CHAPTER 5

THE POWER OF SYNTHESIS

Cultivate Creative Integration

Comparing the capacity of computers to the capacity of the human brain, I’ve often wondered, where does our success come from? The answer is synthesis, the ability to combine creativity and calculation, art and science, into a whole that is much greater than the sum of its parts.1

—Garry Kasparov, former World Chess Champion

In an economy founded on information abundance, the lion’s share of value goes to those who can synthesize a multitude of elements to comprehend the whole, build expertise, make better decisions, perceive opportunities, and keep ahead of machines.

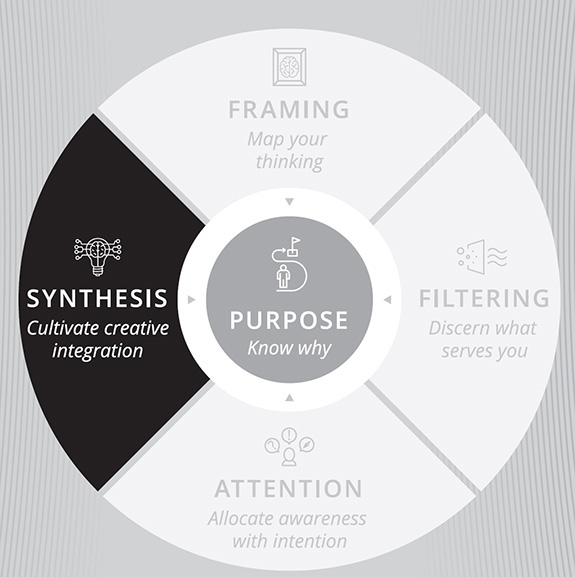

To create a wellspring of synthesis we need a foundation of openness to new information, on which we build our capacities to make creative connections and integrate disparate, sometimes paradoxical ideas. These enable us to continuously enrich our mental models to become more complex and useful. Rounding out our capabilities, we can learn to nurture the states of mind in which synthesis is most likely to occur.

The final application of our capacity for synthesis is better decisions. In an exceptionally uncertain world, the best outcomes come from decisions that let us learn, refine our assessment of probabilities, and withstand contrarian thinking.

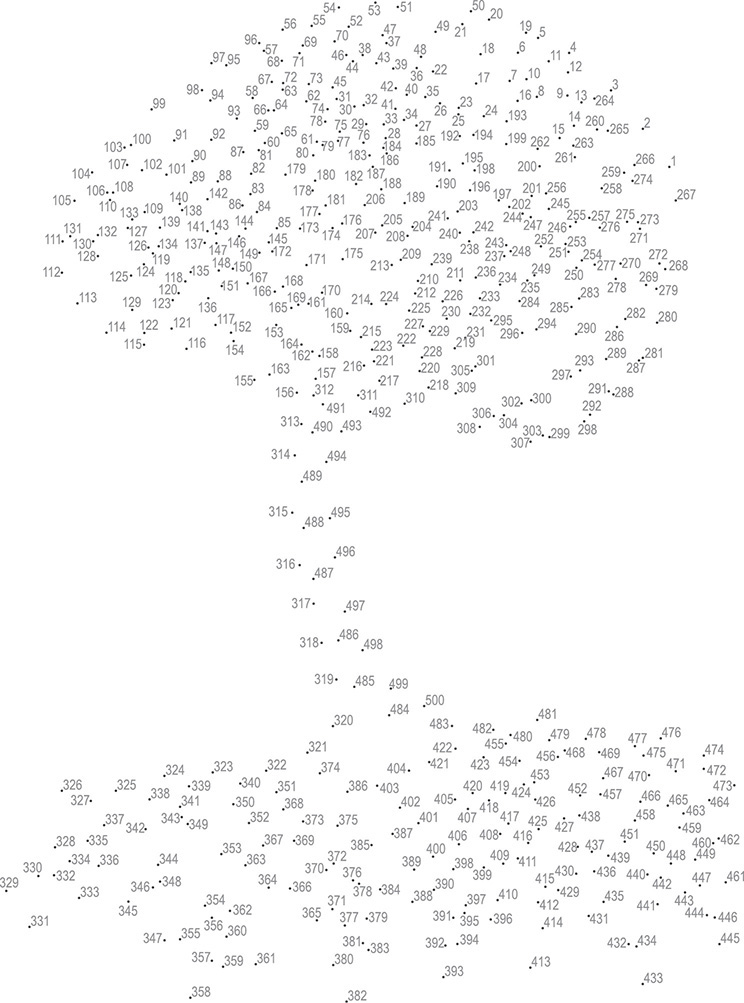

In our formative years our parents tended to our cognitive development by giving us educational books. You were probably given a join-the-dots figure, in which you connected dots in sequence for a hidden image to emerge on the page. Drawing lines between consecutively numbered dots is fairly easy for a child. As you drew successive lines you tried to work out what the image might depict, until in one moment you finally discerned the pattern being formed.

If you want to experience this with a slightly more advanced example, try joining the dots in Figure 5.1. As you progress, try to discern the pattern, noticing when you recognize the concept portrayed, probably in a single moment.

FIGURE 5.1 Connect the Dots to See What Emerges

For adults, “connecting the dots” refers to pulling together a disparate set of information, occurrences, issues, or events to reveal concealed patterns and make sense of what at first blush appears to be unrelated. This is often experienced as an instant of insight and clarity, when the relationships are suddenly obvious and the entire picture comes into focus.

The ultimate reason to engage with information is to understand the world better, and thus learn how best to create what we desire. Knowing many facts is useless. We need to build a lattice of meaningful connections, drawing together what we encounter into a holistic view that enables intensely productive action.

Synthesis is precisely the antithesis of analysis. To perceive the whole, we must necessarily transcend reductionist, overly rational thinking. We need to deliberately cultivate our subtle, often evanescent ability to synthesize today’s incredibly complexity by tending to what is below the surface of our minds as much as to our conscious thinking.

Synthesis and Human Progress

Humans are born inventors. Our cumulative efforts have brought us from the stone age to the wonders of today’s civilization. The inventions and advances that have shaped that extraordinary journey have not come out of thin air. Every single one has built on ideas, research, and insight that came before.

All innovation stems from connecting existing ideas in new ways.

The highly eccentric chemist Kary Mullis won the Nobel Prize in 1993 for his breakthrough origination of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique. Speaking about how he came up with the idea, Mullis said, “I put together elements that were already there, but that’s what inventors always do. You can’t make up new elements, usually. The new element, if any, was the combination, the way they were used.”2 His act of synthesis in inventing PCR is still helping people millions of times every day through its application in the most accurate Covid-19 tests.

In his book A Whole New Mind, Daniel Pink argues that we have already moved beyond the information age into the conceptual age, meaning our skills must also evolve. “The future belongs to a very different kind of person with a very different kind of mind—creators and empathizers, pattern recognizers, and meaning makers,” he says.3

Among the aptitudes Pink puts at the center of success in this era is what he calls “symphonic thinking.” “Symphony . . . is the ability to put together the pieces,” Pink writes. “It is the capacity to synthesize rather than to analyze; to see relationships between seemingly unrelated fields; to detect broad patterns rather than to deliver specific answers; and to invent something new by combining elements nobody else thought to pair.”4

As complexity increases, it becomes harder to bring into harmony the cacophony of incessant noise that surrounds us. Synthesis is moving to the center of value creation. It is a capability that we can—and must—actively develop.

Outcomes from Synthesis

Many people “cannot see the forest for the trees,” seeing details but never the whole. Global competition and advancing machine capabilities are consistently tearing down the value of those people who see only minutiae, and steadily increasing the value of those who grasp higher-level systems. Those who are adept at synthesis will be masters of the universe. There are five primary outcomes from developing your capabilities of synthesis:

1. Understanding. Life is a process of sense-making, literally making sense of how the world works, what our place in the world could be, and what things mean. As individuals wending our way through life and work, our primary intent must be to understand the nature of the world and our area of expertise. Everything else flows from there.

2. True expertise. Being an expert is of course far more than knowing profuse details about your domain. Pulling together the many elements of your area of expertise, to have seen them from many angles, to see how they all fit together, is at the core of mastery. This is why you cannot be a true expert in any subject without having spent years in the space. Perceiving the whole is a prerequisite for expertise.

3. Better decisions. All significant decisions are complex, with multiple factors, many inherently unknowable. Any choice of action made on the basis of individual elements will likely be flawed. Decisions that are based on comprehension of many factors, the broadest possible context, are far more likely to be successful.

4. Seeing opportunities. As long as the universe is changing, there will be opportunities. Given today’s pace of change, there are more possibilities than ever before. At the same time, perceiving and assessing them becomes far more difficult, given multiplying variables and uncertainties. Being able to see the whole not only makes opportunities more apparent but also makes evaluating them far more tractable.

5. Keeping ahead of machines. AI has transcended expert human capabilities in a host of domains, including recognizing images, diagnosing a range of diseases, and playing virtually every game ever created. Yet humans’ ability to synthesize disparate information from disconnected fields to generate understanding, new perspectives, and better decisions far exceeds the capacity of any AI system we can envisage for the foreseeable future.

“We are drowning in information, while starving for wisdom,” affirmed biologist E. O. Wilson, who has been described as “Darwin’s natural heir.”5 “The world henceforth will be run by synthesizers, people able to put together the right information at the right time, think critically about it, and make important choices wisely.” If you want to run the world, be a synthesizer.

The outcome of our synthesis is reflected, ultimately, in our mental models. All our thoughts and actions stem from our conceptions of how the world works.6

The Models in Your Mind

Warren Buffett, the “Oracle of Omaha,” is the front man of Berkshire Hathaway, whose careful investments have consistently outperformed the market for decades, growing in value over one–thousand-fold over the past 40 years. Yet at the company’s annual shareholders meeting, sometimes described as the “Woodstock of Capitalists,” attended by 40,000 investors, the event is cohosted by his trusted partner from the very first days of the company, Charlie Munger.

Munger is a careful thinker, considering information from all angles before making investments. Among financial market players he is the apostle of developing sound “mental models” for your life and decisions, with the book compiling his thoughts, Poor Charlie’s Almanack (available only in hardcover for $120), pored over by investors for insights into how his mind works.

I think it is undeniably true that the human brain must work in models. The trick is to have your brain work better than the other person’s brain because it understands the most fundamental models: ones that will do most work per unit.7

—Charlie Munger

Cognitive psychologists have long used the idea of mental models—representations in our mind of how the world works—to understand how we think.8 From the moment we are born, we begin to build models in our minds, starting with how our parents respond to us and the mechanics of the world, before moving on to more complex situations. All our behaviors and every decision we make are based on these models, which tell us what we expect to happen as a result of our actions.

Implicit Wisdom

Many use the term “mental model” to refer to simple frameworks or heuristics that help us to think and make decisions. One example is Occam’s razor, which in essence says the solution with fewer elements or assumptions is more likely to be true. It can very handily be applied to many conspiracy theories. Some believers in a flat earth propose that Australia doesn’t actually exist—it is a hoax carefully created to deceive us, with those who are supposed to be Australians in fact actors paid by NASA. While this is conceivably true (unless you happen to live in Australia), the myriad activities that would be required to maintain this appearance makes this unlikely, to put it mildly.

Thinking tools such as Occam’s razor can certainly be useful, but they do not describe how we actually think. The reality is that we always make decisions based on the entirety of our life’s experience and how we have interpreted it. We might use some tools and frameworks to help our conscious decision-making process, but the truth is that our mental models are never fully explicit or understood, even by ourselves.

We will always know more than we can articulate.9 If we can say it or write it, it becomes information, available to others. But writing or trying to capture in software what we think doesn’t make us redundant. We are the sum of our life’s experience, able to gain insight and act effectively in situations we have never before encountered. More than looking for simple, reducible rules of thumb to assist our thinking, we should focus holistically on our models as expressing the entirety of our cognition of the world and how we think and act. We will never be able to fully surface or understand our mental models. Yet we can work to improve them, make them more useful, and most importantly, evolve as new information becomes available.

The Wellspring of Synthesis

There are five foundational elements that support our ability to excel at synthesis: openness to ideas, creative connections, integrative thinking, richer mental models, and states of mind for insight. Figure 5.2 depicts how these elements build up from the underlying principles step by step to form an abundant fountainhead of synthesis. Each of these capabilities in turn flows back down to feed the ones below. The synthesis that emerges supports our final outcome: the decisions and actions that are most likely to achieve our goals.

FIGURE 5.2 The Wellspring of Synthesis

We will delve into each of these elements in turn, beginning from the foundations. The base of the wellspring of synthesis is the simple act of being open to new possibilities and ideas. When today is different from yesterday and tomorrow will be different from today, you cannot rely solely on ideas and experiences of the past and must be receptive to evolving your thinking.

Openness to Ideas

The science of personality types began in 1917 when Katharine Briggs became intrigued by the seemingly unlikely romance between her only daughter Isabel and the young lawyer Clarence Gates Myers. She sought to understand their compatibility and retain her relationship with her daughter. Finally stumbling across Carl Gustav Jung’s book Psychological Types, she worked with her daughter to create the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator.10 Over a century later the test is still widely used despite being superseded by superior models.

Researchers have since exhaustively explored and consolidated the full range of human psychological variation into a set of five dimensions, now commonly called the OCEAN “Big Five” personality traits: Openness to experience, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism.11

Of particular interest to us is openness to experience. This can also be framed as openness to new information: our ability to adapt by noticing that the world has changed, accepting rather than rejecting relevant signals, and as a result, changing our outlook, opinions, and actions. In a swiftly evolving world, people who are less open to new information are significantly disadvantaged, mired in fixed thinking. Those who are open to new ideas and use them to improve their mental models will thrive.

In a world of accelerating change the open-minded have a powerful advantage.

The empirically demonstrated value of higher openness to experience is massive, including improved job performance, probability of being promoted, and likelihood to become and succeed at being an entrepreneur.12 Other demonstrated benefits include increased life satisfaction and reduced risk of cognitive decline with age.13 Not least, it is associated with our ability to perceive salient patterns in a chaotic environment.14

Most people think they are open-minded, with 95 percent rating themselves as more open than average.15 This clearly cannot be true. What distinguishes true leaders and experts is that they work to overcome their inbuilt biases to continually evolve their thinking.

For a long time, psychologists observed that people’s personality traits do not usually change substantially over time. However, more recent studies have focused on those who intentionally strive to shape their personality, finding that we can with volition and carefully designed interventions evolve how we engage with the world.16 If we choose, we can change our personality to make us better adapted to our environment and lead better lives.

There are a variety of proven ways to increase our openness. Exposing ourselves to cultural experiences such as art galleries, museums, and live music performances leads to increased openness to experience, according to a Dutch study of over 7,000 people. This inclination feeds on itself, leading to greater desire for cultural experiences.17 A range of training courses have been developed that successfully increase openness.18 However, simply resolving to enact an attitude of being more open for its benefits is often the most effective path.

A recent explosion of research on the impact of psychedelic drugs has uncovered their positive potential in treating a range of maladies, including addiction, anxiety, and depression. Studies on the use of MDMA in the treatment of PTSD and the effects of psilocybin, the active ingredient in “magic mushrooms,” showed their therapeutic value was achieved largely through effecting a lasting increase in openness to experience, itself made possible by being receptive to new approaches.19 Tim Ferriss reports that “the billionaires I know, almost without exception, use hallucinogens on a regular basis,” to help them “ask completely new questions.”20 Be aware that this path is not for everyone; there can be significant risks from taking these substances. The studies mentioned were all run by trained therapists in carefully designed environments; this is not a recommendation to take illicit drugs.

The key point to take away is that openness is a foundational driver of success. As the world accelerates this will become even more true. Critically, you can choose to increase it. We should, of course, be aware that there is such a thing as too much openness.

Balancing Openness and Credulity

Have you seen the man in the moon? Magnetic lava flows below the lunar surface have created what for centuries many European cultures have seen as the eyes and mouth of a man. However, next time the moon waxes, look for the rabbit in the moon. East Asian cultures and some indigenous American peoples see a rabbit on our satellite’s surface, and once you’ve seen it, you are likely to see it again every time you gaze at the full moon.

These are simple examples of apophenia, the profoundly human tendency to see patterns where they do not exist. As we discovered in Chapter 2, humans are essentially pattern recognition animals: we perceive patterns so we can respond effectively to the world. The old proverb tells us that “when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” Our extraordinarily developed pattern-recognition capabilities mean we tend to see patterns in everything, whether they are real or not. This is evident in every aspect of human society, not just in conspiracy theories and quirky cold remedies, but also in our interpersonal interactions and often even business strategies.

The patterns we infer, consciously or often unconsciously, become part of the mental models we use to guide our lives, so we need to be prudent in assessing whether what we believe we see is founded in reality. We must be open to possibilities but also critical in assessing even our own perceptions and ideas. This is perhaps the most central of the many paradoxes we must reconcile to prosper in a deeply complex world. It is up to each of us to negotiate daily Carl Sagan’s exhortation to balance an expansive openness to new frames of thinking with intense skepticism.

Being open to new information, albeit judiciously, is the starting point. The next step is forming links between fresh ideas and our existing universe of thinking. We need to go beyond the obvious to identify useful associations, seeing not just the subtle but also the inspired connections.

Creative Connections

When scientists set out to measure creativity, they usually use tests of divergent thinking or remote association. These assess how obvious, unexpected, or diverse the concepts generated from a given starting point are. Some people have let themselves become sadly predictable in their thinking. Others are deeply original and innovative in the connections they bring to life; they are the creators in our society.

All synthesis is creative, and all creativity entails synthesis.

Perceiving obscure links between disparate ideas is a deeply creative act. The knowledge embodied in the frameworks you built in Chapter 2 came from identifying connections between ideas. The quality of your thinking will be vastly improved if you tend to notice quirkier yet still meaningful associations. Fortunately, you can develop the priceless gift of seeing connections.

Keith Johnstone, widely regarded as the godfather of improvisational theater, often called impro or improv, sees adults as “atrophied children” who have lost the ability to play and communicate directly. He believes that we are all exceptionally creative, it is just that capability has often been stifled in our upbringing and social conditioning.21

Improv requires consistent spontaneity, keeping the skit unfolding whither it may go. Participating in improv lessons can do wonders for our ability to transcend our internal censors and make inspired connections. In my twenties I took improvisational theater classes, which definitely helped my personality and ideas to flow more freely. Alternatively, you can find in Johnstone’s wonderful book Impro many fun and formative games you can play with friends or your children. A simple example is word-at-a-time, in which a group makes up a story, each person in turn swiftly providing the next word in the tale.22

Before becoming CEO of Twitter, Dick Costolo studied with Chicago’s famed Second City improvisational theater troupe, where actors such as Steve Carell and Tina Fey also trained, later applying what he learned to his corporate leadership style.23 Renowned Harvard Business School professor Rosabeth Moss Kanter uses improvisational theater as a compelling metaphor to describe how outperforming companies approach strategy.24

There are a range of other tools we can use to open our thinking to potential associations. Thinking about or being around people who are unlike you, whether in dress, attitude, or behavior, what researchers describe as “deviancy cues,” has been shown to stimulate more creative thinking.25 The more palpable workplace diversity, the greater the stimulation to innovate.

Psychological distance primes breadth of thought. Spending a moment thinking about places that are far away or what might happen in the distant future engenders big-picture thinking, helping you discern what’s important.26 You can deliberately practice divergent thinking. Many facilitators use decks of cards that present a set of highly diverse concepts. They task participants with generating connections from the issues they are grappling with to the ideas on the cards, sometimes resulting in breakthrough ideas. You can buy these sets of cards or make your own, exercising your ability to make more expansive mental connections.

Reinforcing Variability

The behaviorist B. F. Skinner proposed that all human behavior comes from conditioning, with consistent rewards resulting in predictable behavior. The backlash to this mindset led a generation to shy away from reinforcing human behaviors, feeling it made us akin to Pavlov’s dogs that salivated on the ring of a bell.

One of Skinner’s graduate students at Harvard, Allen Neuringer, wondered whether reinforcement could encourage variable rather than consistent responses. Through a lifetime of research, he clearly demonstrated that you could train both animals and humans to generate highly unpredictable responses. Earlier studies had shown that dolphins could be encouraged to enact multiple behaviors never before observed in the species, such as an aerial corkscrew.27 In his relentless self-experimentation, Neuringer used conditioning feedback to mentally generate random numbers, something previously thought impossible. A wide range of other experiments have verified that we can reinforce in ourselves creative, divergent responses.28 We can positively shape our thinking patterns.

You can choose to make divergent, unpredictable thinking a habit.

The highest level of creative association is linking ideas that seem to be not only unconnected, but in fact contradictory. As novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald observed, “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.”29 In an exceptionally complex world we need commensurately sophisticated mental models. This means they are increasingly likely to encompass what appear to be paradoxes.

Integrative Thinking

Sporting two faces looking in opposite directions, Janus was the Roman god of beginnings and endings, doorways, transitions, and polarities. The first of January, the month bearing his name, is both an ending and a beginning, representing opposites combined into a unity. The capacity for integrative thinking at the heart of synthesis is at its most creative and powerful when uniting paradoxes and polarities.

Life at its best is a creative synthesis of opposites in fruitful harmony.

—Martin Luther King Jr.

Paradoxical thinking is a skill you can develop that turns out to have manifold benefits. The Red Queen instructed Alice that with practice you can believe in impossible things. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day,” she said. “Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”30

A study by Ella Miron-Spektor, now a professor at leading business school INSEAD, tested the outcomes of this practice, confirming “the positive influence of paradoxical frames on creativity,” reporting that those primed to think of paradoxes, “increase exploration, sensitivity to unusual associations, and generation of new associations.”31 A follow-up study by Miron-Spektor showed that employees in a large American company who had a “paradox mindset” were seen by their managers to be more innovative and perform better in their roles.32

Many of the most valuable innovations in business stem from pursuing paradoxical objectives, such as simultaneously making things more profitable and better for the environment, or cheaper and higher quality. When Mother Teresa had a heart attack in 1984, specialist Dr. Devi Shetty took care of her, becoming her physician for the last five years of her life. She inspired him to turn his skills to helping the poor.33 He set out to provide the highest-quality medical attention at the lowest possible cost, serving anyone who needs care irrespective of their ability to pay. He founded what became Narayana Health in 2000 with a 300-bed hospital in Kolkata. The organization has now grown to 46 healthcare institutions with over 6,000 beds, generating a market capitalization of well over $1 billion. Its heart surgery procedures have by some measures better health outcomes than US hospitals, with heart bypasses delivered at 2 percent of the cost.34

A study of 22 Nobel Prize winners showed they all demonstrated “Janus thinking,” which the paper’s author defined as “actively conceiving multiple opposites or antitheses simultaneously.” Obvious examples include Niels Bohr’s epiphany that quantum objects can manifest either as waves or particles and Einstein’s reconciliation of Newtonian gravity with relativity, which he described as “the happiest thought of my life.”35 Discontinuous scientific progress is almost always through bold synthesis of domains that have been previously considered distinct.

The very phrase “thriving on overload” represents a paradox. Through this book we have examined some of the many paradoxes we must successfully integrate on this path, including openness and discernment, detail and big picture, clarity and seeking, and many more. As you work to develop your capabilities for success in our chaotic world, be sure to apply a paradox mindset.

In improvisational theater, a central principle is that you never negate what you are offered; you always take it and build on it, wherever that might take you. It is never “no” or “but,” it is unfailingly “yes, and.” This attitude is intrinsic to creative integration, recognizing that even opposites can be reconciled. We can inculcate in ourselves an attitude of integrating all worthy ideas, whether they appear to confirm or contradict what we already know. We only sometimes want to replace old ideas with new ones; more often we want to add complementary perspectives. The ability to bring together diverse viewpoints into a richer, more sophisticated whole is at the center of continually improving your mental models in an increasingly complex world.

Richer Mental Models

“All models are wrong,” noted seminal statistician George Box, “but it is only necessary that they be useful.”36 Some mental models are certainly useful, as has been proven amply true for Charlie Munger. Some people’s models of the world are definitely dysfunctional, as you no doubt will have observed through the course of your life.

What makes our mental models useful or otherwise depends on the context. If you have a simple decision to make, such as whether to take an umbrella with you when you go out, basic mental models are likely to be more useful than elaborate ones. On the other hand, if you are dealing with complex issues such as making strategic decisions in rapidly evolving industries, embarking on a career in the 2020s, or shaping government policies, you will need sophisticated thinking to achieve good outcomes.

Our mental models are necessarily imperfect, and the world is constantly changing. They must evolve; we need to make them richer by including more—and more diverse—elements. The severe challenge we face is to continuously refine our mental models, while retaining the value of the lessons we have learned through a lifetime of experience.

Evolving Our Thinking

Famed economist John Maynard Keynes was highly inclined, almost eager, to alter his opinions, reputedly responding to a critic of his fickleness, “When my information changes, I change my mind. What do you do?”37 Economics is certainly a field in which information from the past is incomplete, new data is constantly flowing in, and carefully constructed models will not necessarily hold in what will inevitably be a different future. Yet even in the “hard” sciences such as physics, experts uncover new information and need to evolve or sometimes completely change their views.

Science historian Thomas Kuhn’s book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, frequently cited as one of the best nonfiction books of all time, describes the nature of how an established orthodoxy goes through a number of phases until a new paradigm becomes current.38 As contrary evidence to the existing view becomes available, defenders and challengers of the traditional framework tussle, going through a stage of crisis until a new widely accepted paradigm emerges.

Obvious examples include the Copernican Revolution, gradually progressing to understanding that the Earth is not the center of the universe, and various Einsteinian conceptual shifts, including the transition from Newtonian physics to general relativity.

We need to apply exactly the same process to our personal models and frames we use to understand the world. We need to acknowledge opposing information, strive to reconcile it with our existing frameworks, and if necessary, evolve our models or sometimes completely throw out old ones to adopt a more useful way of thinking about the world.

Being Right by Being Wrong

“The smartest people are constantly revising their understanding, reconsidering a problem they thought they’d already solved,” according to Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. “They’re open to new points of view, new information, new ideas, contradictions, and challenges to their own way of thinking.”39 He has a low opinion of those who are too set in their thinking. “Anyone who doesn’t change their mind a lot is dramatically underestimating the complexity of the world,” he says.40

What researchers call “actively open-minded thinking” requires not just being open to new information, but deliberately seeking input that could challenge existing ways of thinking. This extremely rewarding capability requires disconnecting your knowledge and beliefs from your identity.

Separate your knowledge from your personal identity to become a better thinker.

If you think of yourself as a highly knowledgeable expert, you may see challenges to your views as personal attacks. As meta-entrepreneur Paul Graham notes, “people can never have a fruitful argument about something that’s part of their identity.”41

If, in contrast, your identity is that you are always eager to learn and update your understanding, you will consider contradictory information as an opportunity to improve your mental models. Respected technology analyst Ben Thompson says, “I am wrong all the time, and I relish the opportunity to say when I’m wrong.” As he observes industry developments, he checks them against his highly developed mental models. He usually finds they fit, but it is most interesting to him when they don’t. He practices his “discipline to avoid confirmation biases” so he doesn’t discount evidence his thinking is incorrect, and can thus consistently expand his worldview. “If you want to be right, admit you’re wrong,” he says.42

Rounding out the five key principles that underlie synthesis is nurturing enabling states of mind. We can learn to evoke the conditions for insight.

States of Mind for Insight

Philo Farnsworth grew up in Idaho. As a youth his parents and teachers could already see he had the makings of genius, but he still had to help out by plowing the potato fields. In 1920, at age 14, as he toiled and surveyed the furrows filled with lines of potatoes, it occurred to him that images could be transmitted at a distance by communicating lines of information, with each potato representing a degree of brightness, and a scan of each line in turn resulting in recreating a live image at a distance. He immediately set to work to bring his epiphany to reality. Eight years later he had built the first functional television.43

There are legion tales of powerful insight achieved, not when striving, but when in more relaxed frames of mind. Archimedes was reputedly in the bath when he solved the problem of assessing whether the gold in the king’s crown had been adulterated, August Kekulé was daydreaming when he intuited the circular molecular structure of benzene, while Nietzsche proclaimed, “It is only ideas gained from walking that have any worth.”

Insight is hard to study, as it so often turns up unannounced. When John Kounios and Mark Beeman first met, they connected through their shared fascination of the potential for neuroimaging to study the evanescent experience of insight. Given their limited resources, they could run only one experiment to prove their intuition. As the results came in, they were delighted to find their instincts proven correct; they had for the first time demonstrated the neurological foundation of the “aha” moment.44

They discovered that specific patterns of brain waves are associated with insight. It is almost a century since we learned that there are distinct sets of frequencies for human neuronal activity, ranging from the delta range of 1–4 cycles per second present during some phases of sleep through to the high gamma range of up to 150 Hertz. Each of the frequencies correlate to different states of mind, with, for example, theta waves (4–8 Hertz) associated with memory formation and deep meditation, alpha waves (8–12 Hertz) present while we are relaxed and calm, and high-band beta (18–20 Hertz) observed during intense active thinking.

Kounios and Beeman found that the moment of insight is associated with a short burst of gamma waves. At the same time, blood flows to the anterior cingulate, located under the prefrontal cortex behind our forehead, which is linked to making distant connections such as understanding humor and metaphors.45 When this part of the brain is active you are more likely to generate creative connections.

What they were surprised to learn is that the flash of insight is directly preceded by a brief alpha state. As they came to understand its function, they called it a “brain blink” during which the brain goes into idle, attenuating visual input to reduce distraction.46 To help gestating thoughts emerge, people often turn inside, closing their eyes or defocusing. Our brains sometimes also spontaneously act to create the mental conditions for inspired connections.

Creating the Conditions for Insight

Getting into the right frame of mind is necessary for powerful synthesis. Your most valuable insights are likely to happen when your brain is in alpha or theta state, which in our busy world is becoming less common and needs to be nurtured. We can act to cultivate our ability to synthesize.

Nolan Bushnell, founder of gaming trailblazer Atari, noted, “Everyone who’s ever taken a shower has an idea.” He goes on to specify that “it’s the person who gets out of the shower, dries off, and does something about it who makes a difference.” Indeed, every successful venture requires novel thinking followed by concerted action.

Showers and baths are widely perceived to be where ideas spring to mind. This happens to be where we are usually in a state of relaxation, with often mid-alpha brain waves, in the pleasure of the moment of the warm water, our thoughts straying whither they will. Some companies sell waterproof notepads and pencils so we can take notes in one of the places where compelling ideas are most likely to arise.

Kounios and Beeman explain why showers are so conducive to insight. “The white noise of the running water is hard to focus on and blocks out other kinds of sounds. The warm water makes it difficult for you to feel the boundary between the interior and exterior of your body, so your sense of touch recedes from awareness. The visual inputs are unchanging and blurry. Perhaps your eyes are even closed to keep the soap out. Taking a shower is an excellent way to cut off the environment, focus your thoughts inwardly, and have an insight.”47

Walks in nature facilitate the “soft fascination” described by the Kaplans in Chapter 4, not only allowing us to regenerate our ability to focus, but also putting us in an appropriate state of mind for synthesis. Many people who exercise more vigorously by running, swimming, or cycling for extended periods often experience a state of mind similar to meditators. Marathon runners in the midst of their 26-mile odyssey tend to greater front theta and global alpha brain waves, which are also strongly associated with insight.48

The brilliant and idiosyncratic Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose book Philosophical Investigations has been cited as the most important philosophy book of the twentieth century, reportedly said that creative thinking depends on the three Bs: bed, bath, and bus.49 At their best, buses and trains have similar characteristics to showers or baths: lulling sounds, defocused attention, and comfort. Being snug in bed offers a similar opportunity for your mind to wander and happen upon unexpected connections.

Hypnagogia is the hinterland between wakefulness and sleep, when fragments of the dreaming state start to enter your consciousness. Many people in this state startle back awake when an idea comes to mind, sometimes to make a note before the thought is lost. Surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, not surprisingly given his dreamlike art, was heavily inspired by the “repose which walks in equilibrium on the taut and invisible wire which separates sleeping from waking.” Technology futurist Cathy Hackl reports that insights often come unbidden when she is going to sleep. “All of a sudden, boom, it’s there and connection is made; I totally understand, and I see something I didn’t see before,” she reports.50

Inventor Thomas Edison worked late and long, but also napped most days, waiting for the next brilliant idea to strike him. In a technique also used by Dalí, he rested and held a steel ball in his hand poised above a metal plate. When the ball fell out of his hand he woke and immediately wrote down the ideas that had come to mind.51 President John F. Kennedy combined some of these techniques, often having an afternoon nap as well as two hot baths each day.

Seeding and Incubating

When a chick pecks its way out of its shell, it does not appear out of nowhere. It has sat for an extended period in conducive conditions, nurtured to the point where it is ready to come forth into the world. Creative synthesis often comes to us in a moment, however, usually after extended gestation in our unconscious minds. When we struggle with a conceptual problem for a long time, it is commonplace for the answer to spring to mind when we are doing something completely different. Our brain has been working for us while we pay attention to other things, engaging in “opportunistic assimilation” of perspectives and ideas relevant to the problem it is trying to solve.52

Knowing that synthesis requires incubation allows us to carefully plant the seeds of ideas and tend to them so they are most likely to bear beautiful fruit. When we are struggling with a problem, if we cannot solve it on the spot we should aim to surface as many outlooks on the challenge as possible, providing our unconscious mind with better raw materials for incubation, then do something else.

Nikola Tesla was one of the many inventors who implicitly understood this. “I may go on for months or years with the idea in the back of my head,” he said. “Whenever I feel like it, I roam around in my imagination and think about the problem without any deliberate concentration. This is a period of incubation.”53

In turn, plant seeds through focused thinking and cultivate them through expansive states of mind.

These two states feed on each other; they only have true value in conjunction. A facility for evoking and switching between different frames of mind is a powerful enabler of synthesis. Kounios and Beeman propose that “alternating between the inner and outer worlds is the best way to enhance your creativity.”54

The ultimate value of our ability to synthesize information and refine our mental models is in our actions. We need to apply the full ambit of the insight we have developed to making better decisions.

Informed Decisions in an Uncertain World

John Boyd signed up for the Army Air Corps at age 17 in the final year of World War II, training as a pilot and flying in Korea as an F-86 pilot. After his tour of duty, he was inducted into the Fighter Weapon School, took top marks, and was asked to become an instructor at the academy.

His self-confidence was legendary. He threw out a standing bet that he could trounce any comer in simulated air-to-air combat within 40 seconds, offering $40 to anyone who could beat him. Many took up the challenge, but Boyd never had to take out his wallet.55 His superlative ability was based not on his reflexes, but on the quality of his mental models.

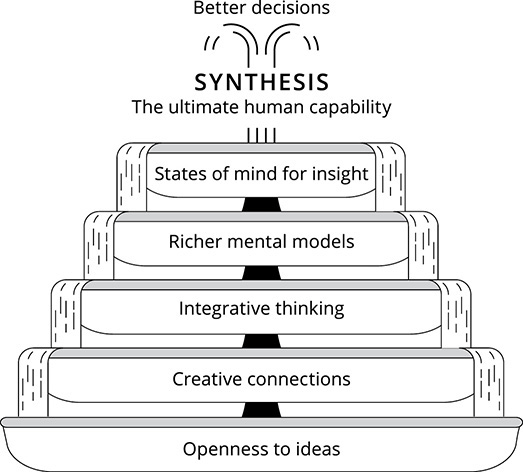

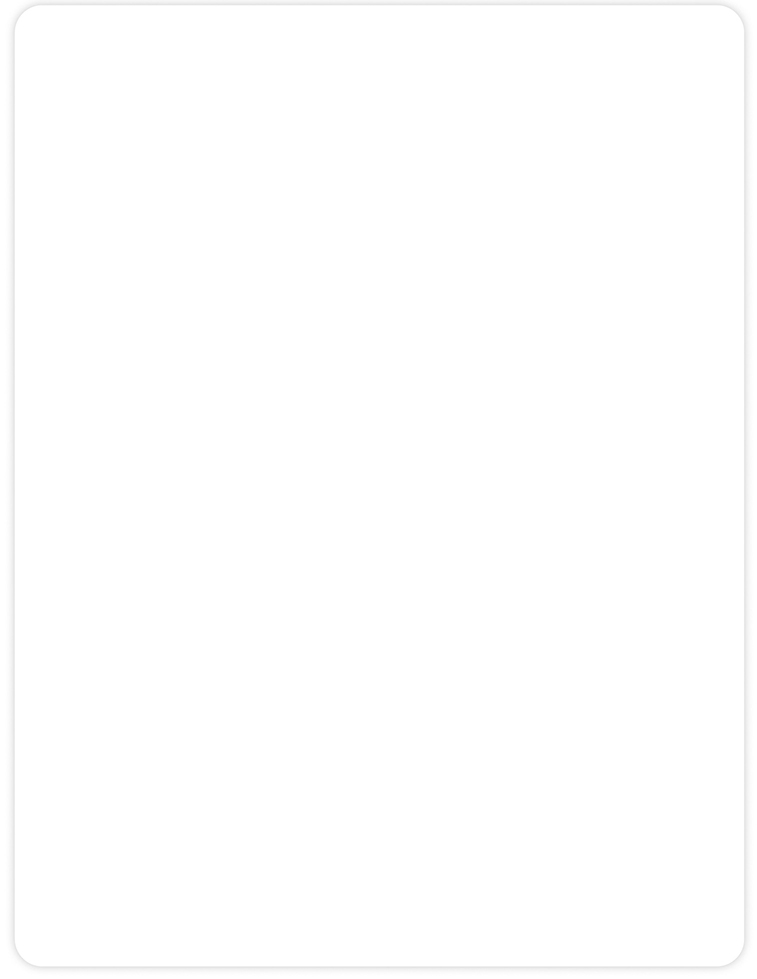

Throughout his life Boyd sought to build frameworks for high-pressure decision-making that could be taught and studied. Among these he proposed the OODA loop, connecting the four phases of Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act into a virtuous cycle of learning. The idea was developed to help fighter pilots defeat their opponents, but decades later the OODA loop is also applied extensively in business and engineering. Notably it was a central inspiration for the Lean Startup loop that sits at the center of the strategy of virtually every startup in Silicon Valley and beyond.56 Boyd had highlighted that making effective decisions involves continual learning as well as action.

Decision-making requires synthesizing the information you have, but always entails uncertainty. For example, if you are considering investing in an early-stage startup, you will undoubtedly be shown a snappily designed presentation including jaw-dropping revenue forecasts. If you ask the right questions, hopefully the founders will be able to provide the specific assumptions on which their targets are based. Whatever you are told, the degree of uncertainty in the company’s prospects is huge, and you will never have enough information to be confident in the fate of your investment. But if you use that as a reason to walk away or wait until there is more evidence, you may be missing out on a runaway success. How should you make a decision? Let us examine some frames on decision-making that may be helpful.

Iterative Decisions

Herbert Simon coined the neologism “satisfice” to describe decisions that sufficed to satisfy a threshold of acceptability. Historically, economists and psychologists have liked to assume humans are utterly rational and have perfect information. Fortunately, most now acknowledge that humans are rarely fully logical, and we seldom have all the information we want.

In fact, more information is not necessarily better. Former secretary of state Colin Powell declared, “I can make a decision with 30 percent of the information. Anything more than 80 percent is too much.”

Gathering and assessing information has a real cost, not least in time and cognitive processing. An essential choice for all decision makers is whether they should make a decision with the information they already have available, or they need more input. In an uncertain environment the best way to proceed—if at all possible—is to make smaller decisions that will yield information to improve subsequent and potentially larger decisions. The faster the pace of change, the greater the potential cost of delaying decisions and the higher the premium on swift action.

Formulate decisions that will make you better informed for your next decision.

This is at the core of the lesson John Boyd derived from his experience training the world’s best fighter pilots. His OODA loop, depicted in Figure 5.3, describes the process of learning from your decisions and actions. To improve performance, decisions must result in outcomes you can observe and learn from, designed to surface whatever information will be most valuable for your next decision. As much as possible make iterative decisions, building on lessons learned from previous ones.

FIGURE 5.3 OODA Loop for Iterative Decision-Making

Decisions as Bets

As you learned in Chapter 3, the Bayesian approach of thinking in probabilities is immensely valuable in filtering information. It allows us to move past considering new information as either confirming or invalidating our beliefs. We can instead assess how it might adjust our mental models and assessments.

This mindset is just as relevant in decision-making. By definition all decisions deal with uncertainty. The only appropriate response is to think explicitly in terms of probabilities.

Shortly before completing her PhD dissertation in cognitive psychology, Annie Duke fell ill, took a leave of absence, married, and moved to rural Montana. Her funds were running out, so she learned to play poker to pay the bills, starting out in the basement of a local bar. She never returned to her formal studies, but thought of poker as a “new kind of lab for studying how people learn and make decisions.” In her subsequent career as a professional poker player she ended up winning over $4 million and a range of major tournaments, including the World Series of Poker Tournament of Champions, going on to advise senior executives on how to improve their decision-making.57

Poker provides a strong analogy for many real-world decisions. Holding your cards and deciding your play, you face significant risk, partial information, and other participants with unpredictable and sometimes deceptive behaviors. Whenever you place a bet, take a card, or fold, it should be based on your assessment of the odds.

“Getting comfortable with ‘I’m not sure’ is a vital step to being a better decision maker,” says Duke. “We have to make peace with not knowing.”58 This is hard, but in an increasingly unpredictable world, we must acknowledge the reality of uncertainty.

More than ever, leaders and decision makers need to not just accept but embrace ambiguity.

The 2020s have taught us, if we didn’t already know, that striving to make the world knowable is a fool’s errand. Conceding uncertainty frees us to make assessments based on limited information, examining all perspectives on our possible actions. Starting with a careful evaluation of probabilities lets us place our stakes more wisely.

“Thinking in bets triggers a more open-minded exploration of alternative hypotheses, of reasons supporting conclusions opposite to the routine of self-serving bias,” believes Duke. “We are more likely to explore the opposite side of an argument more often and more seriously—and that will move us closer to the truth of the matter.”59

Consider the Opposite

Professor Rick Larrick of Duke University specializes in the subtle and challenging art of “debiasing,” helping people move beyond their biases. He draws on decades of extensive research that confirms the most promising approach is the simple yet powerful approach of “consider the opposite,” asking yourself, “What are some reasons that my initial judgment might be wrong?”60

This apparently modest exercise has been shown to reduce a variety of biases, including overconfidence. The value of this is underlined by Daniel Kahneman’s statement that overconfidence is the “most damaging” of the multitude of biases that afflict us.

In the nineteenth century the Prussian army brought together a divided Germany, in the process defeating France, Austria, and Denmark. The Prussians’ success was attributed in part to their innovative use of war gaming to temper their strategies. On their boards the Prussian army was represented by blue blocks to indicate the famous Prussian blue uniforms worn by their soldiers. The teams playing the enemy used red blocks to indicate their regiments, giving rise to the phase “red teams” to describe groups who are tasked with finding flaws and problems with strategies. The longstanding use of red team exercises by the US military has increased significantly since the September 11 attacks.61

Similar approaches are now common in large investment management firms. The cost of making a bad decision can be enormous, so you need to test decisions against the unexpected. “It’s the responsibility of everybody else in the room to stress test the thinking,” says Marc Andreessen of the decision-making process of leading venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. “If necessary, we’ll create a red team. We’ll formally create the countervailing force and designate some set of people to counterargue the other side.”62

Hedge fund Bridgewater, led by Ray Dalio, is one of the most successful investors in the world, managing $160 billion and over 28 years averaging double the returns of the S&P 500. Forceful questioning by employees of suggested investments or others’ opinions is not just tolerated, it is expected, to ensure decisions are fully robust. Adam Grant, who has studied the firm’s processes, says of Bridgewater, “You get rated on whether you are challenging your boss. . . . They basically evaluate you on whether you’re fighting for right, even when other people disagree.”63 At Netflix everyone is expected to actively seek different opinions before major decisions; CEO Reed Hastings calls this “farming for dissent.”64

Let’s look at how you could apply these lessons to whether to invest in the early-stage startup introduced earlier. First, you should acknowledge your investment is a bet that you may win or lose, and your task is simply to use all information available to assess the likelihood of success. You might ask someone who knows the industry to help identify the reasons the startup might fail. The greatest value from that will be seeing if the founders have already considered these issues, demonstrating the openness of their thinking, and have decent responses. Or you might make a smaller initial investment so that you can access company reporting and have better information to decide whether to invest more in subsequent rounds.

In an increasingly complex and uncertain world, the vital skills of synthesis are fundamental not just to your life, career, and ventures, but far beyond. We need to get better at synthesis, individually and collectively, to create a better future.

Synthesis and the Future of Humanity

In my role as futurist, I often say that as soon as you look far enough into the future of any domain, be it work, retail, homes, healthcare, media, cities, the environment, or anything else, you are essentially considering the future of humanity. Everything in our world is richly intertwined; any subject you can consider is inherently related to everything else.

Synthesis is a profoundly creative act. By bringing together diverse elements in a fresh way, you forge a new reality. And in that generative act you cannot help but bring to bear the full scope of who you are and your perception of the world.

Synthesis is precisely about perceiving the entirety, comprehensively taking into account everything that is relevant. This includes the role of people and the broader context of our planet in which we are set. One reason humans will always transcend machines in their ability to synthesize is that they can empathize and comprehend the implications for humans in ways algorithms never can. Seeing the whole is essential to understand what is possible and the paths that lead there.

The capacity for synthesis sits at the heart of our ability to create a better future for ourselves and humanity.

More of us improving our capabilities at synthesis will maximize the chances that our collective future will be better rather than worse. As you further develop your power of synthesis, you will inevitably be contributing to a better future for us all.

Integrating the Power of Synthesis

Synthesis is the master key that unlocks the potential of the four other powers, bringing them together to create understanding, insight, and the ability to act effectively in an incredibly complex world. More than ever, it will be the central capability in a rapidly accelerating future of work.

Each of the tiers in the wellspring of synthesis represents skills that we can develop. The future belongs to those open to continually improving their minds and thinking. You can make the choice to change yourself to become better adapted to the state of the twenty-first century. The accompanying benefits include better mental health, happiness, and longevity.

By enhancing your capacity for synthesis, you are now better able to integrate the five powers into a whole that suits you perfectly. This will amplify your ability to prosper in our extraordinary rapidly unfolding world, truly thriving on overload.

EXERCISES

Contrarian Thinking

Identify an issue related to your work where you have a strong opinion but you know some people disagree. Clearly articulate your opinion, then research and develop a strong argument for the contrary case. To make it more challenging, do it for a specific social or political issue.

Active Open-Minded Thinking

What will you do to enhance your capability and propensity for openness to new ideas and different thinking? What thinking habits can you adopt that will help? Are there any activities that might positively shift your openness to experience?

Insight Mode

What activities or behaviors help you get into insight mode? How can you plan these into your day?

Incubating Ideas

Choose a significant decision or conceptual challenge and aim to ready it for incubation. Consider it from as many angles as possible without necessarily looking for a solution. Later, come back to it, and find ways to bring yourself to insight mode. Make this a consistent practice and discover what approaches work best for you.