It is interesting to note that, in slightly different words, Mikhael Gorbachev, former leader of the Soviet Union, told it as an illustration of the perestroika process. See Gorbachev, M., Perestroika – New Thinking for Our Country and the World. New York: Harper & Row, 1987.

32. Zemke, R., Creating service culture. The Service Edge, 8, 1988.

FURTHER READING

Barney, J. (1986) Organizational culture: can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 656–666.

Beitelspacher, L.S., Richey, R.G. & Reynolds, K.E. (2011) Exploring a new perspective on service efficiency: service culture in retail organizations. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(3), 215–228.

Bowen, D.E. & Schneider, B. (1988) Service marketing and management: implications for organizational behavior. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10.

Bowen, D.E. & Schneider, B. (2014) A service climate synthesis and future research agenda. Journal of Service Research, 17(1), 5–22.

Bowen, D.A., Schneider, B. & Kim, S.S. (2000) Shaping service cultures through strategic human resource management. In Swartz, T.A. & Iacobucci, D. (eds), Handbook of Services Marketing & Management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, pp. 439–454.

Brown, S.W. (2003) The employee experience. Marketing Management, 12(2), 12–16.

Carlzon, J. (1987) Moments of Truth. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

Davis, S.M. (1985) Managing Corporate Culture. Cambridge, MA: Ballinger.

Deal, T.F. & Kennedy, A.A. (1982) Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Edvardsson, B. & Enqvist, B. (2002) The IKEA saga: how service culture drives service strategy. The Service Industries Journal, 22(4), 153–166.

Edvardson, B. & Enquist, B. (2006) Quality improvement in governmental services: the role of change pressure by the ‘market’. The TQM Magazine, 18(1), 7–21.

Flamholtz, E.G. & Randle, Y. (2012) Corporate culture, business models, competitive advantage, strategic assets and the bottom line: theoretical and measurement issues. Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, 16(2), 76–94.

Gebauer, H., Edvardsson, B & Bjurko, M. (2010) The impact of service orientation in corporate culture on business performance in manufacturing companies. Journal of Service Management, 21(2), 237–259.

Gorbachev, M. (1987) Perestroika – New Thinking for Our Country and the World. New York: Harper & Row.

Grönroos, C. (1990) Service Management and Marketing. Managing the Moments of Truth in Service Competition. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P. & Zingales, L. (online 2014) The value of corporate culture. Journal of Financial Economics.

Iglesias, O., Montana, J. & Sauguet, A. (2011) The role of corporate culture in relationship marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 45(4), 631–650.

Schein, E.H. (1992) Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schein, E.H. (2013) Corporate Culture. In Vogelsang, J. et al. (eds.), Handbook for Strategic HR. NY: AMACOM, pp. 252–258.

Schneider, B. (1986) Notes on climate and culture. In Venkatesan, M., Schmalensee, D.M. & Marshall, C. (eds), Creativity in Services Marketing. What’s New, What Works, What’s Developing. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association.

Schneider, B. (1990) The climate for service: an application of the climate construct. In Schneider, B. (ed.), Organizational Climate and Culture. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, pp. 383–412.

Schneider, B. & Bowen, D.E. (1995) Winning the Service Game. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Schneider, B. & Rentsch, J. (1987) The management of climate and culture. In Hage, J. (ed.), Futures of Organizations, Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Schneider, B., Brief, A.B. & Guzzo, R.A. (1996) Creating a climate and culture for sustainable organizational change. Organizational Dynamics, 24(4), 7–19.

Schneider, B., White, S. & Paul, M.C. (1998) Linking service climate and customer perception of service quality: test of a causal model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 150–163.

Schneider, B., Hayes, S.C., Lim, B.-C. & Raver, J.L. (2003) The human side of strategy: employee experiences of strategic alignment in a service organization. Organizational Dynamics, 32(2), 122–138.

Schneider, B. & White, S.S. (2004) Service Quality. Research Perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Siehl, C. & Martin, J. (1990) Organization culture: a key to financial performance? In Schneider, B. (ed.), Organizational Climate and Culture. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, pp. 241–281.

Skålen, P. & Strandvik, T. (2005) From prescription to description: a critique and reorientation of service culture. Managing Service Quality, 15(3), 230–244.

Storbacka, K. (1994) The Nature of Customer Relationship Profitability. Helsingfors, Swedish School of Economics, Finland/CERS Centre for Relationship and Service Management.

Zemke, R. (1988) Creating service culture. The Service Edge, 8.

Zerbe, W.J., Dobni, D. & Harel, G.H. (1998) Promoting employee service behaviour: the role of perceptions of human resource management practices and service culture. Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 15(2), 165–179.