CHAPTER 8

Building the Investment Portfolio

Key Take Aways

This chapter will guide the reader through the process of building an investment portfolio. The investment portfolio represents the translation of the pension fund's financial objectives into an investable solution for the coming period that can realistically be implemented. While investment managers and strategists may present this process as highly sophisticated, complicated, and requiring unique expertise, from the viewpoint of a trustee the process can be broken down into a limited number of steps, allowing the board to focus on the questions that matter.

This chapter discusses the nature of a good investment portfolio, what the roles of the stakeholders are in determining the portfolio, how to choose a portfolio that achieves the fund's goals, and the main assumptions to be aware of.

Creating the investment portfolio involves seven steps, the starting point being: (i) the investment objective itself, and ensuring it is clearly formulated and realizable. Next, determining the investable universe and how it is implemented and evaluated, namely: (ii) the allocation to a number of asset classes, (iii) a description of the way the asset classes should be implemented (subcategories and investment styles are determined here), and (iv) a set of benchmarks to guide implementation and provide a basis for evaluation. The next steps shape the implementation of the portfolio: (v) a rebalancing procedure between the assets is determined, (vi) a specification of the objectives for the fiduciary or investment manager is drawn up, often in the form of an outperformance target, and (vii) a risk budget determined, specifying the degrees of freedom that the investment manager has around the benchmark. The board writes down the steps in a strategic investment plan. This, in turn, forms the basis for the formal mandate that is given by the board to the investment management organization.

We will start with a brief paragraph on the question of who has ownership of which decision. This is important, because in this part of this investment process there is an intensive interaction between the board investment committee and the organization taking the responsibility for implementing the plan.

FRAMEWORK FOR THE INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO

Portfolio construction can only take place within the frame of the choices that the board has previously made. Chapter 6 discussed the investment policy statement (IPS) as an important document for trustees for shaping and directing the investment management process. Recalling the main elements of an IPS, we can distinguish those that form the framework for the investment portfolio—any portfolio should be in line with, and adhere to, the beliefs, risk appetite and strategy; and objectives that the board has established.

- Purpose, mission, strategy, objectives. The strategic mission of the investments: goals, objectives, and constraints. The fund's objectives are usually formulated in terms of required or expected return (see Chapter 3);

- Risk appetite. The level of risk tolerance and investment risk that may be incurred in realizing the return and the investment horizon required (see Chapter 4);

- Beliefs. The core investment beliefs and the resulting investment “philosophy” codify guidance as to how the portfolio will be managed1 (see Chapter 5).

If the board has not made these choices beforehand, or if these choices are only more or less implicit, then portfolio construction and implementation will lead to suboptimal results, and will generally leave a board rudderless. Without clear objectives, the board might be more interested in comparing results with other pension funds than discussing whether its own goals are being realized. Without a clear, well-thought-out and communicated risk appetite, the board is doomed to make detrimental choices during financial crises. Without a strong set of beliefs, the choice of investment styles will be based on the preferences of the asset managers and not necessarily on those of the participants.

Within the framework of strategy, objectives, risk appetite and beliefs, portfolio construction then consists of a number of well-defined steps:

- Definition and review of the investment objective. From an implementation perspective, is the objective sufficiently clear, and can it be translated into investment mandates? From a policy perspective, have circumstances changed in such a way that the objectives have to be revised?

- Number of asset classes. The asset-mix ranges of the portfolio's various asset classes.

- Implementation. The asset classes for inclusion, described at a more granular level as investment strategies and investment style(s). For example, “equities” is a broad brush. In this example, you would specify: developed market equities, United States, passive.

- Objective. A specification of the objective for the fiduciary or investment manager, often in the form of an outperformance target.

- Benchmarks. A set of benchmarks that guide the implementation and will also be used as a basis for judging the outcomes.

- Risk budget. These detail the degrees of freedom that the (fiduciary) manager has around the benchmark.

- Rebalancing. Guidelines and methodology for rebalancing the portfolio.

- Evaluation. Performance measures and benchmarks to be used in performance evaluation.

- Schedule for monitoring and evaluation. The schedule for the monitoring and review of investment performance as well as the IPS itself. The IPS should be reviewed on a regular basis to ensure that it remains consistent with the fund's circumstances. An IPS is usually reviewed every three years, with interim reviews added when material changes occur in objective, time horizon, or other fund characteristics.

The process of building the investment portfolio is usually spread out throughout the year, with three milestones that are relevant for the board:

- Milestone 1: Evaluation and exploration. A scan of the external environment is carried out to check whether the major assumptions behind the portfolio construction still hold. Any investment portfolio is based on a limited set of assumptions. For example, at the time of writing, they might be: interest rates are nudging towards a higher average rate, equities risk will be rewarded, and due to economic circumstances, default rates in the real economy remain low, suggesting a stable credit spread. The scan questions whether these assumptions still hold, and whether the board can identify new risks or developments that would dramatically alter the validity of these assumptions. In common practice, several economic scenarios are generated to challenge the current assumptions. These scenarios need not be quantitative in nature. Reading up on the literature and sharing experiences on how assets performed in stagflation, depression, or growth periods form a valuable basis for discussion. These analyses lead to a set of recommendations, for example how to reduce excessive exposure to one asset class, or when to consider adding a new asset class. The board collectively decides which recommendation to follow.

In parallel, the internal performance of the investment portfolio is evaluated. Using longer data series, trends can be identified. Investment strategies and asset classes of which the performances are below expectations are singled out. For the investment strategies, the analysis first considers the selection within the asset classes. If the poor results are attributed to this, one must ask whether the investment style still make sense, whether the drivers are still in place, and whether the manager simply is not performing or whether it is the investment style itself that is losing its rationale and attraction. On a broader level, the asset classes themselves are evaluated. Do the capital market expectations for the different asset classes still justify keeping them within the portfolio, or are new asset types becoming more attractive and should they be included in the portfolio? These analyses lead to a set of recommendations to maintain or change the number of asset classes and their form of implementation. Here too, the board ultimately decides which recommendations to follow.

- Milestone 2: Analyses. Given the new set of asset classes and investment styles, various portfolios are generated, all of which fit within the framework of the fund in terms of objectives, risk appetite and goals. The analyses therefore focus on the difference in expected return and risk compared to the current portfolio. If the difference is too small, then these portfolios are eliminated from the choice set. The remaining portfolios are scrutinized for other factors. First, does the expected improvement in return and risk outweigh the transition costs? Second, which portfolios disproportionally increase the claim on the time and resources of the board (the so-called governance budget)? Finally, the board may consider further factors. For example, do the potential portfolios improve the environmental, social and governance (ESG) goals of the fund?

- Milestone 3: Decision and implementation. The board decides on the definitive portfolio. Several options exist for doing so, depending on the board's preferences:

- Approach 1: Create a new portfolio from the ground up. Suppose the fund had the assets invested solely in cash, what would the portfolio look like if the board had the opportunity to create a new portfolio without having to consider existing assets? The board states its preferences and, based on these, the optimal portfolio is created by the investment management organization. Next, the board does take the existing portfolio into account, and works out a transition path from the current to the optimal one. Illiquid and alternative assets cannot be bought or sold easily, so the fund develops a multiyear transition path to smooth costs.

- Approach 2: Treat the existing portfolio as the best one available, unless a better alternative presents itself. The relevant potential portfolios are compared to the current one, and the board decides whether the incremental changes are worth the effort. This makes for a straightforward and expeditious decision process: the board should state its preferences beforehand, i.e. which factors it considers most important, and a preferred portfolio can then be agreed upon. But there are a few pitfalls to consider. First, the focus is on incremental differences. The current portfolio serves as the baseline, and it is easy to forget to take a critical look at the baseline itself: are viable alternatives being ignored because we are too comfortable with the choices in the current portfolio? In line with this, the board is naturally inclined to prefer and choose the asset allocation it is familiar with. Adding a new asset category has a big obstacle to overcome, namely, the attitude dictating that if the current mix works fine, there is no need to change it.

- Approach 3: Blind-test new portfolios. The third approach overcomes several behavioral pitfalls, increasing objectivity. Why not make the possible portfolios anonymous, not listing the assets, but only the expected return, risk and other key measures? In this approach, the staff develops a number of portfolios that all fit within the framework of the fund in terms of objectives, risk appetite and goals. The discussion is then framed in an alternative way: should we, given the current cover ratio and expected financial environment, choose a portfolio with more or less investment risk? And zooming in on investment risk, should we choose a portfolio with less volatility in normal periods but more shortfalls in extreme periods, or vice versa? Once the number of portfolios is narrowed down by this discussion, the underlying asset allocation is shown, allowing the board to consider implementation issues (costs, complexity) before making the final decision. The main advantage of this strategy is that the decisions are based on a relevant measure: the amount of investment. Preferences and decisions are not biased due to personal likes or dislikes in terms of asset classes. However, it requires a board that knows how to interpret statistical measures such as volatility. Chapter 4 argued that this is a challenge, even for seasoned trustees. Such approaches need to be well prepared in advance.

Whichever approach the board chooses to determine the portfolio, it is best for it to discuss the choice in advance, including identifying pitfalls and suggesting measures to avoid them. Finally, the board decides on the definitive portfolio, adding the requirement of assurances that implementation will be consistent, and that potential return/risk losses due to an implementation gap will be mitigated. This is then written down in the IPS, which can be used to amend the mandate for the investment management organization.

THE BOARD'S ROLE IN PORTFOLIO CONSTRUCTION

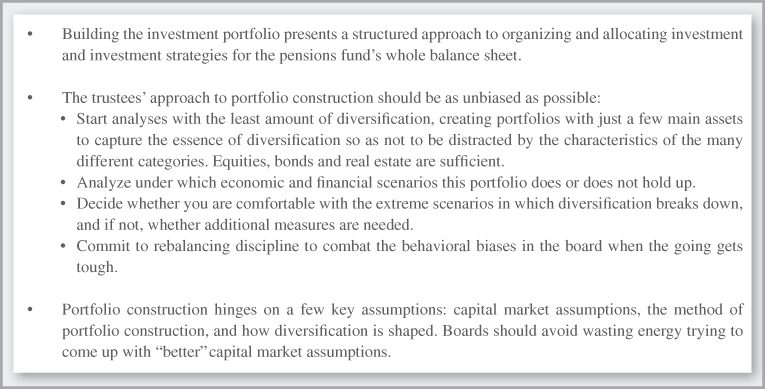

The board is responsible for developing the investment policy. The task for the board is to maintain an overview of the different steps, how they interact, and what the role of the board members should be. Board members can easily succumb to the temptation of forming pet theories about asset classes, interest rates, or investment opportunities. It may be true to say that this shows involvement in the subjects that the board has to deal with. But it is not the role of a board to outsmart the financial analysts or investment strategists. What the board can do, however, is challenge their assumptions to test the robustness of the analysis and subsequent recommendations. Below we again review the steps in the IPS, but now with the addition of the specific question: what is the focus for the trustee? Exhibit 8.1 below shows the factors on which the framework of the investment portfolio rests, along with the focus for the trustees.

EXHIBIT 8.1 Framework for the investment portfolio and the board's focus.

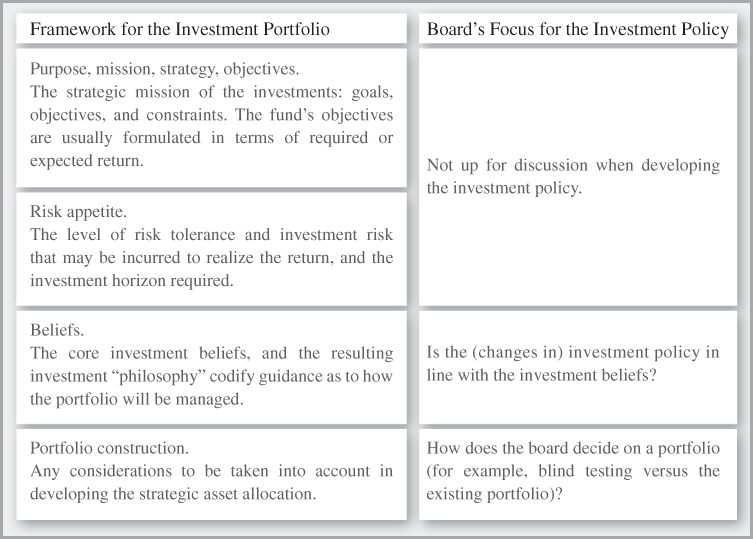

Building an investment portfolio requires some decisions and steps. What these steps are and what the focus for the trustee should be are shown in Exhibit 8.2.

EXHIBIT 8.2 Building the investment portfolio and the board's focus.

What Is a Good Investment Portfolio?

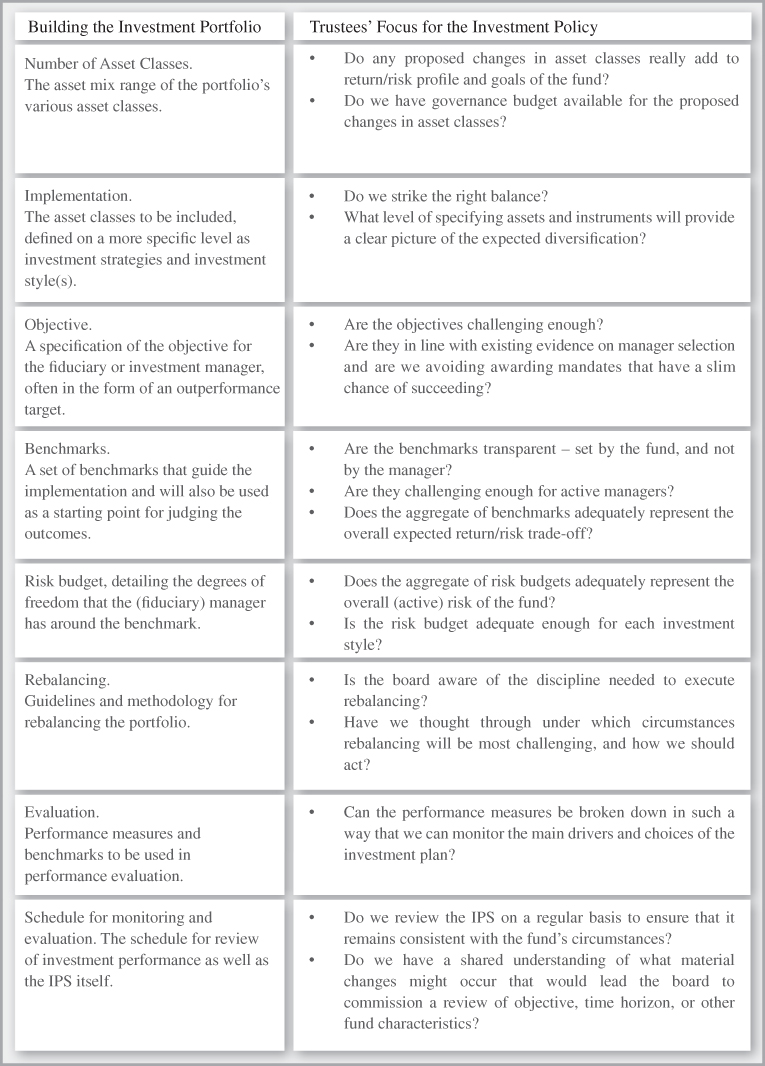

A board of trustees is responsible for developing an investment plan that is the best possible option for realizing the fund's goals, given constraints on the amount of risk, horizon, liquidity, and any other constraints. The previous discussion has focused on the steps needed for portfolio construction, which run the risk of overshadowing the real purpose of the process for a board. What exactly, then, is the best possible investment portfolio? We provide you with a list of criteria (also shown in Exhibit 8.3) for judging the quality of a portfolio and for comparing, scoring, or ranking the quality of different portfolios.

EXHIBIT 8.3 Criteria for scoring the quality of a portfolio.

A good portfolio will help the board:

- Realize the primary investment objective over the relevant horizon with a high level of probability (fit for purpose). Is there a high level of probability that the portfolio will realize the primary investment objective over the relevant horizon? Is it fit for purpose? If this is not the case, it is time to rethink either the objective or the portfolio. This, for example, led the Norwegian Fund to increase its equity exposure in order to generate the long-term returns it targets.

- Realize potential secondary objectives such as environmental, societal, or governance goals (sustainable). There may or may not be other investment objectives. For example, the South African pension fund Government Employees Pension Fund (GEPF) has the dual objective of realizing return as well as contributing to the economic growth of the local economy.

- Do all of this at the lowest possible initial investment (effective). Is the return as high as possible within the set risk appetite; is the risk budget fully utilized? If the risk budget is not fully utilized, the fund might be setting an ineffective premium rate, i.e. charging a higher amount than necessary.

- Be robust in as many circumstances as possible (robust). Will the portfolio be robust in different economic and financial scenarios? Many risk premiums simply need time to be earned. It does not make sense to have an investment plan with a high allocation to equities, requiring a long period to earn the premiums, and then change the asset allocation in just a few years. So from the start, the number of assets and resulting asset allocation in the investment plan should be based not on one, but on a number of different scenarios.

- Have as much flexibility as possible for adapting when needed (flexible). Is the investment plan flexible over a relatively short term? If an investment plan advises changes in equities and bonds, these are usually easily implementable within a few months. But if a large part of the plan is based on shifts to illiquid assets over a longer period, then the board really needs to discuss how to commit itself to such future investment plans.

- Be based on a shared understanding of the drivers (acceptable). Is the investment plan clear about the main drivers and choices in the investment plan? What are the risk premiums, the amount of risk that is accepted to earn those premiums, the investment styles, and the horizon? If the board does not have a shared understanding of the main drivers, new board and committee members will challenge and rethink these drivers over and over again, especially in case of disappointing results. This reduces the horizon of the investment plan considerably.

- Involve the lowest possible cost (cost effective). Costs (meaning all costs, visible and less invisible) are always hotly debated. One school of thought argues that it is the net result that counts. Another school argues that costs are a factor that can be managed, and you should always work on cost efficiency because higher-than-necessary cost could be considered misspending the participants' premiums. This is the school we are in. There is quite a lot of evidence to substantiate the view that managing for lower cost is one of the most effective ways to increase the long-term return.2

- Have the continued support of the board and any other critical stakeholders to stay the course when things don't work out as planned in the short term (supported). Will the board uphold the investment plan even when things go sour? Suppose there is a period of financial turmoil: diversification between equities and bonds will probably work (equities go down, bonds go up) but all the other assets will move more or less in the same direction—downwards. In other words, every now and then, in practice, the quantitative assumptions about correlation, diversification and investment styles fail. Would a board still consider the investment plan to be robust, even if these assumptions fail?

- Be set out in the most transparent, most understandable, and most controlled way possible (controllable). Is the board able to monitor the main choices in the investment plan? The drivers of the investment plan should be attributable and visible in monitoring and reporting. If the potential success of the investment plan hinges on the credit spread and this is not reported, trustees cannot monitor or evaluate their own choices.

- Take the simplest, most elegant form in the most transparent, most understandable, and most controlled way possible (“parsimonious and elegant”). Is the portfolio as simple as possible, given the objective? Can it be made simpler? Often, complexity comes at a great cost, reducing transparency, oversight and understanding. Ceteris paribus, simple is better than complex.

When actually scoring the quality of a portfolio, it is a good idea to assign a weight to each of the criteria, thus helping the board to develop the portfolio that best meets its expectations, as well as providing a framework for a disciplined evaluation of it. For example, for some boards the ease of controlling a portfolio may have a high weighting, whereas other boards might give maximum weight to realizing the primary investment objective.

Among the criteria, there are definitely a lot of trade-offs that a board must consider. For example, trustees might expect to be able to generate another 0.5% annual expected returns at the “cost” of carrying out a number of complex and hard-to-control investments.

CAPITAL MARKET ASSUMPTIONS

Boards are not in the business of predicting financial markets or economies. Yet portfolio construction hinges largely on a small set of assumptions, particularly capital market expectations. Questions ensue such as “What will we earn on equities in the coming period, and is it enough to compensate for the investment risk that we have to incur? And what will interest rates do?” These questions are at the core of the fundamental assumption in financial theory on the trade-off between risk and return (see Chapter 4). Capital Market Assumptions (CMAs) are used by investors and advisors around the world to guide their strategic asset allocation and set realistic risk and return expectations over different time frames. These assumptions help investors formulate solutions aligned with their specific investment needs. They cover expected (excess) return, risk, and correlation over different horizons. A coherent set of CMAs is an economic scenario. It is crucial to generate different scenarios that challenge the achievement of the goals or force trustees to think of the unthinkable.

Determining the CMAs for a broad group of asset classes thus involves analyzing the interaction of risk, return, and correlation. In order to capture these interactions, we use what economists call an “equilibrium model.” Equilibrium describes a situation in which all expected asset returns are a fair reflection of their risk and correlations and does not refer to any specific time horizon. What it means in practice is that for asset classes that are reasonably correlated with one another, expected returns in excess of cash are approximately proportional to risk, but for asset classes that exhibit low correlations, expected returns can be a bit lower than from the proportional application of risk.

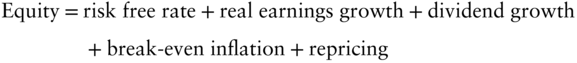

CMAs can be developed in different ways. The most frequently used approach is to break the CMA down into different components. For example:3

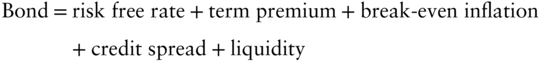

Similarly, a bond is broken down into its components:

Capital market expectations may seem like a pretty objective exercise, but we should not be fooled. If we estimate the expected risk-free rate and the term premium, we are building up insights into expected returns. However, we also know that the level, or level of change, of the risk-free rate is correlated to the level, or level of change, of the term premium. Developing CMAs requires an intertwined choice: determining the economic and financial scenario on which the CMA is based, and the horizon that is required. Estimation with a high risk-free rate and low term premium is historically consistent with a period in which central banks have been active in raising interest rates to slow down expected inflation.

Diversification

Diversification is a much-used term within pension funds. Two questions are of importance for trustees. First, do the trustees share the same notion as to what diversification means for the fund? Secondly, do the assets chosen for diversification stand the test of time, are some of them perhaps only temporarily attractive, or are they truly new and do they diversify risk premiums?

Pension funds are clearly fond of diversification. Since 2002, they have ventured into credits, emerging markets equity, infrastructure, hedge funds, and private equity, while in recent years factor investing or impact investments have experienced an upswing in investment portfolios. Diversification, discussed in Chapter 4, can have different meanings to different people. Trustees should raise the question of which purpose or combination of purposes is relevant to their fund, as each approach leads to a different portfolio:

- Diversify to reduce overall portfolio risk. Whenever two imperfectly correlated assets are placed in a portfolio, there is an opportunity to earn a greater return at the same risk, or earn the same return at a lower risk. The correlation between the new asset and the assets in the portfolio should reflect a sufficiently different pattern of returns; and the allocation of the new asset should be sizeable enough to matter.

- Diversify to hedge against adverse asset pricing shocks. If there are extreme price movements in the financial markets, will the new asset's lack of correlation disappear and is diversification then be suspended? Or does the new asset provide a really new, independent economic source of return that is ex-ante unlikely to move in step with the other assets? This seems like a simple question, but it is actually hard to answer. For example, research shows that country equity markets offer less diversification in times of falling markets than in times of rising markets. The same is true for global industry returns, individual stocks, hedge fund returns, international bonds, etc. Similarly, international diversification seems to work during good times, when it is least needed, but to disappear during falling markets, when it is most needed. Maybe the only light beacon here is that asset correlation within countries decreases during periods of market turbulence.4

- Diversify to achieve high absolute and risk-adjusted returns. Is the new combination of assets able to increase outcome relative to the major asset classes in the portfolio? The appropriate measure to use is the Sharpe ratio, measuring the excess return above the risk-free rate per unit of risk.5

- Diversify to hedge against unexpected inflation or deflation. Conventional wisdom has held that assets such as real estate and long-term bonds hedge against inflation. However, with the exception of inflation-linked bonds, many assets have a complicated relationship with inflation. Inflation elicits differing responses; real estate contracts can have a standard clause in which rents are corrected for inflation, creating an adequate inflation hedge. Many assets by definition provide a partial inflation hedge; inflation may raise future cash flows, but this is partially offset, as inflation also raises the nominal interest rate to discount the cash flows, eroding the overall valuation. In addition, the fact that there is a historical correlation with inflation is not sufficient reason to extrapolate into the future. Unforeseen consequences can always affect the future. For example, thanks to the enormous success of Wal-Mart, few retail chains were able to pass on increased inflation to customers; Wal-Mart alone is credited with reducing inflation in the United States by one percentage point per year in the 1990s.6

- Reflect the overall investment universe. A portfolio with 50% equities and 50% bonds might be called a balanced portfolio, but it is definitely not a reflection of the investment universe. This implies—in theory—that any portfolio that does not include private equity for example is making an implicit bet that a portfolio without private equity yields better returns.

- Diversify to deliver a stable stream of cash flows to the investor. Pension funds are greatly concerned with liquidity, a major concern being the creation of a stream of cash flows that to a large degree offsets the pension payments to be made. Investments with strong cash flows provide a natural hedge against pension liabilities, which are basically a set of guaranteed future cash payouts.

- Diversify to capture the underlying economic and financial factors that drive asset returns. Taking a quantitative approach, equities or bonds are not viewed as issued by companies, but rather as representing a bundle of risk factors. According to this view, “decomposing” these assets into risk factors allows the investor to diversify far more effectively.

How many assets are needed for diversification? Having come to a common understanding of diversification, do the assets chosen for diversification stand the test of time, should the set be expanded, or are just a few assets sufficient for effective diversification? In allocating the assets, regulators expect the trustee to diversify the holdings and to exercise prudence. In other words, trustees should not bet the house on anything too risky in the portfolio.7 However, views on diversification have changed dramatically in the past decades. Pension funds in the 1970s were content with bonds and real estate, assets that were considered to be “safe.” But returns were low, so funds progressively moved into equities, commercial property, foreign securities, and derivatives. New technology made this possible. In the 1990s, the pension fund industry experienced a makeover when the combination of Asset Liability Management (ALM) techniques, deregulation, and portfolio optimization approaches gained ground, widening the scope of assets to invest in. The risks were higher, but so were the rewards. Additionally, higher returns brought down the relative costs of running the fund.

In hindsight, it appears that only a limited number of strategies break through and help to diversify effectively. In other words, trustees should quiz their investment managers and advisors critically, because introducing new strategies does not necessarily achieve diversification. Alternative investment strategies have suffered from two problems. First, the success of many new strategies was boosted by the same factors: low interest rates and robust economic growth. This, in turn, encouraged investors to use leverage to enhance returns. Some alternative investments share more factors; private equity gives investors exposure to the same kind of risk as publicly quoted equity, albeit with added leverage. When prospects deteriorated, investors were forced to sell all those asset classes simultaneously. Secondly, some of the asset classes are rather small. This illiquidity is attractive since it offers higher returns. As more investors get involved, the market becomes more liquid, and the higher return is eroded. However, when everyone tries to sell, illiquidity rears its ugly head again—there are no buyers to be found and prices tumble. This is very unpleasant when pension funds have to value their investment at market value. Still, investment managers increasingly look to add new—alternative—investments to bolster diversification advantages,8 which can mitigate these risks to a large extent. However, there is no point in adding new strategies if the investment does not offer a genuinely different source of return, or if the asset is already overvalued. In other words, the bar for new investments to count as a true “diversifier” has been raised substantially, and if these investments are true diversifiers, their relative size in the investment portfolio will be limited.

Along with the search for alternative investments as a source of diversification, factor investing has gained traction, viewed by some as a replacement for the current approach to diversification. Interest in factor investing started with the Ang, Goetzmann and Schaeffer study,9 commissioned to investigate why active returns of the Norwegian Fund were disappointing. A major finding was that a large share of active returns could be attributed to systematic factors; five years later, major pension funds such as the Alaska Endowment Fund, the Dutch PFZW or the Danish Arbejdsmarkedets TillægsPension (ATP) all implemented a form of factor investing. From the outset, it seemed like a sensible development. Asset returns can be attributed to a few distinct underlying factors such as macroeconomic factors, firm attributes or style factors, with these factors representing sources of systematic risk and return. This approach aims at providing a relatively precisely defined exposure to factors that may explain differences in asset returns and, to a large degree, the excess returns of actively managed portfolios. The factor approach creates the opportunity to construct portfolios with asset selection based on the knowledge of underlying factors, or even design portfolios using factors rather than assets.10 Within this factor framework, which is rooted in the Asset Pricing Theory (APT) developed in the late 1970s, any asset can be viewed as a bundle of factors that reflect different risks and rewards. Therefore, it makes perfect sense to focus on these factors, allowing investors to identify them and understand what really drives asset returns. These insights help to develop portfolios that realize the required risk profile not only before, but also during, volatile periods.

Rebalancing

Rebalancing is regarded as a technical component of implementing an investment portfolio plan, where portfolio weights are adjusted in line with the risk appetite of the fund. This policy details when and how the policy portfolio is adjusted in line with changes in the cover ratio or financial markets, how to adjust the assets to the weights of the strategic benchmark portfolio, and whether the rebalancing is done on a frequent regular basis or based on specific triggers.

Rebalancing on the basis of constant policy weights represents one possibility. At the other extreme, the fund can have a solvency program in place, which adjusts the level of policy weights depending on the amount of downside risk the fund is willing to accept given the funding ratio and financial market volatility. Similarly, the solvency program adjusts the level of policy weights depending on how close the fund is to achieving its long-term goals. Sometimes, funds allocate part of the bandwidth around policy weights to TAA (tactical asset allocation), which involves making short-term adjustments to asset-class weights based on short-term expected relative performance among asset classes. The assumption is that investors can take into account short-term opportunities with the aim of achieving the best performance for the portfolio, bearing in mind the level of risk defined.

At times, a portfolio's actual asset allocation may purposefully and temporarily differ from the strategic asset allocation. For example, the asset allocation might change to reflect a pension fund's current circumstances when these are different from normal. The temporary allocation may remain in place until circumstances return to those described in the investment policy and reflected in the strategic asset allocation. If the changed circumstances become permanent, the manager must update the investor's IPS, and the temporary asset allocation plan will effectively become the new strategic asset allocation. TAA also results in divergence from the strategic asset allocation, and responds to changes in short-term capital market expectations rather than to investor circumstances.