8

REWIRING YOUR BRAIN: CHASING IDEAS AND MAKING BIG CREATIVE LEAPS.

MUCH OF THE DAY-TO-DAY LIFE of working in an agency is spent putting out fires. These fires are usually lit by the client and can happen for any number of reasons.

The fire drill could be caused by a change in the client's business situation, such as a competitor coming out with a new model. The alarms might go off because of stock market fluctuations, weather, or, as we've seen, a global virus. Whatever starts the fire, you can be sure phones are gonna ring at the agency and sooner or later you'll find yourself in a meeting with a problem to solve.

Problem-solving is de rigueur at an agency. Even when an account is running smoothly, problems crop up like weeds: uh-oh, supply-line issues just changed your client's available inventory. The licensing on some music ran out and you have to recut a video to a new track. And the old reliable: client changed mind, hates campaign.

The thing is, problem-solving isn't where today's most interesting work happens. Problem-solving issues are usually ones of maintenance. But when big breakthrough ideas happen in advertising, when ideas come along that are big enough to enter the national conversation, it's rarely because somebody solved a problem.

The best stuff often comes from problem-finding.

Why solve problems when finding problems is way cooler?

Think of problem-finding as creative research and development. Basically, problem-finding is a playful screwing around and what-iffing that can result in giant leaps forward, leaps nobody was expecting because the problem didn't exist until you pointed it out.

Problem-finding starts with a long hard look at a client's business. The team at the agency takes a step back, shakes the Etch-A-Sketch, and challenges their own assumptions. They study the client's customers, stores, data, and systems. They look for bottlenecks, redundancies, unmet customer needs. Once they've found an interesting problem, usually one the client didn't know they had, it becomes a matter of problem-solving again.

You'll likely never get a creative brief for problem-finding. If they're honest, most agency leaders will admit their biggest creative success stories didn't come from a creative brief anyway. Which isn't surprising. How do you place an order for something that doesn't exist yet? When you think about it, there was no job order for the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. No creative brief for Apple's iPhone. Jobs himself said, “People don't know what they want until you show it to them.” Clients are no different and may not know what they want until an agency shows it to them.

This notion of creative research and development isn't a new one. It was popularized most recently by a corporate policy Google published during their initial IPO. Called “20 percent time,” it enabled all Google engineers to devote at least 20 percent of their time to working on projects that had no promise of paying immediate dividends, but might bring big returns later. And although 20 percent time is no longer the established policy at Google, pretty much every business guru on the planet came out of the water to agree it's the kind of initiative that can push any business forward.

Unfortunately, agencies are like most other businesses and hire only enough staff to service current business needs. Consequently, creatives rarely have the hours in their schedule to think deeply on clients' bigger issues or to pursue any problem-finding. It's all problem-solving, 24/7.

In Chapters 3 and 4, we discussed the key issues of figuring out what to say and how to say it; as well we should, because authentic strategy and messaging are important. But if we take a quick look back at the advice given in those two chapters, we can arguably frame much of it as problem-solving. We were wrestling with the problem of “How do we say or show our key message in a creative enough way to be noticed and remembered?”

But the word messaging presupposes the solution to a given client problem is messaging. It could be. However, with more and more people watching and reading stuff from commercial-free platforms, the old media buys of print-TV-outdoor-and-radio may not get us the attention we need. On top of that, if the only two dials on our dashboard that we can fiddle with are MESSAGE and MEDIA, we're limiting our ability to explore new territory and perhaps make some giant creative leaps.

One way we can make a leap is to question the brief.

How might we?

Problem-finding requires a different approach than problem-solving.

One of the first tenets of problem-finding is to question the very question we're asking and to perhaps toss it overboard. This sometimes requires us to reverse engineer our creative brief, to peel past the deliverables being asked for so we can explore the core business problem the brief was intended to help solve in the first place. Deconstructing the brief requires an open-mindedness often referred to as “beginner's mind.”

The total beginner often asks questions about things people “already know” and take for granted. They ask the obvious questions people too close to the problem can look past. The question's very naiveté often leads to answers that've been overlooked. Where we might usually settle for responses like, “That's just the way things are,” beginner's mind pushes forward and wonders, “Well, why are things the way they are?”

In an interview, W+K's Dan Wieden said, “When you begin a piece of work, it's essential you somehow rinse your brain of everything you think you know about that project, or the subject, and somehow realize how ignorant you are—and how stuffed you are—with preconceptions about things. You need to get rid of all that and approach it new.”1

Researcher Min Basadur developed a popular process for innovation with some similarities to beginner's mind. His process, now marketed as the Simplex Process, is based in part on these three words: “How might we … ?” Tim Brown, CEO of Ideo, explains why the HMW approach is so effective:

- HOW assumes solutions actually do exist and provides the creative confidence needed to identify and solve for unmet needs.

- MIGHT gives us permission to play with ideas that might or might not work—either way, we learn something useful.

- WE signals that we're going to collaborate and build on each other's ideas to find creative solutions together.

With HMW in mind, let's pretend we have a creative brief telling us to convince Apple iPhone owners to switch to the new 5G-ready Samsung phone, because it has a new and better camera.

Well, we could choose to jump right in and start coming up with campaigns that show off the Samsung's great camera features. But such a features-driven campaign is based on—and perhaps limited by—the question inherent in the brief, namely, “Why buy an iPhone upgrade when the Samsung's camera is so much better?” Basadur's HMW process suggests we can try other ways of framing the question. Among many other possibilities, we might try these:

- Why stay in Apple's operating system when Samsung's Android can improve the whole phone experience, including photography?

- Why buy an SLR 35-millimeter camera when you can get similar features of flexibility and control with the camera on the new Samsung phone?

- Why buy any phone for a camera upgrade? Samsung's 5G-readiness sets you up to take advantage of every leap forward in software and connectivity.*

Maybe one of these alternate routes might take us to a more effective campaign for Samsung; maybe not. But consider how far we've moved from trying to say something clever about Samsung's phone-camera for a poster in the window at the Verizon store.

HMW thinking could lead to some interesting deliverables beyond the cookie-cutter media usually listed on creative briefs. Such as: What if we got a Hollywood director to shoot their next big movie on a Samsung and then advertise the movie? What if we set up an arcade of Samsung phones at e3, the big video game convention; and as gamers reacted to their improved game play because of 5G's massive bandwidth, photographers could capture great images and let gamers post them on their social media.

Are these great? I just thought ’em up now, so probably not. But could they have come from the brief as it was written? Definitely not.

Innovation expert from MIT, Hal Gregersen, has a different term for a concentrated round of HMW thinking: “When people in a group are struggling with an issue and find they're getting nowhere … that's the perfect point to back up and do some question-storming.”2

In his wonderful book, A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas, Warren Berger takes readers through similar scenarios that illustrate how finding the right questions can lead to creative leaps forward.

As a junior, it's not likely you'll be asked to do any how-might-we thinking your first week on the job. But there is a time to do it—after you've finished doing what's asked for in the creative brief. Once you solved the problem as it's presented, then it's time to turn on the afterburners and overdeliver with some problem-finding.

Tom Monahan's wonderful exercise: Ask a better question.

In his great book The Do-It-Yourself Lobotomy, Tom Monahan has another method that can lead to big ideas. He calls it “Ask a Better Question” and I'm lifting it in its entirety here (with Tom's permission) because I've seen students use it to get to brilliant campaigns again and again. I've also seen Tom explain it in a workshop.

So, there's Tom, up at the front of the room, wearing a dark sport coat, dress shirt, black jeans, and black shoes. And he asks the room, “What am I wearing?” Well, that's easy, we think. And people in the room say pretty much what I just said: dark sport coat, dress shirt, black jeans, and shoes.

But then he asks, “What kind of socks am I wearing?”

People lean into the aisles and try to get a look at his socks, but his jeans come down to his shoes, so there's no way to know. But he doesn't accept “don't know” as an answer. “What kind of socks am I wearing?”

And the room starts tossing out ideas: Black socks. White. Tan. Striped. Gold Toe. No socks. Then he pushes them further: “What's an unusual design you wouldn't expect me to have on my socks?” The answers take a left turn becoming quirkier: Baseballs. Santa Claus. Fish. And finally, Tom asks, “What is the most unusual out-there design you would never, ever expect to see on my socks?”

And now the ideas start to come in from the moon: Flying elephants. DNA strands riding bicycles. “Bela Legosi in a swimsuit,” said one.

The early answers tend to be pretty lame. And I'll take the blame because I was asking pretty lame questions. I was asking questions that allowed you to stay in the known. Since our childhood years we've always strived to know the answer, and the answer is something that already exists, so we tend to go with what already exists… . [But] the mind is capable of imagining much more than what you know, particularly if you're encouraged to do so. It's just that we tend to put ourselves in a predefined context in terms of solving problems or answering questions. This determines how we approach a situation. We put ourselves in a context that can be addressed with a known, but when asked progressively more probing questions, you had no choice but to push your mind to a place you've never been before. By definition, the question forced you there.3

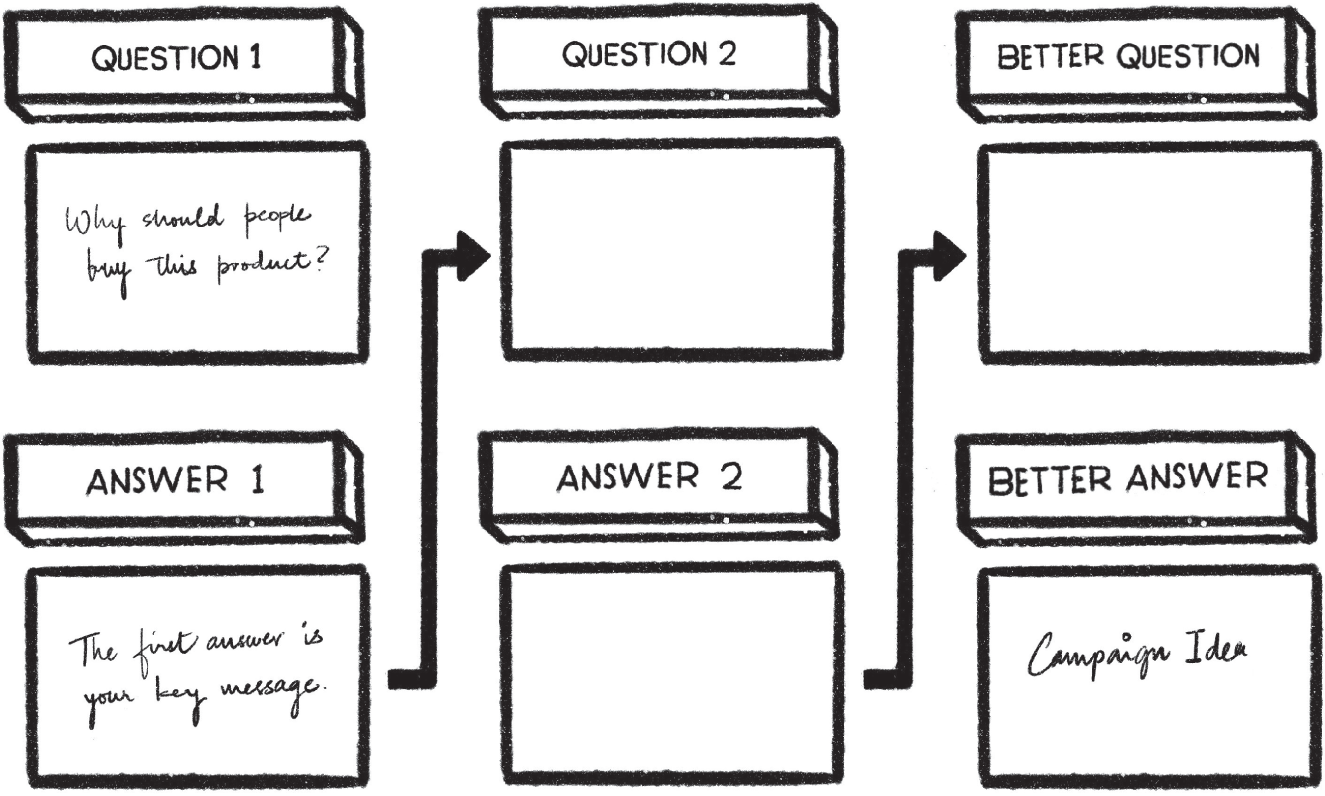

You can use Tom's system of asking progressively more probing questions to get to a big brand idea. In Figure 8.2, you see a worksheet based on Tom's process similar to one I hand out in class. On the sheet it looks as if the questions end after three rounds, but finding the right question can require 30 or 40 rounds or more. However, the three rounds listed there demonstrate the relation of each answer to the previous question.

- QUESTION 1: This is a basic question, relevant to the problem for which there is a correct answer. Because we know the answer, there is no creativity involved.

- QUESTION 2: This is a related question derived from the answer to the previous question, for which we can guess a likely answer. Because we can make only an educated guess, there's some creativity involved.

- QUESTION 3: This is a further related question derived from the answer to the previous question for which there is no correct answer. We cannot know or even guess at an answer. Creativity is required. (Ultimately, this is the final, “better question.”)

To kick it off, I tell students, let your first question always be, “Why should people buy this brand?” And let the first answer be the key message you're working with. Maybe it's something like, “It's the only brand that can FILL IN THE BLANK.”

Figure 8.2 Question 1: “Why should people buy this product?” Answer 1: Your key message. Then challenge every answer with another question.

As an example, one of the student teams was working on Purell anti-bacterial hand sanitizer. So, question 1 was: Why should people buy Purell? Answer 1 was their main message: “Purell kills 99.99999 percent of all bacteria within 30 seconds of contact.”

Working at the whiteboard, we began compiling a long messy list of more probing questions, most of which began with “why”? The trick with working “Ask a Better Question” is being willing to chase down all kinds of crazy questions. Many of these question threads will lead to a blind alley, a sort of dead end you don't know what to do with. At which point, you simply back up, rephrase your last question, and keep going again.

Answer 1 said “it kills 99.99999 of bacteria within 30 seconds.” We could have asked “Why does it take 30 seconds to be effective?” but instead our second question was, “Why do we want to kill bacteria?” It seemed promising at first but ultimately didn't lead us anywhere. So, we backed up and tried, “Why only 99.9999 percent of bacteria?” which after a while led to “What happens to the 0.0001 percent?” which led to “How does that one single bacterium manage to survive?” which led to “Is it always the same bacterium Purell doesn't get?” Which led finally to our first possible campaign about a bacterium, we named Steve or something—turns out he was just a bully and now that his posse's gone, Steve just lives in the toilet. (Very silly, I know.)

We decided to go back and pick up that other thread, the one that started with the second question of “Why does it take 30 seconds to be effective?” We ran up and down a few blind alleys again, but we stayed with the second line of query and arrived finally at a better question: “What goes through a germ's mind in the last 30 seconds of its life?” Clearly, a question that has no answer and requires a creative leap. They turned it into a really fun campaign.

Another team was working on Orkin Pest Control. The usual first question was “Why should people call Orkin and not some other service?” Their answer was the key message: Orkin guarantees to get rid of all the bugs. After some false starts the second question became, “How can Orkin offer a guarantee?” which was answered with “Because if the bugs come back, so does Orkin.” Next question was: “But why don't the bugs come back?” Answer: “Because Orkin gets rid of the bugs you see as well as the ones you don't see.” Question: “What's wrong with the bugs we don't see?” The penultimate answer was “Because the bugs you don't see will make more bugs.” And the final better question was, “Where are cockroaches having sex in your house right now?” (The silverware drawer? The cookie jar?) And that is a campaign-able idea.

In an interview, Dan Wieden mirrored this better-question process: “A good assignment is always a question. The best brief is a well-defined question. Such a question fulfills two important criteria: you don't know the answer to it, and it comes out of the heart of the issue you're dealing with.” With Wieden's statement in mind, look again at the worksheet in Figure 8.2, but read it backwards. You'll see the progression ends on a question we don't know the answer to, but started with the key message plainly stated in the first answer “Orkin guarantees to get rid of all the bugs”—the heart of the issue we're dealing with.

And it all starts with “Why?”

In Hegarty on Advertising, BBH's John Hegarty wrote: “The most important word a creative person can use is ‘why'? The word ‘why' not only demands that we constantly challenge everything, but it also helps the creative process. It's like that wonderful thing children do, they constantly ask: Why? Why is it like that? Why do we do that? Why can't I go there? Why? Why? Why?”

This ruthless interrogation of the core issue, this jackhammering of the brief, is why I've decided my name for Monahan's process is the Toddler Socratic Method. My little rug rats drove me crazy sometimes because they never stopped asking, “Why? Why? Why?”

Try rewriting the brief's key message as a key question.

As we've noted, part of the issue here is the word message, which suggests a message will solve the client's problem. But more troubling is how we creatives often interpret this message. We see this line item on the creative brief not so much as a message, but as the actual solution to the client's business problem.

I remember I sometimes walked out of briefings thinking, “So, if I can just say this message creatively, I'll have solved the problem.” This assessment, however, assumed the solution was a message. This isn't surprising when you consider the brief hands you a message as if it were the solution. But is being handed a solution really the best way to search for a breakthrough idea?

So instead of a key message, what if we could boil all our research and thinking down to a key question? A question we then answer with our solution and the solution is the creative idea.

When you think about it, having an intriguing question to answer is much more inspiring than being handed a message to impart. A question has more spring to it, more potential energy, because it's unfinished. A key message doesn't ask anything of us creatively. It's fully cooked. But a key question is like a riddle that produces an itch and the creative soul will want to scratch it—with ideas. A well-defined question goads us, pushes us. It's like that famous statement, “A powerful question never sleeps.”4

Formulating this key question first requires us to make the main business problem “as clear and naked as possible,” in ad veteran Bob Moore's words. What exactly is the key business issue at hand? What exactly is stopping what we want to happen … from happening? How can we take everything we know—about the brand, its customers, its competition—and reduce the whole problem down to one challenging question?

Recalling GS+P's famous got milk? campaign, strategist John Steele's brief didn't have a key message like “Milk builds strong bones.” He reformulated his main research finding—milk is almost a required pairing with many foods—as a question and handed it to the creative teams: “What happens if there's no milk?”

It's at this moment, when the strategist hands the right question to the creatives, the “why?” can turn into a “what if?” The final question, which has no correct answer, puts the creative team in a place where they have no choice but to just … wonder. A state of wonder. Which is a fine way to describe creativity.

Monahan's Intergalactic Thinking.

A NASA scientist named David Murray described a technique in A More Beautiful Question he likened to “borrowing ideas from faraway places.” He noted “the most creative ideas result from ‘long-distance' connections, bringing together ideas that seem unrelated and far apart… . The most promising connective inquiries,” he said, “do not merely ask, What if we combine A and B, but What if we combine A and Z? (Or better yet, A and 26?)”5

In “Intergalactic Thinking,” Monahan calls those faraway places galaxies, and it's another marvelous ideation technique from his book I've seen students use with great success.

Think of a galaxy as everything you know about a given subject. The universe of your brain is full of galaxies: there's a sports galaxy, a music galaxy, one for cars, movies, you name it. Like real galaxies, every subject galaxy in our heads contain millions of points—kind of like stars—but here they're data points, facts we know about a particular subject.

To try Intergalactic Thinking, we start by first populating our home galaxy on a page in our notebook. If we're working on, say, Orkin Pest Control service, under our subject galaxy heading of ORKIN, we list 40 or 50 facts and data points about this brand and category. We might populate this galaxy with words such as roaches, bugs, house, guarantee, gestation, skittering, larva, infestation, crunch, and eewwww!

Then we build other galaxies based on subjects as far from bugs as we can make them. Here's how Tom describes it:

Simply think of a galaxy of thought outside your everyday realm. I usually suggest people choose a galaxy that's fairly familiar, one very unrelated to their line of work, and one with many, many data points. I love using galaxies such as “the farm,” “the ocean,” or “the circus.” I don't like galaxies with relatively few data points—like backgammon, taxidermy, or Russian musical instruments. Start by picking a few data points in the galaxy of choice. If it's the ocean, you might choose “sand,” “starfish,” “boats,” and “wind.” Then, just try to connect these seemingly unconnected concepts to the problem at hand.6

Just screwing around here as I write, I took Tom's advice and created a CIRCUS/FAIR galaxy and toggling back and forth between this new galaxy and my original ORKIN galaxy, I came up with these:

- Six-legged clowns in a freak show

- Nighttime circus tented under your bedsheet

- Roaches arriving in small clown car

- Bug jugglers

- Roach Tunnel of Love (Eeewwww.)

None of these really work, but I do like how far I am already from boring ideas like “The Orkin Man.” The trick is to force ourselves to look for ideas far outside of the well-trod areas we're familiar with.

Monahan says when we can't find a solution working in the familiar territory of a known world, we're forced to create solutions by exploring a new galaxy.

Getting to big ideas by creating hashtags.

This next process is very much like Monahan's Intergalactic Thinking with a small difference. But let's start by talking about that brilliant Coke Zero campaign discussed in Chapter 7. You remember, the one where the platform was “Coca-Cola sues Coke Zero for tasting too much like Coca-Cola.”

Okay, that was the idea. But the hashtag Crispin pulled out of the idea was #TasteInfringement.

Those two words, all by themselves, sum up the whole idea. That strange pairing made the whole platform instantly understandable. On top of that, the pairing made it searchable, which is why hashtags were originally created.* But for our purposes here, they can also help us search for ideas.

It goes like this. Instead of pulling the hashtag out of an existing idea, what if we created the hashtag first and then pulled a campaign out of the hashtag? Think of it this way. If your main idea is a book, the hashtag is kind of like the title, right? So, what if we came up with the title first and then wrote the book?

Here's where this process resembles Monahan's Intergalactic Thinking. But now, instead of choosing a distant galaxy, we'll use galaxies from subjects very close to the problem we're working on. And we can get categories for these close-by galaxies by looking at the truths of our product, its category, or the customer.

Let's say we're trying to come up with a campaign idea for Orkin again, but this time we're going at it backwards by creating a hashtag first.

We might mix things from our home galaxy ORKIN with things in the nearby galaxy of HOMES. It's nearby, obviously, because Orkin rids homes of pests. We'd fill that galaxy with as many key words as we could such as castle, welcome mats, occupants, and so on. But we could just as easily make a galaxy out of WAR or DEATH. Death seems promising and on my first try I get a pairing of “roach ghost,” and now I'm wondering what words are in a roach prayer. Or if roach religions have a St. Peter Roach at some teeny-ass Pearly Gates.

Figure 8.3 You don't have to create galaxies like I've done here. Just scribbling two lists in a notebook is fine. After a while, you'll be able to do this in your head.

Low-hanging fruit? Probably, but my focus here is to show how this process works. Now let's look at a fully worked-out example where the team landed on a wonderful hashtag and then turned it into a campaign.

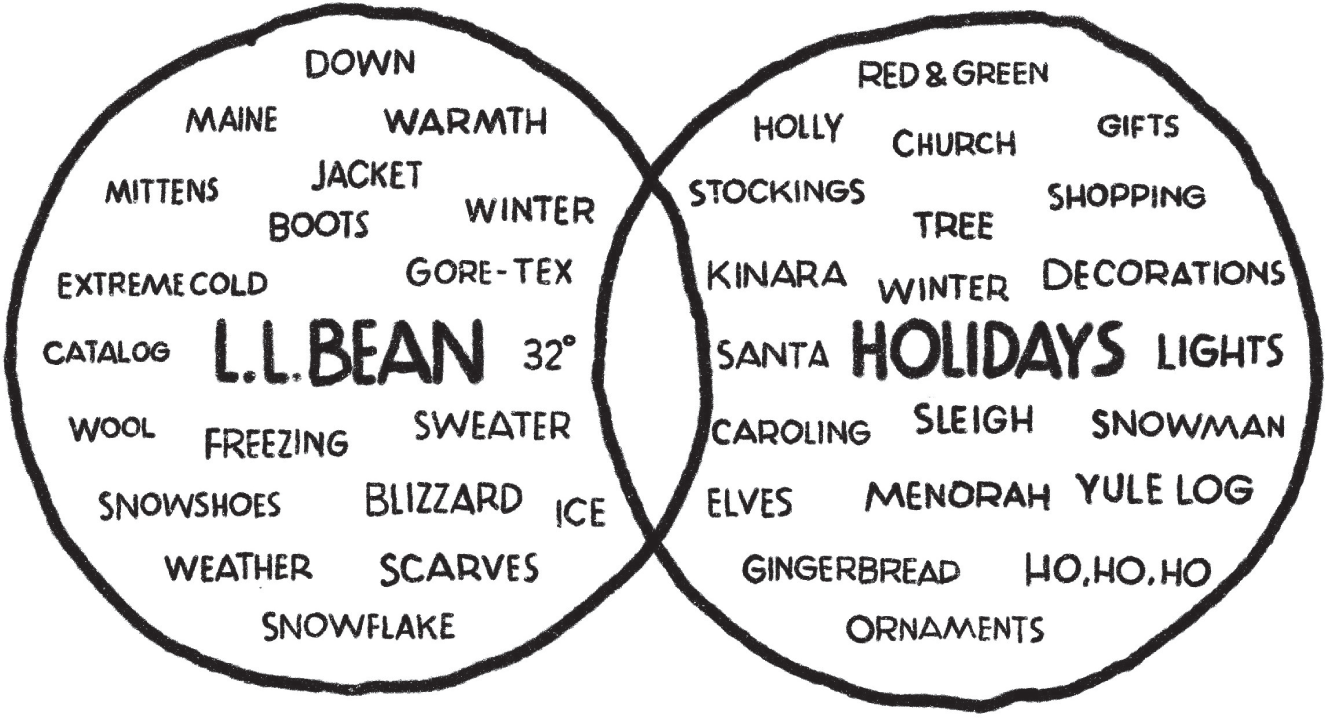

This one happened when my friends, Wes Whitener and Mitch Bennet (then at GSD&M), were tasked with creating a campaign for L.L.Bean's annual holidays sale on winterwear. Mitch and Wes didn't draw circles like you see in Figure 8.3, but on their sketch pads and in their heads, the process was exactly the same.

First, they had the L.L.Bean galaxy. As you can see, one is filled with things that come directly out of the L.L.Bean galaxy: Maine, ice, jacket, extreme cold, Gore-Tex, boots, wool, and so on.

For the other galaxy, they could have created ANTARCTICA or maybe SURVIVAL. They could have created a CLICHÉD SALES WORDS galaxy and filled it with all the things car salespeople do: savings bonanzas, balloons, clowns, blow-outs and “BLANK-a-thons.” But instead, they just noodled around with the HOLIDAYS galaxy, populating it with things like Christmas tree, stockings, lights, kinara, carolers, sleighs, elves, whatever.

Then they just let their eyes play over the two galaxies waiting for something to jump out at them. It's the randomness of this technique that can lead to such surprising pairings. As they noodled on their sketch pads, two words serendipitously collided in their heads to form “Extreme Caroling.” And that was the whole holidays winterwear sale.

Remember how we discussed brand platforms in Chapter 7? How you should be able to fit a big idea in a sticky note, and how it should start talking, revealing its possibilities? Well, this fit in a note and when it started talking, the first thing it said was a TV commercial.

The spot opens on a mountain climber waiting out a blizzard in one of those tents bolted to a cliff's sheer surface. Suddenly, two other climbers rappel down into frame (dressed snuggly in their L.L.Bean winterwear) and begin singing “Deck the Halls” to the surprised tent dweller. The blizzard rages on, the singing continues, as type appears on the screen, with names and prices of the winterwear, and it all ends with “Happy Holidays from L.L.Bean's Extreme Carolers.”

It's very Happy Holidays, very L.L.Bean, and it can be stretched into many different executions.*

Note that there's no need to do a Venn diagram as I've done here—Mitch and Wes just noodled with words on their notepad. Note also that not every campaign needs a clever two-word hashtag, but big campaign ideas often have them. Thomas Kemeny touched on this in Junior. He said coming up with a name for an idea can be as important as the idea:

It's the shorthand everyone will use both internally and externally to pitch the idea. It's the name the client will say in the lunchroom to impress their coworkers. It's also the way the press will introduce it to the world and will likely be your hashtag. One good way to come up with a name is to think of it as a one or two-word headline. Look into the brand's DNA and the experience idea itself and think of words that overlap between the two. Make the name telegraphic and clear as to what the idea is. If there's no perfect word, consider making one up, or mashing up two words.7

See for yourself. Search for these two mash-up words on YouTube: hungerithm and flybabies.

NOTES

- 1. Ralf Langwost, How to Catch the Big Idea: The Strategies of Top Creatives (Erlangen, Germany: Publicis Corporate Publishing, 2005), 155.

- 2. Warren Berger, A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 153.

- 3. Tom Monahan, The Do-It-Yourself Lobotomy (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons 2002), 80.

- 4. Attributed to Professor David Cooperrider of Case Western Reserve University.

- 5. Warren Berger, A More Beautiful Question, 105.

- 6. Tom Monahan, The Do-It-Yourself Lobotomy, 118.

- 7. Thomas Kemeny, Junior: Writing Your Way Ahead in Advertising (Brooklyn: Powerhouse Books, 2019), 116.

- * I'm not an expert in technology and these questions may in fact be technically naïve. If so, please email your complaints to biteme.com.

- * An early Twitter user, Chris Messina, thought finding specific conversations in the endless scroll of tweets was too difficult. He pitched the # idea to Twitter in 2008, but they dismissed it. But the search tool caught on by itself. Twitter added it in 2009, and it eventually it spread to all social media.

- * For the record, this campaign was presented and, within two minutes, the client killed it. Why? I don't remember. Welcome to advertising.