13

EVERYTHING THAT CAN BE DIGITAL, WILL BE: CREATIVE TECHS, DEVELOPERS, AND THE MOBILE FUTURE.

THE DIGITAL REVOLUTION IS OVER. (Spoiler alert: digital won.)

Today, as a writer or art director, you'll be expected to come up with everything from ads to mobile apps, tweets to augmented reality.

Note I said, “come up with,” not code. You don't have to learn coding or take every technical course on LinkedIn Learning. Being a bad-ass art director or copywriter still qualifies you for most agency creative departments, particularly the larger ones that also employ digital developers, as well as people in UX (user experience) and UI (user interface) designers. Art directors and copywriters routinely team up with all these specialists to tackle big projects.

As a traditional art director or writer, you may not be able to sketch wireframes or build prototypes like the technical people on your team, but you'll still need a good sense of how they do it and how to work with them. If you don't know when to involve them, when to lead, and when to shut up and take their cues, you'll be less effective as both a team member and as a creative. You'll have better digital ideas if you have a good sense of how they're brought to life, if you're what's called a “T-shaped” art director or copywriter.

Generally, the term T-shaped refers to employees who have very deep skills in one area (the downstroke of the T) and also possess some proficiency in other skills (the horizontal stroke). Understanding how digital creatives think will help you become a better traditional creative and increase your value to any creative organization. That's because the chief output of more and more ad agencies isn't advertising per se, but digital experiences and mobile technologies. So, yes, it is a good idea to keep learning about any emerging technology that appeals to you, whether it's drones or wearable tech.

Wieden+Kennedy creative director Tony Davidson agrees. “I'm not even sure the future is a writer-and-art-director team anymore.” In William Spencer's Breaking In, Davidson said, “I get a sense that the kids coming through these days want to do a lot more. They want to be an animator, they want to be a director, they want to be a writer. I love the idea of a hybrid-creative person who can move between disciplines.”1

Google's Valdean Klump agrees and describes the value of a wider skill set.

What impresses me most is the ability to make things. More and more these days, young people are coming into the business able to shoot their own commercials, create websites, program games, take photos, make animations, build Facebook apps, and generally act as one-person ad agencies. This makes CDs salivate because getting ideas off the page is at least as hard as getting them on paper in the first place… . If you can make things and make them well, you will never be unemployed.2

Having been a CD, I remember wanting to recruit the most techno-geeked-out, code-slinging, wired-in web brats I could find. However, I wanted writers or art directors who knew how to take a blank sheet of paper and make something interesting and beautiful happen. But the ones who could think both conceptually and digitally? Those are the creatives I really wanted. They're the creatives of the future.

CREATIVE TECHS AND DIGITAL DEVELOPERS.

Way back in a 2014, Google posted a job opening for a creative technologist. They first described this position as one of “collaborating on the ideation and development of ‘never been done before' digital experiences in partnership with top brands and agencies” and “contributing to the development of cutting-edge prototypes in the field of creative technology.”3

The description still works today and appears to be interchangeable with the term experience designer. So interchangeable, in fact, that one of the nation's top schools describes their experience design program like this: “Experience Design students work on creative teams to concept, design, prototype, and build brand experiences that help people, and push the envelope of what is technologically possible.”

Tomato, tomahto. I'm going with creative techs.*

A creative tech is skilled in using all the newest media technologies in the service of branding, advertising, and marketing. This person introduces emerging technologies into the concepting process and is involved from the campaign briefing through final delivery. They use amazing programs and software—which are way beyond Adobe—like Unreal Engine, Three.js, Unity, and TouchDesigner. (There'll probably be 50 more cool programs to play with by the time this book reaches your hands.)

Creative techs help design mobile experiences but also work in spatial design, brand installations, AR/VR, wearable tech, and 3D modeling. They also know all the social platform's APIs (application protocol interfaces), which allow people to use Twitter, Facebook, and the ’Gram. (Yeah, I'm hip.)

Whether it's bringing a technical understanding of location-based platforms, designing communities, or executing Facebook applications, the creative tech helps turn campaign ideas into cool digital experiences. In addition to blue-skying concepts with the art director–copywriter team, the creative tech may build prototypes to test ideas or be a liaison to another kind of digital expert often found inside agencies—the digital developer.

A digital developer is a technical expert who designs, develops, and maintains websites and other online applications or services. If there was a continuum going from AD CONCEPTUAL to TECH DIGITAL, creative techs would be closer to the AD CONCEPTUAL side and digital developers closer to TECH DIGITAL.

Now, all those cool programs I just named, the ones creative techs use? It was developers who made those programs, out of code—with languages such as Python, Ruby/Ruby on Rails, C++, and Swift. Code is the language developers input to a computer so it understands your commands and does what you want it to. The PLAY button on the screen is simple—as all interfaces should be—but all the code inside, what makes a hunk of metal on your desk play a video, that isn't.

Some agencies outsource the dev, as it's called, and some don't. Also, there are creative techs who are capable of doing the digital development themselves. Overall, in an agency that's more digitally focused, you'll find both digital developers and creative techs in the middle of the creative department next to the writers and art directors. (In fact, someone accurately observed “most creative techs in the agency business seem to be disguised as art directors.”)

In Eliza Williams's This Is Advertising, Alex Bogusky promoted this cross-functional grouping:

[At Crispin] we've talked about a time when there will be no specialization on the creative floor, but the technology moves so fast it's difficult to keep up with it unless you specialize in it… . [So] you want the creative people sitting close to the programmers and the information architects. Because although they may not be charged with creative, they're going to have ideas and influences the creative aren't going to understand unless they're sitting adjacent to those folks… . It's a little weird to not know how to do that stuff, because the knowing really influences the execution of it.4

If you're an art director or copywriter and find yourself in such an environment, it'll pay to form partnerships with developers and creative techs. Invite them to concepting sessions and your team will get more interesting work. You'll be adding your strengths in narrative, writing, and design, and your partner's systems thinking will start to rub off on you.

It's important to note information about all these emerging technologies isn't going to walk up and introduce itself. (I can hear some boss saying, “People, these blogs aren't going to read themselves.”) You need to start devouring as much information about technology as you can. Now.

Like everything else in advertising, creative tech starts with the customer.

Marketing has become less about messaging and more about content and utility, and nowhere is this truer than in the world of creative technology.

Creative technologists help us make things on behalf of brands. They can create content, craft experiences, and make things people might find useful.

Useful can mean it helps a customer do something, or maybe it solves a problem for them. This sounds a little like we're describing a tool and although that's not a perfect analogy, it'll do for now. And if we're building tools for customers, the question becomes, what are the tools for? This question leads us to a design principle technologists employ called goal-directed design. The term was first proposed by software developer Alan Cooper and describes a customer- or user-centered method for creating things.

A customer goal can be anything, from successfully filling out a tax form to selling a car online. By studying a customer's goals carefully, we can craft brand tools that not only solve the problem but do it so elegantly or delightfully that using the tool is a brand experience in itself.

So, the first part of every creative tech's process is to become “user-centered” and take a deep dive into the customer experience. Author and digital CD Adam Harrell asks, “How do [the customers] perceive the product or service? What are the pain points they have that the product or service solves? What basic human desire are they trying to solve through their purchase?”5

In traditional advertising, brands use demographic information about their target customer—for example, age, race, gender, marital status, income, education, and employment. But creative technologists and engineers create user personas. The biggest difference between user personas and demographic profiles is that personas are built around the user's goals.

Adam Harrell explains why this matters in his wonderful book, Creative Direction in a Digital World: “A good persona should help your team make important decisions such as what content to create or features to prioritize… . It should introduce the audience's worldview and speak clearly to their life goals, experience goals, [and] end goals.”6

Creative techs list these goals when they're creating a persona. What a user is trying to accomplish is called the end goal. (“I want to sell my horrible car.”) How a user wants to feel during the actual experience is, obviously, the experience goal. (“Wow, this app made selling that heap easy.”)

Finally, personas can help creative techs avoid common design mistakes, such as “self-referential design”—where we project our own models of user behavior into a design that then mystifies the first person who tries using it.

Creative technologists design user experiences.

With the goals of these personas in mind, techs and designers brainstorm different interfaces to make using the website or app easy and, dare we say, fun. By designing simple user paths, smart designers can craft experiences that unfold effortlessly.

Apple was one of the first digital companies to leverage the marvels of user-centric design. The first iPhones, to everyone's amazement, didn't come with instruction books; we just intuitively knew how to use them. In fact, Jobs's first edict to the design team was “I want it to have one button.” (Which it did, sort of, if you didn't count the buttons on the sides.)

Although the iPhone appeared to be a simple device, the complexity was handled back when Apple designed the interface. “Steve spent twenty minutes with the engineers working on the best place within a [tiny] section to put three words. He was that focused on details.”7 That Apple simplified complexity with such aesthetic elegance helps them to this day to position their phones in the luxury price range. It's as if their designers' mantra was the Shaker proverb, “Don't make something unless it is both necessary and useful. But if it is both necessary and useful, don't hesitate to make it beautiful.”8

This attention to detail is what made the original Apple-philes love the brand. With every click, users experienced some new frictionless way to get what we wanted, cementing many of us to the brand for life. These details, called microinteractions, don't have to be critical operating features to bring surprise and delight to customers.

But these elegant interfaces don't just happen. Creative techs work through a process that begins with sketches on paper. Once the idea begins to take some shape, they'll make a wireframe, which is basically a blueprint. Images of wireframes can look like a pile of coat hangers to the untrained (me), but they help designers get a detailed understanding of how the working product or experience might feel.

As the work-in-progress gets refined, many teams create a high-fidelity mock-up to present to clients. Creative technologist Joe Toscano says, “High-fidelity mock-ups are the deliverables that get people excited. They're filled with color, beautiful photography and content.”9

Finally, a prototype is created. A prototype isn't the real thing yet, but to anybody using one, it looks and feels finished. Working prototypes enable designers to conduct user tests and to work out bugs in the user paths and other glitches.

Brand experiences can be immersive.

Digital experiences are often found in their own dedicated websites. But when the experience is housed within the brand's site, they more directly connect the customer's experience to the brand.

Adam Harrell used an interesting metaphor to describe why this is helpful, citing Walt Disney's belief that every theme park needs something like Disney's Magic Castle. “[The] website should have a piece of tent-pole content that acts like a castle in a theme park. It should be memorable and remarkable. It could be an incredible video, beautiful data visualization, a useful tool, or an engaging interactive experience.”10

The brilliant CHE Proximity agency in Melbourne provides us with another example, this one flexing some serious creative tech.

On behalf of CarSales.com (Australia's largest online classifieds for second-hand cars), the agency introduced “AutoAds.” This was a cloud-based program that automatically generated what appeared to be big-budget car commercials for any old POS beater you wanted to sell.

How it worked looked simple, but the complexity was in the coding. Customers didn't have to do anything other than list their car for sale with the usual details—the make, model, mileage, price, and a photo. The system then merged that data with over 5,000 different pre-produced video and audio clips. Then it sent the customer an email with several very clichéd car commercials, with themes like Tough, Family, or Luxury. Mixed into each slick high-end commercial, jarringly, was a photo of the customer's old POS car.

In the first week, Australians swamped the site creating nearly a half-million customized commercials. Unsurprisingly, they shared them with friends online. To supercharge the campaign, CarSales.com also selected some of these commercials and aired them on national TV. (This case history, like most others in this book, is viewable on YouTube.)

Remembering Bogusky's Idea-as-Press-Release process, it's clear this was an idea you could describe with a short press release headline. In fact, on one Australian morning news show, the chyron read, “OLD CARS GET SLICK ADS. Every used car in Australia gets its own commercial.”

Less expensive but equally delightful was the experience “Play the City,” created by TBWA/ChiatDay to herald the return of the Grammy Awards to New York City (Figure 13.2).

The experience took place, appropriately, in the back of an Uber. As passengers boarded, they may have been curious about the musical scale across the back window. But once notes began appearing on the scale with corresponding musical tones, riders could tell the visual notes and the music were being generated in real time, triggered by people and objects passing outside the window.

Figure 13.2 Check out “Play The City” on YouTube.

As with many cool branded experiences, the entire thing was captured on camera and the content shared in other media, one of which was national television—a commercial for the Grammy's, which aired on the big night. The whole project is another example of collaborations that blend the storytelling of ad creatives with the technology of systems thinkers.*

Build things out of connected devices.

Using technology to tell brand stories can make a customer experience immersive. Things can get even cooler when different digital platforms and devices are combined to create a single experience.

One of the most impressive examples of this we've discussed already—the famous British Airways “living billboard” (Figure 6.12). Many different technologies had to be linked together to make the little boy able to spot when a plane was flying overhead and to correctly identify its flight number and destination. Systems like the flight data from the airline client, geofencing to predict when the planes would be flying directly overhead, and weather data, which needed to be real time. (If there was cloud cover, the digital board switched to another advertiser.)

Part of what makes such connections possible is ubiquitous computing (or, if you wanna sound cool, ubicomp). Ubicomp is a concept in software engineering where computing is made to appear anytime and everywhere, across different devices and platforms. (For my sci-fi peeps, basically “Skynet.”) Experienced digital developers can rig all kinds of different technologies, a notable example of which happened in Volkswagen's sponsorship of a music festival in Sao Paulo. (Figure 13.3).

VW's task to BBDO was to supercharge the exposure of the VW Fox to young people. The venue they chose was Planeta Terra, one of the largest music festivals in Brazil. To activate their campaign, they hid 10 pairs of free tickets around Sao Paulo, the largest city in the Western hemisphere.

To reveal the locations of the tickets, all people had to do was tweet the hashtag #FoxatPlanetaTerra. The mechanics were simple (or rather, appeared to be simple). By creating a mash-up of Twitter and Google Maps, the more people tweeted #FoxatPlanetaTerra, the closer Google Earth zoomed in on the GPS locations of the tickets. The first to arrive at each location would claim their prize. Over the next four days, hundreds of thousands of music fans tweeted and retweeted the hashtag until it trended number 1 on Twitter. This, in a city of 22 million people.

Figure 13.3 Volkswagen and BBDO create a mash-up of Twitter and Google Maps.

Connected devices can also work on smaller scales, too, as in this student concept for Kindle's e-books.* The idea was simple. Wouldn't it be surprising if you were reading an e-book like, say, The Great Gatsby, and then later you got a tweet from Jay Gatsby? What's even cooler is this idea is easily scalable. Pick a book, pick a character—any publisher who wanted to join the program could give customers a more immersive reading experience just by connecting these systems.

Always be inventing.

Being able to tell a recruiter you're a “maker” improves your chances for landing a job. Just being an “idea person” doesn't carry the weight it once did.

Makers are a growing subculture of people who play and invent in the worlds of digital tech, engineering, robotics, and 3D printing.

The movement is popular enough to give birth to events like Maker Faires and companies like SparkFun. Held worldwide, Maker Faires are like bad-ass science fairs that showcase makers, tinkerers, and hobbyists who love to play with technology. SparkFun is an online retailer of microcontrollers, circuit boards, and all the other ingredients you need to build stuff for the Internet of Things.

Many art and technical schools are now offering creative technology programs. In some classes, students start with Arduino, an open-source electronics platform based on easy-to-use hardware and software. Arduino boards can read inputs (light on a sensor, a finger on a button, a Twitter message) and then turn them into an output, such as turning on an LED or publishing something online.

What follows are a few of the other technologies and systems creative technologists use to bring brand stories to life:

- Augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and mixed reality (MR)

- IoT (Internet of Things), which include everyday electronic objects, from cars to baby monitors

- Web and mobile apps

- UI/UX platforms

- Voice-enabled tech

- NFC (near-field communication)

- RFID (radio frequency identification)

- AI (artificial intelligence)

- Neural networks: AI technology that learns human behavior and mimics the human brain

- Robotics

My friend, professor Clark Delashmet, says, “Basically, if you can think of a digital product or application, you can probably make it.” To illustrate Clark's point, here's another student project created by applying some of the principles covered here.*

The business challenge was, “How do we re-introduce TAB cola to Gen Z?” TAB is a very niche Coca-Cola product first introduced in the ’60s, one that is still hanging on by a thread thanks to a community of diehard fans. The student team interviewed a brand manager at Coke and was told TAB cola would likely never receive any media investment and if anyone were to come up with a viable proposal, it would have to run entirely in social media.

So, they asked themselves “Okay, how can we connect TAB cola to this gif-loving, meme-generating generation?”

Answer: by asking people on the internet to be their medium and to hashtag “gif-us-fame,” the very words that greet visitors at the landing page of the site they coded from scratch (Figure 13.4): “We at TAB cola had no marketing budget, so we asked the Internet to #GifUsFame.”

They paired TAB with Giphy and gave the internet access to prekeyed shots of TAB cola cans. (Prekeying an image gives it something like a green screen effect, creating a clean, cut-out image of the can.) Using these cut-out images of TAB cans, viewers could create whatever memes they wanted just by inserting them into any of Giphy's huge collection of pop culture memes. In an elegant finishing touch, visitors could scroll through the site's sample gifs (included in Figure 13.4) for inspiration, simply by pushing the TAB key on their keyboards.

The examples discussed here are just a taste of how brands are using technology to tell their stories in new ways. They don't look and sound like advertising but that's what they are. They bring a brand to life, they let people participate if they care to, and lets them share the results—often by using their mobile phones. (Tortured segue.)

Figure 13.4 You can still see this student project at gifusfame.com.

IF DESKTOP INTERNET IS DIVING, MOBILE IS SNORKELING.

A tech website recently reported mobile is now the dominant platform for accessing the internet.11 It's like some little phone just told all the big-ass tabletop computers, “Dude, hold my beer.”

The phone is officially the first place anybody goes for anything. It's where everything is headed—the entire web, the combined knowledge of all history, the ability to purchase every product from every brand at every store, on-demand, anywhere, 24 hours a day, is now in everybody's pocket.

Knowing this, clients are shifting media dollars into mobile work. Josh Palau of Johnson & Johnson says, “We are pushing everyone to think mobile first.” My friend who's a CD at a big agency told me many of the briefs she's seeing call for mobile-only executions.

As we begin to discuss using mobile on behalf of brands, we're going to start at the same place we've started everywhere else in this book—with the customer. Nobody's concepting anything until we know exactly who we're talking with.

Additionally, we'll need to understand the context in which the customer is using their phone and why they're using it. People get out their phones for all kinds of purposes: to look up something, to get directions, to explore and play, to check in, to post things and, of course, to buy. (Keep in mind the “Pitch, Play, Plunge” approaches from the previous chapter.) For a mobile idea to be effective, it must be relevant to the context in which the customer is using their phone.

The things we come up with must also take into consideration how people use phones—which is usually in a hurry and on the move. One agency creative was heard to say, “I like to imagine one eyeball and one thumb.” Mobile use is often just a quick dip into the web to find something or do something, very different from how we often use our computers—for deeper dives into research, content aggregation, or writing books like this one.

So, taking brands into the mobile sphere requires a shift in our thinking. J&J's Josh Palau says, “It's about being present and useful with your audience. Align content with what customers want and respect them. Provide something that's quick, educational, helpful, and which fits into the platform they're already on.”

There are so many possibilities with mobile this small book can't hope to cover them all, so we'll limit our discussion to some creative advice, a few examples, and how mobile fits into a brand's overall media mix.

One of the simplest ways to think about how mobile fits in is as connective tissue. You can drop a smart code (QR) into a concert poster and a fan can get a free song or buy tickets from the website. Text a short code number from a print ad and a reader gets a free sample in the mail. Scan the bar code in the store and a shopper can see how much the product costs across the street. But these very actions (scanning, texting, buying) speak to the key difference about mobile, one that makes it more than just another medium—its utility.

Mobile is the place where brands can do things instead of just say them. And customers can do things, too, because mobile can incite action. “Instead of thinking of mobile as an advertising distribution platform,” writes Rick Mathieson in The On-Demand Brand, “it's far more powerful as a response or ‘activation mechanism' to commercial messages we experience in other media.”12

Leverage mobile functions to create cool ideas.

The most common advertising in mobile and online is the irritating and boring banner ad. To me, they're like pixel-zits and I never click on them. Apparently neither do most people—a full 60 percent of mobile banner clicks are accidental, according to FullMoonDigital.com.13 (My disdain of the lowly banner ad is elitist, I know, but I'm just not a fan.)

Let's talk instead about the kind of mobile marketing that makes use of technology inside the phone, as well as things like near-field communication (NFC) and radio frequency identification (RFID) (see Figure 13.5).

Near-field communication enables a phone to interact with other nearby devices by providing a wireless connection. Apple Pay and Android and Samsung Pay all operate using NFC. Mobile payments are the norm in China, but the US is catching up and it's being adopted by more businesses, mostly as digital rewards programs and virtual loyalty cards.

Then there's geofencing. Here a virtual boundary is created around a real-world geographic area; a 20-block radius around a brand's retail store, for example. When a mobile device enters or exits a geofence, the system uses RFID, GPS, or cellular data to trigger a targeted marketing action to that device. It can be a text, a free offer, a coupon, or a social post. (All the major social media platforms have geofencing capabilities.) Smart marketers will make receiving such messages an opt-in (the customer chooses to participate), and effective messages always have a clear call-to-action requiring immediate action. Sephora's geofencing, for example, sends nearby mall visitors digital coupons good for that day only.

Figure 13.5 As you concept, consider how the phone's various functions could be used to help your brand help customers.

NFC can also link smartphones to billboards. As part of its “Real Beauty” campaign, Dove posted a digital billboard asking passersby to use their phones to vote on their idea of beauty (choosing between two pictures) and posted every vote, in real time, up on board.

Augmented reality (AR) is another cool use of mobile. AR usually takes a phone camera's image of a real-world environment and augments it with computer-generated sensory input such as sound, video, graphics, or GPS data.

The Swiss airline Edelweiss used AR to promote its new direct flights to Buenos Aires by combining the airline's flight schedule data with the user's smartphone GPS and compass data. Push notifications invited people in real time to look up and catch Edelweiss planes bound for Buenos Aires. Every time a person “caught” one, they improved their chances of winning their own ticket to Buenos Aires (Figure 13.6).

Web-based and native apps.

The most effective mobile apps are baked into the firmament of a brand's true value proposition. There are two main kinds: one's called a web app, which lives on the servers and is accessible across different platforms, and native apps, which reside in the user's device and are displayed inside the app's natural environment.

TBWA/Hakuhodo created a popular web app for Tourism Australia to promote the country to social-media-savvy Japanese travelers. Realizing selfies are a part of many people's travel experiences, and that Australia's popular tourist sites are wide landscapes, they created “Giga Selfie” (Figure 13.7). At each site along the Gold Coast, travelers could connect their phones to a distant camera (via a dedicated Wi-Fi) and then take an ultra hi-rez selfie by remote control.

Figure 13.6 Augmented reality lets brands tell stories in “revealed space.”

Giga Selfie is a web app. As for native apps, well, we've already discussed one in Chapter 10: Burger King's “Burn That Ad.” The Edelweiss airline app that captured planes bound for Buenos Aries was a native app. Another good example is one Ogilvy created for KFC in Australia—“KFC's Secret Menu.”

They discovered the restaurant's staff loved hacking the menu, coming up with different arrangements of items. So, KFC gathered their favorite staff creations, gave them names like the “Beese Churger,” and hid them on a secret menu in their native app. (To even find the menu, you had to pull down on the screen and hold it for 11 seconds—you know, for their 11 secret herbs and spices.)

The cool part was they told no one about the secret menu and just let their internet fans find it on their own. And find it they did, in huge numbers. Secret menu customers spent over 75 percent more per order. On top of that, customers kept the app for months—impressive when you consider over 75 percent of apps are uninstalled within three days.14 With an always-on idea this good, brands can earn a regular spot in a customer's mobile device.

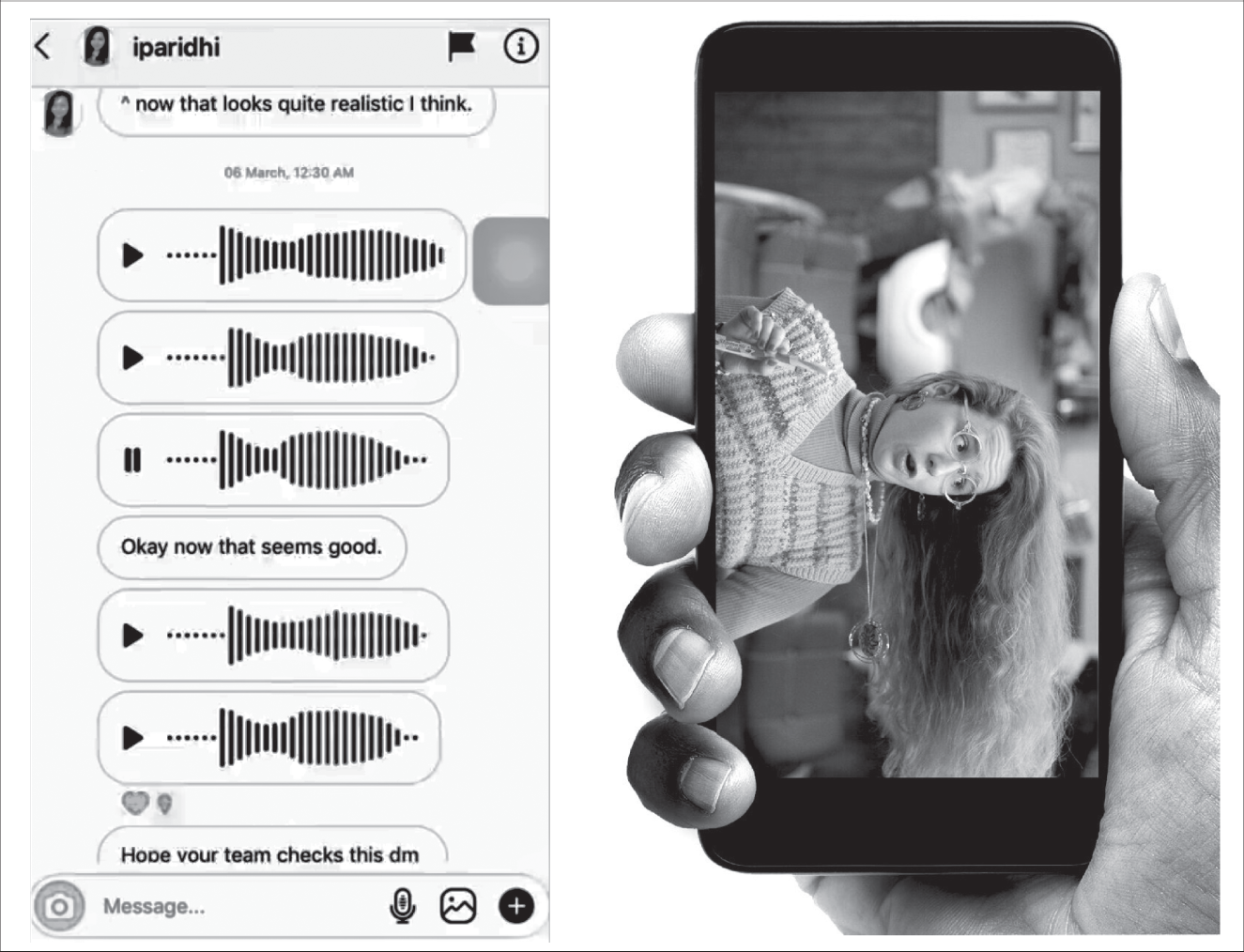

In India, the popular food-delivery program Swiggy promoted its services by leveraging Instagram's voice note feature. To win free food vouchers, they challenged IG users to create sound waveforms in the shape of different food items (the fish in Figure 13.8, left) and then send their creations to the brand's page.

Figure 13.7 That tiny dot in the square (center) is the person who took the photo.

Mobile ads.

Although mobile advertising is only a subset of mobile marketing, straight-up mobile ads can also be engaging.

On YouTube, DDB Chicago posted a delightful vertical-only ad designed to be viewed on mobile for Starburst Swirlers—their first venture into the “rope-stick” confection category. Titled “Best Enjoyed Vertically,” the commercial shows a woman trying to share her Swirler in a hair salon turned completely on its side (Figure 13.8, right).

Another example of mobile advertising was a campaign of radio commercials BBDO purchased on Spotify for Snickers. True to their long-running campaign, “You're Not You When You're Hungry,” the commercials were triggered when a listener stayed with a musical genre not in their usual playlist. Spotify's streaming intelligence would pick up on this change and these particular listeners were sent a Snicker's branded playlist, “The Hunger Hits.” Here, thematic songs like “Be Yourself” by Audioslave and Ceiling Fan's “Hang Onto Yourself” helped send the brand's message.

Figure 13.8 On the left: Swiggy's food-delivery service asked fans to make voice-created images of fish and other food shapes on Instagram. Right: Starburst candy's wonderful “Best Enjoyed Vertically” commercial.

Figure 13.8 On the left: Swiggy's food-delivery service asked fans to make voice-created images of fish and other food shapes on Instagram. Right: Starburst candy's wonderful “Best Enjoyed Vertically” commercial.

As you look back at these examples of mobile creativity, you'll notice they share certain characteristics: they're all contextual, interactive, and social. There's one other characteristic these mobile examples share, and they share it with every single cool idea in this book—a deep understanding of the customer. Mark Avnet of the VCU Brand Center says the customer is key. “Starting with technology might make you a great production company. But starting with people can help you become a great strategic and creative marketer.”15

We'll visit mobile again in Chapter 14 to discuss how it applies to social marketing.

NOTES

- 1. William Burks Spencer, Breaking In: Over 100 Advertising Insiders Reveal How to Build a Portfolio That Will Get You Hired (London: Tuk Tuk Press, 2011), 51.

- 2. William Burks Spencer, 246.

- 3. “Creative Technology.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_technology#cite_note-25.

- 4. Eliza Williams, This Is Advertising (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2010), 30–31.

- 5. Adam Harrell, Creative Direction in a Digital World: A Guide to Being a Modern Creative Director (New York: CRC Press, 2017), 4.

- 6. Adam Harrell, Creative Direction in a Digital World, 9.

- 7. Jay Elliot, The Steve Jobs Way: Leadership for a New Generation (New York: Vanguard Press).

- 8. Adam Harrell, Creative Direction in a Digital World, 36.

- 9. Joe Toscano, UXCollective.com, August 17, 2016.

- 10. Adam Harrell, Creative Direction in a Digital World, 60.

- 11. Christo Petrov, “In 2021, Mobile Phones Generate 54.25% of the Traffic, Desktops 42.9%.” Techjury, July 6, 2021, https://techjury.net/blog/mobile-vs-desktop-usage/#gref.

- 12. Rick Mathieson, The On-Demand Brand: 10 Rules for Digital Marketing Success in an Anytime, Everywhere World (New York: Amacom, 2010), 184.

- 13. “Top 5 Best Mobile Marketing Campaigns of 2019 and 2020.” FMDM, n.d., fullmoondigital.com/top-5-best-mobile-marketing-campaigns-2019–2020/.

- 14. Quettra, based on anonymized data points from over 125 million mobile phones.

- 15. Robin Landa, Nimble: Thinking Creatively in the Digital Age (New York: HOW Books, 2015), 80.

- * Job titles and their descriptions in the digital industries vary widely depending on who's talking. Because I'm talking, here are my definitions. XDs, or experience designers (or creative techs), are experts at applying design thinking to the form and function of customer interactions with a company, its stores, services, or products. UX, or user experience design, refers more narrowly to the interactions between a person and a product or device. And finally, there's UI, user interface design, a digital-only term referring to how a product is presented visually to the end user. UIs are responsible for the user-facing designs, and they make sure the interface visually communicates the path the UX designer laid out.

- * In an article about the making of “Play the City,” producers from Tool, LA, said they used “two computers (with a decent GPU), a GoPro camera and some extra hardware to glue everything together, a Black Magic Design Capture card, a YOLO detector (a real-time object detection system), and Ableton Live. All applications were built using open Frameworks, which is an open-source C++ toolkit for creative coding. Without these open-source projects, we wouldn't have been able to build this installation in such a short time.”

- * Ashley Fernandez.

- * Neha Guria and Hien Le.