1

A BRIEF HISTORYOF WHY EVERYBODYHATES ADVERTISING: AND WHY YOU SHOULD TRY TO GET A JOB THERE.

I GREW UP POINTING A FINGER GUN at Mr. Whipple. You probably don't know him, but he was this irritating guy who kept interrupting my favorite television shows back in the day.

He'd appear uninvited on my TV, looking over the top of his glasses and pursing his lips at the ladies in his grocery store. Two middle-aged women, presumably with high school or college degrees, would be standing in the aisle squeezing rolls of toilet paper. Whipple would wag his finger and primly scold, “Please don't squeeze the Charmin!” After the ladies scurried away, he'd give the rolls a few furtive squeezes himself.

Oh, they were such bad commercials. The thing is, I'd wager if the Whipple campaign aired today, there would be a hundred different parodies on YouTube tomorrow. But back then? All we had was a volume knob. Then VCRs came along and later DVRs, and the fast-forward buttons became our defense. We can now just tell Whipple to shut the hell up, turn him off, and go get our entertainment from any number of other platforms and devices.

To be fair, Procter & Gamble's Charmin commercials weren't the worst thing that ever aired on television. They had a concept, although contrived, and a brand image, although irritating—even to an eighth grader.

If it were just me who hated Whipple's commercials, well, I might shrug it off. But the more I read about the campaign, the more consensus I discovered. In Martin Mayer's book Whatever Happened to Madison Avenue? I found this:

[Charmin's Whipple was] one of the most disliked … television commercials of the 1970s. [E]verybody thought “Please don't squeeze the Charmin” was stupid and it ranked last in believability in all the commercials studied for a period of years….1

In a book called The New How to Advertise, I found:

When asked which campaigns they most disliked, consumers convicted Mr. Whipple … Charmin may have not been popular advertising, but it was number one in sales.2

And there is the crux of the problem. The mystery: how did Whipple's commercials sell so much toilet paper?

These shrill little interruptions that irritated nearly everyone, that were used as fodder for Johnny Carson on late-night TV, sold toilet paper by the ton. How? Even if you figure that part out, the question then becomes, why? Why would you irritate your buying public with a twittering, pursed-lipped grocer when cold, hard research told you everybody hated him? I don't get it.

Apparently, even the agency that created him didn't get it. Advertising veteran John Lyons, worked at Charmin's agency when they were trying to figure out what to do with Whipple.

I was assigned to assassinate Mr. Whipple. Some of New York's best hit teams before me had tried and failed. “Killing Whipple” was an ongoing mission at Benton & Bowles. The agency that created him was determined to kill him. But the question was how to knock off a man with 15 lives, one for every year that the … campaign had been running at the time.3

No idea he came up with ever replaced Whipple, Lyons noted. Whipple remained for years as one of advertising's most bulletproof personalities.

As well he should have. He was selling literally billions of rolls of toilet paper. Billions. In 1975, a survey listed Whipple's as the second-most-recognized face in America, right behind that of Richard Nixon. When Benton & Bowles's creative director, Al Hampel, took Whipple (actor Dick Wilson) to dinner one night in New York City, he said, “It was as if Robert Redford walked into the place. Even the waiters asked for autographs.”

So on one hand, you had research telling you customers hated these repetitive, schmaltzy, cornball commercials. And on the other hand, you had Whipple signing autographs at the Four Seasons.

It was as if the whole scenario had come out of the 1940s. In Frederick Wakeman's 1946 novel The Hucksters, this was how advertising worked. In the middle of a meeting, the client spat on the conference room table and said, “You have just seen me do a disgusting thing. Ugly word, spit. But you'll always remember what I just did.”4

The account executive in the novel took the lesson, later musing, “It was working like magic. The more you irritated them with repetitious commercials, the more soap they bought.”5

With 504 different Whipple toilet tissue commercials airing from 1964 through 1990, Procter & Gamble certainly “irritated them with repetitious commercials.” And it indeed “worked like magic.” Procter & Gamble knew what it was doing. Yet I remain troubled by Whipple. What vexes me so about this old grocer? This is the question that led me to write this book.

What troubles me about Whipple is … he isn't good. As an idea, Whipple isn't any damn good.

He may have been an effective salesman (billions of rolls sold). He may have been a strong brand image. (He knocked Scott tissues out of the number one spot.) But it all comes down to this: if I had created Mr. Whipple, I don't think I could tell my son with a straight face what I did at the office. “Well, son, you see, Whipple tells the lady shoppers not to squeeze the Charmin, but then, then he squeezes it himself… . Hey, wait, come back.”

As an idea, Whipple isn't good. To those who defend the campaign based on sales, I ask, would you also spit on the table to get my attention? It would work, but would you? An eloquent gentleman named Norman Berry, once a creative director at Ogilvy & Mather, put it this way:

I'm appalled by those who [judge] advertising exclusively on the basis of sales. That isn't enough. Of course, advertising must sell. By any definition it is lousy advertising if it doesn't. But if sales are achieved with work which is in bad taste or is intellectual garbage, it shouldn't be applauded no matter how much it sells. Offensive, dull, abrasive, stupid advertising is bad for the entire industry and bad for business as a whole. It is why the public perception of advertising is going down in this country.6

Berry may well have been thinking of Mr. Whipple when he made that comment in the early 1980s. With every passing year, newer and more virulent strains of vapidity have been created. Writer Fran Lebowitz may well have been watching TV when she tweeted, “No matter how cynical I get, it's impossible to keep up.”

Certainly, the viewing public is cynical about our business, due almost entirely to this parade of idiots we've sent onto their screens. Every year, as long as I've been in advertising, Gallup publishes its poll of most and least trusted professions. And every year, advertising practitioners trade last or second-to-last place with used car salespeople and members of Congress.

It reminds me of a paragraph I plucked from our office bulletin board, one of those emailed curiosities that makes its way around corporate America:

Dear Ann: I have a problem. I have two brothers. One brother is in advertising. The other was put to death in the electric chair for first-degree murder. My mother died from insanity when I was three. My two sisters are prostitutes, and my father sells crack to handicapped elementary school students. Recently, I met a girl who was just released from a reformatory where she served time for killing her puppy with a ball-peen hammer, and I want to marry her. My problem is, should I tell her about my brother who is in advertising? Signed, Anonymous

THE 1950S: WHEN EVEN X-ACTO BLADES WERE DULL.

My problem with Whipple (effective sales, grating execution) isn't a new one. Years ago, it occurred to a gentleman named William Bernbach that a commercial needn't sacrifice wit, grace, or intelligence to sell something. And when he set out to prove it, something wonderful happened.

But we'll get to Mr. Bernbach in a minute. Before he showed up, a lot had already happened.

In the 1950s, the national audience was in the palm of the ad industry's hand. Anything advertising said, people heard. Television was brand-new, “clutter” didn't exist, and pretty much anything that showed up in the strange, foggy little screen was kinda cool.

Author Ted Bell wrote, “There was a time when the whole country sat down and watched “The Ed Sullivan Show” all the way through. To sell something, you could go on “The Ed Sullivan Show” and count on everybody seeing your message.”7

World War II was over, people had money, and America's manufacturers had retooled to market the luxuries of life in Levittown. But as the economy boomed, so too did the country's business landscape. Soon there was more than one big brand of aspirin, more than two soft drinks, more than three brands of cars to choose from. And advertising agencies had to do more than just get film in the can and cab it over to Rockefeller Center before “The Colgate Comedy Hour” aired.

They had to convince viewers their product was the best in its category, and modern advertising as we know it was born.

On its heels came the concept of the unique selling proposition, a term coined by writer Rosser Reeves in the 1950s and one that still has some merit. It was a simple, if ham-handed, notion: “buy this product, and you will get this specific benefit.” The benefit had to be one the competition either could not or did not offer, hence the unique part.

This notion was perhaps best exemplified by Reeves's aspirin commercials, in which a headful of pounding cartoon hammers could be relieved “fast, fast, fast” only by Anacin. Reeves also let us know that because of the unique candy coating, M&M's were the candy that “melts in your mouth, not in your hand.”

Had the TV and business landscape remained the same, perhaps simply delineating the differences between one brand and another would suffice today. But then came “advertising clutter”: a brand explosion that lined the nation's grocery shelves with tens of thousands of logos and packed every episode of “I Dream of Jeannie” with commercials for me-too products.

Then, in response to the clutter came “the wall,” which was the perceptual filter we put up to protect ourselves from this tsunami of product information. Many products were at parity. Try as agencies might to find some unique angle, in the end, most soap was soap and most beer was beer.

Enter the Creative Revolution and a guy named Bill Bernbach, who said, “It's not just what you say that stirs people. It's the way you say it.”

“WHAT?! WE DON'T HAVE TO SUCK?!”

Bernbach founded his New York agency, Doyle Dane Bernbach (DDB), on the then-radical notion that customers aren't nitwits who need to be fooled or lectured or hammered into listening to a client's sales message:

The truth isn't the truth until people believe you, and they can't believe you if they don't know what you're saying, and they can't know what you're saying if they don't listen to you, and they won't listen to you if you're not interesting, and you won't be interesting unless you say things imaginatively, originally, freshly.8

This was the classic Bernbach paradigm. From all the advertising texts, articles, speeches, and awards annuals I've read over my years in advertising, everything that's any good about this business seems to trace its heritage back to this man, William Bernbach. And when his agency landed a couple of highly visible national accounts, including Volkswagen and Alka-Seltzer, he brought advertising into a new era.

Smart agencies and clients everywhere saw for themselves advertising didn't have to embarrass itself to make a cash register ring. The national TV audience was eating it up. Viewers couldn't wait for the next airing of VW's “Funeral” or Alka-Seltzer's “Spicy meatball.” The first shots of the Creative Revolution of the 1960s had been fired.*

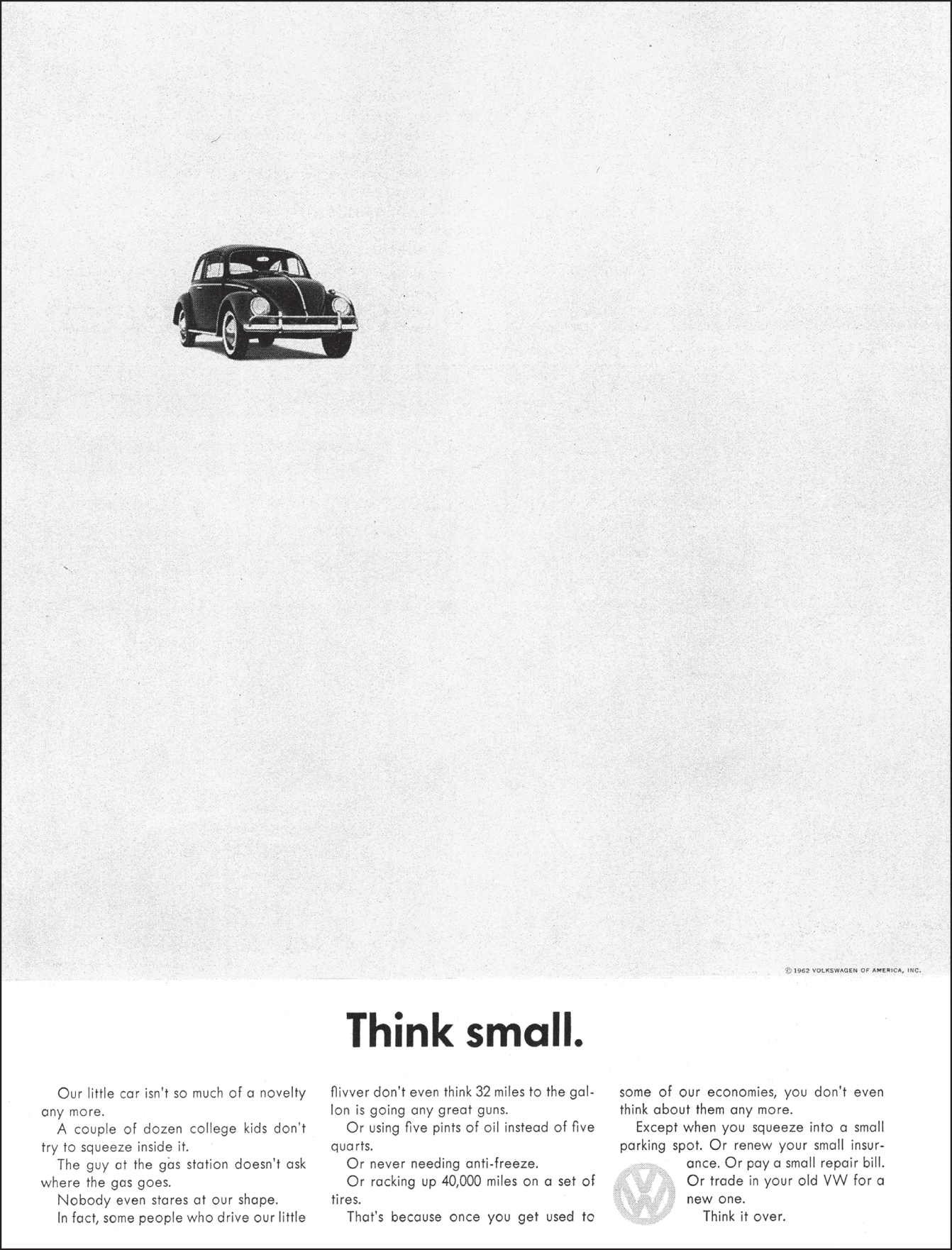

How marvelous to have actually been there when DDB art director Helmut Krone laid out one of the very first Volkswagen ads (Figure 1.2): a black-and-white picture of the simple car, no women draped over the fender, no mansion in the background, and a two-word headline: “Think small.”

Maybe this ad doesn't seem earth-shattering now; we've all seen our share of great advertising. But remember, DDB first did this when other car companies were running headlines such as “Blue ribbon beauty that's stealing the thunder from the high-priced cars!” and “Chevrolet's three new engines put new fun under your foot and a great big grin on your face!” Volkswagen's was a totally new voice.

As the 1960s progressed, the Creative Revolution seemed to be successful, and everything was just hunky-stinkin'-dory for a while. Then came the 1970s. The tightening economy had middle managers everywhere scared.

And the party ended as quickly as it had begun.

THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK.

The new gods wore suits and came bearing calculators. They seemed to say, “Enough of this kreativity krap-ola, my little scribblers. We're here to meet the client's numbers. Put ‘new' in that headline. Drop that concept and pick up an adjective: crunch-a-licious, flavor-iffic, I don't care. The client's coming up the elevator. Chop-chop.”

In Corporate Report, columnist William Souder wrote:

Creative departments were reined in. New ads were pretested in focus groups, and subsequent audience-penetration and consumer-awareness quotients were numbingly monitored. It seemed with enough repetition, even the most strident ad campaigns could bore through to the public consciousness. Advertising turned shrill. People hated Mr. Whipple, but bought Charmin anyway. It was Wisk for Ring-Around-the-Collar and Sanka for your jangled nerves.9

Figure 1.2 Doyle Dane Bernbach's David, about to take on Goliath.

And so after a decade full of brilliant, successful examples such as Volkswagen, Avis, Polaroid, and Chivas Regal, the pendulum swung back to the dictums of research. The industry returned to the blaring jingles and crass gimmickry of previous decades. The wolf was at the door again—wearing a suit. It was as if all the agencies were run by purse-lipped nuns from some Catholic school. But instead of whacking students with rulers, these Madison Avenue schoolmarms whacked creatives with rolled-up research reports like “Burke Scores,” “Starch Readership Numbers,” and a whole bunch of other useless intellectual nonsense.

Creativity was gleefully declared dead, at least by the fat agencies that had never been able to come up with an original thought in the first place. And in came the next new thing—positioning.

“Advertising is entering an era where strategy is king,” wrote the originators of the term positioning, Al Ries and Jack Trout. “Just as the me-too products killed the product era, the me-too companies killed the image advertising era.”10

Part of the positioning paradigm was the notion that the average person's head has a finite amount of space to categorize products. There's room for maybe three. If your product isn't in one of those slots, you must de-position a competitor in order for a different product to take its place. 7UP's classic campaign from the 1960s remains a good example. Instead of positioning it as a clear soft drink with a lemon-lime flavor, 7UP took on the big three brown colas by positioning itself as “The Uncola.”

Ted Morgan explained positioning this way: “Essentially, it's like finding a seat on a crowded bus. You look at the marketplace. You see what vacancy there is. You build your campaign to position your product in that vacancy. If you do it right, the strap-hangers won't be able to grab your seat.”11 As you might agree, Ries and Trout's concept of positioning is valid and useful.

Not surprisingly, advertisers fairly tipped over the positioning bandwagon climbing on. But then a funny thing happened.

As skillfully as Madison Avenue's big agencies applied its principles, positioning by itself didn't magically move products, at least not as consistently as advertisers had hoped. Someone could have a marvelous idea for positioning a product, but if the commercials stank up the joint, sales records were rarely broken.

“Historians and archeologists will one day discover that the ads of our time are the richest, most faithful daily reflections any society ever made of its whole range of activities.”

—Marshall McLuhan

Good advertising, it has been said, builds sales. But great advertising builds factories. And in this writer's opinion, the “great” that was missing from the positioning paradigm was the original alchemy brewed by Bernbach.

“You can say the right thing about a product and nobody will listen,” said Bernbach (long before the advent of positioning). “But you've got to say it in such a way people will feel it in their gut. Because if they don't feel it, nothing will happen.” He went on to say, “The more intellectual you grow, the more you lose the great intuitive skills that really touch and move people.”12

Such was the state of the business when I joined its ranks way back in 1979. What's weird is how the battle between these opposing forces of hot creativity and cold research rages to this hour. And it makes for an interesting day at the office.

As John Ward of England's B&B Dorland noted, “Advertising is a craft executed by people who aspire to be artists but is assessed by those who aspire to be scientists. I cannot imagine any human relationship more perfectly designed to produce total mayhem.”13

PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG HACK.

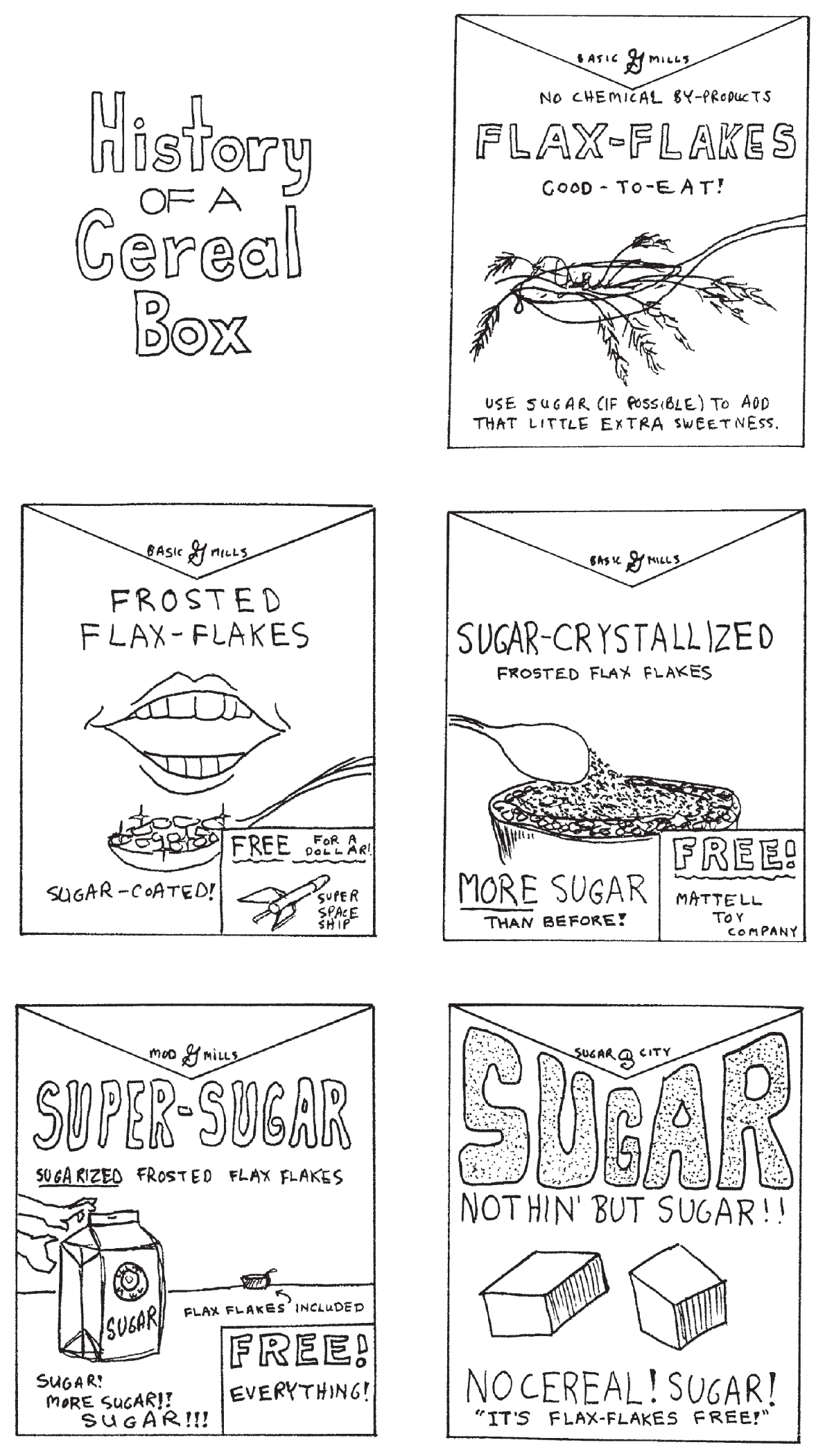

When I was in seventh grade, I noticed something about the ads for cereal on TV. (Remember, this was before the Federal Trade Commission forced manufacturers to call these sugary puffs of crunchy air “part of a complete breakfast.”) I noticed the cereals were looking more and more like candy. There were flocks of leprechauns or birds or bees flying around the bowl, dusting sparkles of sugar over the cereal or ladling on gooey rivers of chocolate-flavored coating. The food value of the product seemed to get less and less important until it was finally stuffed into the trunk of the car and sugar moved into the driver's seat. It was all about sugar.

One morning in study hall, I drew this little progression (Figure 1.3), calling it “History of a Cereal Box.”

I was interested in the advertising I saw on TV but never thought I'd take it up as a career. I liked to draw, make comic books, and doodle with words and pictures. But when I was a poor college student, all I was sure of was I wanted to be rich. I went into the pre-med program, but the first grade on my college transcript (chemistry) was a big, fat, radioactive F. I reconsidered.

Figure 1.3 When I was 12, I was appalled by the stupidity of all the cereal commercials selling sugar and drew this progression of cereal boxes.

I majored in psychology. But after college I couldn't find any businesses on Lake Street in Minneapolis that were hiring skinny chain-smokers who could explain the relative virtues of scheduled versus random reinforcement in behaviorist theory. I joined a construction crew.

When the opportunity to be an editor/typesetter/ad salesperson for a small neighborhood newspaper came along, I took it, at a salary of $80 every two weeks. (Thinking back, I believe I deserved $85.) But the idea of sitting at a desk and using words as a career was intoxicating. Of all my duties at the little newspaper, I found selling ads and putting them together were the most interesting.

For the next year and a half, I hovered around the edges of the advertising industry. I did pasteup for another small newsweekly and then put in a long and dreary stint as a typesetter in the ad department of a large department store. It was there, during a break from setting type about “thick and thirsty cotton bath towels: $9.99,” I first came upon a book featuring the winners of a local advertising awards show.

I was bowled over by the work I saw there—mostly campaigns by Tom McElligott and Ron Anderson from Bozell & Jacobs's Minneapolis office. Their ads didn't say “thick and thirsty cotton bath towels.” They were funny or they were serious—startling sometimes—but they were always intelligent.

Reading one of their ads felt like I'd just met a very likable person at a bus stop. He's smart, he's funny, he doesn't talk about himself. Turns out he's a salesman. And he's selling … ? Well, wouldn't you know it, I've been thinking about buying one of those. Maybe I'll give you a call. Bye. Walking away, you think, nice enough fella. And the way he said things was so … interesting.

Through a contact, I managed to get a foot in the door at Bozell. What finally got me hired wasn't my awful little portfolio. What did it was an interview with McElligott—a sweaty little interrogation I attended wearing my shiny, wide, 1978 tie and where I said “I see” about a hundred times. Tom later told me it was my clearly evident enthusiasm that finally convinced him to take a chance on me. That and my promise to put in 60-hour weeks writing the brochures and other scraps that fell off his plate.

Tom hired me as a copywriter in January 1979. He didn't have much work for me during that first month, so he parked me in a conference room with a three-foot-tall stack of books full of the best advertising in the world: the One Show and Communication Arts awards annuals. He told me to read them. “Read them all.”

He called them “the graduate school of advertising.” I think he was right, and I say the same thing to students trying to get into the business today. Study as much award-winning advertising as you can and read, learn, and memorize. Yes, this is a business where we try to break rules, but as T. S. Eliot said, “It's not wise to violate the rules until you know how to observe them.”

As hard as I studied those awards annuals, most of the work I did that first year wasn't very good. In fact, it stunk. If the truth be known, those early ads of mine were so bad, to describe them accurately I have to quote from Edgar Allan Poe: “A nearly liquid mass of loathsome, detestable putridity.”

But don't take my word for it. Here's my very first ad. Just look at Figure 1.4 (for as long as you're able): a dull little ad that doesn't so much revolve around an overused play on the word interest as it limps.

Rumor has it they're still using my first ad at poison control centers to induce vomiting. (“Come on now, Jimmy. We know you ate all of your gramma's pills and that's why you have to look at Luke's bank ad.”)

The point is, if you're like me, you might have a slow beginning. Even my friend Bob Barrie's first ad was terrible. Bob is arguably one of the best art directors in the history of advertising. But his first ad? The boring, flat-footed little headline read: “Win A Boat.” We used to give Bob so much grief about that, it became his hallway nickname: “Hey, Win-A-Boat, we're goin' to lunch. You comin'?”

There will come a time when you'll just start to get it. When you'll no longer waste time traipsing down dead ends or rattling the knobs of doors best left locked. You'll just start to get it. And suddenly, the ideas coming out of your office will bear the mark of somebody who knows what the hell they're doing.

Along the way, though, it helps to study how more experienced people have tackled the same problems you'll soon face. About mentors, Helmut Krone said:

I asked one of our young writers recently, which was more important: Doing your own thing or making the ad as good as it can be? The answer was “Doing my own thing.” I disagree violently with that. I'd like to pose a new idea for our age: “Until you've got a better answer, you copy.” I copied [famous Doyle Dane art director] Bob Gage for five years.14

The question is, who are you going to copy while you learn the craft? Whipple? For all the wincing his commercials caused, they worked. A lot of people at Procter & Gamble sent kids through college on Whipple's nickel. And these people can prove it; they have charts and everything.

Figure 1.4 My first ad. (I know … I knoooww.)

Bill Bernbach wasn't a fan of charts:

However much we would like advertising to be a science—because life would be simpler that way—the fact is that it is not. It is a subtle, ever-changing art, defying formularization, flowering on freshness and withering on imitation; what was effective one day, for that very reason, will not be effective the next, because it has lost the maximum impact of originality.15

There is a fork in the road here. Mr. Bernbach's path is the one I invite you to come down. It leads to the same place—enduring brands and market leadership—but it gets there without costing anybody their dignity. You won't have to apologize to the neighbors for creating that irritating interruption of their sitcom last night. You won't have to explain anything. In fact, all most people will want to know is, “That was so cool. How'd you come up with it?”

This other road has its own rules, if we can call them that—rules first articulated years ago by Mr. Bernbach and his team of pioneers, including Bob Levenson, John Noble, Phyllis Robinson, Julian Koenig, and Helmut Krone.

Some may say my allegiance to the famous DDB School will date everything I have to say in this book. Perhaps. Yet a quick glance through their classic Volkswagen ads from the 1960s convinces me the soul of a great idea hasn't changed in these years.*

So, with a tip of my hat to those pioneers of brilliant advertising, I offer the ideas in this book. They are the opinions of one writer and the gathered wisdom of smart people I met along the way during a career of writing, selling, and producing ideas for a wide variety of clients. God knows, they aren't rules. As Hall of Fame copywriter Ed McCabe once said, “I have no use for rules. They only rule out the brilliant exception.”

NOTES

- 1. Martin Mayer, Whatever Happened to Madison Avenue? (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1991), 46.

- 2. Kenneth Roman and Jane Maas, The New How to Advertise (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992), 38.

- 3. John Lyons, Guts: Advertising from the Inside Out (New York: Amacom, 1987), 115.

- 4. Frederick Wakeman, The Hucksters (Scranton, PA: Rinehart & Company, 1946), 22.

- 5. Frederick Wakeman, The Hucksters, 45.

- 6. Wall Street Journal, “Stars In Your Eyes: The Wall Street Journal Creative Leaders Series: 1977–1987,” June 1983.

- 7. Phillip Ward Burton and Scott C. Purvis, Which Ad Pulled Best: 50 Case Histories on How to Write and Design Ads That Work (Lincolnwood, IL: NTC Business Books, 1996), 24.

- 8. Bill Bernbach, Bill Bernbach Said … (New York: DDB Needham, 1995).

- 9. William Souder, “Hot Shop,” Corporate Report, September 1982.

- 10. Al Ries and Jack Trout, Positioning: The Battle for Your Mind (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981), 24.

- 11. Ted Morgan, A Close-Up Look at a Successful Agency.

- 12. Bill Bernbach, Bill Bernbach Said . . .

- 13. John Ward, “Four Facets of Advertising Performance Measurement,” in The Longer and Broader Effects of Advertising, ed. Chris Baker (London: Institute of Practitioners in Advertising, 1990), 44.

- 14. Sandra Karl, “Creative Man Helmut Krone Talks About the Making of an Ad,” Advertising Age, October 14, 1968.

- 15. Bill Bernbach, Bill Bernbach Said …

- * You can study these two seminal commercials and many other great ads from this era on YouTube as well as in Larry Dubrow's The Creative Revolution, When Advertising Tried Harder (New York: Friendly Press, 1984).

- * Perhaps the best collection of VW advertisements is a small book edited by the famous copywriter David Abbott, Remember Those Great Volkswagen Ads? (Holland: European Illustration, 1982).