CHAPTER 6

The Mortgage Mess

In January 2013, the US Justice Department slapped Standard & Poor's with a civil law suit for fraud,1 accusing the credit rating agency of inflating the ratings of securitized mortgage products in the years leading up to the 2008 Financial Crisis. However, the beginnings of the mortgage mess trace back to 2006 and 2007 and some of the key risk indicators that, in retrospect, should have been cause for greater circumspection on the part of some risk managers.

Much of the criticism aimed at Wall Street at the time of the financial crisis and since has been related to its role in the mortgage industry. Creating and trading in securities consisting of groups of mortgages had become a major profit center for banks. It was in no small part the critique of this particular activity that led to the Volcker rule and the proposal to ban proprietary trading for investment banks.

Mortgage Securitization

The key to the mortgage growth or securitization lay in the fact that the greatest risk for a bank is the credit risk it takes on when it executes its basic function—lending money to clients. The implosion of the savings and loans industry was largely due to the large number of loan defaults in the 1980s. After this, broadly speaking, there was no longer the same readiness amongst financial institutions to take over the singular risk of lending money to individuals for the means of purchasing a house. Securitization, then, became a primary means by which the housing market was resurrected in the United States.2

Mortgage securitization puts a group of mortgages into a single asset and thereby allows banks to pass on the risks of default to a far wider circle of risk takers. Investors who buy the asset are buying the right to receive a set of cash flows—the mortgage payments—from the underlying mortgages. Should one of those mortgages default or refinance, the risk is ideally sufficiently diversified by the other mortgages to ensure the impact is minimized.

As securitization and financial engineering grew more sophisticated, bundles of mortgages were put together into CDOs (collateralized debt obligations), and this allowed investors flexibility to choose the level of risk they took on. These are called strips. Investing in the strips with higher risk profiles within the asset—that is, homebuyers assessed as having a higher likelihood of default—is rewarded with higher yields. This spread of the risk made financial and economic sense and enabled expansion of the home ownership market in the United States.3

Unfortunately, other less‐attractive features of the market were part and parcel of these developments. First, the complexity of some of the assets made it hard to attach fair value to them, creating potential for the type of mispricing discussed in Chapter 4. These issues were never properly addressed. Second, the split between the banks trading in the assets and the originators of the mortgages meant that the underwriting standards maintained by the originators were not necessarily transparent to those trading in the assets. Furthermore, underwriting standards deteriorated as certain mortgage companies sought an ever‐larger slice of the pie. It is fair to say that the securitization process at some point failed investors, as it could be seen as allowing certain firms to write poor‐quality loans. Firms were able to increase production by extending loans to people who had no practical ability to repay them. The originators were able to quickly move the poor assets off their balance sheets through the sale of the pools of the loans they had amassed to their investors. While 4 percent of prime fixed‐rate securitized mortgage loans in the triple‐A universe issued in 2004 were judged in 2010 to be below investment grade, 90 percent of those in 2006 and 2007 were.4 These flaws in the securitization process, unproblematic at first, led to a negative circle of activity fueled by players who only knew a rising housing market. A rising tide raises all boats, but when the tide goes out, all boats get stuck in the sand. There were indicators that the market for mortgage‐based securities was headed south by 2006, but they were largely ignored.

Indicators of Risk

Some people were paying attention to the warning signs in 2006, and even earlier, and acted accordingly. Others were either paying attention but did not feel compelled or able to act or simply didn't notice the risks growing around them. This is a story of these different risk managers: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

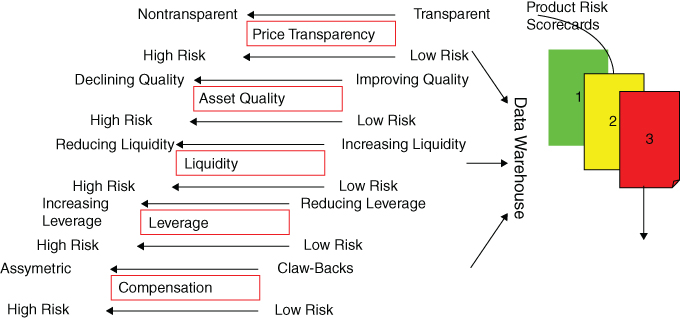

The first indicator of risk back in 2006 was a decrease in asset quality. (Figure 6-1 provides a generalized framework for risk indicators.) As has been well documented, the mortgage sales industry expanded tremendously through the early part of the 2000s. To maintain production levels and continue to expand the consumer market, the origination of risky mortgage products with adjustable rates in the “subprime space” became far more widespread: Commentators have estimated that the proportion of subprime mortgages grew from 8 percent in 2004 to about 20 percent in 2006.5 This trend negatively impacted the underlying quality of the assets being packaged. Investment banks repackaged them into securitized products in 2006 and 2007, making their future cash flows far more vulnerable to changes in underlying market conditions. Risk managers worth their salt took note of the changes in underlying assets and took steps accordingly. Goldman Sachs took aggressive steps, prudently as it turned out, to hedge its positions with regard to the housing market in 2006 and came out as well as any of the major trading houses from the crisis. Many risk managers, however, did not take such steps and, in fact, continued to look for ways to double down on their long positions. Citigroup CEO Charles O. Prince, interviewed by the Financial Times in July 2007, said, “As long as the music is playing, you've got to get up and dance,” before adding the punch line, “We're still dancing.”6

Figure 6-1: Indicators of product risk

The second indicator of risk was a lack of transparency in pricing. These bonds were very complex and the detail behind their underlying assets hard to value. The rating agencies were able to confer value in the marketplace by the ratings they determined. The action just taken by the Department of Justice against S&P underlines the difficulty facing banks. In this context it was important for banks to develop independent means of assessing the value of these securities and of their future prospects. There were several traders who understood that the ratings did not necessarily coincide with market realities—Steve Eisman, Gregory Lippman,7 and John Paulson,8 to name just three. Such traders had developed an independent basis for their assessments of value. It is worth noting that when the market was positive, such lack of transparency helped assets of lower quality to attain higher values. When it turned negative, however, that very lack of transparency did not help products that were higher quality: All tended to be tarred with the same brush. Portfolio managers and traders who did detailed analysis of the assets and believed they had a quality portfolio were not necessarily helped if they missed that bigger picture.

The third indicator was a move toward increased leverage that was taking place. It is well known, for example, that leverage levels at Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns were at historically high levels at the time of their demise in 2008. Hedge funds also looked to increase leverage to increase yield to investors. For example, Bear Stearns launched an “enhanced leverage” version of its High Grade Credit hedge fund in September 2006. While the move toward enhanced leverage was encouraged by investors who were looking to enhance their returns, it was also an indicator of rising risk.

The fourth risk indicator was reducing market liquidity. When liquidity starts to leave the market, risk increases exponentially for those who hold significant long positions. That is why metrics around liquidity are vital to track. Between 2008 and 2011, liquidity literally left the building and those banks, asset managers, and investors holding any type of mortgage security could do nothing with them except count their losses each month. Monitoring for, and being sensitive to, real‐time small changes in liquidity levels that suggest larger potential changes could be on their way is extremely useful.9

The fifth and final indicator is asymmetric compensation structures: traders paid well for good results without any negative consequences for poor results or negative behaviors. In 2008, the term clawback had barely been coined, and clawing back of traders' profits was a reasonably rare event, so this was at best a blunt tool at that time. The increased use of clawbacks has been an encouraging development since that time, though a certain level of clarification and consistency regarding their application would be beneficial. Banks that are more consistent with clear guidelines for their application should be better positioned to manage this type of risk.

At a certain point, the securitized mortgage market turned in a most decisive way but nobody could tell you exactly when that tipping point was reached. As the changes in the mortgage market coursed their way to the trading floors of investment banks and hedge funds, Goldman's risk managers were watching and took actions accordingly when their indicators pointed to changes in market conditions. Others who failed to do so were left holding the bag. This survey of risk indicators, which is hardly exhaustive, does nonetheless highlight the importance of clawbacks and the need for risk managers to understand and track risk indicators from each of the major risk disciplines: market, credit, and operational.

The Aftermath

Not only did Wall Street firms suffer losses in the market from securities they held, they also suffered losses because they invested in companies that originated mortgages and then sold them to those that securitized the loans. Bank of America was the most notable to do this, with its ill‐fated purchase of Countrywide Financial, but other banks that made purchases, sometimes at the behest of regulators in the case of JPMorgan and Bear Stearns, suffered a similar fate.10 In the end, not only did Bank of America and others have to write down the value of such operations and many of the loans that they had written, they also inherited regulatory issues that culminated in fines or a requirement to compensate Fannie Mae or other agencies for loans that were not what they purported to be in terms of underlying loans riskiness. Additionally, the increase in loan default led, in turn, to a rush to foreclose and a further round of regulatory actions, some of the most sizable in history. This is one strong argument for a more deliberate and risk‐based strategic planning process on the part of banks. Seven years later, the price of failing to do so came due.

What the story illustrates is not the wickedness of Wall Street but the level of complexity that was created. An on button had been pressed, but there was no off switch or set of brakes that could be applied. In the end, the momentum generated by the securitization industry was too great to stop. There could only be one ending to this trip.

In addition to the individual improvements that firms can make to their risk management processes, making sure that there are brakes that can be applied when the market overheats is of critical importance. The way this works in most markets is through the organization of a marketplace, which provides clearer indicators of its direction, levels of supply and demand, and pricing to participants. The moves made in the past several years toward a central, transparent marketplace for fixed‐income securities should support this development.

However, risk managers must still be vigilant to markets exhibiting the type of characteristics of the mortgage underwriting market that we reviewed earlier in the chapter. Cognitive tools and technologies can be applied to automate the detection of such concerning market features as reducing asset quality, shorter product approval timelines, and evidence of waivers of the usual credit score features in, for example, communication between customers. The use of such tools, in combination with the judgment of the risk manager, will support reducing the likelihood of such future disasters on both the micro and macro level.