4

A CONTROLLED DAYDREAM: CONCEPTING: COMING UP WITH IDEAS.

BEFORE WE BEGIN, A QUICK NOTE. The first edition of this book came out in 1998—last century, basically. At the time, the possibilities of advertising online were just starting to be realized, and since then the number of media delivering advertising has increased every year.

That said, to begin our discussion of advertising we have to begin somewhere, and so for the purposes of this book, we'll make the humble print ad our starting point. No, it's not interactive, and it doesn't link to other print ads. You don't have to go to LA to make one, and its life usually ends under a puppy. But in its simple two dimensions of white space, it contains all the challenges we need to discuss the entire creative process.

In the little white square we draw on our pads, we'll learn design and art direction. We'll hone our writing. We'll learn how to be information architects—how to move a reader's attention from A to B to C—and these basic skills will stay with us and prove critical as we move from print ads to tweets. As Pete Barry says, “Print is to all of advertising what figure drawing is to fine art; it provides a creative foundation.”1

We'll be talking mostly about the crafts of copywriting and art direction, two infinitely portable disciplines. Everything you learn about writing and art direction here applies to pretty much any surface you'll be working on, from bus sides to computer screens. Yes, there are nuances when it comes to online, writing for search optimization, for example. And later on, we'll get to systems thinking. But overall, copywriting and art direction are the two disciplines someone will need to have when it comes time to make an ad, create a website, or record a radio spot.

Let's begin this part of our discussion with a quotation from Helmut Krone, the man who did VW's “Think Small,” my vote for the industry's first great ad. He said, “I start with a blank piece of paper and try to fill it with something interesting.”

So, if I'm working on a print ad, I generally do the same thing. I get a clean sheet of paper and draw a small rectangle.

And then I start.

GET SOMETHING, ANYTHING, ON PAPER.

Just start.

There's a remarkable book titled The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles. Author Steven Pressfield writes, “It's not the writing part that is hard. What's hard is sitting down to write.” What keeps us from sitting down, he says, is “creative resistance.”2

So, just start.

We've all done it. We say stuff like, “I have to do more research.” “I gotta take care of these emails first.” “I just don't feel inspired.” But these are just rationalizations for why we won't sit down and face the intimidating empty page, what Hemingway called “the white bull.” Author Seth Godin, agrees, and says many people “are creative when they feel like it, but you're only going to become a professional if you can do it when you don't feel like it. And that emotional waiver is why this is … work and not [a] hobby.”

So, just start. Start aggressively. Don't lean back waiting for the muse to alight on your shoulder. Lean into the page. Chase as many ideas as fast and aggressively as you can.

And when you do sit down to work, commit to three-hour sessions. You know you're gonna blow the first 20 minutes talking about some movie you saw on Netflix. But three hours—when you subtract time for bathroom breaks and coffee refills—gives you a solid two to two-and-a-half hours of concepting time.

If you sit for a single hour of concepting time, you might get lucky but it's not likely you'll build up a head of steam. Try to push much past three hours and you'll see diminishing returns.

“Inspiration usually comes during work rather than before it.”

—Novelist Madeleine L'Engle

First, say it straight. Then say it great.

To get the words flowing, sometimes it helps to simply write what it is you want to say. Make it memorable or different later. First, just say it. Flat out.

Try beginning a headline with: “This is an ad about …” And then just keep writing. Who knows? By the time you get to the end of the sentence, you might find you have something just by snipping off the “This is an ad about” part. Even if you don't, you've focused, a good first step. Go for art later. Start with clarity. Start with getting something, anything, on paper.

Create a word and image list.

This is almost always the first thing I do when starting a project. I rope off a couple of pages in my notebook and fill them with words and images that come to mind as I concentrate on whatever project I'm working on. Others call this process “mind mapping” and a quick look at mind map images on Google should explain it almost immediately.

Let's say we're working on a campaign for Evinrude outboard engines. I start a list on the page: Fish. Water. Boat. Two-stroke. Gas guzzler. H2O. Throttle. Flotsam. Jetsam. Atlantic. Titanic. On another page, I sketch any relevant images that float into mind. They could be memes, symbols, visual concepts, anything connected to the product or category.

Think of these words and images as the molecular building blocks of ideas. Stare at them. Wait for things to happen. They will.

Dig shallow holes everywhere.

The information in the creative brief is full of advice on where we ought to dig to find the best answer. Added together—the strategy, target audience, message—they all serve to direct our focus to a certain area, like it's this one square acre where it's likely the answers will be found.

But instead of digging up the entire acre, we dig shallow little holes all over the place. Like little creative tests. In the beginning of any creative process, it's important to try a wide variety of different approaches.

In Rethink the Business of Creativity, the authors give us this advice:

Don't waste your time and energy digging deep until you've uncovered a shiny nugget or two. In advertising terms, this means doing a wide initial exploration, testing out various insights. Against simple executions such as a billboard, a tagline, or a script. Quick sketches of your ideas are all you need during the beginning of the creative process. For an artist it could mean doing many pencil sketches before putting paint to canvas. You're looking for proof-of-concept at this shallow hole stage—just enough validation to know it could be worth it to dig [deeper here].3

Even if you do happen to find a gold nugget or two, don't stop the search to set up camp around one promising find. Resist the urge to rush to the computer and start polishing. Just capture the concept on paper and keep digging.

At the beginning of the creative process, it's important to try a wide variety of different approaches.

Allow yourself to come up with really terrible ideas that are no good at all.

In Bird by Bird, Anne Lamott's book on the art of writing fiction, she says:

The only way I can get anything written at all is to write really, really crappy first drafts. That first draft is the child's draft, where you let it pour out and then let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later. You just let this childlike part of you channel whatever voices and visions come through and onto the page. If one of the characters wants to say, “Well, so what, Mr. Poopy Pants?,” you let her.4

Same thing in advertising. Start with some flat statement like “Sale ends Saturday” and just go from there. If it sounds like I'm asking you to write down bad ideas, I am; there's something liberating about writing them down. It's as if doing so actually flushes them out of your system.

Many of us resist this advice, out of vanity, I think. We simply cannot picture our fine selves writing down anything that doesn't quiver and glow with brilliance. Why? Because this is a brand-new note pad, we think. Only great stuff should be written here. But then we remember, a sheet of paper costs about a squillionth of a cent. It's a workbench, not a roped-off area at the Louvre. Scribble away. Keep writing. Don't stop.

Work fast. Fail faster.

I'll wager any aspiring copywriter reading this book can write a beautiful headline. I'll also bet that if this aspiring copywriter and I were to race, I'd probably manage to write a beautiful headline first.

With years of experience under my ever-widening belt, I know how to fail faster than juniors. I know when to abandon an approach that's not working. I know how to pick up an idea in my head, inspect its possibilities, and decide quickly: keep it, drop it. I can come up with 50 really horrible ideas in the time it takes a junior to get 10. The quantity of ideas I'm able to produce in a given amount of time increases the odds I'll strike quality sooner.

All creativity is an iterative process. We start off by making a sketch of an idea. Then we cock our heads at it, see a possible way to improve it, and sketch it a different way. Then we sketch another improvement, then another. There's a saying: “All art is a series of recoveries from the first line drawn.”

In Chasing the Monster Idea, Stefan Mumaw discusses failure: “Figuring out how to master this process of failing fast and failing cheap and fumbling toward success is probably the most important thing companies have to get good at.”5 Writer Jena McGregor agrees, calling it “getting good at failure.”

At a SXSW Interactive seminar I chaired, most folks in the audience agreed failure is practically a federally required ingredient of creativity. You have to risk a belly flop, particularly in the online space, where a sense of play is important. And part of play is failure: the skinned knee, the black eye. Everyone at the seminar, to a person, said to push past the pain and “fail forward, fail harder, fail gloriously.” Whatever flavor of fail you get, our group said, get up, walk it off, and go at it again.

“The trick is to go from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm.”

—Winston Churchill

Interpret the problem using different mental processes.

If there was a boot camp for ad creatives, it would probably be this section where we talk about basic “concepting techniques”—a fancy term that refers to all the different ways you can screw around with words and images to make something cool, which is basically what concepting is.

The list that follows is just some of the techniques that come to mind. There are other lists you can study. Mario Pricken, author of Creative Advertising, created a pdf you can Google titled Kick Start: A Methodology for Producing Ideas. And online there's also a wonderful site called DeckofBrilliance.com.

| Use visuals only | With product | Substitute |

| Use words only | Without product | Combine |

| Omit | Before and after | Separate |

| Understate | Simulate | Reframe |

| Contemporize | Use the medium | Invert |

| Symbolize | Change perspective | Transpose |

| Abstract | Eliminate | Distort |

| Compare | Focus | Rotate |

| Metaphor | Dissect | Distort |

| Passage of time | Repetition | Exaggerate |

Think of each technique on the list as a sort of lens through which you can shoot the main message you want to communicate. At first it will feel clumsy pausing to pick up each one of these different lenses, but after a while you get used to it, and soon you'll be able to do it without thinking about it.

So, take your main message and start processing it through these different filters. Come at the problem from wildly different angles. George Felton asks, “How many different solutions can you find—and how quickly? Are you able to see a problem from multiple points of view? How dissimilar are your ideas from each other? Can you leap around or is each idea just a logical half-step from the last?”6 Don't keep sniffing all four sides of the same fire hydrant. Run like a crazed dog through entire neighborhoods.

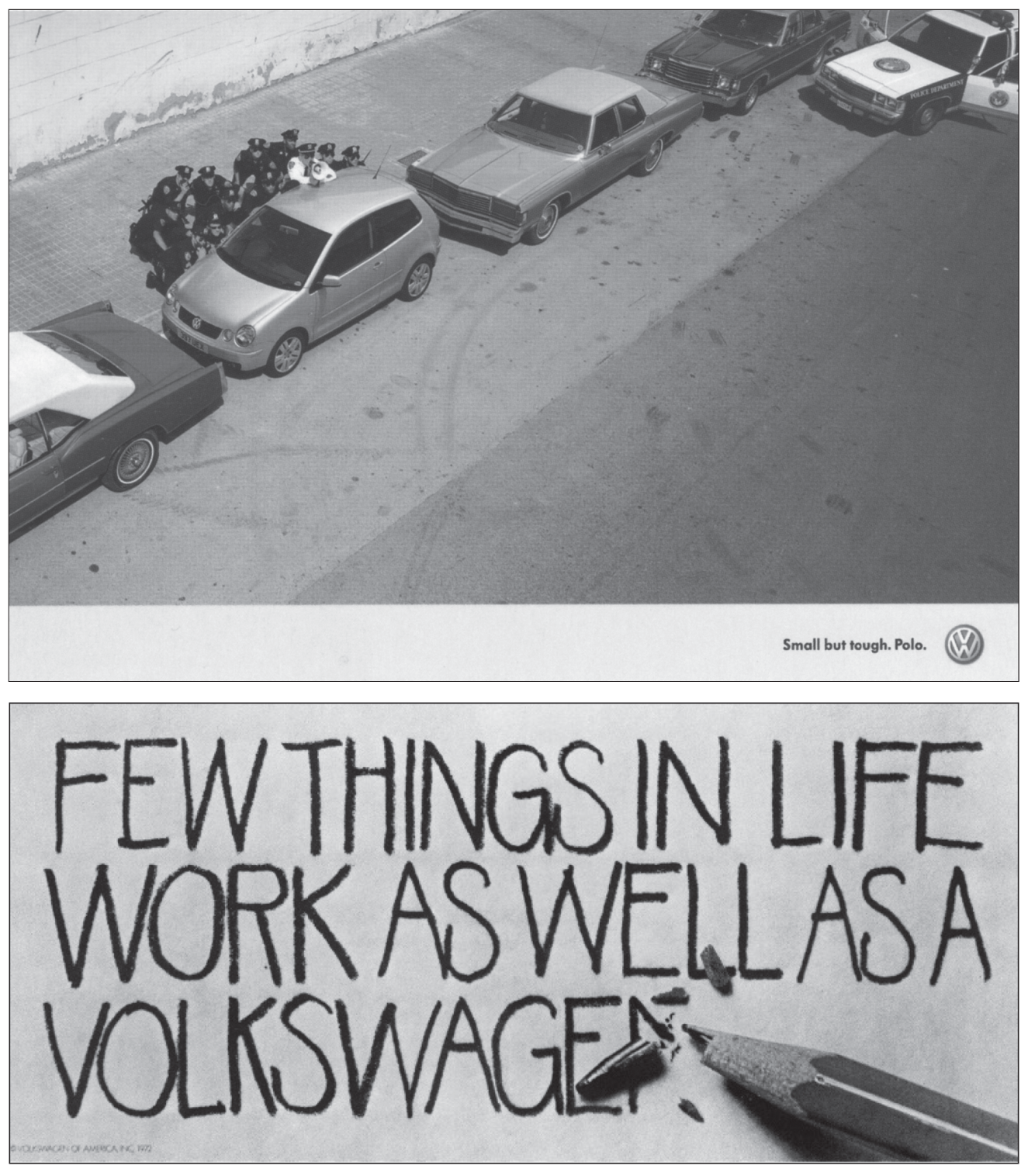

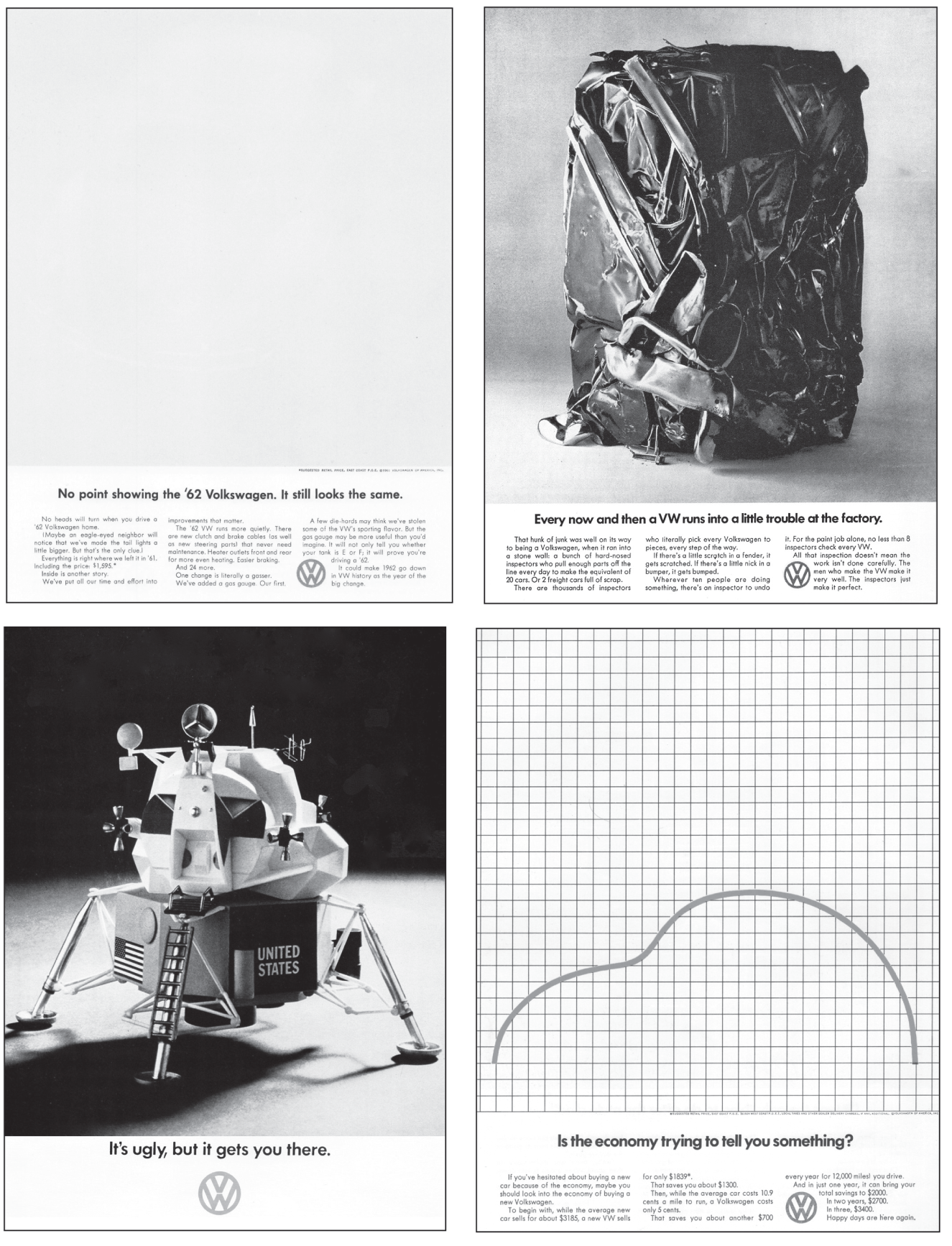

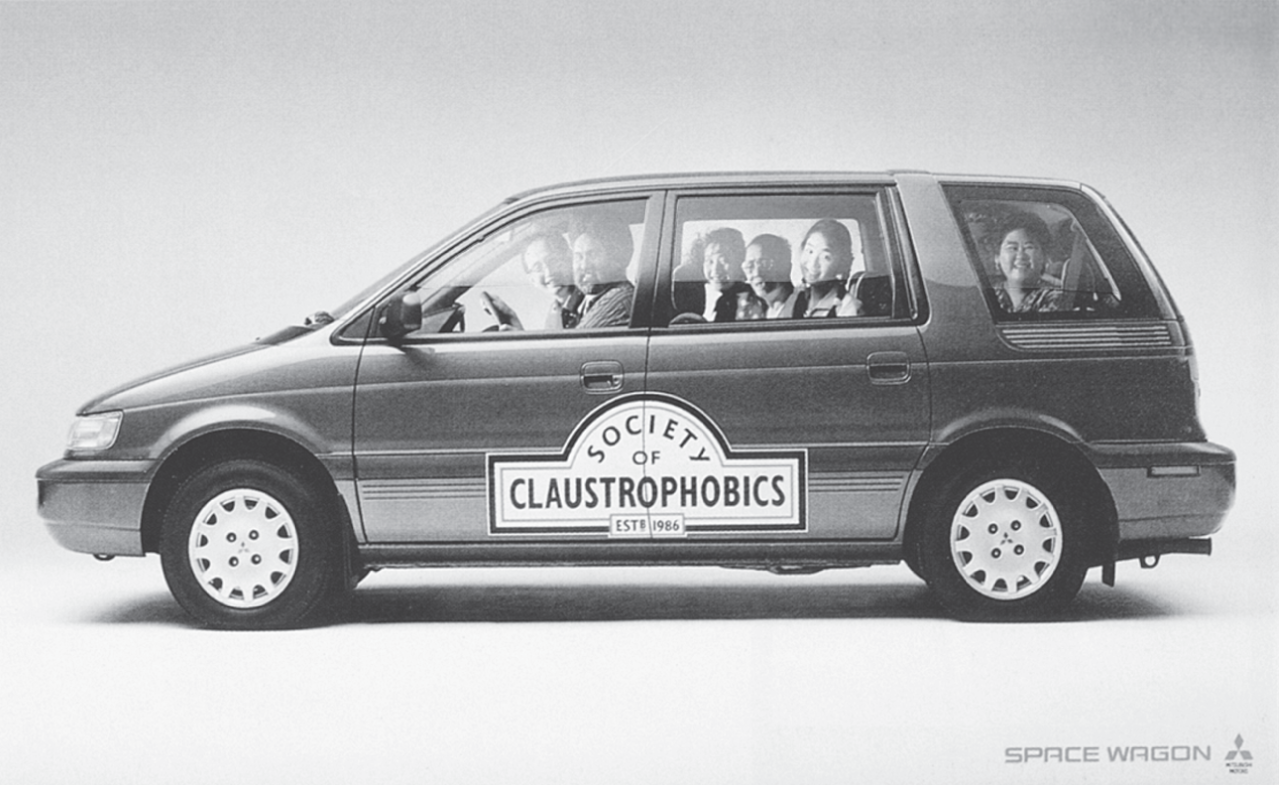

On the next couple of pages, you will see a variety of famous Volkswagen ads that reflect some of these techniques (Figures 4.2–4.4). Except for the first and last examples, all were created by Doyle Dane Bernbach in the ’60s.

Figure 4.2 A visually dominant ad for VW and a copy-driven one.

Think it through before you settle for the ol' exaggeration thing.

I put the “exaggerate” technique at the end of that list of concepting approaches because it's used so commonly. Granted, there are great ideas out there using exaggeration to good effect. I'm just sayin' exaggeration is too often the first concepting techniques junior creatives apply.

Say you're doing an ad for a water heater. The exaggeration technique's first 100 ideas will be knee-jerk scenarios about how cold the water will be if you don't buy this water heater: “What if we had, like, ice cubes coming out of the water faucet. See? ’Cause it's so cold, the water faucet will have like ice cubes, right? Ice cubes, man … 'cause … 'cause the water's like really cold.”

Figure 4.3 Clockwise from top right: Omission, understatement, using symbols, and contemporizing.

Figure 4.4 Clockwise from top right: Comparison, metaphor, and abstraction.

- Buy a lottery ticket and you'll be so rich that ______________. (Fill in with I'm-really-rich jokes here.)

- Buy this car and you'll go so fast that ______________. (Insert cop-giving-ticket jokes here.)

It's just a little too easy. I'm not saying it's off-limits. Just be aware when you're using it. Pete Barry further cautions if you're going to do an exaggeration scenario, make sure you base it on a truth; otherwise, you have only a silly contrivance—as in this cousin of the exaggeration technique Teressa Iezzi identified in The Idea Writers: “I'm so distracted by the awesome nature of this product that I didn't notice (INSERT OUTRAGEOUS VISUAL PHENOMENON HERE!!).”7

A tired old idea to which we say, “Meh.”

Go in the opposite direction.

Look at what every other brand in your category is doing and then go the other direction. They're using film and photography? Try painting. They're running their campaigns on social platforms. Try outdoor.

You can also try considering the opposite of the product itself. What doesn't your product do? Who doesn't need the product? When is the product a waste of money? Study the inverse problem and see where the opposite thinking leads.

Tom Monahan calls this “180˚ thinking.” Recently, I saw a great 180˚ idea in a student portfolio. It was a small poster for a paint manufacturer that painters could leave after a job was finished. Above the company's logo, the warning read: “Dry Paint.”

Spend some time away from your partner, thinking on your own.

I think many teams prefer to start this way. It gives both of you a chance to look at the problem from your own perspectives, before you each bring your ideas to the table.

Share your ideas with your partner, especially the kinda dumb ones.

Just because an idea doesn't work yet doesn't mean it might not work eventually. I sometimes find I get something that looks like it might go somewhere, but I can't do anything with it. It just sits there. Some wall inside prevents me from taking it to the next level. That's when my partner scoops up my miserable little half-idea and runs with it over the goal line.

Remember, the point of teamwork isn't to impress your partner by sliding a fully finished idea across the table. It's about how 1 + 1 = 3.

That said, I also remind you not to say aloud every stinking thing that comes into your head. It's counterproductive. I worked with someone like this once, and—in addition to trying to concept in a state of irritation—I ended up with a bad case of “idea-rrhea” that lasted the whole weekend.

Allow your partner to come up with terrible ideas. Don't play devil's advocate.

Being the devil's advocate is a fine role to take when road-testing an idea before taking it to a client. But it has no place in the early part of the creative process. Instead, do what writing coach Sydney Shore suggests: play the “angel's advocate.” Ask: What is good about the idea? What do you like about it? Coax the little guy along.

It's worth noting here, too, the quickest way to shut down your partner's contribution to the creative process is to smirk or roll your eyes at a bad idea. Never. Ever. Do. This. Even if the idea truly and most sincerely blows, just say, “Hmmm … that's interesting” and move on.

Take whatever your partner puts out and toss it back with your spin on it. In Creative Advertising, author Mario Pricken likens this conceptual back-and-forth to a game: “a kind of ping-pong ensues, in which you catapult each other into an emotional state resembling a creative trance.”8

Let your subconscious mind do it.

Where do ideas come from? I have no earthly idea.

In 1900 or so, a writer named Charles Haanel said true creativity comes from “a benevolent stranger, working on our behalf.” Novelist Isaac Singer said, “There are powers who take care of you, who send you patience and stories.” And film director Joe Pytka said, “Good ideas come from God.” I think they're probably all correct. It's not so much our coming up with great ideas as it is creating a canvas where a painting can appear.

So do what Marshall Cook suggests in his book Freeing Your Creativity: “Creativity means getting out of the way… . If you can quiet the yammering of the conscious, controlling ego, you can begin to hear your deeper, truer voice in your writing, … [not the] noisy little you that sits out front at the receptionist's desk and tries to take credit for everything that happens in the building.”9

Stop the chatter in your head. Breathe from your stomach. Ask, what does the ad want to say? Not you, the ad. In The Creative Companion, David Fowler says, “Maybe if you walked around the block you could hear it more clearly. Maybe if you went and fed the pigeons, they'd whisper it to you. Maybe if you stopped telling it what it needed to be, it would tell you what it wanted to be. Maybe you should come in early when it's quiet.”10

Try it. Just shut up. Listen.

In The Creative Process Illustrated, Griffin and Morrison quote ad veteran Jim Haven on his process:

I have a feeling that creativity usually happens on the side of your thoughts rather than the front or the back. It's a non-linear by-product of thinking about something logically. You can't logic creativity. You can't even make creativity. You can only hope to replicate the process in which creativity might develop, like a petri dish for your thoughts. To me, it's like flexing a muscle and relaxing. The relaxing is where the magic happens.11

As you can see, it's hard to describe exactly what this “concepting” business is. Here is the venerable Dan Wieden's attempt: “To me, there's always a sense of you're not creating something, but that you're in a dialogue with the work itself and you need to listen to the work and respond to what it's saying.” Wieden goes on: “You can't be pushing it all the time, because then you delude yourself. You need to somehow have this ‘conversation' with it. You're in communication with something and pulling it up out of nonexistence into existence.”12

Man, pulling stuff out of nonexistence sounds like a fun job.

Low-hanging fruit, the barren wasteland, and eureka.

At the beginning of the creative process, beware of the Valley of Low-Hanging Fruit. As you first wander through this fabled forest, you will probably feel like an advertising genius. Because you'll be grabbing ideas left and right with ease. Wow, this is so easy, you think, as you pluck ready-made ideas, fully formed, one after another off the boughs.

But here's the thing about early ideas that come quickly: they're easy. Too easy. Pretty much any- and everybody else who's working the same problem will see these same easy solutions. The smart thing to do here is to simply write down every too-easy idea and move on. Maybe later you'll be able to convert it into something new and interesting.

The next phase of the creative process is everybody's least favorite. I'll call it the Barren Wasteland. I'm talking about those periods when you simply have no usable ideas. Every single thing you come up with sucks. The ideas slow to a trickle and stop. The crickets begin to chirp and tumbleweed rolls through the wide, empty space between your ears and all you can do is stare at the wall.

Other than gutting it out, there's no secret to getting through a wasteland. Periods like this simply happen on every creative journey and professionals get used to them. As we noted previously, in James Webb Young's classic paradigm for idea development, the wasteland is simply his step 3: the part where your subconscious is also wrestling with the problem. I mention Young here because we must get through this step to get to his step 4: the a-ha moment. Problem is, eureka! arrives only after a long slog through the barren wasteland.

Get coffee. Strap in.

A FEW WORDS ABOUT PICTURES.

Can the solution be entirely visual?

The screen saver on the computers at London's Bartle Bogle Hegarty reads, “Words are a barrier to communication.” Creative director John Hegarty says, “I just don't think people read ads.”

There's a reason they say a picture is worth a thousand words. When you first picked up this book, what did you look at? I'm betting it was the pictures.

Granted, if you interest readers with a good visual or headline, yes, they may go on to read your copy. But the point is, visuals work fast. As the larger brands become globally marketed, visual solutions become even more important. They translate, not surprisingly, better than words.

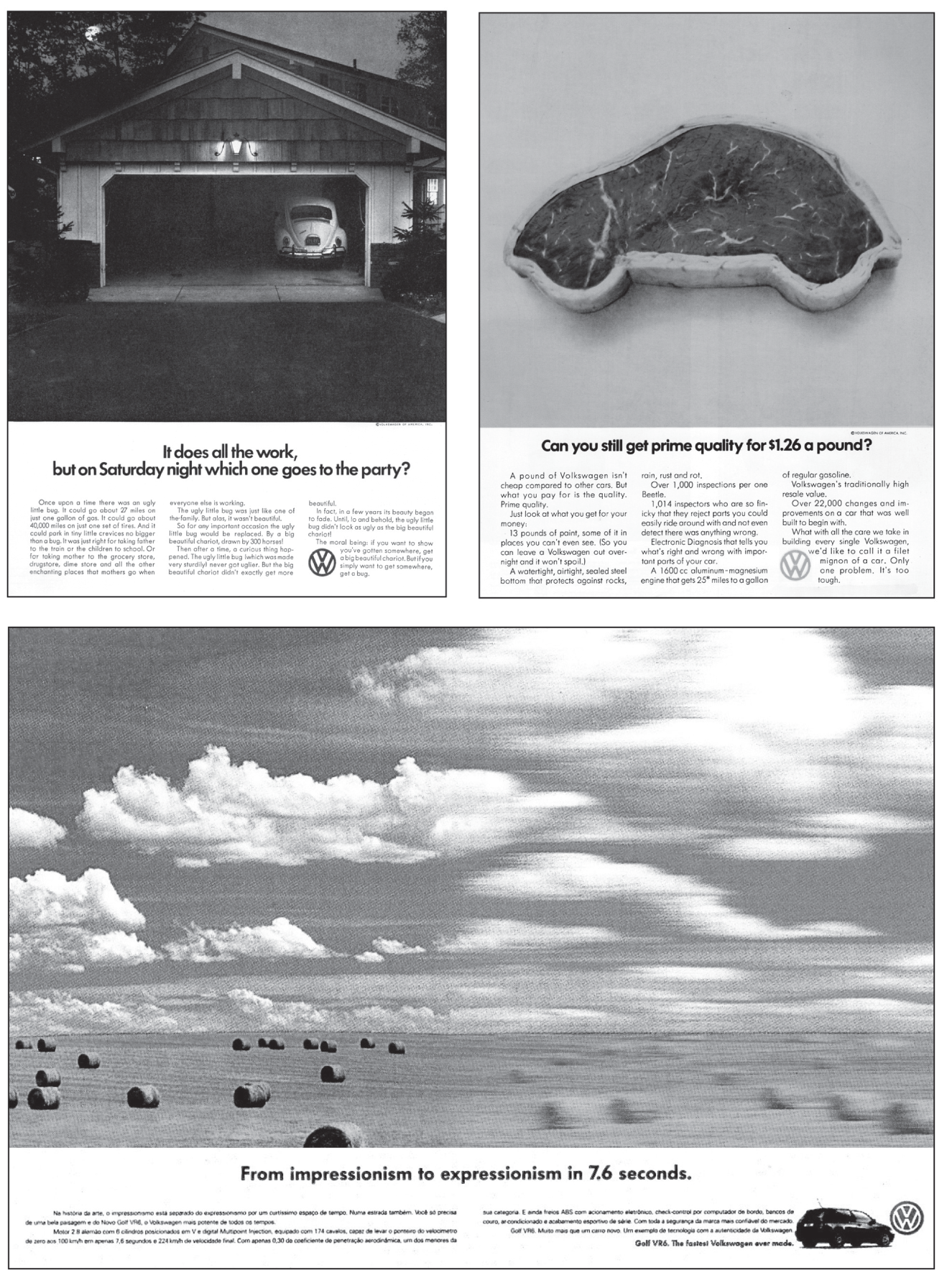

The ad for Mitsubishi's Space Wagon (Figure 4.5) from Singapore's Ball Partnership is one of my all-time favorites. The message is delivered entirely with one picture and a thimbleful of words. What could you possibly add to or take away from this concept?

Figure 4.5 Long-copy ads can be great. This is not one of them.

Relying on the image means it assumes added responsibilities; it has to carry the idea. You can't bury your main selling idea down in the copy. If readers don't get what you're trying to say from the visual, they won't get it and will move on. You have to bake the main selling idea right into the visual.

Can your brand own something visual?

You've got to find something your client can call their own: a shape, a color, a design—something unique.

Helmut Krone: “I was working on Avis and looking for a page style. That's very important to me, a page style. I think you should be able to tell who's running an ad at a distance of twenty feet.”13

What's interesting about Krone's statement is he's not talking about billboards but print ads. And if you look at his two most famous campaigns, they stand up to the test. You could identify his Volkswagen and Avis ads from across a street (Figure 4.6).

The longer I'm in this business, the more I'm convinced art direction is where the major battle for brand building happens. Once you establish a look, once you stake out a design territory, no one else can use it without looking like your brand. The Economist practically owns the color red. And Apple's signature color of white in its stores and all its packaging fairly screams “Apple.”

Figure 4.6 DDB art director Helmut Krone said the Avis look came from a deliberate reversal of the VW look. VW had large pictures, Avis, small. VW had small body type, Avis, large. Note the absence of an Avis logo.

Own something visual.

Coax an interesting visual out of your product or its benefit.

Many years ago, when he was a little boy, my son Reed and I were playing, and we stumbled on a fun mental exercise using his toy car.

I held the car in its traditional four-wheels-to-the-ground position and asked him, “What's this?” “A car,” he said. I tipped it on its side. Two wheels on the ground made the image a “motorcycle.” I tipped the car on its curved top. He saw a hull and declared it a “boat.” When I set it tailpipe to ground, pointing straight up, he saw propulsion headed moonward and told me, “It's a rocket!”

Look at your product and do the same thing. Visualize it on its side. Upside down. Make its image rubber. Stretch your product visually six ways to Sunday, marrying it with other visuals, other icons, and see what you get—always keeping in mind you're trying to coax out of the product a dramatic image with a selling benefit.

What if it were bigger? Smaller? On fire? What if you gave it legs? Or a brain? What if you put a door in it? What is the perfectly wrong way to use it? What other thing does it look like? What could you substitute for it?

Take your product, change it visually, and by doing so dramatize a customer benefit.

Get the visual clichés out of your system right away.

Somewhere out there is the Home for Tired Old Visuals. Sitting there in rocking chairs on the porch are visuals like Uncle Sam, a talking baby, and a proud lion, just rocking back and forth waiting for someone to come use them in ads once again. (“When we were young, we were in all kinds of ads. People used to LOVE us.”)

Remember: every category has its version of tired old visuals. It's like the Valley of Low-Hanging Fruit, with pictures. In insurance, it's grandfathers flying kites with grandchildren. In the tech industries, it's earnest people wearing glasses in which you can see the reflection of their computer screen. Learn what iconography is overused in your category, and then … don't do that.

Check out this ad for Head golf clubs (Figure 4.7) No greenways. No golf stars. Imagine how it stood out in all the golfing pubs it ran in.

Figure 4.7 I like how the creative team pictured a sledge hammer and not some Tired Old Visual, like two old white guys on the green high-fiving each other.

Metaphors must've been invented for advertising.

They aren't always right for the job, but when they are, they can be a quick and powerful way to communicate. Shakespeare did it: “Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?”

In my opinion (and the neo-Freudian Carl Jung's), the mind works and moves through and thinks in and dreams in symbols. Red means anger. A dog means loyal. A hand coming out of water means help. Ad people might say each of these images has “equity,” something they mean by dint of the associations people have ascribed to them over the years. You may be able to use such equity to your client's advantage, particularly when the product or service is intangible such as, say, insurance. A metaphor can help make it tangible.

What makes metaphors particularly useful to your craft is they're a sort of conceptual shorthand and say with one image what you might otherwise need 20 words to say. They get a lot of work done quickly and simply.

The trick is doing it well. Just picking up a meme or some prepackaged image and plopping it down next to your client's logo won't work. But when you can take an established image (for example, a mime), put some spin on it, and use it in some new and unexpected way that relates to your product advantage, things can get pretty cool. VW does this in Figure 4.8, elegantly suggesting how quiet the ride in a new Golf is.

Verbal metaphors can work equally well. I remember a great ad from Nike touting their athletic wear for baseball. Below the picture of a man at bat, the headline read, “Proper attire for a curveball's funeral.” In Figure 4.9 another verbal metaphor is put to good use to describe the feeling of flooring it in a Porsche.*

Remember, something has to dominate the page.

Whether it's a big headline, a large visual, or a single word floating in white space, somebody's got to be the boss.

Every design needs a boss. There needs to be an overall visual hierarchy, an implied order of the relative importance of the elements of the whole. The late Roy Grace, one of the famous art directors from Doyle Dane Bernbach, wrote on this issue:

Figure 4.8 Metaphor as ad. Mimes = quiet.

Figure 4.9 Verbal metaphors work just as well as visual ones.

There has to be a point on every page where the art director and the writer want you to start. Whether that is the center of the page, the top right-hand corner, or the left-hand corner, there has to be an understanding, an agreement, and a logical reason where you want people to look first.14

“Do I want to write a letter or send a postcard?”

In his book Cutting Edge Advertising,15 Jim Aitchison offers up this early fork in the road: do you want to write a letter or just drop a postcard?

Do you have a lot of information to impart or is it just one thought? Picture a sliding scale, with an all-visual idea on one side and all-verbal idea on the other. What's the right mix for your product and your message? Remember, something must dominate.

A postcard, says Aitchison, is an idea that's visually led. A single visual and sometimes a small bit of copy is all that are needed to make the point. Volkswagen's Golf ad with the mimes is a postcard. Figure 4.10 is another good example of a postcard from Land Rover via its Chinese agency, Y&R Beijing.

However, a letter is an ad that's predominantly copy-driven. It's probably better for ideas that have to deliver a more complex message. Just the sheer weight of the body copy adds a sense of gravitas to the product regardless of whether the reader takes in a word of the copy. Here's another ad for Land Rover, this one done by my friends at GSD&M (Figure 4.11).

Figure 4.10 Land Rover's postcard ad. In terms of brand = adjective, I'd say Land Rover = adventure.

You'll see both letter ads and postcard designs throughout this book. Give special attention to how each visual or verbal format serves the different messages the brands are trying to convey.

Can you use the physical environment as your visual?

Sometimes the very place your idea appears can become the “visual” for the concept. This mixture of medium and message happens frequently in ads placed in what media people call “ambient media.” There are hundreds of possibilities typically for sale in any urban environment: hanging straps on subway cars, the handle of a grocery cart, or on back of the receipt when you check out.

When the editorial environment is right, this also works in print. One of my all-time favorites was delivered on the back cover of my Rolling Stone magazine (Figure 4.12). The headline's a little small here, but it reads: “Cover shot with Portrait mode on iPhone 7 Plus.” Ad as demonstration. Brilliant.

Figure 4.11 “If we've learned one thing in 30 years of building Range Rovers, it is this. An ostrich egg will feed eight men.” Followed by 630 words of Gold One Show body copy.

Figure 4.12 The headline on the back of the magazine reads: “Cover shot with Portrait mode on iPhone 7 Plus.”

Show, don't tell.

Telling people something is never as powerful as showing them. The iPhone ad shows us. And because it's not telling us, the ad didn't need a clever headline. The classic ad by BMP London for Fisher-Price's anti-slip roller skates is another great example (Figure 4.13).

Avoid style. Focus on substance.

Remember, styles change; typefaces and design and art direction, they all change. Fads come and go. But people are always people. They want to look better, make more money, feel better, be healthy. They want security, attention, and achievement. These things about people aren't likely to change.

So, focus your efforts on speaking to these basic needs, rather than tinkering with the current visual affectations. Your art direction is about more than looking up-to-date. It's about concentrating on the soul of an idea instead of the width of its lapels. Riding the wave of every passing fad will make your work look trendy and derivative. Pull the look out of the DNA of the brand and focus instead on the substance of what you want to communicate.

Figure 4.13 The mental image this ad paints of two kids landing on their bums is more powerful than actually showing them that way.

CHASING A CAMPAIGN IDEA.

Pick a small customer contact point and then think big.

We've used print as a great starting point to talk about concepting. Now it's time to apply that creative thinking free of form.

Think back to the exercise we talked about in the last chapter, where we imagined a day in the life of the customer. Consider where your brand and a customer might run into each other during the day. What opportunities jump out at you? Find one that intrigues you and play with it.

In Laurence Minksy's book How to Succeed in Advertising When All You Have Is Talent, Weiden's Susan Hoffman put it this way:

Think holistically… . [What] would you do in the store? How can you pull the iconography of the campaign right into the clothing hang tag? A coupon? Online? The best work has legs to go everywhere and puts a strong, consistent, visual imprint on every consumer touch point. It's important to bring this kind of thinking to your work… . Take this inventiveness and apply it to the business. But do more than just ads. Produce an album, experiment with graffiti, invent a new product, shoot a film, or write a book.16

Think creatively about different media where your message can appear. Look for possible customer contact points with the customer. For instance, the inside bottom of a paper coffee cup might be a good place to put a message about sweeteners. Maybe a dingy subway car is just the place to tell a glassy-eyed commuter she might like a week in St. Thomas. If your client is an organization for some social issue, why not projection map your idea all over the building across from city hall? (A British agency projected a provocative ad directly onto Houses of Parliament.)

Creating campaign executions isn't a matter of copying and pasting a print ad onto a billboard and a website. To fully realize the possibilities of a multimedia campaign, you'll need to drag your main idea through each medium and start from scratch when you get there. Leverage the unique strengths of outdoor's scale; of online's ability to let users interact with a brand; of video's film, sound, music, and visual storytelling.

The challenge is to make your product look totally cool in each medium and then, at the end of the day, have your overall campaign and the overall experience hang together with one consistent look, one consistent narrative.

Once you get on a streak, ride it.

The famous scientist Linus Pauling said: “The best way to get a good idea is to get a lot of ideas… . At first, they'll seem as hard to find as crumbs on an oriental rug. Then they start coming in bunches. When they do, don't stop to analyze them; if you do, you'll stop the flow, the rhythm, the magic. Write each idea down and go on to the next one.”

When the words finally start coming, stay on it. Don't break for lunch. Don't put it off ’til Monday. You'd be surprised how cold some trails get once you leave them for a few minutes.

Make sure every piece in the campaign makes sense all by itself.

You are not in control of when or where a customer runs into your campaign. It's not like you're walking a customer through your portfolio and you get to say, “Okay, we kick off the campaign with this piece.” Every single element must be completely understandable, whole, in and of itself. Kinda like how each cell contains the DNA for the whole organism. (Sorry. Got deep there for a sec.)

Work. Don't talk. Work.

Don't talk about the concepts you're working on. Talking turns energy you could use to be creative into talking about being creative. It's also likely to send your poor listener looking for the nearest espresso machine because an idea talked about is never as exciting as the idea itself. If you don't believe me, call me up sometime and I'll describe the movie Inception to you.

Work. Just work. The time will come to unveil. For now, just work. The best ad people I know are like ninjas, silent and deadly. You never hear them out in the hallways talking about their ideas. They're working.

I saw a cool bumper sticker the other day: “Work hard in silence. Let success be your noise.”

Come up with a lot of ideas. Cover the wall.

It's tempting to think the best advertising people just peel off great campaigns 10 minutes before they're due. But that is perception, not reality. My friend, Jay Russell, told me when he was at Crispin Porter + Bogusky, he remembers looking at more than 2,000 ideas—polished, worked-out ideas—for a Microsoft Android campaign. He said the pile of ideas stacked in the corner of his office came up to his waist.

More often, these piles of ideas are tacked up in an agency conference room somewhere. During a new business pitch, agencies will often call it the War Room. But you can create your own version, whether on a wall or digitally, using something like Canva or Figma.

Once you've come up with hundreds of ideas, this is where the cool part happens.

“Creativity is allowing yourself to make mistakes. Art is knowing which ones to keep.”

—“Dilbert” cartoon creator, Scott Adams

Write hot. Edit cold.

Get it on paper, fast and furious. Be hot. Let it pour out. Don't edit anything when you're coming up with the ads. Then, later, be ruthless. Cut everything that's not A-plus work. Put all the A-minus and B-plus stuff off in another pile you'll revisit later. Everything B-minus or down, either kill or put on the shelf for emergencies.

Review all the ideas so far and look for patterns.

Once you've “edited cold” and thinned the herd to your very favorite pieces, stand back and look at the collection.

When you put them all up somewhere for viewing, you'll see some ideas overlap a bit or share a trait with others: maybe it's a visual similarity, maybe verbal, or they might group by medium—interactive, video, outdoor. Reposition similar ideas on your wall to form clusters and then stand back and keep looking for other patterns. This process is important and here's why.

Patterns are campaigns trying to come to life.

This part of the process is called convergent thinking, a term used to describe thought focused on finding a single answer to a problem—in this case, a pattern. Basically, it's like we've spread a big handful of pearls on the table and now we're looking for a thread; that one narrative thread that can tie all the separate pearls into one necklace.

Let's say we do find a pattern. Maybe it's only two ideas, but it's clear they “belong together.” So, for now let's pretend these two ideas represent our main idea. Here is where we throw the gears in reverse and do the opposite of convergent thinking.

In divergent thinking, we take this main idea (the two concepts we just grouped together) and start pulling other ideas out of it. We're trying to add brothers and sisters to the original two ideas. At the agency Rethink, they refer to divergent thinking as a “Deep Dig.”

The Shallow Holes process is like digging six inches deep in a sandbox. [Now] it's time to drill down three hundred feet… . The Deep Dig takes that basic thinking and applies it everywhere the brand connects with people. This means both traditional and new media, but it also extends far beyond advertising, like experiential “stunts,” store design, uniforms, customer experience, internal communications, staff development tools, even product ideas.17

Okay, so let's say we do a Deep Dig and chase a particular idea with some divergent thinking. Although we may indeed strike oil and find our campaign, there's always the possibility we don't. Sometimes an idea that looks huge resists our attempts to enlarge it, to stretch it. That's when we go back to digging shallow holes, to creating more ideas.

In convergent thinking, we group possibilities; in divergent thinking, we create them. The process repeats itself, going back and forth between the two modes of thought.

Patterns are campaigns trying to come to life.

Ultimately, what you're looking for is a campaign. Most brands live in campaigns, which are released over time like chapters in a brand's story. When done well, every campaign clarifies a brand's purpose in the world and strengthens its connection to customers.

When you first start at an agency, it's likely you'll be asked only to add to campaigns, not create them. But as you grow, you'll be expected to come up with entire campaigns.

In my era—The Paleozoic? you ask. You funny.—we simply said a great campaign idea “had legs.” A campaign is a core idea expressed in a series of different executions all advancing a single message. The core idea of a campaign should be flexible enough to allow for executions to work in any number of different media. In terms of copy, the executions all share a tone. In terms of art direction, they share traits such as design and typography.

In The Advertising Concept Book, Pete Barry says, “Each execution should be expressed in the ‘same yet different' way. The executions should be related (the same), but not too closely (different).”18 You want them to all be related but not look like identical twins, or worse, clones. Repetitive executions bore both customers and recruiters.

Be objective.

Once you've put some good ideas on paper and had time to polish them to your satisfaction, maybe it's time to cart them around the hallways a little bit, even before you take them to your creative director. You're not looking for consensus here, just a disaster check.

Doing so can give you a quick reality check, identify holes that need filling, and maybe point to some directions that deserve further exploration. Be objective. Listen to what people have to say about your work. If a couple of people have a problem with something, chances are it's real.

Big ideas transcend strategy.

When you finally come upon a big idea, you may look up from your pad to discover you've wandered off strategy. Well, sometimes that's okay. Good account people understand this happens from time to time. If you've come up with an incredible solution, the account team can help retool the strategy to get the client past this unexpected turn in the road.

My friend Mike Lescarbeau compares an incredible idea to a nuclear bomb and asks, “Does it really have to land precisely on target to work?”

Don't keep runnin' after you catch the bus.

After you've covered the walls with ideas and you've identified a narrative that works, stop. This isn't permission to stop because you're tired or you have a few things which aren't half bad. It's a reminder to keep one eye on the deadline.

Blue-skying is great. You have to do it. But there comes a time (and you'll get better at recognizing it) when you'll have to stop planning and start building this beast. You have a fixed amount of time, so you'll need to devote some of it to making what's good great.

Remember: Always show babies or puppies.

Oh, and one last thing. Always—always—write every headline in the script of a child's handwriting. It's very cute, don't you think? And don't forget to have at least two of the letters be adorably backward. Backward ![]() s are best. Backward Os don't work. Here's a regular O and here's a backward O. See? Not nearly as adorbs as a backward

s are best. Backward Os don't work. Here's a regular O and here's a backward O. See? Not nearly as adorbs as a backward ![]() . (Just checking to see if you're awake.)

. (Just checking to see if you're awake.)

NOTES

- 1. Pete Barry, The Advertising Concept Book (London: Thames & Hudson, 2008), 56.

- 2. Steven Pressfield. The War of Art: Break Through the Blocks and Win Your Inner Creative Battles (New York: Black Irish Entertainment LLC).

- 3. Ian Grais et al. Rethink the Business of Creativity (Vancouver BC: Figure 1 Publishing, 2020), 161.

- 4. Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird (New York: Doubleday, 1994), 23.

- 5. Stefan Mumaw, Chasing the Monster Idea: The Marketer’s Almanac for Predicting Idea Epicness (Avon, MA: Adams Media, 2011), 208.

- 6. George Felton, Advertising Concept and Copy (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1994), 267.

- 7. Teressa Iezzi, The Idea Writers: Copywriting in a New Media and Marketing Era (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

- 8. Mario Pricken, Creative Advertising: Ideas and Techniques from the World’s Best Campaigns (London: Thames & Hudson, 2002), 22.

- 9. Marshall Cook, Freeing Your Creativity: A Writer s Guide (Cincinnati: Writer s Digest Books, 1992), 7.

- 10. David Fowler, The Creative Companion (New York: Ogilvy, 2003), 7.

- 11. W. Glenn Griffin and Deborah Morrison, The Creative Process Illustrated: How Advertising’s Big Ideas Are Born (Cincinnati: How Books, 2010), 81.

- 12. Ralf Langwost, How to Catch the Big Idea: The Strategies of Top Creatives (Erlangen, Germany: Publicis Corporate Publishing, 2005), 188.

- 13. Sandra Karl, Advertising Age (October 14, 1968).

- 14. Phillip Ward Burton and Scott C. Purvis, Which Ad Pulled Best: 50 Case Histories on How to Write and Design Ads That Work (Lincolnwood, IL: NTC Business Books, 1996), 26.

- 15. Jim Aitchison, Cutting Edge Advertising (Singapore: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2004), 186.

- 16. Laurence Minsky, How to Succeed in Advertising When All You Have Is Talent (Chicago: The Copy Workshop, 2007), 313.

- 17. Ian Grais et al. Rethink the Business of Creativity, 165.

- 18. Pete Barry, The Advertising Concept Book, 96.

- * The PORSCHE CREST, PORSCHE, and BOXSTER are registered trademarks and the distinctive shapes of PORSCHE automobiles are trade dress of Dr. Ing. H.c.F. Porsche AG. Used with permission of Porsche Cars North America Inc. Copyrighted by Porsche Cars North America, Inc. Photographer: George Fischer.