Chapter 4

Expressive Influence

Sending Ideas and Generating Energy

Nothing great was ever accomplished without enthusiasm.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

The Purpose of Expressive Influence

Expressive influence sends your ideas and energy out to others. Many people think of influence as primarily an expressive activity—one in which they're continually sending ideas and information toward others. In fact, effective influence requires a balance of expressive and receptive activity, as does any form of communication.

Too many people overuse or misuse expressive influence. On the one hand, you've probably been in meetings where long-windedness, repetitiveness, a sleep-inducing slide presentation, and/or an excruciating level of detail caused you to leave the meeting mentally or physically without absorbing or being influenced by a single idea. There was probably little or no opportunity to ask a question or make a comment that might have sparked a productive discussion. Virtual attendees were ignored. Often, the speaker involved in such a meeting is unaware of his or her impact (or lack of it) because he or she is focused internally on what to say next, rather than attending to whether or not the current words are having an impact.

On the other hand, you may have had the good fortune to listen to someone who stimulated your thinking with an exciting idea, changed your mind through an excellent argument, made you an offer you didn't want to refuse, or inspired you to believe that you could accomplish great things.

Expressive influence, used effectively, can lead people to action. It's especially effective when people are uncertain about what to do and have respect for and trust in the person who is influencing. The use of expressive influence can communicate to others that you mean business and are to be taken seriously. It allows you to communicate your enthusiasm for an idea or belief and exhort others to share it.

The Expressive Behaviors

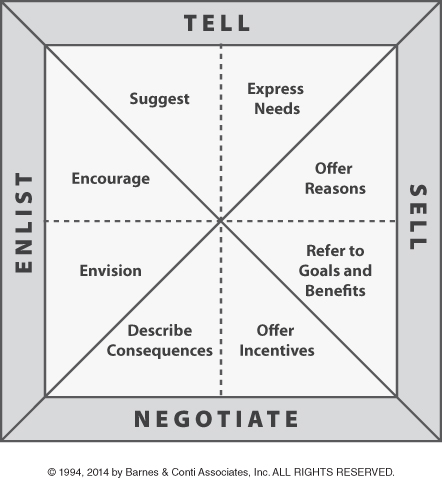

Figure 4.1 shows the specific tactics and behaviors associated with expressive influence. The expressive tactics in this model are named according to what they are intended to do. They include Tell, Sell, Negotiate, and Enlist.

Figure 4.1 Expressive Influence Tactics and Behaviors.

- You can Tell by making a suggestion or by expressing your needs.

- “Let's meet twice a month on the standards issue until we're ready to present the report.” (Suggest)

- “I need your input on the plans by Friday.” (Express needs)

- You can Sell by offering reasons or by referring to goals and benefits.

- “That way, we can meet the deadline for the report.” (Offer reasons)

- “With both of us contributing, we should be able to achieve our goal of completing the plan before the end of the quarter.” (Refer to goals and benefits)

- You can Negotiate by offering incentives or by describing consequences.

- “If you'll extend the deadline by a week, I'll provide you with an outline of the major conclusions that you can use for your meeting.” (Offer incentives)

- “I need to let you know that if you're not ready by seven o'clock tomorrow, I won't be available to drive you to school.” (Describe consequences)

- You can Enlist by envisioning a desired future or by encouraging the other person to join you.

- “I can see our team creating the product that finally puts this company on the map.” (Envision)

- “You're exactly the person who can attract the best candidate. You have a special ability to communicate the exciting work we want to do here.” (Encourage)

How Expressive Behaviors Work

- Tell behaviors influence by letting others know what you want and need from them. Often, people will be willing to help and support your efforts if they know what you'd like them to do.

- Sell behaviors influence by showing people reasons for and benefits from taking an action.

- Negotiate behaviors influence by offering others a fair exchange for taking or refraining from taking an action.

- Enlist behaviors influence by creating enthusiasm and putting the other “in the picture.”

Nonverbal Components of Expressive Behaviors

Expressive gestures, at least in Western cultures, are confident, free, and direct (although pointing your finger at someone while speaking will be perceived as aggressive and should be avoided). Try not to tilt your head while using these behaviors; it's a basic mammalian signal indicating, “I acknowledge your superiority.” (Watch the neighborhood dogs as they work out the hierarchy. We do the same thing, only we're a little subtler about it.) Smiling while using Tell, Sell, or Negotiate behaviors can indicate uncertainty and nervousness. (Smiling is a natural and appropriate expression of enthusiasm while enlisting.) Eye contact should be used carefully with expressive influence. Too much of it may be perceived as challenging and aggressive. Direct eye contact is best used at key points, when you want to add emphasis. The rest of the time, you can look at the other person's forehead or cheekbones. This is polite, but not invasive.

Your posture should be relaxed but erect and balanced. My aikido teacher once pointed out that the Japanese concept of “hara” or center was physically located in a space about two inches below your navel. He said that you should feel your weight centered there. If you're centered in your chest, you'll seem aggressive; if in your head, placating. Keep both feet on the floor. (I know your fourth-grade teacher told you this. Do it anyway; it makes you look and sound much more confident. Try it.) These suggestions can make a difference even on the phone or in a virtual meeting where the other can't see you—having more confident posture can translate into more confident expression. Standing up can add to your effectiveness face-to-face, especially if you're physically smaller than the person or people you're influencing. Using a flip chart or whiteboard can make this a natural part of the discussion.

Your voice should come from as low as possible in your register; breathing helps. The emotional (and vocal) tone that works with expressive influence is businesslike and matter-of-fact, unless you are enlisting the other. For that purpose, you'll use more colorful language and variable inflection. A sarcastic, negative, or hostile tone is likely to create a defensive reaction in the other person, who will conclude that you're not interested in two-way influence. Ending a sentence with an upward inflection may indicate uncertainty or a lack of confidence in what you're expressing, at least in some societies. (This may account for some misunderstandings between Canadians, who often use that inflection conversationally, and other English speakers.)

Using Expressive Influence at Work

Expressive influence is particularly useful at work early in a project or process, whether as part of a one-to-one conversation or in a meeting. The most obvious use of expressive behavior at work is simply to let others know what you want or need them to do. A good deal of time could be saved in most organizations if we were clearer with one another about this. Unfortunately, we're often reluctant to ask directly for what we want—sometimes because we're not sure it's legitimate to ask for it, sometimes because we don't want to hear a direct “no,” and sometimes because we don't want the implicit or explicit responsibilities that would accompany an open agreement.

Meetings can be dull and unproductive when participants are unwilling to express opinions and ideas. This may happen because of hidden conflict or fear of upsetting the status quo. People are also sometimes afraid to express ideas because of political or cultural concerns about whether they have the right to speak up and whether others will listen. Meetings that are consciously designed to stimulate a balance of expressive and receptive behaviors are most likely to be productive. (See Appendix C for suggested meeting process designs.)

Many conflicts in organizations arise because we're not explicit in expressing our needs and then become upset when we don't get what we want. We leave meetings with an idea of who will do what by when, but then we find that others interpreted the agreement differently. We do several favors for a colleague, believing that he or she “owes us one,” but when we try to collect a return favor, we find that the other person has been keeping a different set of accounts. We believe strongly in a course of action and are deeply disappointed when we can't convince or inspire others to join us.

All of these issues might have been prevented by the thoughtful use of expressive influence behavior, for example:

- “I'd like you to meet with me every week to review progress.” (Express needs)

- “By participating, your team will gain greater visibility with our client.” (Refer to goals and benefits)

- “I'd be glad to spend a day training your assistant on that. In exchange, I'd like you to assign him to our team for a day next week to help us complete our project.” (Offer incentives)

- “If I don't have your numbers by Friday, I won't have time to include them in the report.” (Describe consequences)

- “Here's what I see as possible. Six months from now we're all able to find every piece of data we need within minutes because we've agreed on a single database system that will work for all of us.” (Envision)

Using Expressive Influence at Home

At home, the use of expressive influence is often complicated by the thought, “I shouldn't have to tell him or her that.” We sometimes act as though mind reading is a test of familial devotion. Psychologists have introduced us to the concept of the “double bind.” (“I don't want you to clean up your room. I want you to want to clean up your room.”) In a double-bind situation, whichever choice you make is going to be the wrong one. If the child cleans up at the parent's request, that will not meet the parent's need—nor, of course, will ignoring the request.

Using conscious and effective influence behavior at home is a good antidote to the complexities of family or household communication. A good influence goal (see Chapter 8) has to be observable in the short term, so you know when you're on the right track or whether it would be better to take another approach. You can hear whether or not your housemate, son, or daughter has committed to clean the room. And you can see quite shortly afterward whether the room is clean (if you don't look in the closets or under the bed). And you'll probably learn to be pretty satisfied with that, because it cuts down on a lot of unproductive conflict and aggravation.

- “I'd like you to help me with the yard work this morning.” (Express needs)

- “There are two benefits for taking some long weekends rather than our usual vacation this summer. First, that will allow us to save enough to buy a boat for next summer, and second, I'll have enough vacation days left for us to take a skiing vacation this winter.” (Refer to goals and benefits—assuming the other is interested in either the boat or the ski vacation.)

- “If you'll agree to get a job that will pay for your room and board, I'll take responsibility for tuition and books.” (Offer incentives)

- “It's a tough situation, but I see you as the kind of person who can inspire your peers to do the right thing. I remember how you got them to support the volunteer program.” (Encourage)

Using Expressive Influence in Your Community

In community organizations, people are often not being paid to do the work that we want them to do or to take the stand that we wish they would. We may err on the side of vagueness rather than sound as if we are trying to be “the boss.” Knowing that the only rewards for volunteer work in community service or religious organizations or political action groups are intangible satisfactions and others' appreciation, we tend to “go easy,” rather than risk the loss of support and help. This can lead to a lack of energy and direction in the group or organization.

- “I believe in this project, and I'm willing to take responsibility for getting us started. Now I need two people who will work with me, starting today.” (Express needs)

- “Maria's credentials are an exact match with our criteria.” (Offer reasons)

- “If you're not willing to agree to put our name out there in support of this initiative, I'll lose respect for this organization—and I believe that others will, too.” (Describe consequences)

- “Here's what I anticipate. We're going to emerge from this crisis as a strong, united team, ready to lead this organization in an exciting new direction.” (Envision)

When to Use Expressive Behaviors

As stated earlier, expressive and receptive behaviors work together, not in isolation from one another. Overall, you'll strive for a balance of the two. Each kind of behavior has value and accomplishes certain specific results.

In summary, use expressive influence behaviors at work, at home, and in your community when

- You want people to know what you need

- You have a solution to a problem that has been expressed by the other

- The conversation does not seem to be going anywhere

- You want to generate enthusiasm and energy

- You want to bring disagreements out in the open

- You want to move toward completing an agreement or gaining a commitment

Learning to be clear, direct, and straightforward in your expressive influence takes courage and confidence. It's easiest when you do your homework, considering both facts and legitimate needs. It's also important that you be as prepared to listen respectfully to others' opinions and ideas as you hope they are to listen to yours. In the next chapter, you'll learn about the behaviors that will help you to do this.