CHAPTER 7

Ponzi Schemes and Snake Oil Salesmen

This chapter is concerned with financial institutions that use illegal methods to gain investors and buyers. The first section deals with investment managers who do this by falsely pumping up their performance in the manner of Ponzi schemes ala Madoff. The second section deals with financial institutional salespeople who smooth‐talk and graft their way into the graces of individuals, pension funds, institutional clients, banks, charities and trusts through the old‐fashioned methods known as bribery and corruption. Finally, we will then look at how these tried and trusted methods for fooling people and for taking advantage of fools can be countered.

Ponzi Schemes

Much has been written and said about Bernie Madoff, but he was neither the first nor the last to conjure a money‐making machine out of thin air.

In 1920 in Boston, Charles Ponzi's supposed arbitrage scheme was just a masquerade for paying off early investors with the deposits of later investors. Ponzi claimed he would double investors' money in 90 days through a bizarre plan to buy and resell international postal‐reply coupons. Ponzi collected more than $8 million from about 30,000 investors in just seven months before the scheme collapsed. He served five years in prison for using the mail to defraud. Thus, the Ponzi scheme was born. A bit later, Swedish businessman Ivar Kreuger, known as the match king, built his own Ponzi scheme, defrauding investors based on the supposedly fantastic profitability and ever‐expanding nature of his match monopolies. The scheme collapsed in the 1930s, and Kreuger shot himself.

Bernie Madoff, however, was responsible for the most significant Ponzi scheme in history. On December 10, 2008, Madoff made an admission to his sons that his investments were “all one big lie.” The following day, he was arrested and charged with a single count of securities fraud. At the time of his arrest, the losses were estimated to be $65 billion, making it the largest investor fraud in history. It is probably fair to say that calculations have still not arrived at an accurate estimate of investors' loss, but it is fair to say that they were in multiple billions of dollars. Madoff was sentenced to 150 years in prison.

Much has been written about Madoff, including several books about the scheme, how it was able to continue for so long, and how he was able to keep the scheme a secret from even those closest to him. One of the interesting things about Madoff, of course, is that he was able to fool seemingly very smart people, including the most sophisticated of investors. Madoff founded the Wall Street firm Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC in 1960, and was its chairman until his arrest. He was active in the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD), a self‐regulatory securities industry organization, serving as the chairman of the board of directors and on the board of governors. In 1992, The Wall Street Journal described him as “one of the masters of the off‐exchange ‘third market’ and the bane of the New York Stock Exchange. He has built a highly profitable securities firm, Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities.”

This operation was, of course, very helpful in burnishing Madoff's reputation on Wall Street as he started to build out the fund side of the business in the 1980s. He gave interviews to the press and was able to talk intelligently about his esoteric hedging strategy. However, a few analysts performing due diligence had been unable to replicate the Madoff fund's past returns using historic price data for US stocks and options on the indexes, his claimed strategy. Barron's raised the possibility that Madoff's returns were most likely due to front running his firm's brokerage clients.

Mitchell Zuckoff, professor of journalism at Boston University and author of Ponzi's Scheme: The True Story of a Financial Legend, says that “the 5% payout rule,” a federal law requiring private foundations to pay out 5 percent of their funds each year, allowed Madoff's Ponzi scheme to go undetected for a long period since he managed money mainly for charities. Zuckoff noted, “For every $1 billion in foundation investment, Madoff was effectively on the hook for about $50 million in withdrawals a year. If he was not making real investments, at that rate the principal would last 20 years. By targeting charities, Madoff could avoid the threat of sudden or unexpected withdrawals.”

In his guilty plea, Madoff admitted that he hadn't actually traded since the early 1990s, and all of his returns since then had been fabricated.

Madoff, of course, invested in the sort of outward signs of success and swagger that likely filled those around him, including clients, with confidence. Madoff maintained sole ownership of the company throughout its history and retained close control over back‐office oversight functions. He was thus able to ensure that only he knew about the various steps in his fictitious scheme, such as maintenance of a fictitious banks address to which all bank document requests were sent and intercepted (by him), as well as falsification of bank statements and confirmations.

One can easily understand why Madoff's investors were misled. Its reputation as a hard‐to‐get‐into fund provided allure. The support of trading experts burnished Madoff's reputation. The implication of an edge provided by the securities operation was perhaps the most persuasive reason why Madoff was seen as such a solid bet. Indeed, The SEC investigated Madoff in 1999 and 2000 about concerns that the firm was hiding its customers' orders from other traders, for which Madoff then took corrective measures. In 2001, an SEC official met with Harry Markopolos at its Boston regional office and reviewed his allegations of Madoff's fraudulent practices.1 The SEC claimed it conducted two other inquiries into Madoff, but did not find any violations or major issues of concern. In 2007, SEC enforcement completed an investigation it had begun on January 6, 2006, into a Ponzi scheme allegation. This investigation resulted in neither a finding of fraud nor a referral to the SEC Commissioners for legal action.

Concerns were also raised that Madoff's auditor of record was Friehling & Horowitz, a two‐person accounting firm based in suburban Rockland County that had only one active accountant, David G. Friehling, a close Madoff family friend. Typically, hedge funds hold their portfolio at a securities firm (a major bank or brokerage), which acts as the fund's prime broker. This arrangement allows outside investigators to verify the holdings. Madoff's firm was its own broker‐dealer and allegedly processed all of its trades. Ironically, Madoff, a pioneer in electronic trading, refused to provide his clients online access to their accounts. He sent out account statements by mail, unlike most hedge funds, which emailed statements.

Four years after the 2008 discovery of Madoff's scheme there was a similar incident involving Peregrine Financial Group, a firm that operated for over 20 years in relative obscurity in Cedar Falls, Iowa. Peregrine's founder, Russell Wasendorf Sr., following a suicide attempt and business failure, pled guilty and was sentenced to 50 years in prison for four counts of embezzling clients out of more than $100 million, commission of mail fraud, and two counts of lying to federal regulators. This disturbing episode highlighted once again the risk of fraudulent investment schemes paying investors returns from their own money or subsequent investors' money.

Wasendorf's company, known to most of its clients as PFGBest, developed a reputation, just like Madoff's did, in its formative years for pioneering new electronic trading platforms and reliable customer service. One can still find on its website a steady accumulation of top futures broker awards, even through 2012, and a long list of customer testimonials. Wasendorf, like Madoff, became an industry acolyte and was sought out to take on industry guardianship roles. He served most significantly on the National Futures Association (NFA), the self‐regulated watchdog of the futures industry, Advisory Committee. He invested in the sort of outward signs of success and swagger that likely filled those around him, including clients, with confidence: a spectacular headquarters, private jets, and so on. Like Madoff, Wasendorf maintained sole ownership of the company throughout its history and retained close control over back‐office oversight functions. According to his own admissions, he allowed no one else at the firm to communicate with regulators, auditors, and banks. He was thus able to ensure that only he knew about the various steps in his fictitious scheme, such as maintenance of a fictitious banks address to which all bank document requests were sent and intercepted (by him), as well as falsification of bank statements and confirmations. As with Madoff, the PFGBest's auditor was a one‐person shop2 based at the accountant's home. We have read this story before. Like Madoff, Wasendorf's firm employed a small army of sales people who worked to introduce new accounts and new money to the firm. Also like Madoff, the lies finally caught up with him but only after a very long run.

Stanford Financial Group, was another Ponzi scheme that was identified in the late 2000's. In early 2009, the founder, Allen Stanford, became the subject of several fraud investigations, and on February 17, 2009, was charged by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) with fraud and multiple violations of US securities laws for alleged “massive ongoing fraud” involving $7 billion in certificates of deposits (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jun/14/allen‐stanford‐jailed‐110‐years). Ultimately Stanford was sentenced to 110 years of prison. His exploits were detailed in many newspapers at the time: The UK Guardian newspaper covered his specific methods in some depth in a profile written on February 20, 2009, and the New Yorker had a longer profile in March 2009. Like the other Ponzi schemers we have looked at, Stanford was a past master at simulation of high returns, making good use of excellent connections and burnishing the high life he lived, in this case, in the Carribean.

More recently, Platinum Partners has been alleged to be the subject of a similar scandal. In December 2016, federal agents arrested Mark Nordlicht, a founder and the chief investment officer of Platinum, and six others on charges related to a $1 billion fraud that led the firm to be operated “like a Ponzi scheme,” prosecutors said (http://www.wsj.com/articles/platinum‐partners‐executives‐charged‐with‐1‐billion‐securities‐fraud‐1482154926). This case shows that, far from going away, the danger posed by Ponzi schemes is ever present. See Table 7‐1 for an overview of recent infamous Ponzi schemes.

Table 7‐1 Losses from Recent Ponzi Schemes

| Firm | Year | Loss (in US billions) | Product |

| Platinum Partners | 2016 | ∼$1 | Hedge Fund |

| Peregrine | 2012 | Unknown | Futures Broker |

| Stanford | 2011 | ∼$8 | Bank |

| Madoff | 2009* | ∼$17 | Hedge Fund |

*Early estimates of losses of $60 billion to investors were not accurate as they included fictitious gains on original investments. The court appointed trustee estimated actual losses to investors to be closer to $18 billion.

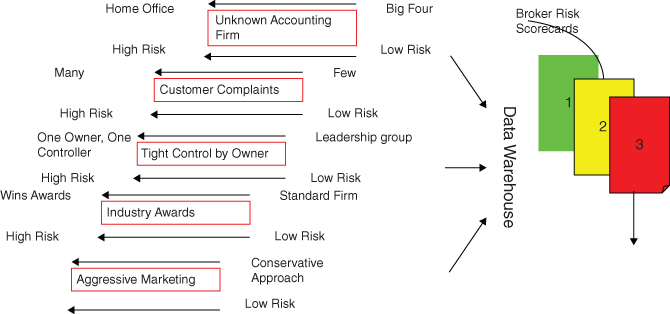

Regulators and Fraud

At the time the Madoff scheme was revealed in 2008, people found it hard to understand why and how the SEC failed to uncover it earlier and why Madoff was able to get away with it for so long. History is always written, it can't be helped, from the perspective of the outcome. In retrospect, and from the various red flags, it seems obvious that Madoff was a crook. Yet, as one member of the SEC's enforcement team told me, it was virtually impossible to tell: redemptions to investors' requests were always paid out on time; investors' statements looked completely authentic; and there was a separate broker‐dealer with its own set of assets that were real. All of this made it extremely difficult to uncover the scheme. After Madoff was charged, as already discussed, some industry analysts said they had reported a concern to the SEC, which the SEC allegedly failed to fully investigate However, relative to the hundreds of investors who had money with Madoff, the number of those who thought something was amiss was very low. Nevertheless, with Madoff and later Wasendoff, there is a set of risk factors or indicators that should be reviewed in conjunction with assessing this risk (see Figure 7-1).

Figure 7-1: Ponzi risk factor analysis

Customers and the CFTC should watch out for an aggressive sales approach, secrecy, and a high‐rolling lifestyle, not to mention investor complaints, unknown accountants, and other service providers. But such a set of indicators as these can only be a starting point for deep analysis and can by no means offer sufficient protection on its own. What can the CFTC and other regulators do to prevent such blatant fraud in the future? CFTC Commissioner Scott O'Malia, who chairs the Commission's Technology Advisory Board, was reported at an industry roundtable in 2013 as saying that it will only be through robust surveillance automation and analytics that this problem can ultimately be solved.3 To this end, he was also reported to say that while progress has been made in IT investments, he still believes much more investment is needed in data mining capabilities. In other words, while the data are there, knowing what to do with them, and specifically how to mine them to identify exceptions and patterns of bad behaviors, is yet to be solved. On this basis, it is clearly too soon to declare victory, but the increasing power of computers and the availability of artificial intelligence data analysis techniques will make this nut easier to crack in the future.

Bribery and Corruption

The temptations of bribery and corruption for some in positions of authority and influence are hard to resist, and for the snake oil salesman can lead to new business just as easily as inflating investment performance.

In the international arena, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) has long been in place to make it unlawful for US companies and companies issuing stock in the United States to make payments to foreign government officials to assist in obtaining or retaining business. In 2010, the SEC's Enforcement Division created a specialized unit to further enhance its enforcement of the FCPA. A spate of cases has resulted from that across all industries. Cases specific to banks and financial services include one involving a former Morgan Stanley employee in China in 2012, a second involving the hedge fund, Och‐Ziff in South Africa in 2016, and a third involving JPMorgan, again in China.4

Bribery and corruption is also a way to sell business in the United States. This was illustrated by the pay‐to‐play scandal, which first embroiled the New York State Retirement Fund in 2010 and resulted, amongst other things, in a guilty plea by former comptroller, Alan Hevesi.5 This was followed more recently by further allegations of corruption announced by the US attorney for the Southern District of New York in December 2016. The details this time involved Navnoor Kang, fixed‐income manager for the Fund. The lurid details include gifts of Rolex watches, free travel, and various other unsolicited benefits made by brokers, Deborah Kelly and Gregg Schonhorn, looking to place business with the Fund. This second incident occurred despite the fact that New York had instituted certain safeguards following the first scandal. CalPERS, the California pension fund, has also suffered from pay‐to‐play scandals with Fred Buenrostro, the former chief executive, pleading guilty to doing so in 2014.6

What can be done to identify such nefarious activities? What concerns us here is not so much the corruption of those in public office but the illegal methods employed by some brokers and institutions to secure business. What should be done to mitigate? First, institutions and their compliance departments need to put in place policies and procedures to guard against such activity. Education is paramount, but clearly this is not enough. Specific compliance functions must be established responsible for identifying and rooting out corrupt practices both at home and abroad. Most international banks have by now established officers and function responsible for identifying foreign corrupt practices, but similarly focused domestic functions also should be established. Second, placement agents that act as middlemen between asset managers and pension funds and the like must be subject to special attention. They are responsible for steering a very significant amount of business to pension funds.7 Are they really providing a quality service and helping pension funds to make better decisions about the asset managers they are using? Are their activities and recommendations based on legitimate and quantitative analysis? A 2015 study found that private equity funds using placement agents underperformed the market by as much as 3.5 percent annually.8 In other words, most pension funds appear not to get value from placement agents. The study also found that exclusive relationships between pension funds and placement agents lead to negative outcomes.

Lastly, managers need to be vigilant in monitoring employee activities, sudden changes in lifestyle and unexpected lavishness of dress or behavior, and their communications.

Monitoring employee communications is more important and challenging than ever. With social media, instant messaging, chat rooms, and the like, banks and brokers have multiple channels of communication. How do firms monitor all these channels? Although there are regulatory requirements for firms to monitor and capture all client‐facing employee communications, technologies have not been available to do so in a comprehensive way. One trick, for example, that such technologies must master is tracing the different IDs that employees take on across different channels of communication to a single person. For example, an identity on LinkedIn or Facebook needs to be traced back to the official firm email address. Another trick is ingesting all these communications into a single authoritative data source. Just like firms have official financial books and records, so they need official books and records for their electronic communications. It is critical when doing so to maintain the context of those communications and the chain of custody within a given conversation. Once these communications are captured, alerts can be generated for potential policy violations by the use of lexicons and advanced search capabilities to highlight conversations of interest.

Such tools are improving rapidly by arming these tools with greater language capabilities and the ability to distinguish between benign conversations and non‐benign. For example, a conversation between two colleagues discussing whether to buy tickets for the Giants game is benign. A conversation discussing whether or not to buy tickets for a client who manages the New York pension fund is not. This is another place where artificial intelligence (AI) and cognitive technologies can provide greater insight because these technologies can learn to set the first one aside to focus on the second. Normal, rule‐based software cannot do so. Although the best answer is for public officials to cut out the middleman and do the hard work of choosing the best supplier of financial services for themselves, the reality is that the middleman will continue to ply his trade and attract business in doing so. Mitigating the risk of bribery and corruption by adopting these controls and tools will continue to be required in the future.