14

Innovating with Investments

This chapter builds on two pillars of this book: The Investment model and the behavioral model of motivation. Investment stakeholder values focus innovation by providing engineers with the problem to solve instead of telling them what to build. However, innovation is scarce in most organizations even if the problems are identified. We'll show how the behavior model provides insight into why so few organizations are innovative, and how you can measure and increase motivation.

Let's begin with a vision of an innovative organization. You can think about whether this scenario would likely happen in your company. The chapter will then reveal what it takes to create a culture of innovation.

- Ken loves to go to work each day. He woke up at 3 a.m. with a great idea about how to significantly increase the stakeholder value on which the team has been focusing – enabling their product stakeholders to set up their system in hours instead of days. He learned about the opportunity from a discussion with their product manager where this challenge was presented. He's been thinking about it for days.

- Ken thinks it will be a major differentiator for the company. He gets his team together the next day to build on the idea. They love it and enthusiastically contribute improvements. They do a critical review the next day and make some tweaks to make it practical. It goes on the team's innovation Kanban board.

- The team suggests that Ken put a demonstration together for the next weekly team “Innovation Fest.” Ken's manager, Sharon, suggests they add some “innovation story points” to their next sprint to give Ken and the team time to create the demonstration. He presents at the Innovation Fest and receives a lot of great ideas for improvement, as well as recognition for his creative solution. The VP of his department told Ken how valuable the idea is to the company.

- Sharon tells Ken that she is going to elevate it directly to her VP‐level Kanban board and ask one of her directors to sponsor it. Sharon is also going to ask the product management department head if he can provide a product manager to work with Ken to help shape the idea into an Investment.

My guess is that this scenario is not likely to occur in your organization, unless you are one of the few companies that really does prioritize innovation, like 3M or Apple. For many of you, your engineers are under schedule pressure, so innovation is a rare topic.

This book has shown you how to define Investments that increase one or more stakeholder values that focus engineering on innovation. The Investment timebox approach with variable content can reduce schedule pressure that overrides innovation. However, the Investment model alone will not increase innovation. You can implement all the Investment practices to focus innovation without seeing any.

In addition to implementing the Investment model, organizations need to somehow create the nebulous “culture of innovation” in which ideas flourish and individuals translate their ideas into software that creates business value. This chapter builds on our organizational behavior model to provide the answer by addressing the question, “What motivates an individual to propose an idea at work and be willing to spend extra time to develop it into something useful for the organization?” The chapter will make a strong case that frequent positive reinforcement must exist for behaviors that lead to innovation. For example, volunteering an idea is a behavior. Creating a demonstration is a behavior.

Appendix E includes a survey based on an organizational behavior model of innovation. You'll be surprised at how a handful of questions can predict whether you are, or will ever be, an innovative organization.

This chapter ends with practical methods to create a “culture of innovation” in your organization.

14.1 Innovation – A Working Definition

Innovation is often discussed in the context of new products that revolutionize an industry, like the iPhone. Taking risk is a major topic because these big innovations require major Investments. The ideas and practices in this chapter can lead to revolutionary innovation, but most software organizations are just looking for ways to differentiate themselves from their competition with incremental innovation. Most companies today want to be the first to leverage leading‐edge technologies, which come from the engineering side.

There are other forms of innovation from which companies benefit. Process innovation is an example. Someone comes up with an innovative process or tool that reduces code defects by 30%, or a junior engineer figures out how to save 5000 lines of code by using an existing class library. These are innovations.

I usually start my talks on innovation by asking the group to volunteer their definitions of innovation. Responses vary:

- A good idea

- Something useful

- A new product

Innovation definitions abound:

The introduction of something new.

Merriam‐Webster Dictionary

A product, process or service new to the firm, not only new to the world or marketplace.

M. Hobday

The sequence of activities by which a new element is introduced into a social unit, with the intention of benefiting the unit, some part of it, or the wider society. The element need not be entirely novel or unfamiliar to members of the unit, but it must involve some discernable change or challenge to the status quo.

N. King

No wonder we find innovation such an abstract concept. We don't even have a uniform definition of what it is. Recall that great products were recognized for substantially increasing or adding value for a product stakeholder. Great products often spring from innovation where stakeholder value can be “moved by a mile.”

I use this definition for innovation:

Innovation is a non‐obvious improvement provided by a product, process or solution that results in a notable increase in product stakeholder value.

We learned how to determine stakeholder value in Chapter 6, and we found that stakeholder value can be measured on a scale.

There is a legal definition for “non‐obvious” used for US patents.

A patent for a claimed invention may not be obtained, notwithstanding that the claimed invention is not identically disclosed as set forth in section 102, if the difference between the claimed invention and the prior art are such that the claimed invention as a whole would have been obvious before the effective filing date of the claimed invention to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains. Patentability shall not be negated by the manner in which the invention was made.1

We certainly don't want to resort to legal arguments to define innovation, but the U.S. Supreme Court recognizes that is possible to determine nonobviousness. I prefer the “slap‐test.” Do you slap yourself on the forehead when you first see the innovation? We certainly recognize innovation when we see it.

Now that we know how to define it, how do you make it happen in your organization? It turns out that it's not that easy. It requires innovation processes and a top‐down culture change. You can't get there by just putting up innovation posters and having an annual innovation awards dinner.

14.2 Investments as an Innovation Vehicle

An article from USA Today reports the results of research by Accenture [1]:

Specifically, many employees think they have a good idea, but their managers won't listen to them. In their defense, managers say these ideas often are out in left field with no real focus or value to the company.

But Accenture research also finds that corporate leaders find it difficult to channel the entrepreneurial enthusiasm to the right areas with 85% reporting that employee ideas are mostly aimed at internal improvements rather than external ones.

Some of the problem is because managers may pose, “What do you think?” queries to workers without clearly defining what the problem is and what they're seeking in terms of innovative ideas, he says. If managers put up “guardrails” clearly defining their needs, workers would understand the limits and provide better solutions.

This agrees with my experience. Engineers are “kept in the dark” by building small pieces of functionality with prescriptive requirements. They can't see the big picture. I've seen cases where engineers who thought they had an innovative idea were ridiculed by the business side because the idea showed a naïve perspective of the market and customers. Some product managers designated as “the voice of the customer” jealously guard their special knowledge.

The Investment model defines a problem to solve for engineers. How can the software create product stakeholder value? Where are the opportunities for innovation where we can “knock a product stakeholder value out of the park?” Give a group of engineers a problem, and they will pour their energies into a solution. That's what they love to do, and what they were trained to do. They were reinforced for solving complicated problems every day in their engineering college curricula.

I know companies that try to increase innovation by teaching engineers problem‐solving skills. There's nothing wrong with learning good problem‐solving skills. They can be useful, but it's not the answer. Engineers know how to solve problems. It would be more effective to educate them on what their product stakeholders value.

After you have completed stakeholder value analysis, form a small innovation team comprising creative engineers and product managers. Ask them to identify values from key product stakeholders that provide opportunity for innovation – an “out‐of‐box” solution that will create a quantum leap in value. Consider having them go off‐site for a day or two with a facilitator skilled in brainstorming techniques like story boards. Let them run wild with the possibilities of new technologies. Their output can be a set of user scenarios that innovatively integrate new technologies. An Investment can then be defined to establish specific goals.

There is also a “simmer approach.” Create an internal innovation website open to anyone in the organization. Create discussion topics around stakeholder value. Anyone can contribute ideas and user scenarios to deliver significant stakeholder value. Someone will need to moderate the discussions and select those worthy of further review.

We still need the “culture of innovation” to create the motivation to contribute ideas. Adding comments or user scenarios to the website are behaviors. Discussion groups do have some level of positive reinforcement built in. Have you ever wondered why people contribute to discussion topics? They anticipate recognition for how smart they are. Innovation discussion groups leverage the strong engineering antecedent, “Tell me what you know.”

An intermediate approach is hosting periodic brainstorming sessions around a particular stakeholder or value. This could be hosted by an engineering leader, or a product manager. What a great way to demonstrate that your organization is serious about innovation!

Investments have the potential to increase innovation because they focus creativity on product stakeholder value. However, you can do all the above and find that there is little or no innovation. What is different about innovative organizations, and why is innovation advice not likely to work in your organization? For that, we need to turn to the behavior model of innovation.

14.3 Why Your Organization Can't Innovate

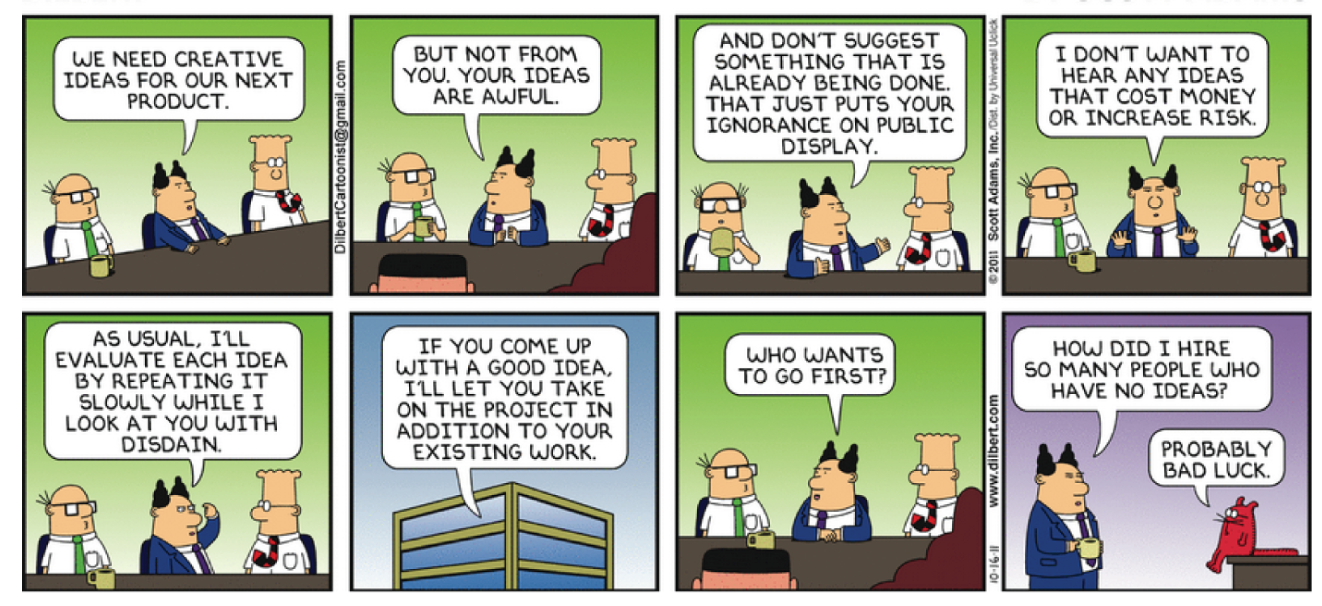

Source: DILBERT, 2011 Scott Adams, Inc. Used by permission of ANDREWS MCMEEL SYNDICATION.

I'll start with the same argument that was used to introduce the motivation topic. Do a web search on “secrets of innovation.” Again, pages and pages of “secrets” come up. If the secrets are out, why are so few companies innovative?

One clue is found by asking executives how often innovation is discussed in their weekly staff meetings. The answer is usually, “Not much.” What do they talk about? Problems and issues, like how to recover from a potentially late delivery or budget cuts.

My next question is, “Why would anyone in your organization think that innovation is important if you never talk about it?” I then ask executives what they actually do to support innovation. Typical answers are the following:

- We have posters on the wall that say that innovation is important.

- We have a great annual awards banquet where we honor the “Innovator of the Year.”

- We provide a $500 patent award.

- We have a suggestion box.

- We hand out little light bulb figures to put on people's desks to remind them of how important innovation is at our company.

- We encourage employees to spend 20% of their time on innovation like Google.

- We have objectives on performance reviews to submit at least one innovative idea each year (yes, I've seen that).

I then ask them if they consider themselves to be an innovative organization. The answer is “not really.” In fact, only a few large corporations are known for innovation. They are the 3Ms and the Apples of the world.

We'll see that organizations with strong cultures of innovation have been able to establish frequent positive reinforcement for the behaviors that lead to innovation. Innovation is a result of a series of behaviors that we can define, and innovative organizations have been able to reduce negative reinforcement that overrides any positive consequences for innovation. Innovation is a flickering flame that needs to be fanned with positive reinforcement, or it will die out.

Yes, we do see the “intrinsically motivated” innovators in our organization and should consider ourselves blessed to have them. The same question we asked of motivation applies, “What makes someone intrinsically motivated to pursue an innovation over a long period of time without positive reinforcement?” I preclude negative reinforcement because I don't think there are many examples of innovation under threat (we'll talk about Steve Jobs later). Innovation is a discretionary gift provided in anticipation of positive reinforcement.

I have studied the background of many famous inventors. I find they built up a history of positive reinforcement during childhood. There appears to be a common personality characteristic of extreme curiosity, but something happened to them along the way to make them pursue an invention, often with blood, sweat, and tears and many failures along the way. I typically see that they received positive reinforcement for behaviors that led to innovation when they were young.

Henry Ford is a good example. His parents let him put a workbench in their living room where he could tinker with and repair watches [2]. Can you imagine the recognition he would receive from his parents when he showed them a watch he had fixed, or something interesting he had discovered about watches? He received frequent positive reinforcement that resulted in intrinsic motivation to innovate with mechanical devices.

The conclusion is that organizations need to establish frequent positive reinforcement for behaviors that lead to innovation. Reinforcement that occurs only for the result of innovation is too far in the future to have any significant effect on day‐to‐day behaviors for most people. If you can increase these behaviors, innovation will happen in your organization. The first step is to identify behaviors that lead to innovation.

14.4 An Organizational Behavior Model of Innovation

I have observed that the following steps in Figure 14.1 are necessary to move innovation to the point where it gains support in an organization.

An individual needs to be aware of opportunities for innovation that will produce value to stakeholders and the company. The stakeholder value analysis discussed in Chapter 6 can provide the focus. An innovator in your organization needs to learn about what stakeholders value, as well as up and coming technologies that could be leveraged. If the information is out there but nobody takes the time and effort to learn it, nothing will happen.

Figure 14.1 The three steps of innovation.

Ideas for solutions need to be generated. We want to gather the ideas of multiple people. Linus Pauling, the Nobel Prize–winning chemist, is noted for his statement, “The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas and throw the bad ones away.” Volunteering an idea is a behavior. Encouraging and building on ideas are behaviors. And we want the ideas focused on product stakeholder value.

Nothing happens if we stop there. The idea must become a proposal to gain support. Creating and giving a demonstration are behaviors. For example, preparing a presentation for management to gain support is a behavior. It may start with a presentation to one's own manager.

As with motivation, there must be a system of positive consequences established for these innovation behaviors. A few “great ideas” tossed around or a patent award will not work. Certainly, a response of, “That's great, but we have a schedule to meet” is going to extinguish innovation behaviors. In fact, schedule pressure in engineering is the biggest factor in a company's inability to innovate. I have yet to see spontaneous innovation from an engineering group that is constantly under negative reinforcement for production.

It is possible to increase innovation in your organization where a limited level of schedule pressure exists. It's about offsetting any negative reinforcement to meet schedules with a higher degree of positive reinforcement for innovation behaviors. Practices to positively reinforce innovation behaviors are included at the end of this chapter. But first let's review the common practices in organizations today that “pay lip service” to innovation that have little impact.

Posters and Trinkets

- I have seen the most beautiful and eye‐catching posters along the halls in some organizations with captions like “Innovation is the lifeblood of our company.” Some just have the word “Innovate” and a light bulb. These general statements are unlikely to spur innovation. Recall that behaviors occur given anticipation of consequences. The behaviors leading to innovation will not happen unless people anticipate short‐term positive consequences. It's about what they experience, not about what you tell them is important.

- My favorite is when companies make statements about accepting or embracing failure. That's great until someone really fails. Did it really end up with gratitude for trying and what they learned? Likely not. It's unlikely that the innovator will have another chance to take a risk in that company. Besides, we have defined innovation as significantly increasing a product stakeholder value, not necessarily a revolutionary new product justifying substantial company Investment and risk. We want continuous innovation as part of the work people do.

Awards and Banquets

- Awards and ceremonies can become opportunities for recognition. They also demonstrate exemplary behavior in your organization and show that innovation does receive some attention. However, any consequences are usually far in the future and have no real impact on behaviors that lead to innovation. I doubt that anyone really innovates to attend an awards banquet.

- The other problem is that the award is given based on achieving innovation, not the steps that led to the innovation. Therefore, awards are given to those wonderful intrinsic innovators you may be lucky enough to have in your organization. You are motivating the self‐motivated. And, as with motivation, for every innovator you reward, there are 10 others disappointed because they didn't receive an award.

- Many companies use financial patent awards. I received several of them as an engineer in the telecommunications company for which I worked. The monetary award was never a factor in the innovation. I innovated because I loved to solve problems and to demonstrate how smart I was. I was a good problem solver, so I had built up a history of recognition for solving problems. I had become intrinsically motivated to solve tough problems.

- There was one impact of the patent award, however. It motivated me to go through all the boring paperwork and discussions with our patent attorney to complete the application. I guess the money was a bit of an incentive, but I mostly wanted the nice plaque that went along with it to hang on my wall to get recognition every time someone walked into my office. I wouldn't have admitted this to myself at the time.

Suggestion Box

- Don't waste your time. A suggestion box may yield some ideas for process improvement because people are knowledgeable of their own processes. However, most people don't know enough about their product stakeholders to innovate. The exceptions are companies where engineers are also stakeholders for the products they develop. Apple is an example where iPhone is used by engineers. Microsoft has been successful developing products used by engineers in their work. Visual Studio is a good example. SQL Server is another. Consumer products? Not so much.

- But the main reason suggestion boxes don't work is that any potential positive reinforcement is long delayed after the idea is submitted. Submitters may get form e‐mails like, “Thank you very much for your idea. Our selection committee meets at the end of each month and your idea will be considered. We will get back to you if your idea is selected for further discussion.” In either case, there is little or no recognition for submitting an idea. And, if there is, it is long delayed.

Dedicated Innovation Time

- This is one of the best examples of anecdote‐based innovation advice that is not likely to work in your organization. I've heard from engineering management who told people they should use a portion of their time to innovate, but few actually did. There's a simple answer. Any positive consequences for innovation behaviors are outweighed by near-team negative consequences in these organizations. I found that schedule pressure was the culprit. Nobody is going to spend 20% of their time on work that might lead to an innovation when they fear being called on the carpet for missing a schedule at the next project review meeting. And many of these companies set aggressive schedules to “motivate the team” to at least come close to an acceptable schedule, resulting in demotivated losers.

- Dedicated innovation time can work in a production‐oriented environment that uses negative reinforcement for motivation. Your only option is to take people out of their daily work environments and put them on an “Innovation team” with positive reinforcement for innovation behaviors. The downside is that you don't get innovation from everyone in your organization, and people removed from the development environment for long periods of time become stale in terms of their knowledge of technology and the software base. But if you can't address the negative consequences from schedule pressure, this is your only option.

Performance Reviews

- I have come across this several times. For example, “Submit an innovative idea each quarter that results in an improvement in our development process.” Setting innovation goals at least demonstrates that innovation is important. The bad news is that performance reviews don't have much impact on day‐to‐day performance.

- My wife Susan was a VP of HR at several high‐tech companies in the Seattle area. Performance reviews were considered a way to document poor performance to avoid legal issues after someone is fired (since then, HR has realized that performance reviews often have the opposite effect where nice managers have completed reviews with platitudes and acceptable performance ratings come back to bite them).

- HR people understand that the consequences for achieving performance review objectives are long delayed and therefore not very effective in improving day‐to‐day behavior. Exceeding your objectives might make the difference between a 2% and 3% salary increase. However, performance reviews are a way to communicate expectations.

- Susan explained that mandating performance reviews was the only way she could be sure that a manager sat down with an employee to give some feedback on performance at least once a quarter. That's why HR trains management to provide timely feedback. They understand that just setting objectives is not going to have much impact on day‐to‐day motivation. But face‐to‐face feedback is not a strength for most engineers, so it doesn't happen frequently.

14.4.1 An Innovation Tale of Two Companies

Consider two well‐known mobile phone manufacturers, one that out‐innovated the world, and one that fell from grace. The first is Apple. The second is Research in Motion (RIM), maker of the once-ubiquitous Blackberry phone.

Many people believe that Apple was innovative because Steve Jobs relentlessly drove people until they produced something he liked. Actually, Steve Jobs was proficient in applying consequences in his organization to foster innovation. He understood human behavior to the point where you may call him a manipulator. We've heard the stories of people being chewed out by Jobs. However, he also established a culture where positive reinforcement took place for behaviors that led to innovation.

The yelling and drama? Jobs understood that he could use negative reinforcement to encourage a behavior – stretching oneself beyond what they thought they could achieve. “Go back and try again.” However, innovation would not have thrived at Apple if the culture did not nurture innovation behaviors with frequent positive consequences. RIM will be our counter example.

Business Week posted an article on Apple's design processes in 2008 [3]. It included examples of how Apple used positive reinforcement for innovation behaviors. The article referred to Apple's paired design meetings:

This was really interesting. Every week, the teams have two meetings. One in which to brainstorm, to forget about constraints and think freely. As Lopp put it: to “go crazy.” Then they also hold a production meeting, an entirely separate but equally regular meeting which is the other's antithesis. Here, the designers and engineers are required to nail everything down, to work out how this crazy idea might actually work. This process and organization continue throughout the development of any app, though of course the balance shifts as the app progresses. But keeping an option for creative thought even at a late stage is really smart.

Apple recognized that ideas flourish in a positive environment. Criticism was left for a separate meeting where the practicality of the idea was assessed. Imagine the positive reinforcement in a meeting where engineers can be recognized for their ideas without fear of being shot down. I've been involved in brainstorming sessions where a card on the wall alternates between “creative” and “critical,” but the combination of positive and negative in the same meeting fails to build excitement in the room.

Innovation is reinforced at all levels at Apple. Here's an insight from the same Bloomberg Businessweek article on “Pony Meetings.”

This refers to a story Lopp told earlier in the session, in which he described the process of a senior manager outlining what they wanted from any new application: “I want WYSIWYG… I want it to support major browsers… I want it to reflect the spirit of the company.” Or, as Lopp put it: “I want a pony!” He added: “Who doesn't? A pony is gorgeous!” The problem, he said, is that these people are describing what they think they want. And even if they're misguided, they, as the ones signing the checks, really cannot be ignored.

The solution, he described, is to take the best ideas from the paired design meetings and present those to leadership, who might just decide that some of those ideas are, in fact, their longed‐for ponies. In this way, the ponies morph into deliverables. And the C‐suite, who are quite reasonable in wanting to know what designers are up to, and absolutely entitled to want to have a say in what's going on, are involved and included. And that helps to ensure that there are no nasty mistakes down the line.

Executives at the top positions of Apple take an interest in innovation. I believe these “Pony Meetings” would have been positive to foster innovation behaviors. Otherwise, they would have found that fewer and fewer engineers brought their ideas to them.

Take RIM as a counter example of positive reinforcement for innovation behaviors. A 2013 article in the Canadian news publication, The Globe and Mail, provided a synopsis of the rise and fall of RIM in the mobile phone industry [4].

In 2009, Fortune named RIM as the world's fastest growing company. Much of RIM's innovation is credited to an engineer named Mike Lazaridis, a founder of the company and company co‐CEO. Blackberry was a breakthrough technology at the time that incorporated a keyboard and LCD screen into a mobile phone. It was positioned as a mobile phone with e‐mail capability.

RIM executed a powerful marketing strategy. They focused initially on the business segment by providing company CFOs with a secure device that could be managed by their IT organizations. Blackberry then became one of the most popular consumer mobile phones. They continued to dominate the market after the initial breakthrough with incremental improvements in technology and design. It evolved from an e‐mail device to include web access via a custom browser, albeit buried within a maze of menus.

Then the iPhone happened. RIM sales plummeted. Their stock price dropped from $144.56 in June 2008 to $6.46 in September 2012. The company struggled along after introduction of the iPhone with forgettable “me-too” versions of their smartphone, but there was no innovation to differentiate themselves from the rest of the mobile phone manufacturers. Apple continued to out‐innovate them by quickly productizing leading‐edge technologies, like higher capacity memory chips and faster processers.

The Globe and Mail article provides evidence that RIM had a culture dominated by negative reinforcement. Larry Conlee was the RIM chief operating officer (COO).

The split company also lost a major unifying force when Chief Operating Officer Larry Conlee retired in 2009. Mr. Conlee was a whip‐cracker who held executives to account for decisions and deadlines, establishing a project management office. Many insiders agreed that after he left, a slack attitude toward hitting targets began to permeate the company. “There was a gap” after Mr. Conlee's departure, Adam Belsher, a former RIM vice‐president, told The Globe last year. “There was no real operational executive on the product side that would really get teams to hit deadlines.”

Note that once the pressure was removed, performance dropped in the company as described by “a slack attitude toward hitting targets.” This is a good example of the peril of operating on the negative reinforcement side of the motivation curve introduced in Chapter 13. Strong employee engagement didn't exist. When negative reinforcement was reduced, RIM moved toward the valley of the motivation curve.

It appears from the Globe and Mail article that the negative culture was established by co‐CEO Jim Balsillie, and Conlee was the enforcer. Some quotes from the article:

Mr. Balsillie was brash, competitive and athletic, and wore his reputation for being aggressive, even bullying in meetings, as a badge of honour. If anything, he viewed that outward toughness as a job requirement, not unlike tech CEOs such as Steve Ballmer at Microsoft Corp. or Apple's Steve Jobs. “Show me how else you build a $20‐billion company,” he once confided to a colleague. “If I was Mr. Easy‐going, they would kill BlackBerry.”

I'm not sure why he would use Ballmer as an example of a leader of innovation. And he obviously didn't understand the positive culture Jobs established to nurture innovation at Apple.

The behavior model of innovation would have predicted RIM's failure to innovate after their initial win based on a single idea from their cofounder, Mike Lazaridis. They failed to scale innovation by having a controlling culture and top‐down negative reinforcement.

There were other factors that made Apple successful. The smart marketing deal with AT&T. Betting on future technology advances, but there is a strong argument that these resulted from a strong sense of engagement and common goals throughout the organization.

14.4.2 Creating a Culture of Innovation

“Culture” is also one of those nebulous properties of organizations. As with innovation, I'll start with the dictionary. There are several definitions for “culture” in the Merriam‐Webster Dictionary, most relating to sociology. There is one definition relevant to corporations.

A set of shared attitudes, values, goals and practices that characterize an institution or organization.

I can support that. But what would you observe in an organization to know it has “shared attitudes and values?” It's based on the behaviors you would see if you were an observer in the organization. How do these behaviors come about and persist in organizations? That leads to my behavioral definition of culture.

Organizational culture is the set of behaviors that are frequently positively reinforced throughout the organization.

It doesn't matter what you claim your culture to be. It's based on behaviors people observe.

Organizational culture usually starts at the top with the CEO. The CEO establishes consequences for their executives, who do the same for their managers, who deliver consequences for their people. We can use RIM as an example, Balsillie as co‐CEO established the negative reinforcement culture. Conway, his COO, enforced the negative culture. I can't imagine a case of Conway receiving positive reinforcement from Balsillie because someone in the organization came up with a good idea, especially if schedules were being missed. A story from Conway about putting someone on the carpet or firing someone because of a late release would more likely have resulted in recognition from Balsillie.

Many of you reading this book are not CEOs so you may be disillusioned at this point because you don't control the top‐level culture of your organization. The good news is that you can build a culture of innovation within your scope of control if you can shield your team from negative reinforcement. This takes strong leadership. My definition of strong leadership is

A strong leader is willing to accept frequent negative consequences to support an environment of positive consequences for their team.

These are the engineering leaders who tell product management and their bosses that they are not going to apply pressure to their developers even though they themselves are under intense pressure. They will use positive reinforcement to increase motivation and innovation. How did they get there? These are leaders who have built a history of success.

14.4.2.1 Learning about Opportunities for Innovation

This is the first step in the innovation model. People need to understand opportunities for significantly increasing stakeholder value. I don't limit this to “product stakeholder value” because we also want innovation for internal processes that significantly increase a value for internal stakeholders. For example, a developer might create a “nonobvious” class library that reduces development effort of their department by 50%.

As a leader, you need to create the opportunities and provide the time and priority to learn about stakeholders. Some examples:

- Periodic team meetings with a product manager who leads the discussion on a specific stakeholder value followed by brainstorming of ideas or user scenarios.

- Ask for volunteers to follow new technologies they are interested in that may be applicable to your product, solution, or process. Take a portion of the weekly staff meeting for technology update presentations where they can receive recognition for their research. If you don't get volunteers, you haven't created the positive reinforcement.

- Send engineers to customer sites to shadow users of your application. Give them an opportunity to present to the department when they return.

Note that the positive reinforcement occurs during or soon after the desired behaviors in the examples above. I'm sure you can think of other ways to do this in your organization.

You first reaction may be “OMG, this is going to take some time away from production.” If this is your reaction, don't bother trying these methods. Accept that you are a product organization where innovation is not a high priority. There's nothing wrong with that. Just set the expectations of the people who work for you, but accept that innovation posters and trinkets are not going to change anything.

There is another important point to be made here that also applies to the idea generation and proposal stages. We know that managers must establish the environment for frequent positive reinforcement. This involves behaviors on the part of a manager. Therefore, managers must receive positive reinforcement for behaviors that create the environment in which positive reinforcement for innovation behaviors takes place. In other words, if you want your manager to find ways to motivate their teams to innovate, the manager needs to be positively reinforced for implementing systems of positive reinforcement for innovation.

Managers may receive some recognition from their teams for supporting innovation, but there also needs to be positive reinforcement from their managers. This applies all the way up to leaders at any level. At some point, you are likely to reach a high management level where negative reinforcement prevails. This requires strong leadership to overcome, as we defined it.

One simple approach is to use at least 15 minutes of your staff meeting for open discussion on what your management team has done this week to build an environment of positive reinforcement for innovation behaviors, or how they have done something to reduce negative consequences that may override the positive consequences. For example, a manager may have asked a product manager to attend a team meeting to improve insight on product stakeholder value, or perhaps they even invited a real customer.

Don't go around the table and ask each manager to report what they've done. This feels like typical status reporting used for negative reinforcement. Just open the discussion, “What have we done this week to establish positive recognition for innovation?” No volunteers at first? Give it a chance. If still nothing, you may give them a serious talk to remind them of the importance you place on innovation. Perhaps give examples where you have promoted innovation. Eventually, a flame will flicker that can be fanned with positive reinforcement.

You have a manager who never contributes? Have an individual discussion with them to find out why and to stress that you consider this to be a major part of their job responsibilities. As soon as you observe a hint of the desired behavior, move to positive reinforcement.

If you are at the director or VP level, you may experience even more angst at the thought of having to dedicate precious time to innovation instead of more “important things.” If so, you're not ready to try this. Innovation is actually not a priority for you.

14.4.2.2 Generating Ideas

This one shouldn't be difficult because most engineers like to contribute ideas. Remember “Tell me what you know” from the motivation chapter. Again, it's just a matter of leadership providing the opportunity for positive reinforcement for ideas focused on stakeholder values.

Create an internal collaboration site organized by product stakeholders. Include their values as topics and encourage engineers to submit innovative ideas. Engineers will provide positive comments for ideas if positive reinforcement dominates in your organization. You can also schedule meetings with people who can contribute ideas to a specific stakeholder value. Use separate creative and critical meetings as Apple does.

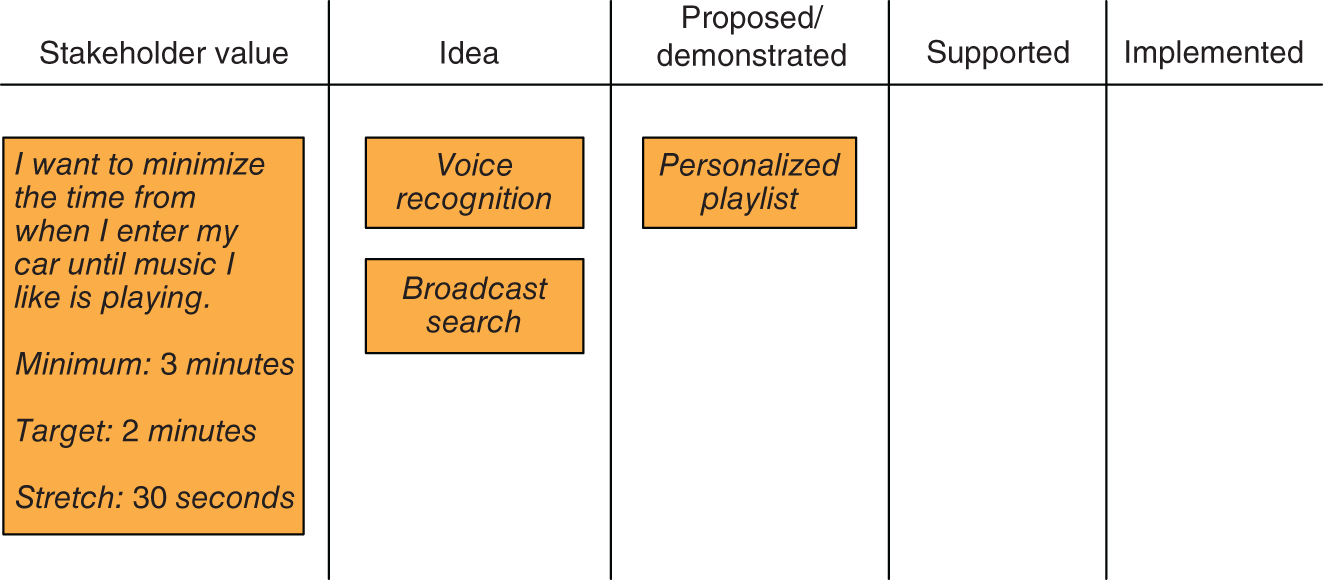

Figure 14.2 Innovation Kanban board.

At some point, the ideas need to be filtered to determine which should be submitted to the next level of management to garner support. My recommendation is a physical innovation Kanban board at each level in the organization like the example in Figure 14.2.

A first‐level manager facilitates updates to their team's board each week. Again, no status reporting. People volunteer ideas and update progress in anticipation of positive reinforcement. Why would the manager be motivated to maintain the board? Because he or she gets to volunteer success stories at their manager's weekly innovation discussion. They also could pitch for support from their next level of management if implementation is beyond their control. For example, it may require departmental funding. Once support is gained at the next level, they can move the idea to the “Supported” column, with positive reinforcement from their team and boss.

The ideas supported by the next management level appear on their Kanban boards. Their boards show the progress of innovations that have reached their level of support. The board is reviewed weekly at each management staff meeting, with recognition for helping move a card across the board. What message do you think that sends about the importance management assigns to innovation? You're no longer just paying lip service to innovation.

If you are an engineer, you're probably already thinking about how the Kanban can be implemented in a relational database. Don't do it. You now know that the social interaction surrounding changes in Kanban card positions provides the opportunities for positive reinforcement. I guess you could put the Kanban online and update it from a video screen during the meeting, but I don't think that results in the same team recognition as the physical cards. Moving a card is a ceremony. Better yet, post all the Kanban boards along a wall that everyone passes. What a strong message it sends to see a VP updating the board with an enthusiastic group of directors! You can see in the survey in Appendix E that one of the most significant questions that determines the level of innovation is, “My department encourages and supports good ideas.”

Think of other ways to communicate and recognize innovation at the department level. Start “tweeting” on innovation and recognize good things that happened that day or week. Recognize your managers in the tweets for what they have done to contribute to innovation in the department. The innovation itself is not the basis for reinforcement. It is the behaviors of your managers that created the environment from which innovation was born. Always ask them what they did to make the innovation happen. It's an opportunity for reinforcement as well as to share effective methods among your managers.

Go ahead and invite an innovator to a higher‐level staff meeting to present their idea to receive positive reinforcement. It can be an effective reinforcer if the presenter perceives it as a positive meeting. However, I would argue that the same meeting would be better spent having a manager present on how they established the environment that led to the innovation. You will only reinforce a single innovator in the meeting. Reinforce the manager for the environment they have created, and this will motivate multiple potential innovators.

14.4.2.3 Innovation Proposals and Demonstrations

This is the final step before implementation for many innovations. Many good ideas are within the control of the individual or manager, and it only takes a “let's do it!” Others may require significant commitments of resources and money. Creating a proposal may involve negative consequences for those who must take the time away from their work or something else they enjoy. You need to establish the opportunities for reinforcement for creating and pitching the proposal.

Hackathons are excellent vehicles for innovation reinforcement. There is excitement in the room as engineers huddle around a workstation to recognize something cool. It generates peer recognition from “show me what you built.” Try to do one each month. Walk around and select a few near the end of the session for presentation to the entire group.

Establish innovation demonstration stations in well‐traveled areas. It doesn't have to just be engineers. Catch product managers or operations people on their way to lunch. Engineers will thrive with positive feedback for their demonstrations.

Give someone a week off to create a presentation or demonstration. You say you are serious about innovation? Show it.

I'll end this chapter with the same subject discussed at the end of the motivation in Chapter 13. Does working from home impact innovation? I've seen many articles that acknowledge the possibility of losing spontaneous ideas from incidental contact in the workplace. The behavior model of innovation shows that these articles miss the real impact to innovation – the environment of positive reinforcement for behaviors that lead to motivation. It is possible to recreate some of the innovation reinforcement methods over video, but they limit opportunities for reinforcement to scheduled meetings.

The sad truth is that most companies will not see a decrease in innovation because they have been unable to create that nebulous, “culture of innovation” in the first place. Refer to the preceding motivation chapter about working from home. You will need to schedule weekly video meetings where people can be reinforced by their peers for innovation.

It should now be clear now why so few organizations are innovative. It takes more than innovation posters or great award dinners. It takes the full commitment from management to stoke innovation behaviors every week. This level of commitment must come from the top. Most engineering organizations are driven by pressure that starts at the CEO level. Executives spend virtually none of their time supporting innovation.

Of course, business schedule and financial commitments must be met. However, find a way to apply positive consequences for both production and innovation. Investments are a good start to get innovation flowing because they provide your engineers with problems to solve. Address behaviors that lead to innovation with positive reinforcement to create the culture that produces innovative products.

14.5 Summary

- An Investment facilitates innovation by providing engineers with the problem to solve.

- Involving engineers in Investment planning gives them an opportunity to innovate.

- Innovation is a nonobvious improvement provided by a product, process, or solution that results in a notable increase in product stakeholder value.

- Innovation is a result of a series of behaviors.

- Culture is defined by the behaviors observed in your organization.

- Innovation can be increased through effective positive reinforcement of behaviors that lead to innovation.

- Many companies apply ineffective methods to increase innovation because they lack near‐term positive consequences for behaviors that lead to innovation.

- Schedule pressure is the antithesis of innovation.

- There are three phases of corporate innovation

- ○ Identifying stakeholder value

- ○ Generating ideas

- ○ Creating proposals

- Near‐term positive consequences can be established for behaviors that support the innovation phases.

- Innovative organizations balance production and innovation through positive reinforcement.

References

- 1 US Government (2014). Is America losing its innovation edge? USA Today (5 January).

- 2 Curcio, V. (2013). Henry Ford. Oxford University Press.

- 3 Apples design process. Bloomberg Businessweek (March 8 2008).

- 4 Sean Silcoff, Jacquie McNish and Steve Ladurantaye (2013). Inside the fall of Blackberry. The Globe and Mail (27 September).

Note

- 1 35 U.S. Code §103 – Conditions for patentability; nonobvious subject matter.