Relationships and collaboration

The opening questions

- What issues have you recognised within inter-team or inter-department collaboration?

- What relationships within teams or within departments are positive?

- What collaboration or relationship issues at work affect you personally?

Promoting mindful relationships

Can we all get along? Can we all get along?

Rodney King, 1992

While Rodney King was speaking on a socio-global issue, the macro world is reflected in the micro. Teams that are unable to ‘get along’ often find it difficult to pull together to achieve. While teams do not need to be ‘best friends’, a respect and acknowledgment of each other’s value is essential for good performance. Mindfulness promotes acceptance of the self and other, while respecting that each view is valuable – and while we can ourselves learn to collaborate with it, we do not have the right to change it within one another (Excellence Assured, 2017).

Just ask for it!

The MBSR course from Mindfulness Works (2017) suggests that one of the most important things in enhancing collaboration is first to make it clear that collaboration is the aim. When bringing a team together:

- identify collaboration as the intention of the group

- make it clear that each contribution is valuable, especially as it might be from a perspective different from our own.

However, in remote teams this may not be easy to do consistently.

The problem with collaboration

In 2002 Patrick Lencioni immortalised the five dysfunctions within a team ranging from the absence of trust to inattention of results. When a team was not functioning efficiently, performance would suffer as much as the distorted emotions within the situation.

At the very basis of a team not wanting to collaborate was the absence of trust.

As with not wanting to share their ideas, discussed in the last chapter, it is not uncommon for teams to mistrust each other. This may be due to past experience, to a fear that their personal standards will not be met or even that their work may be undermined or sabotaged. If they already lack confidence in themselves or their ability to be recognised by their leaders, so grows their desire to go it alone – or act with limited input from others. This way they maintain control of their own output and can reap the rewards.

However, as also explored in the last chapter, collaboration brings many benefits – the ability to identify and rectify mistakes sooner, respect for the roles that others play and the skills that they have, and a greater outcome than if one were working alone.

Nonetheless, being forced to collaborate can still result in issues higher up the pyramid, namely a fear of conflict and a lack of commitment. Both can result in lip service being paid to teamwork rather than actual efforts capable of making a difference.

Fear of conflict may be in regard to wishing to maintain a comfortable existence. Even the idea of conflict can cause the stress response to arise in some (if this happens, please engage in the deep breathing exercises in Chapter 1), as such it is sometimes easier to offer the show of being part of the team while choosing not to commit. While this may not have a hugely detrimental effect, a team which is unable to utilise positive conflict to highlight and solve problems, or commit to a joint outcome which has the potential benefit of a team of good brains rather than one or two, also misses out on the benefits.

Lack of accountability and inattention to results are, therefore, what is left for a team which collaboration eludes – a result which will not reach potential and cannot (or will not) be learned from.

So, what is the mindful manager to do?

Encourage greater understanding of the importance of the team through the following:

The scrum

Developed by Takeuchi and Nonaka (1986), the ‘scrum’ derived from the behaviour of rugby players going in for the ball and getting it back into play. It has been taken under the wing of project management techniques and suggests the implementation of a system where teams give consistent feedback on their work. A daily ‘scrum’ would:

- reflect on what was done since the last scrum

- identify the obstacles or any backlogs

- set the objectives for the day.

This is not in replacement of a meeting, but it is a fast and effective way to touch base with each area of a project (no matter how remote, as Skype or video conferencing could be used), as well as allowing each team to take responsibility for their role and bringing that information to the scrum.

A scrum, covering those three points, with adequate preparation from each area, should take no longer than a few minutes.

As with many mindfulness techniques, this is a practical means of visualising the outcome as a whole, taking into account the different elements. Teams are able to appreciate their part in the overall outcome and value each other’s contribution. Furthermore, it makes it easier for teams to be responsive to issues and there is a culture of giving feedback swiftly so that problems can be dealt with at once – thus removing the fear of offering up a problem into a ‘blame culture’. (It even offers a good opportunity for praise if things are going smoothly.)

Kanban

Kanban was developed by Toyota engineer Taiichi Ohno (1988) as a means of enabling all facets of a large-scale production to be aware of what was going on at all times. It has since been developed into computer software, which can be installed within the organisation.

While Kanban was developed in response to manufacturers wanting to be more responsive to customer demand, its technique can be applied to any wide-scale project.

- Outline all the processes that the product or project needs to go through, in order – taking into account every department working on the project.

- List the tasks.

- State the deadline(s).

- Instruct each team to indicate on the system (which may be a board in a communal work area or computerised software) when they are completed by writing the date of completion and ticking off the column before.

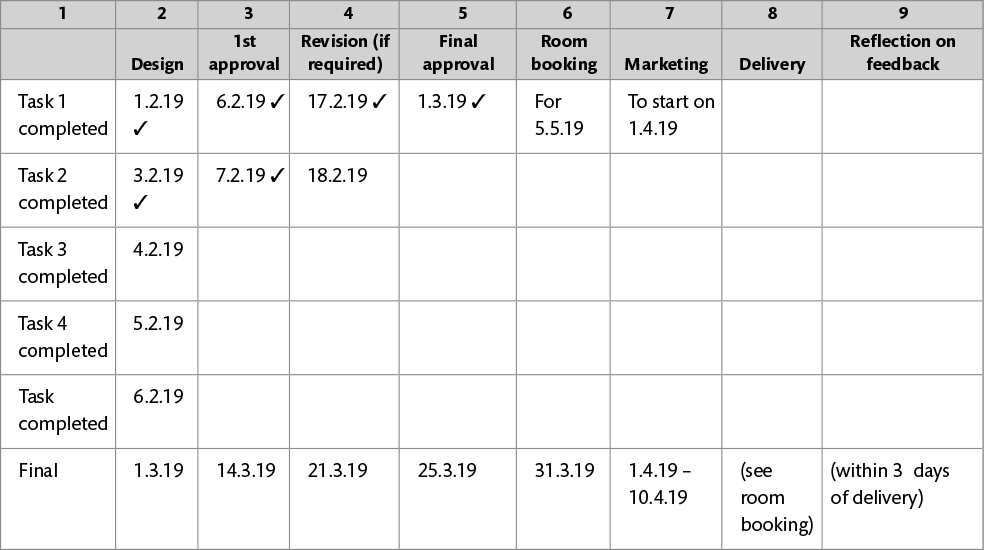

For example, it might look something like this:

By each team or person stating when their work is ready (with awareness of the deadlines), it can be pulled through by the next team. This is possible for any number of projects as long as they are all listed. Using the example above, if there are five training programmes, all five can be listed either with respective deadlines – or within one overall deadline.

What makes Kanban even more efficient is putting in ‘rules’ which are relevant to the process. For Toyota, if a product was found to be defective at any stage, it would be removed immediately. Using the example above, if there is a rule that (for quality purposes) only two training programmes can be evaluated at one time (e.g. there can only be a maximum of two items (or dates in this case) in the column stating ‘first approval’ – if there looks like there will be a backlog (as in the example where all five of the programmes have been written, but not pulled through for approval), this is something that is flagged up and someone else can be assigned temporarily to help unblock the jam. Kanban is, clearly, most efficient when everyone is aware of what needs to be done – and if more than one group or one person is competent at each task.

This also enables the leader to see at a glance where patterns of issues (or performance excellence) arise. Further, because this process requires a multi-skilled team, there are always areas of development you can offer each person in each area.

Kabat Zinn (the ‘founder’ of mindfulness in business) has always asserted that one of the goals is to encourage others to be more mindful so that we build a more altruistic society. Bunting (2016) breaks this down further in his suggestion that mindfulness allows you to ‘see worthiness in others’ and to ‘be compassionate’ – in the workplace this allows us to see conflict less as a threat with others as obstacles to your success, but to look for root causes of the external ‘problem’ behaviours.

Both the systems proposed enable this visualisation of worthiness in others as well as embedding reflection and revision as a matter of course – a behaviour to be engaged in without fear of blame or repercussion.

This is not to say that the leader should not take steps to deal with consistently poor performance or areas where performance is hindered by tools or other practical matters, but, through keeping an overview of the whole picture, it enables these areas to be identified faster and any issues to be investigated and dealt with in their early stages.

Again, you will notice that meditation has not yet been proposed, and these techniques are presented as practical ways of remaining aware of, and being engaged with, the present as it happens. But what better way to enable mindfulness?

A slightly faster way to introduce such awareness comes from an exercise derived from Kanban and the scrum, known as the ‘Collaboration Cycle’ (Gordon et al., 2018):

EXERCISE 4.1

At the start of a collaborative project, show teams the outcome and ask them to explain their role in production, for example:

In the production of a pen there may be different teams producing the cap, the shaft, the ink, the box – each with different needs and time scales. By each team explaining their role and their exacting needs, appreciation of each element and the importance of following each team’s specifications and timescales is emphasised.

It is not uncommon for theatrical teams to have a ‘production’ meeting prior to the actors starting rehearsals to discuss timescales and needs and, sometimes, it is also essential for the actors to meet with the stage management and technical side so that both have an understanding of requirements. (It is not unheard of for actors to sometimes think themselves the centre of a project, when they may need to appreciate that without light, a stage, sound or a set, there is often no project!)

The act of making each person aware of the others’ contributions goes a long way to building an understanding of their demands.

Breaking down barriers to collaboration

EXERCISE 4.2

Even on a small scale, if you are introducing a new system into your team, ask the whole team to work with it and give you feedback rather than just those who would naturally access it daily. You may find that teething troubles are more quickly identified and your teams begin to have a clearer understanding of each other’s contribution.

Then reflect on how well this process worked for you.

EXERCISE 4.3

Next time you set a project for your team, ask them to generate the solution and work on the implementation in pairs.

Reflect on the outcomes.

The act of the swarm or allocated pairs removes the psychological barriers to collaboration but makes collaboration a natural part of the working day.

This may also have the bonus benefits of teams being able to better appreciate each other and adapt to each other’s needs, improving compassion and support within the organisation overall.

Again, another mindful outcome.

| 4. | Embrace self-selection |

| Try this exercise. |

EXERCISE 4.4

You are writing a job description for this new organisational approach to collaborative working. However, you are not necessarily convinced that swarms or teams will work. One of the points of the job description will be that all staff work in pairs. Another is that all staff are expected to learn new initiatives.

How would you word your job description?

Mindful relationships

For the leader who is missing the use of a more meditative exercise, mindful meditation has also been shown – in its ability to calm the mind to bring benefits to relationships. The power of deep breathing to reduce the stress response lowers the production of cortisol, which in turn lowers the likelihood of impulsivity – beneficial for the prevention of saying or doing something which may damage a relationship unnecessarily.

While the evidence for neurological changes in the mind is limited, research has shown regular mindful meditation to:

- increase connectivity between the amygdala (the alarm centre) and prefrontal cortex (executive centre), which helps prevent you getting stuck in negative cycles or ‘stewing’ and move towards taking positive action

- strengthen the anterior cingulate cortex (associated with self-perception and cognitive flexibility), which again helps motivate you to make changes rather than remain within a cycle of insecurity or mistrust

- create change in the insula (associated with emotional awareness and empathy), making you more able to offer an open, accepting attitude towards others.

(Greenberg, 2016)

IN SUMMARY

- Remind your teams that the main objective is achievement through collaboration. Plainly, and simply, with the collective goal as the focus, personal squabbles can be left at the door.

- Use the Kanban Technique or the Collaboration Cycle to ensure that all facets of the team appreciate and understand the workload and pressures that they, respectively, face.

- Utilise the scrum, Kanban or goal-related briefings to keep abreast of any issues.

- Encourage teams to collaborate, reflect, give feedback and respond throughout the working process as a matter of course. Organisation into swarms, squads or pairs can help.

- Potential team members who ‘self-select’ themselves out are not your biggest concern – be mindful of including those who mindlessly agree to everything.

- Encouraging or providing the opportunity for mindful meditation with a focus on compassion can help teams become more patient and understanding (you can use the accompanying downloadable meditation).

- Shout about your organisation’s culture of mindfulness.

Should you wish to practise a meditation for compassion, please download. Go to https://www.draudreyt.com/meditations (Password: leaderretreat).

CHAPTER 4 TOOLKIT

- The most effective leader is the person who can harness the mind of the collective to achieve more than could be done alone.

- Mindfulness can assist in highlighting the common goal, as well as generating a greater sense of understanding and compassion within collaborations.

Key points to remember

- Always state explicitly to teams when collaboration is expected and try to find a clear means of demonstrating each team’s contribution

- Sometimes find an opportunity for teams to meet, even if it is a short conference call to update.

- Try to see critical feedback and reflection as progressive and instil this within your teams through practice, i.e. requesting that everyone learns a new initiative and feeds back.

Take action

| 1. | Practise giving and receiving feedback (and teach this to your teams) | |

| When giving: | ||

| • | Identify the feedback criteria prior to the event. | |

| • | Try to stick to what was observable and give evidence. It is not enough to say, ‘I didn’t think you did that efficiently,’ without saying why or giving an example of what it was that made you think that. | |

| • | Identify the elements that were competent (and better than competent!) – again, give examples of what was successful in performance. | |

| • | Be honest – it’s not about being ‘funny’ or getting someone to like you or asserting authority. | |

| When receiving: | ||

| • | Retain open body language. | |

| • | Acknowledge what you perceive as fair criticism. Do not forget you may ask for clarification and an example if it was not offered, e.g. ‘You said I sounded abrupt – was this the case all the way through the conversation?’ | |

| • | Try not to argue – wait until they have finished before choosing to respond. | |

| • | If nothing positive has been offered, ask what you did well (some people feel saying nothing means it was good). | |

| • | Recap the feedback in full – to check you have understood it. | |

| • | Thank the person, but also say which comments you have chosen not to accept (if applicable) and explain why. (This may open a helpful dialogue.) | |

| • | Ask for advice on improvement if this has not been given. | |

What worked for me

| Date | Action |

| | |

Please use a separate piece of paper if necessary.

Meditation techniques

Meditation for compassion

This is a short meditation for compassion.

To begin, take deep centring breaths – breathing in through your nose and out through your mouth. With each breath you feel calm and relaxed.

In through your nose and out through your mouth.

If any thoughts cross your mind, acknowledge them and let them pass.

If any sounds cross into your focus, acknowledge them and let them pass.

Breathe in through your nose and out through your mouth.

Picture someone you feel affection for. It can be anyone at all. Get a clear image of them in your mind and make that picture bright and vibrant.

Breathe deeply and calmly.

As you picture them, say these phrases either in your mind or out loud:

May you be happy

May you be strong

May you be free from suffering

May you be happy

May you be strong

May you be free from suffering

Once more:

May you be happy

May you be strong

May you be free from suffering

Now picture someone whom you would like to forgive.

Even if you are not ready to forgive them completely, wishing them well means they no longer have a hold over you.

See that person in your mind and repeat:

May you be happy

May you be strong

May you be free from suffering

Again:

May you be happy

May you be strong

May you be free from suffering

Finally, see yourself as if looking in a mirror and repeat those same phrases:

May I be happy

May I be strong

May I be free from suffering

Again:

May I be happy

May I be strong

May I be free from suffering

Continue to breathe deeply and, when you are ready, become more aware of the room and open your eyes ready to get on with your day.