2.3

OIL

Oil, or petroleum, is a liquid fossil fuel formed when decaying plant life becomes trapped in a layer of porous rock. After millions of years, heat and pressure convert decaying plant life into hydrocarbons. Some of these hydrocarbons are gases, others are solids, and still others are liquids. Petroleum is the generic name for any hydrocarbon that is liquid under normal temperature and pressure conditions.1 Like other fossil fuels, the mixture of hydrocarbons in petroleum can vary widely. When petroleum is first extracted from the ground, it is called crude oil.

It can be dangerous to burn crude oil directly since the lighter portions of it can form explosive vapors and the heavier portions may not flow easily or ignite smoothly. As a result, crude oil is usually separated into components that are more uniform in composition. This separation is done in a refinery through the process of distillation. After crude oil is distilled, there are specific names for each liquid that is produced (gasoline, heating oil, etc.). The term petroleum refers to crude oil and all of the products refined from it.

The liquid properties and high energy density of petroleum make it a popular fuel for vehicles. Compared to hydrocarbon gases like methane or propane, petroleum contains a lot of energy per unit of volume. For example, a tank of a hydrocarbon gas, like propane, will only fuel a backyard grill for a couple of hours. However, the same volume of gasoline will be sufficient to drive a car for several hundred miles. Additionally, compared to solid hydrocarbons like coal, liquids are much easier to move around inside an engine.

Crude oil is the single most traded commodity in the world. As a result, the global importance of oil is far greater than its impact on just the energy industry. Because of the global high profile of crude oil trading, the oil industry is subject to a very high level of international scrutiny. It is often viewed as a benchmark for the energy sector, and can have a disproportionate impact on electricity and heating costs.

Crude Oil Market Participants

The trading of crude oil is dominated by the relationship between the suppliers and consumers. The largest importers of crude oil are the industrialized nations of North America, Europe, and the Asia-Pacific region. The major net exporters are less developed countries in the Middle East and South America. Transportation and storage costs are the primary determinant of where supplies originate and where they end up. All things being equal, oil is transported to the nearest market first. If that market is sufficiently supplied with oil, then the next closest market is chosen.

International politics and environmental regulations also affect the flow of petroleum. Sometimes, countries will refuse to buy or sell oil to one another. For example, in 1973, OPEC2 countries refused to sell oil to Western Europe, America, and Japan because of their support for Israel. Another example of oil not going to the nearest market is due to environmental regulations. The United States requires that gasoline and diesel contain very low quantities of sulfur. Sulfur is a major pollutant and source of acid rain. Compared to countries that don’t have those restrictions, low sulfur crude oil is more valuable in the United States. This makes it worthwhile to ship low sulfur oil long distances to get to that market.

There are five major types of participants in the petroleum market—producers, refiners, marketers, governments, and consumers.

Producers. Oil is produced around the world. About half the world’s supply of crude oil is located in the Middle East. Since the region has a relatively low population and a low demand for oil, it is the single largest exporting region. There are many other oil-producing regions worldwide. Several industrialized countries, like the United States, are major oil producers. However, industrialized countries tend to be net importers of oil due their high domestic demand.

Refiners. Refiners convert crude oil into finished products. These facilities are most commonly located near the consumer markets. The net profit of a refiner is proportional to the region’s crack spread—the profit from buying a barrel of oil, splitting it into its components, and selling the components. Refiners typically try to eliminate their exposure to petroleum prices.

Marketers. Marketers buy petroleum products with an intention of reselling those products. These organizations can be anything from a hedge fund to a gas station operator. Typically, marketers will try to buy finished products and resell the same product at a higher price.

Governments. Outside the United States, most country governments will own the mineral rights to petroleum. In addition, governments can pass rules around trading, create consumer protection standards, use crude oil as a political tool, and can seize, or nationalize, the assets of producers and refiners.

Consumers. The end-users of petroleum products are consumers. Consumers run the range from industrial manufacturers to private individuals filling up their cars with gasoline.

Exploration and Drilling

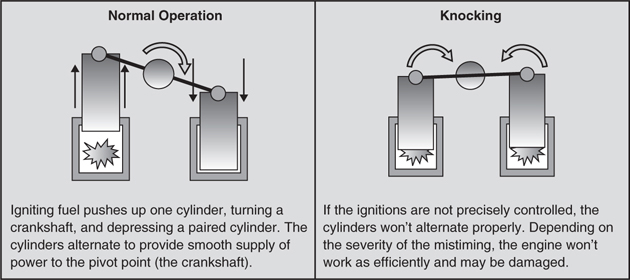

Oil, like other fossil fuels, is formed when decaying organic material is trapped underground. Commonly, liquid and gas hydrocarbons are found in the same area. Both liquid and gas hydrocarbons (petroleum and natural gas) are lighter than rock and will naturally migrate upward unless that movement is prevented by a layer of impermeable rock. This combination of an impermeable layer of rock overtop a permeable layer of rock is called a trap (Figure 2.3.1). Oil exploration involves looking for traps in areas likely to contain oil or gas.

Figure 2.3.1 An oil trap

The most common way to search for oil traps is to use seismology. Seismology is the study of how energy waves, like sound waves or earthquakes pass through the Earth’s surface. Different types of rock transmit energy at different speeds. Engineers can determine the type of rock layers in an area by creating sound waves and sending them into the Earth. Some of the sound will echo back toward the engineers. The timing of how quickly the sound returns and its strength will give a good indication of the type of rock layers and their relative depths. However, seismology is not an exact science. Even if seismologists know that a liquid is trapped, they might still need to dig a well to determine the exact nature of the liquid.

Crude Oil

Crude oil is the single most traded commodity in the world. Because of this, crude oil trading is highly influential and crude oil is viewed as a benchmark for the entire energy market. Despite having no real connection to many other energy commodities, crude oil prices often have a large impact on other energy markets.

There are many different types of crude oil. To distinguish types, crude oil will often be referred to as sweet or sour. These terms describe the percentage of a major pollutant, sulfur. During combustion, sulfur combines with oxygen to form sulfur oxides. In the presence of water (another byproduct of combustion), sulfur oxides form sulfuric acid. Crude oil with less than 0.5 percent sulfur is considered “sweet.” Crude oil with a sulfur content of more than 0.5 percent is typically classified as “sour.”

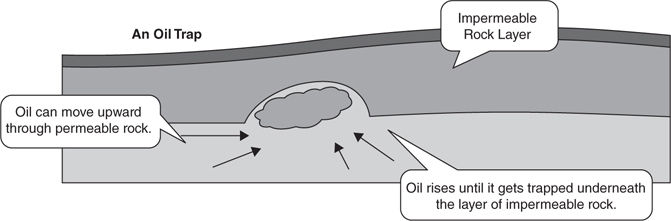

The terms light and heavy are also used to describe the density of crude oil. In general, less dense products like jet fuel and gasoline are more valuable than heavier products like heavy fuel oil and asphalt. As a result, crude oils that contain a higher proportion of lighter components will be more valuable than heavier crude oils. Density for petroleum products is classified by its API gravity. Higher API gravities are associated with less dense liquids. Liquids with an API gravity higher than 10 degrees will float on water, while liquids with an API gravity less than 10 degrees will sink. Light crude generally has an API gravity of 38 degrees or more. Heavy crude has an API gravity of 22 degrees or less. Crude with API gravity between 22 and 38 degrees is generally referred to as medium crude. Crude oils with an API gravity above 45 degrees are referred to as condensate. In general, light crudes are more valuable than heavier crudes or condensate (Figure 2.3.2).

Figure 2.3.2 American Petroleum Institute gravity

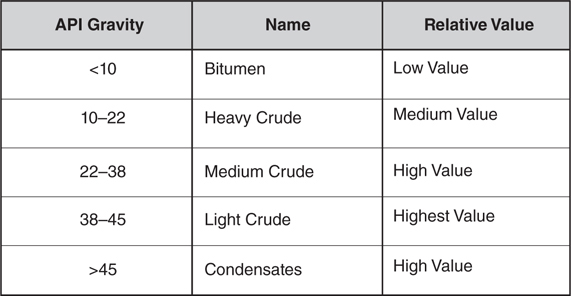

To an energy investor, the density of crude oil is important because in some parts of the world, like Europe, crude oil is typically traded by weight (metric tons, abbreviated MT or tonnes). In other parts of the world, like the United States, crude oil is traded by volume (barrels, abbreviated BBL). The denser a substance, the smaller the volume required for a given amount of weight. This means that conversion between units becomes an obstacle to investors (Figure 2.3.3).

Figure 2.3.3 Crude oil conversion factors

Transportation

Petroleum is typically transported as crude oil until it is close to its final destination. Only after it arrives close to the final location is the crude oil separated into its components. This business model is the result of several factors. The first factor is that refineries can cost billions of dollars to build and have expected life spans of more than 50 years. Because of that, a refinery will outlive almost any single oil field. The second factor is that oil fields are often located in remote areas of the world. A refinery needs a highly trained workforce, and it is much easier to find that workforce near major cities. A third factor is that refineries located near their customers can optimize their output to meet local demands and comply with local regulations. Finally, refineries also tend to be located where the safety of both workers and investors can be ensured. Placing a multibillion dollar investment in a safe location where it is unlikely to be damaged by violence or nationalized by an unfriendly government is an important consideration for a long-term investment.

After it is produced, crude oil will typically be transported through a pipeline to a port facility. Once it is at the port, it will be loaded onto a transport ship that will carry the crude oil to a refinery for processing. Larger ships are more cost effective at transporting crude oil. However, there are often physical constraints like the water depth at docking facilities or the width and depth of various canals (like the Suez Canal or the Panama Canal) that constrain the maximum size of ships. As a result, there are a variety of different crude oil transport ships (Figure 2.3.4).

Figure 2.3.4 Types of crude oil cargo vessels

Refining

Refined petroleum products are created by separating crude oil into various components. This process starts with simple distillation, where crude oil is separated into fractions by boiling it at progressively higher temperatures. Since each component of crude oil will boil at a slightly different temperature, slowly increasing the temperature of crude oil will cause products to progressively boil off. These gases are then trapped and cooled to bring them back into liquid form.

After the initial separation of products, many refiners continue to process the heavier fractions to increase their value. In general, lighter petroleum products, like gasoline and jet fuel, are more valuable than the heavier products, like asphalt. By splitting the heavier products (cracking them) into simpler products, their value is increased. Postdistillation processing (called downstream processing) also removes sulfur from the oil and is used to increase the octane of gasoline. Downstream processing can substantially alter the output of a refinery. For example, simple distillation might produce 20 percent of its output as gasoline. However, downstream processing can increase that percentage to around 50 percent. By cracking heavier products into less dense products, downstream processing typically converts a 42-gallon barrel of crude oil into approximately 45 gallons of finished products.

It is impossible to produce just one distilled product, like gasoline, without producing the others. The process of converting crude oil into gasoline involves creating every refined petroleum product at the same time. For example, if a refinery increases its output in response to higher gasoline prices, it runs the risk of glutting the market with its other refined products. The typical mix of refined products in a barrel of crude oil is shown in Figure 2.3.5.

Figure 2.3.5 Approximate mix of products from a 42-gallon (U.S.) barrel of crude oil

However, the actual products from a barrel of crude oil can vary substantially. Every barrel of crude oil contains a different mix of raw materials. Crude oil that converts into a high proportion of lighter products through simple distillation is called a premium crude. Premium crude oils are more expensive than lower quality crude oil. Other common terms for crude oil describe its viscosity and sulfur content. Light sweet crude oil pours easily and contains relatively low sulfur. Heavy sour crude has a thick, syrupy consistency and contains high levels of sulfur.

The process of distillation links the prices of refined petroleum products to crude oil prices. If the price of crude oil rises, all of the refined products will become more expensive. However, there is a different type of link between the prices of the refined products. If a gasoline shortage forces refiners to increase their gasoline production, the market will become flooded with other petroleum products. As a result, there is often a negative correlation between the prices of the refined products. The relationship between crude oil and distilled products is known as the crack spread.

Fractional Distillation

Crude oil is refined (separated into its component pieces) by fractional distillation. It is placed into a large vertical container, called a distillation tower, and heated (Figure 2.3.6). The lightest elements, with lowest boiling points, rise to the top while the heavier fractions settle at the bottom. By selectively siphoning off the lighter fractions, crude oil is separated into pieces.

Figure 2.3.6 A distillation tower

(Source: U.S. Energy Information Agency)

After crude oil is separated into its components by distillation, many of the heavier liquids are further processed by subjecting them to high temperatures and pressures. This process, called cracking, breaks the heavier liquids into lower density liquids.

Comparing Crude Oil to Refined Petroleum

While there is active trading in both crude oil and refined petroleum products like gasoline, the markets are very different from one another. Crude oil has a global market and is transported around the world. It is approximately the same product and price wherever it is being traded. For example, if the price of oil is higher in New York than Paris, tanker ships will be diverted from France and start heading to New York. The refineries in the northeastern United States and northern Europe can each accept crude oil intended for the other location.

Refined petroleum products, like gasoline, are typically regional markets. Prices and product formulations vary substantially between regions. Historically, it has been considered very risky to locate refineries outside the industrialized countries. As a result, finished products are refined close to their final destination. There is a limited international infrastructure for transporting finished petroleum products in bulk. There is some international trade in these products, but the volume of trading is much lower than for crude oil. Local environmental regulations further fragment the market for refined products. For example, gasoline used in North America is required to use a different formulation than gasoline used in Europe. This is true even on a national level. For example, gasoline in California might use a different formulation than gasoline in New York.

Gasoline

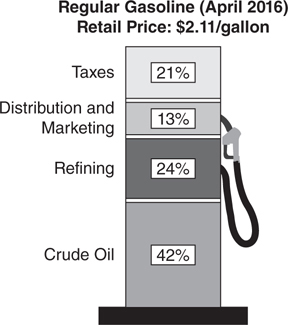

Gasoline is the primary fuel used to power automobiles and light trucks around the world. In 2007, it accounted for 44 percent of all petroleum consumption. In the United States, about two-thirds of the cost of gasoline is related to the cost of acquiring crude oil and refining it. Taxes, distribution, and marketing fees make up approximately one-third of the remaining cost (Figure 2.3.7). The demand for gasoline increases during periods of good weather. Demand starts to rise during the spring and peaks in the late summer.

Figure 2.3.7 The price of gasoline

(Source: U.S. Energy Information Agency)

The primary method for distributing gasoline is through pipelines. Pipelines transfer gasoline from refineries to terminals near consuming areas. At the local terminals, gasoline is mixed with additives, like ethanol, to meet local government regulations. Then, the gasoline is transported by tanker truck to local gas stations where it is sold to consumers. In the United States, gasoline is differentiated by its octane level and formulation. Along with local taxes, these factors account for most of the regional variation of gasoline prices. Other factors influencing the retail price of gasoline can include transportation costs and the marketing plan of the individual gas station owners.

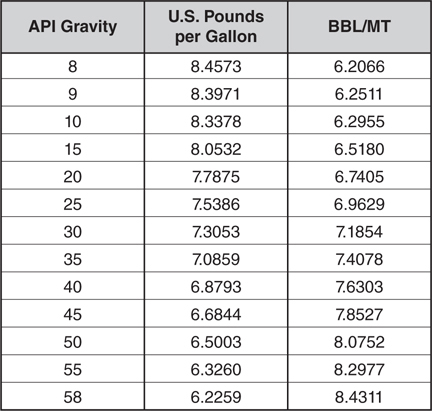

Octane is a measure of how much gasoline resists ignition. When gasoline resists ignition, less power is delivered to the power train of the car. Instead, it will be wasted as heat. Octane is not a measure of the energy in a tank of gasoline. For example, ethanol has a higher octane than gasoline (it is easier to ignite), but contains less energy. Adding ethanol to gasoline increases the octane of gasoline, but still decreases the total miles per gallon of the car using that gasoline.

The formulation of fuel refers to the various additives that are required or prohibited. For example, a state might mandate that all gasoline sold between March and October contains 10 percent ethanol. Sometimes additives are prohibited. For example, lead was once used as an antiknock agent in gasoline in the United States. Antiknock agents are used to increase the octane rating of gasoline. However, the lead pollution from automobile exhaust became a major health hazard and its use was later banned. Sulfur is another example of a regulated pollutant.

Gasoline prices fluctuate throughout the year based on crude oil prices, consumer demand, and formulation (Figure 2.3.8). As a general rule, gas prices tend to increase rapidly in the early spring and summer. Prices stabilize in the later summer and decline in the coldest winter months. Gasoline prices tend to be very volatile because there is a limited amount of supply that can be generated from refineries and consumers can’t substitute other fuels for gasoline.

Figure 2.3.8 The ratio of gasoline prices to crude oil prices

Diesel Fuel (Heating Oil)

Heating oil and diesel fuel are variations of the same product, a distillate of petroleum called No. 2 fuel oil. Of the two, diesel fuel typically has stricter requirements for a minimum pentane rating (similar to octane ratings on gasoline) and lower sulfur content. Otherwise, both chemically and in the financial markets, the two products are nearly identical and used interchangeably. Like gasoline, a large portion of the consumer price of diesel comes from taxes, distribution, and marketing expenses (Figure 2.3.10).

Figure 2.3.10 Cost of diesel fuel

About 80 percent of No. 2 fuel oil is used as diesel fuel. The remainder is used for residential and commercial heating. Nearly all large trucks, buses, trains, farm equipment, and large boats in the United States use diesel engines. The majority of diesel fuel is used for on-highway vehicles like semitrucks and tractor trailers.

There is a small international trading market for diesel fuel. Almost all of the diesel fuel that is used in the United States is produced domestically, with the surplus being shipped to other countries. Like most petroleum products, it is much more common for the raw materials (crude oil) to be traded internationally than the finished product.

When used as heating oil, the largest use for No. 2 fuel oil is for residential heating during winter months. In the United States, almost all of the houses that use oil heat are located in the northeastern portion of the country. As a result, heating oil prices are strongly influenced by winter temperatures in Mid-Atlantic and New England areas. Prices are lowest in summer months and spike during the winter (Figure 2.3.11). Households often try to reduce their oil costs by filling up their storage tanks during summer months when prices are low. However, since most households lack sufficient storage capacity to go an entire winter without refilling their supply, there is continued demand for heating oil throughout winter months. Most households will need to refill their heating oil four or five times a winter.

Figure 2.3.11 Ratio of diesel to crude oil prices

Oil Futures

Crude oil futures are the most traded contracts in the world. The two dominant international benchmarks for crude oil are the New York Mercantile Exchange West Texas Intermediate Crude (NYMEX WTI) and Intercontinental Exchange’s Brent Crude (ICE Brent) futures contracts. WTI generally represents the price for crude oil delivered in the southern United States. Brent represents the price of seaborne crude in the Atlantic Ocean. Both of these are crude oil that contains a high quantity of lighter petroleum components good for making gasoline, with low quantities of sulfur and other pollutants.

Each exchange will have a number of futures contracts associated with each commodity. These contracts differ based on their delivery date, with each contract delivering on a different date. The futures contract will often be described like “WTI December 2017” or abbreviated like CLZ7. In abbreviated form, the initial two characters are the abbreviation for the contract, the second to last character represents the month of delivery, and the final digit represents the year of delivery (Figure 2.3.12).

Figure 2.3.12 Futures month abbreviations

Each futures contract has a limited life span. This life span starts when the exchange allows trading and ends when the contract expires. Expiration occurs at a published date sometime before the delivery period. For example, a WTI contract might specify that futures shall cease trading on the third business day prior to the 25th calendar day of the month prior to delivery. This gives holders of futures contracts a chance to schedule their deliveries prior to the start of the delivery month.

Physical Trading

Because crude oil futures are so heavily traded, most physical crude oil transactions are based on the price of crude oil futures. This is different than how most other markets operate. For most other commodities, physical transactions determine a spot price—the amount of cash required to take possession of the commodity on the spot. That spot price then determines the price for future delivery. In the crude markets, just the opposite occurs, physical transactions are usually determined by prices observed in the crude oil futures.

A spot market contract is an agreement directly between two people, also known as a bilateral agreement, to buy or sell assets for immediate or short-term delivery. In theory, this exchanges cash and the commodity on the spot. In practice, spot market delivery for crude oil means sometime within the next four weeks.

In theory, the terms and conditions for physical crude oil trades can be customized for each transaction. In practice, the vast majority of spot trades follow standardized terms. This allows traders to avoid having the legal department individually negotiate contracts. Standard parts of these contracts include a definition of the volumes to be delivered each month, the delivery location, the approximate composition of the product (sometimes called the product grade), credit terms, payment terms, and some way to determine a fair price. Sometimes, the price will be fixed. In other cases, the price will be variable. The reason for using a variable price is to link transactions to the heavily traded futures market. That market is hard to manipulate and easy to hedge. Variable pricing normally includes the following:

• Index Price. A common index price is the next-to-deliver crude oil contract. This is also called the prompt contract.

• Grade Differential. The grade differential is a premium or discount to index depending on the type of crude grade. The term basis is sometimes used instead of differential.

• Location Differential. This is a premium or discount based on the cost to transport oil to the delivery location. For example, this might represent a pipeline and or trucking fee. The term basis is sometimes used instead of differential.

• Other Differential. Other differential may be a premium or discount based on negotiations.

The index price is typically specified using one of several formulas. One way to do this is to base the physical contract on a specific future. However, many crude oil contracts don’t expire at month end. As a result, a common approach is to use a calendar month average, or CMA, price.

A calendar month average price is based on the average price of the next to expire, or prompt, futures contract over a month. For example, if a January futures contract expires two-thirds of the way through December, the calendar month average price for December is based on the January contract for the first two-thirds of the month and then the February contract for the last one-third of the month.

Crack Spreads

Cracking refers to the process of separating out and transforming the components of crude oil into commercially saleable products. A crack spread is the difference between the price of finished petroleum products and the price of crude oil. Since most refined petroleum products are not exported internationally, crack spreads will vary substantially throughout the world. Each region will have its own crack spread set by the supply-and-demand considerations of its local market for finished petroleum products.

The crack spread is the wholesale price of refined petroleum products less the cost of raw materials. It is approximately equal to the profit that a refiner will earn by converting crude oil into refined petroleum products. If the spread between finished products and crude oil is too narrow to produce a refining profit, refiners will cut back on production until the prices of the finished products rise.

A typical trade in a crack spread would be to “buy” a future crack spread that is too small for refiners to make a profit and benefit when refiners cut back on production and prices rise. Buying a crack spread means the trader benefits from a rise in finished petroleum products and a fall in crude oil prices. Because the price in all of these products tends to move up and down together, a crack spread has limited exposure to the price of crude oil. Another variation of a petroleum spread trade might allow traders to speculate on the relationship between gasoline and heating oil.

Each region has a typical grade of crude oil that is used as a benchmark. In North America, West Texas Intermediate Crude (WTI Crude) is most common. In Europe, Brent Crude is used. For a crack trader, the different types of crude oil don’t just mean the prices vary slightly. Different crude oils vary in composition. Premium crude oils, like WTI Crude or Nigerian Bonny Light, will produce a higher percentage of the lightest gasoline-like products through distillation compared to less desirable crude oils. As a result, refiners have to optimize the mix of crude oil entering the refinery to produce the most profitable mix of refined products desired in their region. The typical mix of products produced by simple distillation of several crude oils is shown in Figure 2.3.13.

Figure 2.3.13 Yields from simple distillation

(Source: Courtesy of U.S. Energy Information Agency)

Refiners are natural traders of crack spreads. Crack spreads are a primary tool for refiners to hedge their output. Refiners face a substantial price risk between the time they buy crude oil and the time when they can sell their finished products. In most cases, refiners attempt to lock in their profits by agreeing to a sales price of their most important products ahead of time. They do this by trading financial contracts in crude oil, gasoline, and diesel/heating oil. Crack spreads also allow major users of refined products to lock in spreads without taking on a large exposure to crude oil prices.

Since the major oil products are all widely traded on exchanges, almost anyone can make crack trades. There is a very active market in crack trades. The most common spread trades are based on crude oil, gasoline [Reformulated Blendstock for Oxygen Blending (RBOB)], and diesel fuel (heating oil). The ratio between these three products defines the crack trade. Usually this ratio is abbreviated X:Y:Z, where X is the number of crude oil contracts, Y is the number of gasoline contracts, and Z is the number of diesel fuel contracts. The most common ratio is 3:2:1, but 2:1:1 and 5:3:2 ratios are also fairly common (Figure 2.3.14).

Figure 2.3.14 A 3-2-1 crack spread

Refiners benefit when refined products appreciate in price relative to crude oil. In other words, they are long the crack spread. Refiners can eliminate this exposure by selling a crack spread. Selling a crack spread (alternately, going short the crack spread) means the trader will benefit when the price of crude oil rises or the price of refined products declines.

Exchange Traded Spreads

Sometimes crack spreads are their own financial instrument. It is also possible to enter into a crack spread by trading futures in each of the underlying petroleum commodities. Every time a trader makes a futures trade on an exchange, the trader is required to post margin to ensure that he or she has enough money to meet his or her financial responsibilities. The amount of margin required is directly proportional to the risk of the trade. Entering into a crack spread by trading individual commodities can result in a substantial amount of capital being locked up in margin accounts. However, the combination of trades in a crack trade is much less risky than holding an outright position in any of the underlying commodities. As a result, less money is required up front to trade the spread as a single unit.

Exchanges commonly offer crack spread trading alongside markets for the underlying commodities. As a result, it is fairly common to talk about a “crack spread” as its own traded instrument. Moreover, it is often possible to buy “crack spread options” and “crack spread futures” on an exchange. The behavior of these contracts is identical to creating a crack spread through individual products. However, margin requirements are lower and all of the futures are traded simultaneously.

Ethanol

Ethanol is an alternative to petroleum fuels that can be produced by fermenting and distilling almost any starch-containing crop. It is a clear colorless liquid that is chemically identical to the alcohol found in intoxicating beverages. Ethanol intended as fuel is denatured to make it unsuitable for drinking because alcohol intended for human consumption is subject to a lot of government regulations. Ethanol is fairly easy to manufacture from common crops like corn or sugarcane. Ethanol is a renewable fuel source that produces fewer greenhouse emissions than fossil fuel.

On the downside, since fertilizer and farm equipment both require petroleum fuel and produce a lot of pollution, it is unclear if ethanol production actually reduces either petroleum demand or pollution. Ethanol also does not have the same energy density as gasoline. Because of this, the transportation of ethanol is relatively more expensive than gasoline transportation. Ethanol is also highly corrosive and absorbs water. As a result, engines and gasoline pipelines have to be specifically built or modified to handle ethanol.

Another drawback of ethanol is that it produces higher amounts of some types of ground level pollution than gasoline. For example, ethanol produces twice the ozone of a similar gasoline engine. Another criticism of ethanol is that it raises food prices. Ethanol is produced from crops that would otherwise be used as food. Given the limited amount of cropland in the world, using crops to produce ethanol means less food is available for a growing population.

Compared to gasoline, ethanol is an inferior fuel by most comparisons. The popularity of ethanol is a result of the expectation that the world will be running out of easily obtainable petroleum in the near future. Ethanol can be produced today in larger amounts than other alternative fuels, and much of the existing infrastructure for gasoline can be retrofitted to accept ethanol.

Starch is converted to ethanol through the process of fermentation. This is essentially the same process used to produce most alcoholic drinks. First, the raw materials are milled by grinding them into a fine powder called meal. Then, liquid is added to the meal to produce a slurry that is heated. Heating helps the meal dissolve into a liquid solution and kills any bacteria that might be present. Then, the mixture is cooled and enzymes are added to turn the starch into simpler sugars. After that, yeast is added into the mix. This yeast converts the sugars into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Finally, the alcohol is separated from any solids or liquids that may have formed during the fermentation process by distillation.

Biodiesel

Like ethanol, biodiesel is an alternative fuel that is receiving a lot of research attention.

Biodiesel is an alternative fuel for diesel engines created by removing glycerin from vegetable oils. Although biodiesel does not contain any petroleum, most diesel engines can use biodiesel without modification. Commonly, biodiesel is blended with petroleum diesel and the mixture is denoted “Bxx” where xx represents the percentage of biodiesel in the blend. For example B20 is 20 percent biodiesel.

There are some substantial advantages to using biodiesel. It is biodegradable, renewable, and generally produces lower emissions than standard diesel fuel. It is also nontoxic and, since it has a higher flashpoint than conventional diesel, is safer to transport and store.

On the downside, engines fueled by biodiesel have about a 10 percent reduction in fuel economy and power compared to burning diesel fuel. Biodiesel is also a stronger solvent than traditional diesel fuel. Very high percentages of biodiesel might require special engines. However, the biggest limitation of biodiesel is its cost. Currently, it can only be produced in limited amounts and is substantially more expensive than regular diesel fuel.

• B2–B5. B2 refers to a 2 percent biodiesel/98 percent diesel blend by volume. Similarly, B5 refers to a 5 percent biodiesel/95 percent diesel blend. Low-percentage biodiesel blends like B2 through B5 are popular fuels in the trucking industry because biodiesel has excellent lubricating properties. As a result, these blends can improve engine performance and lengthen an engine’s life span.

• B100. B100 is pure biodiesel. Pure biodiesel is a solvent that can loosen and dissolve sediments in storage tanks. It may also cause rubber and other components to fail in older vehicles.

• B99.9. B99.9 is biodiesel that has been blended with a small amount of diesel. Mixtures like this are done to take advantage of tax credits that some jurisdictions give to the blenders. Since B99.9 has already been blended, the blender would be paid the credit. As a result, buyers would not get the tax credit, and B99.9 would trade at a discount to B100.

Renewable Identification Numbers

In many countries, governments have passed renewable fuel standards to increase the amount of biofuels in the country. To track compliance with these programs, a biofuel like ethanol and biodiesel might be assigned an identification number when it is created. In many countries, these identification numbers, called renewable identification numbers (RINs), can be traded independently of the actual fuel. This allows the parties that are required to meet renewable fuel standards, typically oil refineries, the ability to purchase RINs to meet their compliance requirements.

1 Literally, petroleum means “rock oil” in Latin. It comes from the words petra, meaning “rock,” and oleum, meaning “oil.” Petroleum, coal, and natural gas are all hydrocarbon fossil fuels. They differ in that at room temperature, petroleum is a liquid, coal is a solid, and natural gas is a gas.

2 Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)—A major crude oil cartel consisting of the governments of 12 countries: Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela.