CHAPTER 4

Insider Trading

Insider trading has long been at the core of any definition of operational and trading risks against which an entity must defend itself. The rapid spread of hedge funds and the ultra‐competitiveness of their traders has only increased the need for vigilance in this area. Significant and widespread prosecution of the crime suggests that more can be done by the industry to manage the issue. But what can be done? To paraphrase Sigmund Freud, understanding the problem will go a long way toward solving it.

What Is Insider Trading

At its most basic, insider trading is just as it sounds: trading on “inside information.” In other words, it is trading in a company's stock on the basis of material information that only people inside the company should ideally be privy to. People inside the company are prohibited from trading on such information, as is anyone who happens to come into receipt of it. Such practice has been illegal since the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934. This Act defines corporate insiders as a company's officers, directors, and any beneficial owners of more than 10 percent of a class of the company's equity securities.1

In the United States and many other jurisdictions, however, “insiders” are not just limited to corporate insiders where illegal insider trading is concerned but can include any individual who trades shares based on material nonpublic information (MNPI)2 in violation of a duty of trust. This duty may be imputed; for example, in many jurisdictions, in cases of where a corporate insider “tips” a friend about nonpublic information likely to have an effect on the company's share price, the duty the corporate insider owes the company is now imputed to the friend and the friend violates a duty to the company if he trades on the basis of this information.

The advantage and importance of “good information” in trading is perhaps nowhere better illustrated than by the legend regarding the rise of the House of Rothschild during the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon was decisively defeated by the combined forces of Britain and Prussia in 1815, but it had been far from a foregone conclusion. The well‐known story goes that a carrier pigeon dispatched to London gave Nathan Rothschild this critical information ahead of other traders. This enabled him to take full advantage in currency markets and trading in British government bonds. There was nothing illegal about this but it is not so easy to get a differentiating trading edge like that in markets these days.

Generally speaking, information is defined in the Securities and Exchange Act as anything that could have a material bearing on the stock price, such as quarterly results, positive results from research for a new drug, acquisition of a major new client, and improved sales results. A trade to take advantage of such information is executed prior to the public release of that information so that the stock price does not yet reflect it. At the point the information is released to the public, the stock price likely changes to reflect the new information, and so the insider benefits from having bought at a lower or higher (if she shorted the stock, expecting a drop in its price) price point.

A classic example was provided in recent times by that of Rajat Gupta, erstwhile managing partner of McKinsey & Co. and director at Goldman Sachs. In 2012, Gupta was convicted by a federal jury of leaking insider information gained from the boardroom of Goldman Sachs to Raj Rajaratnam—at the time, the head of the Galleon Group. The evidence of trades executed by Galleon in conjunction with phone call evidence ahead of news about Goldman were what paved the way for a successful conviction.3

In summary, deliberately trading on inside information is a crime, and legislators and regulators in the United States and other developed economies have built an infrastructure of laws and regulations to try to prevent it. In the United States, elaborate rules and procedures have been defined in the securities industry regulations determining how and when material information is released to the public, what officers can say to outsiders, and when employees can trade in their company's stock, all to ensure that the integrity of the marketplace is maintained. For example, companies release quarterly earnings results after the market closes or prior to the market opening to ensure market participants have the opportunity to digest the information prior to the onset of trading activity.

Although insider trading is sometimes described as a crime without victims, there are actually three sets of victims. First, there are the other investors in the company stock who do not have access to the inside information that the insiders have. Without the benefit of such information, investors may well be induced to sell their stock at a price below its (now) true value to the person who does have the information. This scenario is a bit like a person selling a highly valuable painting at a garage sale. The buyer is an art expert and is aware of the painting's true value but offers only a fraction of the value to the seller who is unaware of the true worth. It is clear that in this scenario, the seller has been “had.” The person selling to someone in possession of inside information is the victim of the same kind of unfairness. If the seller knew what the buyer knew, he would not sell at that price.

Second, a broad effect can theoretically occur if investors are led to conclude that the game is rigged, and they may withdraw from the market as a result. This has a negative impact on all those invested in the market. Third, in the case of firms closing (several hedge funds have been forced to do so following insider trading scandals), the folks who work there in operations, accounting, technology, and other departments lose their jobs. The employees of the organization that are forced to close down are often the silent victims.

The Industry of Insider Trading

Unlike, say, dealing in drugs, dealing in inside information is full of gray areas that dealers have been able to take advantage of. Unlike many other crimes, there is some level of ambiguity attached to insider trading that makes going after its traffickers tricky: (1) what exactly constitutes “material nonpublic information” (MNPI); (2) how to determine who is in possession of such information; (3) how to identify those who are trading on it with the requisite intent to do so; and (4) how to determine if the person providing the information benefited from doing so and if the person receiving it was aware of that. Recent court cases have highlighted some of these issues.4

However, our purpose here is not to review the legal issues at stake but to analyze the risks that are presented by insider trading cases to the risk manager and compliance officer on the trading floor. Most recently, two types of financial service firms have been prominent in the prosecution of insider trading cases in most recent times: expert networks, which are firms that provide consulting advice to trading firms, and hedge funds.

The middlemen in the insider trading industry are the industry insiders, bankers and expert networks who can (sometimes unknowingly) link the users (traders) to the suppliers (industry executives and researchers—the people with access to inside information). The insider information operation is financed by the users who are willing to pay good rates for the information. The industry is global in its scope. Many of the cases brought have turned on evidence that expert networks and investment bankers provided MNPI to their clients. There are undoubtedly many expert networks that do provide a legitimate service, helping hedge funds and analysts to research an industry and company on the basis of public information. However, there is very little regulation of such companies, and it is easy to see how such legitimate research can turn into passing on inside information.

The inside information industry would not exist without the demand of users. Cases since 2009 have brought low several major and well‐established multi‐billion‐dollar hedge funds, including Galleon Group, SAC Capital, Front Point Partners, Diamondback Capital Management, and New Castle Funds.5

So what is it about hedge funds that have given rise to this trend? Hedge funds have grown ever more ubiquitous as more and more traders from large banks, frustrated with red tape and declining pay, have left to set up their own shops. These are typically aggressive types, quite different from the portfolio managers of the more traditional and conservative asset management firms. They tend to build very sleek and streamlined organizations with very little infrastructure. It is not unusual for a young fund to have a billion dollars or more under management, with relatively few staff members in operations and a fairly junior chief financial officer (CFO) or controller. In some cases, hedge funds may take on an experienced CFO to help set up the infrastructure and systems, only to replace him or her with a more junior and lower‐paid person once the operation is in place.

A story of an ex‐colleague of mine, John, a very experienced hedge fund controller, illustrates this very nicely. John was a hardworker which was good because there was a lot of work to do. He rarely stopped for lunch and usually worked through late evening. When I first met John, I was nominally his boss but after two weeks on the job he still did not know my name. “I'm sorry but who are you again?” He asked when I came over one day to ask him a question. It was not rudeness. He was just too busy. What was his job? To make sure that the huge portfolio of securities he was responsible for were accounted for correctly on a daily basis. It took all of his time and attention. Later in his career, John was appointed CFO by the partners of a new hedge fund in 2010. The partners were former traders at a large investment bank and had no experience in establishing and running a hedge fund and the infrastructure that entails. John set up the systems and infrastructure needed to ensure investor requirements were met, valuations and returns were accurate, and so on. About two years later, the fund had raised over a $1 billion, facilitated in part by the systems and infrastructure established by John. The returns and asset basis were certainly sufficient at this point to provide the partners with a very healthy income. At this point, however, John was fired and replaced with a more junior person with no more than a year's experience. Little explanation was provided. My point in relating this story is to illustrate the little value typically associated with such functions as the CFO by the partners and portfolio managers.

In addition, compliance functions may well be outsourced by hedge funds, and there is likely no independent risk management function or investment committee to speak of. The weakness of the leadership structure on the control side of the house would be fine, of course, if all hedge fund managers had the talents and ethics of a Warren Buffett. That has certainly not been the case, and sometimes those who fall short are tempted to enhance performance by cheating. Weak control functions make them all the more likely to succeed in doing so. Raising the bar in this area would, it is true, raise the cost of entry into the industry. However, while that might penalize a little the great and the good, it would also serve to filter out the bad and the ugly.

Surveys appear to back up this view. One‐third of hedge fund professionals have seen illegal trading practices in their offices, according to a survey of 127 hedge fund professionals conducted by the law firm Labaton Sucharow, HedgeWorld, and the Hedge Fund Association in 2013.6 Nearly half of respondents (46 percent) believe that their competitors engage in illegal activity, while 35 percent say they have personally felt pressure to break rules. Of those surveyed, 30 percent have witnessed “misconduct” in the workplace. While 87 percent said they would report wrongdoing under the protections of the SEC Whistleblower Program and other such programs, at the same time, 29 percent of respondents reported that they might experience retaliation for doing so. Meanwhile 35 percent of respondents reported feeling pressured by their compensation or bonus plan to violate the law or engage in unethical conduct, while 25 percent of respondents reported other pressures. Twenty‐eight percent of respondents reported that if leaders of their firm learned that a top performer had engaged in insider trading, they would be unlikely to report the misconduct to law enforcement or regulatory authorities; 13 percent of respondents reported that leaders of their firm would likely ignore the problem. Still another 13 percent said that hedge fund professionals may need to engage in unethical or illegal tactics to be successful, and an equal percentage would commit a crime—insider trading—if they could make a guaranteed $10 million and get away with it. These responses appear consistent with events on the ground.

Trading Floors and Chinese Walls

This is not to say that large investment banks are free of the insider trading habit. However, in a banking environment, the problem often expresses itself differently.

Traders, analysts, and investment bankers work within the broad church that is the modern investment bank. Bankers work on new issuances of equity and debt, they work on mergers and acquisitions, and they provide advisory services to their clients. Their clients include global corporations, private equity funds, and hedge funds. To provide the expertise and competitive edge to their clients, they draw on the services of their analysts to provide strategy overview and forecasts for the industry, as well as insights into the upcoming moves of key players.

Chinese walls are in place to ensure that deal teams working in strictly confidential environments do not provide their colleagues on the public trading floor with access to information about their impending deals. Registers of deals are maintained so that bank employees suspend trading in those companies. Make no mistake—these controls are impressive and without a doubt mitigate the risk of insiders passing on MNPI to their colleagues over the wall. A friend of mine runs this system at one of the major banks and over the years it has grown in sophistication and authority. However, there are still gaps and it is hard to monitor how bankers can potentially profit from such information as the advantage they derive from it is not necessarily expressed in a trading transaction, rather, in advisory contracts won or lead player in an underwriting syndicate.

Meanwhile, over on the trading floor, a real temptation exists for traders to take advantage of client orders they are facilitating. Front‐running is when a firm trades ahead of a customer's large order that is likely to move the market, profiting off the inside knowledge of the impending change in the price. This activity is normally associated with equity trading, but more recently, criminal charges have been made against traders in foreign currencies.7 While such activity contravenes FINRA rules, since there is no fiduciary responsibility in this case, leveraging MNPI does not constitute an insider trading crime per se. Nevertheless, a bank's reputation would be seriously impacted if clients were to believe that the traders they are bringing their business to are also acting against their interests in executing their trades.

Monitoring traders' conversations and trades is a strong mechanism for identifying such wrongdoing. It can also show the sequencing of traders' conversations with clients ahead of orders, as they pick up their orders, and as they execute trades to meet those orders. Such monitoring can be programmed in such a way to identify cases where bankers on the “deal” side are talking to colleagues on the public trading floor on the other side of the wall, Very sophisticated tools have been identified to show on network diagrams who is talking to whom and who should not be talking to whom. Furthermore, when trades of concern are noted, conversations that have been archived can be pulled to interrogate traders over such concerns.

Raising the Bar

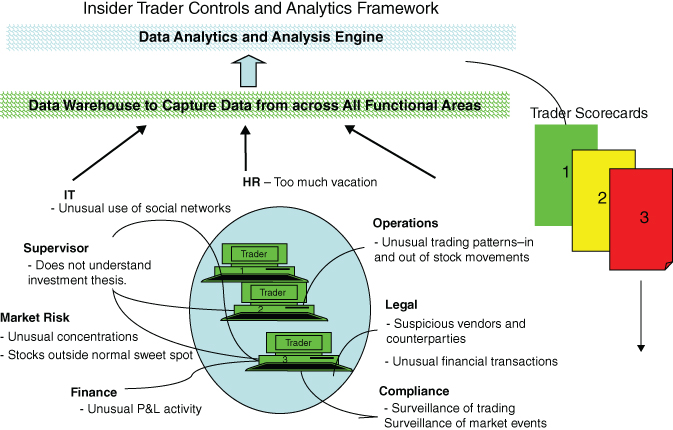

The push for raising the bar seems most likely to come from investors. For a start, one area of focus should be on ensuring greater transparency into hedge funds' investment decision and trading processes. How about, for instance, requiring discussion and then registration of any potentially “material nonpublic information” with a control group internal to the fund and independent of the trading team? Such a group, of course, is already required at investment banks and at some of the more firmly established hedge funds (voluntarily). Investments and trades can then be cross‐checked against the MNPI registry. Additionally, information upon which an investment thesis has been based is reviewed by control and compliance functions (see Figure 4-1). If the thesis is found to be based, in part, on MNPI, then the proposed investments or transactions are pulled.

Figure 4-1: Indicators of insider trading risk

Additionally, like at investment banks, an independent compliance function should surveille market events and cross‐check in an automated fashion (after the fact) for any trades ahead of those events. This type of control is absolutely standard in investment banks and it should be so also at hedge funds and other asset managers, too. With such controls and surveillance in place, it should be possible to identify trading activity that is potentially based on insider information:

- Observance of unusual trading patterns in and out of stocks, which is coincidental with market events and announcements such as merger activity or new product announcements

- Investment in stocks and companies that are outside the usual scope of a trader's portfolio or focus area

- Unusual level of focus or concentration in one stock

- An investment thesis that is not based on solid research

There are many software tools now available that can apply automated rules‐based detection engines that can identify anomalous activity. Use cases can be established leveraging prior examples of insider trading and the types of communication and trading patterns to detect wrongdoing. Investment banks and their trading operations in 2016 will generally use multiple models to detect potential insider trading, front running, collusion, and the like. Since the FX trading scandal, tools and models have also been put in place to surveille trading in those products, where before they were seen as benign areas of activity. These models and tools are audited and tested on a regular basis by the SEC, the OCC, and other regulators. Whether or not these methods are as effective as they might be is an open question that we will come back to. What is not up for debate, however, is the necessity of these checks and balances.

The experience of another ex‐colleague serves to illustrate the importance of sharing trading information more openly with the back and middle office team. Mark had been the CFO of several hedge funds and is one of the most experienced on Wall Street. Mark didn't worry too much about appearances. He did not bother to comb his hair or clean his thick glasses. But he was brilliant and he could do his job blind folded. Despite this brilliance, he has twice found himself on the receiving end of portfolio managers who did not provide sufficient transparency into the investment process. The first time, as CFO of a credit fund, he did not have full transparency into the extent of subprime investments in the portfolio. The fund's value was subsequently totally wiped out during the 2008 Financial Crisis. The second time, as CFO of an equities fund, he was not provided with information regarding the nature of the data upon which investments and trades were being made, some of which was later alleged (with ultimately a guilty conviction for several of the portfolio team) by federal prosecutors to be based on inside information. As CFO, Mark was blindsided in both cases, in part because he was, in effect, treated not as an investment partner but as back office. Had he been fully brought into the investment process, with much greater transparency, he may have been able to help avert the crises that overtook the funds in both cases.

Portfolio managers require supervision but very rarely do they ask for it, get it, and accept it. The example of Mark illustrates that there is a heavy unseen cost to insider trading, which is often borne, when firms close, by the hard‐working employees in support functions. They, in addition, have not been able to reap the rewards harvested by those responsible for the issues at hand. Ultimately, it becomes harder to attract and retain talent into infrastructure roles in hedge funds and banks when the risks are seen as being too great and the rewards too little relative to the front office. It appears that the low‐cost infrastructure, ethical shortfalls, and structural inadequacies of hedge funds are amongst the most pressing issues to address.