16

Getting It Together in Your Company: A Practical Guide

Your head is likely spinning at this point with the daunting challenge of implementing the teachings of this book in your organization. For those lower in an organization, the AccuWiz vision may seem like an impossible dream. Change can be implemented with the aid of an incremental project plan that builds on small successes using the organizational behavior model to influence and sustain change.

There are eight steps to implement your Investment roadmap:

- Organizational support

- Stakeholder value analysis

- Stakeholder research

- Stakeholder interviews

- Investment candidates

- Initial roadmap

- Investment planning

- Consequence alignment

The objectives are to establish an initial Investment backlog and roadmap and then instill the practices necessary to manage it. The initial steps can be accomplished without risk and minimal use of resources to establish credibility and support for the overall initiative.

16.1 Step 1: Organizational Support

There are three key decision‐makers in your organization who must come onboard. They are the product management leader (VP/director of product management), engineering leader (VP/director engineering or CTO), and your PMO leader if you have one (head of program or project management). If you are lower in the organization, there may be several management levels that you need to get on your side before getting to these higher‐level positions.

Everyone is suspicious of the person who has just experienced an epiphany from reading a book or attending a seminar. Most people can't contain their excitement and overwhelm others by condensing what they learned over days or weeks into sound bites. You can take a strategic approach to influence decision‐makers with your new insight into organizational behavior principles.

Some say that people are naturally resistant to change. I disagree. If I were to give someone one million dollars, would they be resistant to that change? Of course, not. People resist change when they anticipate negative personal consequences. We know that positive consequences can be used to reinforce the desired behaviors necessary to support change. So don't expect that just evangelizing in terms of general and longer‐term nebulous consequences is going to get you anywhere. You want to identify the frequent consequences for the key decision‐makers.

I recommend you start by understanding and addressing the organizational consequences for product management, engineering, and project management leaders from whom you will need support. The key point is that whenever you are “selling” the idea to anyone, it should be in terms of the consequences they experience on a daily or weekly basis, not how the idea benefits you or the organization.

Although you may not like the term “selling,” this is what one must do to gain support for a major initiative. We know from marketing that people will buy when a product or solution provides a benefit or reduces a pain point. You can now recognize that benefits create positive reinforcement, whereas pain points are negative reinforcement.

Pain points tend to work better at higher levels in the organization because losing one's position is the overwhelming negative consequence (sadly, this often means that the best management tact is to lie low and do nothing!). I also think people react more quickly to reduce pain points. It's probably related to our strong survival instincts. The ability to reduce a significant pain point will spur purchasing behaviors.

Table 16.1 provides typical pain points for individuals in a product development organization and how the Investment model addresses each of them. They also provide an example of how the organizational behavior model can be applied to roles within your organization to understand and change behavior.

16.1.1 Influence Strategy

I hope the pain point exercise provides insight into how consequences drive behavior of product leaders in your organizations, and why they are unlikely to change if Waterfall planning persists. You may be able to think of other pain points, but the analysis will suffice to develop your strategy. Either way, the reason leaders in product development behave the way they do shouldn't be a mystery any longer.

Table 16.1 Organizational consequences by role.

| Pain point | Frequency | Investment approach |

|---|---|---|

| Engineering leader | ||

| Pressure from product management to add features beyond development capacity | High – saying no often results in escalation and pressure from the CEO, often with career implications | WSJF prioritized backlog and roadmap managed collaboratively by product management and engineering |

| Criticism for missed schedules | High – often occurs in every project or program review and executive staff meeting | Investment planning with fixed schedule and financial objectives and variable scope |

| Complaints from staff of pressure from product and project management | Medium – engineers express frustration by fixed schedule and content that precludes Agile the way they were taught | Agile with flexible content allows engineers to set and meet their own sprint goals |

| Product management leader | ||

| Saying no to sales | High – in organizations still using Waterfall planning | Investment backlog prioritized by WSJF with one‐year WIP limit |

| Product managers complain of no time to plan | Medium – product management leaders often express this frustration | Separate planning and implementation roles for product management and product owners. Investment model provides framework for planning |

| CFO, CEO, or PMO criticism for missed schedules | High – often occurs in every project or program review and executive staff meeting | Investment planning with fixed schedule and financial objectives and variable scope allow schedules to be met |

| Project/program management | ||

| Missed schedule, content, and/or budget | High – takes blame from CEO and CFO for being off target at project or program reviews | WSJF prioritized backlog and roadmap managed collaboratively by product management and engineering. Engineering and product management are accountable for achieving Investment objectives |

There are some key observations. The first observation is that most of the behaviors in larger organizations are driven by negative reinforcement, which becomes more significant as job levels increase. Most actions take place to avoid punishment. On the other hand, positive consequences are usually uncertain and long delayed and do not outweigh negative reinforcement.

The second observation is that the engineering leader has the most severe and frequent negative consequences and has the most to gain from introducing the Investment approach. The engineering leader is the ideal executive‐level sponsor for the change. Unfortunately, they usually have less political power compared to their product management and PMO peers.

The next most likely ally of engineering is the PMO, if you have one. They are usually frustrated by being in the difficult position of trying to deliver feature‐level predictability with Agile development. They will welcome a solution that allows them to achieve predictability.

The product management leader can be a major obstacle. Many product managers have found a comfortable position with little accountability. Most are not accountable for profit and loss (P&L) results because there are so many factors that change by the time releases are widely deployed, and schedule surprises are always the fault of engineering and project management. Your most substantial leverage occurs when your product management department is driven by an insatiable, hard‐charging sales department. I've been there as a VP of product management. Focus on that consequence. Product management will likely welcome a way to manage their sales stakeholders.

The last potential influence strategy is the “nuclear option.” The CEO and CFO are usually frustrated by the lack of visibility and predictability of software development relative to the predictability of manufacturing or operations. The CEO or CFO is a last resort because it may increase resistance from people below. However, the CEO and CFO have the power in the organization to initiate change. Ideally, the heads of product management, engineering, and project management jointly pitch the new planning methods to the CFO and CEO, but alignment can be achieved from the top if necessary to get product management onboard.

Now, you know how to gain support for change in your organization. The next step is to recommend a low‐risk, low‐effort exercise to demonstrate the relevance and value of the Investment approach for your organization.

16.2 Step 2: Stakeholder Value Analysis

A preliminary stakeholder analysis is a low‐effort, low‐risk next step. It will likely show that product management is so deep in functionality that they miss customer value. You can facilitate this yourself if you are a product manager. If not, propose a morning or an afternoon session that can be facilitated by a product manager. Product management can learn a useful technique for getting down to core customer value. The process enables product managers to get above mundane feature‐level requirements to generate customer value as professional product managers. It's a small investment in time with the potential for very high payback. The benefits of focusing on value should become apparent.

The facilitating product manager should read Chapter 6 of this book. Study the examples and use the same categories and stakeholder table formats (e.g., internal versus external stakeholders). Invite senior engineers to let them contribute to Investment planning.

Start the meeting by creating a complete list of product stakeholders using the categories in the examples. The rules are the following:

- A product stakeholder is a role that gains benefit from your product.

- Include constrainers who can influence or impose requirements.

- Define stakeholder classes for those with the same role and different requirements.

- More is better at this point. Stakeholder roles can be collapsed if the values and requirements turn out to be the same.

The initial experience will reveal that engineers and product managers are challenged to think in terms of value instead of functionality. Most of the initial value suggestions will be functional requirements. Here are some examples from sessions I have facilitated:

- “I want additional reports to see late invoices.”

- “I want a stable system to integrate with.”

- “I want faster response time to get my work done.”

The flag here is that they all imply functionality. They are not at the level of value. Further discussion and application of the “Five Whys” lead to the underlying values:

- “I want to reduce outstanding cash balance to meet or exceed my performance objectives.”

- “As a partner, I want to maximize our integration profits.”

- “I want to achieve higher throughput to meet or exceed my performance objectives.”

The above are good examples of the difference between user stories and epics. Value statements are higher level than user stories. They are like epics, but they relate to business or individual performance objectives – the root driver of organizational consequences.

The key to successful facilitation is to continually screen value statements in terms of the following characteristics to know when you have reached the underlying value:

- Not a feature or requirement

- Does not imply or constrain implementation

- Supports business or personal performance objectives

- Is measurable

It takes some practice, but persistence and continuously cross‐checking with the above-listed criteria will get you there.

My experience is that participants are initially struck by the sheer number of job titles to which their product adds value. They usually find that the values of internal stakeholders who support the product were not being considered. They also see that the values are different at each job level and are usually supportive of the next highest level. Satisfying the value of an influencer can create customer evangelists for your product. However, the attendees recognize that product success depends on ultimately addressing the values at the executive level with a proxy business case described in Chapter 10.

Focusing on the values of each stakeholder guides a deeper level of discussion and leads to common understanding. You will likely hear many comments of, “I didn't know that.” Product managers are often surprised by the stakeholder values contributed by senior engineers who have worked on the product for years. Engineers often feel that a veil of secrecy has been lifted with new access to market and customer information.

The stakeholder value exercise results in a concise picture of opportunities to add value for which customers will be willing to pay. Just as importantly, the exercise reveals information that should be known but isn't. This provides the basis for stakeholder research and interviews described in the following sections.

The session output can be shared as a living document for engineers and product managers. Stakeholders and their values don't change frequently within a market segment. What a great way to onboard new product managers and engineers to rapidly sensitize them to your market and customers.

The last word of advice is that you should consider using a professional facilitator and provide them with the stakeholder value criteria to lead the discussion.

16.3 Step 3: Stakeholder Research

This step involves more resources. The work can be done on a part‐time basis without impacting business commitments by using effective positive reinforcement. Presumably, stakeholder analysis has produced sufficient intrigue to gain support from above. Presenting the results of the stakeholder analysis to the key decision‐makers can garner executive‐level support to provide the resources.

The stakeholder analysis will likely identify large gaps in customer and market knowledge. As opposed to general untargeted market research, a product manager can now focus on specific stakeholder values. Most product managers are surprised at how much information can be mined from the web with focused searches. The trucking proxy business case used earlier in the book showed that I could quickly find detailed data on US trucking operational costs. Credible data can often be found on the web, or reports can be purchased from market analysts. Start with the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and stakeholder values of the key decision‐makers.

You may want to pair each product manager with a senior engineer who has product interest beyond implementation. Doing this sets the tone for business and technical collaboration fundamental to the Investment model and demonstrates the value of technical input early in product planning. Recognize that being involved at the business level will not be of interest to many engineers. Many want to remain technical. You can usually find senior engineers who view involvement in planning as career development or have just been dying to have their product ideas heard. Market awareness and business involvement can be criteria for your technical ladder. Engineers can grow in both business and technical directions without having to become product managers who soon become technologically stale. You may even consider a title of “Product engineer.”

The other purpose of this research stage is to prepare for stakeholder interviews in the next step. Interviewers should be able to show that they have done their homework before taking a stakeholder's valuable time. Preparation of questions to fill in the gaps will result in a more concise and effective interview.

This section began with the importance of effective positive reinforcement to engage product managers and engineers. Set up weekly review meetings where the teams can present what they have learned about stakeholder value. Be sure to recognize incremental progress.

16.4 Step 4: Stakeholder Interviews

Identify a subset of product stakeholders who can provide insight into how a specific value impacts their success. Prepare a set of questions based on the research done in the prior step.

Drill down with the “Five Whys” technique to the point where value can be measured. Steer the discussion to value when functionality comes up. You've reached your objective when you can recite a few simple value statements that do not constrain functionality. Stakeholders will usually respond with an enthusiastic “yes” when you hit the mark.

16.5 Step 5: Investments

This is the fun part – an opportunity for creative brainstorming. A half‐day meeting is set up with the participants in the stakeholder value exercises and anyone else you feel could contribute ideas. Again, business and technical fusion is important. Consider inviting others outside of product development, such as operations, support, or IT. The only requirement is that they have reviewed the stakeholder value analyses and the stakeholder interview presentations.

There are numerous brainstorming techniques that can be used, like storyboarding and mind mapping. There may be a common approach used in your organization. If not, bring in a professional facilitator for the meeting. I'm always impressed by how a good professional facilitator can lead a group to creative results without being familiar with the domain.

The purpose of the meeting is to identify opportunities to significantly increase stakeholder values. It starts at the top with the decision‐maker values and then proceeds to the influencers. Recall our definition of great products introduced in Chapter 6:

The common trait of “great products” per Brooks' definition is that these organizations focus on something their stakeholders' value and move it a mile rather than moving everything an inch at a time with features and small enhancements.

The best possible case is that you move a key decision‐maker value by a mile to differentiate your product. However, that's not always possible. The next best thing is to provide a quantum leap in value for one or more influencers. For example, spreadsheets weren't originally justified based on bottom‐line savings. They provided a leap in value beyond methods currently available to create a groundswell of support.

Each value should be examined for the potential to “hit one out of the park” to encourage out‐of‐box thinking. You may not find one, but the ideas generated will often lead you to solutions with value customers will pay for.

16.5.1 User Scenarios

User scenarios provide the vehicle for business and technical collaboration and lend themselves well to brainstorming. Clarify the definition of user scenarios at the beginning of the meeting to avoid getting into user stories or use cases. Again, a professional facilitator can help.

Table 16.2 ATM use case example.

| Prior state | Stimulus | System action | Final state |

|---|---|---|---|

| Start | User inserts card | Request PIN | Waiting for PIN |

| Waiting for PIN | User enters correct PIN | Displays transaction options | Waiting for transaction selection |

| Waiting for transaction selection | User selects withdrawal | Requests withdrawal account | Waiting for account selection |

| Etc. | |||

User scenarios are descriptions of what one would observe a stakeholder doing for one transaction with the system. You can consider them as a description of a success path use case from the initial state to the final state without the alternate and error cases.

Let's make a distinction between use cases and user scenarios. Use cases are broken into small steps between stable system states. The system waits for a stimulus to move from one stable state to another. The stimulus is an event triggered by a user, or a system timer.

For example, Table 16.2 shows ATM use cases for the first few transactions of a successful withdrawal.

You can see that use cases are very detailed, so the big picture is often missed, and the example above doesn't include error or alternate cases yet. A group creating use cases for an Investment will spend their time debating minutia instead of coming up with innovative approaches.

A user scenario is a paragraph describing an end‐to‐end transaction without considering intermediate system states. For example:

The bank customer inserts their card into the ATM. They enter their PIN. The system displays the customer accounts to select. The customer enters the withdrawal amount. The system returns the bank card. The user removes their card, and the system disperses the cash.

Use cases have their place in requirements analysis, but user scenarios are a useful brainstorming tool to produce a high‐level description of system functionality. Scenarios can rapidly be improved through brainstorming.

User stories have their place in Scrum to break down epics into what can be demonstrated within one sprint. In theory, epics and stories are supposed to describe the problem to solve and not constrain functionality. In contrast, user scenarios introduce innovative functionality at this early stage that can be suggested and vetted by the business and technical meeting attendees. Ideas for leveraging technology are welcome.

16.5.2 Feature Definition

It is possible to move directly from user scenarios to epics and user stories. However, most organizations use features as increments of functionality that convey benefit. Investment burndown charts can be at the feature level to forecast those that will be included in the Investment by the target end date.

Feature definition can be another group exercise using the user scenarios as input. However, feature discussions don't center around what someone just thinks is a good idea. Features must be justified in terms of how they contribute to the income generation goals of the Investment. T‐shirt sizing, where business value represents contribution to income, is used to prioritize features and determine a reasonable cutoff point. The team is incented to minimize features because adding features increases cycle time and lowers Weighted Shortest Job First (WSJF) priority.

16.5.3 WSJF Screening

Rank the Investment candidates based on WSJF considering potential income and cycle time. Development effort can be used as a proxy for cycle time at this level of planning. Allocate 200 points that each attendee can use to assign across all Investments. They can spread 100 points separately for three‐year income and 100 points for cycle time. Allow them to explain their reasoning for their allocations, followed by group discussion. Let them make any adjustments.

Sum the points for three‐year income and cycle time separately for each Investment and divide three‐year income points by cycle time points to estimate WSJF. Order the list by descending WSJF. Continue to score and truncate the list until you have a manageable list.

Look for large deviations in the scores among Investments. This often reflects different assumptions by the scorers. Discuss why they are so different and make any adjustments. Take some time on each Investment to brainstorm how income could be increased and development cycle time reduced. The value of this ranking exercise is the discussion and common understanding it generates, not to arrive at exact numbers.

For example, assume four participants allocate their points to three‐year income as in Table 16.3. Points are proportional to estimated income.

Table 16.3 Three‐year income point weighting example.

| Investment | Score 1 | Score 2 | Score 3 | Score 4 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment 1 | 30 | 25 | 15 | 30 | 25.0 |

| Investment 2 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 25 | 17.5 |

| Investment 3 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 30 | 11.3 |

| Investment 4 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 5.0 |

| Investment 5 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 7.5 |

| Investment 6 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 10.0 |

| Investment 7 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 20.0 |

| Investment 8 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 3.8 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Table 16.4 Preliminary investment WSJF ranking.

| Investment | Income | Cycle time (weeks) | WSJF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investment 7 | 20.0 | 3.5 | 5.7 |

| Investment 1 | 25.0 | 5.2 | 4.8 |

| Investment 3 | 11.3 | 5.5 | 2.0 |

| Investment 2 | 17.5 | 20.0 | 0.9 |

| Investment 5 | 7.5 | 12.5 | 0.6 |

| Investment 6 | 10.0 | 20.2 | 0.5 |

| Investment 8 | 3.8 | 7.7 | 0.5 |

| Investment 4 | 5.0 | 25.4 | 0.2 |

The shaded rows are examples of significant deviation among the scores that should be discussed. Don't try to convince anyone to change their score, but make sure that everyone is working from the same assumptions.

The exercise is repeated for cycle time. Income contribution points have been divided by cycle time points to calculate WSJF in Table 16.4.

Don't pare the list at this point. Schedules will be estimated in Section 16.6. That will allow you to establish your Investment backlog one‐year Work in Progress (WIP) limit to determine the subset for detailed planning.

16.6 Step 6: Initial Roadmap

The initial roadmap is a challenging step because resource availability for Investments must be reconciled with current business commitments. Your sales and operations stakeholders should be involved because trade‐offs will need to be made between current roadmap targets and the Investment candidates. There will likely be pressure to include all the Investments as well as current commitments. This is where the value of the Investment approach is demonstrated. Your stakeholders will realize that they can benefit more from shorter development increments with higher value.

Start by making any changes in rank based on the updated WSJF values determined during Investment planning. Establish a payback period target if one doesn't exist. Two years is a good starting point to minimize risk. The downloadable Investment Income Profile Calculator spreadsheet can be used to calculate the annual income profiles based on Investment payback periods and development costs for each Investment.

16.6.1 Resource Allocation

The initial Investment roadmap will be based on current resource availability. There will likely be current commitments to be delivered in the next planned release, so work on the Investment backlog can't start immediately. However, the features in the release should be evaluated in terms of Net CoD impact on the Investment backlog. Reducing the size of the release will move quantifiable Investment income forward in time.

Some will be hard customer commitments that can't be changed. Other features can be assessed in terms of the Investment backlog Net CoD reduction relative to income lost if they are not included in the release. Upon careful evaluation, you will find that many of the discretionary features can be dropped to increase overall income.

The downloadable Investment Planning Schedule Calculator spreadsheet available at www.construx.com/product-flow-optimization-calculators can be used to forecast Investment schedules based on Full Time Equivalent (FTE) profiles. It should not be used at this time to fix Investment schedules. The spreadsheet does not account for resource specialization, so results should be viewed as the best possible case where engineering staff is interchangeable. Investment timeboxes should be reforecast by engineering after the initial Investment backlog prioritization. The spreadsheet allows you to quickly adjust FTE profiles to recalculate the Investment schedules. The Investment Backlog Net CoD Calculator is available in the same location. It allows you to calculate changes in Net Cost of Delay based on Investment delays.

16.7 Step 7: Investment Planning

Investment planning starts only for Investments that fall within the Investment backlog one‐year WIP limit. Planning involves completion of the Investment planning template introduced in Chapter 10. The key is to break it down into small increments as weekly goals for Investment owners. For example:

Week 1

- Proxy business case

Week 2

- KPIs

- Stakeholders

- Constraints

- Competition

- Acceptance criteria

Week 3

- Go‐to‐Market plan

Week 4

- Financial and development cost targets

- WSJF update

Week 5

- Assumption validation

Establish a weekly meeting with the Investment owners to allow them to present. Provide feedback and recognition.

Investment WSJF values are then updated based on the knowledge gained from completing the Investment templates. Investment timeboxes can be updated to provide reasonable schedule targets that incorporate sufficient feature contingency, as described in Chapter 7.

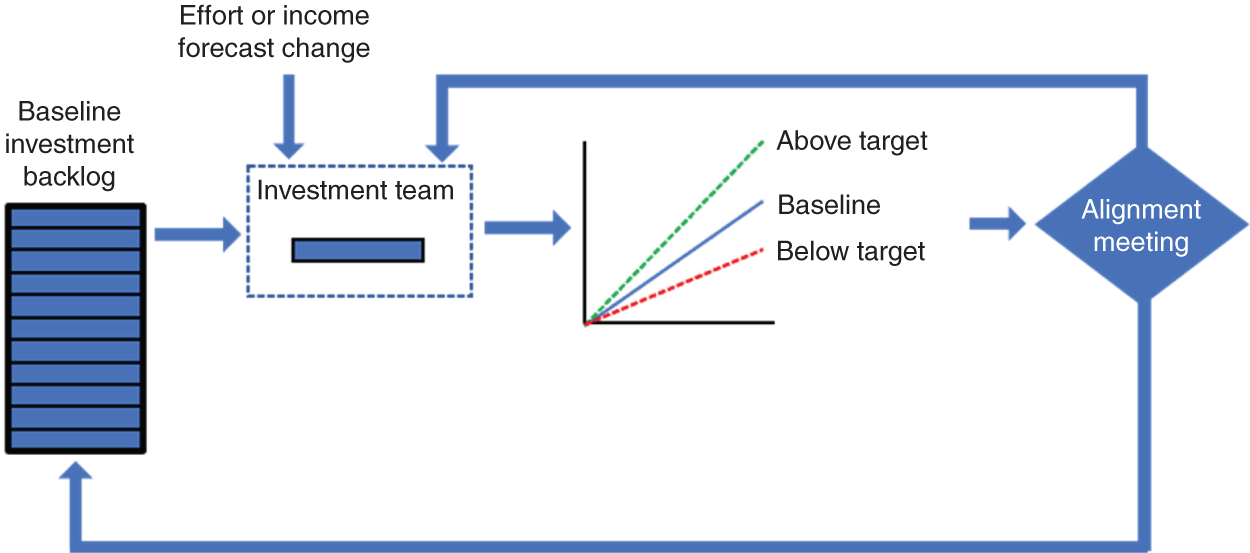

16.7.1 Agile Roadmap Alignment Meeting

The Agile roadmap is managed with the stakeholder alignment cycle depicted in Figure 16.1.

Figure 16.1 Agile roadmap alignment cycle.

This is the basic cycle used to achieve schedule and financial targets. The meeting should be weekly, or at least biweekly. Any changes that would impact baseline schedule and/or financial targets are identified by the Investment teams. They must present a comparison of any financial impacts with the baseline target. The team may be asked to go back and look at alternatives, such as dropping or simplifying features to stay on target.

The meeting is an important synchronization point to maintain roadmap stakeholder expectations. Even if change doesn't occur weekly, it's good to verify that assumptions are still valid. This is also an opportunity to raise risks that can be addressed proactively. The meeting would typically be led by the product management leader or P&L owner, and attended by project management, sales, and operations leaders.

Investment owners also present their feature burndown projections and financial forecast at each meeting. The following presentation template can be used:

Slide 1: Investment Summary

- Changes from last week

- Financial impacts

Slide 2: Mitigation

- Actions taken to minimize impacts

Slide 3: Alternatives and Recommendation

- Feature content or functionality reduction?

- Additional resources?

- Increased income?

- Investment delay?

Slide 4: Assistance

- Support required outside of team authority

Each alternative should include overall roadmap impacts, including cascading delays and associated Net CoD to facilitate decision‐making. A recommendation may be accepted or a recovery plan initiated. Any changes will be incorporated into the baseline roadmap only after the stakeholders agree on the changes and the financial and/or schedule impacts for the next review.

16.7.2 Program Review

There should also be a biweekly or monthly program review meeting at the release level. The objective of the meeting is to synchronize expectations for department‐level deliveries necessary for release deployment. It is also an opportunity to present ways in which release size can be reduced by releasing Investments on‐demand. In most large organizations, a project or program manager will be assigned to each release. They can take a broader program‐level perspective now because they are not involved with administrative task and feature tracking. The Investment schedules and release assignments are based on the baseline roadmap.

I use the term “program manager” instead of project manager to reflect the higher‐level focus on release business objectives. Program managers present their project plans showing all the dependencies necessary to take the release through commercial availability, including any planned field verification. Responsibilities are assigned at the department level. For example, the training department is responsible for creation and delivery of training for Investment stakeholders. Marketing is responsible for delivery of marketing collateral and sales training. Operations may manage the first deployment and verification.

Most mature organizations know how to do this. The difference is that current program reviews typically dwell on the software development minutia, often down to the task level. In this approach, Investments are the lowest‐level product development planning element, increasing focus on critical departmental‐level dependencies and risk management.

In addition to the program plan review, each program manager presents current obstacles to releasing each Investment separately. Reducing release cycle time by being able to deploy Investments independently is a major objective for the program managers. Cross‐functional management attending the review can contribute ideas and support to release Investments independently. For example, an Investment‐level pricing model may be introduced instead of being bundled within release pricing. Or perhaps additional development effort can be justified based on Net CoD savings from being able to deploy an Investment independently. The main objective is to maintain organizational focus on reducing release opportunity cost. Release bundling is a last resort.

16.8 Step 8: Consequence Alignment

Most organizations include “alignment of recognition and rewards” in their change management plans. Unfortunately, this usually just involves individual performance plans. We know from the behavior model that performance reviews have limited impact because consequences are long delayed. The Investment approach has been designed with an understanding that frequent positive consequences must be built into the work itself.

You will recognize that the roadmap alignment meeting incorporates a rapid consequence feedback loop. Additional features must be justified in terms of positive financial impact relative to the cascading roadmap Net CoD impacts. Dropping lower‐value features will shift income forward in time. For the first time, you can demonstrate how sales and operations can increase income by reducing features and functionality, moving closer to the illusive Minimum Marketable Feature Set (MMFS).

The roadmap meeting should be a collaborative and supportive meeting as opposed to what happens in many project reviews. The product management leader is responsible for maintaining an environment of positive reinforcement for Investment and technical owners. Presenters must see their management as empowering and supportive. Don't use the meeting to punish. If there are performance concerns, that's a private discussion with an individual's manager.

This may involve a significant behavior change on the part of the meeting leader to move from the left to right side of the motivation curve presented in Chapter 13. Those leaders who have attained success by getting results from negative reinforcement may find it difficult to change.

I hope the behavior model has convinced leaders that they must choose one side or the other to get organizational results. This takes strong leadership qualities. A strong leader will shield people from negative consequences. The leader should not expect to get the results described in this book if they are not ready to establish strong and frequent positive reinforcement in the daily work in their organizations. Empowering people without motivation reduces performance.

There are some methods that the meeting leader can use to help them make this transition. They can appoint a trusted individual who works for them to observe and provide feedback on the extent to which they are effectively applying consequences. It should be someone capable of providing frank corrective feedback after meetings in which they observe any resurgence of negative consequences. It could be an assistant who attends meetings to take notes.

Not everyone will be comfortable with asking for feedback from subordinates. That makes the change more challenging. Alternately, they can keep score during meetings by marking a note pad with an “x” for every time they apply threats or punishment, and a checkmark for positive reinforcement. Maintain a log with an objective of increasing positive reinforcement and reducing negative behaviors over time.

You won't have to do this forever. You will receive positive reinforcement for applying positive reinforcement when you see the results from increased engagement. As we know, positive reinforcement shapes behaviors that become habits.

Positive reinforcement needs to become the natural way of interacting with people you want to motivate. Some guidelines:

- Be specific so people know exactly which behavior is being reinforced. The impact of positive reinforcement is increased when people know that you know what they did, instead of the often meaningless “good job.”

- Reinforce during or as soon as possible after the desired behavior or result.

- Use metrics and charts as opportunities to reinforce. Shorter and more frequent goals provide more opportunity for positive reinforcement.

- Be sincere – don't say it if you don't mean it. People know.

- Apply negative reinforcement sparingly to get a behavior started and then positively reinforce the new behaviors and/or results.

- Personalize the reinforcement. For example, public appreciation may be punishment for some individuals where a personalized e‐mail can be very effective.

- Forget rewards – only a few people can win (usually the self‐motivated), while others are often disgruntled. You need to motivate the unmotivated using positive reinforcement to achieve high organizational performance.

These are all good techniques to increase the effectiveness of your positive reinforcement, but they don't replace the need for a leader to establish the environment for peer reinforcement. Consider the time spent interacting with your staff compared to the time they are working with peers. That's where positive reinforcement can be the most frequent and meaningful.

The roadmap alignment leader must be aware of how the behavior of others add to or subtract from positive reinforcement in the meeting. Punishment from an attendee can extinguish the effect of positive reinforcement. Be prepared to provide corrective feedback to attendees as needed after the meeting. It may even require removing certain people from the attendee list.

We've discussed consequences for Investment teams in the roadmap alignment meeting. What about the individual product managers and engineers working on an Investment? The good news is that if you have implemented the practices provided in this book, you will observe collaboration and teamwork. Product managers and engineers now have common goals for Investment schedule and financial results. Common goals foster collaboration, teamwork, and peer reinforcement.

Whether or not you are using Agile development, you need to create winners in your organization. You can't make a team act like winners. They must be winners to act like winners. Put an event on your calendar as the first thing you see at the start of every week with the following note.

What opportunities have I established this week for peer recognition for achieving shared objectives?

If the answer is, “none,” you are unlikely to ever see the incredible power of high‐performance teams.

16.9 Summary

- Gain organizational support for change initiatives by addressing the pain points of influencers and decision‐makers.

- Start with a low‐effort analysis of stakeholders using the methods described in this book. The exercise will provide valuable customer and market insights.

- Market research can now be focused on specific stakeholder values.

- Generate a potential list of Investment candidates. Use the point system to prioritize Investments based on WSJF.

- Free committed resources where possible by using Net CoD to show financial benefit of dropping low value features.

- Let the Investment owners create weekly targets for detailed Investment planning for Investments within the one‐year WIP limit. Recognize progress.

- Establish the Agile roadmap alignment meeting with roadmap stakeholders to frequently collaborate and synchronize expectations. Financial and schedule impacts of changes are reviewed before acceptance.

- Assign program managers at the release level to achieve release business objectives and to minimize release opportunity costs.

- The Agile roadmap meeting leader must accept the need to move to the strong and frequent positive reinforcement side of the motivation curve.

- The positive consequences to motivate self‐directed teams are inherent in Agile development freed from the constraints of Waterfall planning. Just support Agile the way it was envisioned.