1.2

TRADING MARKETS

Trading means buying, selling, and exchanging commodities, products, and services. Not all energy markets are trading markets. Sometimes it is possible to buy a commodity, like gasoline at a service station, and not be able to resell it. The difference between a cash market and a trading market is that it is possible to both buy and sell in a trading market.

The most important commodities in the energy market are crude oil, natural gas, and electricity. Additional energy commodities are refined petroleum products like gasoline, alternative fuels like ethanol, pollution, weather derivatives, and carbon emissions. All of these products are related to the generation of either heat or electricity. Electricity and heat cannot be easily stored or transported. In most cases, arrangements to store or transport energy have to be made in advance. Because of this, it is difficult to trade most physical energy commodities on short notice. As a result, energy trading primarily consists of buying and selling agreements to deliver power at some point in the future. The time and location where the energy needs to be delivered is a key component in these agreements.

In most financial markets, the price for future delivery is closely related to the price for immediate delivery. However, in the energy market, this relationship works differently. In most financial markets, it is possible to buy the product today, hold the traded product for a while, and be able to resell the product in the future. Because of this relationship, it is feasible to react to expectations of future prices by trading for immediate delivery. Energy is different. If physical electricity is purchased the current day, it is usually necessary to use it immediately.

By itself, energy isn’t intrinsically valuable. Heat to warm a house is only valuable in the right place and time. In the summer, for example, home heating isn’t valuable at all. Quite the opposite is true. In hot weather, people pay money to remove heat from their homes. Likewise, if an extremely cold winter in Chicago causes natural gas prices to skyrocket, owning undeliverable gas somewhere else isn’t very valuable. Only the natural gas that can actually be delivered to customers in Chicago will be worth the high prices. The spot prices in Chicago don’t reflect expectations of future prices. Customers need heating immediately and can’t put off their purchase until prices are cheaper in six months. Nor can all of Chicago relocate overnight to an area with more natural gas supply or warmer weather.

Spot and Forward Markets

The spot market is a market where commodities are delivered immediately. Given the complexity of delivering some energy commodities, this means sometime between the next five seconds and next month. Spot transactions are usually consumers purchasing small quantities of a commodity for immediate use. The forward market is a financial market where delivery is scheduled at some agreed upon point in the future. Typically, forward markets schedule deliveries at least a month ahead of time.

Spot Market

The spot market, also called the cash market, is the market for instantaneous delivery of a commodity. The spot market gets its name because the transaction is done on the spot. This is the market with which ordinary people are most familiar. Trades in the spot market involve the physical transfer of an agreed on quantity of a standardized product for a specific price. Buying a meal at a fast-food restaurant is an example of a spot market transaction—the buyer gets immediate delivery of a standardized product for a set price. Another example of a spot transaction occurs when a light switch is turned on. The owner of the light switch buys electricity and immediately takes delivery of the product. Trading in the electricity spot market is restricted to people who can either deliver or use power immediately.

The spot market for energy is complicated by the fact that producers don’t know what the actual energy demand will be ahead of time. Consumers can turn on electrical devices and set the thermostats whenever they want. It is left to the local electric utility to cope with meeting that demand. When someone turns on a light switch, power needs to be immediately provided. It isn’t possible to substitute another type of power either—when a homeowner in New York turns on a light, the power company has to provide power in New York. Providing power somewhere nearby, like New Jersey or Connecticut, won’t meet the New York demand.

Because of the inability to transfer energy products without preparation, there are a large number of local spot markets. Each spot market can have its own rules and regulations. The prices in each spot market are determined by local supply and demand. As a result, since supply has to be arranged ahead of time, spot prices can be extremely volatile. It is easy for an unexpected change in demand to lead to either a shortage or glut in local supplies.

For related reasons, high spot prices in one area don’t necessarily mean that nearby prices will also be high. It is very possible that one region can have a surplus of power and another region a shortage when real-time transfers between the two markets are impossible. For example, if a power plant in California unexpectedly needs to go offline, prices there will spike upward as inefficient, expensive backup generators are turned on. A nearby power market, like Oregon, might not see any price change—that market might still have a sufficient supply of power to meet local demand.

The high price volatility in the local spot markets and the lack of correlation between adjoining regions tends to disappear in the forward market. While there is still time to arrange transfers of power or line up fuel supplies, prices tend to be based on macroeconomics. For example, if a power plant outage is expected in six months, there is probably time to arrange more cost-effective backup generation rather than relying on units that can be brought up to speed immediately.

Local regulation is another feature of the spot markets. Every municipality can have specific rules governing the physical delivery of power within their boundaries. Some markets might have prices set by government legislation while other markets might be open to competitive prices. Spot markets subject to heavy government regulation are called regulated markets. Most regulated markets are controlled by a government-sponsored monopoly that is overseen by a government commission; there is relatively little trading in these markets. Markets with competitive pricing systems are called deregulated markets. Deregulated markets were largely designed to encourage trading.

Forward Markets

Forward trading markets allow buyers and sellers to agree on transactions ahead of time. For physical contracts, this gives both sides sufficient time to prepare for delivery or receipt of a physical commodity. For example, a trader might agree to deliver 500 MMBtus of natural gas at Henry Hub three months in the future at a price of $8.12 per MMBtu.

Trades in the forward market are generally specified by several factors:

• Underlying Instrument. The commodity being traded, usually with a description of minimum quality standards that must be met. Often, this is just called the underlying.

• Quantity. The amount of the commodity that must be delivered.

• Delivery Price. The price per unit due at delivery.

• Delivery Date. The date at which the underlying instrument will be delivered.

• Delivery Location. The location at which the underlying instrument will be delivered.

From an economic perspective, allowing buyers and sellers to negotiate trades ahead of time reduces the volatility of energy prices. Energy is hard to store and transport. Giving large producers and consumers the opportunity to line up trading partners ahead of time reduces the uncertainty caused by short-term imbalances between supply and demand.

Trading, meaning the buying and reselling of assets, occurs almost exclusively in the forward market. The exceptions to this are cases where a trader has the ability to immediately deliver the physical asset or where he can buy a physical asset and relocate or store it.

Physical and Financial Settlement

Not everyone has the desire or capability to taking physical delivery. Historically, less than 1 percent of futures contracts go to physical delivery. The remainder of the contracts are liquidated prior to being exercised.

For example, if a trucking company wants to reduce its exposure to diesel fuel prices, it might buy crude oil contracts since the price of diesel fuel is correlated to the price of crude oil. That way, if the oil/diesel relationship continues to hold and the price of diesel fuel rises, the trucking company will offset its increased fuel costs with a profit on its investment. Of course, if the price of fuel falls, the savings to the trucking company would be largely eaten up by losses in the forward contracts. Essentially, the trucking company is attempting to lock in fuel costs. However, regardless of what happens to prices, the trucking company doesn’t want to take receipt of a lot of crude oil. It only wants the financial exposure.

When energy contracts are closed out in cash prior to delivery, this is called a financial settlement. When the trade is closed out by physically transferring a commodity, it is called a physical delivery. When a contract is closed out, the two counterparties to the trade essentially enter into a new trade that offsets the original trade. With a financial settlement of a trade, the two counterparties settle the difference in prices in cash.

FINANCIAL INSTRUMENTS

Trading is largely focused around the buying and selling of special types of contracts, called financial instruments or securities. The three main types of financial instruments are real assets, financial assets, and derivatives. Real assets include physical commodities (like crude oil, electricity, and gold) as well as legislatively created rights (like carbon emissions rights). Financial assets are primarily composed of contracts that give an ownership interest in a company (stocks), a lien on a company (bonds), or currencies. Derivatives are financial contracts that derive their value from other financial instruments. The vast majority of all energy transactions are derivatives (Figure 1.2.2).

Figure 1.2.2 Types of financial instruments

To be a financial instrument, assets need to be tradable. Tradable means that an asset can be legally assigned to someone else for a cash payment. It also means that it is possible to both buy and sell the financial instrument without giving up a substantial amount of the asset’s value. For example, it is generally possible to buy a cheeseburger (a standardized commodity) anywhere in the world. However, it may not be legal to resell the cheeseburger if selling food requires a license. Additionally, a typical benchmark for “giving up substantial value” is 10 percent of the value of the asset. Avoiding a 10% loss might not be possible in the cheeseburger resale market.

For an asset to be tradable, it also needs to be interchangeable with other assets of the same type. Otherwise, there will typically be some subjective value assigned to the asset. For example, a unique piece of framed art might be sellable. However, the value of the art and the time frame needed to arrange a sale would depend on the unique characteristics of the art. When assets are interchangeable with other assets of the same type, they are said to be fungible. In the example, the framed art is a nonfungible asset because it is not interchangeable with other art. Some other examples of nonfungible assets are property and intellectual property such as patents.

Additionally, it is necessary to consider how much time will be needed to convert the asset into cash or vice versa. This is called the liquidity of the asset. A liquid market allows an asset to be easily converted into cash, or a liability to be removed by paying cash, without a significant loss of money. Typically, liquid markets have low transaction costs and low volatility, and it is easy to execute a trade at a favorable price. An illiquid market does not allow easy trading. Typically, an illiquid market requires the trader to spend a substantial amount of time finding a trading partner or to take an unfavorable price.

Real Assets

Real assets are properties that have value due to their substance or physical attributes. In the energy markets, many real assets are tangible—they can be touched and manipulated. For example, oil, land, drilling equipment, refineries, power lines, and power generation facilities are tangible real assets. There are some real assets that don’t have physical form. These are less commonly found in energy markets and are called intangible assets. Some examples of intangible real assets are patents, advertising trademarks, and works of art.

Real assets are traded in spot markets. Due to the complexity in storing and transporting physical products, the trading market for real assets is limited. Real asset transactions tend to be one-directional—a buyer will purchase from a seller to use the asset, not to resell the asset. Most commodity trading is actually done in the derivatives markets discussed below.

Financial Assets

Financial assets represent ownership of real assets or cash flows created by real assets. The primary difference between financial assets and real assets is that financial assets are created by issuers. The two most common types of financial assets are stocks and bonds. These are important markets, but not the focus of this book.

• Stocks. A stock is a financial instrument that provides an ownership share in a company.

• Bonds. A bond is a debt investment (a loan to a company) that the company has to be repay after a fixed amount of time along with any accrued interest.

Derivatives

In the energy market, the most commonly traded type of financial instruments is a derivative. A derivative is a financial contract whose value is based on the value of some other asset. Some common types of derivatives are futures, forwards, swaps, and option contracts. For example, a contract to buy crude oil in the future is a derivative since it is a contract whose value is based on a real asset. If a crude oil contract is traded, only the contract and its associated obligations are transferred—the crude oil does not change hands at that time. The crude oil is only delivered when the contract is exercised.

The value of a derivative is the price where someone is willing to transfer a piece of paper (a contract) to someone else. In other words, trading markets are largely composed of people transferring obligations to do things in the future rather than transferring physical commodities.

From a terminology perspective, the asset that determines that value of the derivative is called an underlying asset. Commonly, this underlying asset is a real asset like crude oil or electricity. However, derivatives can also be based on other derivatives. For example, it is possible to buy an option on a forward contract.

Derivatives are defined by accounting guidance and have several important features:

• The underlying asset in a derivative transaction needs to be liquid and tradable.

• A derivative is created by an agreement between the buyer and seller. This agreement forms a legally binding contract and the price of the derivative is the money that would need to be paid or received to transfer the contract to another person.

• A derivative will not create wealth. It will only transfer wealth between buyer and seller or vice versa (this is called a payoff). Because of this, derivatives need both a buyer and a seller.

• Derivatives have a limited life span. At some point, the derivative will expire. Usually this triggers the transfer of wealth or physical assets between the buyer and seller.

• The amount of wealth transferred, and the direction of the transfer, will usually depend on something that hasn’t occurred at the time that the derivative was created. The derivative contract will state the rules for determining this quantity.

First, to be considered a derivative, the underlying asset in a contract has to be tradable. The accounting term that means tradable is readily convertible to cash (RCC). This means that it must be possible to both buy and sell the asset in a reasonable amount of time without losing more than 10 percent of the value in transaction costs.

A second feature of derivatives is that they are created by trading. This means that two parties (usually a buyer and a seller) are required to create a derivative. To create a derivative, the buyer and seller sign a written contract agreeing to transfer money between themselves. The profit made by one has to be paid by the other. A written contract between the two defines all of the terms of their agreement. Also, in some cases, the terms buyer and seller don’t really describe the relationship between the two traders. If that happens, the two traders are typically referred to as “Party A” and “Party B.” Either way, the obligations of the traders are fully described in the contract.

The price of a derivative is the cost to transfer the contract to another person. If the contract benefits the holder, then it is an asset and the owner would expect to get paid. If the contract does not benefit the holder, then it is a liability and the owner would have to pay someone to be free of the contract. Derivatives can fluctuate between being assets and liabilities. Quite often, derivatives are initially created at zero value.

Another feature of derivatives is that they have a limited life span. When a buyer and seller agree to the contract, they have to determine when they will need to fulfill their obligations to one another. The date that the obligations are finalized is called the expiration date or expiry. Shortly after that date, the buyer and seller will settle their obligations by paying cash or physically transferring the underlying commodity.

Finally, derivatives require some way to determine the relative obligations of the buyer and seller. This will be contractually agreed to in the contract in terms of fixed quantity of the underlying asset, known as the notional quantity, and price of the underlying.

TRADES AND POSITIONS

The process of completing a transaction is called executing a trade. After a trader executes a trade, the trader has a position in the commodity. A trade is a transaction; a position is the net exposure that results from one or more trades. For example, if a trader makes three transactions to buy crude oil, and one transaction to sell, the combination of all of those trades is known as a position. Positions are described by the terms long and short. When the trader benefits from a rise in the price of the commodity, he is said to have a long position. If the trader will benefit from a fall in the price of a commodity, he is said to have a short position.

Since trading typically involves the purchase and sale of contracts rather than physical commodity, different terms are used to distinguish between the trade and the result of the trade. For example, a trader might acquire a contract that requires the trader to sell something at a fixed price. If that sales price is above the prevailing market price, the contract would be an asset and would cost money to acquire. Conversely, if the sales price is below market, the contract would be a liability, and a trader would be paid money to acquire it.

A long position benefits from an increase in prices. For example, if a gasoline/crude oil spread is defined as the price of gasoline minus the price of oil, a long spread will benefit from a rise in gasoline prices or a fall in oil prices. In other words, the trader is long when he benefits from the spread growing larger. Long positions are commonly associated with owning an asset or agreeing to buy at a fixed price in the future.

A short position will benefit from a decrease in the value of the underlying. For example, a trader will be short crude oil if he has agreed to sell it to someone at a fixed price. The selling price is set, and the cheaper that the trader can obtain a supply, the greater the profit. As a result, the trader benefits from a fall in the price of crude oil. A short position is commonly associated with agreeing to sell a commodity at a fixed price in the future.

A trader can liquidate or close out a transaction by entering into an offsetting trade. Closing out a contract means to have no further risk or responsibility. In other words, closing out a trade means converting all positions to a liquid asset (cash).

A flat position is a combination of trades that is not affected by price movements. Quite commonly, it is impossible to close out a contract. For example, if the trade was a direct contractual agreement between two parties, both parties need to agree to dissolve the agreement. If a trader negotiated contracts to buy natural gas directly from one party and sold it to another, the trader is not necessarily free of his contractual obligations. The trader would still need to arrange receipt of the commodity from the first party and delivery to the second.

Finally, trades require both a buyer and a seller. These are called the parties to the transaction. From the perspective of each trader, the counterparty is the other trader involved in the transaction.

BILATERAL, OVER THE COUNTER, AND EXCHANGE TRADING

There are two ways for energy products to be traded. It is possible for trades to be made directly between two parties or through an intermediary called an exchange. When trades are made directly between two counterparties, they are called bilateral or over the counter (OTC) transactions. When trades are made through an exchange, they are called exchange-traded transactions.

Bilateral and OTC Trades

Bilateral trades are direct contractual agreements between two parties. These trades involve signing a contract, or extending an existing contract, each and every time a trade is made. Like any other contract that two people might sign, traders depend on the creditworthiness and reliability of the other party. If one party goes bankrupt, there usually is no immediate recourse except to attend bankruptcy proceedings. It can also be difficult to get out of a contractual agreement since both sides need to agree to modifications to the contract. An OTC trade is a type of bilateral agreement between a professional trading organization and a counterparty. The terms bilateral and OTC trading are largely interchangeable.

To simplify trading and contract negotiations, most bilateral agreements are based on a standard agreement produced by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). The most important feature of ISDA agreements is that all agreements between two parties made under an ISDA agreement form a single contract. This is important in bankruptcy cases because the credit risk under ISDA contracts is limited to the net amount of all contracts. For example, SolidGoldPower Inc. might have an agreement with Unreliable Corp. to receive 10 million MMBtus of natural gas and deliver 1 million MW/hours of power. If Unreliable Corporation went bankrupt and the trades were not combined into a single contract, Unreliable Corporation’s liabilities (its delivery of natural gas to SolidGoldPower Inc.) would be frozen by the bankruptcy court, but SolidGoldPower Inc. would still be required to deliver power to Unreliable Corporation. This would be disastrous to SolidGoldPower Inc. It would need to find another supplier of natural gas, pay the costs to arrange last-minute delivery, and then give all of its electrical output to Unreliable Corporation. When the contracts are netted, Unreliable Corporation is required to deliver the natural gas if it wants to receive the electricity because it can’t selectively freeze line items in a contract.

Companies with weaker credit will often need to offer collateral or insure their credit quality in order to convince others to trade with them. Collateral is money pledged as security. Credit-default swaps (CDSs) provide insurance against contractual defaults. A CDS allows a party with poor credit quality to buy insurance from someone with better credit quality. Essentially, this swaps the credit quality of the poor credit risk for someone with higher credit risk. It is important to note that CDS trades do not completely eliminate credit risk. There is still the possibility that neither the CDS buyer nor the issuer of the CDS will be able to meet their obligations.

Some of the major downsides of OTC agreements are the credit risk, contractual paperwork, and difficulty in initiating and liquidating trades.

Exchanges

Because of the difficulties associated with direct contracts, the number of people who can enter into OTC trades is often very limited. To make the markets more accessible to a wider audience, trading is often done on an exchange. Exchanges act as an intermediary where both sides of a trade agree to a transaction, but instead of transacting with one another, they enter into agreements with the exchange. This eliminates the counterparty risk associated with directly trading with a counterparty and makes it easier to buy and sell contracts.

For example, if a small hedge fund, GetRichNow Partners, wants to purchase a financial electricity contract in the OTC market, it would need to sign an ISDA agreement with all of its potential trading partners before entering into any trades. It would be an overwhelming job to sign agreements with every other small hedge fund on the speculation that someday a trade might occur. This would make it very difficult for the hedge fund to carry on its business of trading quickly.

With an exchange, much of that paperwork can be eliminated. Everyone who wants to trade can sign a single agreement with the exchange. This also allows traders to monitor the credit risk of a single counterparty, the exchange, for potential risk exposures. Even better, since exchanges are required to have solid financial backing for their commitments and can protect themselves by requiring that every trader submits a good-faith deposit, called margin, they are generally a very safe counterparty.

Exchanges make it much easier to enter and exit trades and allow anonymous trading. Entering and exiting a trade doesn’t leave any residual credit risk to other people. Additionally, since all trades are made with the exchange, it isn’t necessary to know the financial details of other traders or have them know your details. It is even possible to transact anonymously using a broker. The trades will be reported with the broker’s ID rather than the trader. Only the broker will know who initiated the trade.

The primary limitation on exchanges is that they can’t offer a lot of choices for contracts. To appeal to a large audience, contracts have to be standardized. Typically, there will only be a couple of contracts on each commodity. For example, all NYMEX natural gas contracts specify delivery at the Henry Hub in south-central Louisiana. This means that while there is a large liquid market for the Henry Hub contract, arranging for delivery in New York City isn’t so easy.

In practice, traders tend to use exchange-traded contracts as much as possible. For things they can’t do on an exchange, they will then try to arrange OTC trades.

Finally, it is important to note that while the exchange is the counterparty for every transaction, it is just matching up buyers and sellers. The exchange is only taking on the credit risk of each trade and not acting as a principal. The exchange protects itself by requiring traders to deposit good-faith deposits called margin. As a result, there will always be an equal number of buyers and sellers for each exchange-traded contract. Margin is described later in the chapter.

TYPES OF FINANCIAL INSTRUMENTS

Cash Transactions, Futures, Swaps, and Forwards

The four most common types of energy trades are cash transactions, futures, swaps, and forwards. Cash (or spot) transactions are an exchange of a physical commodity for cash in the spot market. Futures, swaps, and forwards are all contracts to buy an asset at a future date at a pre-arranged price. Futures are traded on an exchange. Swaps are financially settled contracts traded over the counter. Forwards are physically settled contracts traded over the counter. These contracts are similar, but have different names because of the substantial differences between OTC and exchange-traded markets.

• Cash Transactions (Spot Transactions). A cash, or spot, transaction is an exchange of cash for immediate delivery of a commodity. The definition of immediate varies by commodity—with oil it might mean within the current month while with natural gas it might be within the day.

• Futures. A future is a standardized commodity contract traded on an exchange. Futures will typically require traders to post a good-faith deposit, called margin, to transact. Futures will also result in physical delivery of a commodity if the contract is held until the expiration date.

• Commodity Swaps. A commodity swap is a futures or forward contract where the payment is settled in cash rather than physical delivery. In other financial markets, like the bond market, the term swap may refer to very different products, but in the energy markets swaps are financially settled contracts.

• Forwards. A forward is similar to a futures contract except that it is negotiated directly between two traders rather than being transacted on an exchange. Theoretically, because they are individually negotiated, forwards can be more customized than futures. In practice, forwards are nearly as standardized. Like futures contracts, forwards involve physical delivery.

Futures, forwards, and commodity swaps all have many features in common. They are all financial contracts between two parties to buy or sell a specific amount of a commodity for a fixed price (the strike price) at some point in the future (the expiration date). Other than a refundable good-faith deposit (called margin), these contracts don’t cost any money up front.

Futures

Futures are highly standardized contracts traded on an exchange. They have a limited number of product grades, delivery locations, and delivery times. The commodity must be delivered at the time specified by the exchange, in the location specified by the exchange, and at the quality level (grade) specified by the exchange. The possible permutations of these factors are very limited. Additionally, when futures settle, the counterparty for the delivery will be chosen by a clearinghouse. Exchange rules will determine how the buyers and sellers are matched up.

When transacting on an exchange, traders can submit instructions indicating their willingness to buy and sell. The exchange will then consolidate all of these orders into a trading book. Whenever there is an overlap between the prices where someone is willing to buy and the prices where someone else is willing to sell, a transaction will occur. Throughout this process, the buyer and seller don’t know the identity of one another. After the transaction, the exchange will serve as the counterparty for each trader (Figure 1.2.3).

Figure 1.2.3 An exchange

By acting as an intermediary, the exchange takes on the obligation for the trade should one of the traders not fulfill their obligations. To minimize this risk, exchanges will require that every trader post a certain amount of collateral, called an initial margin, on the trade date. Margin is a good-faith deposit required by the exchange to ensure that traders meet their obligations. It is not a down payment nor is it representative of the trader’s position in the actual commodity. Margin is insurance for the exchange in case a trader can’t meet their obligations. The initial margin will usually be large enough to cover a large one-day movement in the price of a commodity (typically 5 to 10 percent of the price).

After the transaction, there will be daily adjustments to the good-faith deposit based on the daily change in price of a commodity. Essentially, the daily adjustment will transfer money between traders. Every day, traders on the unprofitable trade will need to deposit more money into their margin accounts. That money will be paid into the accounts of the traders on the profitable side of the trade. Those traders can then remove the money and spend it. The exchange’s clearinghouse is responsible for handling all the debits or credits applied to each account.

Individual traders will commonly not transact directly with an exchange. Instead, they will authorize a broker to transact on their behalf. In this case, the exchange will charge the broker margin. Brokers will typically pass those costs along to their clients. As a result, even though clearing margins charged by an exchange are distinct from customer margins charged by brokers, they serve much the same purpose.

For example, let’s say a trader buys a futures contract for a 10,000 MMBtus of Natural Gas for December delivery priced at $6.35. The total value of the contract is $63,500 with an initial margin set by the exchange of $6,750. The trader will have to deposit that initial margin into a margin account. When the trader closes his position, he will get that deposit back. The next day, the price of oil falls by $0.15, giving the trader a loss of $1,500. That means the trader will have to deposit an additional $1,500 ($0.15 loss × 10,000 units) into his account. That $1,500 will be transferred into the margin account of some trader holding the other side of the position. The trader will not get back the daily margin when the account is closed. If instead of falling, the market raised $0.25, the trader would have received $2,500.

Every day, futures are assigned a price, called a settlement price or closing price, that determines whether the commodity moved up or down in price. This price is the same for both buyers and sellers. It determines whether each trader will pay or receive money through the process of daily margining. Every time the official settlement price of an asset changes, there will need to be a transfer of money. Essentially, the trades are closed and reopened every day.

Because of daily margining, a future contract is characterized by a series of small payments throughout the life of the contract. Every day, a little bit of money is transferred between the buyers and sellers of the contract. In contrast, OTC forwards typically don’t require money to change hands until the day of delivery. At that point, if the trade is financially settled, forwards will involve a single large transfer of money. If the forward trade is physically settled, it will involve an exchange of money for a physical product.

From the standpoint of an exchange, daily margining limits the exchange’s exposure to counterparty risk. Since the mark-to-market price should give a fair indication of where trading occurs, the exchange only needs to cover the risk of holding an asset for a single day. For example, if a trader fails to make a daily margin call, the exchange can take ownership of that futures contract and the initial margin supporting that contract. It will then liquidate the contract and keep the initial margin. As long as the initial margin covers the one-day loss the exchange is taking on the deal, the exchange will make a profit from the liquidation.

Since the risk taken on by the exchange is proportional to the daily price moves, initial margins will be higher on more volatile commodities. Generally, the initial margin will be slightly larger than the biggest one-day move expected in a commodity. It can also be based on the perceived creditworthiness of traders. Small traders, or those without strong credit, might be asked to submit a larger good-faith deposit than large traders or those with strong credit.

From a trading perspective, futures are typically used as industry benchmarks. As a result, many futures are liquidated prior to delivery. This allows them to have the benefits of trading without the hassle of physical delivery. Alternately, traders can negotiate their own delivery terms with other traders. If they do this, they will need to submit a contract called an exchange for principal (EFP) to the exchange. This exchange will then allow the traders to pair with one another for delivery.

Exchange for Physical

An EFP is a transaction where one trader will give another trader futures contracts in exchange for physical gas or crude oil. One of the traders (the one who wants to buy the commodity) will need a long futures position. The other trader (the one who wants to sell the commodity) will need a short futures position. The trader with the long position will give his long position to the trader with the short position, cancelling out both positions. The trader with the short position will then deliver the physical commodity to the trader with the long position in exchange for a mutually agreed upon payment.

Using an EFP allows traders to use futures to transact at a location (like New York) that is different than the futures settlement location. The process for settling futures with an EFP is:

1. The trader who wants to purchase the physical commodity will transfer futures (valued at the latest settlement price on the exchange) to the trader who wants to sell the physical commodity. This will cancel out the futures positions of both traders.

2. The trader who wants to purchase the physical commodity will receive the agreed upon physical commodity at an agreed upon location.

3. The trader who wants to purchase the physical commodity will pay the seller for the physical commodity. This price is typically quoted in two parts—the settlement price for the futures and a differential (a basis price) to the futures price.

From a trading perspective, EFPs are negotiated bilaterally but executed on an exchange. Some common points that have to be negotiated are the location of the delivery, the price adjustment that needs to be made, and whether the commodity being delivered will vary from the standard for the futures contract.

Forwards and Swaps

Forwards are trading contracts negotiated directly between two traders (i.e., a bilateral or OTC transaction). A swap is a general term for any agreement between two parties that obligates them to exchange something in the future. The term swap can be used to describe many different types of financial transactions. In the energy market, swap is most commonly used to describe a forward trade that settles in cash rather than by delivery of a physical commodity.

Like futures, forwards and commodity swaps allow traders to arrange a transaction at a specific time and place in the future for a contractually identified price. The major difference is that forwards and swaps are bilaterally negotiated rather than being cleared on an exchange. Negotiating a contract directly has both advantages and disadvantages. The biggest disadvantage is that both parties are at risk that their counterparty won’t deliver on its obligation.

In theory, forwards and swaps can be highly customized and give the traders the ability to negotiate customized contracts for unique or illiquid products. In practice, most forwards are highly standardized with terms and conditions similar to futures contracts. They are traded under standard contractual terms like the ones specified in the ISDA’s master agreement. A key term in this master agreement is a master netting clause. This clause specifies that all of the transactions between two parties will form a single contract. This prevents a bankruptcy court from enforcing some transactions and not others in event of a bankruptcy.

When forwards or commodity swaps are transacted, the transaction typically becomes an addendum to the master agreement and is documented as a short-form transaction (Figure 1.2.4). Occasionally, when two traders have never transacted with one another, all of the terms and conditions may be spelled out in the contract to create a long-form transaction. Short-form transactions are much more common than long-form transactions.

Figure 1.2.4 Trade confirm

One of the major drawbacks to forward trades is the counterparty credit risk that comes from direct agreement between a buyer and a seller. To minimize credit risk, traders who are involved in forward trading may require margin or other guarantees (like evidence of a guaranteed line of credit from a bank) from the other trader in order to make a transaction. Another way to limit credit risk with forwards is to use an exchange-based OTC clearing service. With this type of service, the trading partners arrange the trade themselves and then record the trade with the exchange. The exchange becomes the counterparty to each trader, essentially converting the forward into a future (Figure 1.2.5).

Figure 1.2.5 OTC clearing

Options

An option is another type of derivative contract. It gives the buyer of the contract the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell something at some future date at a fixed price. The right to buy is called a call option. The right to sell is called a put option. Options have an up-front cost, called a premium, which is paid when the buyer purchases the option. For the buyer, options have limited downside risk. Buyers will either lose their premium or they will make a profit.

In many ways, options are similar to futures, forwards, and swaps. However, unlike those instruments, the buyer of an option does not have to exercise his or her right to buy or sell. Options provide a way to ensure a worst-case price of an asset in exchange for an up-front premium. This premium can be very expensive. As a rule of thumb, buying options frequently loses money but occasionally makes a big profit. Selling options gives the opposite payout—a steady stream of small profits interrupted by occasional large losses.

TIME VALUE OF MONEY

Money in hand is almost always worth more than a promise of money in the future. For example, after winning the lottery, given the option of receiving payment of $10 million today or receiving the same amount of money 10 years in the future, most people would rather get paid today. Even if both payments were absolutely guaranteed, the ability to invest the money and spend the money today makes it a better alternative.

It would be a much tougher decision to choose between taking $10 million today and $25 million in 10 years. Then, it would be necessary to compare the size of the later payment against the expected investment return from investing the $10 million. The lottery winner’s expected return from his investments is called his individual rate of return (IRR). The consensus of every market participant’s IRRs is called an interest rate.

Interest rates are a measure of the time value of money and quantify the relationship between the present value of money (the value of cash received today) and the future value of money (the value of cash received sometime in the future). For example, a 10 percent annual interest rate implies that the market consensus is that $100 in cash today is equivalent to $110 a year from now. Alternately, at the same interest rate, the present value of $100 a year from now is approximately $91 today.

A separate complication to interest rates is the likelihood of getting paid. As a result, there are many interest rates available. The primary difference between interest rates is who is responsible for paying the money in the future. The more likely the debtor is to meet his or her obligations, the lower the interest rate. An example of a very low risk investment might be U.S. Treasury bonds or the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR). U.S. Treasury rates describe the interest rate that the U.S. government pays to borrow money. Another popular benchmark for interest rates is LIBOR, the rate at which major banks can borrow from one another (Figure 1.2.6).

Figure 1.2.6 Federal Reserve Board H15 report

Regardless of which interest rates are used, they all have several features in common. The first is that the rate varies depending on when the cash is expected. In general, the further off the expected payment, the less valuable it is in today’s dollars. This isn’t usually a linear process either. For example, the interest rate for receiving payment two years from now is usually not twice the interest rate received for a one-year delay (Figure 1.2.7).

Figure 1.2.7 Interest rate curve

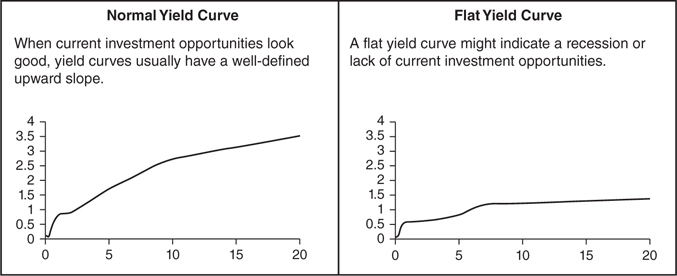

Interest rates, the shape of the interest rate curve, and the relative importance of credit quality all change over time. For example, a sharply sloping interest rate curve will typically occur when investors want their money immediately. If current investment opportunities are considered especially promising, having money today would allow investors to benefit from those opportunities. As a result, a very steep yield curve generally indicates a very positive outlook for the economy. In contrast, a flat yield curve generally indicates a negative outlook on the economy—investors are more willing to wait for their money if they don’t have any good investing opportunities (Figure 1.2.8).

Figure 1.2.8 Normal and flat yield curves

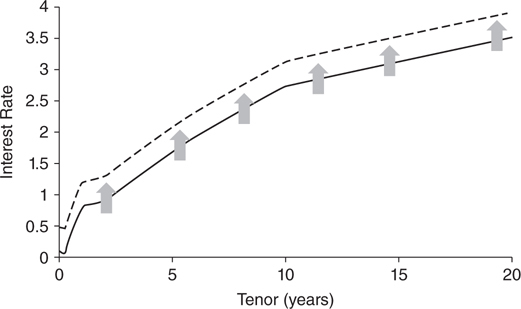

Likewise, it is possible for every interest rate to move up or down together. When all interest rates move together, it is called a parallel shift (Figure 1.2.9). Parallel shifts can occur because of concerns about credit quality or because a government is trying to inject money into or remove money from the economy. This generally indicates a large change in economic conditions.

Figure 1.2.9 Parallel shift

Because they change over time, interest rates affect the value of cash flows that will be received in the future. For example, at a 10 percent annual interest rate, the present value of $1,000 received in five years is $621. Through the bond markets, it is possible to sell that $1,000 in exchange for cash. However, if interest rates drop to 5 percent, the present value of the $1,000 payment rises to $784.1 For a trading company that routinely swaps its forward cash flows for money today, or vice versa, a change in interest rates represents an actual gain or loss in cash.

This is important to energy trading since most energy trades occur in the future. Interest rates have a big impact on the profitability of future cash flows. Going back to the previous section that discussed differences between futures and forwards, consider when these two instruments receive payments. A forward agreement has a single large cash flow that will occur at the end of the contract. In comparison, a futures trade will have small cash flows every day until maturity. The single large payment a long time in the future will be much more affected by interest rates than smaller payments occurring soon.

For small amounts of money, this effect might be small enough to ignore. For larger amounts of money, this can become a major source of risk. For example, a power company enters into a long-term contract to sell 500 megawatts of power an hour to an industrial facility between the hours of 7 a.m. and 11 p.m., five days a week, for 20 years. This is the output from just one fairly large power plant. If the price for a megawatt of power averages $75, that is a $3.1 billion exposure.

UNIQUE FEATURES OF THE ENERGY MARKET

Negative Prices

The established dogma in most trading markets is that prices can never be zero or negative. This isn’t the case in the energy market. While zero or negative prices aren’t especially common, they do occur. This can wreak havoc on many financial calculations. For example, in the stock market, a trader might remark that “the market is up 3 percent today.” However, for an asset with a negative price, dividing by the previous price will give an undefined or misleading result if prices are zero or negative.2

For example, if too much voltage is placed over a power line without any electricity being used, the power lines will melt. To incentivize power producers to decrease their power production, power grid operators sometimes make prices negative. Because of the costs associated with restarting power plants, many power plant operators would rather give power away for free than shut down their operations. Unfortunately, that preference can’t be allowed to destroy a transmission grid, and that means that power producers need extra motivation sometimes. The common way to incentivize producers to shut down is to charge them for every megawatt of power that they produce. In periods of negative prices, consumers can actually get paid for turning on all their lights.

Cyclical Markets

As mentioned earlier, in markets where commodities are rarely created, are storable, and never get destroyed, forward prices are based on the cost of buying the commodity in the spot market and holding on to it. Particularly if the commodity produces a benefit from being stored, like stocks that produce dividends, forward prices will always be higher than spot prices.

In contrast, energy prices are based on an intersection of supply and demand. Storing energy costs money, and the value of storing it decreases the more easily energy can be produced in the future. Combined with the fact that energy is destroyed when it is used, the fundamental relationship between spot and forward prices in the energy market is vastly different than financial markets where a “buy and hold” strategy is viable.

Energy prices tend to be dominated by short-term supply and demand issues. For example, a natural gas refiner might not be able to cost-effectively shut down his plant for the weekend and restart on Monday. If the industrial steel plant that uses the natural gas doesn’t operate on the weekend, there will be a surplus of gas on the weekends. Unless someone else can use it, or there is enough storage available, the price of natural gas on the weekend will be very low. The refiner will take whatever he can get paid rather than destroy the gas that is being produced. It doesn’t matter whether the world will run low on natural gas in 20 years. Today’s price is set by today’s supply and demand considerations.

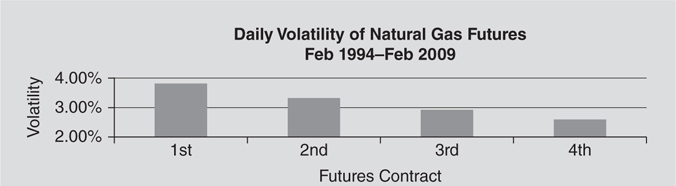

As a result, because prices are related to supply and demand, the future prices of many energy products tend to look cyclical (Figure 1.2.10).

Figure 1.2.10 Cyclical markets

Illiquidity

In liquid markets, it is easy for buyers and sellers to meet one another. It is also relatively easy to convert a financial instrument or commodity into cash. As a general rule, it is a mistake to assume that energy markets will be liquid. One reason for illiquidity is the prevalence in directly negotiated contracts. Even exchange-traded contracts can become illiquid more than a couple years into the future. For example, the NYMEX WTI Crude Oil contract is one of the most liquid contracts in the world. Most of the volume is observed in the first three delivery months and it trails off quickly after that (Figure 1.2.11).

Figure 1.2.11 NYMEX WTI open interest

Another reason is the importance of time and location to energy products. If an owner of an industrial facility in Alaska wants to lock in power prices, there are a limited number of parties that can actually deliver power to that location. There are no exchange-traded contracts that settle nearby, so it will be necessary to find someone willing to make a bilateral transaction. For example, an electrical marketer might trade with the industrial facility for a large enough expected profit. However, if that marketer wanted out of the position, there wouldn’t be anyone left to transact with. Other marketers are going to be afraid of making trades with the first marketer—if the trade is so good, why would the first trader want out of it? And, it will probably be impossible to unwind the trade with the industrial facility—the industrial facility is probably happy about being able to lock in their power prices.

Finally, another issue related to liquidity is that energy market participants tend to react as a group. For example, it is not unusual for all petroleum refiners or all power plant owners to come to approximately the same conclusions about the direction of the market at the same time. This creates a problem for trading since a liquid trading market requires both buyers and sellers, preferably in equal numbers. If everyone makes the same decision at the same time, there isn’t any trading.

Price Transparency

Compounding the problem of illiquid markets is the problem that accurate pricing information commonly does not exist. Unless trades are made on an exchange, energy trades are private contracts between two parties. Neither party is under an obligation to make those prices public. Quite often, energy traders consider pricing information to be competitively sensitive and actively discourage price dissemination.

A number of companies provide estimates of OTC pricing. These estimates are not actual prices, rather they are indicative prices that indicate where trades might be made. The data for these estimates come from surveys. Historically, traders would often be caught providing misleading data on prices in an attempt to influence trading. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the government agency that regulates energy trading, has since cracked down on the practice. However, if trading hasn’t occurred in a region recently, estimating the likely cost of executing a trade can still be extremely difficult. If the trade is initiated by a motivated buyer, the price may be a lot higher than expected. Similarly, if a seller is highly motivated to complete a transaction in a particular region, prices may be a lot lower than previously estimated.

Outright and Spread Trades

An outright position in a commodity is a bet that it will go up or down in price. For example, an outright position in electricity is a bet that electricity prices are going to rise in the future relative to current expectations of future prices.

Spread trades are an alternative way of making energy trades. Spread trades involve a simultaneous purchase and sale of related products as with buying natural gas and selling electrical power, or agreeing to buy natural gas in Louisiana and to sell in New York. In the first case, buying gas and selling power allows the trader to benefit if the price of electricity rises faster than the price of fuel used for power generation. In the second case, the trader will benefit if the regional price of natural gas in New York, a major consuming region, rises relative to the price of natural gas in a producing region. In both cases, the trader is relatively insulated from the actual direction of energy prices. This allows the trader to concentrate on the relationship between the two prices rather than the price of energy as a whole.

Compared to other markets, a very high proportion of energy trades are spread trades. The combined volatility of a simultaneous purchase and sale of related commodities is typically much lower than the volatility of an outright position. Since margin costs are proportional to the risk of holding a position, spread trades (trading two instruments simultaneously) can actually be cheaper than owning an outright position. Offsetting trades in one financial instrument with trades in a related financial instrument is called hedging. Because of the popularity of spread trading, the most common spreads have specific names.

Spark spreads are the difference between the price of electricity and the price of natural gas. They approximate the profit that natural-gas-fired power plants make by burning natural gas to produce electricity. Natural gas plants determine the price of electricity in many regions.

Dark spreads are the difference between the price of electricity and the price of coal without considering emissions costs. Coal-based power plants set the price of power in some regions, and dark spreads are commonly used in conjunction with the trading of carbon dioxide emissions. Dark spreads approximate the profit from operating a coal-fired power plant.

Crack spreads are the difference between the prices of refined petroleum products (usually gasoline and heating oil) and crude oil. Most commonly, crack spreads are a three-commodity spread. Crack spreads approximate the profitability of a crude oil refinery.

Frac spreads are the difference between the prices of propane and natural gas. Natural gas wells are the primary source of propane. This spread approximates the profit from removing propane from a stream of natural gas.

Basis

Because spread trades are so common in the energy market, terminology related to spread trading has a different meaning than in other financial markets. In any financial market, the term basis refers to a spread between two prices. However, in most financial markets, basis refers to the difference in price between the cash price of a commodity (the spot price) and some forward price.

But, since the energy market doesn’t have stable relationships between forward prices and spot prices, the term basis does not refer to a time effect. For example, in the energy market, the expected difference between the three-month forward price and the spot price will vary by season. Energy tends to be expensive in the summer and winter. It is inexpensive in the spring and fall. As a result, the rolling spot/forward relationship is just as cyclical as the prices.

Instead, in the energy market, the location of power is important. As a result, in the energy markets, particularly natural gas trading, the term basis refers to the difference between two locations. Since there is only a single delivery point for futures, the most common use for the term basis is to describe the difference in price of a specific location from the price at the futures delivery location.

1 A future payment is essentially a bond. Bonds are more valuable when interest rates are low than when interest rates are high. Bond prices and interest rates move in opposite directions. The financial market that trades interest rates is called the Bond Market or the Fixed Income market.

2 Negative prices break risk management systems. Finding the problems can take a long time and be extremely confusing if no one understands what happens with negative prices. Most people have a hard time grasping that a trading portfolio can be up 10 percent, lose a million dollars, and that the computer program calculating those numbers can be working as intended. In short, negative prices cause problems.