17 Presenting the Data as a Mobile Forensics Expert

Making a case after collecting a significant amount of data from a mobile device examination is only as good as the documentation. If the entire process, from seizure to data analysis, is not properly documented or explained in a way that’s appropriate for the audience, then a comprehensive and proper exam is often pointless.

Documentation is an examiner’s most important tool, especially when many different exhibits, methods, or custodians are involved. Without proper documentation, an examiner will be relying on memory or only the extracted and analyzed data. Recalling details from even a day prior is often difficult for most, let alone recalling every detail from the start of a process that may have taken weeks or even months to complete. An examiner must take detailed notes during the entire process. Notetaking at the onset and throughout the entire process is mandatory.

Before beginning the formal documentation process, an examiner should be aware of who will be reading the documentation. Often, if the evidence seems too complex or technical, the intended audience will not comprehend the message, and if they cannot comprehend the message, the examiner’s work will be pointless, no matter how significant the data. An examiner often neglects the technicality of what he or she has accomplished and regurgitates this technical journey in the documentation, without considering the audience. When the documentation presentation is too technical and is too difficult for the readers or listeners, the information provided may be dismissed. The examiner must find a way to express the details of the examination in a format and using terms that help the audience understand the gravity of the evidence.

An examiner should also be mindful of the data that should be a part of the completed report. Some examiners simply dump all the information into a document, place the information on a storage device, and hand it over to the requester/audience. But this often creates additional work for the requester/audience, because the examiner has confused details of the examination with what was actually requested. The documentation should be concise and to the point, but an examiner should always be able to elaborate, if requested, with additional information.

The journey to becoming a mobile forensic expert is long, and it is often misconstrued as gathering certifications, awards, and endorsements. But this is not the true path. Becoming a mobile forensic expert comes from a desire to find the truth within the data. In finding this truth, the examiner must follow processes and procedures, constantly research new technologies, meticulously document the process, and, most important, understand and supplement what the automated solutions are doing to recover mobile device data. The road to becoming an expert is paved with examiners who think mastering mobile forensic tools and achieving certifications are all it takes to get there. By this point, however, every examiner reading this book should recognize that this statement could not be further from the truth.

There is a difference between an expert in the field and an expert who has been qualified as an expert. The examiner should recognize the distinction between individuals who classify themselves as experts in the field by experience and accolades and those who give qualified expert testimony. One is not better than the other, but the examiner must understand the difference. One aspect of being a qualified expert witness requires that the following criteria be met and decided upon by the court—and no one else. In the Federal Rules of Evidence, “Rule 702. Testimony by Expert Witnesses” (www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_702), specifically states that expert opinions may be admissible if

(a) the expert’s scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will help the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue;

(b) the testimony is based on sufficient facts or data;

(c) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods; and

(d) the expert has reliably applied the principles and methods to the facts of the case.

Even if Rule 702 is not followed, most U.S. states and many nations adhere to this philosophy, with similar requirements. Courts require that the witness be competent on the subject and know the underlying methods and procedures used in the examination and relied upon as a basis on the opinion.

Presenting the Data

When presenting the data, an examiner must consider several factors that are generally based on the audience or individual requesting the work. The format should be established at the onset of the examination so that the examiner can tailor the examination to meet the requirements of the requestor. Determining the presentation format up front saves the examiner time and resources. Failing to comprehend how the data should be formatted from the beginning can result in the examiner following the wrong path, which can result in an exorbitant amount of time and sometimes money to remedy.

An examiner should also understand the target of the examination at the start. The investigation of the mobile device data should provide insight into the investigation, with not only the “tip of the iceberg data” but also a massive amount of relevant data located within the device file system. An examiner should be able to target specific apps for investigation according to the requirements of the investigation, but he or she should also not dismiss any other relevant data uncovered during the investigation.

The relevance of the collected data is determined by the presentation of what data was collected and how. For example, merely stating that a message was sent from Google Voice to another device that received it via an SMS is often not enough—the data should correlate the sent message in the Google Voice app with the data from the receiving device’s SMS message container, relating the date/time, time zone, content, and user ID to the relevant factors of the investigation. Furthermore, the examiner must detail and document SMS messages, which can be sent from third-party apps to other mobile devices. Using apps for messaging instead of the carrier SMS conduit occurs frequently. Consequently, the sender using Google Voice can hamper a mobile solution’s ability to recover a message from the standard SMS messaging because it was sent from a third-party app. Moreover, since third-party data messaging content is not kept, stored, or cached at the telco server, it is important that the examiner document when content was recovered on the device. Including this type of information within the presentation documentation is critical, especially for data that is significant to the outcome of the case. Outlining the importance of the data as it pertains to the overall case, using common language and including lots of information, is critical.

Unfortunately, however, use of the many available mobile forensic solutions can lead to confusion when it comes to documentation—not only because of the number of varying reporting formats but also because of several different aspects of the documentation. An examiner may complete the processing of the mobile device, select to output the data into a report format, and move on to the next piece of mobile forensic software. The data is processed in the secondary software, or the device is collected again and another report is generated. This secondary report may contain additional data that the first solution did not contain, but it may also duplicate data included in the first software’s report. The problem is not in the employment of multiple tools within an examination, but the improper presentation of this material.

No matter whether one or multiple tools are used in a mobile forensic investigation, one report should outline the complete seizure, collection, and analysis, and any reports created by the mobile forensic tools should be used to supplement the main document, because they often do not contain enough detail or commentary.

I can recall several instances when a Cellebrite report comprising thousands of pages was entered as evidence. Legal teams pored over the pages, searching for germane data, with absolutely no idea how the information was obtained, where it was obtained from, or what the data actually meant to the investigation. This issue is not limited to Cellebrite, because practically all mobile forensic solutions ordinarily output generated data compiled by the automated methods that place no value on the process by which it was collected or the requirements of the overall case—that is left up to the examiner. Unfortunately, many examiners do not add information to the solution’s automatically created report. But without including important details in the presentation, the audience may find it difficult or impossible to comprehend the meaning behind the data hidden within the many pages. An expert is not defined by the number of pages generated by an automated tool, but by the explanation of the content that is presented with the supporting tool’s output.

The Importance of Taking Notes

The entire process, from seizure to analysis, should be documented in chronological order in the examiner’s notes. The date and time of each function should accompany any details of the event, along with all observations. Using these detailed notes, an examiner can paint a picture of the event precisely how it occurred. An examiner may attempt to recall the entire event during the final documentation phase, but in doing this, he or she may leave out many forgotten but valuable details.

Guessing and filling in the blanks of an examination is never the right choice. By documenting every detail at every step, the examiner will be sure to include even the minutest detail in the final report. Suppose, for example, that an examiner “always” places a device in airplane mode as soon as a device is seized, and he never documents this process because it’s always the same. He always writes the report and adds this detail at the end of the examination. However, on this particular case, he’s not entirely sure he remembered to place the device in airplane mode because he was interrupted by an important phone call just as he collected the device. Still, because he believes he always follows the same procedures, he writes the report assuming that he followed his usual routine. Another examiner is called to validate the findings of the first examiner and happens to look into the settings file. She determines that the mobile device was not put in airplane mode at the time of seizure. The entire first examination is discredited and may be deemed unusable.

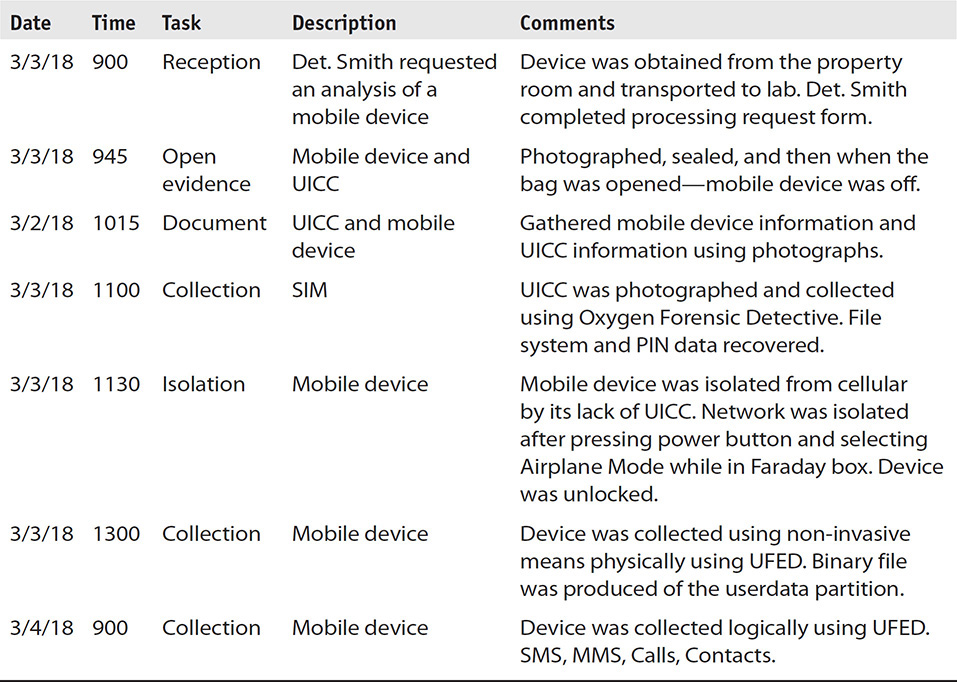

Instead of guessing, the examiner can create a Chronology log. This log is a detailed grid similar to Table 17-1, which can be filled out to include the various tasks with clear details for later recall. This is similar to a log of the events, and it will help the examiner immensely when recalling each task and resolution when later writing a report.

TABLE 17-1 Sample Examiner’s Notes Table Used to Document Every Detail of the Investigation, from Reception to Reporting

When completing any notes of the event, the examiner must understand that any documentation produced as part of the investigation is discoverable. In other words, the examiner’s notes can be requested as part of the proceedings if he or she was not acting as a consulting expert based upon Federal Rule of Evidence 502 and Federal Rule of Civil Procedures 26(b)(A). If the examiner is acting as a consulting expert and will not be testifying but is advising counsel, his or her notes are a work product and protected under attorney-client privilege, understanding that these drafts are legal advice and the attorney rendered legal advice based on the draft. With that being said, the information contained within the examiner’s notes should be free from generalizations and opinions and should simply state the facts. The only facts that should be included in the examiner’s notes are the procedures taken and the outcomes of completing the procedures. Listing opinions, comments, or even doodles in the margin could result in considerable hurdles during the court proceedings, particularly if the court requests these documents. The notes should be used for an examiner’s recollection of the entire process, and they serve as a guide as the examiner creates the final presentation of evidence.

The Audience

The audience is any person or group of people who will be exposed to the investigational report created by the examiner. The audience could be the examiner’s supervisor, human resources, a company CEO, an attorney, a jury, a judge, or any other entity coming into contact with this compiled information. Knowing the audience of the produced documentation can help guide the examiner during the final documentation phase. The presentation of the materials should be compiled in a form that caters to each group or individual person mentioned, but it should also contain information as it relates to the specific audience that requested the report. For example, a report created for the CEO of a company may contain sensitive information that is not appropriate for an employee of the company. This does not mean the examiner should permanently omit data, but he or she should be selective in providing the information needed and requested for particular audience members. When the examiner creates reports using automated tools, this can be difficult unless some sort of filtering is available. This is an important reason why an automated report should supplement the main documentation: the primary document will contain information specific to the request, outlining the details of the collection and analysis of the scoped data, and the supplemental solution report can be used in a redacted form. Of course, if the requesting party wants to see the information originally omitted, that would not be a problem, because a full collection would have already been completed and a more verbose report created.

![]()

A full collection should always be completed unless a full collection exceeds the scope of the request or warrant. In those limited cases, only a portion of the information will be available, as outlined by the requestor or warrant. If additional information is requested outside of scope, an examiner should follow proper procedures in obtaining the right to gather this additional information from the device.

Knowing the audience and creating a pointed report that details the information specific to the audience will resonate more than producing a generic solution report containing all data. Having regard for the viewer and targeting the report based upon his or her request will often mean little follow-up work by the examiner. By giving the audience member the data that was specifically requested, in a form detailing the examination, analysis, and findings, the examiner will satisfy the requirements set forth by the audience. Delivering a 1000-page report that requires the reader to decipher technical details can result in many questions and more work for an examiner after the fact. If an examiner bases the presentation on the audience, outlining and detailing the data to fit the request, he or she is sure to meet the needs of the request.

Format of the Examiner’s Presentation

In addition to knowing who the report’s audience is, an examiner should know the type of format that is required for the report. The format can be dictated by the working standard operating procedure (SOP) by the company or agency sponsoring the collection and analysis. Most automated tools’ reporting systems output reports as Microsoft Word documents, PDFs, HTML documents, CSV documents, and sometimes XML. Because the output produced by these tools will be used to supplement the main document, the format of this report often is not as important to the audience as the main document’s format. However, if the audience has requested the solutions output in a format such as CSV or XML for specific reasons, such as to import it into intelligence software such as i2 Analyst’s Notebook, the type of supplemental documents provided does significantly matter. This formatting information should be discussed and settled prior to beginning the collection and analysis of the mobile device evidence.

The main document may be created in a word processor such as Microsoft Word or Apple’s Pages and then saved and printed as a PDF. Some agencies and companies have internal word processing applications specific to their business; these are completely acceptable to use since most will output to a PDF. A PDF is important for final documentation, because the content within the PDF remains read-only. Of course, if the company or agency format is different based upon an SOP, the SOP should be followed so long as the final output cannot be modified. Some agencies and companies use HTML for their reporting to organize and display their findings. This method can be used as well, but a main report should always be included as a PDF, and the HTML format should be used for navigation purposes only.

![]()

It used to be common practice to use HTML with an auto-run function, but because modern operating systems allow this function to be disabled, using this methodology is not advised.

Whatever the format of the completed report and supplemental data, the examiner should organize the information using the following guidelines:

• All information should be placed on storage media (such as CD, DVD, flash drive).

• The information should be categorized within a README file in the root of the storage media that outlines the contents. An example is shown here:

![]()

• If the examiner will be using HTML pages, the main index.html and associated files should be placed into a separate folder named HTML Report and listed in the README.txt file with instructions on its operation.

• If the examiner has placed media files within the evidence folder, the audience might need special software to view the material (such as .mov, .mp4, .qcp files). The viewing software should be included in a folder called MISC Software and its use and need described in the README.txt file.

When the information is organized by the examiner, the audience is less likely to request an explanation or require assistance from the examiner when viewing the results. Making information clear and concise will save the examiner from unnecessary requests, saving time for both the audience and the examiner. If documents are produced as a hard copy, all pages should be initialed by the examiner to ensure the integrity of the documented data.

Why Being Technical Is Not Always Best

When documenting the process, procedures, and analysis, the examiner should remember to write in a way that the audience will understand. Often, a forensic examiner will create a document that contains information that only another examiner will understand, but this defeats the purpose of the report. An examiner should think in terms of customer satisfaction when creating the main document and any supplementary documents; all should be written and compiled so that a person with absolutely no forensic background or technical experience can visualize and comprehend the contents.

![]()

If the client requests that the examiner create a PowerPoint presentation to explain his or her report, this is a clue that the information contained in the report does not paint an understandable picture of the procedure and data.

Examiners must understand that the report’s audience may have an entirely different perspective regarding the data. Using jargon and acronyms known only to mobile forensic examiners can confuse and frustrate a reader who is not versed in these terms. A report can be quickly dismissed if it is simply a well-written document that only the examiner understands. The most frequently requested change clients make when receiving an examiner’s final report is to explain the technical jargon used in the document. Some examiners go the opposite route, “dumbing down” the content. This has the same effect on readers, who realize the author is “talking down” to them. The examiner is challenged to find middle ground to discuss technical aspects, procedures, analyses, and conclusions in simple terms, but not so simple as to demean the readers.

An examiner may find that using analogies can help in documenting the technical aspects of the device analysis. By using everyday, real-life examples, an examiner can describe a technical procedure within the document or during testimony by comparing the information to something more familiar. For example, if the examiner includes information about unallocated space, he or she might compare it to a shelf in the public library. The user goes to the catalog system, looks up a book by the author or title, and is directed to a shelf where the book is located. However, not all books are referenced in the catalog system—perhaps they have been removed to discard—yet they still exist on a shelf somewhere in the library. The books may still be read, and they still physically exist, but they cannot be found using the catalog. Unallocated space is like the shelf where the discarded books are stored, and the information stored here is similar to the discarded books. This storage space contains deleted files, file remnants, and empty space. Because the files within the unallocated space are not referenced within a file table (catalog), an examiner must search to find each file within this space.

“Tech speak” is best left to conversations with other forensic examiners, but sometimes technical terms and concepts must be included in a forensics report. In this case, the document should contain a list of terms used in the document and simple definitions. The definitions should explain each concept in an appropriate way so that the audience will understand. An examiner can then reuse a definition document for each examination as needed.

By creating a nontechnical document that caters to the intended audience, describes the processes and procedures, and supports the conclusion based upon the evidence, additional explanations to the content are seldom needed. An examiner should strive to produce a concise, detailed document that can stand on its own without additional explanation or commentary.

What Data to Include in the Report

The content of an investigatory report should be consistent and structured so that the examiner can use a similar format for each mobile device investigation report. When an examiner creates a report using boilerplate language and format, he or she can use the same configuration for each examination, with adjustments as appropriate. Creating a well-functioning document starts with a well-formed outline. The examiner can use the outline during the examination and analysis phase to help with documenting the appropriate details and focus on the particular requirements of the outline, which often results in a more detailed report.

![]()

The information contained within this section is only a recommendation. An examiner can add, remove, or modify these suggestions to fit his or her own needs. Some critical items should always be included in investigatory reports, and these are noted within the context.

What Right Do You Have?

The initial information in the report should indicate not only how the examiner received the mobile device and conducted subsequent analysis but also what right the examiner has to collect and analyze its contents. If a search warrant had been obtained to search the device contents, the examiner must indicate this. If an examination does not require a search warrant (for example, consent is given to search, a private investigator is searching, the device is enterprise owned, or the examination is part of a contract), these details must be included in the report to describe why this search and analysis could be legally conducted. Failing to describe the examiner’s right to conduct an investigation into mobile device data commonly results in additional questions and concerns from the intended audience.

Documentation that describes the legality of the examination should be included in the Supplemental Documents folder. The text within the rights section of the final presentation will distinctly outline the contents of the supplemental documents and will refer to the location in case the audience needs more detail. Also, the chain of custody form for all exhibits should be included in this folder and should also be documented within the main document. By including this information in the overall presentation, the examiner lays the foundation for the validity of the entire mobile device collection and data analysis. This section should be a mandatory part of all documentation.

The Five W’s

Who, what, when, where, and why are known as the “Five W’s” and are important in all types of writing efforts. Most notably, law enforcement practitioners use these to develop questions to answer when creating reports and also while handling investigations. The answers to these questions should appear at the beginning of the mobile device examination report to set the stage for the processing section of the piece.

The content in the initial portion of the document should clearly introduce the Five W’s, setting up the rest of the content and the examination process. By outlining this information first, the examiner helps the audience better understand the rest of the document and supporting materials. When the examiner quickly dives into “This is what I found,” readers may be overcome with information overload. Setting the stage for the readers and slowly outlining the necessary materials will give them context for the upcoming content. This section should be a mandatory part of the documentation.

The who question is not necessarily “Who dunnit” for an examiner, but a statement of who requested the mobile device processing—often this is the primary investigator, but it may be the person performing the examination. When a request comes from the primary investigator, the examiner should document not only the name of the individual but also the information surrounding the request. If an investigator has requested that the examiner process “a Samsung SGH-i535 mobile device for documents sent from Bob Kelly to Major Tom sometime between April 1st and April 5th, containing classified materials,” this information should be included as part of the what, when, and where questions. In addition, the who may be other persons involved in the case: “Mary Todd, the plaintiff, allowed her iPhone 8 to be examined as part of an investigation surrounding an internal workplace complaint. Ms. Todd stated she had received threatening messages on June 1st, 2017, from Mr. Roger Dokken, her supervisor.” The what and when along with where can also be satisfied within this statement. Of course, an examiner should elaborate on each point, making sure every detail is outlined within the processing document completed by the subject who requested the mobile device examination.

The why question should explain to the audience the reasons the examiner has been tasked with the collection and examination of the mobile device. Furthermore, it should describe what this particular request for processing has to do with the overall case.

With mobile devices today, just “dumping” a phone, hoping to find something, is like trying to find a needle in a haystack. Massive amounts of data are stored within mobile devices as well as within the Cloud, and an examiner must have a clearly defined objective prior to starting the examination. This objective is the why portion of the document.

Tools Used

The next section of the report should outline the tools used throughout the process, including software used to isolate, collect, analyze, view, and report data. The information can be in table form (see Table 17-2) and should include the company that produced the software, a link to the software, the version number used in the analysis, and a comment section. By listing this information within the main documentation, an examiner can duplicate the entire process if necessary.

TABLE 17-2 Example Table Listing Software Used During the Examination Process

Usually, two experts are consulted in a trial—one will validate the findings of the other. By listing the specific details for each hardware and software title, along with version numbers, a second examiner can set up the same environment used in the original analysis. Another reason for including the software titles and version numbers is to assist the initial examiner. By being able to recall the software used in the examination and the version number, the examiner can resolve problems if current software versions do not provide the same results at a later date. Using the software version, the second examiner can install the exact version that was used for the initial examination to ensure a proper verification and validation platform. This may seem like overkill, but with the constant updates to mobile forensic software, there are bound to be changes that could affect an evidence image. Examiners should maintain all the versions of the software, if possible.

![]()

Maintaining all versions of the software is not mandatory, because storing many versions can be difficult and expensive. However, most software vendors provide a repository where examiners can download past versions, so maintaining the storage site is unnecessary. An examiner should become familiar with these locations for all software that will be part of his or her mobile forensic toolbox and know how to obtain old versions when needed.

Isolation Methods

As part of the main report, the examiner should include how the device was isolated from the cellular and data networks, when it was received, and when it was examined. As covered in several chapters in this book, isolating a mobile device from outside networks is mandatory and should be done as soon as possible. Allowing a mobile device to remain connected can have devastating effects on the data within the device, ranging from altering the file metadata to deleting the entire file system.

When conducting a mobile device collection, the examiner is essentially working with a snapshot of the device data—a picture of the device from a time period leading up to the device’s seizure, which in most occasions is right around the time of the event. If a device connects to a network, the probability of data contamination is great and the entire time line, frozen in time by isolation, could be spoiled. The documentation must include this valuable information.

At the Scene If the examiner seized the mobile device at the scene, the documentation of the isolation technique will be straightforward. The examiner must make sure to include the steps taken at the scene to isolate the device and the state the device was in, along with date and time information when the device was isolated.

At the Lab If the mobile device was seized by someone other than the examiner, the examiner must indicate the state the device was in when he or she received it. This includes whether the device was powered on or off, inside a Faraday bag, powered on and in airplane mode, or, in some cases, powered on with no form of isolation.

If the examiner is receiving the device either directly from the field or from a property room, he or she must ensure that clear documentation has been received from the person who seized the device from the location. This information should indicate how the device was isolated (airplane mode, isolation bag), how the device was packaged at the site (Faraday box, bag, or container), and the date and time of the isolation. Sometimes this information is difficult to obtain, so the examiner must be diligent and contact the person who seized and isolated the device if this information has not been documented. If it has been documented, the examiner can refer to the report created by the person who isolated the device, which should be placed into the Supplemental Documents folder.

![]()

If a device is brought to the examiner powered on and not isolated, the examiner must immediately take steps to isolate the device using his or her standard operating procedure.

Whatever the case, the examiner must outline the details, indicating the removal of the device from the network, how it remained isolated from the network during the examination, and if it was not isolated, the circumstances as to why the device was not isolated. An examiner failing to include this information will often have to explain away the possibility of contaminated data, altered file dates, or other anomalies within the device file system.

Collection Methods

As covered in Chapter 10, examiners can use various collection methods to obtain data from a mobile device, ranging from an invasive chip-off to photographing the mobile device screen. Whatever the technique used, the examiner must outline in detail the way in which the data was collected.

If an invasive chip-off physical collection, JTAG collection, or ISP collection occurred, the examiner must document the reasons behind such a technical collection. Typically, these methods are used because gaining access to the mobile device using any other means was impossible—perhaps because the device was password protected, because the device had been destroyed by chemical or mechanical means, or because no mobile forensic solution supported the collection of the device’s internal file system.

In most cases, a mobile device will be tethered to a personal computer with a cable during the examination. This cable is the conduit between the software and the mobile device. Mobile devices communicate using protocols and commands that have been outlined throughout the book for both logical and physical collections. The commands used by mobile forensic software and other collection solutions travel via the attached cable, negotiating a backup of the device’s internal memory stores or files. This backup can occur either via these commands or after the installation of an application to the mobile device, such as an APK in Android. Of course, communication can occur via other means such as Bluetooth, but the documentation is generally the same; communication to the device using commands causes the device to deliver the requested data to a location specified by the mobile forensic solution.

In all cases, data changes occur within the mobile device, but the examiner must provide a detailed explanation of any system data changes that occurred within the internal store that was not user data. The examiner should be prepared to explain how this is known in case this information is challenged. The explanation of verification and validation does not need to be a part of the final documentation, but it should be a part of the examiner’s notes and knowledge base, since this information will surely be brought up in a trial.

An examiner must be confident in detailing the collection methods within the documentation because credibility of the process will often be tested. If an examiner has not documented the details of why an invasive method was or was not employed, why one software solution collected and displayed a piece of data that another did not, he or she may have to answer to the report audience. This information should be mandatory in the final documentation.

Collected Data

As you know, an examiner should not simply rely on the output from the mobile solution to document the collected data. The examiner must detail the main information within the body of the final document and there refer to the report or reports created by the tool. The audience does not want or need to delve into the thousands of contacts and SMS messages; they need a clear and concise view of the requested data, not a data dump they have to sort through.

The collected data portion of the report should include images and clearly defined, measurable details. If, for example, the UFED Touch 2 was used to complete a physical collection of a Samsung Fascinate SCH-I500 and the userdata.rfs and dbdata.rfs partitions were collected, the report should specify the time of the collection, the size of the binary files, and the overall hash of both binary files within the main body. If possible, and if the tool supports this information, the examiner should list the total number of files in the partition’s file system. This information can be valuable when describing the massive amount of data within a mobile device to the audience.

When possible, the examiner should detail the information that was extracted via the automated tool, indicating the number of items that were contained in each user data container and the pertinent information that was recovered for each. If possible, the examiner should include the file from which this data was recovered along with an overall hash of that file. This can ensure that another examiner can duplicate the results using the same file, even if he or she has to use another tool to complete the analysis.

Here’s an example of a statement that can be used when describing call history records:

500 Call History records were collected from the mobile device. The call history database was located within the file system at datacom.sec.provider.logsproviderlogs.db. A MD5 hash of the file was obtained: c7da421a8de57e813f947b713f676405. Of the 500 records, 212 calls were made to the mobile number of Ms. Smith and there were no incoming calls from Ms. Smith’s mobile number between the dates of June 1, 2015, and June 4, 2015. Of the 212 calls, 15 calls showed a duration of 5 minutes or less, with the balance indicating 1 minute or less.

The examiner should detail this information for all collected data from a mobile solution as well as information manually collected using advanced methods such as SQL queries or scripting.

When an examiner must use advanced methods, these methods do not need to be explained in detail within the document, but the collected data should include context. Context will help to set the stage for the audience on the process that was taken and the reason why the automated tool was unable to locate all of the important data. This data is often at the center of the audience’s attention because the automated tool “didn’t find it.” As you know, an automated tool not finding app data is a regular occurrence, primarily because of the plethora of available apps (more than 5 million in iOS or Android alone). This goes for free file parsing for deleted data from SQLite databases, file carving, and string searching. When using this type of analysis, the examiner should include a section of the report dedicated to outlining this material, apart from what the automated tools collected. This is particularly important when the collected information is relevant to the case requirements and outline.

The collected data portion of the document should reflect all the collected areas that contain valuable data, as requested or as part of the overall data picture. Also, a brief narrative should describe any collected data containers that are void of significant data:

Out of the 525 contacts located on the mobile device, the name Ms. Smith, her phone number, e-mail address, or other identifying information was not located.

If an examiner neglects to include information indicating that something was not located, this missing data is often questioned. Why did the examiner not indicate there was no information? What is the examiner trying to avoid? What other information might be left out? These are all valid questions. This section should be mandatory for the final report.

Tools That Collected and Analyzed the Data Usually, the examiner uses more than one tool to collect and examine the data: one tool is used to collect the device image, while other tools are used to parse and dissect the data. The document should distinctly outline the tools used to complete the collection of the image and ensuing analysis. This information should be documented in the collected data section in each area where multiple tools were used. Within the collected data section, examiners can add multiple subsections defined by the tool used, and any data that was analyzed is listed in each subsection. This is often the best method, because the information can be easily followed by both the audience and the examiner creating the report.

In the tools section, the examiner can list any discrepancies in the data parsed when using multiple tools. One tool may parse additional fields from a SQLite database that another tool did not, providing a different set of results. When this occurs, this information should be part of the documentation. Again, when this information is not documented, the examiner’s report can lead to serious questions on the use of the additional tools. As an examiner who has completed and reviewed hundreds of mobile device examinations and their data, I know that this will happen more often than not. Commonly, the differences in the data result from the queries the tools are using to collect the data from a SQLite database. By outlining this information in the report, an examiner will generally quell any potential challenges. This section should be mandatory for the final report, even if a single tool was used for collection and analysis.

What Does the Data Mean?

The final section of the main report will outline the key points of the case, what was requested, and the information that was located that supports the case. This summary area includes the opinions of the examiner based upon the facts of the case. This section should be supported by the collected data area and should not include any data not already mentioned. The conclusion area of the report should show the audience what the collected data means. Data from a mobile device is fact; it is a snapshot of information from the device’s internal store. This data can be confusing if an examiner does not provide a conclusion in the report.

Sometimes the data found within a mobile device does not include the particular information that was requested, or it may include information that contradicts the original hypothesis. This information should be emphasized in this section. An examiner should also use this section to educate the audience on the differences between the types of data collected. The examiner should be prepared to explain the multiple types of digital data to the audience—data on its own and in the context of the examination focus.

This section of the report is often the most powerful one, because it provides the big picture, an interpretation of the data collected. Whether multiple devices were collected or data was collected from a single event, including a collective interpretation of the data is recommended, if not mandatory.

Data on Its Own Reports are often spit out by automated tools as single investigations, and this data is interpreted as a singular event, which looks much different from data collectively analyzed. When a mobile device is the only piece of evidence requested and collected, the data is specific to that device only. Mobile devices are seldom used independently, however, and are instead used for communication either directly, with another mobile device, or via an intermediary medium such as a server.

Collective Interpretation Seldom is only a single device involved in a mobile device investigation. The examiner usually creates a report detailing the data collectively. An examiner should create subsections within the overall report that define the individually collected data elements, showing where the data was collected and what data was collected from each piece of evidence as an individual exhibit. This enables the audience to see the data collected from multiple sources, such as mobile devices, cloud stores, computers, servers, and flash media, individually. This is important, particularly if one piece of evidence contains unique information not found in the other evidence.

The conclusion should contain the examiner’s collective analysis of all the data contained within each device as it relates to the others. The examiner should show relationships among the collected data based on time lines, conversations, and any other artifacts that show collective association.

To Include or Not to Include

Examiners should know what information will be distributed, what will not be distributed, and what will be archived. The documentation should present a list of the included materials to introduce the audience to the contents. This information can be in a README.txt file included with the distributed media. The reader can use this information to identify and refer to the material within the main report. Usually, the materials the examiner includes with the report are governed by the SOP developed by the examiner’s sponsoring agency or company.

Some items should not be distributed in the completed report—that is, items that do not provide value to the audience. However, this information should always be available if requested. No materials should be removed or deleted from the case until directed to do so by the SOP or other authority. Following are some basic suggestions on what to include and what not to include.

Include Media, Documentation, and Screenshots

All media extracted from the mobile device that is part of the case should always be included in the evidence folder within the distributed media. Any pictures, video, and audio taken of the evidence by the examiner or subjects seizing the data do not need to be included. (See the upcoming section “Do Not Include Forensic Evidence Images.”)

References to screenshots of software or the analysis can also be made, though the actual screenshots themselves need not be included in the main report. Because screenshots are created during the investigation, either during the collection of document settings or during the analysis of document settings and data, references to the screenshots should be included on the distributed media. The screenshot files should be clearly named and referenced in the main report. The actual screenshot files should be placed in the Supplemental Documents folder in a subfolder named Screenshots. The reader can then reference this material, if needed, to support the text in the main report.

Written documentation outlining the process should be included in the case report, clearly indicating the existence of the media. However, media files such as notes do not need to be included unless requested. (See the upcoming section “Do Not Include Examiner Notes.”) These files should be saved and archived so that they can be produced if needed.

Include References

It is often important to include reference material for the audience, such as common mobile device terms and acronyms with understandable descriptions, infographics showing the number of mobile devices collected, graphics showing the way a mobile device communicates with a network, and breakdowns of data as appropriate. A picture may convey the message better than text. This, of course, will be directed by the type of investigation the examiner is conducting.

For common mobile forensic terms, the examiner should compile a list to be included within every report. As mentioned, the examiner should always strive to avoid technical jargon. This information should be included in the Supplemental Documents folder and referred to within the main report text, if needed.

When imagery or details such as infographics or created images outlining the decoding of an artifact are included, the image should be referenced to support a written description within the main documentation. The actual image should not be a part of the main report. This information should be contained with the Supplemental Documents folder.

Do Not Include Examiner Notes

Notes compiled by the examiner, such as the formatted note template discussed earlier, should be used by the examiner to compile the final report and to support any challenges to the reception, condition, and handling of the evidence. Unless the notes are required or requested, they can be left out of the main report. However, all notes and material used to compile the final report should be archived, along with the data and the final submitted report. Each page of written material compiled by the examiner should contain a signature with a date. This security precaution can assist both the examiner and audience if the authenticity of the documents is challenged.

Do Not Include Forensic Evidence Images

The examiner should not include the actual forensic images of collected devices used during the investigation and subsequent analysis in the main report. Forensic images are used for collecting intelligence, not for explaining or detailing the evidence recovered. Instead, the original forensic images should be archived with all other data and documents compiled and created for the case. The images will be maintained as outlined in the agency or company SOP.

The forensic images, however, can be requested by the audience if it is determined that the evidence will be examined by a second examiner. At that time, the forensic images should be copied and placed in their own storage media and given to the appropriate persons.

In some cases, if data contained within the image includes criminal images (such as child pornography) or sensitive company information, the images are generally not released for obvious reasons. In such cases, the audience requesting the images often views the information at a designated location; this maintains the legality and sensitivity of the evidence, since distributing or making copies of this evidence could technically be a crime. The original examiner should inform the reader of the sensitive content to avoid questions as to why the forensic images cannot be disclosed.

On December 1, 2017, two new Federal Rules of Evidence were added to FRE 902: Rule 902(13): Certified Records Generated by an Electronic Process or System and Rule 902(14): Certified Data Copied from an Electronic Device, Storage Medium, or File. Rule 902(14) pertains the most to the forensic examination and production. FRE 902 lists the evidence that is self-authenticating and outlines the items that do not need additional authentication to be admitted into evidence. These rules were added because of the large amounts of electronically stored information (ESI) used in trials today. Bringing in experts to testify as to how a forensic tool works to extract data, or to authenticate the text message existing on the telco’s server, or to explain how a page on a Facebook account is extracted and produced is, in fact, valid, but doing so proved to be overly time-consuming for the courts, and the cost of hiring these experts (if one could even be found) was difficult to gauge.

The most important rule to the mobile forensic examiner conducting the extraction is FRE 902(14):

Data copied from an electronic device, storage medium, or file, if authenticated by a process of digital identification, as shown by a certification of a qualified person that complies with the certification requirements of Rule 902(11) or (12). The proponent also must meet the notice requirements of Rule 902(11).

In other words, if the process can be authenticated by a hash that can be verified as consistent, and the person who conducted the extraction and hashing is competent in using the tool and processing and has certified the results, the data can be admitted as evidence without additional authentication from another party.

Becoming a Mobile Forensic Device Expert

This book is devoted to the examiner’s journey to becoming a mobile forensic expert. Becoming a mobile forensic expert has nothing to do with certifications received for performance on aptitude tests, subjective practical exams, or other written tests. The word journey best describes how becoming an expert should feel.

Unfortunately, a lot of individuals who are starting out in the field of mobile forensics would rather it be a called a sprint. Most look for certifications as a quick way to find a career and believe that a certification will somehow propel them into becoming an expert. It is this belief that has cast a shadow on a field that is growing at breakneck speed, where the number of examiners considered experts has flatlined.

The word certification has been mentioned throughout the book. Certifications currently come in two main flavors: vendor-created and tool-based. A vendor-created certification “certifies” that the examiner knows how to use the vendor’s product; this is not the same as being an expert in mobile forensics. A tool-based certification indicates that the examiner has completed the necessary steps to use the vendor’s product; it may simply be a label to attach to a name on a calling card.

Currently, mobile forensics lacks a general certification, which would expose an examiner to processes and procedures, various tools, a variety of methods, and a core set of proficiencies. This should be changing soon, however, with the addition of a general mobile device certification board at the International Association of Computer Investigative Specialists (IACIS). However, an examiner does not become an expert in the field merely by getting certified—it takes a lot of hard work.

A mobile forensic expert is an examiner who never relies completely on an automated tool or process. This examiner resists the temptation to click the “Easy” button in search of the truth within an ever-growing amount of data. The expert examiner is never satisfied but will fine-tune the examination processes and procedures whenever possible. The mobile forensic expert will spend countless hours exploring in an effort to uncover massive amounts of data, including never-before-found artifacts.

The ability to locate data using manual techniques does not, on its own, define a mobile forensic expert, but it is part of the equation. Once the expert examiner locates this data, he or she will research and test to arrive at a conclusion as to why this data is written to the device’s storage area. Furthermore, the expert will seek to comprehend the processes that took place or that needed to occur for this type of evidence to be written to the device’s storage. Then the examiner can determine what this data might mean to the investigation—by looking at the totality of the evidence, not just a located artifact.

The road to becoming an expert is full of switchbacks and curves, and examiners must navigate undocumented terrain. Experts do not wait for the instructions; they often write the instructions themselves. One of the most critical aspects of the investigational process is peer review. When instructions, procedures, and methods are created and tested, the examiner should allow for the review of the process and artifacts. This critical stage will not only maintain the processes’ integrity but will also help processes continue to improve. Changes are needed to maintain the most up-to-date and relevant procedures consistently in the ever-changing mobile device environment.

In 1990, psychologist Anders Ericsson determined that 10,000 hours of repetition was the secret to becoming an expert. However, how the 10,000 hours are spent matters. To become an expert means to practice, conform, and evolve to refine the discipline, constantly updating and improving the methods. For a mobile forensic examiner, this includes not only collections but also research, documentation, and testimony of findings.

The legal world often describes a forensic expert as an individual who provides an opinion more knowledgeable than that of a typical layperson, based upon specialized knowledge or training. The expert’s opinion is deemed more valuable because it is based upon scientific, technical, and specialized training, education, or experience.

Obtaining testimonial experience of the findings of an examiner’s mobile device investigation is also extremely important. Whether it be simply explaining the findings to a council, board, magistrate, judge, grand jury, or state or federal juries, providing testimony is critical. This type of practice is essential for an examiner on his or her journey to becoming an expert in the field. Providing testimony will help an examiner discern the value of meticulous research and conscientious documentation—either good or bad. During testimony, the examiner will be expected to support any opinion with facts presented in his or her written documentation, as well as evidence uncovered. If an examiner cannot support his or her examination with insight into the data’s existence within the mobile device by documentation or testimony, the data is difficult, if not impossible, to use in a case.

By investigating the mobile device, formulating the documentation, and grasping the principles outlined in this book, the examiner will have the best chance of success. The more an examiner is able to testify to the findings uncovered in a mobile device examination, the better the testimony will be, and the better the examinations of the data will become.

Importance of a Complete Collection

A complete collection is one of the most important considerations for a mobile forensic examiner. A complete collection of a mobile device contains a file system, not just an outputted report with data pulled from the mobile device. Of course, in some situations, an examiner will be unable to produce a collection that includes a file system because of limitations of the mobile device or supported software. However, if the mobile device can be collected to include a file system, which is possible with the majority of today’s devices, there is no excuse not to include a file system in each collection.

Unfortunately, mobile forensic examiners often need to collect as much information as possible in the least amount of time. As a result, software vendors often highlight their product’s collection speed over other features. But this speed can also result in a partial collection or a partial parsing of the data. Some examiners contend that there is not enough time to complete a collection that includes the file system, but an expert examiner’s logical iOS collection must include the entire file system. An expert is not the examiner who merely pushes a button to extract data from the mobile device.

Conforming to Current Expectations May Not Be the Best Approach

Based upon misconceptions of the process and procedures along with the methods of collection, mobile forensics has sometimes been compared to magic. Many software vendors early on believed that ease of use, limited access to device file systems, immediate reporting, and a simple output was what the mobile forensics community needed. The tool would be so easy to use that little or no training would be required. This backward approach to mobile forensics continues to be the current expectation for examinations across the globe.

This book was written to inform the mobile forensic examiner that by conforming to this type of collection expectation, an examiner becomes a person who simply presses a few buttons and smiles when the data materializes on the screen. This type of collection shows zero regard for how that information was obtained, where it was obtained, and whether or not additional information was collected by the tool. This conforming attitude among examiners will continue unless more examiners seek to become experts in the field of mobile forensics.

Today’s mobile forensic examiners must realize that thousands of files are available within a mobile device’s file system, and these are often viewable using free open source tools. These files and file systems represent digital gold to the examiner who knows what to look for. An examiner today should be digging into these areas, creating automated scripts, researching the various file types, and discovering new methods. Mobile forensics expert examiners are pioneers who know that the forensic processing of a mobile device and all the associated data should include the application of the methods and theories expressed in this book, instead of conforming to conventional mobile device collection processes.

Additional Suggestions and Advice

This book has provided solid techniques and approaches to mobile device forensics, plus real-life examples from the author’s many years of being a practitioner in the field. It has offered suggestions on how to make mobile device collection and analysis a process that can be duplicated when needed.

An examiner should never look for a faster way to perform a collection or complete the parsing and analysis of the collected data. Instead, an examiner should look for the best methods and means that will cost the least amount of time in explaining what was done, or not done, during the examination. Once a report of the examination has been distributed, a good measure of the work can be indicated by the questions that follow. If an examiner shortcuts the examination, the odds are good that he or she will face multiple challenges and questions by the readers and audience.

The following sections provide some additional suggestions for the examiner who seeks to become an expert in the field of mobile forensics.

Constant Research and Testing

An examiner must stay up-to-date with the rapidly changing technology, continuous updating of mobile device software, and massive influx of mobile forensic solutions and features. The diverse and ever-changing mobile device landscape creates a challenge to the dedicated mobile device forensic examiner.

Apple sales surpassed those of Samsung in 2016 but fell behind in 2017 when the Samsung Galaxy 8 was released. In 2017, Samsung again maintained that 1 million devices were being sold each day, and Google reported in 2015, and again confirmed in 2017, that there were more Internet searches completed using mobile devices than personal computers. Moore’s law suggests that technological growth doubles every 18 months, but at times the exponential growth of mobile device technology exceeds this estimate. This is compelling information, but unfortunately mobile forensic examiners and software solutions are having a difficult time keeping up. An examiner must take it upon himself or herself to research continually the various devices coming to market, the newest file systems, and the trending apps that will surely make their way onto the next mobile device submitted for analysis. An examiner who relies on forensic solutions alone will only be as good as the tool that he or she is using. By staying in pace with the technology, an examiner will be adapting, practicing, and gaining more time toward the 10,000 hours needed to be an expert in the field.

More Mobile Forensics Information

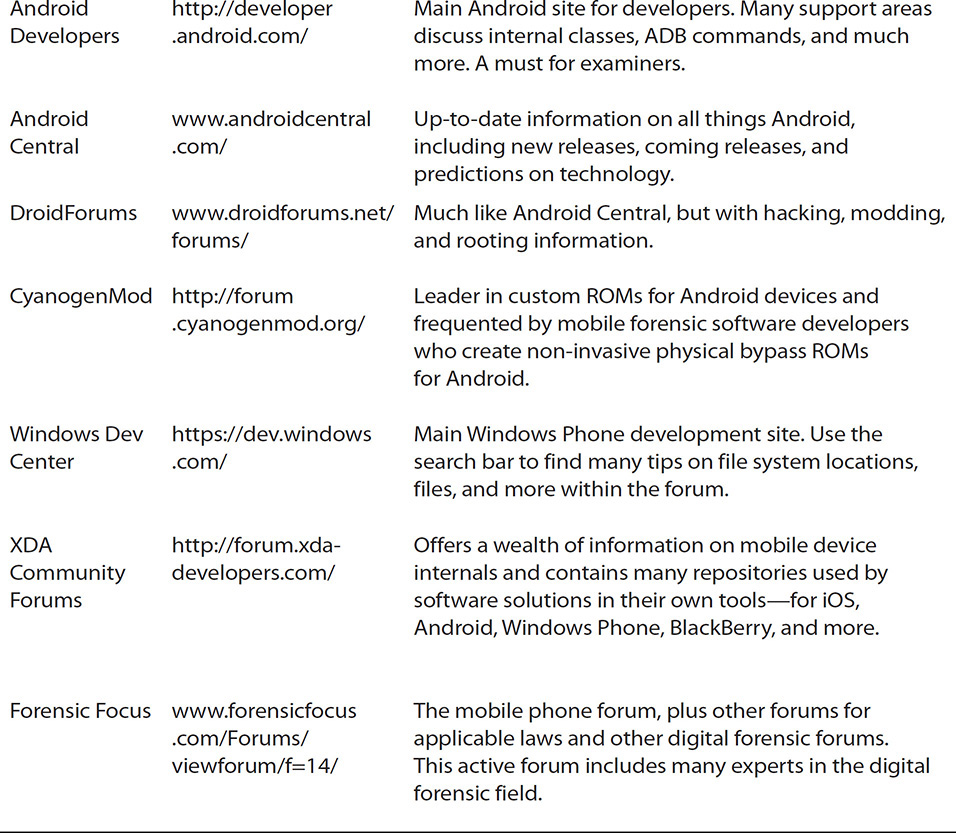

Compiled in Table 17-3 are web sites where an examiner can find an abundance of information to assist on the road to becoming an expert examiner.

TABLE 17-3 Web Sites with Helpful Information for the Examiner

Chapter Summary

The path to becoming a mobile forensic expert is an arduous one that does not depend on quick solutions. An expert is defined by his or her successful presentation of abundant facts, knowledge and training within this specialized field, and constant need for growth within the discipline.

The examiner presents his or her discoveries in a fact-filled document to a predetermined audience—ranging from a single individual to a judge and jury. A skilled examiner prepares the final document to suit a multitude of readers by creating a report that is structured to introduce the reader to the investigation’s five W’s, present the process workflow, and then define the conclusion reached based upon the evidence. As this chapter explains, an automated report generated by a forensic solution does not provide the big picture. The automated report can contain exceptional data, but it provides no context. A reader needs context to see the big picture of the captured data, and the final document created by the examiner provides this context.

Collecting valuable data from a mobile device and creating a tremendous final document doesn’t make an examiner an expert by any means. Becoming an expert in any field requires that an individual constantly adapt to the changing environment, to seek new ways to solve problems, practice the craft, redirect the course if needed, and become immersed in ideas to improve the discipline. Becoming an expert is not about becoming better than someone else, but involves challenging yourself to become the best you can be. The only way to accomplish such a lofty goal in mobile forensics is to be vigilant in training, research, and testing of new methodologies and ideas. An expert is not made with a certification document, but through hard work and dedication.

The road to becoming an expert in the field of mobile device forensics will be long and often filled with potholes. However, along the way, the examiner will meet many other great examiners and practitioners, and those meetings and conversations will show the examiner the benefits of hard work and perseverance.