CHAPTER 19

The Future Is Unknowable, the Present Burdensome; Only the Past Can Be Understood

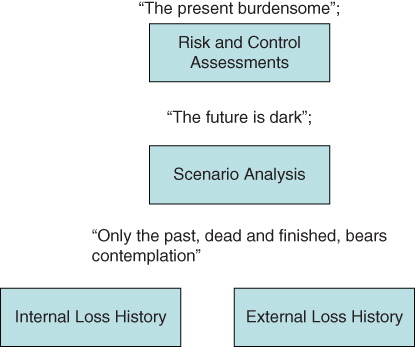

If one wants to change the future, one first has to understand the past. The first task of operational risk is to do so by capturing and analyzing the losses of recent history and the ability of the risk and control infrastructure to address, prevent, and mitigate these losses in the future (see Figure 19-1).

Figure 19-1: Understand the past to mitigate the future

The key tools in the hands of operational risk are internal loss incidents, external losses, risk scenario analysis, and risk and control assessments.1

Each element has its own purpose and is typically collected in a relatively siloed fashion. Executing these processes effectively will educate different parts of the firm about its current risks. Those firms able to aggregate the data effectively, however, can create a powerful platform for more forward‐looking analysis. Developing such predictive capabilities is where today's CEOs need to be if they are going to turn the tables on risk. Let's look at each of the core components.

Internal Loss Incidents

Internal risk incident capture is the most basic obligation under Basel II requirements (see Table 19‐1).2 The tables discussed in the risk assessment section in the previous chapter could not be created without this basic data collection being performed. The obligation is important for two reasons: first, it is often seen as the most important data point behind the ability to forecast future operational risk losses; second, it enables the firm to learn from its mistakes by ensuring documentation of event causes and control weaknesses.

Table 19‐1 Incident Capture Systems: Basic Information about Each Incident Is Captured

| Incident Description | Date | Risk Category | Business Unit | Loss Amount | Location | Control Failure | Mitigation Required? |

| Incorrect stock purchased | March 3, 2014 | Execution errors | Equity trading | $10,000 | New York | N/A | No |

| Algorithmic trade error | March 12, 2014 | Execution errors | High‐frequency trading | $1 million | London | Code change control | Yes |

| Wire payment error | March 15, 2014 | External fraud | Trade settlement | $500,000 | Mexico | Due diligence | Yes |

Taking the first point, banks are obliged under Basel II to calculate and set aside sufficient capital to ensure that they can fund future losses. Banks develop models to measure what such an amount of capital would be, and past loss incident history is generally the most important input to the model.

There are, in broad terms, three types of losses: small and frequent, large and infrequent, huge and very infrequent. A few examples are provided in Table 19‐2 and described as follows.

Table 19‐2 Internal Loss Incidents

| Incident | Loss Amount | Description | Control | Control Breakdown? | Remediation Required? |

| Small and frequent: Wrong Way Trade | $10,000 | Trader bought shares instead of sold | Sales order/Trade confirmation | No | No |

| Large and infrequent: Wrong Way Trade | $10 million | Trader bought long position instead of short | Second eyes review/Trade confirmation | Yes | Yes |

| Very large and rare: External fraud | $500 million | Sales team lent money to borrower who presented false identity and assets | Due diligence/Loan document review | Yes | Yes |

Example 1: Small and Frequent

A trader sells 1,000 shares when he was supposed to buy them. The loss after he has reversed the trade might be $10,000 or even a bit more on a volatile day, but not much more. Typically, such incidents occur frequently in large trading businesses, especially equity trading and wealth management firms. Counterintuitively, the documentation of several incidents a day is an indication of a healthy risk and control framework. Typically, little can be done to remediate or prevent a certain amount of these types of incidents from occurring.

Example 2: Large and Infrequent

A structured trade is executed as a buy instead of a sell and the resulting hedging trade is executed the wrong way. By the time the position is sold and corrected, the firm has lost $10 million. Such incidents are more likely to occur in fixed income, where the complexity is greater and single trades can generate large losses or gains in a relatively short period of time. For a trade error of this nature to amount to a significant loss requires a significant lapse in controls to have occurred and would warrant a remediation plan to be put in place.

Example 3: Very Large and Rare

Then you have incidents that are larger, rarer, and very hard to predict. Consider a loan made to a person purporting to be from a creditworthy entity and has a certain amount of assets as collateral. In the end, the person is not who he claims to be, either has no assets or no traceable assets, and fails to pay the loan premiums and repay the capital as required under the loan terms. A loss of $500 million is realized. Setting aside capital to cover events large in impact like these is required by the regulators and under Basel supervision.

Daniel Kahneman's work3 looks at the fallacy of deriving conclusions from too small a sample size. The danger to be avoided is reading too much into a small number of large incidents from a future perspective. The sample size of very large incidents is certainly small and needs to be modeled and weighted appropriately. The real importance attached to large incidents, however, is not as data points in a prediction of future losses but as a rich source of information for risk managers trying to learn how to avoid risk. The future likelihood of a major risk calamity is determined not by naked statistics but by risk management effectiveness: learning from one's own and other people's mistakes. If one fails to learn the lessons behind such events, one is doomed at some point to repeat them. Such information can be used to predict future risk events more effectively, but more analytical tools and honesty are needed to acknowledge where the lessons have not been learned and the exposure still exists.

Despite this, one cannot even begin to imagine the time and resources dedicated to capturing all the losses that occur:

- Capturing all incidents is not a simple exercise.

- Silos and confidentiality requirements between business units can block simple workflow requirements.

- Whether the loss is $10,000 or $10 million, the data requirement is the same. That means the same level of effort is potentially required to capture small losses as large losses.

- Educating people in the business on the importance of capturing incidents is never sufficient.

Often, it is those who are not familiar with the reporting requirements who are most familiar with the incidents that occur. Hence, you may get rogue trading incidents and even large trade execution losses not reported or even discussed internally with operational risk officers. That is why a risk manager worth his salt is always putting his nose in where it is not always wanted, asking questions, sometimes uncomfortable ones. It is not the best way to make friends, but it is the only way to find out what is really going on. An open society will help immensely in this respect.

External Incidents

Risk departments are also asked to collect incidents that occur at peer institutions. This is an important data point to support two pieces of risk analysis: first, to help analyze whether what happened at peer institutions could happen internally; and second, to determine if internal incidents overall are trending higher or lower than at peer institutions. Too often, though, risk departments fulfill the letter of the law by providing reports of the incidents without enquiring further. Sometimes that is fine, but sometimes further work is needed to determine if what just happened at a peer bank could also occur at your institution. A few examples are provided in Table 19‐3 and described as follows.

Table 19‐3 External Loss Incidents

| External Incident | Peer Bank | Loss Amount | Risk Applies Here | Effective Controls? | Mitigation Plan Required? |

| LIBOR price fixing | Major UK bank | $473 million | Yes | No | Yes |

| Rogue algorithm | High‐frequency trading firm | $300 million | Yes | No | Yes |

| AML fine | Global investment bank | $1.7 billion | Yes | No | Yes |

Example 1: LIBOR Settlement at Peer Fixed Income Trading Firm

Consider a peer bank that has settled with the UK financial regulator for millions of dollars for fixing LIBOR (London Interbank Lending Rates) rates. The CRO has asked the head of operational risk to identify whether this is a risk at their bank and whether or not controls need to be improved to address the risk.

First, the head of operational risk asks a simple question: Is the bank a member of the group of banks that send in the lending rates used to determine the LIBOR rate? If it is not, then the case can be closed, although the CRO may choose to broaden the investigation to any valuation processes potentially open to price fixing. If that happens, interviews should be conducted with the key people responsible for executing the valuation processes to identify any control gaps. A policy that clarifies the guidelines for conducting such work, the sign‐off processes, should be rolled out in compliance with regulatory requirements.

Example 2: Rogue Computer Algorithm Incident at Peer Equity Trading Firm

The question must be asked as to whether the bank is in the algorithmic trading business. If the answer is yes, information needs to be gathered quickly as to what happened exactly at the peer institution. Anyone with contacts at the bank should be brought in to understand how the problem occurred and what control weaknesses were at fault. Then interviews should be held with IT and operations regarding any issues or incidents identified in the algorithmic trading area. An action plan should be drawn up for any control weaknesses identified and people made responsible for closing them.

Example 3: AML Fine by Regulators

This is a major incident and requires full engagement with the relevant line of business. Interviews with the bank's chief financial crimes compliance officer identified issues with AML processes and procedures across multiple business lines, including failures to identify all suspicious transactions and risky clients. A thorough review of AML processes and procedures across all lines of business is ordered, and the findings will be shared with regulators.

Apart from the important job of immediate response to an event, external incidents are also important in the scenario‐planning component to help participants think through possible worst‐case loss scenarios.

Scenario Planning

The third element of the operational risk framework under Basel II is scenario planning (see Table 19‐4). This is the most difficult and contentious aspect of the operational risk framework, and approaches vary from firm to firm. Some firms favor a workshop format, bringing key business leaders together to discuss each of the top risks while others conduct a less discursive approach. Whatever the approach, the same objective holds: to identify the highest‐impact potential loss in each risk category and make an estimate of its potential frequency. The other commonality is the leveraging of business knowledge of the managers of each line of business. The difficulty most regulators have with any of these approaches is generally the lack of evidence for the decisions that are made. Second, it is sometimes hard to avoid coming away with the view that participants have taken a somewhat rosier view of the future than can be justified. Here are some examples of such workshops.

Table 19‐4 Operational Risk Scenarios

| Risk Scenario | Largest External Loss | Largest Internal Loss | Max Loss from Future Event | Frequency |

| Litigation from underwriting risk | $2 billion | $200 million | $300 million | Every 10 years |

| External fraud | $1 billion | $50 million | $100 million | Every 5 years |

| Unauthorized trading | $7 billion | $50 million | $100 million | Every 5 years |

| Fat‐finger error | $1 billion | $2 million | $10 million | Every 5 years |

Example 1: Underwriting Business and Risk of Litigation

Your bank is conducting a scenario workshop for the underwriting business. The key risk category has been identified as litigation from shareholders due to losses following a bankruptcy of a security underwritten by the bank.

The operational risk department has put together a list of external and internal incidents that occurred at its and other banks. External incidents reviewed by the group include the Citigroup and JPMorgan settlements with shareholders of Enron and WorldCom of over $2 billion each. They also review the Bank of America Settlement with Merrill Lynch shareholders for over $2 billion. The largest incident identified internally at the bank was a loss of $300 million 10 years ago.

The group, after reviewing these incidents, is asked to estimate the largest potential loss from such an incident at the bank. The group's estimate for a worst‐case scenario is $300 million, based on this rationale: first, this bank has a very careful process for determining whether or not to join an underwriting syndicate, hence, Enron and WorldCom both failed to make it through that tough process; second, this bank only underwrites as part of a large syndicate, which has the effect of diversifying the risk from a large single loss.

While both parts of the rationale may sound reasonable, they certainly can't be seen as foolproof measures against a future decision to underwrite an issue that later on turns out to have been much greater risk than appeared to be the case or against a decision to be more closely associated with an issuer than was normal. The issue is that an event that happens every 10 years is not likely to attract a lot of attention to mitigate so is unlikely to drive fundamental change in the way that the risk is managed.

Example 2: Equities Trading and Rogue Trading Risk

Your bank is conducting a scenario workshop for the Equities Trading Business. The key risk category has been identified as internal fraud and potential losses from rogue trading incidents.

The operational risk department has put together a list of external and internal incidents that occurred at their and other banks. Previous external incidents reviewed include the relatively recent rogue trading incidents at UBS and Societe Generale. The original set of internal incidents included in the documentation for the workshop only had two internal incidents, both of which were of far less financial impact, under $50 million, than the external incidents. The workshop group, consisting of leaders of the control and operational functions, after reviewing these incidents is asked to estimate the largest potential loss from such an incident at the bank. The group concludes that the most severe loss that could be reasonably expected would be $100 million, an amount far less than the worst losses at peer banks.

While the worst losses, on a statistical basis taking all banks into consideration, are incredibly rare events, it is hard to prove that they could not occur again. The rationale against such events reoccurring is that a lot of work has been done since those prior events to make the bank safer and that the controls are stronger than they were. Again, however, such a conclusion is hardly foolproof against such an event reoccurring.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion from workshops such as these that the influence of prior internal losses is a very strong influencer of decisions. One can minimize this influence by not including the past in the documentation, but then participants have nothing to guide them. Some banks have begun to experiment with analysis of risk factors to ground the workshops in analytical frameworks that can help the predictive process. This may just be another way of anchoring the discussion, but it may be too much to think one can ever avoid any anchoring bias.4 Workshops like these can be powerful means by which scenarios can be discussed and avoidance strategies proposed, but they are not necessarily the most efficacious means of measuring the exposure to future losses. Again, the perceived likelihood of a significant event occurring is very infrequent, and so the efficacy of putting in place thoroughgoing mitigation strategies is likely to be questioned without better methods for identifying risk factors.

Risk and Control Assessment

Risk and control assessment is another significant component of most banks' operational risk frameworks, though it is not explicitly required under the Basel II regulations. What is required is for the operational risk framework to take into account business environmental factors—in other words, the control effectiveness of the organization. The theory is that once you have the incidents—internal and external—and an assessment of the firm's control environment, then you can make a better stab at assessing the likelihood of risks occurring or reoccurring. The only way really to assess the control environment is by performing risk and control assessments on a regular basis.

The building blocks of the assessment process are the risk and control dictionaries that the firm has developed. Every part of the organization should be assessing a common set of risks and controls. In a large organization, this means the ability to aggregate risks in a way that can highlight areas of common risk and control. Let's consider some examples, illustrated in Table 19‐5.

Table 19‐5 Risk and Control Assessment

| Risk | Inherent Risk Assessment | Control | Control Assessment | Residual Risk Assessment |

| AML—Client moving illicit funds | High | AML detection program | Ineffective | High |

| KYC—Not knowing client is a mafia member | High | Know Your Client program | Ineffective | High |

Example 1: Equities Trading—Risk of Anti–Money Laundering

The risk is that the firm is trading on behalf of clients using illicit sources of funds, such as those from drugs or piracy. The inherent risk (i.e., the level of risk assuming the controls are not in place) was assessed as being critical, owing to the high penalties recently imposed on peers for similar infractions and the ethical reputational issues involved. The controls such as AML documentation requirements and fund transfer surveillance were judged as being largely ineffective, and so the residual risk (the level of risk after effectiveness of controls are taken into account) was seen as high.

Example 2: Asset Management—Risk of Not Knowing Your Client

The risk of not knowing your client (KYC) is the same, more or less, as AML, since the KYC regulations are in place to prevent money laundering. In this case, the controls were also judged to be largely ineffective so the residual risk was assessed as high.

The risk dashboard has been designed to escalate risks that are judged to be residually high by more than one business area. Unfortunately the AML risk was not picked up by it, since the two risks were seen as different rather than the same.

The first good practice is to ensure that risks are grouped together under common descriptors and recognized as such. The second good practice is to ensure that a risk measurement matrix (discussed in Chapter 18) is in place and leveraged to ensure consistent ways of measuring risk impact across lines of business and geographies. In the AML example, for instance, high risk might be argued for on the basis of a high likelihood of a large penalty being imposed on the firm for failing to follow AML procedures. The third good practice is to use quantifiable measures as much as possible to determine the risk level: by leveraging the evidence of prior losses and by developing metrics that can provide a quantitative basis for determining control effectiveness. Controls that can be rated on the basis of objective, rather than subjective, bases will lead to more accurate estimates of their effectiveness and, in turn, of the level of residual risk. The fourth good practice is ensuring that high residual risk assessments are followed up with remediation plans to improve controls and prevent the risk from occurring. As has been seen in the recent penalties imposed on banks by regulators in the United States and overseas, there is much still to do in many areas.

While an organization excelling in these areas can certainly collect a lot of useful information and gain some benefits, it will not increase its ability to see around corners or avoid falling into rabbit holes. While it is critical to learn from past mistakes, it is insufficient to prevent them from being repeated. To do so requires us to create some preventive measures and forward‐looking analytic capabilities. We will explore this in the next chapter.