Chapter 18

Initiating Innovation

In This Chapter

![]() Seeing how innovation crowdsourcing works

Seeing how innovation crowdsourcing works

![]() Innovating for new and improved ideas, and for advancement

Innovating for new and improved ideas, and for advancement

![]() Laying the foundations for innovation

Laying the foundations for innovation

![]() Getting the best from the crowd

Getting the best from the crowd

![]() Co-creating products

Co-creating products

Innovation is an important part of any organisation. If an organisation doesn’t renew itself with fresh ideas and new perspectives, it stagnates and dies. Innovation gives an organisation the ability to deal with the problems of a changing world.

Many individuals confuse innovation with invention. However, innovation isn’t the same thing as invention. Invention is the process of creating a new idea, a new product or a new activity. Innovation is the process of getting a new view of your circumstances. Invention is one form of innovation, but it’s not the only form. You’re innovative whenever you:

![]() Realise that something’s more important than you used to believe

Realise that something’s more important than you used to believe

![]() Discover that you can fix a problem in an office simply by rearranging the way that the workers interact with each other

Discover that you can fix a problem in an office simply by rearranging the way that the workers interact with each other

![]() Appreciate that your market’s been telling you what it wants

Appreciate that your market’s been telling you what it wants

![]() Identify a new use for an existing product

Identify a new use for an existing product

![]() Uncover a way of avoiding certain mistakes

Uncover a way of avoiding certain mistakes

![]() Find a way of being more efficient

Find a way of being more efficient

You can innovate all by yourself, but you often find it easiest to innovate when you work with others who have skills, experience and points of view that are different from your own. Many organisations create diverse innovation teams to develop new ideas. So to develop ways of improving its services, a company may assemble a team that consists of a manager, an engineer, a marketing director, a member of the financial office, a sales person and perhaps someone from the human resources staff. The company anticipates that the combined abilities of these individuals can better understand the problem than any one individual can, and the team is better able to identify an innovative solution. And if innovation looks to gather ideas from a diverse collection of people and identify new and practical ideas, then it’s an ideal activity to crowdsource.

In this chapter, I look at how to get new ideas from the crowd, how crowd innovation is something more than holding a popularity contest on the web, and how you can build a market for your ideas by having the crowd help with your innovation.

Understanding the Forms of Innovation Crowdsourcing

The crowd can be far more diverse than any committee that you may assemble within your organisation, and it often has expertise that you can get in no other way. Your customers often understand your products better than the engineers who designed them do. Your employees often understand the operations of your organisation better than any managers do. Complete strangers can give you expertise that you’ll never find within your organisation.

Innovation crowdsourcing attempts to answer questions by engaging the collective intelligence of the crowd. Except in the most extreme circumstances, a crowd of people, collectively, has a broader intelligence than any one person. The crowd has greater experience and contains more diverse points of view than a single individual. Therefore, if you put a question to a crowd, you may receive an answer that’s far more useful than one you’d get from a single expert.

![]() Closed innovation looks to a group of known experts to generate and evaluate ideas.

Closed innovation looks to a group of known experts to generate and evaluate ideas.

![]() Open innovation looks to a much larger class of people to be involved in the work. These people may not have been involved with the organisation before or even know of its activities.

Open innovation looks to a much larger class of people to be involved in the work. These people may not have been involved with the organisation before or even know of its activities.

In general, crowdsourced innovation is considered to be a form of open innovation, although in some cases it can be a form of closed innovation as well. As with all forms of crowdsourcing, innovation crowdsourcing utilises markets to combine the ideas of the crowd. The crowdmarket will help you understand how the crowd values different ideas.

You can use two types of crowdsourcing to drive innovation:

![]() Crowdcontest: In the simplest form of crowdcontest, you put a question to the crowd and offer a prize for the best answer. That prize can be a monetary reward, publicity for a good idea, a stake in your corporation or even the opportunity to turn the winner’s idea into a real product or service. After you’ve announced the contest, you wait for submissions, evaluate the ideas, and reward the one that seems to be the best answer to your question. (For more on crowdcontests, head over to Chapter 5.)

Crowdcontest: In the simplest form of crowdcontest, you put a question to the crowd and offer a prize for the best answer. That prize can be a monetary reward, publicity for a good idea, a stake in your corporation or even the opportunity to turn the winner’s idea into a real product or service. After you’ve announced the contest, you wait for submissions, evaluate the ideas, and reward the one that seems to be the best answer to your question. (For more on crowdcontests, head over to Chapter 5.)

The crowdcontest form of innovation crowdsourcing can also be seen as a form of market research. Through a crowdcontest, you try to understand how a group of people understand your question and, from that understanding, extract a good answer. Like market research, an innovation crowdcontest can involve much more than a simple contest. You can engage the crowd members in a discussion to help them refine their ideas. You can encourage the crowd to talk to itself in order to generate as many ideas as possible. You can utilise the crowd to evaluate ideas and tell you how they can best answer your question. You can get information that you can’t out of a survey or questionnaire, because you can uncover ideas that you didn’t expect.

![]() Macrotasking: You can also consider innovation crowdsourcing to be a form of macrotasking, of engaging outside expertise. In this form of crowdsourcing, you recognise that you need a solution to a specific problem, and you identify the kind of expertise that you may need to address that problem. You then ask the appropriate experts to propose answers to those questions. Using this form of innovation crowdsourcing, organisations have developed new algorithms, created new chemical compounds, and discovered ways of removing environmental threats. (For more on macrotasking, see Chapter 7 and the nearby sidebar, Finding better ways of storing energy.)

Macrotasking: You can also consider innovation crowdsourcing to be a form of macrotasking, of engaging outside expertise. In this form of crowdsourcing, you recognise that you need a solution to a specific problem, and you identify the kind of expertise that you may need to address that problem. You then ask the appropriate experts to propose answers to those questions. Using this form of innovation crowdsourcing, organisations have developed new algorithms, created new chemical compounds, and discovered ways of removing environmental threats. (For more on macrotasking, see Chapter 7 and the nearby sidebar, Finding better ways of storing energy.)

Asking for a Little Insight: Classes of Innovation

Innovation can be something much more than invention. Invention creates a new product, service or idea, but innovation creates a new way of looking at your organisation, your activities, your ideas. Inventions can create new ways of looking at the world, but many are simple improvements that do little to change your point of view. Often, real innovation comes from finding out that a certain idea is more important than you previously thought, or that a particular concept is really worth all the attention you’ve been giving it.

Innovation divides into three different classes of idea. You can find innovations that:

![]() Discover new ideas

Discover new ideas

![]() Suggest substantial improvements over old ideas

Suggest substantial improvements over old ideas

![]() Create a true advantage or altered world view

Create a true advantage or altered world view

Before you start innovation crowdsourcing, you need to determine the kind of idea you want to find. Each class of innovation requires its own approach to crowdsourcing.

Crowdsourcing for novelty

When you crowdsource for novelty, you look for something that’s truly new. The new idea may offer no real advantage other than a changed package or a slight alteration that breaks people out of their old habits. However, you look for something that’s not been seen before. You rely on the crowd to tell you that the innovative idea hasn’t been seen before in this setting.

Although novel ideas may not change the fundamental way in which you think, they still have value. Many a company’s been able to reposition a product and gain market share by redesigning the box and then advertising its ‘new, improved packaging’.

Even some of the simplest novel ideas can spark innovation that proves to be important. Organisations have often discovered that big changes came to the way they operated when they adopted small changes merely for the sake of novelty. They processed applications in reverse alphabetical order, for example, or reorganised the columns of a spreadsheet that was important to their operations.

Crowdsourcing for improvement

Crowdsourcing for improvement is a common form of crowd innovation. You consider an idea and try to fix it, improve it with established criteria, or utilise it in a new way. Often, you look for only minor modifications, although you have to be prepared for suggestions that can produce radical changes. The crowd may see an entirely new market for a product or suggest how to completely restructure some activity.

By looking for improvement, you generally have clear, concrete goals for your innovation. You can provide concrete measures that you can use to judge the improvement of the evolving ideas.

Crowdsourcing for advantage

In looking for an innovative advantage, you seek to improve or restructure a product or service substantially. You want that new idea to be a thorough improvement over its predecessor, but you place few or no restrictions on the changes you’re seeking. You ask primarily that the new ideas create an advantage by being cheaper, generating more revenue, being easier to operate, or opening an entirely new market.

Often, crowdsourcing for advantage looks to engage untapped expertise. Usually, you’re not trying to create a new product or make radical changes to a service. You’re trying to find a more advantageous position for your goods or services in the market.

In crowdsourcing for advantage, Kimberly-Clark puts out a request to the crowd, which consists of mothers or others who have experience with young children. The company asks the crowd to submit ideas for products and ‘businesses that nurture the relationship between mother and child’. Each member of the crowd has to submit a simplified business plan for the product or business. Kimberly-Clark then employs a panel of experts to judge each application according to four criteria:

![]() Originality and creativity

Originality and creativity

![]() Ability to solve a problem important to parents

Ability to solve a problem important to parents

![]() Commercial viability

Commercial viability

![]() Stage of business development

Stage of business development

Typically, the company gives the mothers with the best ideas a grant to help start or develop a business. Some of the top ideas are brought into the Kimberly-Clark company and used to expand the company’s line of baby products.

Planning for Innovation

Planning to innovate is almost a self-contradictory idea. You tell yourself that you’ll have a new idea at a certain time, in a certain place and under certain circumstances. Innovation, though, is closer to inspiration, which comes in its own time and on its own terms. Innovation is not like being able to think of an impossible thing each morning before breakfast, as the Red Queen in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland claimed she could do. Indeed, you can’t force inspiration and you can’t dictate innovation to arrive on schedule, as a large literature on the subject suggests. Still, you need innovative ideas in order to progress and, if you’re offering goods or services in a market, you need to make plans for yourself and your organisation. In such a world, unplanned innovation is too haphazard to trust.

Planned innovation is further complicated by the fact that you’re usually constrained by your own actions, your history, your community, your market or your customers. You can’t simply put out a call and ask, ‘Teach us to think in new ways or do new things.’ You have to fit your new ideas into your existing world.

The following sections help you pin down which aspects of crowdsourcing innovation you can plan, and how.

Planning for new ideas

All innovation needs new ideas, so when you start to plan for innovation, you need to start by determining how you’ll get new ideas.

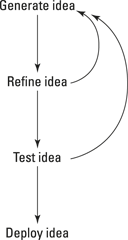

In planned innovation, with or without crowds, you generally move through a series of steps that seem far more orderly on paper than they are in practice. In these steps, you generate ideas, refine ideas, test the ideas and finally deploy the ideas. You rarely follow these steps in a linear order. Instead, you move in circles, cycling among them as you see that a particular combination of skill, experience, insight and occasional serendipity produces a valid, usable new idea. The basic process is shown in the diagram in Figure 18-1. These four steps are sometimes called the process of ideation.

Figure 18-1: The steps of generating new ideas.

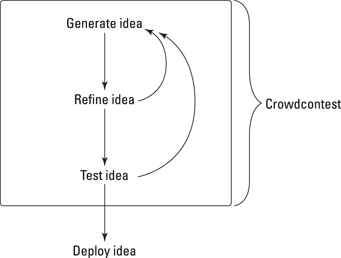

To use crowdsourcing to create and gather new ideas, you put the first three steps of the idea-generating process into a crowdcontest. You use that contest to generate, develop and test new ideas. Figure 18-2 shows the role of the crowdcontest (for more on crowdcontests, take a look at Chapter 5).

Figure 18-2: Generating ideas with crowd-contests.

Bringing the unexpected into your plan with a crowdcontest

If you need to create new ideas that satisfy the deadline of your plan, you can always try a crowdcontest. Crowdcontests don’t really create new ideas according to plan, but they do pull new ideas out of the crowd to a deadline. If you think that the crowd has a new idea, you can easily use a simple crowdcontest to innovate:

1. Describe the kind of innovation you’re seeking.

2. Offer a reward for the best idea.

3. Establish a deadline for the contest.

4. Promote the contest to the crowd.

5. Collect the results.

6. Select the best idea.

7. Implement the result.

Rather than look for a specialised crowdmarket that handles innovation, you can run this contest on your organisation’s web page. You create the page, notify the crowd and get the process started.

Defining the problem

When you begin to plan for innovation crowdsourcing, you need to describe the idea that you’re seeking: the novelty you hope to create, the improvement you need, the advantage you hope to establish. This step is similar to drafting a statement of work in macrotasking or microtasking (see Chapter 11). However, unlike the problem of defining a job for those forms of crowdsourcing or describing a product in an ordinary crowdcontest, this task can be daunting. Your goal isn’t always obvious. You may understand the need for innovation, but you may not see all the possible solutions.

You can have a simple crowdcontest if you can clearly describe your problem at the start. Remember that you’ve been involved in this innovation process longer than any of the crowd have, and hence you may have ideas and you may have made assumptions that aren’t obvious to the crowd. Start by describing the problem as best you can. Be as concrete as you can but leave enough freedom for the crowd to be creative. You want to let the crowd members’ intelligence, experience and expertise lead you to a useful set of ideas.

If your problem is complex or if you can’t clearly anticipate the kinds of ideas you need, allow yourself the option of revising the statement of the problem. You have a choice of two easy ways of doing this:

![]() Update your problem description during the course of the contest. You follow the cycle back to the start of the innovation process illustrated in Figure 18-1. Updating the problem description has some obvious drawbacks. In some cases, members of the crowd may take offence and object to your changes. However, if you tell the crowd that you’ll be engaged in a dialogue with them and will help them refine their ideas, you’re more likely to get a positive response.

Update your problem description during the course of the contest. You follow the cycle back to the start of the innovation process illustrated in Figure 18-1. Updating the problem description has some obvious drawbacks. In some cases, members of the crowd may take offence and object to your changes. However, if you tell the crowd that you’ll be engaged in a dialogue with them and will help them refine their ideas, you’re more likely to get a positive response.

You can establish the contest so that you update the project description on a regular basis, whether you make any real changes or not. If you have no real updates, you can report on the state of the contest. You can tell the crowd about the number of submissions or general nature of the submissions and the ideas that may work. By making these statements, you emphasise that innovation crowdsourcing is indeed a dialogue with the crowd.

You can establish the contest so that you update the project description on a regular basis, whether you make any real changes or not. If you have no real updates, you can report on the state of the contest. You can tell the crowd about the number of submissions or general nature of the submissions and the ideas that may work. By making these statements, you emphasise that innovation crowdsourcing is indeed a dialogue with the crowd.

![]() Run your innovation crowdsourcing as a two-stage contest. As with an ordinary crowdcontest, you identify the most promising ideas in the first stage, give the creators of those ideas a modest award, and then allow those creators to participate in a second stage to refine their ideas.

Run your innovation crowdsourcing as a two-stage contest. As with an ordinary crowdcontest, you identify the most promising ideas in the first stage, give the creators of those ideas a modest award, and then allow those creators to participate in a second stage to refine their ideas.

When you start the second stage, you can give feedback to the participants, refine your problem description or even encourage the participants to collaborate. The Netflix contest (see the earlier section Crowdsourcing for improvement) is a good example of a two-stage contest. In the second stage, Netflix not only refined its instructions and gave feedback to the crowd, but it encouraged certain teams to collaborate and submit a single entry.

Refining the ideas

In planned innovation, you often want to encourage the crowd to refine its ideas. This refining is part of the dialogue with the crowd. The crowd members read your description and offer responses. When you see the responses, you better understand how the crowd members perceive your problem. In the process, you may realise that they didn’t fully understand your description of the problem, or that they saw aspects of your problem that you hadn’t anticipated. Therefore, the process of innovation works best if you communicate with the crowd and help to refine the ideas.

Much of the communication with the crowd is like the feedback in ordinary crowdcontests (see Chapter 5). You correspond with individual members. You tell them that you like a certain aspect of their work but not another, or suggest that they may not understand the problem, or that their work is promising and should be extended in a certain way. You usually conduct such correspondence in a private manner so that each of your suggestions is seen only by specific members of the crowd.

However, you can use the crowd itself to refine ideas. In this model, you post all the submissions on public pages and let the crowd comment on them. The owners of those ideas can read the comments and make new submissions that incorporate the feedback from the crowd.

Testing the concept

In innovation crowdsourcing, you have to test the best ideas to see whether they actually work. To do this, you may choose to divide the evaluation process into two parts:

1. A panel of judges reviews each entry and selects the idea (or ideas) that seems the most promising.

The people who generated these ideas then receive part of the payment that you’re offering for the crowdcontest.

2. You try to use the chosen ideas.

If you’re trying to create a novel marketing plan, you use the idea to create such a plan and then try to follow it. If you’re trying to fix a process, you try to apply the idea and observe the result. If you’re trying to create a new product with the idea, you manufacture the product and try to market it. You give a full payment to the winning idea only if it works.

Integrating the idea into the organisation

After you select an innovative idea, you have to integrate it into your organisation. As with any organisational change, you’ll find this step easiest if you’ve prepared your organisation and given it a stake in the process. If the organisation isn’t ready to accept a new idea, it can easily thwart any innovation.

You can easily include your organisation in the work that defines the crowdcontest and judges the submissions. Your employees may be in the best position to understand the kind of innovation you need and judge the kind of results you want.

However, you may want to change your organisation, to develop a new product or service that’s quite different from the work that the group’s currently doing. In such a case, you may want to define the crowdcontest by yourself and create a panel of judges that’s independent of the organisation. By excluding your organisation from this work, you can demand fresh ideas and fresh points of view.

Running with the Right Crowd

As with all forms of crowdsourcing, innovation crowdsourcing demands that you have a crowd that’s well matched for the innovation that you’re trying to develop. If someone in the crowd doesn’t have the right experience, right skills or right connections to the problem, you get nothing of value from her.

The problem of finding the right crowd is much like a similar problem in market research. In market research, you try to understand the preferences and inclinations of your customers by assembling a small group of people who represent your customers. You try to ensure that your small group has the same preferences and inclinations by using methods that are statistical selection techniques.

In innovation crowdsourcing, you try to get skills and ideas that come from a known body of people such as your employees or customers. Unlike market research, you rarely need to have a crowd that perfectly represents these groups of people. If anything, you want to have the best customers or most insightful employees in your crowd.

Knowing the different types of crowd

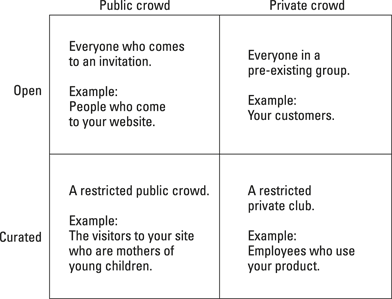

In innovation crowdsourcing, you can use two classes of crowd:

![]() Public crowds are recruited through a public invitation. They may be built out of people who come to your website.

Public crowds are recruited through a public invitation. They may be built out of people who come to your website.

![]() Private crowds begin with a group of people that you already know. They may be assembled from your employees, customers or members.

Private crowds begin with a group of people that you already know. They may be assembled from your employees, customers or members.

Both kinds of crowd can be further divided into two classes:

![]() In open crowds, you take everyone who comes as a member of your crowd.

In open crowds, you take everyone who comes as a member of your crowd.

![]() In curated crowds, you restrict membership to people who have specific experience, skills or positions.

In curated crowds, you restrict membership to people who have specific experience, skills or positions.

Figure 18-3 shows the different types of crowd and gives an example for each.

Figure 18-3: Different types of crowds for innovation.

Matching your plans with the best crowd

You can use the same kind of crowd to crowdsource for any kind of crowdsourced innovation: novelty, improvement or advantage (see the earlier section Asking for a Little Insight: Classes of Innovation). However, each of the three categories of innovation requires a slightly different approach, as the following sections outline.

![]() The crowd has the ability to provide you with good ideas.

The crowd has the ability to provide you with good ideas.

![]() The crowd isn’t committed to your current products, services and procedures. If the crowd members think that everything you do is fine and good, they won’t be able to give you a fresh vision.

The crowd isn’t committed to your current products, services and procedures. If the crowd members think that everything you do is fine and good, they won’t be able to give you a fresh vision.

Crowds for novelty

In crowdsourcing for novelty, you generally try to determine how a group of people perceive an idea and what they would need to perceive it as new. You want to find the crowd that’s in a position to identify novelty and can communicate that novelty to other groups. Often, you start with a private crowd, a crowd that understands the way your organisation currently operates or the ideas it promotes. You probably restrict the crowd to a group with specific skills.

However, if you hope to change your organisation radically, perhaps move into a new area of activity, you may want a crowd that knows a little about your organisation. In this case, you probably want a curated public crowd. You invite a large group of people to join your crowd and then restrict yourself to a group who understand what you’re trying to do. You restrict the group by asking each potential member a set of questions, and you take only those who answer in the way that you want.

Crowds for improvement

When you crowdsource for improvement, you generally try to find a solution to a concrete problem. Your product isn’t working as planned and you need a solution. Perhaps your website seems to be functioning well but 70 per cent of the visitors spend more than five minutes on the site and don’t find the information they need; or your main service seems to be working well in the English language market, but you want to expand it to the Spanish market.

In this form of crowd innovation, you look for a specific set of skills or experience. Often, you find it easy to use the open private crowd of your employees and the one of your customers. Crowdsourcing for improvement is a means of utilising expertise that’s often difficult to engage. It utilises the things that your customers have discovered about your products and that your employees know about your business processes.

You can deal with specific problems or general questions that look for any kind of improvement. However, in both cases, you need to guide the crowd or you get answers that are of little use. If you merely ask ‘How can we improve this process?’ you’re likely to get odd opinions that offer little real insight.

We are attempting to improve our website to make it more useful to our clients. We would like your ideas that may address one or all these questions:

• What general change would improve the website?

• How would you change the opening page and the first impression of the site?

• What can be done to improve the navigation between pages?

• How can we best display the products on the shopping page?

Crowds for advancement

Crowdsourcing for advancement is the most sophisticated form of innovation crowdsourcing and often demands a crowd that’s been chosen with care. The crowd needs to be able to address open-ended questions and to have enough distance from your current products or approach to operations not to be trapped in old ideas.

Commonly, you crowdsource for advancement with a curated public crowd. You invite a large group of people to join the crowd and then select those who are the most prepared. However, you can successfully use private crowds, such as a crowd drawn from your employees.

Communicating effectively with the crowd

In innovation crowdsourcing, you need to ask your questions in a way that your crowd not only understands but can also answer.

Opinions and indications of popularity have a place in innovation crowdsourcing, but they’re not the only input you need. It may be useful to know that someone agrees with you or that the crowd believes that it’ll benefit from a certain idea. However, you’re likely to want stronger evidence that an idea’s good and can solve your problem. You may also want concrete reasons that show how one idea is superior to another. You may want a story that shows how a proposed idea has worked in other settings. You may want an explanation of how an idea can improve your organisation. Such reasons, stories or explanations come from opinions or popularity polls.

However, if you broaden the question that you put to the crowd and ask for an explanation, you’re likely to get much more useful answers. The two-part question: ‘What should the city do to improve the quality of life in your neighbourhood?’ and ‘What problem would the improvement address?’ is far more likely to get responses that move beyond limited opinions and personal needs.

Building New Products and Services with Co-creation

Co-creation is a form of innovation crowdsourcing that develops new products and services. You use the crowd to identify new ideas, define a potential product, design that product, test the product, and release that product. Many commentators describe co-creation as a form of new product development that uses a market to create products for itself, but it’s actually a much broader activity. Co-creation uses the skills and experience of a crowd to create fully formed products and bring them to market. Often, that crowd may be creating products for its own use; however, it can also create products for other markets.

In the artistic world, the term co-creation has come to mean an artistic project that involves multiple people who coordinate their activities over the Internet. In this arena, an individual conceives a project and solicits submissions. The creator then chooses the best submissions and combines them into a new artistic work.

In some areas of business, the concept of co-creation is merely another form of design contest. The European site eYeka (http://en.eyeka.com) portrays itself as a co-creation site. It runs crowdcontests to develop packages, adverts, videos and logos for existing products and brands.

When you use co-creation to develop a new product, you do far more work than when you merely create an advert or logo. You typically go through five different steps:

1. Generate new ideas.

2. Define the product.

3. Design the prototype.

4. Test the prototype.

5. Release the product to the market.

Each of these steps can be done as a crowdcontest or as a macrotask.

Generating ideas and defining products

When co-creating as a form of crowd innovation, you usually combine the first two steps into a single process. You generally identify an area or field in which you’d like to develop a product. You don’t need the crowd to identify that field, although you may easily ask it to do so. Instead, you state the area that you want to develop and ask for ideas that will make good products. This activity can easily be done as a crowdcontest and is really a form of crowdsourcing innovation for advancement, similar to what Kimberly-Clark is doing to develop new products with the expertise of mothers (see the earlier section Crowdsourcing for advantage).

Designing with the crowd

After you have an idea for a product, you can easily create another crowdcontest to design it. If the product is simple, you can do your crowdsourcing as a simple contest in which you look for the best work of a single designer. If it’s a complicated product, you’ll oversee a self-organised crowd. In this kind of crowdsourcing, you place a description of the product on the crowdmarket and offer a prize for the team that produces the best versions of the product. You let the crowd develop self-organised teams to do the work.

In many circumstances, you may find it easiest to design the product with macrotasking. With this strategy, you determine the way in which the product needs to be designed and divide the work into steps. You describe each step, place the description of each step on a crowdmarket, and select individual workers to compete those steps. (See Chapter 7 for more on macrotasking.)

Because you’re crowdsourcing, you can duplicate the work. You can hire two or three individuals to work on a single step, and you can then compare the results and choose the one that best meets your needs.

Testing, testing, testing

When you have a prototype product, you need to test it. If the product’s highly technical, you are likely to handle this step with macrotasking. You describe what needs to be done to test the product, post the description on a crowdmarket, and hire individuals to do the testing. Again, you can (and should) hire multiple people to do the tests and you then compare the results.

You can test some products, such as computer applications and programs, with companies that offer crowdsourcing test services. These firms have developed regimented ways of testing products and guide a crowd through the process. uTest (www.utest.com) and TopCoder (www.topcoder.com) are examples of firms that test software.

Giving the product to the world

Finally, you can move the product to market with the crowd. Crowdsourcing offers a variety of ways to do preliminary marketing:

![]() In a crowdcontest (see Chapter 5), you can reward people for distributing the product.

In a crowdcontest (see Chapter 5), you can reward people for distributing the product.

![]() In microtasking (see Chapter 8), you can pay the crowd to promote the product in one or two places.

In microtasking (see Chapter 8), you can pay the crowd to promote the product in one or two places.

![]() In crowdfunding (see Chapter 6), you can use the crowd to simultaneously sell an initial offering and raise funds for production.

In crowdfunding (see Chapter 6), you can use the crowd to simultaneously sell an initial offering and raise funds for production.

Considering an Example: Restructuring a Business with InnoCentive

To better understand how innovation crowdsourcing works, consider the problem of restructuring a small business.

Most of Riordan’s employees are young men who have limited prospects because they have only limited reading and writing skills. Riordan decides to determine whether his business can be restructured to help educate these young men. He’s aware of the perils of combining education and work, and has long been suspicious of companies that try to achieve social goals. He claims that such companies always fail at both efforts, are never very profitable and rarely do any good. Still, Riordan has reached a point in his life where he feels that he has to do something to improve the lot of his workers. He decides that a combination of new technology and a management system may help him accomplish his goals.

In planning his innovation, Riordan identifies a few basic goals. He needs to ensure that the new technology and system:

![]() Do not interfere with the operation of the warehouse – capacity and speed of operation are unchanged

Do not interfere with the operation of the warehouse – capacity and speed of operation are unchanged

![]() Teach mathematics and reading skills

Teach mathematics and reading skills

![]() Give the workers an incentive to engage with the lessons and learn

Give the workers an incentive to engage with the lessons and learn

In addition to these goals, Riordan has a few financial constraints. He has outside investors and a board that keeps him to a tight budget. He has $250,000 (roughly £160,000) to invest in this innovation, and after three years, he’ll need to see a regular 5 per cent return on that investment.

Before he goes any further, Riordan needs to determine whether this approach is feasible. A simple way to get feedback on the idea is to pose it as a challenge on an innovation website. Because the idea involves technology and social good, Riordan could try posting it on InnoCentive (www.innocentive.com), which offers a variety of crowdsourcing services.

Despite myths to the contrary, innovation doesn’t occur in a flash of inspiration. Ideas need to be refined before they can solve the problem at hand. So the first step in this process is to assess Riordan’s idea, to determine whether it has any merit at all or is merely the dream of an idealist who hopes that somehow capitalism may be able to accomplish a little more than merely providing a steady return on investments.

To assess the idea, Riordan utilises the InnoCentive Brainstorm Challenge. The Brainstorm Challenge is a simple product, common to many innovation sites, that enables him to post a question to the crowd and receive their proposals in return. To run one of these contests, he needs to describe his problem. In addition to the information given at the start of this section, he may need to describe the nature and size of his business, the size of his workforce, and the nature of the employees who work for him.

Before posting the challenge, Riordan also has to set a prize. The InnoCentive Brainstorm Challenges are small-prize contests, offering between $500 (£315) and $2,000 (£1,260). For a contest like this, in which he really wants an assessment of his idea, Riordan probably needs to offer something close to $2,000 (£1,260).

Riordan also needs to create a process to judge the contest. The contest runs for 30 days before the submissions are reviewed. For the simple InnoCentive contests, he needs to recruit a panel of judges. If he wants Innocentive to organise the panel, he needs to move up to the next category of crowdsourced innovation.

Riordan needs to keep the support of his board throughout the process, so he asks a couple of board members to serve as judges. Because the board members are likely to prefer ideas that are more focused on profit than on social good, he also recruits a local social worker and a couple of professors from the local college. He’s aware that he may have a panel that has too many different opinions to come to a consensus, but overall he thinks that the individuals make up a good panel and that if they can agree on any idea then Riordan should be able to make it work.

For the first weeks of the innovation contest, Riordan receives few viable ideas. Most ideas involve simply giving money to the workers rather than trying to educate them. Indeed, one of the judges complains that they should stop trying to change the company and merely give half the money to a local soup kitchen.

However, eventually a programmer suggests a new computer system to manage the warehouse that could also be used to train workers. The system he proposes uses computer simulation to find the best way of managing storage. The same program could be adapted to train workers how to manage a facility and combined with some distance-learning systems to improve the workers’ reading and mathematical skills. The crowd refines the idea, and suggests how Riordan could give workers time to train themselves and how he could use badges and other incentives to motivate the workers.

The cost of the new system is slightly more than Riordan wanted to pay, but the board members accept the idea because they had a hand in creating it. Riordan then begins the process of starting the new system.

People who help organisations innovate usually identify two kinds of processes to develop innovative ideas:

People who help organisations innovate usually identify two kinds of processes to develop innovative ideas: Finding better ways of storing energy

Finding better ways of storing energy In crowdsourcing for novelty, you seek something that may have no obvious value beyond its newness. Crowds can react in inconsistent ways to novel ideas. If the members of your crowd are talking among themselves, they can easily start following the opinions of a few vocal people who believe that one of the ideas is truly new. This is an example of the

In crowdsourcing for novelty, you seek something that may have no obvious value beyond its newness. Crowds can react in inconsistent ways to novel ideas. If the members of your crowd are talking among themselves, they can easily start following the opinions of a few vocal people who believe that one of the ideas is truly new. This is an example of the