Why Geek Leadership Is Different

It has been said that in any group of people, a small fraction will be leaders, a larger fraction will be followers, and a substantial portion just will not want to get involved. A leader is part artist, and in IT, this art requires blending technology skills, process skills, and, most importantly, people skills to produce products and services that deliver value to customers. You can administer networks, servers, and databases; you can program computers; you can design and implement processes; and you can manage projects—but people must be led. This means motivating them to achieve their highest performance by creating a vision, building teams, providing direction, and resolving conflict. This means building relationships—having frequent dialogues and making connections with team members and other project stakeholders. You can judge the success of leaders by the success of their followers and by their ability to perform in a manner that achieves their vision.

But people are the wildcards in the game of IT projects. They are unpredictable and sometimes chaotic. They are influenced by their instincts and emotions. They see and hear things differently based on their individual perceptions, filters, and experiences. They have different backgrounds and preferences. They don’t always understand each other or even like each other. But mostly, in my experience and in accordance with McGregor’s Theory Y (McGregor, 1960), IT people want to do a good job—they want to learn, achieve, and do well at work, and they look for their leaders to provide the support and coaching they need to perform well. Management tools and techniques such as quality control and risk management are important, but projects will not succeed unless people receive the leadership they need.

In 2015, for the first time, the US Government Accountability Office added “Improving the Management of IT Acquisitions and Operations” to its annual High Risk Report, stating, “Although the executive branch has undertaken numerous initiatives to better manage the more than $80 billion that is annually invested in information technology (IT), federal IT investments too frequently fail or incur cost overruns and schedule slippages while contributing little to mission-related outcomes” (GAO, 2015). The Standish Group International reports that in 2012, 61% of IT projects worldwide were challenged or failed altogether.

As a program manager, I once supervised a team leader, let’s call him John, who was responsible for Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) Configuration Management processes for a large IT support operation. We needed to mature our processes, so it was important that John establish relationships with the other leaders within the enterprise in order to integrate processes across the organization. We needed him to lead the integration effort, and we provided him with clear objectives for his positon. After several months, we did not see the progress we expected. Instead, John focused his efforts on a network engineering project that was only tangentially related to his position. This effort did not require him to talk to anyone. “I just want a job where I can put my head under a hood all day, do my work, and then go home,” he told me. Realizing that he was not a good fit for the role, and also that he was not willing to make the effort to adapt his style to fit the position, he soon left. Fortunately, we were able to fill the position with someone with strong leadership skills soon after his departure.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, many front-line leaders in IT have never obtained leadership training, and John was one of them. To increase the rate of success of IT programs and projects, we need leadership from the bottom of organizations up. IT personnel such as programmers, database administrators, and network engineers are accustomed to being evaluated on the quality of their individual contributions. Leadership is different—it requires different skills because the leader is responsible for the performance of his or her group and for managing relationships with stakeholders. IT geek leadership is different because IT geek leaders are not natural leaders. As we will explore in this chapter, most IT geek leaders are introverts and are more comfortable being “under the hood all day” and not talking to people. Yet, research indicates that 90% of project management is communications. The IT leader who does not know how to communicate with people will fail. This book can help IT geek leaders understand the art of leadership, enabling them to adapt to the requirements of IT leadership and increase the rate of IT project success.

Leadership is an abstract term that invokes philosophical perceptions concerning the impact of one person’s influence on others. Many have described and defined leadership in various ways.

Businessdictionary.com defines leadership as:

1. The individuals who are the leaders in an organization, regarded collectively.

2. The activity of leading a group of people or an organization or the ability to do this.

Leadership involves establishing a clear vision; sharing that vision with others so that they will follow willingly; providing the information, knowledge and methods to realize that vision; and coordinating and balancing the conflicting interests of all members and stakeholders (Leadership, n.d.).

Table 2-1 lists a variety of leadership attributes from different reputable sources.

“Are leaders born or made?” This question has served as a source of intellectual nourishment for ages. There are two major perspectives on leadership: the trait perspective and the process perspective.

Table 2-1 Leadership Attributes

Leaders are: | ||

Team builders | Bold | Intelligent |

Motivators | Risk takers | Articulate |

Communicators | Planners | Perceptive |

Influencers | Inspiring | Self-confident |

Decision makers | Courageous | Self-assured |

Politically aware | Listeners | Persistent |

Culturally aware | Decisive | Determined |

Negotiators | Visionaries | Trustworthy |

Trust builders | Passionate | Dependable |

Conflict managers | Motivators | Friendly |

Coachesa | Organizers Critical thinkersb | Outgoingc |

a Data derived from Project Management Institute (2013). Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, (PMBOK® Guide), 5th ed. Newton Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

b Data derived from Toast masters International (2005). A Practical Guide to Becoming a Better Leader—Competent Leadership Guide. Mission Viejo, CA: Toastmasters International.

c Data derived from Northouse (2007). Leadership: Theory and Practice, 4th ed. London, UK: Sage.

According to the trait perspective, leaders have special inborn, innate characteristics that set them apart from others. These factors include physical traits such as height, personality features such as extraversion, and abilities such as fluency of speech (Northouse, 2007).

The process viewpoint sees leadership as a set of behaviors. From this perspective, leadership can be learned (Northouse, 2007). Those seeking to become leaders can improve how they interact with followers, enhancing their leadership effectiveness.

There were several studies of the trait approach to leadership in the 20th century. These studies have resulted in a list of traits that are desirable to those of us who seek to be perceived as leaders: intelligence, self-confidence, determination, integrity, and sociability.

• Intelligence. Researchers have found that leaders tend to be more intelligent than non-leaders. However, if a leader’s intellectual ability far exceeds his or her followers, there could be a counterproductive impact on leadership.

• Self-confidence. Self-confidence, including self-esteem, self-assurance, and the belief that one can make a difference, invokes positive feelings within leaders concerning the actions they take to influence their followers.

• Determination. Effective leaders are perceived to be determined, to exercise initiative, to be persistent, and to drive toward results. They assert themselves proactively to overcome obstacles.

• Integrity. Lastly, leaders exhibit integrity, demonstrating honesty and trustworthiness. They take responsibility and hold themselves accountable, inspiring confidence in others because they are trusted to keep their word (Northouse, 2007).

There are core leadership skills that researchers have found to be advantageous to those seeking promotion into leadership positions. These skills can be learned, enabling the prospective leader to become more effective.

• Strategy, including vision, acumen, planning, and the courage to lead:

○ Vision. Leaders have the ability to envision a new reality and inspire followers to take action to realize it.

○ Acumen. Leaders see the big picture and understand how it impacts their present situation.

○ Planning. Leaders perceive and anticipate future events and design goals and activities to prepare for those events.

○ Courage to Lead. Leaders take calculated risks—they stand firm in the face of adversity.

• Action, including decision making, communication, and mobilizing others:

○ Decision Making. Leaders consider and weigh alternatives and then determine the course of action.

○ Communication. Leaders facilitate free-flowing thoughts and information sharing.

○ Mobilizing Others. Leaders convince others to take actions toward the envisioned future state.

• Results, including risk taking, result-focused actions, and agility:

○ Risk Taking. Leaders venture into uncharted territories in order to achieve their objectives.

○ Results Focus. Leaders avoid distractions and help their subordinates avoid them as well, staying on course to achieve the desired goals.

○ Agility. Leaders adapt to changing situations and address uncertainty creatively (Bradberry and Greaves, 2012).

Erika Andersen, author of Leading So People Will Follow (Andersen, 2012a), provides a rational and balanced viewpoint that attempts to reconcile the contradiction between born and made leadership perspectives. At Forbes.com, she posted, “What I’ve learned by observing thousands of people in business over the past 30 years, though, is that—like most things—leadership capability falls along a bell curve. Some people are, indeed, born leaders. These folks at the top of the leadership bell curve start out very good, and tend to get even better as they go along. Then there are the folks at the bottom of the curve: that bottom 10–15% of people who, no matter how hard they try, simply aren’t ever going to be very good leaders. They just don’t have the innate wiring.

“Then there’s the big middle of the curve, where the vast majority of us live. And that’s where the real potential for ‘made’ leaders lies. It’s what most of my interviewers assume isn’t true—when, in fact, it is: most folks who start out with a modicum of innate leadership capability can actually become very good, even great leaders” (Andersen, 2012b).

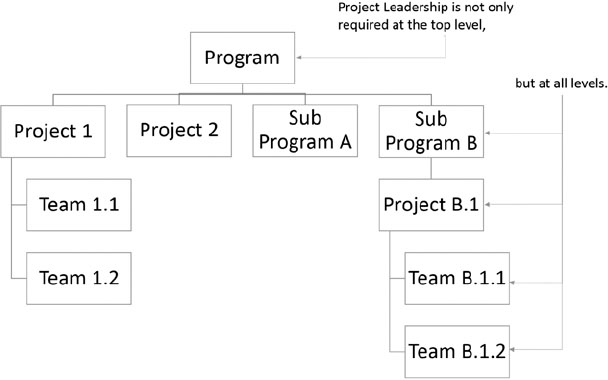

Many IT solutions are delivered in programs and projects. Program managers provide high-level leadership for programs. According to the Project Management Institute (PMI®), a program is “a group of related projects, subprograms, and program activities that are managed in a coordinated way to deliver benefits not available from managing them individually” (Program Management Institute, 2013a). An IT program to develop a point of sale system for a restaurant chain, for example, may comprise software development, hardware configuration, and network configuration projects.

Also according to the PMI®, program managers are responsible for defining the program vision, mission, goals, and objectives. They define the program components (projects and subprograms) to develop deliverables that, when integrated, achieve the vision. Program managers apply leadership throughout the program life cycle, setting goals for the project team and expectations for stakeholders (PMI®, 2013b).

Not only must program managers apply leadership skills to align the program with organizational objectives, they must also develop the leadership skills of the project managers on their team.

PMI® advises that project managers require leadership skills to be personally effective (PMI®, 2013a). The project leader leads project activities such as initiating, planning, executing, monitoring, controlling, and closing out projects. The program manager relies on the project leader to influence the team’s behavior in a manner that leads to successful development of deliverables, which enable the program to deliver the desired benefits. The program manager needs the project leader to communicate effectively, manage conflict, motivate team members, and facilitate problem resolution.

Because IT projects are complex and subject to frequent changes, IT project leaders need a flexible leadership style and excellent communication skills to influence the reduction of complexity and to effectively control change.

IT project leaders are responsible for organizing and leading team-building activities for their project teams. The complexities of IT projects require team members to be comfortable working with each other. They need to trust each other to perform their assigned tasks well. This trust goes beyond appreciation of technical skill sets and application of sound processes. Relationships are required to develop trust. People more easily communicate and work well with people they like. If people like each other, they are more likely to have synergy, to produce far more together than they would on their own. The project leader is responsible for creating environments that enable relationships and synergy to grow. If people do not know each other, perhaps fear each other, and do not trust each other, synergy be will difficult to develop, and complexity will be difficult to defeat.

At the team level, it is the project leader’s responsibility to encourage positive behaviors—those that lead to successful outcomes; and discourage negative behaviors—those that lead to project failures. These behaviors include not only technical performance, but also behaviors that lead to the establishment and enhancement of relationships that lead to synergies—synergies that will enable team members to overcome complexity and drive project initiatives toward meeting the mission requirements and achieving the projected vision.

I once managed a large IT operations program for a US government agency. The program had over a dozen team leaders, each leading teams of between five and fifteen administrators and analysts. Within a month of starting the position, I conducted a leadership questionnaire to get an understanding of the leadership and management training these team leaders had received. The results were all over the map—some were trained and experienced leaders, others had never attended any leadership training. Some of the team leaders who had no leadership training had complaints from the customer because of their poor communications. Some of them had team members that were not happy. Most of them had accountability issues—they were not accountable and they did not hold their people accountable. As a result, morale was low and our customer was not satisfied.

I responded by developing and communicating a strategic vision of the program, establishing initiatives for the calendar year. I documented leadership and management standards for each team leader in the program. I met with them individually in order to build relationships and to gain an understanding of the issues they faced. I made myself available to speak with them whenever they needed assistance. I established quarterly awards for Valor, Customer Service, and Leadership, recognizing personnel that exemplified the behavior we needed in order to improve. I met with them as a group on a weekly basis, facilitating resolution of issues and providing leadership training. I established a system consisting of team assessments, analysis of those assessments to identify strengths and weaknesses, and team planning to bolster strengths and reduce weaknesses. Instead of providing them leadership briefings every week, the system required the team leaders to brief their groups on the status of implementing their plan. During these briefings, the team leaders received feedback from their peers on how to deal with operations, customer, and personnel issues and how to improve morale. They learned to be better communicators. Through this process, the team leaders obtained on-the-job training in leadership, IT operations continuously improved, and morale issues were identified and addressed.

Now that you have an introduction to leadership, let’s explore the career of a great geek leader to understand how you can become one yourself.

William Henry Gates III is the epitome of a great geek leader. He is a geek’s geek, a highly intelligent and voracious learner, nurtured on technology, driven to solve the most complex problems. Bill demonstrated core leadership skills early in his career. He then practiced exemplary leadership skills as he built Microsoft into the world’s largest software company.

Bill Gates was first exposed to computers in 1968 when he was only 13 years old. He attended Lakeside School, an all-male institution with grades seven through twelve in Seattle, Washington, USA. The Mothers’ Club at Lakeside used the proceeds from a rummage sale to buy an ASR-33 Teletype terminal and computer time on a General Electric mainframe (Andrews and Manes, 2013). “The Lakeside’s Mothers’ Club had a rummage sale every year to raise money for the school,” Gates said in a 2010 interview. “And instead of just funding the budget, they always would fund something kind of new and interesting in addition. And without too much understanding, they decided having a computer terminal at the school would be a novel thing. It was a teletype—upper case only, ten characters a second—and you had to share a phone line to call into a big time-sharing computer that was very expensive. When you were connected up it would charge, and then when you actually had a program running it would charge a lot more.” It was here that Gates learned to program in BASIC. “The programming language was BASIC, which was quite novel at the time. It had been invented by some Dartmouth professors. So that was the first computer language I learned, and I wrote increasingly complex programs. So that eighth grade exposure was a pretty neat thing, even though the machine we were working on was quite limited” (Academy of Achievement, 2010).

Gates and his classmates in the Lakeside Computer Club, including Paul Allen, who co-founded Microsoft with Gates, eventually wrote a complex class scheduling system for the Lakeside School. (Lakeside had asked some adults to write the program, but they could not figure it out.) After completing this project, the students wrote a payroll application for the Computer Center Corporation (C Cubed) in exchange for computer time. “So we agreed to write this payroll program,” Gates explained. “And a payroll program is surprisingly complicated. There’s all these taxes and reports and things at the state level and federal level (Academy of Achievement, 2010).” This experience exposed Gates to the inner workings of a business at a very young age.

C Cubed asked Gates and his friends if they could find problems with the Digital Equipment Corporation computer that the company rented. “These C Cubed people have this computer, which is a time-sharing computer, and they’re letting us come in at night,” Gate explained. “And they had this deal with the company who made the computer, Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), that they had this acceptance period. If they could find problems with it, they could delay their rental payments. So they thought of us as kind of monkeys that might find some problems and help them delay their rental payments. Well, that was a fair analysis, because at first we were just completely goofing around. Like, we’d try to run hundreds of jobs at the same time, or have all the jobs try and grab the same resources, to see if we could get the system to fail. And we did, in kind of this brute force approach. So they would report that as a problem and delay their rental payment. Well, a few months went by, actually about four months by the end of it. We had gotten very sophisticated. In fact, we’d gotten the source code of the operating system out of the garbage can, and were reading it, and the kind of problems we were finding were far more subtle. In fact, we would not only find the problem, we’d look and we’d suggest how they might fix it” (Academy of Achievement, 2010).

The team’s exploits gained them a reputation at DEC, and when TRW needed top programming talent for a large DEC PDP-10 and PDP-11 programming project at the Bonneville Power Administration in Vancouver, Washington, USA, DEC recommended Gates and Allen (Andrews and Manes, 2013). “I was 16 when they interviewed me,” Gates explains. “So they were like, ‘We can’t hire you.’ But then they talked to us about software and we clearly know a lot. And when you’re young and you know a lot, people don’t have any kind of intermediate thing. You’re either what you’re supposed to be, which is a kid that doesn’t know that much, or they think, ‘Whoa, this guy is the limit!’ We were pretty good programmers. But anyway, so we got jobs at this TRW and that exposed me to some programmers, who were way better than I was, who critiqued my work. I could look at their work.”

It is widely known that Gates attended Harvard and left the university to start Microsoft. But Gates was a geek’s geek, a proven problem solver prior to even being accepted at Harvard.

While at Harvard, Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS) created the Altair 8800 based on Intel’s 8800 chip. However, the machine did not ship with software, and no one at MITS had time to develop it. Gates and Allen called MITS and said they had an installation of BASIC that would run on the new Altair 8800. When they made the call, the software did not exist. They had six weeks to develop it. Allen built an Altair 8800 simulator based on previous work they had done with an Altair 8080 (Andrews and Manes, 2013). “So I’m a student at Harvard,” Gates explained. “Paul’s working at Honeywell, but we spend—what was it?—six weeks, and really write this thing, which—you know, my whole career has sort of been building after this thing. It’s one of the most—probably the most fun piece of software I ever wrote. I mean, it’s unbelievable, because it has to be very small—there’s only 4K bytes of memory—and we don’t have the real machine, so you have to be very careful you get everything right. Anyway, so Paul takes it out, and these guys mostly sell kit computers, they’d only assembled a few of them, and so they got it connected up and Paul puts it in and it runs the first time!” (Academy of Achievement, 2010). Gates left Harvard, Gates and Allen signed a contract with MITS, and Microsoft was born!

In the early years at Microsoft, Bill Gates developed and refined his core leadership skills as demonstrated through his strategy, action, and results.

Strategically, Gates defined the Microsoft vision as “a computer on every desktop and in every home, running Microsoft software” (Andrews and Manes, 2013). Gates always had the big picture in mind, yet he kept an eye on every detail of the business. He planned a strategy in the early years that Microsoft still uses very effectively today. “Microsoft was only a few people and we’d written this BASIC, and the idea was to license it to lots of companies and then to write other software. So the head of MITS said he could help us market it to other people and take a sales commission for that, and I wrote the contract so that if they weren’t serious about promoting it and putting a lot of investment into that, they would lose that right” (Academy of Achievement, 2010).

Recognizing that software piracy was eroding Microsoft profits, Gates demonstrated the courage to lead, writing an open letter to the Altair computer users group that discouraged the pirating of the Altair BASIC software Microsoft developed. “Most directly, the thing you do is theft,” Gates wrote (Andrews and Manes, 2013).

Bill Gates took action in the early days of Microsoft. He made the decision to purchase 86-DOS from Seattle Computer Products and then license it to IBM just in time for the release of the IBM Personal Computer (PC), capitalizing on an opportunity to position tiny Microsoft predominately with giant IBM (Andrews and Manes, 2013).

Gates, an effective communicator, became the chief spokesman for Microsoft, constructing business deals with partners such as Apple and Texas Instruments and making sales to customers. His efforts mobilized others to follow his lead, all in pursuit of a single vision—a computer on every desk in every home running Microsoft software. Gates achieved results through risk taking, staying focused, and being agile. The software that Microsoft released was not always free of bugs, but Gates took the risk and released it regardless. He did not give up when he received poor reviews; instead, he stayed focused on results. Word 3.0 was a great example. Word 1.0 and Word 2.0 were riddled with bugs, but Microsoft listened to the customer, remained focused, and developed Word 3.0—which unseated Corel WordPerfect, the leading word processor since 1979—as the dominant word processor in the industry in 1992 (Andrews and Manes, 2013).

Windows development took a similar path. When Windows 1.0 was released in 1985, it was not successful, but Gates was not deterred. Microsoft released Windows 2.0 in 1987, which did better, but was not widely successful. In 1990, Microsoft released Windows 3.0, and the company finally achieved a breakthrough, selling 10 million units in two years and raking in millions in profits. This is an example of resiliency, the determination to continue to pursue a vision in the face of obstacles (Chandomba, 2014).

Microsoft demonstrated agility by developing the capacity to excel not only in the areas of programing languages, but also in operating systems and productivity applications. Their actions, led by Gates, enabled attainment of their vision (Andrews and Manes, 2013).

2.3 Transformational Leadership

Businessdictionary.com defines transformational leadership as a “style of leadership in which the leader identifies the needed change, creates a vision to guide the change through inspiration, and executes the change with the commitment of members of the group” (Transformational Leadership, n.d.). In 1983, Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner of Santa Clara University started researching thousands of personal best leadership experiences. Their research included 75,000 people from all over the world. They used this research to develop their Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership Model. This transformational leadership model consists of these five elements: Model the Way, Inspire a Shared Vision, Challenge the Process, Enable Others to Act, and Encourage the Heart. Bill Gates’s leadership at Microsoft not only transformed the computer industry, it also transformed the business world. Table 2-2 demonstrates Gates’s exemplary transformational leadership impact based on Kouzes and Posner’s model (Kouzes and Posner, 2010).

Table 2-2 Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership Model

Element | Description | Gates’s Behavior |

Model the Way | The leader is clear about his/her values and philosophy, setting a positive example. | Bill Gates was an expert programmer. He worked long hours and rarely took vacations. He expected his employees to show the same commitment. |

Inspire a Shared Vision | The leader creates a compelling vision that drives people’s behavior to achieve the goals. | Microsoft employees were inspired by Gates’s vision of ruling the microcomputer software world. |

Challenge the Process | The leader is willing to change the status quo and take risks, stepping out into the unknown as pioneer. | No other company shared Gates’s vision for writing software for inexpensive microcomputers. Ken Olsen, the president of Digital Equipment Corporation, a company Gates admired, thought the notion that people would want to have a computer was “silly” (Academy of Achievement 2002). |

Enable Others to Act | The leader is effective at working with people. The leader values teamwork and collaboration. | Although Gates has a tough and challenging management style, his employees respected him and were compelled to follow his leadership. |

Encourage the Heart | The leader recognizes and rewards team members for their contributions and accomplishments toward achieving the vision. | Bill Gates rewarded his employees with excellent pay and recognition. Many Microsoft employees became millionaires during their tenure with the company. |

Data derived from Northouse (2007). Leadership: Theory and Practice. London, UK: Sage.

Bill Gates was an effective communicator who kept his employees motivated. He invested in their future and made many of them wealthy. He delivered the right information to the right people for the right purpose. “The vision is really about empowering workers,” Gates said, “giving them all of the information about what’s going on so they can do a lot more than they’ve done in the past” (Chandomba, 2014).

When it comes to IT geeks in leadership positions, Bill Gates is the exception, not the rule. Considering the traits and behaviors of effective leaders, most geeks face more challenges that hinder their ability to lead than they have intrinsic capabilities for leadership. Studies have shown that IT geeks (1) are generally not visionary, an attribute that is key to effective, transformational leadership (Lounsbury et al., n.d.); (2) are generally introverted, preferring to work alone, which makes motiving others and being an effective communicator difficult if not impossible (Institute for Management Excellence, 2003); (3) are generally not conscientious, meaning they have an inclination to disregard rules, norms, and values (Lounsbury et al., n.d.); (4) are not concerned about image management, which makes modeling the way a challenge (Lounsbury et al., n.d.); and (5) generally prefer thinking to feeling, which makes leading from the heart challenging (Institute for Management Excellence, 2003).

There are three personality preferences that give IT geeks hope to become effective leaders: (1) IT professionals are predominantly thinkers, a trait they share with people in management and executive positions; (2) two thirds of IT geeks prefer judging over perceiving, meaning they are generally decisive and organized; and (3) some IT geeks have intuition, and therefore have the ability to think strategically and systematically (Institute for Management Excellence, 2003). IT geeks are also emotionally resilient, open to change and new ideas, intrinsically motivated, and tough minded (Lounsbury et al., n.d.).

Let’s explore a few studies that produce these findings.

2.4.1 The Big Five Personality Traits

In the 1970s, two independent research teams studied personality traits of thousands of people and found the same results. The first team was Paul Costa and Robert McCrae at the National Institutes of Health, and the second team was Warren Norman of the University of Michigan and Lewis Goldberg of the University of Oregon. Analysis of each team’s data revealed that most human personality traits, regardless of language or culture, fall within five dimensions, known as the Big Five: Agreeableness/Teamwork, Conscientiousness, Emotional Resilience/Neuroticism, Extraversion, and Openness (The Big Five Personality Test, n.d.).

John Lounsbury of the University of Tennessee, R. Scott Studham of Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Robert Steel of the University of Michigan, and Lucy Gibson and Adam Drost of eCareerFit.com conducted a study of 9,011 IT professionals, extracting data from eCareerfit.com’s archival database, a database that included 2,000 unique IT job titles (Lounsbury et al., n.d.). Their study analyzed IT professionals according to the Big Five personality traits. In addition, because the Big Five traits were deemed to be too broad, they included seven narrow-scope personality constructs in their analysis: Assertiveness, Customer Service Orientation, Intrinsic Motivation, Image Management, Optimism, Tough-Mindedness, and Visionary Style. For these 12 factors, they compared the results for IT professionals against 200,000 individuals from all occupations in their database to determine how those traits related to career satisfaction. The study examined two research questions:

1. On which personality traits do IT professionals differ from other occupations?

2. Which personality traits are related to career satisfaction for IT professionals?

Their findings are summarized in Table 2-3.

In 2002, another group of researchers (Timothy A. Judge, University of Florida; Joyce E. Bono, University of Minnesota; Remus Ilies, University of Florida; and Megan W. Gerhardt, University of Iowa) analyzed 78 leadership and personality studies published between 1967 and 1998 against the Big Five traits. They found that extraversion was the factor most strongly related to leadership, followed by conscientiousness, emotional resilience, and openness. Agreeableness was only weakly associated with leadership (Northouse, 2007).

Table 2-3 Big Five Personality Traits Study Results

Personality Trait | Description | Finding |

Big Five: | ||

Agreeableness/Teamwork | Propensity to work as part of a team and cooperatively function on group efforts. | IT professionals’ mean scores not significantly different from norm group. |

Conscientiousness | Dependability, reliability, trustworthiness, and inclination to adhere to company rules, norms, and values. | IT professionals’ mean scores were BELOW other occupations. |

Emotional Resilience | Overall level of emotional resilience in the face of job stress and pressure. | IT professionals had significantly HIGHER mean scores compared to other occupations. |

Extraversiona | Tendency to be sociable, outgoing, gregarious, expressive, warmhearted, and talkative. | IT professionals’ mean s Mission Viejo, CA: Toastmasters International. cores not significantly different from norm group. |

Openness | Receptivity/openness to change, innovation, novel experience, and new learning. | IT professionals had significantly HIGHER mean scores compared to other occupations. |

Narrow-Scope: | ||

Assertiveness | Disposition to speak up on matters of importance, express ideas and opinions confidently, defend personal beliefs, seize the initiative, and exert influence in a forthright but not aggressive manner. | IT professionals’ mean scores not significantly different from norm group. |

Customer Service Orientation | Striving to provide highly responsive, personalized, quality service to customers, putting them first, and trying to make them feel satisfied. | IT professionals had significantly HIGHER mean scores compared to other occupations. |

Intrinsic Motivation | Disposition to be motivated by intrinsic work factors such as challenge, meaning, autonomy, variety, and significance. | IT professionals had significantly HIGHER mean scores compared to other occupations. |

Image Management | Disposition to monitor, observe, regulate, and control the self-presentation and image projected during interactions with others. | IT professionals’ mean scores were BELOW other occupations. |

Optimism | Have an upbeat, hopeful outlook concerning people, situations, prospects, and the future, even in the face of difficulty and adversity; a tendency to minimize problems and persist in the face of setbacks. | IT professionals’ mean scores not significantly different from norm group. |

Tough-Mindedness | Appraise information, draw conclusions, and make decisions based on logic, facts, and data rather than on feelings, values, and intuition; disposition to be analytical, realistic, objective, and unsentimental. | IT professionals had significantly HIGHER mean scores compared to other occupations. |

Visionary Style | Focusing on long-term planning, strategy, envisioning future possibilities and contingencies. | IT professionals’ mean scores were BELOW other occupations. |

a This is a career satisfaction study. Extraverted IT professionals are as satisfied with their careers as extraverts in other occupations. However, two-thirds of IT professionals are considered introverts (Institute for Management Excellence, 2003).

Data derived from Lounsbury et al. (2009). “Personality Traits and Career Satisfaction of Information Technology Professionals.” eCareerFit.Com.

2.4.2 Myers-Briggs Type Indicator Study

Katherine Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers, developed the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) instrument in the 1940s. MBTI is based on the work of Carl Jung, a Swiss-born psychiatrist who researched and published studies on psychological types in the 1920s. The instrument was designed to determine individual preferences and to promote more constructive use of differences among people. MBTI test results enable organizations to assign personnel to tasks that fit their abilities. It is one of the most widely known psychological instruments today and is used all over the world (Kroeger, Thuesen, and Rutledge, 2002).

The MBTI instrument analyzes our preferences using four dichotomies: Energy, Information, Decision, and Action. Each dichotomy consists of two personality areas. Energy and Action are attitudes observed by the outside world. Information and Decision are internal processes that we use to make sense of the outside world. The preferences are not right or wrong, good or bad. They are our inclinations, our first choice in our approach to dealing with the world.

• Energy. Extraverts (E) receive their energy from their experiences with people. They refuel through personal interaction. Introverts (I) focus internally and are energized through their own internal experiences.

• Information. People with a Sensing (S) preference make sense of the world using their five senses. People who prefer iNtuition (N) understand the world through insight.

• Decision. Those who prefer Thinking (T) make decisions based on logic and principles, whereas those who prefer Feeling (F) make decisions based on personal and social values.

• Action. If one’s preference is Judging (J), this person likes a structured approach, living life in a controlled way. Those who prefer Perceiving (P), on the other hand, are spontaneous and open ended in their approach to life (Hewertson, 2015).

The MBTI instrument assigns a four-letter type indicator that summarizes an individual’s preference. For example, ESFP indicates an individual with a preference for Extraversion, Sensing, Feeling, and Perceiving (Kroeger et al., 2002).

Individuals develop preferences early in life, and these preferences usually do not change. We become comfortable with our preferences, which allows us to cope with confidence in this complex world. We are capable of using our non-preferences when necessary, and as we mature, our non-preferences enhance our ability to perform in new ways. But our non-preferences do not become our preferences, just has left-handed people do not become right-handed people (Kroeger et al., 2002).

Right-handed people can learn to write with their left hand, but it takes hard work and a lot of practice. I have known programmers that prefer Visual Basic over C#, and programmers that prefer C# over Visual Basic. Give them the same requirements, and each of them was capable of writing excellent code to solve a problem in a reasonable amount of time. They did it in their own way using their preferred development language. Could the C# programmer write code in Visual Basic, or the Visual Basic programmer develop solutions in C#? Absolutely! But it would take more time and more effort for them to write code in their non-preferred languages. You can think of the Myers Briggs Type Indicators in the same way.

Tables 2-4 through 2-6 contain a summary of MBTI and a comparison of the MBTI scores of the general population verses IT professionals. If you have never taken an MBTI test, write down the temperament preference that agrees with you as you read the descriptions.

In contrast to the findings of Judge et al. (Northouse 2007) concerning leadership and extraversion, MBTI studies of IT professionals have found that two-thirds of IT geeks are introverted. This comes as no surprise to anyone that has spent time with IT geeks. IT geeks are generally less extraverted and more introverted than the general population. According to Carl Jung, the preference between introversion and extraversion is the biggest discriminator among people (Kroeger et al., 2002).

As discussed earlier, researchers have found that extraversion is the most important trait of the Big Five concerning leadership. This finding puts most IT geeks at a disadvantage when it comes to being an effective leader.

Generally, introverted people are more comfortable working alone than in groups and find themselves drained after prolonged social interactions (Kroeger et al., 2002). Such a predilection does not lend itself well to being a strong communicator or motivator. These introverted geeks must work hard at communication and motivation tasks; they generally don’t like those tasks, and those tasks don’t come naturally to them.

Introverts are energized by their own thoughts, ideas, and concepts and are generally not motivated to influence others. As discussed earlier, leaders are required to motivate and influence their team members. IT geeks in leadership positions generally are challenged when it comes to motivating others.

Introverts generally require time to think about situations before making decisions (Kroeger et al., 2002). This predilection may put IT geek leaders at a disadvantage when the situation requires a quick decision.

Leaders are expected to model the way, to set a positive example. Considering the Big Five study results, IT geeks scored below the norm on image management, indicating a lack of concern for projecting a smooth, polished self-presentation in interpersonal settings. IT geeks that do not care about their appearance will have a difficult time attracting followers. Their predilection for poor image management is likely related to their introverted inner focus and lack of conscientiousness. Non-geek leadership will frown upon a geek leader who does not monitor the image he or she portrays.

As Erika Andersen stated (Andersen, 2012b), most of us can learn to be more effective leaders. IT geeks can learn to use their less-preferred extraverted style just as a Visual Basic programmer can learn to code in C#. It may take some effort, but you can learn to lead out loud!

Table 2-4 MBTI Extraversion and Introversion Study Results

Temperament Preferences | General Population (CAPT Study) | General Population (Keirsey/Myers) | Computer Professionals (Management) |

Extraversion (E): | 54% | 75% | 33% |

Need for sociability; energized by people and contact with lots of people | |||

Prefers to work with other people (teams, parties, gatherings, work groups) | |||

Speaks first, thinks later | |||

Finds listening more difficult than talking | |||

Needs affirmation from others to feel confident in own performance | |||

Introversion (I): | 46% | 25% | 67% |

Territorial—needs own private space; drained by a lot of people contact | |||

Prefers working alone (reading, writing, studying) or working with a limited number of people | |||

Prefers depth over breadth | |||

Rehearses things before saying them | |||

Perceived as a “great listener” | |||

Believes “talk is cheap,” respects people who use words efficiently |

Data derived from Institute for Management Excellence. (2003). “Differences between ‘Computer’ Folks and the General Population.” itstime.com; and Kroeger, et al. (2002). Type Talk at Work. New York, NY: Dell.

Table 2-5 MBTI Sensing and Intuition Study Results

Temperament Preferences | General Population (CAPT Study) | General Population (Keirsey/Myers) | Computer Professionals (Management) |

Sensing (S): | 54% | 75% | 46% |

Practical and realistic; wants facts, trusts facts, and remembers facts | |||

Focuses on details and may miss the big picture | |||

Focuses on the external (what is observed); does not use or trust intuition | |||

Likes to focus on the moment; would rather take action than think about taking action | |||

“Fantasy” is a dirty word; “seeing is believing” | |||

Intuition (N): | 46% | 25% | 54% |

Innovative; seeks a better way | |||

Wants ideas; likes metaphors and vivid imagery | |||

Focuses on the internal (own inner voice); may find ideas coming to them with no idea of where they come from | |||

Thinks about several things at once | |||

Believes time is relative | |||

Gives general answers to questions instead of specifics |

Data derived from Institute for Management Excellence. (2003). “Differences between ‘Computer’ Folks and the General Population.” itstime.com; and Kroeger, et al. (2002). Type Talk at Work. New York, NY: Dell.

Table 2-6 MBTI Thinking and Feeling Study Results

Temperament Preferences | General Population (CAPT Study) | General Population (Keirsey/Myers) | Computer Professionals (Management) |

Thinking (T): | 41% | 50% | 81% |

More comfortable with impersonal, objective judgments; makes decisions based on logic and objectivity | |||

Prefers and follows rules, principles, laws, criteria | |||

Good at logical arguments | |||

Stays calm in situations in which others are upset | |||

Will argue both sides of a discussion | |||

Believes it is more important to be right than to be liked | |||

Feeling (F): | 59% | 50% | 19% |

More comfortable with value judgments, may be put off by rule-governed choices | |||

Makes decisions based on personal preferences and others’ feelings | |||

Good at persuasion | |||

Will over-extend personally to accommodate others | |||

Easily takes back comments that may offend others | |||

Empathetic toward others |

Data derived from Institute for Management Excellence. (2003). “Differences between ‘Computer’ Folks and the General Population.” itstime.com; and Kroeger, et al. (2002). Type Talk at Work. New York, NY: Dell.

IT geeks are generally less sensing and more intuitive than the general population. There are slightly more IT geeks who prefer intuition over sensing.

IT geeks in leadership positions with a preference for sensing have a natural sense of the movement of time (Kroeger et al., 2002). While not an identified leadership trait, this is an advantageous preference for estimating how long tasks and projects will take.

IT geeks with a preference for sensing tend to focus on individual pieces of the puzzle instead of the picture the completed puzzle produces. For geek leaders, this can be a disadvantage. There could be a tendency to fix what is seen as individual performance issues rather than take actions that motivate and energize the entire team to work together to reach a goal.

Leaders who prefer intuition have no problem seeing the picture, but may not see how all of the puzzle pieces fit together. They easily see patterns and future possibilities. For IT geek leaders with this preference, intuition is a strength that enables them to think strategically and systematically, to create a vision for the future of their team and project. It enables them to use their vision to drive creative change. Unfortunately, almost half of IT geeks tested did not have this preference.

Bill Gates’s ability to simultaneously conceive and pursue a big-picture vision, a computer on every desk in every home running Microsoft software, and to be as detailed oriented as necessary to write great software, is extraordinary.

IT geeks prefer thinking much more than the general population does. There are far more thinkers than feelers in the IT profession.

Cross-cultural research has shown that thinkers make up about 86% of middle managers, 93% of senior managers, and 95% of executives. Leaders of all temperaments tend to clone themselves, hiring and nurturing other leaders who think as they do (Kroeger et al., 2002).

Because IT professionals are predominantly thinkers, this trait is an indicator that IT professionals have the ability to advance within their organizations if they can develop other complimentary leadership skills and if they can overcome their natural leadership challenges.

From a thinker’s perspective, the world is a series of problems to be solved (Kroeger et al., 2002). IT geeks solve technical problems for a living, and IT geek leaders with a thinking preference are driven to solve problems with little regard to the human element. They may come across as critical and harsh concerning their subordinates’ performance. As discussed earlier, this preference makes encouraging the heart a challenge for IT geek leaders.

Whereas MBTI studies may show that IT geeks prefer thinking over feeling, this does not make geeks more intelligent than people who prefer feeling over thinking, and it does not mean that IT geeks do not have emotions. It does mean that IT geeks prefer thinking over feelings when they make decisions. Instead of preferring to make a decision based on what people care about and their different points of view, IT geeks generally prefer to look at the principles that are applied and to analyze the pros and cons. Instead of being primarily concerned about values and what is best for the people involved, IT geeks generally prefer to be logical and impersonal.

Dale Carnegie first published How to Win Friends and Influence People in 1937, and the lessons taught in that book are still relevant today. Part Two of the book is called “Six Ways to Make People Like You” (Carnegie, 2010). The six principles Carnegie presented are summarized in Table 2-7.

Table 2-7 Dale Carnegie’s Six Ways to Make People Like You

# | Principle | Quote |

1 | Be genuinely interested in others. | “It is the individual who is not interested in his fellow men who has the greatest difficulties in life and provides the greatest injury to others. It is from among such individuals that all human failures spring.” |

2 | Smile. | “Action seems to follow feeling, but really action and feeling go together; and by regulating the action, which is under the more direct control of the will, we can indirectly regulate the feelings, which are not.” |

3 | Remember that a person’s name to that person is the sweetest and most important sound in any language. | “Franklin D. Roosevelt knew that one of the simplest ways of gaining good will was by remembering names and making people feel important—yet how many of us do it?” |

4 | Be a good listener. Encourage others to talk about themselves. | “Isaac F. Marcosson, a journalist who interviewed hundreds of celebrities, declared that many people fail to make a favorable impression because they don’t listen attentively. ‘They have been so much concerned with what they are going to say next that they do not keep their ears open.… Very important people have told me they prefer good listeners to good talkers, but the ability to listen seems rarer than almost any other good trait.” |

5 | Talk in terms of the other person’s interests. | “For Roosevelt knew, as all leaders know, that the royal road to a person’s heart is to talk about the things he or she treasures the most.” |

6 | Make the other person feel important—and do it sincerely. | “The unvarnished truth is that almost all the people you meet feel themselves superior to you in some way, and a sure way to their hearts is to let them realize in some subtle way that you recognize their importance, and recognize it sincerely. Remember that Emerson said: ‘Every man I meet is my superior some way. In that, I learn from him.’” |

Data derived from Carnegie, D. (2010). How to Win Friends and Influence People. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

IT geeks generally do not try to appear caring, warm, or tactful—this disposition is not their first preference. Instead they generally prefer to be impersonal, to avoid allowing their personal wishes or other people’s wishes to influence their decisions. This general preference makes leading by encouraging the heart very challenging for IT geeks.

As Bill Gates has shown, IT geeks are capable of encouraging the heart, but they need to be cognizant of the disparity between their personal preference and the behavior required and expected of effective leaders.

IT geeks generally prefer judging over perceiving more than the general population does. As described in Table 2-8, two-thirds of IT geeks tested prefer judging over perceiving.

This general preference toward judging gives IT geeks a leadership advantage. Leaders are expected to establish plans for their teams and manage the implementation of those plans. They need to be decisive and to work hard to set a positive example. IT geeks with a preference toward judging are capable of leading in this way.

Keirsey.com lists Bill Gates as an INTJ (Rational™ Portrait of the Mastermind, n.d.), meaning that he is an Introvert (I) verses an extrovert and he prefers Thinking (T) over feeling. Yet Gates is a visionary, an effective communicator and motivator, and he has demonstrated that he encourages the heart. He is proof that IT geeks can come to be great leaders, and he sets the example for other IT geeks, demonstrating how they can adapt their preferred style and make a difference for their team, their project, their organization, and maybe even the IT industry and the business world.

Table 2-8 MBTI Judging and Perceiving Study Results

Temperament Preferences | General Population (CAPT Study) | General Pop. (Keirsey/Myers) | Computer Professionals (Management) |

Judging (J): | 54% | 50% | 66% |

Likes closure and solid plans, goals, and timetables | |||

Work comes before play | |||

Likes to make decisions and move on and to complete things and get them out of the way | |||

Organized: keeps things in order | |||

Does not like surprises | |||

Perceiving (P): | 44% | 50% | 34% |

Likes open and fluid options | |||

More playful and less serious; work does not always come first; work must be enjoyable | |||

Likes to keep options open and explore; resists making final decisions | |||

Easily distracted | |||

Prefers creativity and spontaneity to neatness and order | |||

Changes the subject often during conversations |

Data derived from Institute for Management Excellence. (2003). “Differences between ‘Computer’ Folks and the General Population.” itstime.com; and Kroeger, et al. (2002). Type Talk at Work. New York, NY: Dell.

The differences in personality preferences are the source of miscommunications, politics, interpersonal conflicts, and the like. But if everyone were an introvert, our projects would not benefit from ideas generated in lively brainstorming sessions fueled with the energy of extraverts. And, if everyone were an extravert, our projects would not benefit from the introvert’s deep thinking and listening skills required to develop solutions. Each temperament preference brings its own strengths, and as leaders, we must manage the inevitable conflict among people with different styles and leverage their ability to contribute to the success of our projects.

2.5 Information Technology Projects are Different

IT projects are sickly creatures, prone to ailments that threaten their survival. If you are an IT project leader, your project may be at risk of failing.

Since 1985, The Standish Group has documented success and failure rates of real-life IT environments and software development projects. The group produces the CHAOS Manifesto, which is based on research that encompasses 90,000 completed IT projects over 18 years. Sixty percent (60%) of the projects analyzed for the CHAOS Manifesto are US based, 25% are European, and the remaining 15% represent the rest of the world.

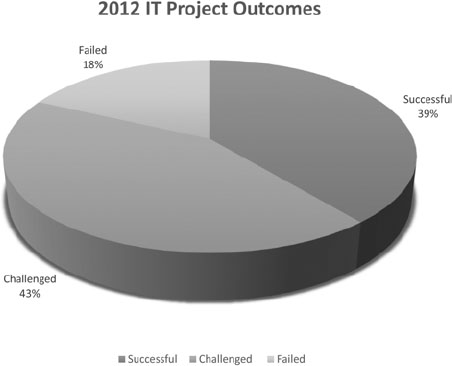

Figure 2-1 2012 IT project outcomes. (Data derived from The Standish Group International. “The CHAOS Manifesto 2013: Think Big, Act Small.” Versionone.com.)

According to the CHAOS Manifesto 2013 (see Figure 2-1), 39% of all projects were successful, meaning they were delivered on time, on budget, with required features and functions; 43% were challenged, meaning they were late, over budget, and/or provided less than the required features and functions; and 18% failed, meaning they were cancelled prior to completion or delivered and never used (The Standish Group International, 2013). Experts estimate the global cost of IT failure to be $3 trillion annually (Krigsman, 2012).

If the civil engineering community experienced the same statistics, 43% of housing would be substandard and 18% of houses would be unfinished, littering our cities and towns with ramshackle buildings. If the IT projects were patients, they would have a survival rate of 39%, a chance of becoming sick of 43%, and an 18% chance of dying.

2.6 Why Are IT Projects So Sickly?

Although not as complex as the human body, IT projects are born and raised in an environment with its own inherent complexities.

According to Robert Goatham of Calleam Consulting Ltd, IT projects are complex because of the number of interrelated decisions that are required in order for the project to be successful. Goatham reports that IT projects require practitioners to expend over five times as much effort making decisions as civil engineering practitioners expend on making decisions for construction projects (Goatham, 2009).

The environments in which IT projects are developed and deployed exacerbate the complexity. “While it would be comforting to think that all decisions are made in a fully rational and informed way, in practice many other dynamics influence the way decisions are made,” Goatham writes. “Diverse factors such as cognitive biases, training, prior experiences, interpersonal relationships and personality type can shape the decisions made on an individual basis and in the broader context factors such as politics, organizational goals (both spoken and unspoken) and the structure of incentives within the organization can also influence the choices that get made. When other environmental factors that affect decision making (such as the amount of schedule or budget pressure the team is working under) are considered, it becomes clear that the domain within which decisions are made is an extremely complex one and that complexity brings with it the ever present danger of project failure” (Goatham, 2009).

According to the 2013 CHAOS Manifesto, “The real key to being a good PM is to take a complex process and make it simple and executable. Projects follow a natural progression. The PM’s job is to administer this progression to a successful resolution. The Standish Group research clearly shows that projects that have the leadership and judgment of a talented PM and an organization that supports its PM will fare much better than those that do not have such capability and posture in place” (The Standish Group International, 2013).

In the United States, the 2013 Healthcare.gov rollout is an excellent example of IT project failure due to extreme complexity. Healthcare.gov was one of the most complex IT projects ever undertaken by the US federal government. It communicates in real time with about 112 different computer systems across the United States (Cha and Sun, 2013).

Heathcare.gov did not get exhaustive testing and had undergone late changes before its October 2013 release. The public found the site difficult to use, and it caused significant embarrassment for the Obama administration. CGI Group Inc, the contractor responsible for developing the site, said the government made late requirements changes, not providing the final requirements until May 2013. This lead to a requirement to rework about one-third of the development effort (Olsen, 2014).

Commenting on the complexity of Healthcare.gov and other government IT projects, Theresa Pardo, Director of the Center for Technology in Government at the University of Albany, State University of New York, said, “Greater complexity leads to greater risk. Most traditional system development efforts do not account for the level of coordination necessary in the development of such complex systems.… Our work shows, the more boundaries crossed, the more critical coordination becomes” (Newcombe, 2014).

As discussed in Chapter 1, managing this level of complexity requires excellent leadership. “Attention to the time and skills required for expert collaboration and coordination is often overlooked,” Pardo says. “You need ‘super’ project managers, who have the skill-sets to ensure all actions are coordinated across multiple boundaries and are sensitive to shifting realities” (Newcombe, 2014).

IT project leadership requirements are like the complex requirements human bodies have for antioxidants. In the human body, free radicals are atoms or groups of atoms that are formed when oxygen interacts with certain molecules. Free radicals can cause a chain reaction within the human body, damaging cellular components such as DNA or the cell membrane, causing cells to function poorly or to die.

The body’s defense system for free radicals is antioxidants. Antioxidants are molecules that interact with free radicals and terminate the chain reactions, preventing cellular damage and diseases such as cancer. The principle antioxidant micronutrients are vitamin E, beta-carotene, and vitamin C. The body cannot create the micronutrients—they must be supplied in the diet.

Complexity rampages through IT projects like free radicals. Complexity both damages projects at the lowest level, causing miscommunication and low morale, and hastens technological failure.

Antioxidants are composed of vitamin E, beta-carotene, and vitamin C. Similarly, the 2013 CHAOS Manifesto provides 10 success points that together make up a prescription for the leadership qualities needed in IT leaders. Table 2-9 details these success points and potential scotomas (blind spots) for IT project leaders—these blind spots impair the IT geek’s ability to successfully lead in the prescribed area. A subjective, nonscientific scoring of each CHAOS Manifesto Success Point against the Big Five Personality Trait Study and MBTI preference for IT professionals produces an IT geeks’ score of 0 out of 10 possible points. IT geeks are not natural leaders. They have to work hard to overcome their natural preferences—to gain sight in their blind spots—in order to become effective leaders. Just as antioxidants are required to combat free radicals at the atomic and molecular level, leadership is required to combat complexity at the project team level (see Figure 2-2).

Just as antioxidants are not found naturally in the human body, leadership is not found naturally in IT project teams. IT project leaders need the right diet. They need to feed their minds with the right information and change their behavior in such a manner that they strengthen their teams and protect their projects from failure.

Table 2-9 Project Leaders Success Points and IT Geek Temperaments

Success Point | Description | IT Geek Temperament | Score |

Point 1: Basic | Execute basic PM and process skills. | Strength: Per MBTI, Intuitive, Sensing, Judging, Thinking IT professionals have basic PM and process skills. | 1 |

Point 2: Executive bonds | Maintain a relationship with the Executive Sponsor. | Neutral: Per Big Five Study, IT professionals scored low on image management, which makes executive bonds challenging. IT professionals are not Feelers and are not adept at persuasion. IT Professionals are generally Thinkers, a trait shared with executives. | 0 |

Point 3: Details | Organize and manage details through planning, tracking, and controlling. | Strength: Per MBTI, strength for Sensing IT professionals. | 1 |

Point 4: Team leadership | Keep focus on main goal, think analytically, recognize and leverage team member potential. | Weakness: Per MBTI, weakness for introverted IT professionals which makes effective communications and motivation challenging. | −1 |

Point 5: Connections | Lead stakeholder communications that lead to successful resolution. | Weakness: Per MBTI, weakness for introverted IT professionals which makes effective communications challenging. | −1 |

Point 6: Ownership | Own the process for doing things well. | Strength: Per MBTI, strength for Intuitive IT professionals. | 1 |

Point 7: Bad news bearers | Deliver bad news early. | Weakness: Per MBTI, weakness for introverted IT professionals which makes effective communications challenging. | −1 |

Point 8: Business understanding | Envision project components and how the parts incorporate the business as a whole. | Weakness: Per Big Five Study, IT professionals scored low on visionary style and may have trouble thinking strategically. | −1 |

Point 9: Good judgment | Exercise the discipline, hard work, experience, and maturity required for sound judgment. | Neutral: Per MBTI, strength for IT professionals, however Big Five Study conscientiousness score threatens judgment. | 0 |

Point 10: Seasoned | Learn from mistakes and control resources to make timely corrections. | Strength: Per Big Five Study, strength for IT professionals as they have high emotional resilience, enabling them to bounce back from mistakes. | 1 |

Total | 0 |

Scoring model: 1, Strength; 0, Neither Strength nor Weakness; −1, Weakness

Data derived from: The Standish Group International. “The CHAOS Manifesto 2013: Think Big, Act Small.” Versionone.com.

Figure 2-2 Leadership is required at all levels in IT projects

While it is important that organizations provide training, just as individuals are responsible for eating a healthy diet, IT project leaders are responsible for their own leadership self-improvement.

This book is designed for you, the frontline IT geek leader faced with the challenge of healing and maintaining the health of a sickly IT project. You do not have to treat this patient alone. I am here to help you understand your patient’s ailments and to provide you the leadership prescription needed for preventive and responsive care.

2.7 We Need IT Geeks to Lead IT Geeks

Great leadership is required in order for information technology and computer engineering to gain the same type of standing in the world as civil or electrical engineering. Civil, electrical, and mechanical engineers have developed methods that enable consistent delivery of projects on time, within budget, and at the expected levels of quality and customer satisfaction. When is the last time you heard about a new building that collapsed or a new refrigerator that exploded? We take for granted that these solutions work.

As discussed, IT projects are complex, risky, and more prone to failure. The developers and technologists—the IT geeks who attempt to develop, deliver, and maintain these solutions—must be brave and emotionally resilient. They must be able to visualize a successful outcome and motivate their teams to fight through the setbacks and obstacles in order to achieve this success. IT geeks must care enough to understand the stakeholders’ feelings and desires, not just what makes sense to the geek’s logical mind. This requires IT geeks to behave in ways outside of their comfort zone. To some, it may not seem fair to require a geek to perform in a way that is contrary to his or her instincts in order for IT projects to be successful. Others, those of a determined ilk, those whose self-esteem and character will not allow them fail, will put on a hero’s cape and demonstrate the courage required for IT geek leaders.

I had an opportunity to lead with a very determined and agile group of IT technologists when I was the program manager for the US Air Force Digital Dental Radiography Solution (DDRS) Implementation Program. The goal of this program was to replace film-based X-rays with digital radiography at 77 US Air Force Active Duty Bases around the world and 24 US Air Force Reserves units in the United States. The program consisted of various component projects that were expected to deliver coordinated program benefits resulting from the deployment of servers, workstations, storage, software, digital sensors, digital panoramic radiographs, and other digital imaging devices at dental clinics and dental training facilities.

As a contract program manager, I led engagement efforts with the Air Force program sponsor, clinical lead, and other program management stakeholders prior to Request for Proposal (RFP) release to collaborate on the high-level program requirements and the intrinsic and extrinsic benefits that the program expected to deliver.

I established a Program Management Office (PMO), developing the vision, mission, goals, and objectives for managing the global deployment of the component projects and establishing the program management infrastructure to govern all the components. I developed the DDRS implementation program plan, documenting all the high-level planning elements, including roles and responsibilities, work breakdown structure, schedule management plan, communications plan, and risk management procedures.

In order to set expectations, I communicated the scope of the program to the clinic leaders and dental professionals, establishing boundaries for the products and services that were available in the program and those that were not. I performed this task by making use of a combination of various techniques: workshops, brainstorming sessions, presentations, etc. I took this opportunity to understand the voice of the stakeholders’ viewpoint and translate their expectations into reality within the grounds of the agreed contractual obligations. As the program manager, I understood how each piece fit into the DDRS puzzle. It was my job to communicate how each stakeholder, whether a supplier, engineer, sales person, logistics coordinator, web developer, trainer, or training video production staff—no matter which puzzle piece—fit into the overall DDRS picture.

This was a very complex program with many moving parts. Many of the disciplines involved were not accustomed to working together. For example, dentists and dental technicians don’t usually work with IT engineers. My leadership skills were challenged on many occasions. I led more conference calls and meetings during that four-year program than I can remember. As an introvert, this did not come naturally to me; facilitation was a skill I had to learn earlier in my career. It was a lot of hard work, but when the program was completed, we had successfully implemented a historic solution that touches every member of the US Air Force and their dependents around the world! Fortunately, I had several IT heroes on my team that refused to fail.

Dictionary.com defines a hero as someone who is of “distinguished courage or ability, admired for his [or her] brave deeds and noble qualities.” IT leaders must be heroes to their followers. They must be willing to sacrifice for the good of the customer, the organization, and their team members without expecting anything in return. They work hard to set an example by consistently sharpening their intellect, enabling themselves to handle complexity and to navigate through chaos and uncertainty. They willingly risk their hearts, demonstrating that they care for their people. They have the courage to consistently step outside of their comfort zone, being conscientious when their preference is to rebel, speaking out when their instincts are to internalize.

Chaos creates uncertainty. IT geek leaders must identify the uncertainty, uncover it, and take initiatives to resolve it. Geek leaders need to assemble teams of the right resources to address uncertainty and bring order to chaos. As a hero performs a heroic effort, a leader builds a system, working to bring order to chaotic situations, resolving uncertainties in the environment to deliver successful projects that satisfy customers.

IT leaders are motivated by these nobler causes. They have learned how to visualize a future status of success, how to build a strategy to achieve it, and how to articulate it to their followers in an inspirational way. In this group of followers, they recognize future leaders, detecting traces of a hero’s soul, and they purposefully empower, encourage, and mentor those future leaders. Their geek followers may have access to other leaders in the organization, those with oversight of their projects and performance, but they want to look up to their project leader—the leader who knows them best and who shares their backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences.

As an IT geek leader, you may be tempted to dive into the technical aspects of your project, but you have to focus on tasks that only you as a leader can do. Morale, coordination with senior leaders, strategic planning, rewards, discipline, accountability—these and many other leadership tasks take time and are your responsibility. Confine your work on technical problems to those that only you can solve. After you resolve the problem, obtain the resources and put a system in place that will allow you to delegate so that you will not have to resolve the next similar technical problem yourself.

There was LinkedIn post in a CIO group that invited comments concerning failed IT projects and the reasons for their failure. Some participants cited communications failures, others cited leadership failures. Their opinions are correct—leadership and communications failures, not only at the top of the organization, but also at the lowest leadership level, contribute to IT project failure. At this lowest level, we expect team leaders and project managers to be effective leaders, to overcome tremendous complexity; but as an industry, we do not provide the training required for them to be successful. If the cells of the body are compromised, the patient will be sick. This book equips the heroic IT geek to apply leadership at the cellular level. We can heal the cells by combating the free radicals of IT complexity, by learning to connect with people as well as we connect with technology. We can heal our patients, our IT projects, and be more successful more often.

IT geeks are some of the most brilliant people on the planet, having developed and delivered solutions that affect all of humanity. “Be nice to nerds,” Bill Gates said, “chances are you’ll end up working for one” (Walters, 2014). If you are an IT geek who is willing to put forth a hero’s effort, if you learn to overcome tendencies that impair your ability to lead, both geeks and non-geeks alike will gladly serve on your staff. In the next chapter, Emotionally Intelligent Communications, we will explore emotional intelligence, providing a framework for understanding yourself and your communication partners. Because communication is fundamental to effective leadership, I want to equip you to effectively send, receive, and understand information in a way that empowers you to influence people and situations.

Leadership Assessment Questionnaire

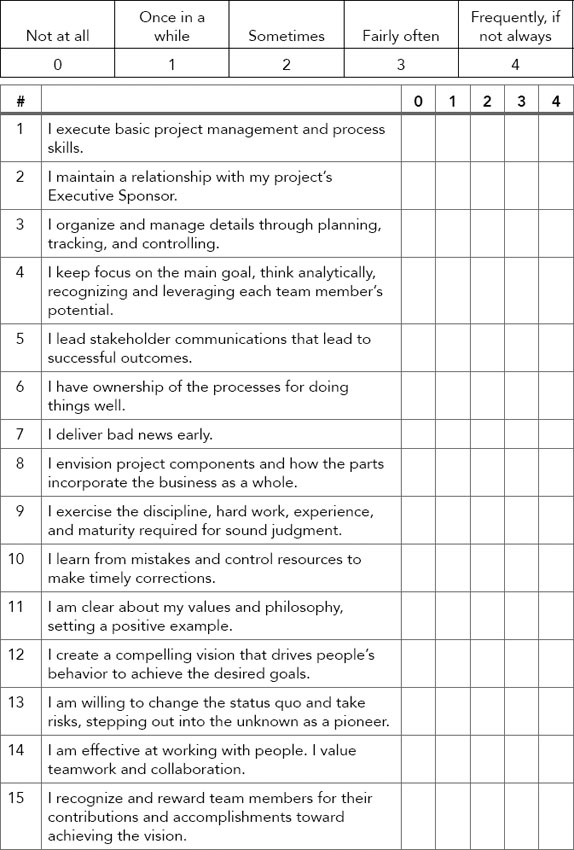

The statements in the questionnaire on the following page are designed to help you analyze your leadership style with respect to the 2013 CHAOS Manifesto 10 Success Points and the Five Practices of Exemplary Leadership. By thinking about your leadership performance with respect to these two models, you can get a sense of your own IT geek leadership strengths and weakness.

Leadership Assessment Questionnaire

Use the following key for this assessment: