CHAPTER 2

IT Governance and Management

This chapter discusses the following topics:

• IT governance structure

• Human resources management

• IT policies, standards, processes, and procedures

• Management practices

• IT resource investment, use, and allocation practices

• IT contracting and contract management strategies and practices

• Risk management practices

• Monitoring and assurance

• Business continuity planning

This chapter covers CISA Domain 2, “Governance and Management of IT.” The topics in this chapter represent 16 percent of the CISA examination.

IT governance should be the wellspring from which all other IT activities flow.

Properly implemented, governance is a process whereby senior management exerts strategic control over business functions through policies, objectives, delegation of authority, and monitoring. Governance is management’s control over all other IT processes to ensure that IT processes continue to effectively meet the organization’s business objectives.

Organizations usually establish governance through an IT steering committee that is responsible for setting long-term IT strategy, and by making changes to ensure that IT processes continue to support IT strategy and the organization’s needs. This is accomplished through the development and enforcement of IT policies, requirements, and standards.

IT governance typically focuses on several key processes, such as personnel management, sourcing, change management, financial management, quality management, security management, and performance optimization. Another key component is the establishment of an effective organization structure and clear statements of roles and responsibilities. An effective governance program will use a balanced scorecard or other means to monitor these and other key processes, and through a process of continuous improvement, IT processes will be changed to remain effective and to support ongoing business needs.

IT Governance Practices for Executives and Boards of Directors

Governance starts at the top.

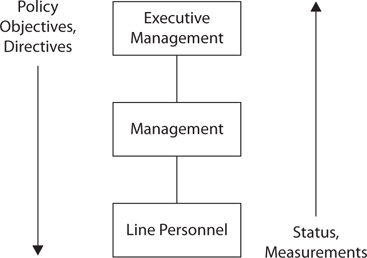

Whether the organization has a board of directors, council members, commissioners, or some other top-level governing body, governance begins with the establishment of top-level objectives and policies that are translated into more actions, policies, processes, procedures, and other activities downward through each level in the organization.

This section describes governance practices recommended for IT organizations, including a strategy-developing committee, measurement via the balanced scorecard, and security management.

IT Governance

The purpose of IT governance is to align the IT organization with the needs of the business. The term IT governance refers to a collection of top-down activities intended to control the IT organization from a strategic perspective to ensure that the IT organization supports the business. Some of the artifacts and activities that flow out of healthy IT governance include

• Policy At its minimum, IT policy should directly reflect the mission, objectives, and goals of the overall organization.

• Priorities The priorities in the IT organization should flow directly from the organization’s mission, objectives, and goals. Whatever is most important to the organization as a whole should be important to IT as well.

• Standards The technologies, protocols, and practices used by IT should be a reflection of the organization’s needs. On their own, standards help to drive a consistent approach to solving business challenges; the choice of standards should facilitate solutions that meet the organization’s needs in a cost-effective and secure manner.

• Vendor management The suppliers that IT selects should reflect IT priorities, standards, and practices.

• Program and project management IT programs and projects should be organized and performed in a consistent manner that reflects IT priorities and supports the business.

While IT governance contains the elements just described, strategic planning is also a key component of governance. Strategy is discussed in the next section.

IT Governance Frameworks

While every organization may have its unique missions, objectives, business models, tolerance for risk, and so on, organizations need not invent governance frameworks from scratch to manage their IT objectives. Several good frameworks can be adapted to meet organizations’ needs, including:

• COBIT This is an IT management framework developed by the IT Governance Institute and ISACA. COBIT’s five domains are Evaluate, Direct, and Monitor; Align, Plan, and Organize; Build, Acquire, and Implement; Deliver, Service, and Support; and Monitor, Evaluate, and Assess.

• ISO/IEC 27001 This is the well-known international standard for top-down information security management. In the context of IT security governance, what’s important here is the requirements in ISO/IEC 27001, not the controls that appear in its appendix.

• ITIL Formerly an acronym for IT Infrastructure Library, ITIL is a framework of processes for IT service delivery. ITIL was originally sponsored by the UK Office of Government Commerce in order to improve its IT management processes, and is now owned by AXELOS. The international standard, ISO/IEC 20000, is adapted from ITIL.

• ISO/IEC 38500 This is an international standard on corporate governance of information technology, suitable for small and large organizations in the public or private sector.

These and other frameworks are discussed in greater detail in Appendix B.

IT Strategy Committee

In organizations where IT provides significant value, the board of directors should have an IT strategy committee. This group will advise the board of directors on strategies to enable better IT support of the organization’s overall strategy and objectives.

The IT strategy committee can meet with the organization’s top IT executives to impart the board’s wishes directly to them. This works best as a two-way conversation, where IT executives can inform the strategy committee of their status on major initiatives, as well as on challenges and risks. This ongoing dialogue can take place as often as needed, usually once or twice per year.

Readers should note that this suggestion of the IT strategy committee communicating with IT management is not an attempt to circumvent communications through intermediate layers of management. Those individuals should be included in this conversation as well.

The Balanced Scorecard

The balanced scorecard (BSC) is a management tool that is used to measure the performance and effectiveness of an organization. The balanced scorecard is used to determine how well an organization can fulfill its mission and strategic objectives, and how well it is aligned with overall organizational objectives.

In the balanced scorecard, management defines key performance indicators in each of four perspectives:

• Financial Key financial items measured include the cost of strategic initiatives, support costs of key applications, and capital investment.

• Customer Key measurements include the satisfaction rate with various customer-facing aspects of the organization.

• Internal processes Measurements of key activities include the number of projects and the effectiveness of key internal workings of the organization.

• Innovation and learning Human-oriented measurements include turnover, illness, internal promotions, and training.

Each organization’s balanced scorecard will represent a unique set of measurements that reflects the organization’s type of business, business model, and style of management.

The balanced scorecard methodology of greatest interest to readers of this book is the standard IT balanced scorecard, discussed in the next section.

The Standard IT Balanced Scorecard

The balanced scorecard should be used to measure overall organizational effectiveness and progress. A similar scorecard, the standard IT balanced scorecard (IT-BSC), can be used to specifically measure IT organization performance and results.

Like the balanced scorecard, the standard IT balanced scorecard has four perspectives:

• Business contribution Key indicators here are the perception of IT department effectiveness and value as seen from other (non-IT) corporate executives.

• User Key measurements include end-user satisfaction rate with IT systems and the IT support organization. Satisfaction rates of external users should be included if the IT department builds or supports externally facing applications or systems.

• Operational excellence Key measurements include the number of support cases, amount of unscheduled downtime, and defects reported.

• Innovation This includes the rate at which the IT organization utilizes newer technologies to increase IT value and the amount of training made available to IT staff.

The IT balanced scorecard should flow directly out of the organization’s overall balanced scorecard. This will ensure that IT will align itself with corporate objectives. While the perspectives between the overall BSC and the IT-BSC vary, the approach for each is similar, and the results for the IT-BSC can “roll up” to the organization’s overall BSC.

Information Security Governance

Security governance is the collection of management activities that establishes key roles and responsibilities, identifies and treats risks to key assets, and measures key security processes. Depending upon the structure of the organization and its business purpose, information security governance may be included in IT governance, or security governance may stand on its own (but if so, it should still be linked to IT governance so that these two activities are kept in sync).

The main roles and responsibilities for security should be

• Board of directors The board is responsible for establishing the tone for risk appetite and risk management in the organization. To the extent that the board of directors establishes business and IT security, so, too, should the board consider risk and security in that strategy.

• Steering committee The security steering committee should establish the operational strategy for security and risk management in the organization. This includes setting strategic and tactical roles and responsibilities in more detail than was done by the board of directors. The security strategy should be in harmony with the strategy for IT and the business overall. The steering committee should also ratify security policy and other strategic policies and processes developed by the chief information security officer (CISO).

• Chief information security officer (CISO) The CISO should be responsible for developing security policy; conducting risk assessments; developing processes for vulnerability management, incident management, identity and access management, security awareness and training, and compliance management; and informing the steering committee and board of directors of incidents and new or changed risks. In some organizations, this is known as the chief information risk officer (CIRO).

• Chief information officer (CIO) The CIO is responsible for overall management of the IT organization, including IT strategy, development, operations, and service desk. In some organizations the CISO or other top-ranking security individual reports to the CIO, while in other organizations they are peers.

• Management Every manager in the organization should be at least partially responsible for the conduct of their employees. This approach helps to establish a chain of accountability from the top of the organization, all the way down to individual employees.

• All employees Every employee in the organization should be required to comply with the organization’s security policy, as well as with security requirements and processes. All senior and executive management should demonstrably comply with these policies as an example for others.

Security governance is not only for the identification and enforcement of applicable laws, regulations, and other legal requirements, but also for the fulfillment of goals and objectives, as well as management of policies and processes.

Security governance should also make it clear that compliance with policies is a condition of employment; employees who fail to comply with policy are subject to discipline or termination of employment.

Reasons for Security Governance

Organizations are dependent on their information systems. This has progressed to the point where organizations—including those whose products or services are not information-related—are completely dependent on the integrity and availability of their information systems to continue operations. Security governance, then, is needed to ensure that security-related incidents do not threaten critical systems and their support of the ongoing viability of the organization.

Security Governance Activities and Results

Within an effective security governance program, the organization’s management will see to it that information systems necessary to support business operations will be adequately protected. Some of the activities that will take place include

• Risk management Management will make sure that risk assessments will be performed to identify risks in information systems. Follow-up actions will be carried out that will reduce the risk of system failure and compromise.

• Process improvement Management will ensure that key changes will be made to business processes that will result in security improvements.

• Incident response Management will put incident response procedures into place that will help to avoid incidents, reduce the impact and probability of incidents, and improve response to incidents so that their impact on the organization is minimized.

• Improved compliance Management will be sure to identify all applicable laws, regulations, and standards and carry out activities to confirm that the organization is able to attain and maintain compliance.

• Business continuity and disaster recovery planning Management will define objectives and allocate resources for the development of business continuity and disaster recovery plans.

• Effectiveness measurement Management will establish processes to measure key security events such as incidents, policy changes and violations, audits, and training.

• Resource management The allocation of manpower, budget, and other resources to meet security objectives is monitored by management.

• Improved IT governance An effective security governance program will result in better strategic decisions in the IT organization that keep risks at an acceptably low level.

These and other governance activities are carried out through scripted interactions among key business and IT executives at regular intervals. Meetings will include a discussion of effectiveness measurements, recent incidents, recent audits, and risk assessments. Other discussions may include such things as changes to the business, recent business results, and any anticipated business events such as mergers or acquisitions.

Two key results of an effective security governance program are

• Increased trust Customers, suppliers, and partners trust the organization to a greater degree when they see that security is managed effectively.

• Improved reputation The business community, including customers, investors, and regulators, will hold the organization in higher regard.

IT Strategic Planning

In a methodical and organized way, a good strategic planning process answers the question of what to do, often in a way that takes longer to answer than it does to ask. While IT organizations require personnel who perform the day-to-day work of supporting systems and applications, some IT personnel need to spend at least part of their time developing plans for what the IT organization will be doing two, three, or more years in the future.

Strategic planning needs to be part of a formal, iterative planning process, not an ad hoc, chaotic activity. Specific roles and responsibilities for planning need to be established, and those individuals must carry out planning roles as they would any other responsibility. A part of the struggle with the process of planning stems from the fact that strategic planning is partly a creative endeavor that includes analysis of reliable information about future technologies and practices, as well as long-term strategic plans for the organization itself. In a nutshell, the key question is In five years, when the organization will be performing specific activities in a particular manner, how will IT systems support those activities?

But it’s more than just understanding how IT will support future business activities. Innovations in IT may help to shape what activities will take place, or at least how they will take place. On a more down-to-earth level, IT strategic planning is about the ability to provide the capability and capacity for IT services that will match the levels of and the types of business activities that the organization expects to achieve at certain points in the future. In other words, if organization strategic planning predicts specific transaction volumes (as well as new types of transactions) at specific points in the future, then the job of IT strategic planning will be to ensure that cost-effective IT systems of sufficient processing capacity will be up and running to support those features and workloads.

Discussion of new business activities, as well as the projected volume of current activities at certain times in the future, is most often discussed by a steering committee.

The IT Steering Committee

A steering committee is a body of senior managers or executives that meets from time to time to discuss high-level and long-term issues in the organization. An IT steering committee will typically discuss the future states of the organization and how the IT organization will meet the organization’s needs. A steering committee will typically consist of senior-level IT managers as well as key customers or constituents. This provider-customer dialogue will help to ensure that IT, as the organization’s technology service arm, will fully understand the future vision of the business (in business terms) and be able to support future business activities in terms of capacity, cost-effectiveness, and the ability to support new activities that do not yet exist.

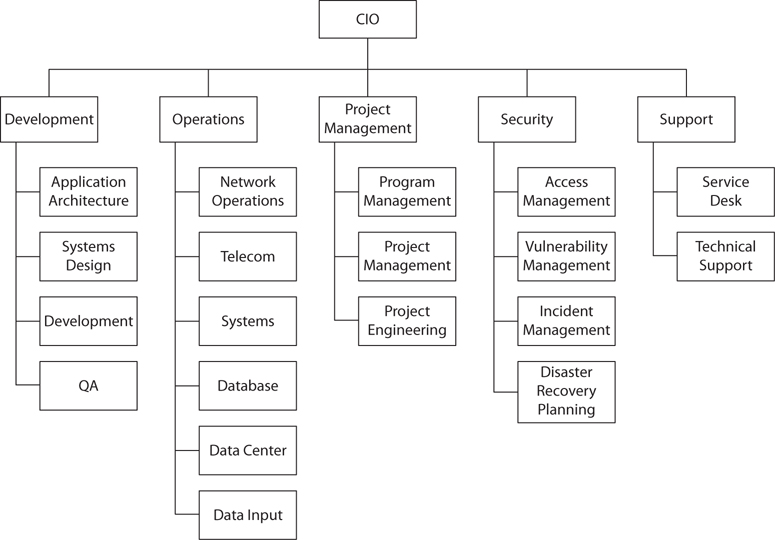

The role of the IT steering committee is depicted in Figure 2-1.

Figure 2-1 The IT steering committee synthesizes a future strategy using several inputs.

A steering committee’s mission, objectives, roles, and responsibilities should be formally defined in a written charter. Steering committee meetings should be documented and published.

The steering committee needs to meet regularly to consider strategic issues and make decisions that translate into actions, tasks, and projects in IT and elsewhere.

Not all organizations have an IT steering committee. The role is sometimes filled by key senior staff members, with or without an official charter. And in some organizations, the role is not filled at all, and as a result the IT organization is directionless.

Policies, Processes, Procedures, and Standards

Policies, processes, procedures, and standards define IT organizational behavior and uses of technology. They are part of the written record that defines how the IT organization performs the services that support the organization.

Policy documents should be developed and ratified by IT management. Policies state only what must be done (or not done) in an IT organization. They should not state how something must be done (or not done). That way, a policy document will be durable—meaning it may last many years with only minor edits from time to time.

IT policies typically cover many topics, including:

• Roles and responsibilities This will range from general to specific, usually by describing each major role and responsibility in the IT department and then specifying which position is responsible for it. IT policies will also make general statements about responsibilities that all IT employees will share.

• Development practices IT policy should define the processes used to develop and implement software for the organization. Typically, IT policy will require a formal development methodology that includes a number of specific ingredients, such as quality review and the inclusion of security requirements and testing.

• Operational practices IT policy defines the high-level processes that constitute IT’s operations. This will include service desk, backups, system monitoring, metrics, and other day-to-day IT activities.

• IT processes, documents, and records IT policy will define other important IT processes, including incident management, project management, vulnerability management, and support operations. IT policy should also define how and where documents such as procedures and records will be managed and stored.

IT policy, like any other organization policy, is generally focused on what should be done and on what parties are responsible for different activities. However, policy generally steers clear of describing how these activities should be performed. That, instead, is the role of procedures and standards, discussed later in this section.

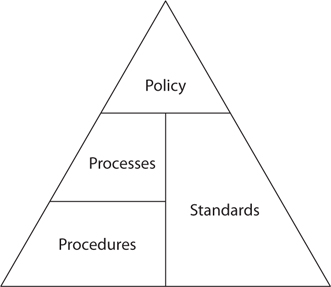

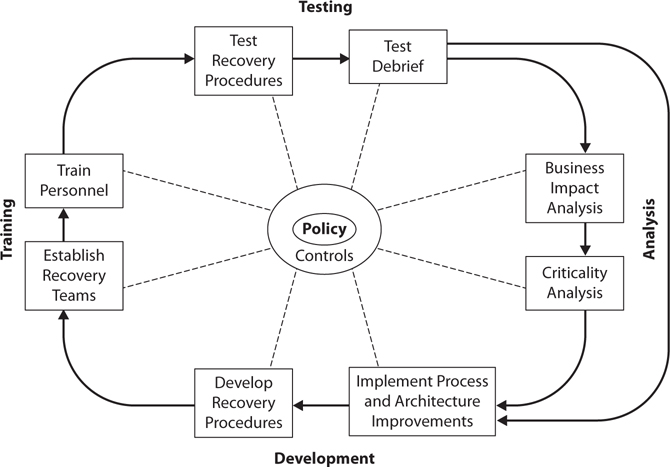

The relationship between policies, processes, procedures, and standards is shown in Figure 2-2.

Figure 2-2 Policies, processes, procedures, and standards

Information Security Policy

Security policy defines how an organization will protect its important assets. Like IT policy, information security policy defines several fundamental principles and activities:

• Roles and responsibilities Security policy should define specific roles and responsibilities, including the roles of specific positions in the organization as well as the responsibilities of all staff members.

• Risk management Security policy should define how the organization identifies and treats risks. An organization should perform periodic risk assessments and risk analysis, which will lead to decisions about risk treatment for specific risks that are identified.

• Security processes Security policy should define important security processes, such as vulnerability management and incident management, and incorporate security in other business processes, such as software development and acquisition, vendor selection and management, and employee screening and hiring.

• Acceptable use Security policy should define the types of activities that are acceptable and those that are not.

The best practice for information security policy is the definition of a top-down, management-driven information security program that performs periodic risk assessments to identify and focus on the most important risks in the organization. Roles and responsibilities define who is responsible for carrying out these activities. Executive management should have visibility and decision-making power, particularly in the areas of policy review and risk treatment.

It is generally accepted that security policy and security management should be separate from IT policy and IT management. This permits the security organization function to operate outside of IT, thereby permitting security to be objective and independent of IT. This puts security in a better position to be able to objectively assess IT systems and processes without fear of direct reprisal.

Privacy Policy

One of the most important policies an organization will develop that is related to information security is a privacy policy. A privacy policy describes how the organization will treat information that is considered private because it is related to a private citizen. A privacy policy defines two broad activities in this regard:

• Protecting private information An organization that is required to collect, store, or transmit private information is duty-bound to protect this information so that it is not disclosed to unauthorized parties. This part of a privacy policy will describe what information is obtained and how it is protected.

• Handling private information Aside from the actual protection of private information, some organizations may, in the course of their business activities, transmit some or all of this information to other parts of the organization or to other organizations. A privacy policy is typically forthright about this internal handling and the transmittals to other parties. Further, a privacy policy describes how the information is used by the organization and by other organizations to which it is transmitted. The privacy policy typically describes how a private citizen may confirm whether his or her private information is stored by the organization, whether it is accurate, and how the citizen can arrange for its removal if he or she wishes.

Data Classification Policy

A data classification policy defines degrees of sensitivity for various types of information used in the organization. A typical data classification policy will define two or more (but rarely more than five) data classification levels. For example:

• Top Secret

• Secret

• Sensitive

• Public

Along with defining levels of classification, a data classification policy will define policies and procedures for handling of information in various settings at these levels. For instance, a data classification policy will state the conditions at each level in which sensitive information may be e-mailed, faxed, stored, transmitted, or shipped. Note that some methods for handling may be forbidden—such as e-mailing a top-secret document.

System Classification Policy

A data classification policy may specify levels of security for systems storing classified information. A system classification policy will establish levels of system security that correspond to levels of data classification. Such a policy will help the organization to be more deliberate in its system hardening standards so that the most sensitive information will be stored only on systems with the highest levels of hardening (often, those higher levels of hardening are more costly and time consuming to manage; otherwise, an organization might just make all of its systems as secure).

Site Classification Policy

A site classification policy defines levels of security for an organization’s work sites. This policy sets levels of physical security that corresponds to one or more factors:

• Criticality of staff that works at the site

• Criticality or value of business processes performed at the site

• Value of assets located at the site

• Sensitivity or value of data stored or processed at the site

• Siting risks associated with a site (human-made or natural hazards)

Based on the classification of a site, an organization may have additional security controls, such as video surveillance, guards, fences, visitor controls, and so on. Just as it does not make sense to protect all data at a single level, it also is sensible to have the right level of physical security at each site according to the information, equipment, or activity that takes place there.

Access Control Policy

An access control policy defines the need for specific processes and procedures related to the granting, review, and revocation of access to systems and work areas. This policy will state which roles are permitted to manage access controls, what levels of approval are required for access requests, how often access reviews will take place, and what access control records will be kept.

Often, there will be linkage between a data classification policy and an access control policy, since access controls protecting the most sensitive information may be stricter than access controls protecting less sensitive information.

Mobile Device Policy

A mobile device policy defines the use of mobile devices and personally owned devices in the context of business operations and access to business information and information systems. This policy will state the types of devices that may be permitted, the rules and conditions of their use, and responsibilities of device owners and users.

Social Media Policy

A social media policy defines employees’ use of social media. Generally, this encompasses online behavior and employees’ online representations of their personal and professional conduct. Components in a social media policy may include

• Personal social media Policy may limit the posting of content that could put the employee or the organization in a bad light.

• Professional social media Policy may address or restrict how employees describe their positions and activities in the workplace.

• Disclosure of company information Policy may restrict the types of information that employees are permitted to disclose to the public.

While organizations generally don’t try to restrict employees’ use of social media, organizations use social media policy to reaffirm their ownership of official information about the organization.

Other Policies

Organizations may have additional technology-related policies, including:

• Equipment control and use Policy may address the appropriate use of IT and other equipment, and perhaps includes cases where equipment is assigned to employee use in the field.

• Data destruction Policy defines acceptable and required methods for the disposal of information when no longer needed.

• Moonlighting Policy addresses matters regarding outside employment, such as employees who have a second job or perform volunteer work.

Processes and Procedures

Process and procedure documents, sometimes called SOPs (standard operating procedures), describe in step-by-step detail how IT processes and tasks are performed. Formal procedure documents ensure that tasks are performed consistently and correctly, even when performed by different IT staff members.

In addition to the actual steps in support of a process or task, a procedure document needs to contain several pieces of metadata:

• Document (or process) ownership The document should contain the name of the person or department responsible for its review, revision, and publication.

• Document revision information The procedure document should contain the name of the person who wrote the document and the person who made the most recent changes to the document. The document should also include the name or location where the official copy of the document may be found.

• Review and approval The document should include the name of the manager who last reviewed the procedure document, as well as the name of the manager (or higher) who approved the document.

• Dependencies The document should specify which other procedures are related to this procedure. This includes those procedures that are dependent upon this procedure, and the procedures that this one depends on. For example, a document that describes the database backup process will depend on database management and maintenance documents; documents on media handling will depend on this document.

IT process and procedure documents are not meant to be a replacement for vendor task documentation. For instance, an IT department does not necessarily need to create a document that describes the steps for operating a data storage device when the device vendor’s instructions are available and sufficient. Also, IT procedure documents need not be remedial and include every specific keystroke and mouse click: they can usually assume that the reader has experience in the subject area and only needs to know how things are done in this organization. For example, a procedure document that includes a step that involves the modification of a configuration file does not need to include instructions on how to operate a text editor.

Standards

IT standards are official, management-approved statements that define the technologies, protocols, suppliers, and methods that are used by an IT organization. Standards help to drive consistency into the IT organization, which will make the organization more cost-efficient and cost-effective.

An IT organization will have different types of standards, including:

• Technology standards These standards specify what software and hardware technologies or products are used by the IT organization. Examples include operating system, database management system, application server, storage systems, backup media, and so on.

• Protocol standards These standards specify the protocols that are used by the organization. For instance, an IT organization may opt to use Transmission Control Protocol/Information Protocol (TCP/IP) v6 for its internal networks, Cisco gateway routing protocols (GRP), Transport Layer Security (TLS) for secure transmission of data, Secure Shell (SSH) for device management, and so forth.

• Supplier standards This defines which suppliers and vendors are used for various types of supplies and services. Using established suppliers can help the IT organization through specially negotiated discounts and other arrangements.

• Methodology standards This refers to practices used in various processes, including software development, system administration, network engineering, and end-user support.

• Configuration standards This refers to specific detailed configurations that are to be applied to servers, database management systems, end-user workstations, network devices, and so on. This enables users, developers, and technical administrative personnel to be more comfortable with IT systems because the systems will be consistent with each other. This helps to reduce unscheduled downtime and to improve quality.

• Architecture standards This refers to technology architecture at the database, system, or network level. An organization may develop reference architectures for use in various standard settings. For instance, a large retail organization may develop specific network diagrams to be used in every retail location, down to the colors of wires to use and how equipment is situated on racks or shelves.

Applicable Laws, Regulations, and Standards

Organizations need to identify all of the laws, regulations, and standards that are applicable to their operations. As information technology has become more critical for organizations in many industry sectors, many nations and local governments have enacted new laws and regulations concerning the processing and protection of information.

The board of directors, strategy committee, or chief legal counsel should appoint an executive to be responsible for identifying all potentially applicable laws and regulations, who should then consult with inside or outside legal counsel to determine their scope and applicability.

Once applicable laws and regulations have been identified, the organization then needs to determine how they affect

• Enterprise architecture Laws and regulations may require that organizations put specific IT components or configurations into place that affect the organization’s enterprise architecture.

• Controls Laws and regulations may require that additional controls be enacted or existing controls changed.

• Processes Laws and regulations may require that the organization perform certain tasks that may affect processes.

• Personnel Laws and regulations may require that certain personnel possess specific qualifications, certifications, or licenses.

Many factors will determine whether specific laws are applicable to an organization, including:

• Type of data that is stored, processed, or transmitted by the organization’s systems

• Industry sector

• Location of stored, processed, or transmitted data

• Location of the owner(s) of stored, processed, or transmitted data

Organizations may also be required to comply with specific standards. For example, organizations that process, store, or transmit credit card numbers may be required to comply with the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS), even though there may be no laws requiring organizations to do so.

Risk Management

Organizations need to understand the internal activities, practices, and systems, as well as external threats, that are introducing risk into their operations. The span of activities that seek, identify, and manage these risks is known as risk management. Like many other processes, risk management is a life cycle activity that has no beginning and no end. It’s a continuous and phased set of activities that includes the examination of processes, records, systems, and external phenomena in order to identify risks. This is continued by an analysis that examines a range of solutions for reducing or eliminating risks, followed by formal decision-making that brings about a resolution to risks.

Risk management needs to support overall business objectives. This support will include the adoption of a risk appetite that reflects the organization’s overall approach to risk. For instance, if the organization is a conservative financial institution, then that organization’s risk management program will probably adopt a position of being risk averse. Similarly, a high-tech startup organization that, by its very nature, is comfortable with overall business risk will probably be less averse to risks identified in its risk management program.

Regardless of its overall risk appetite, when an organization identifies risks, the organization can take one of four possible actions:

• Accept The organization accepts the risk as-is.

• Mitigate (or Reduce) The organization takes action to reduce the level of risk.

• Transfer (or Share) The organization shares the risk with another entity, usually an insurance company.

• Avoid The organization discontinues the activity associated with the risk.

These alternatives are known as risk treatments. Often, a particular risk will be treated with a blended solution that consists of two or more of the actions just listed.

This section dives into the details of risk management, risk analysis, and risk treatment.

The Risk Management Program

An organization that operates a risk management program should establish principles that will enable the program to succeed. These may include

• Objectives The risk management program must have a specific purpose; otherwise, it will be difficult to determine whether the program is successful. Example objectives include reducing the number of industrial accidents, reducing the cost of insurance premiums, or reducing the number of stolen assets. If objectives are measurable and specific, then the individuals who are responsible for the risk management program can focus on its objectives in order to achieve the best possible outcome.

• Scope Management must determine the scope of the risk management program. This is a fairly delicate undertaking because of the many interdependencies found in IT systems and business processes. However, in an organization with several distinct operations or business units (BUs), a risk management program could be isolated to one or more operational arms or BUs. In such a case, where there are dependencies on other services in the organization, those dependencies can be treated like an external service provider (or customer).

• Authority The risk management program is being started at the request of one or more executives in the organization. It is important to know who these individuals are and their level of commitment to the program.

• Roles and responsibilities This defines specific job titles, together with their respective roles and responsibilities in the risk management program. In a risk management program with several individuals, it should be clear which individuals or job titles are responsible for which activities in the program.

• Resources The risk management program, like other activities in the business, requires resources to operate. This will include a budget for salaries as well as for workstations, software licenses, and possibly travel.

• Policies, processes, procedures, and records The various risk management activities, such as asset identification, risk analysis, and risk treatment, along with some general activities like recordkeeping, should be written down.

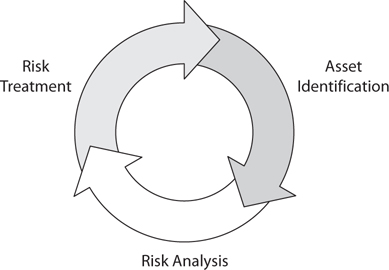

The risk management life cycle is depicted in Figure 2-3.

Figure 2-3 The risk management life cycle

The Risk Management Process

Risk management is a life cycle set of activities used to identify, analyze, and treat risks. These activities are methodical and, as mentioned in the previous section, should be documented so that they will be performed consistently and in support of the program’s charter and objectives.

The risk management process is a part of a larger risk framework, such as ISACA’s Risk IT Framework, whose components are

• Risk Governance This includes integration with the organization’s enterprise risk management (ERM), the establishment and maintenance of a common risk view, and the ensurance that business decisions include the consideration of risk.

• Risk Evaluation This includes asset identification, risk analysis, and the maintenance of a risk profile.

• Risk Response This includes the management and articulation of risks, and response to events.

CISA candidates are not required to memorize the Risk IT Framework, but familiarity with its principles are important.

Asset Identification

The risk management program’s main objective (whether formally stated or not) is the protection of the organization’s assets. These assets may be tangible or intangible, physical, logical, or virtual. Some examples of assets include

• Buildings and property These assets include structures and other improvements.

• Equipment This can include machinery, vehicles, and office equipment such as copiers and fax machines.

• IT equipment This includes computers, printers, scanners, tape libraries (the devices that create backup tapes, not the tapes themselves), storage systems, network devices, and phone systems.

• Supplies and materials These can include office supplies as well as materials that are used in manufacturing.

• Records These include business records, such as contracts, video surveillance tapes, visitor logs, and far more.

• Information This includes data in software applications, documents, e-mail messages, and files of every kind on workstations and servers.

• Intellectual property This includes an organization’s designs, architectures, software source code, processes, and procedures.

• Personnel In a real sense, an organization’s personnel are the organization. Without its staff, the organization cannot perform or sustain its processes.

• Reputation One of the intangible characteristics of an organization, reputation is the individual and collective opinion about an organization in the eyes of its customers, competitors, shareholders, and the community.

• Brand equity Similar to reputation, this is the perceived or actual market value of an individual brand of product or service that is produced by the organization.

Grouping Assets For risk management purposes, an electronic inventory of assets will be useful in the risk management life cycle. It is not always necessary to list each individual asset: often, it is acceptable to instead list classes or groups of assets as a single asset entity for risk management purposes. For instance, a single entry for laptop computers may be preferred over listing every laptop computer; this is because the risks for all laptop computers are roughly the same (ignoring behavior differences among individual employees or employees in specific departments). This eliminates the need to list them individually.

Similarly, groups of IT servers, network devices, and other equipment can be named instead of all of the individual servers and devices, again because the risks for each of them will usually be similar. However, one reason to create multiple entries for servers might be their physical location or their purpose: servers in one location may have different risks than servers in another location, and servers containing high-value information will have different risks than servers that do not contain high-value information.

Sources of Asset Data An organization that is undergoing its initial risk-management cycle may need to build its asset database from scratch. Management will need to determine where this initial asset data will come from. Some choices include

• Financial system asset inventory An organization that keeps all of its assets on the books will have a wealth of asset inventory information. However, it may not be entirely useful: asset lists often do not include the location or purpose of the asset and whether it is still in use. Correlating a financial asset inventory to assets in actual use may consume more effort than the other methods for creating the initial asset. However, for organizations that have a relatively small number of highly valued assets (for instance, a rock crusher in a gold mine or a mainframe computer), knowing the precise financial value of an asset is highly useful because the actual depreciated value of the asset is used in the risk analysis phase of risk management. Knowing the depreciated value of other assets is also useful, as this will figure into the risk treatment choices that will be identified later on.

• Interviews Discussions with key personnel for purposes of identifying assets are usually the best approach. However, to be effective, several people usually need to be interviewed to be sure to include all relevant assets.

• IT systems portfolio A well-managed IT organization will have formal documents and records for its major applications. While this information may not encompass every single IT asset in the organization, it can provide information on the assets supporting individual applications or geographic locations.

• Online data An organization with a large number of IT assets (systems, network devices, and so on) can sometimes utilize the capability of local online data to identify those assets. For instance, a systems or network management system often includes a list of managed assets, which can be a good starting point when creating the initial asset list.

• Asset management system Larger organizations may find it more cost effective to use an asset management application dedicated to this purpose, rather than rely on lists of assets from other sources.

Collecting and Organizing Asset Data It is rarely possible to take (or create) a list of assets from a single source. Rather, more than one source of information is often needed to be sure that the risk management program has identified at least the important, in-scope assets that it needs to worry about.

It is usually useful to organize or classify assets. This will help to get the assets under study into smaller chunks that can be analyzed more effectively. There is no single way to organize assets, but a few ideas include

• Geography A widely dispersed organization may want to classify its assets according to their location. This will aid risk managers during the risk analysis phase, since many risks are geographic-centric, particularly natural hazards. Mitigation of risks is often geography based: for instance, it’s easier to make sense of building a fence around one data center than putting up fences around buildings in every location.

• Business process Because some organizations rank the criticality of their individual business processes, it can be useful to group assets according to the business processes that they support. This helps the risk analysis and risk treatment phases, because assets supporting individual processes can be associated with business criticality and treated appropriately.

• Organizational unit In larger organizations, it may be easier to classify assets according to the organizational unit they support.

• Sensitivity Usually ascribed to information, sensitivity relates to the nature and content of that information. Sensitivity usually applies in two ways: to an individual, where the information is considered personal or private, and to an organization, where the information may be considered a trade secret. Sometimes sensitivity is somewhat subjective and arbitrary, but often it is defined in laws and regulations.

• Regulation For organizations that are required to follow government or private regulation regarding the processing and protection of information, it will be useful to include data points that indicate whether specific assets are considered in scope for specific regulations. This is important because some regulations specify how assets should be protected, so it’s useful to be aware of this during risk analysis and risk treatment.

There is no need to choose which of these three methods will be used to classify assets. Instead, an IT analyst should collect several points of metadata about each asset (including location, process supported, and organizational unit supported). This will enable the risk manager to sort and filter the list of assets in various ways to better understand which assets are in a given location or which ones support a particular process or part of the business.

Risk Analysis

Risk analysis is the activity in a risk management program where individual risks are identified. A risk consists of the intersection of threats, vulnerabilities, probabilities, and impact. In its simplest terms, risk is described in the following formula:

Risk = Probability × Impact

This equation implies that risk is always used in quantitative terms, but risk is equally used in qualitative risk analysis.

Other definitions of risk include

• The combination of the probability of an event and its consequence (source: ISACA Cybersecurity Fundamentals Glossary)

• The probable frequency and probable magnitude of future loss (source: “An Introduction to Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR),” Risk Management Insight, LLC)

• The potential that a given threat will exploit vulnerabilities of an asset or group of assets and thereby cause harm to the organization (source: ISO/IEC 27005)

These definitions convey essentially the same message: the amount of risk is directly proportional to the probability of occurrence and the impact that a risk would have if realized.

A risk analysis consists of identifying threats and their impact of realization against each asset. This usually also includes a vulnerability analysis, where assets are studied to determine whether they are vulnerable to identified threats. The sheer number of assets may make this task appear daunting; however, threat and vulnerability analyses can usually be performed against groups of assets. For instance, when identifying natural and human-made threats against assets, it often makes sense to perform a single threat analysis against all of the assets that reside in a given location. After all, the odds of a volcanic eruption are the same for any of the servers in the room—the threat need not be called out separately for each asset.

Threat Analysis The usual first step in a risk analysis is to identify threats against an asset or group of assets. A threat is an event that, if realized, would bring harm to an asset and, hence, to the organization. A typical approach is to list all of the threats that have some realistic opportunity of occurrence; those threats that are highly unlikely to occur can be left out. For instance, the listing of meteorites, tsunamis in landlocked regions, and wars in typically peaceful regions will just add clutter to a risk analysis.

A more reasonable approach in a threat analysis is to identify all of the threats that a reasonable person would believe could occur, even if the probability is low. For example, include flooding when a facility is located near a river, hurricanes for an organization located along the southern or eastern coast (and inland for some distance) of the United States, or a terrorist attack in practically every major city in the world. All of these would be considered reasonable in a threat analysis.

It is important to include the entire range of both natural and human-made threats. The full list could approach or even exceed 100 separate threats. The categories of possible threats include

• Severe storms This may include tornadoes, hurricanes, windstorms, ice storms, and blizzards.

• Earth movement This includes earthquakes, landslides, avalanches, volcanoes, and tsunamis.

• Flooding This can include both natural and human-made situations.

• Disease This includes sickness outbreaks and pandemics, as well as quarantines that result.

• Fire This includes forest fires, range fires, and structure fires, all of which may be natural or human-caused.

• Labor This includes work stoppages, sick-outs, protests, and strikes.

• Violence This includes riots, looting, terrorism, and war.

• Malware This includes all kinds of viruses, worms, Trojan horses, root kits, and associated malicious software.

• Hacking attack This includes automated attacks (think of an Internet worm that is on the loose) as well as targeted attacks by employees, former employees, or criminals.

• Hardware failures This includes any kind of failure of IT equipment or related environmental equipment failures, such as heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC).

• Software failures This can include any software problem that precipitates a disaster. Examples are the software bug that caused a significant power blackout in the U.S. Northeast in 2003 and the Nest home thermostat bug in 2016.

• Utilities This includes electric power failures, water supply failures, and natural gas outages, as well as communications outages.

• Transportation This may include airplane crashes, railroad derailments, ship collisions, and highway accidents.

• Hazardous materials This includes chemical spills. The primary threat here is direct damage by hazardous substances, casualties, and forced evacuations.

• Criminal This includes extortion, embezzlement, theft, vandalism, sabotage, and hacker intrusion. Note that company insiders can play a role in these activities.

• Errors This includes mistakes made by personnel that result in disaster situations.

Alongside each threat that is identified, the risk analyst assigns a probability or frequency of occurrence. This may be a numeric value, expressed as a probability of one occurrence within a calendar year. For example, if the risk of a flood is 1 in 100, it would be expressed as 0.01, or 1 percent. Probability can also be expressed as a ranking; for example, Low, Medium, and High; or on a numeric probability scale from 1 to 5 (where 5 can be either highest or lowest probability).

An approach for completing a threat analysis is to

• Perform a geographic threat analysis for each location This will provide an analysis on the probability of each type of threat against all assets in each location.

• Perform a logical threat analysis for each type of asset This provides information on all of the logical (that is, not physical) threats that can occur to each asset type. For example, the risk of malware on all assets of one type is probably the same, regardless of their location.

• Perform a threat analysis for each highly valued asset This will help to identify any unique threats that may have appeared in the geographic or logical threat analysis, but with different probabilities of occurrence.

Threat Forecasting Data Is Sparse

One of the biggest problems with information security–related risk management is the lack of reliable data on the probability of many types of threats. While the probability of some natural threats can sometimes be obtained from local disaster response agencies, the probabilities of most other threats are difficult to accurately predict.

The difficulty in predicting security events sits in stark contrast to volumes of available data related to automobile and airplane accidents, as well as human life expectancy. In these cases, insurance companies have been accumulating statistics on these events for decades, and the variables (for instance, tobacco and alcohol use) are well known. On the topic of cyber-related risk, there is a general lack of reliable data, and the factors that influence risk are not well known from a statistical perspective. It is for this reason that risk analysis still relies on educated guesses for the probabilities of most events. But given the recent surge in popularity for cyber insurance, the availability and quality of cyber-attack risk factors may soon be determined.

Vulnerability Identification A vulnerability is a weakness or absence of a protective control that makes the probability of one or more threats more likely. A vulnerability analysis is an examination of an asset in order to discover weaknesses that could lead to a higher-than-normal rate of occurrence or potency of a threat.

Examples of vulnerabilities include

• Missing or inoperative antivirus software

• Outdated and unsupported software in use

• Missing security patches

• Weak password settings

• Missing or incomplete audit logs

• Inadequate monitoring of event logs

• Weak or defective application session management

• Building entrances that permit tailgating

In a vulnerability analysis, the risk manager needs to examine the asset itself as well as all of the protective measures that are—or should be—in place to protect the asset from relevant threats.

Vulnerabilities can be ranked by severity. Vulnerabilities are indicators that show the effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) of protective measures. For example, an antivirus program on a server that updates its virus signatures once per week might be ranked as a medium vulnerability, whereas the complete absence (or malfunction) of an antivirus program on the same server might be ranked as a high vulnerability. Severity is an indication of the likelihood that a given threat might be realized. This is different from impact, which is discussed later in this section.

Probability Analysis For any given threat and asset, the probability that the threat will actually be realized needs to be estimated. This is often easier said than done, as there is a lack of reliable data on security incidents. A risk manager still will need to perform some research and develop a best guess based on available data.

Impact Analysis A threat, when actually realized, will have some effect on the organization. Impact analysis is the study of estimating the impact of specific threats on specific assets.

In impact analysis, it is necessary to understand the relationship between an asset and the business processes and activities that the asset supports. The purpose of impact analysis is to identify the impact on business operations or business processes. This is because risk management is not an abstract identification of abstract risks, but instead a search for risks that have real impact on business operations.

In an impact analysis, the impact can be expressed as a rating such as H-M-L (High-Medium-Low) or as a numeric scale, and it can also be expressed in financial terms. But what is also vitally important in an impact analysis is the inclusion of a statement of impact for each threat. Example statements of impact include “inability to process customer support calls” and “inability for customers to view payment history.” Statements such as “inability to authenticate users” may be technically accurate, but they do not identify the business impact.

Qualitative Risk Analysis A qualitative risk analysis is an in-depth examination of in-scope assets with a detailed study of threats (and their probability of occurrence), vulnerabilities (and their severity), and statements of impact. The threats, vulnerabilities, and impact are all expressed in qualitative terms such as High-Medium-Low or in quasi-numeric terms such as a 1–5 numeric scale.

The purpose of qualitative risk analysis is to identify the most critical risks in the organization based on these rankings.

Qualitative risk analysis does not get to the issue of “how much does a given threat cost my business if it is realized?”—nor does it mean to. The value in a qualitative risk analysis is the ability to quickly identify the most critical risks without the additional burden of identifying precise financial impacts.

The individual(s) performing risk analysis may wish to include threat-vulnerability pairing as well as asset-threat pairing. These are techniques that may help a risk analyst better understand the probability or impact of specific threats.

Quantitative Risk Analysis Quantitative risk analysis is a risk analysis approach that uses numeric methods to measure risk. The advantage of quantitative risk analysis is the statements of risk in terms that can be easily compared with the known value of their respective assets. In other words, risks are expressed in the same units of measure as most organizations’ primary unit of measure: financial.

Despite this, quantitative risk analysis must still be regarded as an effort to develop estimates, not exact figures. Partly this is because risk analysis is a measure of events that may occur, not a measure of events that do occur.

Standard quantitative risk analysis involves the development of several figures:

• Asset value (AV) This is the value of the asset, which is usually (but not necessarily) the asset’s replacement value.

• Exposure factor (EF) This is the financial loss that results from the realization of a threat, expressed as a percentage of the asset’s total value. Most threats do not completely eliminate the asset’s value; instead, they reduce its value. For example, if a construction company’s $120,000 earth mover is destroyed in a fire, the equipment will still have salvage value, even if that is only 10 percent of the asset’s value. In this case the EF would be 90 percent. Note that different threats will have different impacts on EF because the realization of different threats will cause varying amounts of damage to assets.

• Single loss expectancy (SLE) This value represents the financial loss when a threat is realized one time. SLE is defined as AV × EF. Note that different threats have a varied impact on EF, so those threats will also have the same multiplicative effect on SLE.

• Annualized rate of occurrence (ARO) This is an estimate of the number of times that a threat will occur per year. If the probability of the threat is 1 in 50, then ARO is expressed as 0.02. However, if the threat is estimated to occur four times per year, then ARO is 4.0. Like EF and SLE, ARO will vary by threat.

• Annualized loss expectancy (ALE) This is the expected annualized loss of asset value due to threat realization. ALE is defined as SLE × ARO.

ALE is based upon the verifiable values AV, EF, and SLE, but because ARO is only an estimate, ALE is only as good as ARO. Depending upon the value of the asset, the risk manager may need to take extra care to develop the best possible estimate for ARO, based upon whatever data is available. Sources for estimates include

• History of event losses in the organization

• History of similar losses in other organizations

• History of dissimilar losses

• Best estimates based on available data

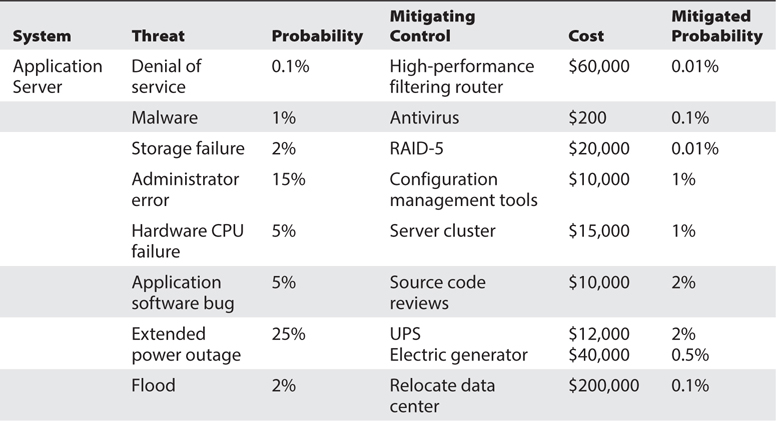

Developing Mitigation Strategies An important part of risk analysis is the investigation of potential solutions for reducing or eliminating risk. This involves understanding specific threats and their impact (EF) and likelihood of occurrence (ARO). Once a given asset and threat combination has been baselined (that is, the existing asset, threats, and controls have been analyzed to understand the threats as they exist right now), the risk analyst can then apply various hypothetical means for reducing risk, documenting each one in terms of its impact on EF and ARO.

For example, suppose a risk analysis identifies the threat of attack on a public web server. Specific EF and ARO figures have been identified for a range of individual threats. Now the risk analyst applies a range of fixes (on paper), such as an application firewall, an intrusion prevention system, and a patch management tool. Each solution will have a specific and unique impact on EF and ARO (these are all estimates, of course, just like the estimates of EF and ARO on the initial conditions); some will have better EF and ARO figures than others. Each solution should also be rated in terms of cost (financial or H-M-L) and effort to implement (financial or H-M-L).

While security analysts may have the responsibility for documenting vulnerabilities, threats, and risks, it is senior management’s responsibility (through the security steering committee) to formally approve the treatment of risk. Risk treatment is discussed later in this chapter.

Risk Analysis and Disaster Recovery Planning Disaster recovery planning (DRP) and business continuity planning (BCP) utilize risk analysis to identify risks that are related to application resilience and the impact of disasters. The risk analysis performed for DRP and BCP is the same risk analysis that is discussed in this chapter—the methods and approach are the same, although the overall objectives are somewhat different.

Business continuity planning is discussed in depth later in this chapter. Disaster recovery planning is discussed in detail in Chapter 5.

High-Impact Events The risk manager is likely to identify one or more high-impact events during the risk analysis. These events, which may be significant enough to threaten the very viability of the organization, require risk treatment that warrants executive management visibility and belongs in the categories of business continuity planning and disaster recovery planning. These topics are discussed in detail later in this chapter.

Risk Treatment

When risks to assets have been identified through qualitative or quantitative risk analysis, the next step in risk management is to decide what to do about the identified risks. In the risk analysis, one or more potential solutions may have been examined, along with their cost to implement and their impact on risk. In risk treatment, a decision about whether to proceed with any of the proposed solutions (or others) is needed.

Risk treatment pits available resources against the need to reduce risk. In an enterprise environment, not all risks can be mitigated or eliminated because there are not enough resources to treat them all. Instead, a strategy for choosing the best combination of solutions that will reduce risk by the greatest possible margin is needed. For this reason, risk treatment is often more effective when all the risks and solutions are considered together, instead of each one separately. Then they can be compared and prioritized.

When risk treatment is performed at the enterprise level, risk analysts and technology architects can devise ways to bring about the greatest possible reduction in risk. This can be achieved through the implementation of solutions that will reduce many risks for many assets at once. For example, a firewall can reduce risks from many threats on many assets; this will be more effective than individual solutions for each asset.

So far I have been talking about risk mitigation as if it were the only option available when handling risk. Rather, you have four primary ways to treat risk: mitigation, transfer, avoidance, and acceptance. And there is always some leftover risk, called residual risk. These four approaches are discussed here.

Risk Mitigation

Risk mitigation, or risk reduction, involves the implementation of some solution that will reduce an identified risk. For instance, the risk of advanced malware being introduced onto a server can be mitigated with advanced malware prevention software or a network-based intrusion prevention system. Either of these solutions would constitute mitigation of this risk on a given asset.

An organization usually makes a decision to implement some form of risk mitigation only after performing some cost analysis to determine whether the reduction of risk is worth the expenditure of risk mitigation.

Risk Transfer

Risk transfer, or sharing, means that some or all of the risk is being transferred to some external entity, such as an insurance company or business partner. When an organization purchases an insurance policy to protect an asset against damage or loss, the insurance company is assuming part of the risk in exchange for payment of insurance premiums.

The details of a cyber-insurance policy need to be carefully examined to be sure that any specific risk is transferrable to the policy. Cyber-insurance policies typically have exclusions that limit or deny payment of benefits in certain situations.

Risk Avoidance

In risk avoidance, the organization abandons the activity altogether, effectively taking the asset out of service so that the threat is no longer present. In another scenario, they may decide that the risk of pursuing a given business activity is too great, so they may decide to avoid that particular activity.

Risk Acceptance

Risk acceptance occurs when management is willing to accept an identified risk as-is, with no effort taken to reduce it. Risk acceptance also takes place (sometimes implicitly) for residual risk, after other forms of risk treatment have been applied.

Residual Risk

Residual risk is the risk that is left over from the original risk after some of the risk has been removed through mitigation or transfer. For instance, if a particular threat had a probability of 10 percent before risk treatment and 1 percent after risk treatment, the residual risk is that 1 percent left over. This is best illustrated by the following formula:

Original Risk – Mitigated Risk – Transferred Risk = Residual Risk

It is unusual for risk treatment to eliminate risk altogether; rather, various controls are implemented that remove some of the risk. Often, management implicitly accepts the leftover risk; however, it’s a good idea to make that acceptance of residual risk more formal by documenting the acceptance in a risk management log or a decision log.

Compliance Risk: The Risk Management Trump Card

Organizations that perform risk management are generally aware of the laws, regulations, and standards they are required to follow. For instance, U.S.-based banks, brokerages, and insurance companies are required to comply with the Gramm Leach Bliley Act (GLBA), and organizations that store, process, or transmit credit card numbers are required to comply with PCI-DSS (Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard).

GLBA, PCI-DSS, and other regulations often state in specific terms what controls are required in an organization’s IT systems. This brings to light the matter of compliance risk. Sometimes, the risk associated with a specific control (or lack of a control) may be rated as a low risk, either because the probability of a risk event is low or because the impact of the event is low. However, if a given law, regulation, or standard requires that the control be enacted anyway, then the organization must consider the compliance risk. The risk of noncompliance may result in fines or other sanctions against the organization, which may (or may not) have consequences greater than the actual risk.

The end result of this is that organizations often implement specific security controls because they are required by laws, regulations, or standards—not because their risk analysis would otherwise compel them to.

IT Management Practices

The primary services in the IT organization typically are development, operations, and support. These primary activities require the support of a second layer of activities that together support the delivery of primary IT services to the organization. The second layer of IT management practices consists of the following:

• Personnel management

• Sourcing

• Third-party service delivery management

• Change management

• Financial management

• Quality management

• Portfolio management

• Controls management

• Security management

• Performance and capacity management

Some of these activities the IT organization undertakes itself, while some are usually performed by other parts of the organization. For instance, most of the personnel management functions are typically carried out by a human resources department. This is another essential reason for the existence of an organization-wide IT steering committee that is represented by other departments such as human resources. This enables the entire spectrum of IT management to be centrally controlled even when other departments perform some IT management functions.

Personnel Management

Personnel management encompasses many activities related to the status of employment, training, and the acceptance and management of policy. These personnel management activities ensure that the individuals who are hired into the organization are suitably vetted, trained, and equipped to perform their functions. It is important that they are provided with the organization’s key policies so that their behavior and decisions will reflect the organization’s needs.

Hiring

The purpose of the employee hiring process is to ensure that the organization hires persons who are qualified to perform their stated job duties and that their personal, professional, and educational histories are appropriate. The hiring process includes several activities necessary to ensure that candidates being considered are suitable.

Background Verification Various studies suggest that 30 to 80 percent of employment candidates exaggerate their education and experience on their résumé, and some candidates commit outright fraud by providing false information about their education or prior positions. Because of this, employers need to perform their own background investigation on an employment candidate to obtain an independent assessment of the candidate’s true background.

Employers should examine the following parts of a candidate’s background prior to hiring:

• Employment background The employer should check at least two years back, although five to seven years is needed for mid- or senior-level personnel.

• Education background The employer should confirm whether the candidate has earned any of the degrees or diplomas listed on their résumé. There are many “diploma mills,” enterprises that will print a fake college diploma for a fee.

• Military service background If the candidate served in any branch of the military, then this must be verified to confirm whether the candidate served at all and whether they received relevant training and work experience, and whether their discharge was honorable or otherwise.

• Professional licenses and certifications If a position requires licenses or certifications, these need to be confirmed, including whether the candidate is in good standing with the organizations that manage those licenses and certifications.

• Criminal background The employer needs to investigate whether the candidate has a criminal record. In countries with a national criminal registry like the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) in the United States, this is simpler than in countries that have no nationwide criminal records database. Some industrialized countries do not permit criminal background checks, believe it or not.

• Credit background Where permitted by law, the employer may wish to examine a candidate’s credit and financial history. There are two principal reasons for this type of check: first, a good credit history indicates the candidate is responsible, while a poor credit history may be an indication of irresponsibility or poor choices (although in many cases a candidate’s credit background is not entirely his or her own doing); second, a candidate with excessive debt and a poor credit history may be considered a risk for embezzlement, fraud, or theft.

• Terrorist association Some employers wish to know whether a candidate has documented ties with terrorist organizations. In the United States, an employer can request verification of whether a candidate is on one of several lists of individuals and organizations with whom U.S. citizens are prohibited from doing business. Lists are maintained by the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), a department of the U.S. Treasury, and also by the U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security.

• References The employer may wish to contact two or more personal and professional references—people who know the candidate and will vouch for his or her background, work history, and character.

Employers also frequently research a candidate’s background through word-of-mouth inquiries, Internet searches, and social media. Much useful information can be obtained that can help an employer corroborate information provided by a candidate.

Background checks are a prudent business practice to identify and reduce risk. In many industries they are a common practice or even required by law. And in addition to performing a background check at the time of hire, many organizations perform them annually for employees in high-risk or high-value positions.

Employee Policy Manuals Sometimes known as an employee handbook, an employee policy manual is a formal statement of the terms of employment, facts about the organization, benefits, compensation, conduct, and other policies.

Employee handbooks are often the cornerstone of corporate policy. A thorough employee handbook usually will cover a wide swath of territory, including the following topics:

• Welcome This welcomes a new employee into the organization, often in an upbeat letter that makes the new employee glad to have joined the organization. This may also include a brief history of the organization.

• Policies These are the most important policies in the organization, which include security, privacy, code of conduct (ethics), and acceptable use of resources. In the United States and other countries, the handbook may also include antiharassment and other workplace behavior policies.

• Compensation This describes when and how employees are compensated.

• Benefits This describes company benefit programs.