6.3

COUNTERPARTY CREDIT RISK

In addition to various types of price and model risks, energy traders are commonly exposed to the danger that their trading partners will be unable to fulfill their obligations. The energy market is full of agreements made directly between two counterparties. Assessing the ability of a trading partner to meet their contractual obligations is crucial to trading energy products.

There are two parts to examining credit risk—establishing the magnitude of the potential loss (the credit exposure) and the likelihood of a loss will occur (the credit quality). Getting this information correct is important to running an energy trading business. Firms will often have hard limits on how much exposure they can have to a single counterparty. If exposure estimates are too high, business will be hurt because trading will have to be curtailed. However, if the estimates are too low, there is a risk of catastrophic losses due to a trading partner not fulfilling its obligations.

Some common terms related to credit risk are:

• Obligor. A person who is obligated to do something required by law.

• Default. A failure to do something required by law—like paying off a debt.

• Counterparty. From the perspective of one participant, the counterparty is the other participant involved in a contract or transaction.

Credit Exposure

Credit exposure identifies how much money could be lost in the event of a default. At its simplest, calculating credit exposure assumes a complete loss on every contract. The size of the complete loss is called the exposure at default (EAD). This places an upper bound on the potential loss, but also tends to overestimate the severity of the loss because some of the lost money may be recovered through bankruptcy proceedings. The percentage of money recovered during bankruptcy is called the recovery rate. The percentage of money that is not recovered during bankruptcy is called the loss given default (LGD).

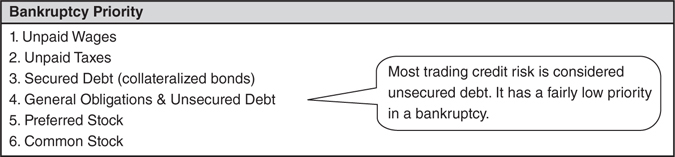

In a bankruptcy, there is a priority order that determines which creditors get paid first. This can have a large effect on credit exposure. Unfortunately, most trading obligations are unsecured debts and fairly low on the priority list. The first creditors to get paid are employees who are owed wages. Next, the company must pay any unpaid taxes. After that, the senior debt holders (typically the bondholders) get paid. After that, the trading partners (unsecured debt holders) are paid. The company’s stockholders have the lowest priority when it comes to getting repaid in a bankruptcy (Figure 6.3.1).

Figure 6.3.1 Bankruptcy priority

Credit Quality

Credit quality is the other aspect of modeling credit risk. It attempts to describe the probability that a firm will default on its payments. This usually needs to be a forward-looking measure since energy contracts commonly last several years. There are a number of ratings agencies that provide credit ratings. These ratings can be augmented by in-house research focusing on a couple of key counterparties. There can be several layers to this analysis—a trading partner’s credit risk will depend on the credit quality of its own clients. Also, a company is less likely to default if its large trades have moved in its favor, and it is more likely to default if trades have moved against it.

A good example of a cascading credit crisis was the bankruptcy of Enron. Enron was the single largest energy trader in the world. Enron was almost everyone’s largest trading partner. As a result, even companies that didn’t trade directly with Enron were exposed to its bankruptcy. When Enron went bankrupt, its assets were frozen. It stopped meeting its financial obligations. As a result, firms that traded with Enron had problems meeting their obligations, and so on. When Enron went bankrupt, the credit quality of many energy trading firms dropped at the same time.

Credit quality is often described by the term probability of default (PD). PD indicates the likelihood that the obligor will be unable to make scheduled repayments or similar obligations. When an obligor is unable to pay its debts, the obligor is said to be in default of the debt. Typically, this will lead to bankruptcy or similar proceedings where the creditors will seek partial repayment.

There are a number of ways to estimate probabilities of default. For something like a credit card portfolio, there will be enough defaults that direct observation is possible or a company, like Fair Isaac, may publish credit ratings (i.e., a person’s FICO score). However, trading portfolios typically have low default probabilities, making it difficult to directly observe default rates. An alternate way to estimate default probabilities is to use credit ratings. A second alternative for large counterparties, like international investment banks, is to look at the credit default swap (CDS) market. The CDS approach can only be used for counterparties who have traded CDS products. This limits the CDS approach to very large counterparties like oil majors and large banks.

Protecting Against Credit Risk

The most obvious way of avoiding credit risk is to know your trading partner. Before trading with someone, most energy trading firms will want to know something about that person or company. For example: What is their line of business? How many assets do they have? What is their business model?

A second way of limiting exposure is to limit the amount of credit that can be extended to a trading partner. Combining payments and receipts is a common way of limiting exposure. In this way, only the net exposure needs to be watched. Another way to limit credit exposure is to have a credit limit. A credit limit prevents additional trading when the net exposure to a trading partner gets too large.

A third way to limit credit exposure is to use collateral. Collateral is an asset that is used to guarantee performance of a financial obligation. Typically, collateral is held in trust until the financial obligation is resolved. The collateral remains the property of the person or company guaranteeing performance. It might be in the form of bonds, stocks, or other investments.

If a company doesn’t have the assets necessary for collateral, and is a fairly high credit risk, it might be required to buy insurance in the form of CDS. There is a trading market specific to CDSs where it is possible for a high-risk company to pay a low-risk company a fee to guarantee the payment of its obligations. This doesn’t eliminate credit risk completely, but it does mean a company with a good credit rating is backing the exposure.

A fourth way of limiting counterparty credit risk is to incorporate contractual terms that mitigate the effect of credit risk. Two of the most common contractual terms used to limit credit risk are cross-default clauses and master netting agreements. A cross-default clause is a contractual clause that prevents a trader from selectively defaulting on an obligation. If a borrower defaults on any obligation, all of its obligations are considered to be in default. A master netting agreement forces a bankruptcy court to combine the exposures from various trades and treat the offsetting exposures as a single exposure. Without this netting, a bankruptcy court will invalidate only the monies owed by the bankrupt party.

Ring Fencing and Structural Subordination

In the energy market, a major complication to knowing one’s trading partner is complex organizational structures. Many energy companies are actually conglomerates that are composed of multiple subsidiaries. The reason that many companies are conglomerates is that regulatory agencies (like public utility commissions) typically require that the companies that they regulate are protected from unregulated business.

Corporate structure affects investors because affiliates (subsidiaries of the same parent company) may or may not be liable for obligations made by other subsidiaries of the parent company.

In some cases, a holding company and all of its subsidiaries will cross-guarantee the debt and obligations throughout the entities. In these cases, there is no difference created by doing business and lending to one entity over another. This is the best situation from a credit risk perspective.

Another common structure is ring fencing. Ring fencing is an economic strategy that legally separates a regulated utility from its unregulated parent or holding company. Effectively, this makes the parent company a shareholder in the subsidiary rather than an owner. This is problematic because the parent company can’t directly access cash or assets located in the regulated utility. For example, they can’t sell off an unused generation plant to raise money for another business (Figure 6.3.2).

Figure 6.3.2 Ring fencing

When a subsidiary is ring fenced, the parent is entitled to dividends from the ring-fenced company and can sell off its ownership stake. However, the parent company often can’t increase the dividend for the regulated utility (this would usually require approval from the utility’s regulator) or liquidate the assets of the subsidiary to pay its own debts.

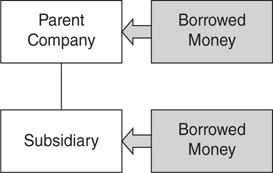

A second common organizational structure is structural subordination. This occurs when a conglomerate does business on several organizational levels (Figure 6.3.3). In the event that the company goes bankrupt, each subsidiary will pay its own creditors first. Only after that is done will money go to the parent company. This gives anyone with credit risk to the parent level a very low priority to get repaid using the assets owned by a subsidiary.

Figure 6.3.3 Structural subordination

Dangers of Limiting Credit Exposure

If credit controls are too strict, it is impossible to conduct an ongoing trading business. A trading firm wants to enter contracts that result in other people owing it money. That is the purpose of the trading company’s existence. From that regard, it is both impossible and undesirable to completely eliminate credit risk. Companies trade with other companies that want to do business with them. As a result, strict credit limits mean missed trading opportunities and damaged relationships. On the other hand, credit limits are essential to keep from being pulled into bankruptcy when another firm goes bankrupt or refuses to meet its obligation. Credit limits involve a balancing act between having no limits (and doing lots of business) and having limits (and possibly losing some profit).

Credit Risk, Valuation, and Financial Reporting

Accounting guidance specifies that credit adjustments need to be incorporated into financial reporting. The process for financial reporting is a bit different than risk management because both assets and liabilities need to be adjusted for reporting purposes.

• Credit Value Adjustment (CVA). An adjustment in the value of an asset owed to the reporting company reflecting the potential effect of counterparty default. This will lower the value of assets a company is owed by its counterparties.

• Debit Value Adjustment (DVA). An adjustment to a liability, similar to CVA, reflecting the reporting company’s own potential for default. This will lower the value of liabilities that a company owes its counterparties.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) Accounting Standards Convergence Topic 820 (ASC 820) is the accounting guidance that describes the relationship between fair value and credit adjustments. The credit guidance is discussed in Subtopic 10, Section 55, Paragraph 8:

55-8. A fair value measurement should include a risk premium reflecting the amount market participants would demand because of the risk (uncertainty) in the cash flows. Otherwise, the measurement would not faithfully represent fair value. In some cases, determining the appropriate risk premium might be difficult. However, the degree of difficulty alone is not a sufficient basis on which to exclude a risk adjustment. (FASB, 2009)

Both CVA and DVA are based on the concept of value as the liquidation cost of an investment. Liquidation cost is the amount of money that must be paid or received to transfer an asset or liability to another market participant. With a DVA adjustment, there is the possibility that if a company might be going into bankruptcy, a creditor might accept less than full value for monies that it might be owed in exchange for getting that money before bankruptcy proceedings.

To calculate CVA or DVA, it is necessary to calculate the expected loss of an investment. This can be found by multiplying the exposure at each payment date by the PD on that date multiplied by the percent of money lost if a default occurs (Figure 6.3.4).

Figure 6.3.4 Expected loss calculation