Dale Carnegie wrote in How to Win Friends and Influence People, “Few people are logical. Most of us are prejudiced and biased. Most of us are blighted with preconceived notions, with jealousy, suspicion, fear, envy, and pride” (Carnegie, 1936). Sandy Allgeier, author of The Credibility Factor, wrote, “It can be very difficult to value others. Some ‘others’ are downright difficult people! A few are nasty, mean-spirited, and truly seem to enjoy hurting or harming others” (Allgeier, 2009). Brian Fitzpatrick and Ben Collins-Sussman used geek-speak to express a similar sentiment in Team Geek, in which they wrote, “People are basically a giant pile of intermittent bugs” (Fitzpatrick and Collins-Sussman, 2012). All of these authors recognized that people at every level—team members, colleagues, senior leaders, and stakeholders at large—are subject to human character frailties. These people make leadership challenging and sometimes perilous.

In Chapter 3, I discussed the importance of providing senior leaders with the ground truth concerning the actual circumstances of IT projects. The ground truth is unadulterated reality, delivered free of fear. The ground truth is what senior leaders need to know, not what others think they should know. It contains the facts in their purest form, not watered down by politics, misinformation, intentional ambiguity, or hidden agendas. Senior leaders with the ground truth have the facts and understanding they need to make decisions that lead to successful projects and organizations.

As project leaders, we may encounter another type of senior leader—those who who enjoy shooting the messenger. They are armed and dangerous, hunting the very people who everyone needs to deliver the ground truth. They load their quivers with arrows targeted at the truth-tellers and are eager to advance their contemptible agendas at the expense of the honest and the innocent.

Some might say that to expect leaders to lead is to expect too much. Th is puts program and project managers in a precarious position. We expect projects and programs to be successful as a result of sound processes and best practices, even in spite of poor leadership. IT project leaders are expected to achieve success regardless of organizational and political obstacles. They are expected to deliver the ground truth even at their own personal peril.

We can’t make the mistake of assuming that those who operate in leadership positions actually do lead. We can’t assume that those who have oversight responsibility are effective and responsible leaders who are concerned about your best interest and the best interest of the organization.

Leaders who lack personal credibility impede progress despite processes and practices. Personal credibility is the seed that yields a harvest of competent leadership and oversight. Zig Ziglar said, “Your children pay more attention to what you do than what you say.” In the same way, team members expect their leaders’ actions to be consistent with their words. Do you trust a leader whose words and actions are inconsistent? Are you willing to follow a leader who has demonstrated a lack of credibility? The leader may follow established processes, such as developing project management plans, but a leader who is not credible lacks the ability to effectively and consistently motivate team members to follow his or her plans and directions. Leaders without personal credibility are unable to inspire others to trust and believe in who they are and what they do, and this lack of trust becomes a barrier between leaders and team members (Allgeier, 2009).

Leadership and personal credibility are processes, not destinations. They are processes that require continuous improvement, like tending a garden. They are personal struggles with outcomes that have interpersonal and organizational consequences. Success is not measured by how far you’ve come or by how many miles or kilometers you have left to go. Instead, success is measured by the quality of the harvest—by how effective you are at obtaining the benefits and the valued and required outcomes that projects and programs are designed to achieve.

As IT leaders, our challenge is to persevere in spite of these challenges, to resist imitating incompetent or corrupt leaders, and instead to behave credibly and ethically in the face of clear and present danger, to improve our leadership acumen and deliver the ground truth without wavering or flinching. Equipping ourselves to perform in this manner requires stalwart personal credibility fueled by self-leadership. Most geeks are not interested in such pursuits. Researchers have found that IT professionals scored below the norm for conscientiousness, which includes dependability, reliability, trustworthiness, and the inclination to adhere to company norms, rules, and values (Lounsbury et al., n.d.). But those who are—those bold enough to break from the geek culture in pursuit of leadership with credibility—can expect to increase their value to their organization and reap rewards for taking such risks.

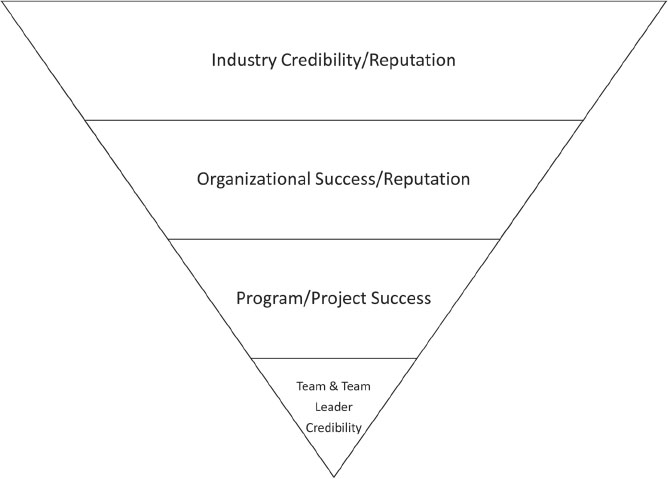

The personal credibility of IT leaders impacts the credibility of the organization and the credibility of the IT industry as a whole. As discussed earlier, the IT industry has a reputation for poor delivery of IT projects. Although several factors contribute to this issue, researchers have found that organizational and social factors, including leadership, have a profound impact (Thite, 1999). The credible IT geek leader can directly impact or influence these factors and, consequently, improve the success rate of IT projects and the credibility of the IT industry.

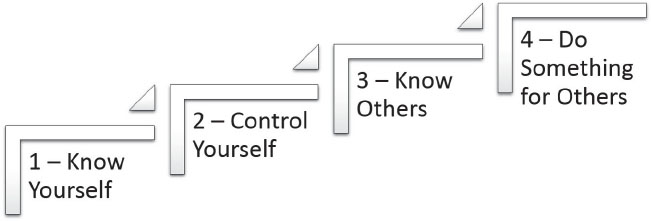

In this chapter, we begin with a case about a leader facing a personal credibility challenge. We then explore the concept of social styles, including the Driver, Expressive, Amiable, and Analytical styles. We examine the characters in the case to demonstrate how social styles can impact personal credibility. We then build on this knowledge of social styles as we discuss the Four Steps to Mindful Credibility: Know Yourself, Control Yourself, Know Others, and Do Something for Others. After the conclusion, there is a Leadership Assessment Questionnaire that can help you mindfully improve your personal credibility.

Let’s begin with a case about a manager with an incredible reputation. Th is story was inspired by actual events.

“Tony, you gave an excellent presentation this morning!” said Mr. Stamos.

“Thank you,” Tony replied. Tony was an IT project manager at DICOM Solutions (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine), and Mr. Stamos was his customer and the project sponsor.

Tony was sitting next to Mr. Stamos, having lunch. There were several customers at the table with them at the Annual Medical Imaging Conference, where Tony was a guest speaker. “Lunch is great today!” exclaimed Tony. “Th is hotel never disappoints,” replied Mr. Stamos.

“I need to talk to you about something,” Mr. Stamos whispered to Tony, leaning toward him. “What can I do for you?” Tony replied. They rose from the table and walked together toward the ballroom, talking privately.

“I saw on your website that you’re recruiting for a deputy project manager for our DICOM Data Repository project,” said Mr. Stamos.

“Yes sir,” said Tony. “Since we’re ramping up deployments, I need management help.”

“I may have just the guy for you—Craig Leonard,” said Mr. Stamos.

“He’s currently on your staff, correct?” Tony asked. “He’s participated on several conference calls. Is he looking to move on from your staff?”

“His contract with us ends next month, and as you know we’re facing a budget shortfall,” replied Mr. Stamos.

“I understand. Please send me his résumé and we’ll setup an interview,” Tony said, shaking hands with Mr. Stamos.

“You’ll have it tomorrow,” replied Mr. Stamos.

Craig interviewed for the position, and Tony hired him. Tony spent two weeks training Craig, introducing him to everyone and helping him get acclimated to the company. Coming from the customer organization, Craig already knew much about the program. After it seemed that Craig had caught on, Tony assigned him to manage customer deployments.

One Monday morning, Tony heard a commotion in the engineering area and went over to investigate.

“What’s wrong with you?” Jack screamed at Craig. Jack was a systems engineer on the deployment team. “How many times do I have to explain this to you?” he continued.

“What’s going on here?” asked Tony, walking over to Jack’s cubicle. “Craig told Mr. Jones at Walter Reed to order a switch for their data center,” said Jack, flinging his arms (Mr. Jones was the IT Director at Walter Reed). “We are not responsible for the network,” Jack continued. “We just tell the site how many Ethernet drops we need and they provide them. Now they expect us to configure the switch—that’s out of scope!”

“He did what? Is this true, Craig?” asked Tony. “Well …,” Craig replied with a shrug. “I’ll call Mr. Jones and clear this up,” Tony said. “Maybe they can return the gear.”

Jack followed Tony to his office. “One more thing,” Jack said, closing Tony’s door behind him. “On the kickoff conference call with Walter Reed yesterday, Craig was working from home while leading the call. Right in the middle of the call, he stopped everything, then came back and said ‘Sorry, I had to let the cable guy in.’”

“He did what? Ohhh—that’s not very professional,” Tony said.

“Why did you hire him again?” asked Jack. “He knows the program, and he came highly recommended from Mr. Stamos, our customer.” Tony said.

“Well, in my opinion, if he were any good, Stamos would have found a way to keep him,” Jack replied.

“Of course I’ll talk to him,” Tony said. “Whenever someone new joins a team, the team goes through the forming, storming, norming, and performing phases all over again. We’re storming right now, and that’s normal. But every ship doesn’t survive every storm. Let’s see how this goes.”

The next morning, Tony called Craig into his office. “Please, close the door and have a seat,” Tony said to Craig. Tony sat behind his desk, Craig sat at a table in Tony’s office.

“It seems you have had a rough start,” Tony said. “I’m sorry about the cable guy incident,” Craig said. “I don’t know what I was thinking.”

“You’ve been in this business a long time, Craig—longer than I have—and you come highly recommended by Mr. Stamos,” Tony began, looking Craig in the eye. “We have high expectations for you. We expect you to be technically competent, to be professional at all times, and to inspire confidence.”

Craig broke eye contact with Tony, looking down at the floor. “Our team members, like Jack, and our customers, Mr. Stamos and Mr. Jones, need to be able to trust you to deliver,” Tony continued sternly. “I need to be able to trust you to represent me and DICOM Solutions with credibility. Right now, I’m concerned. Your personal credibility is on the line. As a leader in this company, your personal credibility directly impacts the company’s credibility. You need to get your act together and you need to do it right now. Do you understand?”

“I do. I’ll try harder,” Craig replied, exhaling, never looking at Tony.

Two days later, Tony, Craig, and Jack were preparing for a conference call with Mr. Jones. The call was very important, because Craig had to review the deployment plan with Mr. Jones and the rest of the team to help them prepare for the deployment team’s visit to the site two weeks later.

“I didn’t see your draft deployment plan in my inbox this morning, Craig. Where is it?” Tony asked.

“I did not finish it,” Craig said, softly. “Why not?” Tony asked. “We need to provide it to the customer twenty-four hours before the conference call to give them time to review it and prepare questions. I thought you were working on it yesterday.”

“I got tired and I went home,” Craig replied, again with a soft voice.

“You did what?” Tony asked incredulously. “Argh! Send me what you have and I’ll finish it!” Tony yelled in frustration. “We don’t have time for this. We’re deploying three sites at a time, and the customer is depending on us to keep the schedule.”

Tony and Jack completed the plan in Tony’s office and sent it to Mr. Jones within minutes of the deadline. “Jack, you were right about Craig,” Tony said. Jack raised his hands, tilted his head to the side, and shrugged his shoulders.

As Jack left Tony’s office, Karen from Human Resources came in. “Good afternoon, Tony,” she greeted him.

“Hey Karen, I was just about to come see you about Craig,” Tony replied. “Interesting,” Karen said. “He’s the reason I’m here to see you. We completed Craig’s background check and found that he lied about having a degree. We just fired him.”

“He did what?” Tony exclaimed. “That guy’s lack of credibility is incredible!”

Each character in this story had his own way of interacting with others—his own social style. In the next section, let’s examine social styles and their relationship to personal credibility.

6.2 Social Styles for Personal Credibility

In Chapter 2, you learned about the Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) tool, which is useful for identifying behavioral preferences. MBTI helps you understand your own psychological tendencies for extraversion and introversion, sensing and intuition, thinking and feeling, and judging and perceiving. The social styles model is also a very useful tool for your IT geek leadership toolbox. Your awareness, adaptability, and versatility with personal styles can enable you to increase your interpersonal effectiveness and improve your personal credibility with team members, peers, senior leaders, customers, and other project stakeholders.

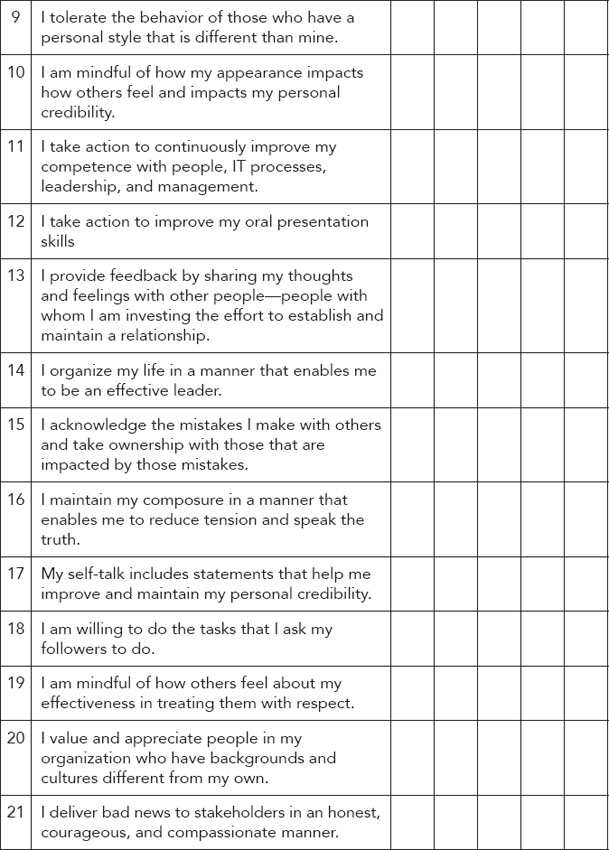

Psychologists David Merrill and Roger Reid published their social styles model in Personal Styles and Effective Performance in 1981 (Merrill and Reid, 1981). They defined four behavioral profiles: Driver, Expressive, Amiable, and Analytical:

• Driver. Behavior characterized by “telling.” Driver types “control” their feelings and are considered assertive and serious. They tell people what they think and require, and they usually do not display their feelings.

• Expressive. Behavior characterized by “telling.” Expressive types “emote,” showing their feelings, and are considered assertive.

• Amiable. Behavior characterized by “asking.” Amiable types “emote,” openly displaying their feelings, and are considered agreeable and cooperative.

• Analytical. Behavior characterized by “asking.” Analytical types “control” their feelings. They are inquisitive. Their nature is to gather data and study information.

These social style profiles, and their associated Myers Briggs Type Indicators, are shown in Figure 6-1.

All social style profiles are equal; one is not better or worse than another. Each has its own advantages and disadvantages, and each can be effective.

Like MBTI, we all have a dominant, preferred style. We have parts of each style within us, and we are capable of demonstrating those styles when necessary. However, our preferred style requires the least energy and stress and is therefore dominant.

The basic difference between MBTI and social styles is that social styles are based on the perception of others while MBTI is based on self-perception. Together, those two tools provide a more detailed and complete view of a person (Mulqueen, n.d.). As a leader, if you understand both, you can better adapt your behavior to make the person you are engaging with more comfortable around you, a concept Merrill and Reid refer to as versatility. The more versatile you are, the larger the audience of people who feel comfortable interacting with you, the better equipped you can be to handle conflict, the more people trust you, and the stronger is your personal credibility.

Figure 6-1 Four personal styles.

Our style does not define who we are, only our behavior patterns as perceived by others. Our styles do not define how we think or how we feel.

As we work together to achieve our shared vision, we still have different individual needs and goals. We communicate differently. We use time differently. Our style impacts how we make decisions and how we deal with conflict.

Let’s take a closer look at each of the social styles.

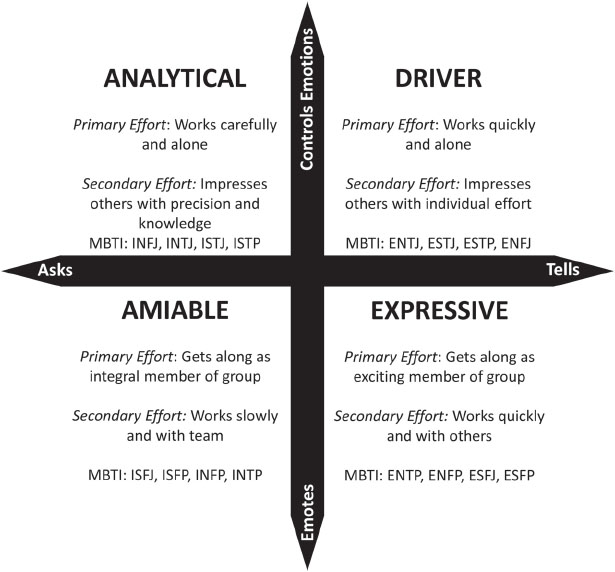

People with the Driver pattern of behavior are action oriented. They are task specialists who seem to know what they want and where they’re going. They don’t wait for someone else to initiate action. They are independent and may seem to work with other people only because they must, not because they enjoy it. Figure 6-2 describes the Driver style.

Figure 6-2 Driver style.

Those who display the Driver style prefer to respond quickly, and they prefer to be around others who do the same. They can be seen as impatient, getting things done in a hurry, even if rework is sometimes necessary. They take risks and decide quickly. They do not like being told what to do; instead, they would rather direct others (Merrill and Reid, 1981).

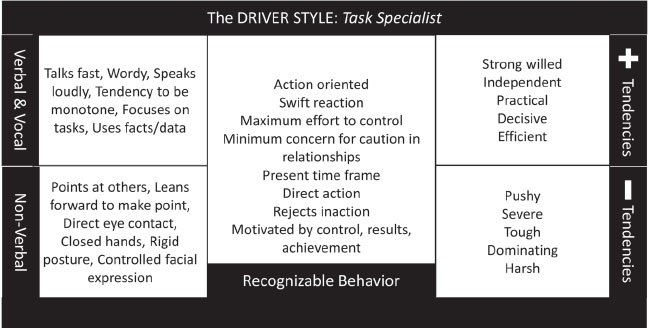

Expressive people place a high value on power and politics. They seem to prefer to be around people who support their dreams and goals instead of those who compete with them. They are ambitious, yet warm and approachable. Figure 6-3 describes the Expressive style.

People who portray an Expressive style focus on the future and are undisciplined in their use of time. They may appear fickle, changing their course of action when a new direction seems to be more exciting. They do not spend enough time on a subject to delve into the details, and they make decisions using their own intuition. Expressive people are willing to take risks that they feel can hasten achievement of their goals and desires. They are creative, and they rely on personal opinion more than on logic (Merrill and Reid, 1981).

Figure 6-3 Expressive style.

The Amiable person places a high value on relationships. They choose mutual understanding and respect over authority and force. They desire to be accepted. They make personal connections and pay attention to the personal motives and actions of others. Amiable people seek to bring joy and warmth to situations. Figure 6-4 describes the Amiable style.

Figure 6-4 Amiable style.

Amiable people enjoy socializing with others and may find it difficult to focus on work tasks. They enjoy taking time to share feelings and personal objectives. They appear to move slowly and to be undisciplined in their use of time because of their tendency to give social interactions a higher priority than work tasks.

Amiable people desire to have security and stability. They are slow to change, and they desire to have guarantees that the changes being planned will minimize risk and maximize promised benefits. They do not support changes that risk personal relationships. Amiable people place strong emphasis on their own personal opinions when considering change (Merrill and Reid, 1981).

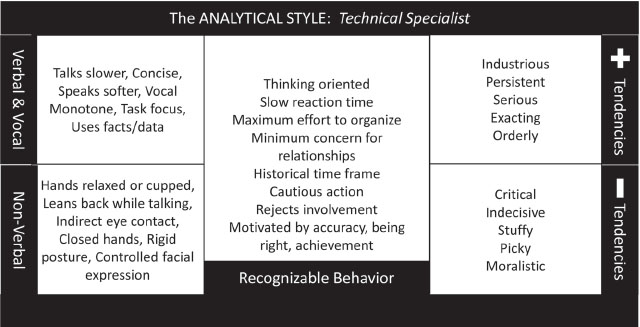

Analytical people think systematically and logically. They look for patterns with people and are reluctant to trust people—especially people with power—until they understand their patterns. Upon initial contact, they may seem to value logic and data over personal warmth and friendship, giving others the impression that they are cold and detached. They would rather get work done without involving other people if possible. They enjoy having the freedom to organize and can be cooperative with others once they feel organized. Figure 6-5 describes the Analytical style.

Analytical people like to take the time to analyze data, looking at historical patterns in order to understand the present and the future. They prefer a predictable, calm, and common sense approach to work, moving in a slow and deliberate manner. Analytical people are risk-averse and make decisions based on facts and data instead of on the opinions of others. They desire to be right and to make decisions that last (Merrill and Reid, 1981).

Figure 6-5 Analytical style.

All four styles—Driver, Expressive, Amiable, and Analytical—are part of the human experience and are necessary for a team to be effective. If one is only comfortable dealing with people with whom one shares a personal style, one may have a difficult time getting along with others. If one makes negative value judgments against people who have a different style, there can be tension within the work environment.

Let’s take a look at the characters from “The Incredible Craig” through the lens of social styles.

6.3 Analysis of “The Incredible Craig”

Craig displayed Analytical tendencies. Mr. Stamos thought he was a good analyst who understood the program, and he thought he would be an asset to Tony’s team. Having Craig, someone Mr. Stamos knew, on his vendor’s team gave Mr. Stamos an advantage. But the qualities that made Craig a good analyst did not help him become a successful leader. Craig was a man of few words. Although Analytical types are generally inquisitive, Craig did not feel comfortable enough to ask Jack questions about the details of their deployment methodology that he did not understand, resulting in his providing the client with inaccurate information. Craig was more concerned about his own desire to have cable television than about being respectful of his client’s and team members’ time. Craig took his time to produce the deployment plan deliverable. He preferred to work on tasks alone and not ask for help. He was not concerned about the client’s need to review the document before the conference call. He did not make the link between providing the document on time and his personal credibility. All of these behaviors are indicative of the Analytical social style. However, the lie Craig told about having a degree has nothing to do with social style. This behavior was unethical. It demonstrated a flaw in Craig’s values and signified that he could not be trusted.

Tony demonstrated Driver tendencies. He was good at “telling” and did not mind presenting information to clients. He had no problem “chewing out” Craig when he felt his behavior did not meet standards. He was not concerned about how Craig felt about his position or the tasks he was assigned. He was not concerned about why Craig felt tired and decided to go home. Tony was only concerned about outcomes. He reacted quickly when there were client issues. He took direct action to correct the deployment plan deliverable in order to meet the client’s deadline.

Neither Craig nor Tony displayed what Merrill and Reid refer to as versatility. Versatile people learn to control behavioral preferences when they create nonproductive tension in another person. Versatile people know how to communicate their words and intentions in a way that creates and maintains valuable interpersonal relationships. Versatile people interact with others in a way that makes them feel better about themselves. Others give versatile people endorsement, meaning people approve of their behavior and remain comfortable and non-defensive during encounters with them. No matter your social style, versatility is a skill that you can learn (Merrill and Reid, 1981).

Tony did not recognize Craig’s Analytical style. He did not understand that his expectations for Craig’s behavior were contrary to Craig’s style. He wanted Craig to be more like him. Since he was not aware either of his own style or of Craig’s style, he could not be versatile. He was unable to mentor Craig and help him learn to be versatile. While it is important to hold team members accountable, it is also necessary both to recognize where their style may cause them to be nonproductive and then to help them find ways to be effective in their roles using the strengths of their styles. Perhaps Tony could have facilitated collaboration between Jack and Craig in order to help Craig feel more comfortable about his relationship with Jack. Perhaps Tony could have involved Jack and Craig in team-building activities to help them understand each other. Perhaps he could have coached Craig to open up, helping him to understand that his inclination to work alone was not beneficial to the success of the team.

Versatile people monitor their behavior and adjust their actions to reduce tension in others, so that their actions do not interfere with their relationships with others. They share their feelings and thoughts about the messages they receive from others while also monitoring their own messages. They make an effort to understand what others are interested in and how they feel about situations. They seek to find common ground, asking good questions and providing good feedback (Merrill and Reid, 1981).

Craig did not engage in any of these versatile behaviors. As an Analytical person, he would have needed to exert some effort to gather the information he needed about the expectations for his leadership position. He would have had to operate outside of his comfort zone in order to collaborate with Tony and Jack to accomplish his assigned tasks. He would have had to demonstrate concern for how Tony and Jack felt about his performance, and he would have had to be willing to adapt his style in order to meet their expectations for his position.

The class I took on social styles included an exercise in which I had to identify my social style and deliver a presentation to the class on why I felt I identified with the style. “I am Analytical,” I said. “I love to work alone. One of my favorite activities is to go into work on a Saturday when no one is there and write code all day. I can spend 12 hours writing code, and the time seems to go by extremely fast. I would much rather interface with a computer than to interact with someone else.” The other people in the class with an IT background, who were also analytical, could relate. They saw me as dedicated and hardworking. The others could not understand how I could value a relationship with a computer over relationships with people. I had credibility with some of the class, but not with others, and that was fine with me. I was not concerned about what others thought of me. I was concerned about my own thoughts and actions, not about how my behavior might influence others.

In order to be successful in that business program, we all had to collaborate, working in small teams to complete class projects. We had to team up with people who were very different from us, who saw things from different perspectives.

Over time, I learned to appreciate the perspectives of others. I learned how our differences made us a stronger team. For example, I learned that if a team consists of members who are all Analytical types, the final result would most likely be an analytical one. When all four social styles are represented on a team, the team is in a position to analyze an opportunity or issue from various perspectives, providing a more complete result than if all of the team members had the same social style. Learning to appreciate—or at least tolerate—team members with a style that was not like mine took effort, but it turned out to be an investment with a high return. I learned to be versatile, and I learned that versatility leads to credibility.

Years after receiving this education in social styles, I was a program manager for a team deploying a large-scale hardware and software solution. One of the lead engineers on the team was very expressive. A conversation with him could be like the Seven Dwarfs Mine Train ride at Disney World: a strange, wild ride where you find yourself unsure of the direction you’re going and how it will end. The other engineers on the team found his style annoying, but I went out of my way to keep him talking because he was very bright and had ideas that helped us solve customer problems. Many evenings, I’d be at my desk catching up on email or working on a deliverable, and he would call me. I’d close my door, put him on speaker, and continue to work. The conversations proceeded something like this: “Uh huh,” I’d say, “Uh huh. Oh really? Oh, okay. Uh huh. Uh huh.” But then a gold nugget would appear. He would say something really important, and I’d say, “Wait—what was that?” Then I would stop multitasking and ask questions, focusing intently on the issue or opportunity he mentioned, digging deep to mine the vein of gold. Sometimes the conversation resulted in a new contract with a customer, other times it resulted in a more efficient way to perform deployments. If I had found this engineer annoying and avoided him, the way other Analytical team members did, the project, the company, and the customer would not have experienced the full value of this bright engineer, and we would have missed out on important opportunities.

It is easy to identify a person’s physical characteristics—whether he or she is short or tall, heavyset or thin, younger or older. A person’s physical traits may be advantageous or disadvantageous depending on the situation. Groups such as sports teams and singing groups that have physical objectives take advantage of the physical characteristics of their members to accomplish their goals. In basketball, for example, a shorter person may not be able to dunk but can use his or her shooting, dribbling, and passing ability to contribute to the team. A taller team member may not be able to handle the basketball well but could be an accurate shooter when close to the basket. In a men’s quartet, members have different voices: bass, baritone, first tenor, and second tenor. Individually, each may sing beautifully. Together, they can sing in harmony, producing a sound unique to their four blended voices, a sound that could make even the angels envious.

IT leaders need to recognize the mental characteristics and talents of their team members and stakeholders. If they understand who is amiable, who is analytical, who is a driver, and who is expressive, they can better assign team members to tasks that are compatible with their styles. IT leaders know when a task requires the team members to function outside of their comfort zones, and when they recognize this situation, they know to provide encouragement to help the team members feel comfortable and safe when performing their tasks. They know when the customer’s style may be considered annoying or irksome to a team member, and they can then help the team member to learn to tolerate this difference in style, making the customer feel comfortable interacting with the team member, a comfortable feeling that leads to clearer and more complete requirements than might be obtained otherwise. As with different positions on a sports team, or different voices in a singing group, individuals with different social styles can accomplish more together than any of them could accomplish by themselves.

Next, let’s explore Merrill and Reid’s four-step process for improving your versatility, a process that can help you mindfully improve your personal credibility and IT leadership competence.

David Gelles is a New York Times business reporter and the author of Mindful at Work. He provides the following great definition of being mindful: “Mindfulness is the ability to see what is going on inside our heads without getting carried away with it. It is the capacity to feel sensations—even painful ones—without letting them control us. Mindful means being aware of experiences, observing them without judgment, and responding from a place of clarity and compassion, rather than a place of fear, insecurity, or greed” (Gelles, 2015). This is exactly what we IT geeks need to exercise in order to achieve personal credibility. Because most of us IT geeks are introverts, we are very comfortable with living inside of our own heads. We think about what we say before we say it. We naturally try to connect the dots to solve problems.

Figure 6-6 Characteristics of mindful leaders.

Figure 6-6 depicts Gelles’ characteristics of mindful leaders, which he developed after interviewing and mentoring several mindful leaders.

Allgeier wrote, “People with high credibility are able to roll over things in their minds, consider different perspectives, and stay neutral in their own positions while they do this. They have chosen neutrality as their first course” (Allgeier, 2009). This mindful approach enables them to focus on an issue without being emotional. It allows them to obtain clarity when others are experiencing amygdala hijackings. It allows them to think creatively to find third alternative solutions to conflicts. Mindful leaders are self-aware and can therefore control their speech and behavior to ensure that their actions will have the intended short-term and long-term effects. They remain composed, enabling them to anticipate the reactions of others and counter their emotional reactions calmly and thoughtfully. Leaders who can behave like this, who take a mindful approach to work, will develop and maintain personal credibility because others—team members, senior leaders, and stakeholders—can trust them to be a positive influence in any situation.

Figure 6-7 shows Merrill and Reid’s four-step process for improving versatility, a process that can enable you to become a mindful leader.

Let’s explore each step in greater detail.

Figure 6-7 Four steps to mindful credibility.

Knowing yourself requires you to be mindful of the impression you make on others because of your behavior preferences. You need to be mindful of how these behavior preferences cause tension. Your appearance, your competence, your oral presentation skills, and your feedback skills can all be sources of tension for others (Merrill and Reid, 1981).

Your Appearance

An important area in which many IT geeks have blind spots is their appearance. A senior customer told me, “I need your systems administrators to be more aware of and concerned about their appearance when providing desk-side support. Many of our users are important people, highly educated, and are involved in critical programs and operations. They dress a certain way, and they are accustomed to being around people who are dressed a certain way. When one of your systems administrators show up looking like they slept in their clothes, these users feel uncomfortable.”

This sentiment is consistent with research. As discussed in Chapter 2, the Big Five study found that, in general, IT workers scored lower on “image management” than their peers in other occupations, meaning that they scored lower on the disposition to monitor, observe, regulate, and control the self-presentation and image they project during interactions with others (Lounsbury et al., n.d.). This presents a challenge for certain IT geeks’ personal credibility. I have known many, many IT geeks who are extremely capable, trustworthy, and dependable, but would rather color their hair purple than wear a tie or a business suit.

According to Susan Bixler, author of Professional Presence, “Whenever we walk into a room, our clothing, manners, and mannerisms are on display. Others assess our self-confidence and our ability to present ourselves based on about five seconds of information. Each of us has our own signature of professional presence—an indelible statement that we make the instant we step into a room—that should afford us an opportunity to connect immediately” (Bixler, 1992).

People judge us IT geeks immediately based on how we present and carry ourselves. Many people feel tension when they perceive that others are dressed in a way that is socially unacceptable or that is different from what they are used to. Dress is associated with attitude, and people with a perceived attitude of social indifference can make others feel uncomfortable (Merrill and Reid, 1981). In order to have personal credibility, we have to be mindful not just about how our appearance makes us feel, but about how it makes those around us feel and how it influences our ability to effectively interact with them.

Your Competence

In Chapter 4, Self-Leadership, we discussed that leaders need to take responsibility for continuously learning, gaining more and more knowledge and understanding of what is required to be a successful IT project leader. Those who do this can gain credibility with their team members, peers, senior leaders, and customer stakeholders. As depicted in Table 6-1, there is always more to learn about IT leadership.

Your personal credibility increases when you demonstrate a commitment to learning. No one expects you to know it all, but others do respect and respond to a passion for learning. Your résumé may make you look credible, but by your demonstrating passion toward improving your knowledge, others feel your credibility. One of the best compliments I have ever received was when my CEO said, “When I know he is involved, I just get the feeling that everything will be fine.”

Table 6-1 IT Project Leader Competence Areas

Technical Competence |

• Software Engineering • Software Development • Graphic Design • Network Engineering • Network and Systems Administration • Database Development • Database Administration |

Process Competence |

• Agile • Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL) • ISO 20000 • Capability Maturity Model Integration (CMMi) |

Leadership and Management Competence |

• Strategic Visioning • Program/Project Management • Human Resources Management • Communications • Environmental Awareness • Organizational Behavior |

Your Oral Presentation Skills

People constantly observe each other’s character, most often subconsciously (Allgeier, 2009). We form thoughts, impressions, and opinions, and then we reform them. We observe each other’s behavior, forming subliminal opinions of examined principles of right and wrong, honor and condemnation, and morality and corruption. Silently, as others observe us, the decisions we make about our behavior either strengthen our credibility or degrade it.

Have you ever gotten the sense that someone you know is not authentic? Perhaps they brag, exaggerating the truth about their accomplishments and credentials. Perhaps what they say is not in line with what they do. They give you the sense that they are not showing you their real selves. The image they portray of themselves seems to be out of sync with your perception of them.

People want to get to know the real you. They want to know that they are dealing with an authentic person, not someone pretending to be someone they are not. If you brag in an effort to make yourself seem more capable than you really are, or if you embellish the truth about yourself, you come across as phony. Others pick up cues from your nonverbal behavior and your voice inflections that give you away. They subconsciously try to determine if you are being real. People don’t trust others when they sense they are hiding something, when they sense that the person they are engaging with is not demonstrating openness and transparency.

Introverts by nature are not open. They do not express their thoughts like extroverts do. This can cause others to be suspicious of them, because it is difficult to detect what they are thinking. For many geeks who are introverts, this presents a challenge, because people have a difficult time getting a sense of who the geek really is.

As a versatile geek leader, it is important to learn to communicate in a way that makes others feel comfortable about you. Those we engage with expect IT leaders to master the basics: speaking clearly, enunciating properly, using correct grammar and diction, avoiding vulgar or sexist language and slang. Geeks also have to make an effort to not use jargon but to explain technical concepts in terms the listener understands. As stated in Chapter 2, meanings are in people, not in words, so find a way to use words to connect to the people you are addressing.

The key is to be yourself; do not pretend you have a style that is different from your natural style. If you are naturally introverted, let everyone know that. Let them know that you are aware that you could be perceived as aloof or self-absorbed, but the reality is that you like to think about things before discussing them and that you need time to digest information before responding. Whatever your style is, help the person you are engaging with engage with you by being transparent about how your mind works. This simple demonstration of transparency and authenticity can help others understand you, reduce suspicion, and build trust.

Perfection is neither possible nor required. It’s okay to show your warts, because doing so lets others know it’s okay for them to show theirs. Just be honest about your imperfections while demonstrating commitment to working hard to achieve the vision and goals of your project, to taking responsibility for leading your team effectively, and for improving your leadership ability along the way.

Use of Feedback

In Chapter 2, we explored the importance of feedback and dialogue in the communications process. Mastering this skill is important for IT geeks to improve their credibility with stakeholders. Through feedback, we send verbal and nonverbal signals to help others understand the message we are communicating and to assist others in communicating with us. Versatile leaders share their feelings and thoughts about the messages they receive and are mindful of others’ feelings about the messages they send. A versatile leader demonstrates personal credibility by using feedback and dialogue to mindfully reduce tensions in a conversation.

6.4.2 Step Two: Control Yourself

The next step of the Four-Step Process for Mindful Credibility is to control yourself. If you are mindful of your strengths and your weaknesses, such as those associated with your social style, you give yourself the opportunity to make the most of who you are, maximizing your strengths and minimizing your weaknesses. When you control yourself, you are mindful not only of others’ reactions to your behavioral preferences, but also of your tolerance level for the behavioral preferences of others (Merrill and Reid, 1981). This requires you to be open, transparent, and patient with others, slow to judge and slow to react.

The credible leader is organized, a characteristic of the Analytical social style. The credible leader’s transparency enables him or her to build trusted relationships and to face and overcome mistakes. Being patient, slow to judge, and slow to react requires composure. How can you obtain such skills? Gain them by using self-talk to shape your self-image and your behavior. Let’s examine these ideas a little more closely.

The Organized Leader

Credible leaders are organized, which enables them to behave in a proactive manner. They don’t have to “play catch up” because they make an effort to stay ahead. Others take notice of their organization and conclude that the leader is credible. Allgeier provides recommendations on how to get and stay organized in Table 6-2.

Table 6-2 Habits of Organized and Credible Leaders

Organization for Credibility |

• Avoid over-commitment. • Schedule daily “communication time.” • Keep time open between appointments. • Arrive early. • Keep your records in one place. • Keep your email organized. • Keep others informed if conditions change. |

Overcoming Mistakes

Teresa Allen wrote in Common Sense Service, “Conflict often occurs not because of grievous error, but as the result of two individuals who meet on that somewhat stressful road of life. Small mistakes on such days can put us on dangerous ground. If, however, we are able to honestly admit our human weaknesses and mistakes, most customers will forgive us and move forward in a positive direction” (Allen, 2010).

This is the difference between perceived success and perceived failure. Successful people generally have the credibility to admit their mistakes; unsuccessful people generally do not. Successful people work with their stakeholders—their customers, leadership, and teammates—to overcome mistakes before they become failures. Unsuccessful people generally do not acknowledge their own mistakes; instead they blame others, blame the environment, blame leadership, and even blame the customer, instead of admitting their own faults and culpability and moving forward to correct problems. Many have a scotoma—a blind spot—to their own flaws. Either that or they know about them but choose not to face them.

If you and your team make too many mistakes, you put your credibility at risk. Consider the process in Figure 6-8 to maintain or repair your credibility.

During a conversation with a group of customer representatives for a large contract, I was leading a review of our continual service improvement plans. I went over my assessment of our quality management system and what I believed we needed to improve in order to enhance customer service and quality delivery. During this session, one of our customers said, “Your predecessor pretended everything was perfect. She never acknowledged having any concerns or problems, even though we clearly were not happy with the service provided.”

Figure 6-8 Repairing and maintaining credibility.

“IT service management is like tending a garden,” I said. “As soon as you think you have removed all of the weeds, new ones pop up out of nowhere, so you just have to keep at it.” Everyone got it immediately. “I just rip out the garden and pour concrete,” one of them joked. “Yes, but then I get cracks in the concrete and weeds grow in the cracks,” another responded.

You can’t keep your garden free of weeds unless you first acknowledge that you have them. Pretending you are perfect diminishes your credibility and the credibility of your team and organization. “So pity the poor perfectionist,” wrote Dr. Adrian Furnham, professor of psychology at University College London and the Norwegian Business School. “They are driven by a fear of failure; a fear of making mistakes; and a fear of disapproval. They can easily self-destruct in a vicious cycle of their own making: 1) Set unreachable goals, 2) fail to reach them, 3) become depressed and lethargic, 4) have less energy and a deep sense of failure, 5) get lower self-esteem and high self-blame.” Th is is not the behavior of a leader—not a person people want to follow, and not a person with credibility. “There is nothing wrong with setting high standards,” Dr. Furnham continued, “but they need to be reachable with effort. It’s all about being okay; human not super-human; among the best, if not the best” (Furnham, 2014).

Once you have taken ownership for the responsibility of removing the weeds from your garden, for acknowledging and correcting your mistakes and those of your team, you are in a position to coordinate with your stakeholders to determine the best next action. All of these stakeholders need to hear from you about the issues you are facing and what you are doing to resolve them. None of them are perfect; they have weeds in their gardens too. Reasonable stakeholders understand that your garden will have weeds, that mistakes will be made, but they need to know that you are tending your garden, because they are impacted by the harvest your garden produces.

Not all stakeholders are reasonable or understanding about your mistakes. You have to manage your expectations concerning how they respond. Develop your corrective action plan as quickly as possible, making sure it is as sound as possible and that you have as much consensus as possible. This puts you in a defensible position against those who intend to politically harm you and your team members.

After you have addressed a mistake, share what you have learned with others in your environment. Many organizations have “lessons learned” databases and knowledge management systems for documenting and sharing experiences that will help others avoid mistakes in the future. Taking ownership of your mistakes and sharing how you resolved them allows you to leave the situation in the past. It enables you and your organization to grow and be more successful. Your leadership in this area can produce IT projects that are more successful—and an IT industry that is more credible.

Maintaining Composure

David Gelles provides a formula that can help you put yourself in a mindful state that leads to an expression of the ground truth. Figure 6-9 depicts Gelles’s advice for reacting mindfully to the situations you encounter as a leader, either at work or outside of work.

You cannot easily pick up subconscious cues from body language and tone of voice when you are talking. When you are listening deeply, focused, and open, you are more likely to obtain the information you need to make better decisions (Allgeier, 2008). You are more likely to avoid making mistakes that will lead to the failure of your IT project. Instead of engaging in heavy control talk, as described in the discussion of Talk Continuum in Chapter 3, engage in dialogue that enables you to obtain understanding of the ground truth and to collaboratively reach mutually beneficial solutions to problems.

Self-Talk to Improve Personal Credibility

Personal credibility is by definition personal. You cannot improve your personal credibility unless you take ownership of and responsibility for your attitude. You have to free yourself of excuses and of blaming others for your own credibility.

Figure 6-9 Reacting mindfully. [Adapted from: Gelles, D. (2015). Mindful Work. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.]

You can directly and effectively improve your attitude toward personal credibility with your self-talk. Your self-talk—what you say about and believe about yourself—shapes your self-image, your behavior, and how others see you. It impacts your ability to influence the situations you are involved in. Positive self-talk leads to positive influence, which leads to improved personal credibility and leadership, which leads to accomplishment of project goals and objectives.

The scripts in Table 6-2 were inspired by the writings of Dr. S. Helmstetter (Helmstetter, 1982). Put into practice, these self-talk recommendations can help you improve your personal credibility.

By seeing yourself as a credible person, and by performing in a manner that is consistent with how you see yourself, you become a role model for others. Meditating on your self-talk makes you mindful of your own behavior and attitudes, allows you to control them, and prevents them from controlling you. It allows you to focus on adapting your behavior and attitudes to influence your team and your project.

Being mindful concerning your personal credibility through self-talk can set you apart from those difficult and nasty people everyone wants to avoid. Just as debugging tools can assist in resolving intermittent bugs in software applications, self-talk is a tool that can assist in resolving intermittent bugs in your mental programming. Team members will see you not only as someone with position power, but as a role model—someone they want to emulate; and as a leader—someone they want to follow.

Table 6-2 Self-Talk for Leadership Credibility

What to say to yourself to improve your leadership credibility: |

• I take full responsibility for everything about me—even the thoughts that I think. I am in control of the vast resources of my own mind. • I alone am responsible for what I do and for what I tell myself about me. No one can share this responsibility with me. • I enjoy being responsible. It puts me in charge of being me, and that is a challenge that I enjoy. • I always meet the obligations that I accept. And I accept no obligations I cannot meet. • I am trustworthy. I can be counted on. I have accepted responsibility for myself, and I always live up to the responsibilities I accept. • I am versatile. I am aware of my style, I recognize others’ styles, and I adapt my style to make others more comfortable. • There is no “they” on whom I lay the blame, or with whom I share my personal responsibilities. • I have no need to make excuses and no one needs to carry my responsibilities for me. I gladly carry my own weight, and I carry it well. • Each day I acknowledge and accept responsibility not only for my own actions, but also for my emotions, my thoughts, and my attitudes. • I exercise self-control, staying organized, overcoming mistakes, and maintaining my composure. |

The next step of the Four-Steps to Mindful Credibility is to know others.

Mindfully building personal credibility requires looking outside of yourself and paying attention to others. If you pay attention, you can learn about the tension levels of the people you need to interact with in order to be successful. You can observe how they respond to your messages and what you can do to make their interaction with you more comfortable (Merrill and Reid, 1981).

If relationships are important for the success of your project, invest some time in observing your stakeholders to determine their social style. Pay attention to how their social style influences others in the environment. Use what you have learned in this chapter to minimize tensions when engaging with these key stakeholders, making them feel comfortable concerning their interactions with you and increasing your personal credibility.

This leads us to step four of the Four Steps to Mindful Credibility.

6.4.4 Step Four: Do Something for Others

Accommodating Preferences

After you have made the effort to know others, you are prepared to mindfully do something to accommodate their preferences (Merrill and Reid, 1981). For example, give Analytical types time and space to organize and prepare their thoughts concerning issues and solutions. Be a sounding board for Expressive types, allowing them to talk through issues to resolve problems. Change your attire so that you present an image that makes the person you are engaging with feel comfortable about engaging with you.

All of this may take significant effort on your part and may require you to sacrifice your comfort zone. You have to develop a tolerance for frustration. Only you can decide if this investment is worth it, if the relationship is important enough for the effort, and if the benefit outweighs the cost.

The more we practice this process, the more mindful versatility becomes a habit. We learn to adjust our behavior almost unconsciously to make others more comfortable (Merrill and Reid, 1981). To achieve this level, we have to be persistent, making the effort to gain experience and competence at being tolerant and accepting, steadily building our person credibility.

Credibility and Followers

As discussed in Chapter 5, the leaders’ behavior, whether credible or not, influences their followers’ behavior. Credible leaders are able to inspire others to trust them and believe in who they are and what they do (Allgeier, 2009). Bad leaders inspire poor follower behavior. “Bad leaders cultivate their in-groups with favors, and that makes it difficult for outsiders to identify bad leaders, or for followers to dislodge the leader from the position of power,” wrote Dr. Ronald Riggio, Professor of Leadership and Organizational Psychology and former Director of the Kravis Leadership Institute at Claremont McKenna College. “The in-group followers defend the leader and work to keep him or her in power. Bad leaders often exist because their followers allow them to remain” (Riggio, 2009). Like poor parents setting bad examples for their children, I have known senior leaders who scream and yell at their “in-group” project leaders, and then I witnessed those project leaders scream and yell at their team members. I am sure you have witnessed similar events.

Most people do not want to follow this type of leader. They want to follow a leader who cares and who is involved, a leader who is not afraid to get his or her hands dirty. Leaders who do not ask followers to do anything that they would not do themselves build credibility (Allgeier, 2009).

Credibility is not connected to position or status (Allgeier, 2009). Credible leaders not only rely on their position to influence followers—leaders who have proven themselves to be credible inspire confidence in those around them. By delivering time and time again, by being accountable, and by remaining competent, a leader earns the trust of team members, senior leaders, and stakeholders. This leader’s recommendations will be heard. By demonstrating respect and tolerance for the social styles of others, leaders earn the respect of their colleagues.

Respect for Others

No one has perfect personal credibility, but I find it especially hard to deal with those who are disingenuous, who intentionally present information out of context in order to attempt to gain an advantage and to further their own agenda. They knowingly revise history to suit their needs, exercising selective amnesia, remembering what they choose to remember and forgetting what they choose to forget. They paint misinformation the same color as the ground truth. They goad you into emotional reactions with personal attacks against you and your staff and take pleasure from their ability to use intimidation, agitation, and confusion to strengthen their position and weaken yours. These nasty people have no concern for ethics or personal accountability. They congregate together—the more senior ones hire those who are like them, and then they train the more junior ones to be like them.

In my first position as an IT manager, I was responsible for all of the information technology systems at a US Air Force facility. This was during the early 1990s, and the Air Force was just starting to deploy networks at all bases. The requirements grew faster than my staff, and we found ourselves working long hours to satisfy all of our customers. It was a labor of love, though, because it was all brand new and exciting. My boss saw everything we were doing and how we were trying to address all of the needs of the organization, from the lowest administrative assistant to the commander, every day. He came to the conclusion that I was “too nice.” He felt that I was naïve and that people were taking advantage of me, making it difficult for me to prioritize my work. I did not feel that way, but I took this senior leader’s advice to heart. Soon, an administrative assistant asked me for help, and then asked me to do a little more training than I normally provided, which would have taken more time. I don’t remember what I said in response, but I remember being mean. I don’t even remember if what I said to her was true, but I do remember that my response upset her. I remember that it damaged our relationship. I was true to my boss and his advice, but I was not true to myself. This incident lasted less than 20 minutes, but it has haunted me for more than 20 years. I did not behave like the real me, and I diminished my personal credibility. I made up my mind after that incident to always make an effort be true to myself regardless of the advice from senior leaders.

You can be more respectful than I was. You can be successful as an IT leader without disrespecting others, inflicting emotional pain, and damaging your credibility. When you disrespect others, you may suffer the punishment of social isolation (Reynolds, 2012). You don’t have to face the isolation that comes with this approach to life and work. All leaders have choices. Instead of choosing to be disingenuous, you can choose to be authentic. Instead of misrepresenting information, you can be honest and transparent. You can be ethical and credible, respecting others so that they will respect you. As a result, you will feel better about yourself and others will feel better about you.

Value Diversity

Respect for others includes respect for people in your organization with backgrounds and cultures different from your own. We live in a global, multicultural society in which people from different cultures and ethnicities frequently interact. In our IT projects, we are challenged to lead team members, follow senior leaders, and serve customers who are often of a different race, gender, age, or sexual orientation than our own.

Ethnocentrism is the tendency for people to put their own ethnic, racial, or cultural group at the center of their observation of the world. The ethnocentric person believes his or her own culture is superior to that of others. Ethnocentrism is a universal tendency that may include the failure to recognize the unique perspectives of others (Northouse, 2007).

Prejudice, closely related to ethnocentrism, is largely a fixed belief, attitude, or emotion a person holds toward another person or group that is based on faulty or unsubstantiated data. Prejudicial beliefs are generalizations that are resistant to change. These beliefs are judgments based on previous decisions or experiences with other people or groups (Northouse, 2007).

While we all hold ethnocentric attitudes and prejudices to some degree, these tendencies negatively impact our personal credibility and our ability to be effective leaders. A leader needs to recognize his or her own ethnocentrism and to understand and somewhat tolerate ethnocentrism in others. Leaders must balance the confidence they have in their own ways of doing things with recognizing that the ways of other cultures are also legitimate. Leaders must fight their personal prejudices and address the prejudices of their followers. They must address prejudices that followers have toward each other, toward stakeholders, and even toward the leader (Northouse, 2007).

Prejudice is sometime subtle. I was once one of two African-American project managers at an IT consulting firm. I would meet with my boss, a vice president, once a week to discuss my projects. One week, he told me about a situation with another client. My boss, the project manager for that client, and the company CEO had to visit the client to resolve a critical issue. After the meeting, my boss met privately with the CEO. “That was a close call,” my boss said, “but everything seemed to work out fine.” The CEO replied, “Yes it did, but the next project manager to fail will be Byron.”

My boss told me he was astonished by the CEO’s statement. He said my name had never come up in any discussion, and that the project that failed had absolutely nothing to do with me. He said he was aware of the status of all of my projects, and there were no issues. “The only reason that he would make that statement is because you are African-American,” my boss said. I felt hurt and threatened, but not surprised. I had been told earlier that the senior leadership, including the CEO, had made racist remarks about a female African-American consultant the board had sent over for an audit.

I respected my boss for telling me the ground truth, but I lost all respect for corporate leadership. While I did not experience overt racism, corporate leadership created an atmosphere conducive to racial intolerance. I realized that I was not going to be promoted within that company. Even worse, I realized I was not secure in the position I held. By the grace of God, I was recruited for a program manager position in another company not long after that situation occurred.

Just as a leader needs to be tolerant of those with different social styles, he or she needs to be tolerant of those with different ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Leaders need to be mindfully honest with themselves about their own ethnocentric or prejuidicial attitudes and those of their team. The leader must make an effort to treat everyone with respect regardless of their cultural backgrounds. Others will endorse the leader who treats everyone equally, with compassion and empathy, as a versatile person, someone with personal credibility.

Delivering Bad News

Senior leaders, team members, and customers need to hear the ground truth from someone that they trust. However, delivering bad news can be extremely stressful. Many messengers have been shot, and some have never recovered from their wounds. Many executives who are poor leaders have inflected wounds on their IT managers when they attempted to deliver unfavorable information—information that the executives in fact needed in order to make the right decisions.

Where can the IT professional turn to learn how to deliver bad news? How about the medical profession? Every day physicians have to deliver bad news to patients. No one wants to hear that they have an incurable disease or that they are terminally ill. Yet, facing the stress of delivering this distressing information is one of the physician’s occupational obligations.

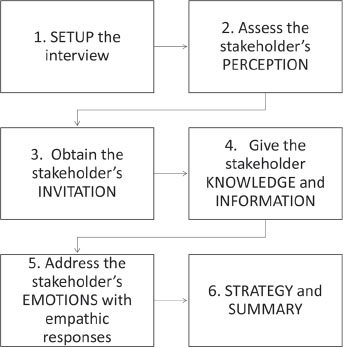

Physicians use a process with the acronym “SPIKES” to deliver bad news to patients respectfully and compassionately (Baile et al., 2000). Bad news concerning IT projects is rarely a life-and-death matter, so if SPIKES works for physicians, it can work for IT leaders. The SPIKES process is depicted in Figure 6-10.

Let’s explore some key activities in this process.

1. SET UP the Interview:

• Mentally rehearse the conversation.

• Expect to have negative feelings and to feel frustrated or responsible.

• Arrange for privacy.

• If possible, ensure that everyone is seated and in a relaxed position.

• Establish rapport by making eye contact.

• Choose a time when you will not be interrupted.

2. Assess the Stakeholder’s PERCEPTION:

• “Before you tell, ask.” Ask relevant questions to understand the stakeholder’s perception of the situation.

• Correct misinformation and misunderstandings.

• Address unrealistic expectations.

3. Obtain the Stakeholder’s INVITATION:

• Determine how much detail the stakeholder needs about the situation.

• If possible and relevant, let the stakeholder know that more details are available in the future.

4. Give the Stakeholder KNOWLEDGE and INFORMATION:

• Warn the stakeholder that you are about to deliver bad news: “Unfortunately, I have some bad news for you,” or “I’m sorry to tell you that …”.

• Speak in terms of the stakeholder’s vocabulary, in a way that you know he or she will understand. Avoid using unfamiliar jargon.

• Do not be excessively blunt.

• Give the information in small chunks.

5. Address the Stakeholder’s EMOTIONS with Empathetic Responses:

• Understand that this is a very difficult part of the conversation.

• Observe and identify the stakeholder’s emotion, naming it to yourself.

• Try to understand the reason for the emotion.

• Give the stakeholder time to express his or her feelings.

• Connect with the stakeholder’s feelings: “I wish we did not have to face this situation.”

• Continue the dialogue until the emotions clear.

6. STRATEGY and SUMMARY:

• Check the stakeholder’s understanding of the situation.

• Explore options to address the issue going forward.

Figure 6-10 SPIKES process for delivering bad news. [Data derived from Baile et al. (2000). "SPIKES—A Six-Step Protocol for Delivering Bad News: Application to the Patient with Cancer." The Oncologist, 5(4): 302–311.]

The SPIKES process helps you mindfully deliver bad news in a compassionate manner, providing the stakeholder with information he or she needs but does not want to hear while allowing you to keep your credibility intact. I have used this process during personnel layoffs, both for informing team members of the decision to lay them off and for explaining the situation to the remaining workforce. I made every effort to deliver the bad news mindfully and compassionately; however, not one of these conversations was easy or stress-free.

There is a relationship between your personal credibility and your leadership, your leadership and the success of your project, the success of your project and the success of your organization, and the success of your organization and the state of the IT industry. Figure 6-11 shows this relationship as an inverted pyramid.

Everyone in the information technology industry plays a role that impacts the industry’s reputation. Personally, I want our industry to have a solid reputation. I want the public to have the same confidence that an IT project or program will be successful as they have that a highway construction program will be successful. In the same way that I don’t want to be associated with a failed project, I don’t want to be associated with an industry with a reputation for failure.

By accepting the responsibility for building and maintaining their personal credibility, IT geek leaders take an important step toward making this dream a reality. As a credible IT geek leader, you can become important to your organization. You can make your organization more valuable, and your leadership will place a higher value on you, putting you in a position to receive promotions and awards.

Figure 6-11 Credibility and the industry.

In Chapter 7, we explore leadership within the context of a quality management system that integrates leadership into standard IT project management practices. You will learn how to plan, implement, and maintain an effective leadership system that can enable you to deliver projects that meet stakeholder requirements.

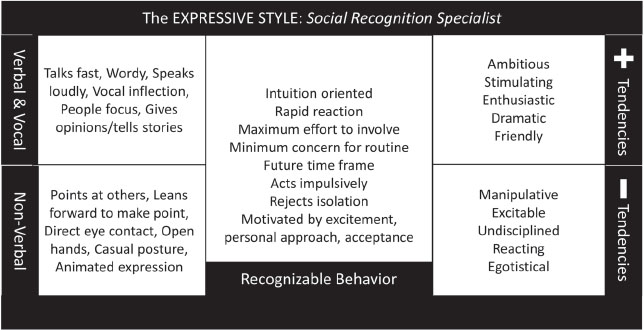

Leadership Assessment Questionnaire

The statements in this questionnaire are designed to help you examine your personal credibility. This examination can help you identify and develop an action plan to improve your personal credibility.

Use the following key for this assessment: