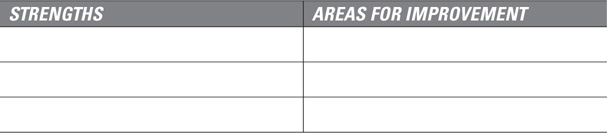

FIGURE 8.1 Organize Stage of a Selling Squad

Much research has been done over the last few decades about so-called “high-performing teams” in the workplace. One broad conclusion is that the word team is vastly overused in business. Putting together a high-performing team is a rare feat and takes time, even under the best of conditions.

The group of colleagues you have selected to join you for a client meeting may be a combination of the familiar and unfamiliar; internal colleagues and external partners; and skilled and unproven presenters. And while this meeting may be the most important entry on your calendar this month, your colleagues’ priorities may be quite different. Achieving a successful outcome requires you to turn this group into an effective selling squad, most likely in a short time frame and under high-stakes conditions. What could possibly go wrong?

The biggest mistake I see at this stage is lack of awareness around how complex the task is. Can you see the thought bubble floating over the head of an overly confident super seller? “It’s like me, but even bigger and better.”

Trying to stage such a transformation in a few weeks or days, when only a handful of intact work groups accomplish this over the long term, might be unrealistic. However, we can leverage lessons from the research on high-performing teams to raise awareness and build an understanding of what makes an effective unit.

Creating the Conditions for a Well-Organized Team

Here are some best practices on how to create the conditions that best allow the people you have recruited to work together effectively as a team:

1. Refine the group’s mission: You may recall from earlier chapters that your ability to convey the team’s mission, or mantra, is one of the marks of an effective leader. A mission is about more than winning the business or retaining a client. To inspire others to keep contributing, it’s important for you to define, and for the team to refine, what winning means for your organization and for the members individually.

2. Set performance goals: High-performing teams have clear, challenging, outcome-based goals and use these common goals to stay unified. In final presentations, the performance goal may seem clear: to win the business. How about all those other key meetings that lead up to the ultimate pitch? Here are two examples of what a group performance goal looks like:

![]() To move the customer from a neutral position to one where they express positive feedback on our value proposition, so that we can schedule another meeting to advance the discussion toward a new relationship.

To move the customer from a neutral position to one where they express positive feedback on our value proposition, so that we can schedule another meeting to advance the discussion toward a new relationship.

![]() To gain the customer’s agreement to not cut us out of the business, provided we are able to rebuild their faith in us and that we can get things right within 90 days.

To gain the customer’s agreement to not cut us out of the business, provided we are able to rebuild their faith in us and that we can get things right within 90 days.

Setting easy goals don’t inspire engagement. Crafting goals that are realistic but stretch people’s imagination has a motivational effect.

3. Identify challenges: There are no shortages of challenges leading up to a sales meeting. We could be lagging competitors on information, relationships, time, product, resources, capacity, and so on. By developing an honest and complete inventory of these challenges, you at least give yourself and your team the opportunity in your work together to try to close these gaps.

The word honest is intentionally used above. Have you ever been part of an organization or work group where people were strongly encouraged to always be positive? Being both positive and honest are not mutually exclusive. False positivity, however, as in “the Emperor without his clothes,” sets your team up for failure with a game plan that’s built on a faulty set of facts.

4. Clarify individual and collective work product: In advance of a sales meeting, there are numerous tasks that need to be completed. Some of these are best performed individually by team members; examples include developing an introduction and key messages during a capabilities discussion. Other tasks could be tackled by the group collectively. These might include the pitch book and meeting agenda. For whatever the group decides to approach as collective work product, ground rules must be established for both development and decision making.

These can include, for example, who in the group will lead the effort to develop presentation materials, what criteria will be used to decide what goes in and what stays out, and who has decision rights in case of disagreements.

5. Define accountabilities: As part of clarifying individual and collective work product, teams must also nail down accountabilities by task, owners, and time frames. This is about looking one another in the eye and making mutual commitments because the group understands that it will succeed or fail together.

There are countless tools, including Basecamp, that allow multiple people to manage, monitor, and communicate about projects.

6. Plan for conflict: Bringing together accomplished people can produce unpredictable results. At best, a group can produce greatness and perform like a symphony, transcending the performance of any one person. At its worst, group efforts can produce disasters. Imagine, for instance, a tankful of piranhas in a fight to the death, where each member competes against the others. If as an effective team leader you are successful in generating a fairly equal distribution of talk time among teammates, there will be no shortage of opinions.

With all voices heard, there will be conflict. The mistake most teams make is to seek consensus, avoiding conflict. High-performing teams, in contrast, are willing to fully understand differing opinions and give decision-rights to those who—because of their skills, experience, and interest—are in the best position to make a choice that helps the group accomplish its mission and goals, even if not everyone agrees with those decisions. Authors Jon Katzenbach and Douglas Smith call this “enlightened” rather than “unenlightened” disagreement. This means that even if you disagree with another team member’s position, you should at the very least understand their point of view. (Katzenbach & Smith, 2001, p. 114)

7. Sort through your communication plan: This should include agreeing on frequency, duration, format, and roles during team touchpoints. Technology such as e-mail groups and instant messenger apps can be great to help teams separated by geography and time zones connect before a group sales meeting.

8. Seek an objective feedback loop: To enable your team to make course corrections en route to your goal, be sure to seek and be open to feedback from people both within and outside your core group. Those closest to the opportunity and presentation may miss new information and changes in the buying process that are obvious to the extended group, less vocal members on your team, or your sales coach.

Enabling Feedback

Earlier, I talked about how to set up the expectation for a feedback exchange with a colleague. So, let’s briefly add to the topic here by discussing what feedback is and isn’t. Feedback can provoke stressful feelings in many people. “Can I give you some feedback?” Unless that question is being posed to you by a trusted, supportive colleague, you are most likely preparing to be attacked. Unfortunately, many people equate feedback with judgmental, unfair criticism because that’s the only “feedback” they have received.

What is “constructive” feedback? It’s information that when, accepted without filters, can help a person and team leverage strengths and address weaknesses. This assumes that the giver is trusted, and skilled at capturing and delivering information that is intended to help the receiver. It also assumes that the receiver is able to lower his or her defensive barriers to accept this information.

We will cover more fully in Chapter 18 a process for developmental coaching. But because feedback loops are such an important part of effective teamwork, it’s important to mention some tips here.

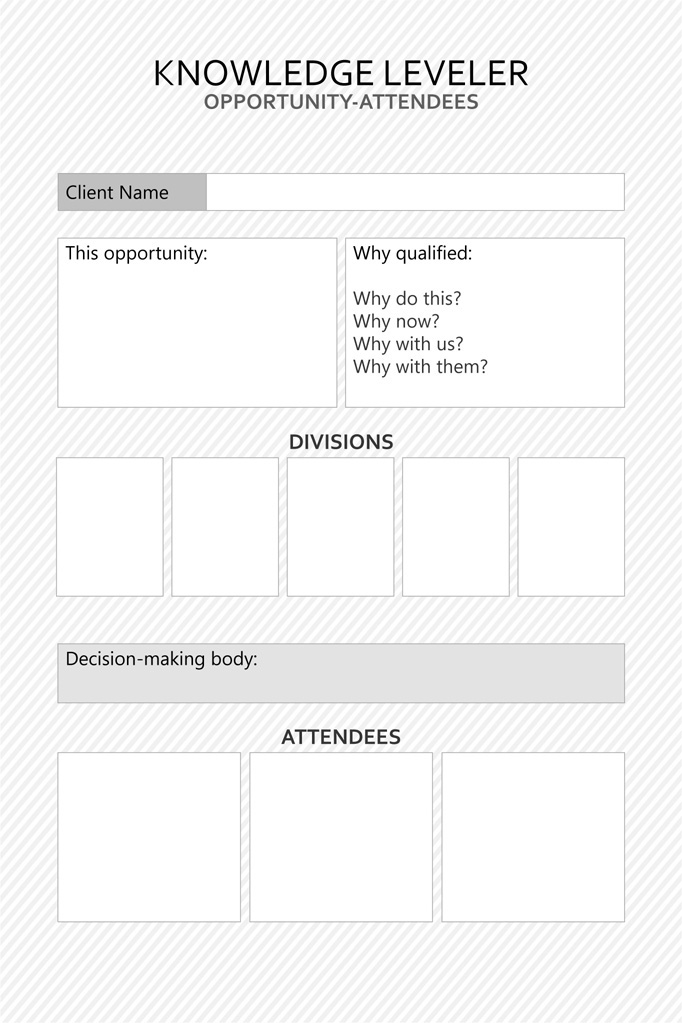

Constructive feedback is balanced, specific, and honest. (See Figure 8.2.)

FIGURE 8.2 Key Components in Sharing Feedback

Balanced means there is always one or more strengths, and one or more areas for improvement. No plan, idea, or comment is either pure perfection or utter rubbish. Figure 8.3 shows a balance sheet of feedback.

FIGURE 8.3 Balance Sheet of Feedback

Specific entails paying attention and taking notes so that you can offer advice about something that can be changed. An example of specific feedback would be: “What’s awesome is the way our game plan anticipated this new development in the client’s decision-making process.” Whereas, nonspecific feedback would simply be “That’s awesome.”

Honest refers to being direct. While some might shut out brutal honesty, excessive politeness that sugarcoats a helpful coaching tip with frosting and a cherry on top is equally ineffective at delivering the point. Find the happy medium: be candid with your comments, yet compassionate with the recipient’s feelings.

Receiving feedback can feel as uncomfortable as giving it. What seems to soften the blow is the notion of understanding and not judging what’s being shared. Consider asking questions to clarify and taking notes. You decide what, if anything, to incorporate.

Creating a feedback loop is essential for an effective team. This can include opening a channel through which information can flow from a coach or extended team member to the core team, or simply among team members. Feedback enables your team to adapt and improve its game plan, and allows individual team members to strengthen their contributions.

Once you have decided to pursue a qualified opportunity, and created your selling squad by identifying and recruiting the right players to play significant roles to help you win it, it’s time to organize your work together.

One of the investment bankers I coach shared with me a story about a past experience where she and two of her colleagues were asked to present to the CFO of a large, publicly traded company. Her colleagues were a managing director, the group’s leader, and a trader, a subject matter expert. Because this trio worked together before on a similar transaction, they set up a quick phone call to prepare. They reviewed the deal and defined roles, sorting out that the managing director would lead the meeting and explain the bank’s approach to structuring the transaction. The trader would address how the client would be protected from a large change in interest rates. And the banker role would to develop their pitch book and include content on the bank’s experience in structuring similar trades and illustrations on how the transaction would work. The managing director reviewed logistics and travel arrangements and promised to send background information on the company. They clicked off the call. Mission accomplished. Or was it?

They arrived on time, feeling confident. As the meeting got underway, the CFO seemed to like the proposed structure, with one exception: how the bank had proposed to deal with interest rate protection. The CFO felt the protection was not worth the cost and quickly dismissed this idea. The trader jumped in and argued his belief that what they proposed was the right way to do it, and reviewed the cost-benefit analysis. According to the banker, the meeting rapidly spiraled from a conversation to a verbal battle.

Their pitch failed to win the business. When the CFO returned the managing director’s call, the reason she gave was: “You didn’t seem to get what we were trying to accomplish.”

The group in this scenario had worked together in a similar transaction before, and rather than treating the new opportunity uniquely, they assumed it would be the same and chose to go into autopilot, simply substituting different names and numbers into a previous model that had worked for a different client in the past.

Author and Harvard professor Richard Hackman offers a number of gems that team leaders and contributors should keep in mind during the period before a pivotal meeting, including: “Mindless reliance on habitual routines results in suboptimal performance for many organizational work teams.” (Hackman, 2002, p. 163)

A group of colleagues who represent their organization at an important meeting tend to be smart, experienced, articulate people who know each other and their organization’s capabilities very well. And it’s that very experience, or familiarity, that triggers a “mindless routine.”

To transform a small group of professionals—sometimes from multiple disciplines, locations, and cultures—into a high-performing team in the short time frame between the client’s call and the meeting is no cakewalk. Groups that work together for far longer may never reach that goal. So after the CFO’s call, it’s important to start the process with an appreciation for the work involved to move your small group of smart and trusted compadres into an effective team. As we have discussed, this will not happen on its own.

According to Hackman, “the leader’s main task . . . is to get a team established on a good trajectory and then to make small adjustments along the way to help team members succeed. No leader can make a team perform well. But all leaders can create conditions that increase the likelihood that it will.” (Hackman, 2002, p. ix)

Common Pitfalls

Working together as a selling squad begins at your very first planning meeting, which I call an Organize meeting. Before we talk about how to conduct an effective Organize meeting, let’s look at some common mistakes you may recognize that pitch teams make at the start of their collective journey to an important meeting or pitch:

![]() Assume that an Organize meeting is unnecessary: Most commonly made by people who work together often, and especially those who work in the same location.

Assume that an Organize meeting is unnecessary: Most commonly made by people who work together often, and especially those who work in the same location.

![]() Assume that an Organize meeting can be done by phone: Audio- or videoconference is increasingly the only option in organizations that centralize shared resources, such as practice leaders and specialists, and decentralize others such as client-facing associates. For global opportunities, the direct and indirect costs of bringing people together physically would be impossible to justify. Those exceptions aside, groups that could easily get together still do not. And they miss opportunities to gel as a team.

Assume that an Organize meeting can be done by phone: Audio- or videoconference is increasingly the only option in organizations that centralize shared resources, such as practice leaders and specialists, and decentralize others such as client-facing associates. For global opportunities, the direct and indirect costs of bringing people together physically would be impossible to justify. Those exceptions aside, groups that could easily get together still do not. And they miss opportunities to gel as a team.

![]() Dump information: There is oftentimes an imbalance in customer knowledge among the selling team. One person in the group may have been cultivating the opportunity for some time and knows the most about the client situation. To correct the imbalance, there is often a knowledge transfer, which is a one-way flow of all information gained. Dumping information, without thought to how it is organized and relevant to the team, creates disengagement and is unlikely to serve as the handoff of knowledge that you intended.

Dump information: There is oftentimes an imbalance in customer knowledge among the selling team. One person in the group may have been cultivating the opportunity for some time and knows the most about the client situation. To correct the imbalance, there is often a knowledge transfer, which is a one-way flow of all information gained. Dumping information, without thought to how it is organized and relevant to the team, creates disengagement and is unlikely to serve as the handoff of knowledge that you intended.

![]() Accept core team absences: This includes both people who fail to show and those who are physically present yet visibly disengaged. If core group members are missing in body or spirit during your launch meeting, this may be a leading indicator of what their contributions are likely to be over the course of your work together. How will you get them up to speed on key information, the game plan, and their role? How will they begin meshing with other team members? If you’ve done sales calls with busy C-level executives (CEO, CFO, CIO, etc.), you’ve experienced how tough it can be for them to commit time to prepare. You’ve also seen, then, what can happen when they join the group farther downstream— taking over, overhauling the game plan, rapid-fire decisions, and more. Last-minute engagement by even the most collaborative senior executive or team member can throw your team off what would have been a winning path.

Accept core team absences: This includes both people who fail to show and those who are physically present yet visibly disengaged. If core group members are missing in body or spirit during your launch meeting, this may be a leading indicator of what their contributions are likely to be over the course of your work together. How will you get them up to speed on key information, the game plan, and their role? How will they begin meshing with other team members? If you’ve done sales calls with busy C-level executives (CEO, CFO, CIO, etc.), you’ve experienced how tough it can be for them to commit time to prepare. You’ve also seen, then, what can happen when they join the group farther downstream— taking over, overhauling the game plan, rapid-fire decisions, and more. Last-minute engagement by even the most collaborative senior executive or team member can throw your team off what would have been a winning path.

![]() Make this your only collective preparation session: Amazingly, many groups use this first meeting as their only meeting. The discussion is centered mostly on logistics and presentation materials for the client meeting. But, as you probably know or are about to discover, an effective sales pitch involves more than a group of bodies and presentation books.

Make this your only collective preparation session: Amazingly, many groups use this first meeting as their only meeting. The discussion is centered mostly on logistics and presentation materials for the client meeting. But, as you probably know or are about to discover, an effective sales pitch involves more than a group of bodies and presentation books.

So what does an effective selling squad Organize meeting look like? Let’s start with the basics.

Who Should Be There?

Ideally, your Organize meeting—or audio- or videoconference if needed—includes all core and extended group members. Especially for members who have responsibilities other than this customer situation, it is important to begin the process of grounding and aligning the people in what will hopefully become the team. Make your launch a mandatory meeting. The rule applies the same to a C-level executive as it does to a busy operations professional, each of whom committed to the pitch. No need to become a dictator or to lose your job over it, but the “mandatory” component of the launch meeting is as important in substance as it is in the message conveyed to your colleagues about the importance and complexity of the task ahead. Advance planning, using online calendar tools, and leveraging your relationships with the administrators who support your team members, will strengthen your ability to coordinate full attendance of your core team at the launch meeting.

When Should You Convene?

The easy answer is: the sooner the better. Even though there may be large gaps in what you know in the early stages, it allows you to begin creating a team vibe. How much time you have to work with will, of course, be driven by the client and situation. There is much planning to be done, and the sooner you can begin the more likely it is that you can avoid the heroics, stress, and mistakes that come with last-minute preparation.

What Should You Cover?

There are three broad areas that should be covered during all team touchpoints: knowledge leveling, planning, and practice. (See Figure 8.4.)

FIGURE 8.4 Organize Goals

“Knowledge leveling” is the process of making certain that all members of at least the core team are bringing each other current on customer information as the group gets closer and closer to the pitch. On some teams, nearly all customer information resides with one person. There are many instances where this is not the case. Your organization’s relationship with this customer may span across different parts of your organization and, within each, there are different leads and different client contacts. In this circumstance, knowledge leveling is done to accomplish the same goal, but the process is trickier and may involve both core and extended group members. There are commonly large gaps in what knowledge you have for the launch meeting weeks or days before go-time. These gaps help team members focus action over that time period to collectively fill those gaps.

The planning element acknowledges that there is a project management component to leading a selling squad effectively. Coordinating team touchpoints, materials, and other logistics, done well and in advance, avoid distracting eleventh-hour drama and embarrassing mistakes. Leveraging technology and extended team members can strengthen your team’s ability to plan, monitor, and execute its activities.

The final element to cover during team touchpoints is practice, or rehearsing. The connection between practice and an excellent performance is clear to artists yet, in my experience, not as widely embraced among salespeople. In fact, I sat down with a few artists in my network to get a sense of just how much rehearsal occurs before a final performance.

Evan Weinstein is a television producer on shows like The Amazing Race, which has won 10 Emmy awards for Outstanding Reality–Competition program. On this show, there are no actors, but you can imagine the logistics that are involved in staging and taping multiple teams following different paths at different times to try to reach the same destination. For Weinstein’s team, the process for testing key elements for one episode can begin 8 to 10 weeks prior to taping. (Dalis, Interview with Evan Weinstein, Aug. 7, 2015) While much of the show appears organic and improvised, there is in fact a great deal of planning and practice involved in creating that appearance. Similarly, a successful pitch should have that same natural, yet organized, feel.

Another artist I spoke with was Raymond Rodriguez, the associate artistic director for the Silicon Valley Ballet. Not only do each of the 32 dancers train and prepare individually, the full company of performers also meets for show-specific rehearsals. This process begins five weeks in advance of opening night and runs from 9:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. each weekday. That totals roughly 175 hours that Silicon Valley Ballet’s artists spend together before a production. (Dalis, Interview with Raymond Rodriguez, Aug. 11, 2015)

A sales or customer meeting is not a performance per se, and does not require the intricate coordination that a TV or ballet production requires among production staff and performers. Several weeks or 175 hours of practice time is unrealistic and probably not even needed. However, there is a lot of room between 175 and 0 hours. How much practice time would your team need to deliver the sales pitch you need to win the business—more than 1, fewer than 10? How will you decide?

For an Organize meeting specifically, let’s look at what bases should be covered on knowledge leveling, planning, and practice?

Knowledge Leveling

You’ve qualified and decided to pursue an opportunity that is going to require including others to win. If this is a strategic account, there may be a formal account team that includes representatives from across your organization’s lines of businesses; and you may have an established account planning process. At the other extreme, there are times that prospects and opportunities appear quickly and you find yourself with very little information and no prior history with the customer. While your access to stakeholders in either case may be limited, the availability of information in the public domain is enormous thanks to the Internet. So, what information needs to be shared with your colleagues who join your selling team?

I find that what gets shared by leaders with their teams, in practice, runs a wide range from a few crumbs to the whole bakery. The common thread among most knowledge sharing is that it takes the form of an information dump rather than a thoughtful parsing of need-to-knows. Common mistakes include sending a link to the buyer’s website or copying and pasting large sections from company materials. Leaving it to your colleagues to look it up themselves or sift through tons of text is not only inconsiderate; it’s likely to result in team members reading little if anything in advance, and arriving at your very important meeting with insufficient knowledge about the client. Internal colleagues and external partners who agree to join your selling efforts have priorities and responsibilities that may not align with yours, so it is important to aim for efficiency and relevance to properly and efficiently prepare them for your high-stakes meeting.

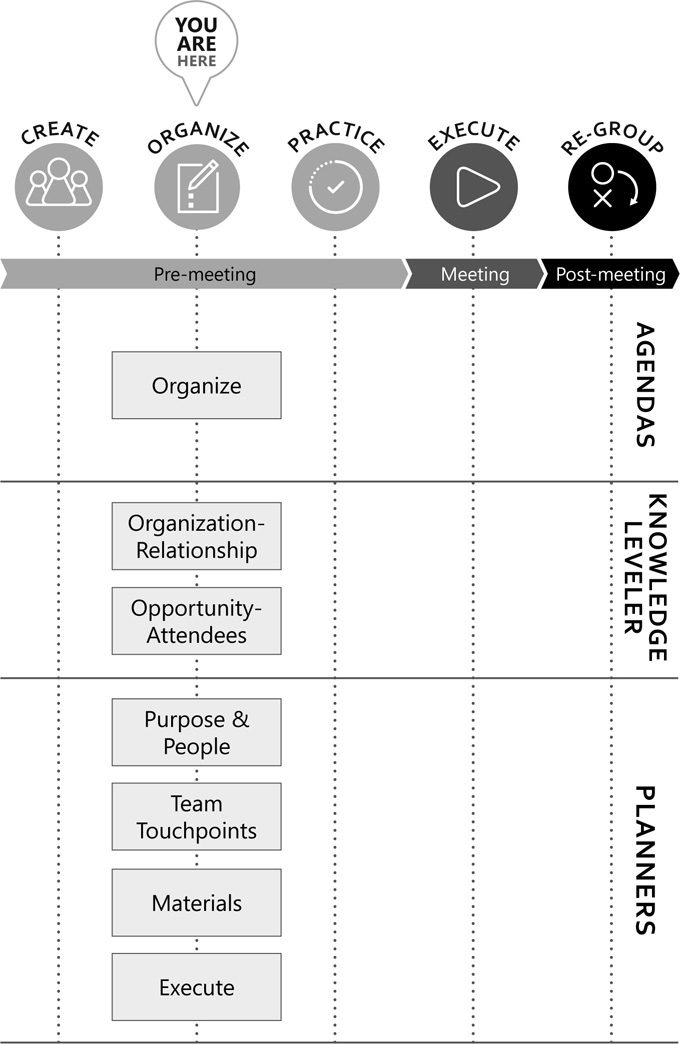

There is no shortage of information that could be shared. In my experience, the Knowledge Leveler form in Figure 8.5 contains what should be shared so that your team can better understand how they fit into the client’s buying or thinking process, and how their capability fits within your larger presentation.

FIGURE 8.5 Knowledge Leveler: Organization-Relationship

KNOWLEDGE LEVELER: ORGANIZATION-RELATIONSHIP

![]() Name and brief description: What works is a few sentences that give your team members a flavor for the person or organization—their industry/sector and role within it.

Name and brief description: What works is a few sentences that give your team members a flavor for the person or organization—their industry/sector and role within it.

![]() Mission: What is the client’s aspirational mission? At times, these statements are check-the-box statements filled with corporate jargon. For some people, families, and organizations, they can be a rallying cry; knowing both the mission and language used can help your team members tie a capability to that mission.

Mission: What is the client’s aspirational mission? At times, these statements are check-the-box statements filled with corporate jargon. For some people, families, and organizations, they can be a rallying cry; knowing both the mission and language used can help your team members tie a capability to that mission.

![]() Goals: If you have learned of specific metrics, such as earnings-per-share growth (for a publicly traded company) or percentage reduction in disease cases (for a nonprofit), against which the client is measuring progress, these too can be helpful as your team thinks through how to position key messages in a way that will resonate with stakeholders.

Goals: If you have learned of specific metrics, such as earnings-per-share growth (for a publicly traded company) or percentage reduction in disease cases (for a nonprofit), against which the client is measuring progress, these too can be helpful as your team thinks through how to position key messages in a way that will resonate with stakeholders.

![]() Key lines of business: It is not necessary to be exhaustive in listing every branch of the family or corporate tree, department, and trademark. Where does the organization or person generate most of its business? How does the customer organize itself? For example: “XYZ Healthcare has three main facilities and, within these, is known for five specialty areas (name them).”

Key lines of business: It is not necessary to be exhaustive in listing every branch of the family or corporate tree, department, and trademark. Where does the organization or person generate most of its business? How does the customer organize itself? For example: “XYZ Healthcare has three main facilities and, within these, is known for five specialty areas (name them).”

![]() The relationship: Provide brief snapshots of recent work that’s been done by your company for this organization. For each, include:

The relationship: Provide brief snapshots of recent work that’s been done by your company for this organization. For each, include:

• Scope of the work

• Size, in terms understood by your team

• Status: completed or in-process

• Outcomes: what was the result

• Connection to client’s key lines of business

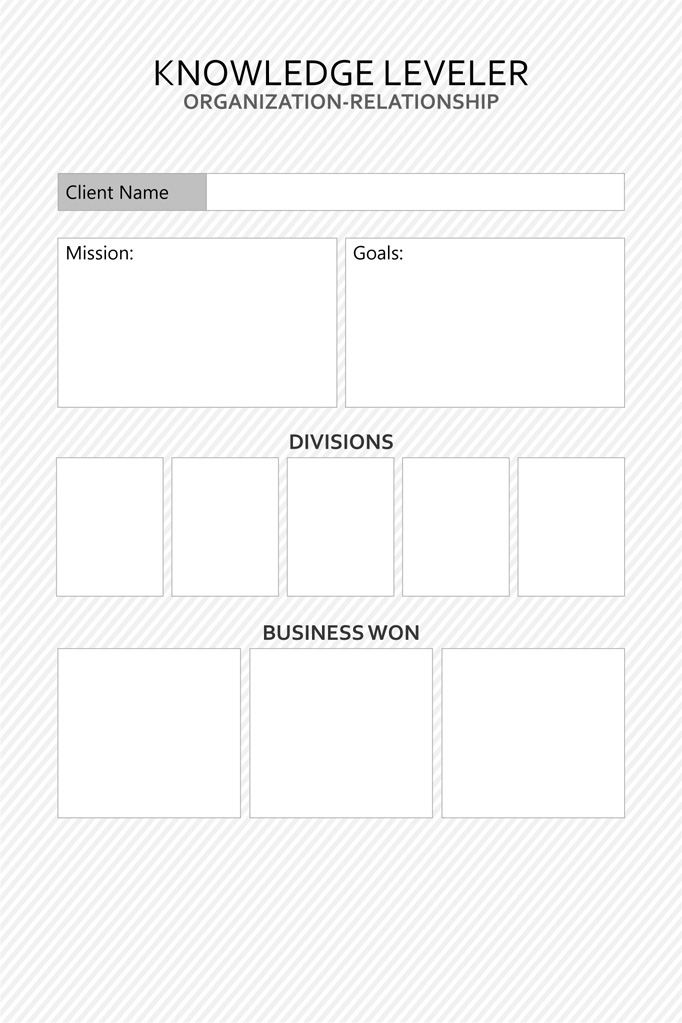

Figure 8.6 shows the knowledge leveler for the opportunity and attendees.

FIGURE 8.6 Knowledge Leveler: Opportunity-Attendees

THE OPPORTUNITY

![]() Description: Describe in a few sentences, using language your colleagues will understand, what opportunity is on the table.

Description: Describe in a few sentences, using language your colleagues will understand, what opportunity is on the table.

![]() Scope: What are the parameters, elements, components of the deal?

Scope: What are the parameters, elements, components of the deal?

![]() Size: Define size in a way that’s meaningful to your team members, such as assets, revenue, volume, and so on.

Size: Define size in a way that’s meaningful to your team members, such as assets, revenue, volume, and so on.

![]() Decision-making body: Who will make the selection decision? It may be a group of individuals, a formal selection or steering committee, a board of directors or trustees, or a committee under a board.

Decision-making body: Who will make the selection decision? It may be a group of individuals, a formal selection or steering committee, a board of directors or trustees, or a committee under a board.

![]() Issues: What have you learned from your contacts about what’s driving them to consider the cost and risk of a change? I worry as a coach when team leaders respond to this question with “They’re doing a search.” As a team leader, you want to be able to understand and convey to your team why the customer is considering a change. For example, the committee has lost confidence in the current provider to help their organization comply with impending regulatory changes. This will help your team members to formulate their value propositions.

Issues: What have you learned from your contacts about what’s driving them to consider the cost and risk of a change? I worry as a coach when team leaders respond to this question with “They’re doing a search.” As a team leader, you want to be able to understand and convey to your team why the customer is considering a change. For example, the committee has lost confidence in the current provider to help their organization comply with impending regulatory changes. This will help your team members to formulate their value propositions.

![]() Connection to key lines of business: Customer organizations can be large and complex. Helping your team locate where among the key business lines this opportunity fits simplifies the picture for them. For example:

Connection to key lines of business: Customer organizations can be large and complex. Helping your team locate where among the key business lines this opportunity fits simplifies the picture for them. For example:

Our flux capacitors will be used by Amalgamated Industries’ Construction Division to reshape time and space, so that they can come in under budget and on time in 100 percent of their projects.

![]() The reasons this opportunity is qualified: Recalling the four Why’s to qualify from Chapter 3, share the strength of your convictions behind:

The reasons this opportunity is qualified: Recalling the four Why’s to qualify from Chapter 3, share the strength of your convictions behind:

1. Why must the customer do this? Connect the opportunity to the organization’s mission and goals, as stated on the “Organization-Relationship” page.

2. Why must the customer do this now? Same consideration as above.

3. Why they should do this with you?

4. Why you want to do this with them?

![]() Their attendees: For each buyer stakeholder attending the meeting, convey to your selling team:

Their attendees: For each buyer stakeholder attending the meeting, convey to your selling team:

• Connection to key lines of business: Include title, plus key line of business with which they are aligned. Point out if their role crosses lines of business, such as for senior management or procurement. This will help your team visualize their counterparts’ roles in the client organization and how they connect to one another.

• Connection to past work: In snapshots cited above, point out which ones they were involved with and in what role.

• Role on decision-making body: What role do they play on this committee, board, or group? You may choose to keep this as simple as: leader, member, or advisor.

• Support strength: How strong is this person’s support for your organization relative to competing organizations—positive, neutral, negative, or unknown?

• Decision drivers: Whatever you have been able to discover about each stakeholder’s key drivers should be shared with your team so they can emphasize these points, where appropriate, in their comments

• Personal interests: For each attendee, what have you learned through your research that would allow your teammates to forge personal connections at timely moments—before, during, and after the meeting? For example, a recent trip to New Zealand, board member for local children’s hospital, or avid mountain biker.

• Participation: Will this person be at the meeting live, or virtually via audio or video link? Knowing this will allow your team to simulate this during your Practice session and to be well prepared for the actual meeting dynamics at go-time.

Your reaction after reviewing the Knowledge Leveler in Figures 8.5 and 8.6 may be something like, “How and when am I supposed to do be able to do all of that?!” Assuming you have qualified this opportunity, and carry that conviction in recruiting colleagues to the sales effort, your investment is already sizeable. Taking the time to level knowledge among selling squad members, in a format that will help them prepare and perform, may be the “lean at the tape” type of difference that will help you win a highly competitive sale.

You will find that using the Knowledge Leveler and other templates in this book will keep things simple and on point. Just as you would when communicating with a customer, breaking information down into pieces—or “chunks” as the behavioral psychologists call them—increase the likelihood that your team will read it, and your investment of time will pay off.

Planning

The project management component of selling squads is one that in my experience effective team leaders come to appreciate—not because they love it, but because early planning avoids last-minute distractions that take their team’s focus away from where it needs to be to execute a successful sales meeting.

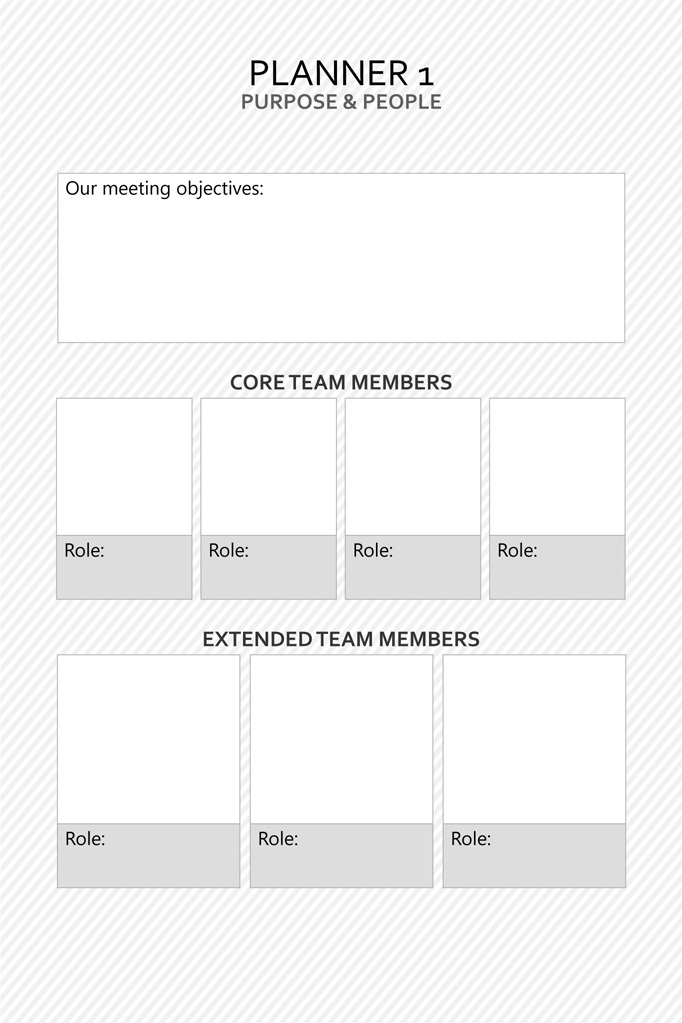

I have included planners to help you coordinate your team’s work together during the Organize stage. Let’s start with going deeper into Planner 1, which you started during the Create stage.

1. PLANNER 1—PURPOSE AND PEOPLE

![]() Goals: Objectives establish intent for a significant client touchpoint. (See Figure 8.7.) That old adage that applies here is, “If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there.” Both well-established and virtual teams make some common mistakes here, including:

Goals: Objectives establish intent for a significant client touchpoint. (See Figure 8.7.) That old adage that applies here is, “If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there.” Both well-established and virtual teams make some common mistakes here, including:

FIGURE 8.7 Planner 1: Purpose & People

• No objective

• An objective set only by the salesperson leading the effort

• Team has competing objectives

• A weak objective

It is not tough to spot the team that has fallen into one of the traps above. In fact, it can show up in the opening moments of a meeting, as soon the handshakes are over.

A strong objective focuses and aligns your selling squad. It has the same effect as a shopping list in a store: optimizing time and money, and putting you in the best position to accomplish what you came for. Solid objectives meet four criteria. They are:

1. Detailed: What commitments or feedback are you seeking?

2. Visible: What must the client(s) do or say to confirm the commitment or feedback you are seeking?

3. Timing: Within what period are you seeking that commitment or feedback?

4. Shared: The team is aligned on the above.

Discussing objectives early in your preparation calls or meetings gives you an opportunity to resolve any differences that exist among teammates. If you don’t budget time to hash this out in advance, this might just happen when the team goes live in front of the client. Clear and aligned objectives also enable the team to arrive at an important meeting better prepared.

For example: Let’s say that your team is preparing to meet with a prospective client for an early stage discussion. If your team’s (weak) objective was to get another meeting with this client, you might close the meeting by asking for another appointment, with the likely next step that you will check calendars and reconnect. Inefficient.

Alternatively, imagine that for the same meeting your team’s (better) objective is:

To gain the prospect’s commitment for a follow-up meeting over the next two weeks, to go deeper into the project’s scope and specs, with the key stakeholders in the line of business, IT, and procurement.

What could your team now do in advance?

1. Check your calendars for mutual availability, and come to the meeting prepared with days and times that work for the team members needed for the follow-up meeting.

2. Work with client contacts in advance to understand who from their organization would be important contributors to a deeper conversation. This would allow the team to be specific in gaining commitment for meeting details.

3. Think through the outline of what an agenda might look like, and what value the client would gain from that next conversation.

4. Decide who will ask for the meeting, and how he or she will describe and ask for it.

![]() Roles: Who from the core group will be playing what role in the pitch—leader, subject matter expert, technical expert, senior, junior, and so on. You may recall that this was something you thought about when building your selling squad. It’s important to put it to paper in the team’s shared document as a reminder that, regardless of what roles and titles we have in the company, we may play a different role in the sales meeting. Also be sure to note who will be participating live and who will be connecting virtually and through what medium. Knowing this will allow you to prepare for it.

Roles: Who from the core group will be playing what role in the pitch—leader, subject matter expert, technical expert, senior, junior, and so on. You may recall that this was something you thought about when building your selling squad. It’s important to put it to paper in the team’s shared document as a reminder that, regardless of what roles and titles we have in the company, we may play a different role in the sales meeting. Also be sure to note who will be participating live and who will be connecting virtually and through what medium. Knowing this will allow you to prepare for it.

You should also highlight who from the extended team will be supporting the core team and in what capacity—i.e., materials, logistics, coach, faux client, and so on.

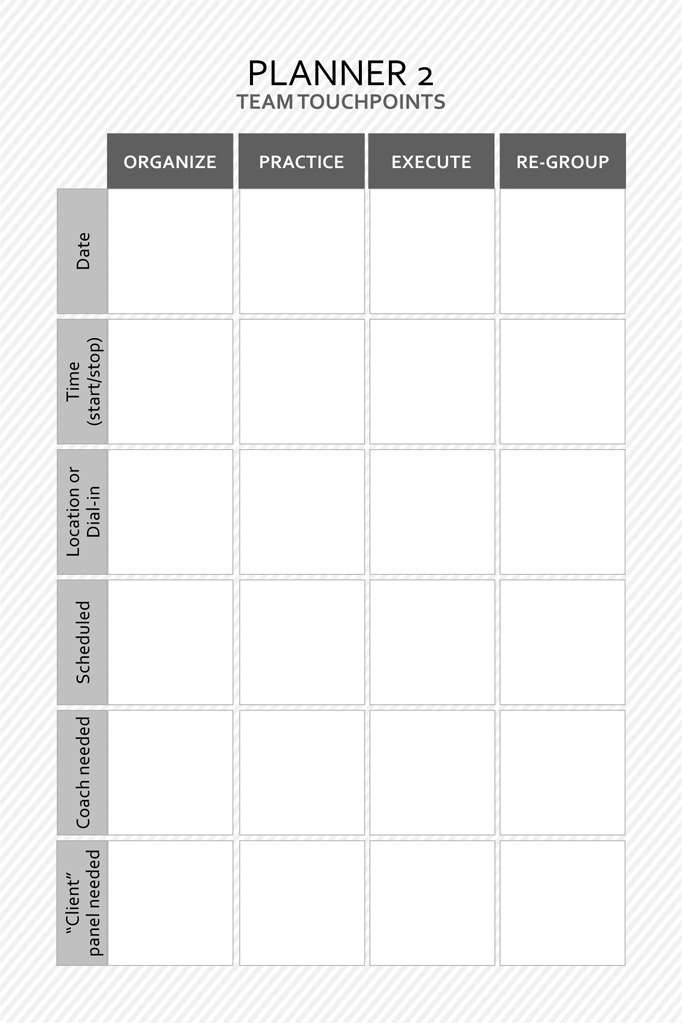

2. PLANNER 2—TEAM TOUCHPOINTS

Coordinating calendars for preparation among busy professionals can feel impossible at times. What helps is getting a jump start on this and involving team members. (See Figure 8.8.) This role can be a great one for a member of the extended group who is highly organized or someone who is being groomed as a future selling team leader. Increase your time efficiency by leveraging easy tools such as Microsoft’s Outlook calendar to scope out in advance of the launch meeting the time blocks that seem to work for everyone. At the launch meeting, try to nail down possible dates and times for a minimum of four team touchpoints:

FIGURE 8.8 Planner 2: Team Touchpoints

1. Additional Organize calls or meetings: A week or so before go-time, this touchpoint allows the team to do some knowledge leveling and to check in with one another on the state of their preparation before the in-person Practice meeting.

2. Practice meeting: This is a full-on, in-person practice (rehearsal) session. For teams that are geographically dispersed, this meeting can only feasibly happen the day prior to go-time. Teams that are geographically closer to one another or even in the same office are well served by scheduling more than one “Set” session and conducting these a few days prior to go-time; the extra breathing room allows for greater creativity and willingness to experiment with different sequencing, phrasing, and roles; and to address any open issues.

3. Execute meeting: This is your team’s last-minute huddle and client meeting logistics.

4. Re-group meeting: To debrief and plan, schedule this meeting for immediately or soon after the pitch. Advance planning ensures the full team will be available.

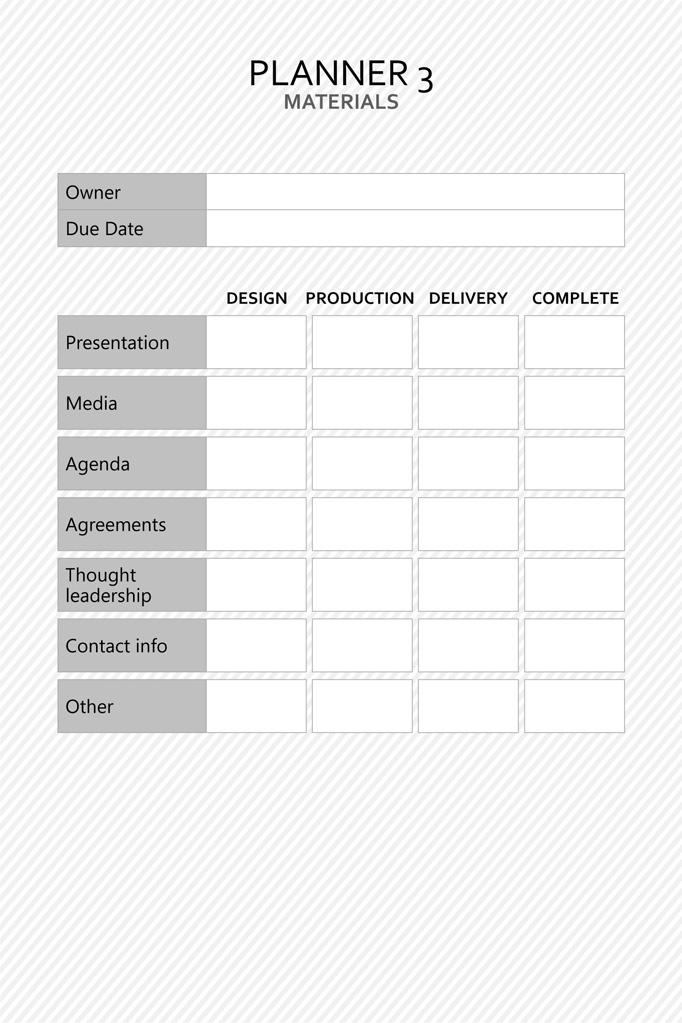

3. PLANNER 3—MATERIALS

As with scheduling meetings, collaborate early on a plan to develop, produce, and deliver materials to give your team the best chance of arriving at the meeting with the right materials and media, in good form. With customer knowledge now leveled, think through together what materials are relevant—presentation components, agenda, media (pitch books, projector, tablets), white papers, agreements, and so on—and plan accountabilities for each. (See Figure 8.9.)

FIGURE 8.9 Planner 3: Materials

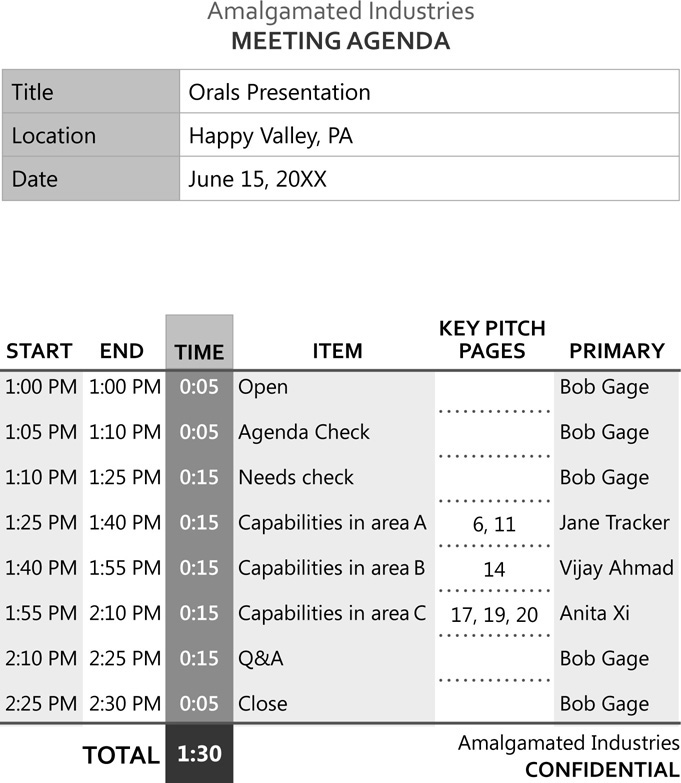

A few words on the importance of a customer meeting agenda. (See Figure 8.10.) You will want to begin blocking out with your team the elements of the customer meeting, from opening to closing; and for each section, how much time should be budgeted and who on the team will take the lead.

FIGURE 8.10 Example of Client Meeting Agenda

There are two common mistakes that can happen at this point: (1) there is no agenda or (2) the team uses the pitch book’s table of contents as the meeting agenda.

No agenda—written or verbal—suggests no preparation and no game plan, causing the client to become disengaged and to question the time committed to a meeting. This also gives the customer permission to create their own agenda, which might not work for you and your team.

A pitch book’s table of contents tends to make for a poor meeting agenda, and here’s why. The table covers the points in your presentation. Assuming these are all focused on you—your organization, your team, your capabilities—you can expect your team to do most of the talking and the client team to be largely disengaged.

Agendas that are in sync with buyer stakeholders are focused around their organization’s priority goals, challenges, initiatives, and more. If your industry and organization will allow you to, it is best to align your materials with the client’s goals. From my work with companies in the regulated financial services industry, I know that customizing presentation materials can be a nonstarter. Materials that are available to salespeople are the output of a review process that is designed to ensure regulatory compliance. If there is no flexibility in presentation materials, consider developing and bringing an agenda as a separate document. In less formal settings, sliding your agenda across the table over lunch won’t do much to keep folks comfortable. At least, come prepared to articulate your proposed agenda verbally.

Breaking down your agenda into two components—topics and time—allows you to check in with client stakeholders on both in your opening. Winning teams discuss and debate the agenda in advance to make sure it reflects the knowledge gained up to that point in the team’s client discussions. It also allows the team to assign ownership over who will review and check on the agenda and time, and how changes to these will be handled, in the meeting.

Make sure to budget time on your agenda for questions and answers and to close. The proper amount of time is driven by the total time allotted for the meeting. At a minimum, teams are well served by covering all other points 10 minutes prior to the stop time agreed to. This allows the team five minutes each to at least check for open questions and to close thoroughly.

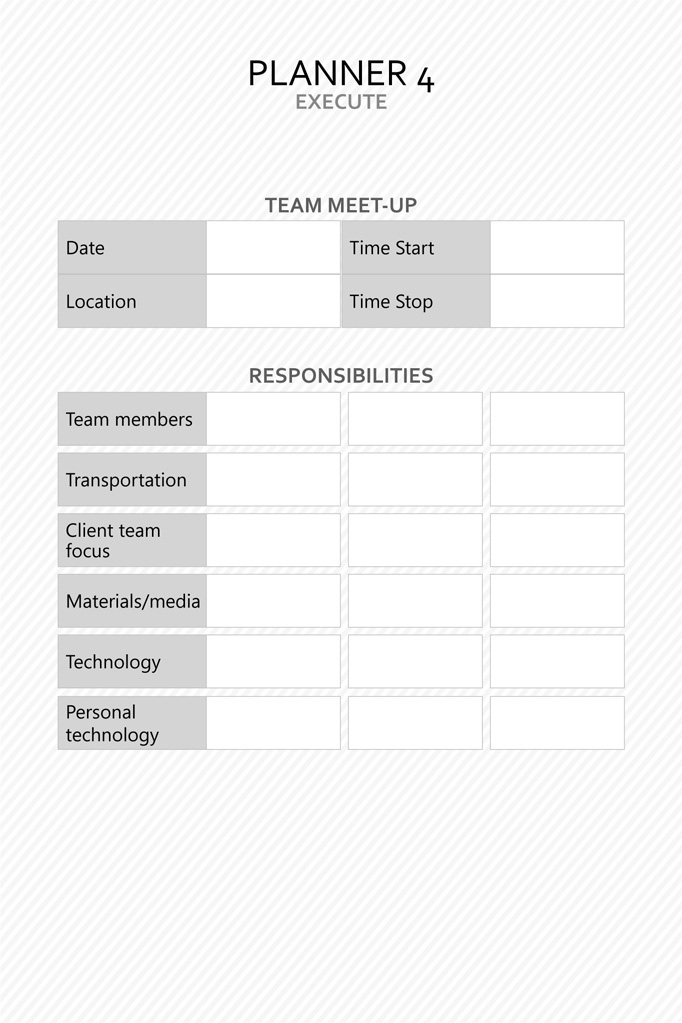

4. PLANNER 4—EXECUTE

Planner 4 allows the team to begin sorting out, as early as the launch meeting, logistics and responsibilities for presentation or meeting day. (See Figure 8.11.)

FIGURE 8.11 Planner 4: Execute

AGENDA: ORGANIZE MEETING

As your selling squad’s leader, you will likely be running the meetings or calls for each team touchpoint. So, it’s worthwhile to plan those agendas in advance, starting with your Organize meeting or calls.

We discussed the importance of an Organize meeting. Depending on the significance of the pitch or meeting for which you’re preparing, you might also wish to schedule one or more Organize calls. (See Figure 8.12.) This allows the team to benchmark the state of their preparation. Allocate time to knowledge leveling, planning updates, and even practice. I like to include a discussion on meeting objectives as part of the planning process, to ensure that the customer meeting agenda reflects what both the client and your team want to accomplish. Meeting objectives should meet the SMART criteria: specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, and time-bound. By engaging your team in thinking through what they would like to close on, you will enable them to focus more on outcomes and less on what information they can push out during their section of the meeting. The practice component of your Organize meeting is not a full run-through. Quick round robins on how people will manage introductions and key parts of their value proposition allow the team to get aligned, share feedback, and sharpen rough edges.

FIGURE 8.12 Agenda 1: Organize Meetings or Calls

Planning your selling squad’s Organize, Practice, and Re-group touchpoints as much in advance as possible ensures the best attendance and avoids rebooking travel arrangements, which can be costly.

Pre-practice

Using the Organize meeting agenda, the knowledge leveler, and the planning tools will keep everyone grounded and on point. If you have time during your launch meeting, you might consider budgeting 10 minutes or so for a pre-practice session. It ensures readiness, and sends an important signal that while practicing in front of colleagues can feel awkward at first, it is essential to getting better and gaining a successful outcome.

So what could you possibly practice without presentation materials and having just shared what knowledge exists about this opportunity? Here are some areas you might consider test-driving while the team is together during an Organize meeting or call:

![]() Introductions: Avoid an early opportunity for fumbling and instead get ready to start the positive momentum early. If you like to introduce your teammates in a meeting, allow them to hear and react to how you plan to do that. If you prefer to have teammates introduce themselves, ask them how they might introduce their role in this meeting or engagement if your team is successfully awarded the business, and set a benchmark such as 30 seconds or less. You will recall that effective teams create feedback loops, and here is another one. As each member runs through his or her introduction, feedback should be given by the team. (Remember, think: balanced, specific, and honest in giving feedback. And seek to understand and not judge when you receive it.) The team shares feedback so the person can refine his or her comments and timing. Then sort through what sequence you will use, and run through it two or three times. This is a short and easy way to get on a path to building early momentum in the client meeting.

Introductions: Avoid an early opportunity for fumbling and instead get ready to start the positive momentum early. If you like to introduce your teammates in a meeting, allow them to hear and react to how you plan to do that. If you prefer to have teammates introduce themselves, ask them how they might introduce their role in this meeting or engagement if your team is successfully awarded the business, and set a benchmark such as 30 seconds or less. You will recall that effective teams create feedback loops, and here is another one. As each member runs through his or her introduction, feedback should be given by the team. (Remember, think: balanced, specific, and honest in giving feedback. And seek to understand and not judge when you receive it.) The team shares feedback so the person can refine his or her comments and timing. Then sort through what sequence you will use, and run through it two or three times. This is a short and easy way to get on a path to building early momentum in the client meeting.

![]() Key messages: You’ve selected people to join you to contribute in certain ways. Given the territory they will need to cover in the actual meeting, it is helpful to begin road-testing some of those essential points and how they can be tied to the client’s mission, goals, and obstacles. And this work has another benefit: it’s an opportunity for collaboration, feedback, and support, so it builds teamwork.

Key messages: You’ve selected people to join you to contribute in certain ways. Given the territory they will need to cover in the actual meeting, it is helpful to begin road-testing some of those essential points and how they can be tied to the client’s mission, goals, and obstacles. And this work has another benefit: it’s an opportunity for collaboration, feedback, and support, so it builds teamwork.

![]() Success stories: Consider thinking through with core and extended team members what examples of similar work would resonate with the client. Discuss who should describe it, how, and at what point in the client meeting.

Success stories: Consider thinking through with core and extended team members what examples of similar work would resonate with the client. Discuss who should describe it, how, and at what point in the client meeting.

Also practice your team’s feedback loop by creating an atmosphere where balanced, specific, and honest feedback can be given and received safely and effectively. You might also consider engaging your sales coach at your first Organize meeting. Richard Hackman, in Leading Teams, offers the following:

A coaching intervention that helps a team have a good launch increases the chances that the track will be one that enhances members’ commitment to the team and motivation for its work. (Hackman, 2002, p. 179)

Staging a well-coordinated Organize meeting allows you as a leader to gain focus and set a collaborative tone. In geometry, making a small shift in the angle at the source of a line makes a big difference on where the end point lands. Similarly, when you make small adjustments at the start of your time together, as in your Organize meeting, it can be a highly efficient way to put your group on a path to becoming a team that accomplishes an important objective.