16

PECKED TO DEATH BY DUCKS: PRESENTING AND PROTECTING YOUR WORK.

ABOUT 20 PERCENT OF YOUR TIME IN the advertising business will be spent thinking up ideas. Eighty percent will be spent protecting them. And 30 percent doing them over.

A screenwriter was looking out onto the parking lot in front of Universal Studios one day. It occurred to him, said this article, that every one of those cars was parked there by somebody who came to stop him from doing his movie.

The similarity to advertising is chilling. The elevator cables in your client's building will fairly groan hauling up all the people intent on killing your best stuff.

When word gets around the client's offices that the agency is here to present, vice presidents and assistant vice presidents will appear out of the walls and storm the conference room like zombies in Night of the Living Dead, pounding on the door, hungry arms reaching in for the layouts, pleading, “Must kill. Must kill.”

I have been in meetings where, after the last idea was presented, an eager young hatchet man raised his hand and asked his boss, “Can I be the first to say why I don't like it?”

I have been in meetings surrounded by so many vice presidents, I actually heard Custer whisper to me from the grave, “Man, I thought I had it bad. You guys are, like, so dead.”

You will see ideas killed in ways you didn't know things could be killed. You will see them eviscerated by blowhards bearing charts. You will see them garroted by quiet little men bearing agendas. A comment from a passing janitor will pick off ads like cans from fence posts and casual remarks by the chairman's spouse will mow down whole campaigns like the first charge at Gallipoli.

Then there's the “friendly fire” to worry about. A stray memo from your agency's research department can send your campaign up in flames. Your campaign can also be fragged by the ill-timed hallway remark of an angry coworker.

War widows received their telegrams from ashen-faced military chaplains. You, however, will look up from your desk to see an account executive, smiling.

“The client has some issues and concerns about your ideas.”

This is how account executives announce the death of your labors: “issues and concerns.”

To understand the portent of this phrase, picture the men lying on the floor of that Chicago garage on St. Valentine's Day. Al Capone had issues and concerns with these men.

I've had account executives beat around the bush for 15 minutes before they could tell me the bad news. “Well, we had a good meeting.”

“Yes,” you say, “but are the ideas dead?”

“We learned a lot.”

“But are they dead?”

“Well, … your campaign, it's … it's with Jesus now.”

What follows are some quixotic arguments that may help protect your loved ones in future battles. If you find any of them useful, I recommend you commit them to memory. It's my experience what a client decides in a meeting stays decided.

PRESENTING THE WORK.

Learn the client's corporate culture.

Spend some serious time with the client. Talk to the quiet guy from R&D. Tell jokes with the product managers. The more they know you, the more they're going to trust you. The more they trust you, the more likely they are to buy these strange things you call ideas.

But you're going to learn something about them, too. You're going to get a feel for the tone of this company. How far they're willing to go. What they think is funny. You'll save yourself a lot of grief once you understand this. Remember, they see you as their brand ambassador. They're trusting you to accurately translate their corporate culture to the customer.

This doesn't mean doing the safe thing. It means if your client is church, you probably shouldn't open your TV spot with that scene from The Exorcist where Linda Blair blow-chucks pea soup on the priest.

In a text that came with the Masterclass from Goodby Silverstein & Partners, Rich and Jeff put it this way:

Read the room before, during, and after the pitch. Sometimes pitches are won or lost based on nothing other than likability—aka, whether the client likes you. It's your job to be as likable as possible so your idea has the best chance of survival. This doesn't mean you have to sacrifice your own authenticity in favor of contrived conversation and presentation, but it does mean you need to be sensitive to the client's habits and behaviors. How you dress for a meeting in Chicago might look very different from how you dress for one in Los Angeles, and the more you understand the subtle culture of the company you're pitching, and the city it calls home, the better chance you'll have at forming a sincere relationship with the company and, ultimately, win the job.1

Present your own work.

Nobody knows it better than you. Nobody has more invested in it than you. And if you screw up, you have nobody to blame but yourself.

Two addenda: (1) If you are a truly awful presenter, don't. At least not the big campaigns. Better to have a skilled creative director or account person sell them. (2) Learn to present. It's a skill, and like any other skill, the more you do it the better you'll get. Start small. Sell a small campaign. Present to the account folks. Just do it.

Creatives who can present work well go a lot further and make more money in this business than those who cannot. Not being able to present your own work (or the work of other people) will handicap you throughout your entire career. Pilots can't be afraid of heights. It just doesn't work.

Practice selling your campaign before you go in to present.

Don't just wing it. I used to think winging it was cool. But that was just bravado. As if my ideas were so good they didn't need no stinkin' presentation. Wrong. Sit down with a team member and practice.

Don't try to memorize a speech.

Trying to memorize written material will make you nervous. You'll worry you're going to forget something and you probably will.

Write out a speech if it helps you organize your thoughts but toss it when you're done. What you do need to do is establish what marks you need to hit along the way, and then make sure you hit them. (“I need to make Points A, B, and C.”) Once you see the light go on in a client's eyes regarding A, move on to B.

Don't be slick. Clients hate slick.

You know all those unfair stereotyped images we sometimes have about clients? Uptight, overly rational, number-crunchers? They've got a similar set of incorrect images about us: slick, unctuous, glad-handing, promise-them-anything sycophants. Is it fair? No, but that's the thing about stereotypes. You're a little behind before you even start. So why feed the stereotype trying to be all slick and cool?

But if you're not all slick and buttoned-up, what should you be?

Be yourself. Be smart. Be crisp, be to the point, be agreeable. Don't be something you aren't. It never works. You will appear disingenuous, and so will your ideas.

Keep your “pre-ramble” to an absolute minimum. Dive right in.

That doesn't mean start cold. It's likely you'll have to do some amount of setup. But make it crisp, to the point, and fast.

In a book on the art of good presentations, I Can See You Naked, author Ron Hoff said the first 90 seconds of any presentation are crucial. “Plunge into your subject. Let there be no doubt the subject has been engaged.”2

In those first 90 seconds, the client is unconsciously sizing you up, making initial impressions, and probably deciding prematurely whether they're going to like what you have to say. So don't wade into the water. Dive.

Talk slowly.

I'm stealing the whole next paragraph from my friend Thomas Kemeny's wonderful book, Junior: Writing Your Way Ahead in Advertising.

It's nice you're excited about the work you're presenting. But if you start talking a mile a minute, you might come off as panicked and insecure. Take your time. No need to rush it. Let your client appreciate the work you've put so much time into. Let them hear every word so they understand you. Be loving about it. Treat your work with tenderness and familiarity, even if you just wrote it an hour ago.3

Don't hand out materials before you present.

Stay in command of the room. The minute you hand out a document to an audience, you're competing with the document. Clients are human and will read whatever it is you've just handed them. So don't hand out anything until you've finished presenting. Remain the focus of the room's attention.

Don't present your campaign as “risk-taking work.”

Most clients hate that descriptor. In the agency hallways, it's fine to talk about work being risk-taking. But it's just about the worst thing you can say to clients. They don't want risk. They want certainty. Whether certainty is possible in this business remains in doubt, but clients definitely do not need to hear the R word.

Find other ways to describe your campaign. For instance, “It goes against the grain,” or “It's interesting; it's memorable.” Anything is more palatable than risk to a client with a job on the line, a mortgage to pay, and two kids to put through rehab.

Okay, before we go on to the next paragraph, I just want to say that it's really good. I worked on it a long time and it may in fact be the best paragraph of the whole book. I think you're going to love it.

Seriously. Reeeally good stuff.

Before you unveil your stuff, don't assure the client “you're going to love this.”

This is known as leading with your chin. Somebody's gonna take a swipe at it just to keep you humble.

As they say in law school, don't ask a question you don't know the answer to. Same thing in presentations. Anticipate every objection you can and have a persuasive answer in the chamber, locked and loaded.

Never show a client work you don't want them to buy.

I guarantee you; second-rate work is what clients will gravitate to.

I've allowed myself to present so-so ads and my reasoning went like this: “Well, we gotta sell something to get this campaign going, and time is running out. So, we'll present these five ideas, but we'll make sure they buy only these three great ones. The two so-so ones we'll include just to, you know, help us put on a good presentation. They'll be filler.”

But what happens is, the client will approve the work they feel safer with, less scared by, and that is always the second-rate work.

Conversely, don't leave your best work on the agency floor.

“Oh, the client will never buy this.” How do you know? The clients may surprise you. Maybe not. But don't do the work for them. Hall of Fame copywriter Tom McElligott once told me, “Go as far as you can. Let the client bring you back.”

At the presentation, don't just sit there.

No matter how right your campaign may feel to you, it's not going to magically fly through the client approval process. Even if the client appears to buy it outright, sooner or later someone will start taking potshots. “Little changes” here and there, here and there.

You need to learn to be an articulate defender of your own work. Don't count on the account person to do it. Don't leave it to your partner. Pay attention in the meeting. Try to understand exactly what might be bothering your client. And then come back with the most articulate defense you can.

As you form a defense, your first instincts may be to build a bridge from where you are to where your client is. (“If only I could get them to see how great these ads are.”) Instead, get over to where your client is and build a bridge back to your position. With such an attitude, your argument will be more empathetic and more persuasive, because you're seeing the problem from your client's perspective first.

“They may be right.”

According to ad legend, Bill Bernbach always carried a little note in his jacket pocket. A note he referred to whenever he was having a disagreement with a client. In small words, the note read, “They may be right.”

Here's my advice, and it starts a few rungs further down the humility ladder: always enter into any discussion (with clients, account executives, anybody) with the belief there is a 50 percent chance you are dead wrong. I mean, really believe in your heart you could be wrong.

I think such a belief adds a strong underpinning of persuasiveness to your argument. To listeners, it doesn't feel like you're forcing your opinion on them.

I often think it's analogous to the two kinds of ministers I've seen. The quiet and anonymous minister at a small church who invites me to explore his faith. And the noisy kind I see on TV, sweaty and red-faced, telling me the skin's going to bubble off my soul in hell if I don't repent now.

Which one is more persuasive to you?

Listening doesn't mean saying “yes.”

Listen, even when you don't want to. It doesn't cost you anything to listen. It's polite. And even if you think you disagree, by listening you may gather information you can later use to put together a more persuasive argument. (As they say, “Diplomacy is the art of saying ‘nice doggie' long enough to find a big rock.”)

I think our culture portrays passive postures (such as listening) as losing postures. But I think listening can help you kick butt. Relax. Breathe from your stomach. Listen.

Choose your battles carefully.

No matter how carefully you prepare your work, no matter how impeccable you are about covering every base, crossing every t, dotting every i, the client's red pencil is gonna come out. Someone is going to mess with your visual and change your copy.

H. G. Wells wrote, “No passion in the world is equal to the passion to alter someone's draft.”

We need to pause here for a minute so I can make this point as clear to you as I am able. It's an important one.

Millions of years of evolution have wired a network of biological certainties into the human organism. There is the need to eat. There is the need to sleep. And then, right before the need to procreate, is the client need to change every idea the agency presents. This need is spinal. Nothing you can do or say, no facts you lay down, no prayers you send up, will stop a client from diddling with your concept. It's something you need to accept as reality as early in your career as you can.

It didn't start with you, and it'll still be going on the day some Detroit agency presents its campaign for the new antigravity cars. The fact is, we're in a subjective industry—partly business and partly art. Everybody is going to have an opinion. But the clients have paid for the right to have their opinion. Advertising, ultimately, is a service industry.

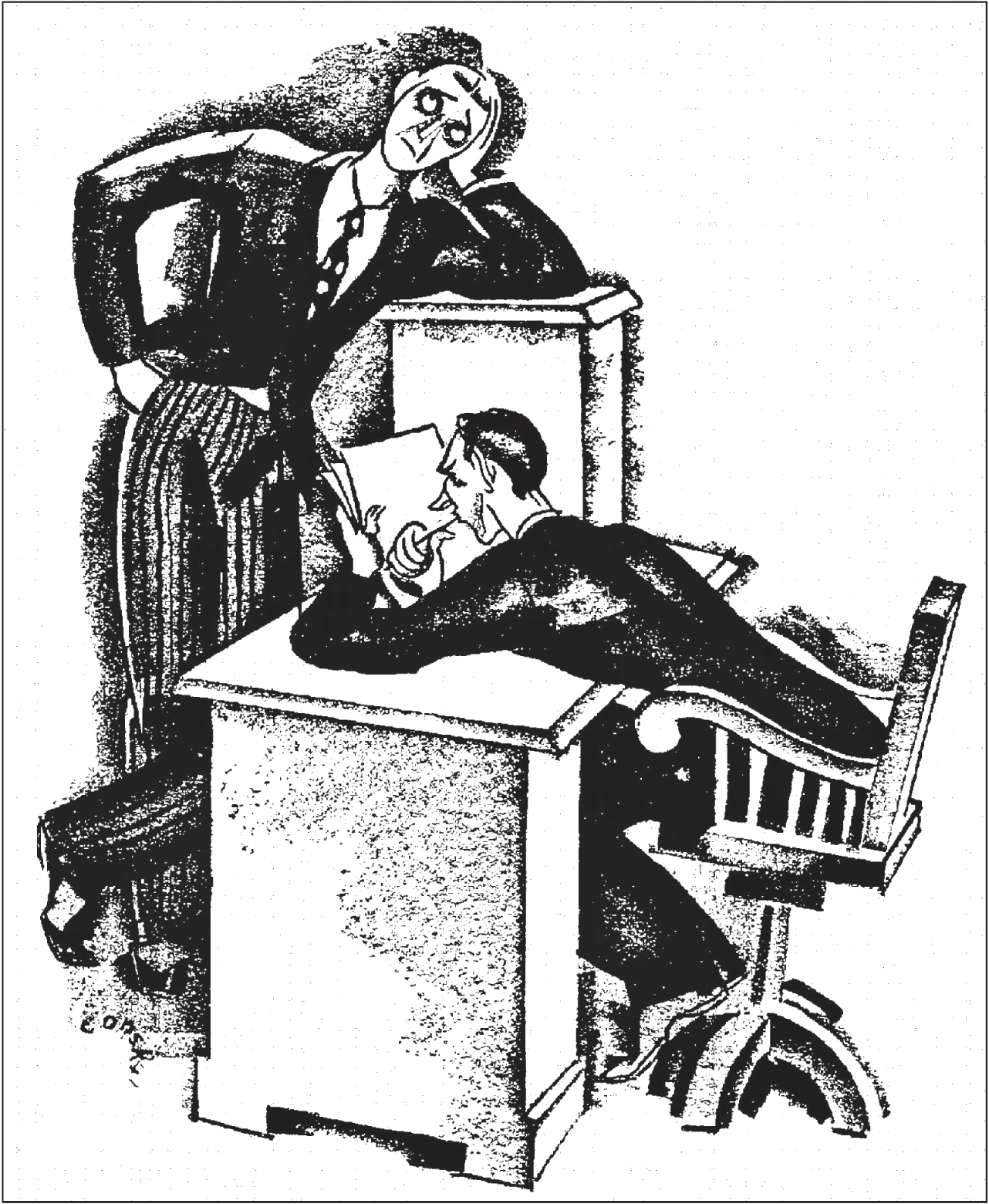

Consider the drawing reprinted in Figure 16.2 of a client making changes to an ad as a frustrated copywriter looks on. I found this image in a book called Confessions of a Copywriter, which was published in 1930. That date again—1930.

Figure 16.2 Except for the clothes, this 1930 engraving of a client changing a writer's copy looks like it could have happened yesterday.

© Reprinted with permission of Dartnell Corporation.

They were doing it then, and I suspect they've been doing it since earliest recorded history. I have this image of a client in Egypt, looking at some hieroglyphs on the walls of the pyramids, saying, “I think instead of ![]() we should say,

we should say, ![]() .

.

Get used to it. Even some of the writing on this page about rewriting was rewritten by my publisher's editor. Nothing is safe.

I say, if they want to mess around with your body copy, let them. If they want to change the colors from red to green, let them. Any hieroglyphs they want to change, let ’em. Protect the pyramid. If you get out of there with the big idea intact, consider yourself a genius.

Tom Monahan says, “Squabbling over body copy and other details is not where the advertising battles are won. Ideas—big, differentiating, selling ideas—are what win. And anything that takes away even an ounce of energy from the creating or selling of those ideas is misdirected effort.”4

The moral: don't win battles and lose the war.

CREATIVE TESTING: BE AFRAID. BE VERY AFRAID.

In advertising, research isn't science.

Here's how advertising works: you toil for weeks to come up with a perfect solution to your client's business problem. Then your campaign is taken to an anonymous building on the outskirts of town and shown to a focus group—people who've been stopped in the mall the previous week, identified as target customers, and paid a small amount of money for their opinion.

After a long day working at their jobs, these tired pedestrians arrive at the research facility and are led into a small room without windows or hope. In this barren, forlorn little box, they are shown your work in its embryonic, half-formed state while you and the client watch through a one-way mirror.

Here's the amazing part. These people all turn out to be advertising experts with piercing insights on why every idea shown to them should be jammed into the nearest shredder fast enough to choke the chopping blades.

Yet, who can blame them? They've been watching TV since they were kids and have been bored by a hundred thousand hours of very, very bad commercials. Now it's payback time, Mr. Madison Avenue Goatee Man. And because they're seeing mere storyboards they think, wow, we get to kill the beast and crush its eggs.

Meanwhile, in the room behind the mirror, the client turns to you and says, “Well, looks like you're workin' the weekend.”

Welcome to advertising.

A committee, it has been said, is a cul-de-sac down which ideas are lured and quietly strangled. The same can be said for the committee's cousin, the focus group. But this research process, however wildly capricious and unscientific, is here to stay.

Clients are used to testing creative. They test their products. They test locations for their stores. They test the new flavor, the packaging, and the name on the top. And much of this kind of testing pays off. So don't think they're going to spend a couple million dollars airing a commercial based solely on your sage advice: “Hey, business dudes, I think this idea rocks.”

Used correctly, research can be very useful. What better way is there to get inside the customer's head and find out what people like and don't like, to understand how they live? The thing is, the good research isn't done in those beige suburban buildings, but downtown in the bars, asking drinkers about their favorite booze. Or at the malls, asking shoppers why they chose a certain product, or eavesdropping on real people anywhere as they talk about a category or a brand.

Of course, there's another place you can hear all this conversation. This marvelous place has reams of up-to-the-minute, real-time research and customer verbatims and it's all free. In Pete Barry's The Advertising Concept Book, Mike Troiano of Holland Mark Digital reveals a secret: “Introduce your clients to better, faster, cheaper, and more reliable feedback about their category, brand, and competition. Let them know they can ask questions and get instant answers. Or listen in on ongoing conversations.” It's called Twitter and Facebook. It's called the customer reviews on Amazon or in the blogs. You know, the web.

The thing is, the best people in the business use research to generate ideas, not to judge them. They use it at the beginning of the whole advertising process to find out what to say. When it's used to determine how to say it, great ideas suffer horribly. Should your work suffer at the hands of a focus group, and it will, there isn't much you can do except appeal to the better angels of your client's nature.

What follows are some arguments against the reading of sheep entrails—or the subjective “science” of testing creative.

Testing sketches of ideas doesn't work.

Testing, by its very nature, looks for what is wrong with an idea, not what is right. Look hard enough for something wrong and sure enough you'll find it. I could stare at a picture of the world's most beautiful woman and in a half hour I'd start to notice, is that some broccoli in her teeth? Look, right there between the lateral incisor and left canine, see?

Testing assumes people react intellectually to advertising, that people watching TV in their living rooms dissect and analyze these interruptions of their sitcoms. (“Honey, come in here. I think these TV people are forwarding an argument that doesn't track logically. Bring a pen and paper.”) Both you and I know their reactions are visceral and instantaneous.

Testing is inaccurate because customers simply do not know what they'll like until they see it out in the world. Steven Jobs said, “People don't know what they want until you show it to them. That's why I never rely on market research.”5 Then there's screenwriter William Goldman's famous observation about movies: “Nobody knows anything.” Meaning, nobody in Hollywood knows what works. If they did, every movie would be a blockbuster.

Testing rewards advertising that's happy, vague, and fuzzy because happy, vague, and fuzzy doesn't challenge the viewer.

Testing rewards advertising that's derivative because a familiar feel will score higher than advertising that's unique, strange, odd, or new—the very qualities that can lift fully executed advertising above the clutter.

If testing the tone of a video or commercial is important to a client, testing is inaccurate because 12 colored pictures pasted to a board will never communicate tone like the actual film footage, voice-over, and music.

Testing, no matter how well disguised, asks regular folks to be advertising experts. And invariably they feel obligated to prove it.

Finally, testing assumes we really know what makes advertising work and that it can be quantifiably analyzed. You can't. Not in my opinion. It's impossible to measure a live snake.

Bill Bernbach said, “We are so busy measuring public opinion, we forget we can mold it. We are so busy listening to statistics that we forget we can create them.”6 This simple truth about advertising is lost the minute a focus group sits down to do its business. In those small rooms, the power of advertising to affect behavior is not only subverted, it's reversed. The dynamic of a commercial coming out of the television to viewers is replaced with viewers telling the commercial what to say.

These arguments, for what they are worth, might come in handy someday, especially if you have a client who likes the commercial you propose but has to defend poor test scores to a management committee.*

Science cannot breathe life into something. Dr. Frankenstein already tried this.

David Ogilvy once said research is often used the way a drunk uses a lamppost: for support rather than illumination. It is research used to protect preconceived ideas, not to explore new ones.

Another way research can be used poorly is what I call permission research. This happens when agencies show advertising concepts to customers and ask if they like them or not. (“Man, it would be really great if you guys like this, because then we can put it on TV. C'mon, whattaya say?”)

What's unfortunate about permission research is it's often used by clients and agencies to validate terrible advertising. Yes, it all looks and sounds like science, but as prudent as such market inquiries appear on the surface, the argument is specious—because the very process of permission research and all its attendant consensus and compromise will always grind ideas into either vanilla or nonsense.

As an example of permission research, I cite an interesting and very funny study done in 1997 by a pair of Russian cultural anthropologists—Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid.7 With tongue firmly planted in cheek, these two researchers set out to ask the public, “What makes for a perfect painting? What does a painting need to have for you to want to hang it in your home?”

They did many tests and hosted hundreds of focus groups all over the world. Their findings, meticulously prepared and double-checked with customers were as follows: 88 percent of customers told them, “We like paintings that feature outdoor scenes.” The color blue was preferred by 44 percent of respondents. “Having a famous person” in the painting got the thumbs-up from a full 50 percent. Fall was the preferred season. And animals! You gotta have some animals.

All this research was compiled, and an actual painting was commissioned. The final “art” that came out of the lab (to nobody's surprise) was very bad, as you can see in Figure 16.3.

Figure 16.3 Here's what happens when you ask focus groups to art-direct a painting. And yes, that's George Washington standing to the left of a modern-day family.

The point? Research is best used to help craft a strategy, not an execution. As someone once observed, “You cannot paint the Mona Lisa by assigning one dab each to a thousand painters.”

To end on a positive note. These research companies make money by selling fear to clients. But as advertising campaigns evolve out of traditional media and into forms that can't be presented to focus groups, this may change. The day clients begin to realize you can't measure a live snake, the fear mongers will hold less sway over the business. (Knock on wood.)

PROTECTING YOUR WORK.

Well, so much for research. If your concept manages to limp out of the focus groups alive, congratulations.

But even if your idea fares well in tests, if it's new and unusual the client is still likely to squirm. They may begin suggesting “minor changes.” The Chinese call this “the death by a thousand cuts.”

Minor changes kill great ideas, very slowly and with incredible pain. Less experienced clients are particularly good at asking you to take out “the load-bearing beam,” that one thing holding up the entire idea. By the time they've inflicted their thousandth minor change, both you and your idea will be begging for a swift bullet to the head. Sometimes you're going to need to deliver that bullet yourself. If one too many client changes have hurt your original idea, pull the trigger.

Base your defense on strategy.

Your client is not sitting at his office right now twiddling his thumbs, waiting for you to bring in your campaign. Marketing directors for consumer products companies may spend as little as 5 percent of their time on advertising issues—the balance on manufacturing, distribution, financing, and product development. In fact, the managerial strengths that got them to the job in the first place likely had nothing to do with an ability to judge advertising.

Keep this in mind when you go in to present: it isn't a client's job to know great work when they see it. They're generally numbers people.

Copywriter Dick Wasserman put it this way: “Corporate managers are inclined towards understatement. They value calm and quiet, abhor emotional displays, and do everything possible to make decisions in a dispassionate and objective manner. Advertising rubs them the wrong way. It is simply too much like show business for their taste.”8

Presenting an intangible idea to some clients is like selling an invisible magic poetry machine to scientists. They can't see this imaginary machine, it sounds expensive, it all feels so magical and weird, and they're pretty sure they don't like poetry anyway.

To prevail with an audience like this, Alastair Crompton says, “Think like a creative person, but talk like an accountant.”9 Don't defend the work on emotional grounds or on the creativity of the execution. (“This visual is, I'm tellin' you, it's monstrous. It kills.”) Instead say, “This visual, as the focus groups bear out, communicates durability.” Base your defense on strategy.

You must be able to strategically track, step by step, how you arrived at your campaign. This means having all the relevant product/market/customer facts at your fingertips. There's no such thing as bulletproof, but your ideas might be able to dodge a few rounds if you can keep the conversation on strategy alone. After all, strategy's something the client had a hand in authoring. It's often a tough thing to do but let the work's creativity speak for itself.

Do not try to solve the problem in the meeting.

When a client asks you to make a change, you aren't required to either fix it or refute it there in the meeting. Be like that repair guy you see in the movies. Blow your nose, scratch yourself, and say, “Well, looks like I gotta take ’er back to the shop.”

Seriously. It's tempting to want to alleviate client concerns by fixing something on the fly right there in the presentation. If it's an easy and obvious one, well, go ahead. But resist the temptation to do any major work there in the room.

Listen carefully. Write down their issues. Play the concerns back to them so you know you have it right and they know you heard them. And then say, “Okay, let us huddle up and get back to you.”

In The Creative Companion, David Fowler put it this way:

For now, listen to the input you've received and solve the problem on the terms you've been given. Your anger is beside the point right now. Once you've proven you're a trooper by returning with thinking that follows the input, you can bring up your original idea again. It may get a better hearing the second time. Then again, it may have been a [bad idea] all along. Or, most likely, you'll have forgotten all about it, because you're onto something better.10

Over the years, I've heard clients bring up the same issues time and again. Here are a few of them.

Somebody asks to cram more stuff into the idea.

Clients often ask for an ad to tout their full line of fine products. Who can blame them? The page they're buying seems roomy enough to throw in five or six more things besides your snappy little idea, doesn't it? But full-line ads are effective only as magazine thickener, nothing else.

The reason is simple. Customers never go shopping for full lines of products. I don't. Do you? (“Honey, start the car. We're going to the mall to buy everything.”) Customers have specific needs. It stands to reason ideas addressing specific needs are more effective. There's that old saying, “The hunter who chases two rabbits catches neither.”

So, if your clients say they have three important things to say, tell them they need three ads.

Somebody says, “Negative approaches are wrong.”

Well, you can start by pointing out that what they just said was negative but communicated their position quite respectably. But there are some other rebuttals you can try.

Take a look at the photograph reprinted in Figure 16.4. It's a very positive image, isn't it? There's happiness and cheerful camaraderie all around, and everybody's enjoying the client's fine product. It's also so boring I want to saw off my right foot just so I can feel something, feel anything.

It's boring because there is no tension in the picture. No question left unanswered. No story. No drama. And consequently, no interest.

Perhaps you could begin by explaining to them all that stuff we talked about in Chapter 7. About conflict and storytelling. The most basic tenet of drama (and we are indeed in the business of dramatizing the benefits of our clients' products) is conflict. The bad guy (competition) moseys into town, kicks open the saloon door, and Cowboy Bob (your client) looks up from his card game.

Conflict = drama = interest. Without it, you have no story to tell. And consequently, no interest.

Figure 16.4 Q: “Why can't you ad people do something positive?” A: This is why.

The brutal truth is that people don't slow down to look at the highway; they slow down to look at the highway accident. That doesn't mean we're all morbid rubberneckers. We're simply wired to scan for interruptions to the status quo and when trouble and conflict happen, they show up brightly on our radar.

The thing to remember about trouble and conflict in a commercial is this: as long as your client's product is ultimately portrayed in a positive light or is seen to solve a customer problem, the net takeaway is positive.

As Tom Monahan pointed out, “The true communication isn't what you say. It's what the receiver takes away.”11

Somebody asks, “Why are we wasting 25 seconds of our TV spot entertaining people?”

Other ways clients ask this is, “Can we mention the product sooner?” Or “Can't we just get to the point?”

This happens because many clients mistakenly believe people watch television to see their commercials. (“Honey, get in here! The commercial's about to start!”)

There is no entitlement to the customer's attention. It is earned.

And make no mistake, we're not starting from zero with customers. Thanks to Whipple, Snuggles, and Digger the Dermatophyte Nail Fungus, we're starting at less than zero. There is a high wall around every customer. And every day another brick is added.

You need to get your clients to see that “wasted” time in the spot is in fact the active ingredient in a good commercial. You're not welcome until customers like you. And they won't like you until they listen to you. And they won't listen to you if you open your pitch with bulleted copy points of your product's superiority.

If you look at advertising in terms of the ol' door-to-door salesman analogy, we can't just dispense with knocking on the door. Clients who say “let's lose all that entertainment stuff” are really saying: “Forget the introducing ourselves at the door. Forget that doorbell crap, too. In fact, let's just jimmy the lock with a brochure and barge into the kitchen with a fistful of facts. We'll make ’em listen.

You can't. You're not welcome until they're interested in you.

The best defense: Educate clients with examples of great advertising.

Your clients did not go to a portfolio school, or an art school, and probably never read one book on advertising. This is not a failing because understanding what makes great advertising isn't their job. Many clients achieved their position in marketing by being good salespeople in the field. You got your job by studying great campaigns and becoming good at using words, pictures, and technology to make interesting things. The issue here is how to close this gap.

The question I hear most from students and audience members is, “How can we get our client to start buying better work?” The answer: educate them. Show your clients what great work looks like. Send them links to great examples from the One Show, D&AD, Cannes, and lovetheworkmore.com. Or a subscription to Communication Arts. Take them to your local American Advertising Federation awards show. Share your excitement about what brilliant advertising looks like.

Outlast the objections.

I hope having one or two of these counterarguments in your quiver helps you save an idea one day. But the reality of this business is much of the time nothing you say is going to pull a concept out of the fire. If a client doesn't like it, it's going to burn.

The reasons clients have for not liking an idea often defy analysis. I once saw a client kill an ad because it pictured a blue flyswatter. Why the client killed it, he wouldn't say. “Just consider it dead.” When pressed for an explanation months later, he implied he'd had a “bad experience” with a blue flyswatter as a child. The room grew quiet, and we changed the subject.

So, get ready for it. It's gonna happen. I wish I could tell you why, but in a world full of all kinds of phobias (fear of germs, fear of spiders), apparently there's no fear of mediocrity.

All is not lost, though. You have one last weapon in your arsenal: persistence. I once read the definition of success is simply getting up one more time than you fall.

To that end, I urge you to simply outlast the clients. I don't mean by digging in your heels, but by rolling past their resistance, like a stream around a rock. I once did 13 campaigns on one assignment for a very difficult client. Thirteen different campaigns over the period of a year, and each one was killed for increasingly irrational reasons. But each campaign we came back with was good.

They kept killing them, but they killed the campaign only 13 times. The thing is, we presented 14.

PICKING UP THE PIECES.

There's always another idea.

Instead of fighting to save an idea, here's another thought. After you come up with an idea, do what Mark Fenske told me. “Pat it on the rear and say, ‘good luck, little buddy' and send it on its way.”

Mark believes you shouldn't make a career of protecting work. Alex Bogusky has said the same thing. He says the agency is an idea factory. “You don't like this one? Fine. We'll make more.” Maybe they're right. In the end, perhaps the best way to work is this: come up with the best idea you can and walk away. There's going to be another opportunity to do a great idea tomorrow.

Once work is approved, don't lose vigilance.

I find when I've sold an idea I didn't think would ever sell, I become so happy I lose my critical faculties and blithely allow the idea to wander off into production unescorted. I forget to follow through and keep sweating the details.

Moral: don't fumble in the end zone.

Don't get depressed when work is killed.

The work you come back with is usually better. And when you're feeling down in the dumps, remember nothing gets you back on your feet faster than a great campaign.

Sometimes the playing field changes when a campaign is killed. For one thing, you know more now about what the client wants. Also, you'll probably be left with a shorter deadline. A curse, but a blessing, too. If the media's been bought and time is running out, the client may have to buy your idea. So, make it great.

If the client doesn't buy number two or three or four, hang in there. The highs in the business are very high and the lows very low. Learn not to take either one too seriously.

James Michener once observed, “Character consists of what you do on the third and fourth tries.”

After you've totaled a car, you can still salvage stuff out of the trunk.

Okay, so the client killed everything. But you know what? You can still get something out of the deal.

If you're part of the presentation, you can at least improve your relationship with the client. I don't think there's any client who actually enjoys killing work. Ask any creative director about killing work; it's easier to just say yes and avoid the confrontation. The client likely knows you've worked hard on it.

If you can take the loss like a professional and still sit there and be your same funny self and ask, “Okay, so what is it we need to do here?” you will build rapport. Clients will admire your grit and trust you more the second time around.

If you're not producing agency work, do freelance.

Some agencies don't like it. They figured they invited you to the dance, so you should dance with them. But you do have to watch out for yourself. You need to keep adding to your portfolio. So, if you find yourself in an agency that's producing only meeting fodder and rewrites, maybe it's fair to flirt with a small client who needs a few ads. Just don't pin them up in the company break room.

Not only will doing the occasional freelance campaign keep your book fresh, it can keep your hopes alive during a bleak stretch and keep you excited about the possibilities of this business.

Keep a file of great dead ideas.

I called mine “the Morgue” and referred back to it many times, sometimes reanimating old ideas, every so often for the same client who originally killed them. Just don't make the mistake I did.

Here's what happened. My agency had two big bank clients. Bank A killed an idea I'd presented to them, so I sold it to Bank B. Two weeks later, Bank A calls and says, “You know that idea you showed us? We've decided we like it.” How the poor account teams on Banks A and B got us out of that fix is lost to history.

Anyway, most creative people do all their concepting in big, fat, blank books. Once they're full, we keep ’em handy on the shelf. Nothing gets thrown away. Except by clients.

NOTES

- 1. From GS+P’s Master Class series. https://www.masterclass.com/classes/jeff-goodby-and-rich-silverstein-teach-advertising-and-creativity/chapters/goodby-s-rules-for-creative-vandalism.

- 2. Ron Hoff, I Can See You Naked (Kansas City, MO: Andrews & McMeel, 1992), 30.

- 3. Thomas Kemeny, Junior: Writing Your Way Ahead in Advertising (Brooklyn: Powerhouse Books, 2019), 133.

- 4. Tom Monahan, Communication Arts, May/June 1994, 29.

- 5. Dave Smith, “What Everyone Gets Wrong about This Famous Steve Jobs Quote, According to Lyft’s Design Boss,” Business Insider, April 19, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/steve-jobs-quote-misunderstood-katie-dill-2019–4.

- 6. Bill Bernbach, Bill Bernbach Said … (New York: DDB Needham, 1995).

- 7. Alexander Melamid and Vitaly Komar, Paint by Numbers: Komar and Melamids Scientific Guide to Art, ed. JoAnn Wypijewski (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1997).

- 8. Dick Wasserman, That’s Our New Ad Campaign? (New York: New Lexington Press, 1988), 3.

- 9. Alastair Crompton, The Craft of Copywriting: How to Write Great Copy That Sells (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1979), 166.

- 10. David Fowler, The Creative Companion (New York: Ogilvy, 2003), 3.

- 11. Tom Monahan, Communication Arts, September/October 1994, 67.

- * For more information about the pitfalls of testing concepts, I refer you to Jon Steel's excellent book on planning, Truth, Lies, and Advertising: The Art of Account Planning (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998). In particular, I direct you to Chapter 6, “Ten Housewives in Des Moines: The Perils of Researching Rough Creative Ideas.”