CHAPTER 13

Releasing the Potential of the Rising Generation: How to Develop Capable Successors

One quality that showed up in almost every generative family is a deep, ongoing, active engagement in developing the skills and commitment of their rising generations. They realize that these young people are their most important resource, and they will not spontaneously grow up to become good stewards. They have an important, impactful, and unique opportunity in the family enterprise, but to make good use of it requires engagement, investment, and active measures. Family elders realize that wealth can have negative impact on their offspring, and so they thoughtfully invest in many programs and practices. This chapter begins with the challenges facing wealthy young people in general, and then looks at how parents, and collective generative families, develop capable, committed stewards for their enterprise.

Every family, wealthy or not, faces the daunting challenge of raising children to become productive members of society. But following the adage “to whom much is given, much is expected,” an extraordinarily wealthy family with many shared assets faces additional challenges. Since young members of such a family expect to become responsible for a large and complex set of financial and business entities, they have to learn skills that the less fortunate never encounter. They also need to learn and accept the family's values about work, responsible behavior, lifestyle, money, inheritance, and social responsibility.

Generative families educate and prepare the next generation to take care of their assets as well as use the freedom and opportunities they have been given to make a vital contribution. No family wants to feel that it created great wealth so that its children could be lazy, wasteful, and unproductive, spending the money as fast as possible. Generative families want to develop character in young family members, and they want to see it develop without coercion. We look here at how actively and explicitly this is done.

They view a responsible inheritor as having the following qualities:

- Working at a productive career or life task valued by others that they care about and have become skilled at

- An informed owner (or owner-to-be) of the family assets

- A good family citizen who is committed to family values and participates in family governance

Meeting this challenge involves more than having good intentions or designing a trust with restrictive spending rules. Generative families adopt family development practices that can be even more time- and energy-intensive and demanding than creating a successful business. That may be why there are so few of these families.

Financial and business success enables new paths to open for the rising generations. Elder generations take a long-term view of the future, an essential element of which is preparing their children and heirs for a good life. This has always been a concern of wealthy families, as US founding father John Adams affirmed in this letter to his wife:

I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.1

This letter highlights the fact that members of the elder generation may envision a very different future for their children than simply continuing the legacy business. They see their family success as offering wider opportunities for their children, ones that are not open to everyone.

But with infinite possibilities ahead of them, their children may find it difficult to decide what to choose. In addition to skills, they need to discover life purpose and develop their own values for living that build on the family's legacy values. Every generation of parents would like to be able to control the positive effect of their wealth on their children. In reality, control is limited, and parents can only hope to influence, set an example, and talk together with their children about the future. This final section looks at how generative families develop activities to set this positive climate for their rising generation. Each time a new generation takes leadership, they demonstrate how well they have succeeded at this goal.

One of the core findings of this study is that a generative family is focused on creating opportunities for and encouraging the development of its children through active investment of family resources to develop skill and commitment. One third-generation family leader reflects:

You have to take the time to develop each member to their potential. People don't understand how important education is, and underestimate the time, the care, and the devotion that it takes to build a strong family. But for me that's where everything happens. So that's where we spent most of our time. If you look at our family business, it would be a combination of individuation and collectivism.

An Asian family leader explains the many facets of this “project”:

The important matters are entry of a generation, what we expect heirs to do, values we wish for the parents to instill in their kids, the role of the family in matters, and the access to the foundation programs. If they want to get involved, we have summer jobs where the kids get a bird's-eye view, whether they're in high school or grade school. We have community projects; we send some of our kids to do hospital work or Habitat for Humanity. We give them a flavor of the business stuff that we think is important.

Generative families mention several reasons for developing the next generation:

- To have their successors sustain and oversee family assets to use them wisely while being stewards for the next generation.

- To use family resources to develop the potential and capability of each individual.

- To develop and install a cadre of successors to carry on the family legacy of profitable and productive ventures, following the family's espoused values.

Families without a legacy business or substantial shared assets handle the tasks of raising productive offspring privately, within the nuclear family, preparing them to go their own way in life. The same is true for generative families—with an additional wrinkle: given their shared resources, generative families need responsible and competent family members to steward these resources in future generations. Therefore, they must teach additional skills and instill sensitivity in their successors as stewards of the family wealth or risk losing that wealth through inattention or incompetence. The financial skills they need to learn are far more complex than budgeting or balancing a checkbook. For this reason, they often provide this education as a collective family activity.

Many generative families also feel that the primary responsibility for this development belongs in each individual household. As one leader observes, “Our different families have different perspectives on how much information people should be provided with and in terms of the attitudes toward money and spending and what kids should have or not have. And so those kinds of things are left much more to the individual families or branches.” The extended family then builds on the foundation of values and character with shared family activities agreed to by everyone, designed to add specific skills and commitment to the family ventures.

My colleague Jim Grubman and I2 previously described the journey of a family new to wealth. Wealth creators usually come from modest circumstances and are new immigrants to the experience and use of wealth. As we saw in Chapter 4, they are self-made and remember what it took to achieve their wealth—hard work, individual initiative, personal drive, and high control.

Their children and grandchildren are born into an environment of family affluence. They are natives to family wealth; wealth is always part of their lives, and they grow up in a world of wealth that conditions their everyday reality. But they are also aware that they did not create this wealth. Lacking awareness of where it came from, they often have anxiety about what they would do if it were not there. They hear from their parents that they should be prepared to go their own way, but because they have grown up in an affluent household, what this actually means may be more theoretical than realistic. What they experience is anxiety, rather than direction.

When parents look ahead to what they want their children to learn, they tend to emphasize skills of independent action that served them well. Their children must learn self-reliance and be able to create their lives on their own. Parental intention is admirable, but parents' knowledge of next generation needs is incomplete. In addition to learning how to find their way in their career and personal relationships, young family members of generative families need to learn about additional areas related to their family assets and wealth.

Because their family is linked by trusts and shared financial entities, they must learn skills to oversee and manage these assets and learn how to work together in harmony with siblings, cousins, and spouses. Inheriting wealth does not mean a person has the ability to use it wisely. Careful use of wealth must be learned. Younger members of the family need collaborative and team-oriented skills to oversee, steward, and add to the family capital. They must learn what it means to become a responsible family steward, and work together to achieve it.

The Developmental Path of the Young Family Member

Inheriting Wealth: What Is Its Intended Purpose?

“It's all about the money,” one family leader observes. While this view is held by many family elders, generative families for the most part view this notion as limited and short-sighted. Although money looms large in the life choices of a next-generation family member, continuity depends as well on developing all forms of family capital. Money alone is not a strong enough glue to compel family members to dedicate themselves to each other. They need a compelling purpose to pull themselves from their individual lives to commit to the family enterprise.

Financial rewards are not just for immediate enjoyment but are also to be sustained for future generations and used for values-based endeavors. Family members must develop a balance between current and future needs and between consumption and service.

By remaining united across generations and reinvesting profits, the family enterprise can remain large and profitable. Wealth is not a goal in itself. Its value lies in what it allows individuals and the family to do and in how it is used. This is something that the family determines together. At some point, often at the initiative of the emerging generation, the family begins to ask each other what all this family wealth is to be used for.

This young successor in a hundred-year-old South Asian family with 450 family members observes:

The first eighty years were basically surviving and building up wealth; we reached the point where we're doing very well—more cash flow, higher dividends. With more wealth, there could be a change in behavior with the way the younger generation deals with it, so we have to be very conscious about how this wealth is deployed and how we manage to keep our values in the midst of all of this seeming success.

With the growing family infrastructure of shared activities and practices, a young person growing up in a wealthy household can't help but wonder about the family wealth. Young people in such families wonder about:

- What they can expect in their lives

- The rules for using and benefiting from the family resources

- What the family enterprise contains and how it works

- Roles they might look forward to in the business and family

- What they have to do to attain them

The family can constructively engage this curiosity and offer answers so that its young heirs can move forward with their lives and make thoughtful and relevant decisions.

Family wealth, as noted in Chapter 2, also includes human, relationship, social, and spiritual “capital.” These forms of capital can endure longer than the original financial wealth. In addition, developing non-financial capital adds meaning and shared purpose to the family.

One of the most important practices for a generative family to develop and affirm values and purposes for its various family ventures and its wealth. The family struggles with the question “What is our financial wealth for?' in a way that engages the members of the rising generation. The presence of shared values and mission is necessary so that the family, with new members entering regularly by birth and marriage, agrees with or modifies what it is doing together.

With so many family members, the expectation of living a life of ease may no longer be realistic. But the children should not be the last to learn this. Aside from a very few (but highly visible) members of the global leisure class, fourth- or fifth-generation family heirs can look forward to a nice “lifestyle supplement” to their income, enabling them, for example, to work for a lower salary in a rewarding career but not enough not to work at all:

Family wealth enabled me to live comfortably and put my kids through college. My kids definitely see it in the same way. My son owns his own business. I have given him a lot of support, but he knows it comes from our family business. The family definitely sees that. And that is our success. Not only that, but the family stories are continuing.

Young children growing up in a wealthy environment cannot be expected to understand these limits; the family has to help them overcome unrealistic underestimates or overestimates of family financial wealth. These children may not respond well to an ultimatum. They need warning and active guidance from their parents to prepare them for their future role as stewards.

Families have different ways of distributing wealth. Each approach deeply influences the mindset, motivation, and development of the rising generation. Traditional cultures, spanning regions such as southern Europe, the Middle East, and South America, offer an allowance or regular distribution to each family member, usually allocated by age. Only a handful of the legacy families in this study operated this way, and they all reported finding this approach counterproductive. When income is not connected to ownership or family engagement, its presence gives the message that there is nothing the rising generation needs to do to qualify for it. It makes family organization more difficult. The majority of generative families pass inheritance to individual households, even if it is owned by a trust; each household or family branch allocates inheritance in its own way. One legacy family can therefore have several approaches to inheritance.

G1 wealth creators usually create a complex set of financial structures—trusts, holding companies, and a foundation—which form the reality for each successive generation. As one sociological researcher observes:

In generational aging and transition, a family must create a transcendent, controlling version of itself in the organization of its property to achieve a coherence of organization that can preserve the mystique of its name and ensure its continuing exercise of patrician functions in its social environment. This coherence does not come as much from commitments made by its members to their common lineage, as from the application of law and the work of fiduciaries whose primary responsibility is to protect the founder's legacy from divisive family quarrels.3

These arrangements can be seen on a continuum of tighter to looser control. On one end are purpose trusts that use resources only in clearly defined ways. In the middle are pools that can be accessed, with rules and limits and often a nonfamily trustee. Then there are inheritances that are more loosely controlled but with voting control of the asset assigned to a single family leader. And finally, there is no control, where the family owners are free to decide together how to use their wealth. Each family must teach and come to terms with the degrees of freedom handed over to the new generation.

Between the heir and the family wealth, then, lie trusts and financial entities, as well as family advisors, all of which inheritors must understand, accept, navigate, and eventually oversee. Learning about this legal structure, young people can feel devalued or distrusted if, for example, they are offered a beneficiary role with limited power or influence. The successful family must provide the training to make this relationship harmonious and satisfying and may also look for ways to allow more flexibility. Each young family member must understand these options and learn how to relate to them in a mutually beneficial manner that may not be immediately clear. By understanding, negotiating, and engaging, these young family members may discover areas of flexibility not initially apparent. To avoid acrimony and conflict, the family must develop caring relationships and commitment to work together so that the family wealth serves the family goals.4

Parenting and Developing Character in the Wealthy Household

The primary responsibility of parents is to raise productive adults. If the family is also an economic unit, the family usually prepares its children to fulfill their responsibilities in the family ventures. Generative families report that this task is made more difficult when the family has substantial wealth. Wealth can be seductive; it deeply affects the reality of how children grow up and how they learn that the wealth is not just something to make them special and comfortable. The family has to teach values about children's responsibility to be stewards of the wealth, ensuring it will be wisely used.

An added challenge is that wealthy children grow up with a sense of specialness that sometimes translates into feeling that wealth makes them better than other people. This is called entitlement; its opposite, a sense of service and responsibility to sustain the wealth and add to it, is called stewardship. The goal of the privileged household is to help its children move from entitlement to stewardship. This chapter explores two facets of this endeavor: first, the active role of parents before their children begin university, and second, the journey of the young adult to develop a personal identity. The first stage is the prime time for active family engagement, teaching, and learning; this time is followed by a period of gradually letting go as young adults find their way through higher education and into their first work experiences.

Parents set examples about values and teach responsibility even when they are not conscious they are doing so. “Messages” are passed in family conversations about what is and is not important about wealth and in life. For example, one young woman proudly showed her father her first paycheck, earned from working in a service project. Her father's response was, “Why are you working? You don't have to work.” The effect of this message was that she always felt vaguely guilty about working because she was taking money away from people who needed it.

Most generative families report that they are successful in sending the message to many, if not most, of their rising generations that they must develop a work ethic, and an ability to take care of themselves if the “golden goose” stops producing:

We are focusing on what the family members want to do. We're encouraging the family members, by saying clearly, “Look, you're getting a check from the business and if you don't want to be in the business, it's fine. But go do something. Learn what you want to do and pursue it.” That way they learn the skills of how to survive because we don't know what happens if the wealth supply runs out.

Young people develop values from their parents' indirect messages and examples. They may learn that a person's worth is measured by how much money they have or that people who have money do or do not do certain things. These messages can be conscious or unconscious.

Money has many meanings for a young person. Children are especially curious about where money comes from, as it is very abstract and almost magical. They have to learn that some people do not have nice houses and schools. Their experience may be that when you want money, you just stop at an ATM and get some. Parents may use money as a reward or give children gifts when they leave for work or a vacation on their own, leaving their children to learn that money can be a barely adequate substitute for love and engagement.

Values about wealth, the families in this study report, arise from engagement and example within the family, rather than policies and rules. Here is an account by a South American family of how one parent influenced his children:

I raised my children to be leaders and live by the family values. We started working with the children when they were very young. We went with them to sports activities, and every single day of my life, I talked to every single child. Every night, we'd have a little chat. Two very important things came out. One was the ability to communicate. We have excellent communication skills among ourselves. Communication didn't start when they started in the business. It started when they were four or five at the breakfast table or basketball court. We try to have dinner together every night. Every Sunday, we would go to church. I think that strengthened family values. My wife is great. She's the chief emotional officer. When you give people security and enough love to go around and respect them, they are secure. When people are anxious or nervous or worried, they are that way because they're not given enough love.

Those values were transmitted to the children. My wife and I insisted on excellence in education. I guess if we had had a child that didn't want to study, we would have had to force them. But we really tried to mold them to do well in school. They went to the best schools here, but every summer we sent them to the US for summer programs. Since my grandfather never had an opportunity to have a good education, he used to tell me, “I told your father that I'm not going to give him that inheritance from me. The only thing I'm going to leave him and your uncles and aunts is an education. That's the only inheritance that no one can take away from you.” That was a very nice message.

He helped his children see that despite living in a highly affluent community, they would not have everything other kids had. While they were richer than most of their peer families, his children were taught to be thoughtful about their spending.

Young children learn about work by doing chores and helping around the house. If there is a family business or family office, they may experience work by helping there. This may also be the first time they get paid. By visiting the family business and seeing how work is done, they directly view the source of the family legacy and imagine their own possible future. Similarly, if a family engages together in community service work, children learn about other cultures and the challenges of a world where some have and others do not. This is a difficult moral lesson.

“We know what a drug money can be as it stopped children from becoming the best they could be. I didn't want that for our children,” says a matriarch of one branch of a large multigeneration family. “I was very conscious that I wanted my children to make it on their own.” This desire in turn led her and her husband to work actively with their own family branch, developing a strong family organization to introduce a contrasting culture of excellence for their children.

Sharing family values and discussion about money and wealth is a critical task for a wealthy family. One South American family heir reports how the family established a “counterculture” that challenged the prevailing materialism seen in their peers, a difficult lesson for them to learn:

I noticed a lot of children are given polo lessons, yachts, sports cars very early. We have stayed away from that. The first car they got was a Volvo. No yachts, no polo. It's about work and helping your neighbor, loving your family. When our friends at school would get something like a fancy new bike, my mother would say, “Well, that's not necessary. You can have a simple bicycle. It will do the same thing.” They never tried to match up to the advantages of other people. So if somebody had a car, we had a bicycle. Or if somebody had Nike, we had Converse. In that sense, money was not important. It was never discussed until we were older. We learned to be moderate with money, have control over it. Don't overextend yourself.

I remember I had a savings box made out of paper-mâché. Every day, they gave us seventy-five cents or a dollar to buy a coke or candy. I never bought the coke or candy. I saved the money and put it in my savings box every day for I don't know how many years. I saved almost $2,000 like that. Then I bought stocks. I was about fourteen or fifteen, and I said to my dad, “Why don't you buy some stocks for me?” So he bought me some stock that I still have. I also collected auto stickers and sold them at school. With that money, I bought a croquet game with my neighbors, and we formed a croquet league.

One challenge of long-standing family wealth is a by-product of its success. Over generations, the family establishes a public image of values and service to the community as well as a vibrant and successful business. The outside view is of prosperity and service. The next-generation family members benefit from this perception by experiencing respect and community status but also sometimes envy and jealousy.

Young family members may need help to respond to this public perception:

In terms of values, I keep stressing why we want to stay together. Very few people in my family have anybody to relate to with this wealth other than ourselves. We're not the Rockefellers. We all live with the fact that people assume that we have private jets and live this grand life, which we don't. But we're much better off than most of our friends, so we're very fortunate. Nobody wants to complain about having money or the issues that come with it, so there is a big void of how you discuss this or who you discuss it with. By getting together, we earn a comfort zone that we can talk about it. We need to rely on each other that way. Share experiences, thoughts. How do we deal with that as it goes to our kids? We all are guinea pigs.

While the “family” is wealthy, individual members may have no control over or access to that wealth. The outside community may regard them as rich, but as individuals they feel constrained and of limited means. This may make them anxious and uncomfortable. How do they react when someone asks for a loan or expects them to always pick up the check at dinner? Several heirs mentioned the importance of not having their family wealth known to their peers; one family member changed his name when he entered college so that he would not be associated with his parents' generous endowments.

Families all over the world share one quality in relation to wealth: they don't talk about it or do so with great difficulty. Many generative families experienced the distrust and incapacity that came from keeping it secret from their children. They came to learn (often after a struggle) how to talk with their children about money, wealth, and inheritance. Rarely does a family do this from the start. A second- or third-generation leader, nonfamily leader, or advisor can guide the family to this conversation. One family in this study had difficulty with its first attempt at a family discussion. But the family tried again and was more successful.

If the family does not allow the children to talk about money and wealth, the children's feelings and struggle will have no outlet, and they may make self-defeating life choices. Several family members talked about feeling a vague sense of guilt about having money. “I didn't earn it,” said one family member, “so I didn't feel it was really mine.” While family wealth provides many benefits, members of wealthy families are always aware of the double-edged nature of inherited wealth. Young people need guidance to deal with these mixed feelings, and this guidance is best delivered in personal discussions.

Generative families learn to meet regularly to talk about money and wealth; this stands in strong contrast to most families, even affluent ones, that do not talk about this. Parents recall conversations about the future. They try to take a light touch, making it possible for the next generation to become involved, but also establishing clear values and expectations for members of the next generation.

Explaining the meaning and use of family wealth is difficult. It demands a high level of engagement and give and take. Here is a creative example from a European family patriarch. He holds regular meetings with his two sons, who work with him in the business:

It's still small enough to do that on an informal basis, but we realize that in the future that's going to have to be more formal. Me and my sons (the third to fourth generation) have over the last ten years formalized meetings about transition. Twice a year, we sit together for twenty-four hours. We call this the “how are you meeting.” We exchange views of what kind of things we are going to work on for the next generation in a formal way. It's like a business family meeting. We do it here in my house.

The basic question is: How are things going in general, what are the top preoccupations in your head? What can make the other parties happier? We look at what do you like and what you don't like, what went wrong, or what can I do to make you happier? I make mistakes, and you make mistakes, and you are going to do that every week, and you have to accept the way you are. You cannot change that, but it's good that you know that so you will try to avoid these negative things.

What causes parents and children to start talking? It could be a crisis, a sudden or untimely death, or a financial windfall or loss. Or it can be a question voiced by a young family member. The parent can either open up or shut down the conversation.

It is difficult for parents and their offspring to talk freely and candidly. One reason is that young people feel that their parents are looking for specific responses and have a hidden purpose in what they are asking. So in order to have family conversation and to convey that they are open to hearing what their children think, parents have to ask more questions than state their opinions. Parents have to make it clear they want to hear the answer and not interrupt. If they get a one-word answer, they gently probe by asking further questions. This is called “having an attitude of inquiry rather than advocacy.” While parents do in fact have an agenda and opinions, waiting to learn from the young people what they think and feel first is a path to a successful family conversation.

Instilling values is rarely a formal process. Rather, through their own actions, parents set an example. However, several legacy families also initiate conversations with their children specifically about the meaning of family wealth. There seems to be no set age for doing this. Most families adopt a graduated method of conversation—sharing information and teaching skills at different ages as appropriate. “We've talked about where happiness comes from, having a good solid family, good solid friends, good food, a happy life at school. Things that are very tangible that you can call on all the time,” says an inheritor who is now chair of her family's council.

Most families who have been successful over multiple generations develop an ethic of thoughtful spending, setting limits on how much the family spends in an external environment that enshrines consumption. It takes the concerted effort of a parent to instill this sensitivity. This sixth-generation family, with a long history in several countries, embodies the following values:

Our values are focused on trying to live in a frugal way, trying not to abuse family wealth, and respect other people. We're distributing relatively modest amounts at a relatively young age. I've heard of other families where at age eighteen, they come into a trust fund where they're rolling in millions of dollars. It's important for us not to do that because that way, you're causing major issues for future generations.

The efforts described here are largely aimed at creating a family climate for these values to emerge. The founding generation's values are influential, as a third-generation family leader of a European family states:

The dividends are not something we've actually earned. Prior generations put together this company and did a lot of hard work, so we need to be responsible and wise with the money that we are given, not live extravagantly. We give a lot philanthropically and live modestly, like my grandfather and grandmother, who created the company. They chose to live in the same one-story brick house they've lived in for fifty years rather than deciding to upgrade to some kind of extravagant mansion. They were happy and content and satisfied with what they had and spent their money in other ways, whether it would be taking family and friends on trips to places or cultural things. There is an overriding mentality to not take for granted what you have and use it for education and long-term value.

Grandparents (elders) can be powerful teachers and models. Their venerated history and their special relationship with their grandchildren allow them to share their special family legacy:

We get together each summer for two weeks without the parents; it's our opportunity as grandparents to give back to the next generation some of our values, pass along some of our traditions, and nurture that history and those traditions. Every five years, our family has an important ceremony. We dress up. It starts at age five when the child is five years old; we plant a tree for them at our country house. At age ten, they get the treasure chest, filled with all of the history of the family and the DVDs and all the artifacts.

Developing Identity as a Child of Wealth

Even with parental support and engagement, a young person growing up in a wealthy household must develop a positive identity independent of the family.5 While there are many examples of materialistic, entitled, “spoiled,” even self-destructive and lost young people, the accounts by families in this study indicate that an engaged, values-based investment in the next generation by the family elders is a strong antidote to this tendency. Such an investment begins in the household and then expands to the extended family “community” of cousins growing up in the shadow of the family enterprise. The extended family reinforces the message by offering membership in a wonderful community that shares a business and commitment to positive social values. Membership has rewards but contains responsibility. To prepare to join the extended family enterprise as a steward, the young person first embarks on a journey to develop a personal sense of purpose and capability that in turn enables a positive role in the family enterprise.

The trappings of wealth are omnipresent for young people. This reinforces a sense that they are “special” in undefined ways, affecting expectations, questions, choices, and concerns about their future. This upbringing potentially provides inheritors an unusual amount of freedom to define themselves. But this same freedom and privilege also complicates making good choices and feeling good about their fortune in a world where people with inherited wealth may feel devalued by others with less who resent them. The way a young inheritor integrates the presence of money and wealth into his or her work, personal relationships, and life choices creates “wealth identity.”6

Knowing their life is subsidized, how do these young people motivate themselves among so many possibilities and choose what to do with their lives? Living in the outsize shadows of their parents, they wonder what they can do that will be significant and important. The opportunities of wealth can be lost if spent on meaningless, self-defeating, or destructive pursuits. Wealth can be a source of confusion if inheritors are not sure what it means to them, what they want to do with it, or how it fits into their lives. They find themselves doing a little of this, a little of that, and not having enough motivation to stick with anything.

Money alone is not the issue. It is also the status and recognition that comes with wealth, potentially leading to feelings of power and entitlement but also feelings of entrapment and isolation. Having and inheriting money has a marked impact on young people's core identity—on the beliefs and values that map how they view themselves as well as how others see them. Inheritors can experience guilt or feel that they do not deserve these gifts, complicating their ability to move forward with a positive relationship to their wealth. After learning from their parents, they have to work on their own to develop their own personal identity. Identity development does not emerge fully from parents' teaching. However, the experience of being part of an extended family community can aid their journey immeasurably.

Wealthy heirs nowadays grow up in a bubble, a “gilded ghetto”7 where they mostly meet others like themselves. Being protected, they do not experience diversity or have much opportunity to manage their own affairs. They do not go out or even play on their own. “Helicopter” parents watch and program their every activity, leaving little space for self-discovery.

With all of their wealth, their life experience is thus limited. Entering college may be one of the first times they are on their own, sharing space and getting to places on time without reminders. They may meet and learn from people different than them and may expand their horizons or remain secluded within a tight circle of other heirs. They need to be prepared and encouraged to take the first path—that of expanding their horizons.

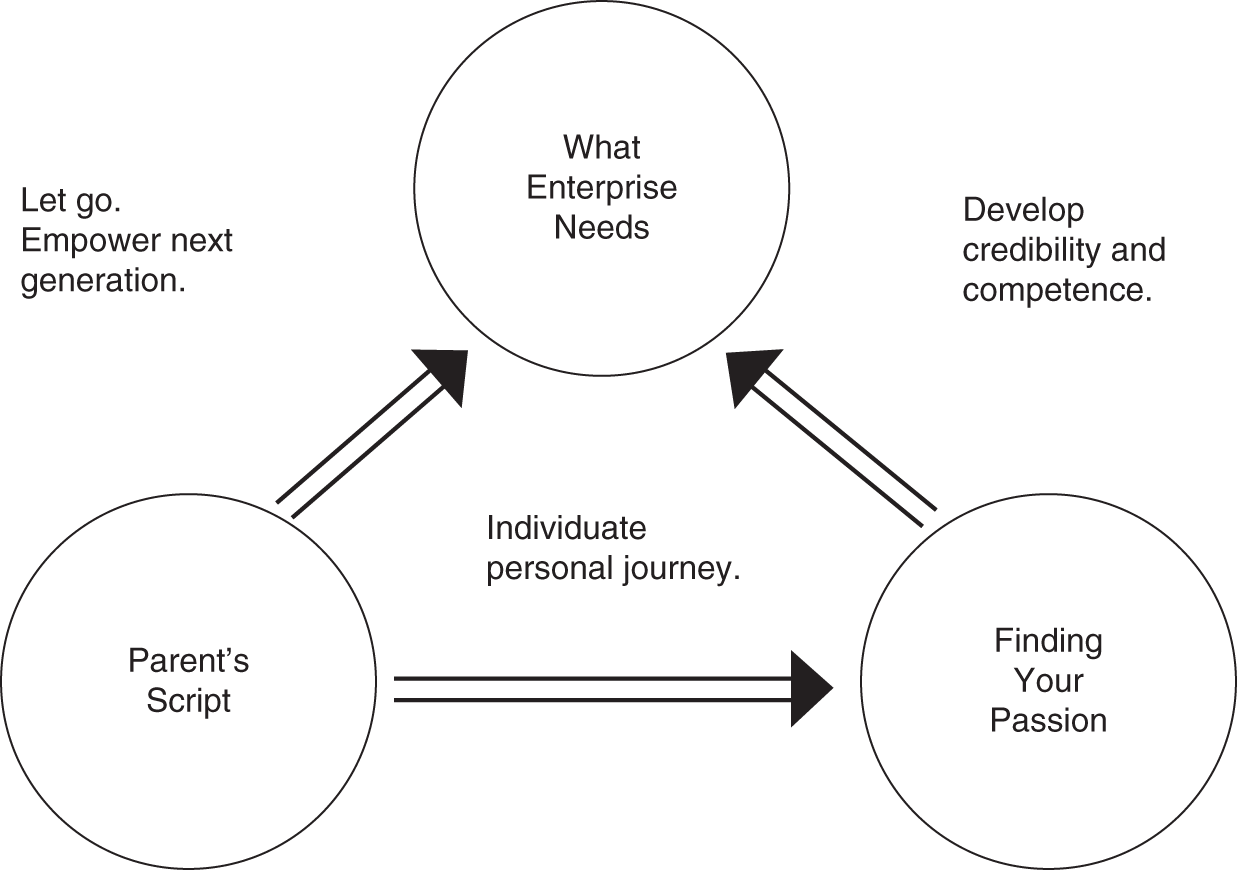

This developmental journey can be described as a triangle, with contributions from both the parents and the young person. (See Figure 13.1.)

A young person begins by learning from parental example and teaching. There can also be contribution via extended family activities. But the young person must then go on a personal journey—college, travel, relationships, work—to develop a sense of personal identity, capabilities, self-confidence, and a personal mission. As this journey unfolds, the young person then returns to the family, entering the family assembly and other family activities, in a variety of ways. This inside/outside/return model needs support from the elder generation.

Several family practices help young people in generative families navigate this path. First, the elders let go and allow young adults to find their way. Young people are encouraged to set out on their own, with appropriate support for things like education or travel, but not so much that they don't have to do some things for themselves. Particularly important is getting their first job outside the family, which is not given to them, and at which they have to perform on their own. Parental expectations should be made explicit, and parents should try as much as they can not to give mixed messages that show disapproval of the young people's choices. This can be tough for parents who feel strongly about certain directions.

Figure 13.1 Developmental journey of heirs.

Young people want their families to be interested and supportive of what they do; they want their parents to limit criticism and control over their choices. As their kids move toward maturity, parents can be appreciative but should exercise less direct control. They should resist their desire to use money to control choices and behavior. Young people develop best when they feel that while there are resources behind them, they are also expected to be on their own, even self-supporting. The family should have a clear agreement about what can be expected from the family and what the young people are expected to do in return. The presence of trusts and money is a problem if the rules for what is theirs and what is not are unclear.

Many young people report difficult experiences that propel them to learn and grow. If they don't struggle, they cannot learn. So parents who are rescuers, or who support their children in avoiding the consequences of difficulties, prevent learning. When a crisis or difficulty leads the young person to struggle, a common developmental sequence of identity development emerges that follows the lines of the “hero's journey”8—a person sets out to find something, encounters setbacks and difficulties, and overcomes them with some help from outside, all to end up with the prize that includes a sense of achievement, personal identity, and life purpose. Identity development can be viewed as a personal journey of difficult lessons and obstacles overcome, leading to public achievement and recognition as the young person returns home.

Young people who grow up with wealth inhabit a cocoon of safety, protection, plenty, and attention that has been called a state of “innocence”9—where they feel special and omnipotent, as if nothing can happen to them. Then, maybe on their initial journey outside the family something happens—a personal failure, a difficult relationship, or a challenge—that signals they can't rely on their parents or their money but have to fix it on their own. They are hurt and troubled, and this sets them to learn, reflect on, and come to terms with what they want to do with their lives. They may have to overcome bad judgment or habits. Doing so, they develop on their own some confidence, self-acceptance, and sense of purpose.

For parents, anxiety and desire for the best for their children can lead to rescuing them from any nascent difficulty, setting up a cycle of codependency where the child knows parents will always be there to take care of them. Parents who find their young adult children in trouble or hurting have to be able to apply positive tough love—emotional support along with the message that they have to solve their problems without unlimited parental resources. This lesson must first be learned by the parent.

Parental engagement is tricky at this stage. A parent should find a way to be in regular contact, as a sounding board for some (not all) experiences but taking care to be supportive and ask questions rather than preach or tell the young person what to do. Support does not have to mean solving a problem or intervening. Using one's means to smooth a path to college or a job is almost always counterproductive. For a parent used to having direct impact and taking action, this stage of support can be difficult to learn. Such a parent is not used to such an indirect role.

Young people who emerge from their own journey develop a sense of self strong enough to be ready to become involved in family ventures. They return home with their own success at doing something well and a set of skills they are ready to offer to the family.

Learning About Business and Work

Families usually expect and require family members to work. But the definition of work was flexible. As one family leader says, “We have a requirement for work, but we don't have a requirement for a salary, so if someone chooses their life work to be a volunteer coordinator for some charity, we consider that work.”

Another family developed what they call “the passion project,” in which each young family member was invited to develop a business or project, funded by the family, doing something he or she was passionate about. The goal was for the young person to demonstrate persistence, capability and commitment and to have his or her work recognized in some way by the relevant community. These projects were not necessarily remunerative; the family supported arts or social service projects if the receiver demonstrated its worth to the community.

Education about the family business happens informally and is important in developing expectations and focusing on career goals. This member of a Middle Eastern family with widely dispersed relatives recalls:

I was dragged to meetings since I was five or six. If there was a meeting on the weekend or I was on holiday, I would just get dragged along. So that was one way. Second, there were always business guests at home. There were always family members staying at home, nephews or uncles or people visiting for business. We lived with my grandfather, so there was always conversation between my father and my grandfather or my father and his brothers that were visiting. You couldn't help but hear although you didn't always understand it until later on. You heard and were involved passively.

Wealth opens up special opportunities for the rising generation to pursue rewarding career directions not open to less fortunate families. Noticing the musical talent shown by a young family member, a family elder—without the young woman's knowledge—asked the trust to invest in a rare instrument that was being auctioned. It was a good investment in a valuable antique and also a way to support a special talent. The young family member has gone on to teach and play all over the world. Other families report that they invest in the human capital of family members when they show special motivation or ability.

Skills for the Rising Generation

Substantial family wealth, generative families report, is a great challenge as well as opportunity for members of the next generation. While they pursue their own path in life, the many possible forms of shared family “capital” present family members with some inviting opportunities. In addition to the legacy businesses and investments, there is the possibility of founding new ones. Inheritors can look beyond personal benefit in their gift from prior generations. There are also service opportunities arising from family philanthropy. But to be useful, each successor has to develop professional skills and a personal commitment to become a steward (even when also pursuing their own life path).

What skills and capabilities are needed in the rising generation of a legacy family? Since the family enterprise looms large in the family psyche, young people's active focus on preparing for leadership takes three major forms:

- Business: In the second and third generation, family successors emerge who can work in the business (whether as executives or on the board of directors). By the third generation, the family has often either sold the legacy business or transitioned to a role where it oversees the business as owners with nonfamily leaders to guide the company. With a family office or extensive investments, the role of board member, trustee, or steward of assets demands different kinds of family leadership.

- Family: By the third generation, with many households comprising the extended family, successive generations must take active roles sustaining family connection and promoting cooperative relations and shared family activities to align, inspire, and educate the extended family. The family must develop collaborative, relationship skills to do this.

- Community: Family resources lead to many opportunities to serve the wider community, by partly supporting service careers and by initiating philanthropic and social entrepreneurship ventures.

Each of these endeavors is complex and demanding, and the generative family has a limited talent pool. The family must take steps to reap the most from each person by educating, guiding, inspiring, and inviting the most talented of the next generation into leadership.

Members of G3 or G4 growing up in separate households widely dispersed geographically may not know each other personally or feel connected to the family legacy or business unless they are actively engaged. In order to function as a unit, the generative family must renew its shared identity as a family enterprise in each new generation, aligning their many households.

As we have seen, generative families do not include all blood family descendants. Households and family branches may drop out of the shared entity while at the same time young people and new spouses enter. Each individual member, and the family as a whole, must develop a positive identity and reason for working as partners in the future. Family efforts are directed at using family resources to motivate and focus growing numbers of family members. “Generativity” means that the next generation does not rest on past success but commits to do more. For example, the next generation may take the business in new directions, perhaps starting new ventures that express the family's values in areas like social investment and entrepreneurship.

At some time, every member of the new generation must make a choice—to commit to the future of the whole family or to exit and go his or her own way. Generative families provide the opportunity to say “no” to the extended family. In every generation, some may take this opportunity to go their own way. By the third generation, the family may contain many smaller shareholders; some will be happy to sell their shares and use their capital in their own way. To ensure a robust future, the family must recruit them to join, and the family must do this by giving these young people a good reason to commit to be together as a partnership.

Great families see their rising generation as future leaders as they train and furnish them with personal and professional skills. It is no easy task to develop these leadership capabilities in several next-generation family leaders. A person with all these qualities might sound like a superhero! This looks like the wish list for a corporate leadership development program—and that's precisely what it is. All the efforts discovered in this study, from individual family learning to shared educational and development programs, are aimed at this level of development of leaders whose role is that of family “steward.” These outsize expectations for the next generation can be inspiring but also overwhelming. The key is to create programs that offer the right amount of challenge.

Developing a Positive Work Ethic

One aspect of raising new generations that almost every generative family agrees on is that they want them to develop a positive work ethic. Even if they work in social service roles, they want them to be passionate about something that makes a difference and become good at it. They find ways to encourage this.

Here is an account by a third-generation father about developing work values:

My older sister was born in a small apartment. I was born in a nice house. Then my younger sister spent her formative years in a much nicer house. All of us saw an incredible work ethic from my dad and uncle. A big challenge for me is how does my kid know how hard I'm working?

I knew clearly that my dad busted his ass. He was gone from six in the morning until ten at night six days a week. Sunday he'd sleep in until seven or eight. He made it to my games. One of the benefits of working in the family office is that I can take my kid to school every day. I don't miss a game. How does my kid see that work ethic? That's one of the struggles my dad never had. He just did it. My generation hopefully will struggle with that and hopefully have good answers, so the next generation is more comfortable with their wealth. Not that we're uncomfortable, but I think we're just learning how to do it. My dad couldn't teach me how to be born into wealth.

Family members have to rely on each other, to teach them the values that need to go with it. The reason my generation struggles with it is because we saw it, we lived it, [and] now it's ours. I've got to figure out how to make sure that my kids have a strong work ethic or understand the value of money. I went from a six-figure marketing job to teaching high school for 28,000 bucks yet still living the lifestyle of a six-figure marketing guy in Manhattan. That's not a reality for most people. How do you bridge that gap and let a kid understand? It's important that we educate our kids and rely on each other. That's where the family comes in. I see my responsibility for my niece who might not be getting that idea. I have to step in somehow because I think their mother is doing a poor job of it.

Several parents noted that they were especially active when their children transitioned from university to their first work experience. With the cushion of family wealth, young people looking forward to inheriting or working in the family business may have lower motivation to struggle and learn from adversity in their early work efforts. Indeed, adversity may be a new experience:

Their parents help them through those critical stages—the end of school and through university in their first years post-university. I think their critical stage is that first post-university job. They'd better start somewhere although it's not easy or pleasant. Both our daughters had first jobs at interesting companies but with terrible bosses. They learned really good lessons about life in the real world. They didn't stay very long with those jobs, but when you're starting out, you've got to get your hands dirty and start at the bottom. But some family members think, “I don't need to do it. I can sort of skip” that first phase out of university. But I just don't think you can. I didn't. I started working in a public works project as a young graduate engineer. The transition from university where it's still partying and fun to the real world where you often start with a pretty crummy job. They're going to start with a pretty basic job that's not going to pay them very well.

One second-generation elder sums up his generation's work with the following vision for the next generation:

I wish the next generation can see what we are and where we've come from merely as a background to who they will become. There is no sense of entitlement to either position or income. I hope they see it as part of their roots, something they're pleased about. And we'll give a little bit of time and intellectual bandwidth so they can be effective shareholders and owners. I don't want to look beyond that generation. Who knows what might happen; I'm not particularly dynastic. It was up to my generation to do the rational things when we crystallized the wealth. And in due course, it will be the opportunity for the next generation.

I want them to be able to function as a unit that enables them to avoid defaulting to “let's stop doing this because we don't know each other and can't work together, but let's make an informed decision about where we're going now as a family group.” I do think that there's value in that just because it's nice to know where you come from as an individual and as a family. There's a sense of identity and connection that gives people a good foundation to live their lives with knowledge about where it's come from. I always say we're not special. We just got lucky. If you're lucky, then what measures your success is how you capitalize on luck. In other words, be the best you can, then don't sit around. The disease of the inheritor, we all know, is the propensity to undershoot their potential because the inherited capital allows them to do that. Most humans are pretty lazy. I hope that would only be the minority of cases in this family, that they'll just get on and enjoy life and live life to the full. We don't need to go ten generations. We just need to do a good job each generation and see what happens.

Educational Programs

How do members of the rising generation actually learn and develop skills they will need to serve the family? Because of the size of the family and its special needs as a business family, the larger and longer-lived families in this study frequently develop custom-built educational skill development programs. These programs go beyond information sharing to developing the capability to take on leadership in the many facets of the family enterprise. They teach the specific skills to become a productive steward of the family enterprise: leadership, relationship, financial, and business skills. These are not skills they are likely to gain in higher education, or if they do, the special nature of the family enterprise makes it useful to supplement their education.

Family education programs focus on interpersonal skills like communication and can be similar to experiential corporate training but with the trainees being family members. Like executives, young people learn to work more effectively as a team, overcome (sibling) rivalry, and avoid bringing in conflict from the family:

Over the decade, we have done age-appropriate work across myriad subjects, including self-development, leadership, understanding self, and basic entrepreneurial practices. We reviewed every acquisition we've conducted over that decade. We review our financials twice a year formally with them. They've gone through our tax return in detail, and they have been to events that launch a new product, new rotation, grand opening, expansion of a site. When they were fourteen years old, we started talking about if they wanted to have a car, they had to make $5,000 on their own by say lifeguarding or cutting grass.

We also designed a summer experience for teenagers where you spend time in all the finance, IT, HR strategic planning, human resources, and small business initiatives. Some of them returned to their company and worked in areas that were particularly exciting to them. They entered college with an unusually deep appreciation for the complexities and opportunities it would take to be in the business world. I would call those very rich windows. You had a young person in an adult environment, listening and seeing the inner workings of a four-business-unit enterprise.

The family above appointed a family member full time as family relationship manager to oversee the development of the human capital of now hundreds of family members:

Parents need to make sure they're talking about the vision and values around the dinner table. That's key. Once they get older and they become inquisitive, we have a whole set of things we do with the family. We start at age twelve and categorize them from age twelve to twenty. We want some of the twenty-year-olds to be the mentors to some of the twelve-year-olds. We do functions with that age group two to three times a year. We call it “cousin-palooza.” Education doesn't revolve around what we do; it revolves around who we are. You get these kids together and introduce them to each other and like, “Hey, I know you; you sit next to me in science class. I didn't know we were related.”

Education programs are frequently geared for age cohorts. Younger children and teenagers attend gamified activities, like going on a scavenger hunt or creating a family tree. One family used the word “generage” to refer to family members who were of similar ages regardless of their generation. They designed programs for each generage.

Another family created a financial skills seminar, initially offered to family members over twenty-one. The first topic was about how to pay taxes. The second year the topic was budgeting. Younger family members expressed interest, so they lowered the eligible age to eighteen. Even more family members attended. Finally, for the third year on the topic of investing, they lowered the age to fifteen and had their largest attendance. This family has a tradition of family engagement, but they have been struck by the interest of their younger members. They have begun to add to their pool of “future family leaders.”

To ensure its future, generative families need to develop their successors in each new generation as capable stewards who are committed to the family's purpose and values, and are ready, willing, and able to take this on. Since the family enterprise is complex and demanding, every rising generation member must develop a positive personal identity and life purpose, and also find ways to serve the whole family enterprise. While in every family, some will not reach this goal, the family wants to create a climate where many if not most do. Parents in each household share this commitment and the collective family creates supplemental programs and activities to further these aims.

Parents in generative families must learn how to practice high involvement in these activities while exerting progressively less control. The next chapter will look further into how the generative family invites their rising generations to learn about the family enterprise and participate in what it does.

Taking Action in Your Own Family Enterprise

Developing a Personal Development Plan

As young family members complete college and graduate school and prepare for their careers, it is helpful to develop a plan for personal and career development. Many books and resources can help with this. One way to focus your growth is to create and manage a Personal Development Plan. To take personal responsibility for your future, it should have the following elements:

- Assess Your Skills and Capabilities

- What do you want/need to learn?

- How will you learn it?

- What preparation and experiences do you need to develop your capability?

- How will you assess yourself in these areas?

- Move Out of the “Bubble” of Family Privilege

- Leave home and discover the wider world through work, travel, and education

- Support yourself

- Take risks and try to learn about overcoming adversity

- Find a Mentor, Guide, or Coach

- Elder who has been there and can support and guide you

- Who are the best mentors? Where do you find them?

- Develop Credibility

- What is most important in your message to the family?

- What is the difference between interest, capability, and credibility?

- How do others know what you can do, how you can add value?

- How do you develop your credibility in the family and the family business?

- What is your plan for learning and developing your role?

- What do I have to learn in order to be ready for this role?

Wealth Messages

We earlier offered tools for having a family conversation about money and wealth. This conversation can take place one-to-one between each set of parents and each child, not as a single event but as an ongoing process. When a young person is choosing college or looking at a first job, family conversations can be helpful. When they are away at college, regular family phone calls or visits can offer a young person support while still allowing privacy for them to manage their own lives. Family agreements about support and help can be part of these talks.

What Is the Family “Deal”?

A key question for every young family member, and one that often is left unstated, is “What can I expect from the family in terms of resources, support, and aid just because I was born into this family?” This support may also be conditional on taking up certain responsibilities, having certain values, or behaving in a certain way. As a whole family, or in individual conversations, each young family member should be able to learn what he or she can expect and what the conditions are.

In this conversation there must be some exchange. Often young people grow up with certain expectations about fairness and what they were told. The family has to make the reality clear but also be willing to listen to the situation from the young person's perspective.

Often this can be done with a cross-generational family meeting, rather than individual ones, so that it can be clear how the expectations are similar or different for each person.

Assessing Basic Money and Wealth Management Skills10

Family education programs often teach young people core money management skills. These skills are important to all young people, but because these young people are expected to become stewards of family wealth, the family teaches these skills to the family together. These skills include how to:

- Feel comfortable with wealth.

- Talk about wealth in personal relationships.

- Manage personal wealth.

- Work with advisors.

- Save.

- Keep track of money.

- Get paid what you are worth.

- Spend wisely.

- Live on a budget.

- Invest.

- Handle credit.

- Use money to change the world.

Each young family member can respond to this list by checking the skills they have learned and those they want further help to learn. This can be done together as a family and the results used to develop family education programs and offer coaching to individuals.

Notes

- 1. John Adams to Abigail Adams, May 12, 1780, in Adams Family Correspondence, eds. L. H. Butterfield and Marc Friedlaender, vol. 3 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1973), 342.

- 2. Dennis T. Jaffe and James A. Grubman, “Acquirers' and Inheritors' Dilemma: Finding Life Purpose and Building Personal Identity in the Presence of Wealth,”Journal of Wealth Management 10, no. 2 (2007), 20–44. This model was amplified and described in greater detail in Grubman's book Strangers in Paradise: How Families Adapt to Wealth Across Generations (Northfield, MA: FamilyWealth Consulting, 2013).

- 3. George E. Marcus with Peter Dobkin Hall, Lives in Trust: The Fortunes of Dynastic Families in Late Twentieth-Century America (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1992), 55.

- 4. Hartley Goldstone, James E. Hughes, Jr., and Keith Whitaker's book, Family Trusts: A Guide for Beneficiaries, Trustees, Trust Protectors, and Trust Creators (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), explains the opportunity to expand this relationship.

- 5. The observation that it is difficult to grow up in a wealthy household and to develop a positive identity is an insight that comes from a group of researchers including John L. Levy, Joanie Bronfman, Joline Godfrey, Lee Hausner, James A. Grubman, David Bork, and Madeline Levine, who have each written extensively on this topic.

- 6. Stephen Goldbart, Dennis T. Jaffe, and Joan DiFuria, “Money, Meaning, and Identity: Coming to Terms with Being Wealthy,” in Psychology and Consumer Culture: The Struggle for a Good Life in a Materialistic World, eds. Ted Kasser and Allen D. Kanner (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2004), 189–210.

- 7. Jessie H. O'Neill, The Golden Ghetto: The Psychology of Affluence (Milwaukee, WI: Affluenza Project, 1997).

- 8. This concept, developed by mythologist Joseph Campbell, suggests that over the course of a life, a young person often follows a common developmental journey told in different ways across cultures. The hero's journey is a quest. The young person sets out into the world, faces a deep challenge and danger, finds allies, overcomes the challenge, and returns home as a hero. See Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (Princeton, NJ: Bollingen Foundation, 1949).

- 9. This term was coined by George Kinder in The Seven Stages of Money Maturity: Understanding the Spirit and Value of Money in Your Life (New York: Dell, 1999) to denote those who enjoy wealth but have no idea where it comes from or how to manage it.

- 10. Adapted from Joline Godfrey's book Raising Financially Fit Kids, rev. ed. (New York: Random House) and from conversations with James A. Grubman.