Emotionally Intelligent Communications

Because most IT professionals are introverts, IT geek communication requires energy and concentration to convert thoughts into words. Communication is also an emotional process. People not only hear what is said and interpret body language, they also associate feelings to the conversation, feelings that impact their understanding. Communicating with emotional intelligence means connecting with people at a level that enables transition of meaning and understanding from one person to another person or group of people. Dr. Sanford Berman wrote in Words, Meanings, and People (Berman, 2001) that meanings are in people, not in words. The goal is to ensure that the meaning the sender intends for the message is the meaning the receiver interprets from the message. Because words have different connotations to different people, because people interpret nonverbal signals differently, and because the political din in organizations is deafening, the communications process is plagued by complexity and errors.

3.1 The Importance of Effective Communication

Research has shown that project managers spend 90% of their time communicating (Rajkumar and KP, 2010). IT project managers trying to find success in complex environments that are prone to failure have their work cut out for them. It is like trying to climb Mount Everest during a blizzard while being pursued by a snow leopard. For IT professionals that are introverts, the communication process needs to proceed as efficiently and effectively as possible, without wasting precious energy. Efficient communication enables IT professionals to channel their energy toward delivering solutions that meet business objectives and that satisfy customers.

One morning I was working in my office when I heard my best project manager and my new project manager arguing. They were screaming at each other as they walked toward my office to escalate their situation to me. I was very concerned because I needed the two of them to work closely together on several critical projects and because they were distracting others in the office. We were under pressure to perform and stress levels were high.

The body language of the two PMs was contentious. I was afraid that one PM would strike the other. I knew that my body language would influence their behavior. I needed them to focus on our critical project because their bickering was not contributing to our success. If they did not work together, the project schedule would slip, we would overrun the budget, and the quality of delivery would suffer.

My initial impulse was to raise my voice and berate them for creating a scene in the office. However, I understood that I had to remain calm in order to influence them, to calm them down so that we could sort out the matter. I ushered them into my office, closed the door, and told them to sit down. No matter how loud they were, I kept my voice calm and low. When they were talking over each other, I’d raise my hand, palms out, facing them, signifying “stop,” to give the one that was explaining his or her frustration the opportunity to finish their thought. After a few minutes of this, the PMs were able to calmly explain their positions.

The new PM felt frustrated and disrespected. She felt the seasoned PM was not sharing information with her because of her gender. The experienced PM denied the allegation.

At the end of the conversation, they were both calm. It was a misunderstanding that could be cleared up if they engaged in dialogue. The experienced PM agreed to work harder at sharing information in order to get the new PM up to speed on the project. There was an obvious need for the two PMs to learn to trust and communicate with each other more effectively. I knew I needed to keep a close eye on them and to work with them to facilitate establishing an effective working relationship.

The walls of my office were paper-thin. A coworker in the next office said to me later, “I have no idea how you stayed calm during that situation.”

In order to understand how to lead people through complexity, you need to understand how they think. If you have a basic understanding of how the human mind works and why people behave the way they do, you can more effectively communicate with them and influence their behavior. IT projects are generally very complex and include a significant amount of uncertainty. Communication at a person-to-person level facilitates understanding and combats complexity. This type of communication enables team leaders, team members, and stakeholders to understand each other. If a team understands the problems they face and can work together with cohesion, they can find solutions, even in complex environments. A leader is responsible for bridging gaps when the individuals involved in a project do not understand each other and do not understand the problems they are tasked to solve. This is especially true when team members do not understand each other, a team does not understand its customer, or the customer does not understand the team. By understanding the basics of how people think, an IT project leader is better equipped to facilitate communication and understanding, reducing complexity and uncertainty and increasing the probability of project success.

Because the human mind is considered the most complicated structure in the universe, emotionally intelligent communication is complex. You, the intelligent IT geek, are more than capable of handling this complexity.

My goal for this chapter is to introduce you to the workings of the mind, as reported in recent psychology and neuroscience publications, and to relate this information to the communication process. At the end of this chapter, you will have a basic understanding of how the mind functions during the communication process. This understanding can enable you to tailor your communications in a manner that provides the greatest efficacy, enhancing your ability to influence people and situations—a core leadership purpose.

Let’s start our journey by reviewing a use case called “Missed Signals.” This use case is based on actual events that I have experienced. The characters in the story are based on real people. I am playing the role of Tony, the program manager. I will refer to this use case at various points throughout this book.

“You people are just lazy!” Karen screamed. “I don’t understand why it is so hard for you to correctly complete the inventory sheets! This data is useless! You need to go back and get the correct data! Our customer is furious about the inaccuracies in our daily reports!” Karen had just taken over a troubled team working on a high-visibility workstation migration project. Her face was flushed red when she spoke. Everyone could sense that her heart was racing.

Mark, a team member, sat quietly in his chair, wringing his hands beneath the table. Then he decided that he had heard enough. He was offended. His defense mechanism was activated, and he tuned Karen out.

Karen didn’t know that Mark had been passively looking for a new job. After Karen’s rant, a lashing similar to one he had endured from the previous project lead just a week before, he called a recruiter during his lunch break and set up an interview.

Three weeks later, Mark was attending an exit interview with Sandra in Human Resources (HR). “That Karen is a piece of work,” he said. “I hate how she talks to us. I know it’s an important project, and I know there are issues, but she makes me hate coming to work.”

Sandra and Tony, the program manager, had a monthly meeting to discuss HR issues on the program. “We received a complaint during an exit interview about Karen’s communication style,” Sandra explained, leaning forward, steepling her hands on the table, her fingertips touching. “She comes across as overbearing,” she continued.

“I’ve spoken to her about this,” Tony replied, leaning back in his chair, hand on his chin. “I’ve explained to her and to the other leads on the project that this type of behavior can be perceived by the people on the team as hostile, perhaps giving them grounds for a ‘hostile work environment’ claim. They all committed to toning it down. But please understand: our customer is getting yelled at by his superiors, and when he faces pressure, he applies pressure to the team. There’s not much we can do about that,” he said while raising his hands. “We do what we can to provide encouragement, but at the end of the day, it’s a high-pressure project in a high-pressure environment. On top of that, I asked one of the technical leads why we had so much trouble gathering the required inventory information, and the response was ‘they just don’t want to do it.’ These are the same people that are dogging Karen during their exit interviews. I find it hard to give them any credibility. Lastly, after Karen counseled the team, their performance did improve.”

“I understand,” Sandra said, “but no matter what the leads are feeling, they do not have an excuse to berate the employees so harshly.” “That’s why I asked for help with leadership and supervisory training earlier this year,” Tony replied. “Our techs are trained and experienced in information technology; they’re experts in Microsoft Windows 7, MS Active Directory, TCP/IP, and the like. They are leads because of how well they deploy and maintain technology. Karen has over 20 years of experience in this area, as do I. But Karen never received training on how to deal with difficult people, both difficult customers and difficult employees. She’s never had any type of leadership training.”

“You’re right,” Sandra said. “This is an issue we face across the company—across the industry, really. But we’re concerned that the company will not be in a position to defend itself if this situation ends up in court,” Sandra continued, crossing her legs so that her knees formed a barrier between her and Tony. “I have a couple of online communications courses I’d like for Karen to attend. I will send them to you so that you can instruct her to take them. This will show that the company has recognized the problem and that we’re taking action to prevent this situation from occurring in the future.”

“I’m all for training,” Tony replied, “but I think it would be better if someone from HR spoke with Karen first.” “Speak to her about what?” Sandra asked in a higher tone of voice. “About the complaint,” Tony replied. “Doesn’t she have a right to know who made the accusations, and doesn’t she have a right to respond?” “That’s not necessary,” Sandra explained. “Our only requirement is for Karen to take the courses.”

The next day Tony spoke to Karen about his conversation with HR. “I forwarded you an email from Sandra in HR,” Tony told Karen. “Apparently, one of the technicians who left the project recently said something about your communication style during an exit interview. I’m not privy to the details of the exit interview, but HR needs you to take a couple of online communications courses, the courses I sent you in the email. The courses only take about an hour apiece to complete, and you have 30 days to complete the courses. How do you feel about this?”

“I don’t understand. What did I do wrong?” replied Karen, holding up her hands below shoulder level, palms facing up. “Apparently, one of the techs was offended by how you spoke to him about the inventory data issue. HR was not forthcoming with the details,” Tony replied.

“But why didn’t they reach out to me to discuss this?” asked Karen. “I don’t know,” said Tony, shaking his head. “Look,” Tony continued, lowering his voice to almost a whisper, “if you just take the courses, which are good training for you anyway, all of this will blow over, it will just go away.” “Ok, Tony,” Karen said, as she turned on her high heels and walked away. “Whatever you need.”

A couple of weeks later, Karen knocked on Tony’s door. “Come in,” he said. “Do you have a minute?” replied Karen. “Absolutely. What can I do for you?” Karen entered the office, closed the door behind her, and sat down in a chair in front of Tony’s desk. She then placed a piece of paper on the desk and slid it to him. “I’m resigning,” she said. “This is my two-week notice.” Tony leaned back in his chair, threw back his head, and put his hands over his eyes. “Oh no!” he said. “Why? What happened? We just gave you a raise!” “I know, I know,” Karen said, leaning toward Tony, “and you transferred me from my position in service operations to be the special project lead. And I do appreciate that. But the communications course was the last straw. There were several incidents that occurred before you got here. I don’t like the way some people have been treated around here. I know that you’ve tried to fix some things since you’ve been here, but the fact that HR made me take that training without talking to me about what happened pisses me off. I never got the chance tell my side of the story, and now that incident is in my file. That was the last straw.” “Is there anything I can do?” asked Tony, sounding desperate. “I don’t have a problem working for you or this project,” replied Karen, “I just don’t want to work for this company.”

There were many different emotions expressed in this use case. We are going to analyze this use case later in this chapter to help you understand it within the context of emotionally intelligent communications. Let’s begin with a basic understanding of how the brain operates.

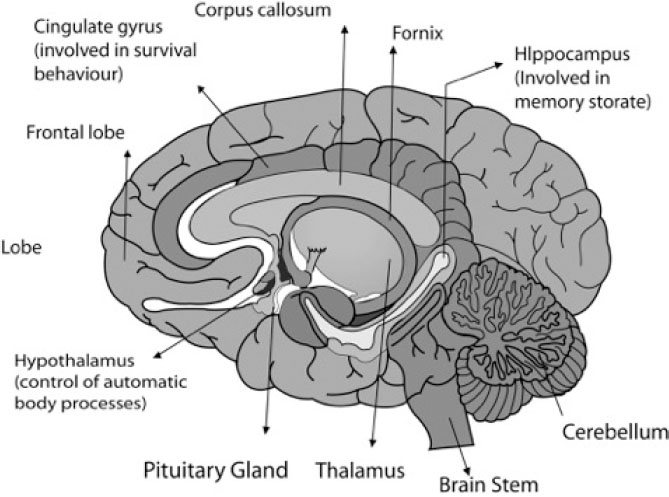

Many scientists feel that the human brain is the most complex creation in the universe. I cannot explain all of these complexities. However, in order to understand emotional intelligence, you need to understand the basics of the human brain, the source of emotions and intelligence. Our discussion of brain functions begins with the reptilian brain, then progresses to the limbic system, and ends with the cortex. Figure 3-1 illustrates the basic anatomy of the human brain.

The oldest part of the brain is known as the reptilian brain, consisting of the brain stem and the cerebellum. The reptilian brain controls heart beat, breathing, swallowing, body temperature, digestion, and other functions necessary for survival. Although reliable, the reptilian brain is considered to be rigid and compulsive. It controls our flight-or-fight response and urges such as hunger and sex (Chopra and Tanzi, 2012; The Evolutionary Layers of the Human Brain, n.d.).

Figure 3-1 Anatomy of the brain. © Gnanamdesigns | Dreamstime.com—Brain Photo. Used with permission from Dreamstime.com.

After the reptilian brain was developed, the limbic brain evolved. This type of brain emerged first in animals. The limbic system consists of three components. The first is the amygdala, which is associated with events and emotions such as fear, anger, indignation, rage, and pity. Another key component of the limbic system is the hippocampus, which processes information from the present into long-term memory and assists in recalling those memories. The last component of the limbic system is the hypothalamus, which controls automatic body processes. The limbic system is the source of our value judgments, which impact our behavior, judgments that are made unconsciously (Fogel, 2014; The Evolutionary Layers of the Human Brain, n.d.).

The region of the brain that was developed most recently is the neocortex, which represents the majority of the cerebral cortex. This region of the brain has between 10 and 14 billion tightly packed neurons. The neocortex is divided into four lobes that process sensor information: frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital. Because it is the outermost layer that surrounds the brain, it gives the brain its wrinkly appearance. It is in the neocortex that higher thought takes place, including decision making, learning, logic, language, and planning. It receives and processes sensory information and controls voluntary movement. These higher thought functions allow us to be self-aware; to observe and reflect on our own thinking; to have free will, choice, and self-control; and to develop human cultures (Chopra and Tanzi, 2012; Fogel, 2014; The Evolutionary Layers of the Human Brain, n.d.; Swenson, 2006).

IT project leadership takes place in the neocortex, which allows us to logically plan, make decisions, and communicate with others. This conscious activity is influenced by unconscious activity processed in the limbic system, resulting in emotions and body language that impact communication. Our reptilian brain causes automatic reactions to events we sense in the outside world and the emotions we feel. For example, fear and anger may result in a faster heartbeat.

Now that we understand the basic brain operations, let’s explore four phases of the brain: Instinctive, Emotional, Intellectual, and Intuitive. A brief description of each phase is provided in Table 3-1.

With respect to evolution, instincts developed in our reptilian brain, the part of the brain that existed before emotions. The anxiety we feel partly stems from the instinctive brain. It sends signals of fear, and it cannot tell the difference between fear of public speaking and fear of an approaching snow leopard. We struggle to manage our impulses—to distinguish between true dangers and those that are exacerbated by our instinctive brain. We control the impulses we can and respond to those we can’t. This is the source of courage—to feel the impulse of fear, assess it, and take rational action despite it. Our instincts are part of who we are—part of the human condition. We need to approach our fear and anger patiently, controlling them and not allowing them to control us. There may be times when it is appropriate to express our fear and anger freely, but that should be a conscious decision, not a mindless reaction.

Table 3-1 Four Phases of the Brain

Instinctive Phase | Intellectual Phase |

Brain Area: Reptilian | Brain Area: Neocortex |

Instincts are a necessary part of who we are. | Intellectual thought is blended with emotion and instinct. |

Mindfully manage fear and anger. | Intellect develops rational responses to fears and desires. |

Be aware of fear and desire to keep them in balance; acknowledge feelings of guilt. | Intellectual responses should be ethical. |

Mindfully live in the gap between impulse and response. | |

Emotional Phase | Intuitive Phase |

Brain Area: Limbic | Brain Area: Neocortex |

Letting feelings come and go helps us understand ourselves and the world. | You can trust your intuition and “feel” your way through life. |

Understanding our own emotions enables us to respond mindfully rather than to react mindlessly. | Snap judgments are accurate and are faster than reasoning. |

Reasoning is used to justify intuition. |

Data derived from Chopra, D. and Tanzi, R. (2012). Super Brain. New York: Random House Publishing.

When faced with situations that challenge our sense of self, our understanding of the world and our place in it, we feel psychologically threatened. At an unconscious level, our cognitive unconscious (subconscious) lets us know in subtle ways that danger is present, regardless of whether it is physical danger or psychological danger. The instinctual signals, in the form of “gut feelings” and stress indicators, impact our decisions in the cognitive unconscious mind, before our conscious mind contemplates the decision. It is constantly analyzing patterns and comparing what it perceives with patterns stored in memory (Kehoe, 2011).

As long as situations are positive, the processes work well. But if the situation quickly changes from positive to negative, the cognitive unconscious can give off signals that are not in line with the actual situation. We put our words (which are minor representations of ourselves) out there, and if someone disagrees with us and it comes as a surprise, or if it comes in a way that seems to diminish our sense of who we are, the cognitive unconscious reads this as a threat. A threat is a threat to your cognitive unconscious, whether it is a psychological threat to self-esteem or a physical threat to your body. This takes place very, very quickly, before your conscious mind even knows what is going on. Changes in the facial expressions and mannerisms of our critics signal our cognitive unconscious and cause reactions in our bodies before their words reach our ears. Our heart beats faster, increasing the sweat on our palms, raising the hair on our forearms, tightening our neck and throat muscles, forcing blood from our gut to our limbs, all in an effort to signal us that the threat is about to manifest. It is an “amygdala hijack” that invokes a fight-or-flight response—a sudden emotion that comes very quickly and that leads to irrational or inappropriate actions or talk. This system, which is intended to protect us from threats, actually makes the situation worse by matching patterns erroneously and causing us to respond from the place where we learned our judgments instead of from the present moment. At the same time, the person we are talking to is reading our automatic reactions and is invoking a cognitive unconscious response to them. This cycle feeds itself, and communications spiral out of control (Kehoe, 2011).

As leaders we must train our conscious minds to recognize when this process is playing out and allow our conscious selves to slow down the process and be mindful of the current situation, to react to the here and now and not to the situation that provoked the emotional response when the “threat” was detected. We have to live in the gap between the stimulus and the response. Not only must we control our own reactions, but we must help those with whom we are communicating—our communication partners—do the same.

Instincts and emotions are tightly aligned. Emotions allow us to name the feelings we experience as a result of our stimulated instincts. Whether we are sexually aroused or frightened to the point where we want to fight or flee, the alignment between instinct and emotions provokes a mindless reaction.

Somatic markers are the biochemical changes deep within the mind-body. These changes, known as “somatic” or “body” states, impact posture, blood flow, heart rate, muscle contractions, hormones, and other bodily conditions. For example, when someone is happy, the associated bodily change may be a smile as well as a change in breathing pattern.

These changes in somatic markers may be pleasant or unpleasant, and they may impact a person’s attitude concerning the event or object that influenced the change. For example, if someone experiences their “stomach being tied up in knots” before speaking in public, the mere thought of public speaking may elicit a similar experience, albeit to a lesser extent (Moss, 2011).

When we become aware of somatic markers, we name them, and they become our feelings. Becoming aware of our feelings, naming them, and describing them in a way that is accurate and useful to ourselves and to others is a fundamental component of effective communications (Kehoe, 2011).

The cognitive unconscious mind, the automatic function that operates out of our limbic system, supports rational decision making in our conscious, intellectual mind. It assesses the biochemical patterns in our minds to sense our environment before our conscious mind can do so. The cognitive unconscious enables us to quickly recall the meaning of words and to detect subtle nonverbal signals. However, the more automatic our thinking, the less effort is required, and the more prone we are to mistakes. It is easier, requires less energy, to react than to think; to say what comes to mind first instead of to carefully choose our words (Kehoe, 2011).

Basic Emotions

Hurtful speech damages relationships because it causes emotional pain. The listener’s brain recalls similar hurtful experiences stored in the limbic system and again experiences the psychic pain associated with that memory. The speaker may apologize, and may try to take back what was said, but the impression from the offensive speech lingers and impacts how the listener interacts with the speaker for the rest of their lives. As the great poet Maya Angelou said, “I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel” (Shriver, 2014).

Table 3-2 describes views on a few basic emotions from Dr. Robert C. Solomon, a philosophy professor from the University of Texas at Austin.

Resentment is a particularly important emotion for IT leaders to understand. I have found that after resentment builds up within employees over time, they seek their vengeance by resigning. A colleague of mine was resentful because he felt that his supervisor did not respect his skills and experience. He became very irritated by his supervisor’s habit of second-guessing all of the consultation he provided. His team was at a critical juncture in their project. He shared with me that he found another position and that he could not wait to leave his team so that they would be short of resources and facing failure.

LeRoy Ward writes at ProjectConnections.com, “While there’s a long list of risks any organization faces when starting an IT project, certainly one of the biggest risks has to be the potential that the team members you start with might not be the same ones you end with; and changing team members in the middle of a critical project can be very disruptive. If you lose a key technical person, or one who’s doing a great job at client relationship management, this could pose serious obstacles to project success” (Ward 2014). According to Baseline Magazine, 81% of IT professionals surveyed in 2014 said they were open to new job opportunities. This was true even for happily employed IT geeks that were in the job market. Taking actions to prevent resentment, such as maintaining a dialogue with your team members, treating everyone fairly and respectfully, standing up on your team members’ behalf, and involving team members in decisions, can prevent turnover and save your project.

Table 3-2 Description of Basic Emotions

Emotion | Description |

Anger | Most explosive and dangerous emotion. Violent anger is called rage. Anger can be used strategically. |

Fear | Perhaps the most important emotion—keeps us from being vulnerable to danger. Fears can be mistaken, exaggerated, and irrational. Panic, anxiety, and horror are related to fear. |

Love | Most complex emotion. Eros, philia, and agape are forms of love. |

Empathy | Sharing an emotion with another person, whether sorrow or joy. |

Sympathy | A “moral sentiment” at the very heart of human nature. Compassion. |

Pride | A positive evaluation of something one has done. A social emotion. |

Shame | Opposite of pride. One takes responsibility for the event or act. Guilt, embarrassment, regret, and remorse are similar. |

Envy | A desire to have what someone else has. Envy separates us, love is inclusive. Personal in nature. Spite is an escalation of envy. |

Jealousy | A social emotion that binds one with a rival who has the same desire. |

Resentment | The feeling that there is nothing one can do about one’s frustrations. |

Vengeance | The most violent and dangerous of emotions. The natural extension of resentment. It is an attempt to right a wrong. |

Grief | Grossly misunderstood emotion. Triggers thoughts of a lost loved one, but also provoke thoughts of one’s own mortality. |

Data derived from Solomon, R. (2006). Passions: Philosophy and the Intelligence of Emotions. Chantilly, VA: The Great Courses.

Like instincts, emotions are essential to our humanity. As we have evolved beyond solely identifying with the instincts transmitted by our reptilian brain, our emotions do not define us. We can separate ourselves from our emotions if we choose to. By separating ourselves from our emotions, by being mindful, our emotions do not control our behavior. We can choose to behave in a rational way no matter what emotion we are feeling. Being mindful—engaging our intellect to live in the gap between the stimuli and the response—causes fears to subside and anger to cool, preventing us from saying or doing things that are inappropriate and that we may later regret.

Once an emotion manifests itself, it intends to run its course, to be acknowledged and satisfied (Chopra and Tanzi, 2012). Emotions are not concerned with your efforts to be mindful and not to express them. In our mindful state, we can use our emotions to gain perspective on the situation without anyone else ever knowing what we are feeling. We may subconsciously display cues through body language, but most people will only be able to guess at what we are feeling. In this way, we experience life and enable ourselves to understand how others feel—their perspectives and the reasons for their behavior.

Two particular feelings—fear and desire—are closely linked. They both are rooted in our instinctive brains. They manifest themselves in our emotions, provoking us to act to resolve them, to alleviate the fear or to satisfy the desire. Unbridled fear and desire are dangerous. Unbridled fear can cause us to cower from trivial threats, such as the irrational fear of harmless bugs. Unbridled desire entices us to lust after things and people that are forbidden, even dangerous. We use our intellectual brains to keep our emotions in check, to control or prevent our response to these stimuli (Kehoe, 2011).

The limbic system is the control center for our emotions, but it also stores our long-term memories. It unites our senses—smell, sight, sound, touch—with memories and the emotions associated with those memories (Kehoe, 2011). Th rough these experiences and this link between memory, senses, and emotion, we learn and grow. These experiences are captured in long-term memory, anchored in emotions. They are triggered by senses and shape who are. They leave indelible impressions concerning our likes and dislikes, shaping our preferences.

Emotions and Subtle Forms of Communication

Let’s examine how emotions impact three forms of subtle forms communications, communications that do not rely on words: body language, tone of voice, and mirror neurons.

• Body Language. The activities in our limbic system influence our nonverbal behavior, our body language. Our body language provides indicators concerning how we feel, whether we are feeling comfortable and relaxed or whether we are feeling uncomfortable and stressed in response to events within our environment. Table 3-3 provides signals our bodies transmit unconsciously, signals that we can learn to observe in order to understand how those around us are feeling so that we can respond appropriately.

It is important to make a concerted effort to observe the body language of your team and coworkers. If you are an introvert, it may be natural for you to be absorbed in your own thoughts, but in order to have effective situational awareness so that you can be an effective leader, you must pay attention to others. This can help you establish a baseline of behavior for those around you. Then, when you notice that they perform an action that is different from the baseline, you will know that whatever is being said or is taking place in the environment has caused them some form of comfort or discomfort. If something stressful occurs, people engage in pacifying behaviors to make themselves more comfortable, and the greater the stress, the greater the likelihood of the behavior. Their body communicates messages to you that that they did not verbalize, messages that are important to you as a leader. If you observe and mimic their behavior, you will get a sense of how they are feeling.

• Tone of Voice. Researchers performed a study to analyze the tone of the human voice and the information communicated in tone. The research group was presented with recordings of doctors speaking to their patients. Some of the doctors had been sued for malpractice. The words in the recordings were muffled so that the audience could not tell what the doctors were saying and could only make out their tone. The audience accurately identified the doctors who had been sued for malpractice based on their tone alone. The doctors could not hide their frustration and resentment—their cognitive unconscious revealed their feelings in the tone of their voices (Kehoe, 2011).

• Mirror Neurons. Has someone ever smiled at you and you found yourself automatically smiling back? Have you ever looked at someone who was upset or sad and found yourself feeling the same way, even when you did not know why the other person was down? Many times when I yawn, my wife also yawns, and I find myself mimicking her when she yawns. Dr. Shad Helmstetter attributes these reactions to mirror or simulating neurons. This is an activity that simulates or infers the actions, feelings, or intentions of others. These neurons fire in our brains as though we are taking the action, even though all we are doing is observing the action. Dr. Helmstetter writes that mirror neurons also cause us to mimic the feelings and attitudes of others. These feelings and attitudes imprint on our brains, causing us to unconsciously respond to what they are experiencing. Neither you nor your communication partner realizes the communication is occurring (Helmstetter, 2013).

The phenomenon of mirror neurons is essential to communications. Critical communications, in which important information needs to be exchanged between IT project leaders and their key stakeholders, need to occur face to face as much as possible. Such a dialogue facilitates the processes of mirror neurons transmitting information, feelings, and attitudes between the IT project leader and the stakeholder. This transmission does not take place in email or video teleconference communications. Introverted IT project leaders can’t be shy about engaging in these faceto-face dialogues. The conversation enables them to communicate ground truth to the stakeholder and the stakeholder to communicate requirements to the IT project leader. Then, when the IT project leader communicates with team members, the stakeholder’s feelings and attitudes can be transmitted from the stakeholder, via the IT project leader, to the team.

Table 3-3 Body Language Activities and Interpretations

Body Part | Signs of Comfort or Pacification | Signs of Discomfort |

Face | People puff out their cheeks to release stress and to pacify themselves. People touch their cheeks to pacify feelings of nervousness, irritation, and concern. | People rub their foreheads when they are very uncomfortable or if they are struggling with something. People under stress may yawn excessively. People block the eye with their fingers and hands as a display of consternation, disbelief, or disagreement. |

Neck | People cover their neck dimple to pacify insecurities, concerns, even fears. People “ventilate” their neck areas to reduce stress and pacify themselves. | People touch their neck when they feel uncomfortable, doubtful, or insecure. Men adjust their ties when feeling insecure or uncomfortable. |

Shoulders | People shrug both shoulders when they don’t know something—there is nothing wrong with this. | People raise their shoulders toward the ears like a turtle hiding in its shell if the person is feeling humbled or suddenly loses confidence. People who shrug only one shoulder are sending an unconvincing message concerning their doubt or lack of knowledge. |

Torso | People bring themselves closer to each other when they are comfortable with each other. People splay out on chairs when feeling territorial and comfortable. People puff up their chests to establish territorial dominance. | People lean away from each other when they disagree. People suddenly cross their arms across their torsos and grip their arms when feeling discomfort. People breathe deeply, indicated by an expanding and contracting chest, when under stress. |

Arms | People raise their arms and perform other gravity-defying motions when they are happy and energized. People spread their arms over chairs to indicate they are confident and comfortable. | People withdraw their arms when they are fearful or upset. People put their arms behind their back when they do not want to make contact. |

Hands | People under stress will “cleanse” their palms on their laps to pacify themselves. This may occur under the table. People wring their hands when feeling stressed or concerned. People bite their nails when they are nervous or insecure. | People stand with their hands on their hips to establish dominance and to communicate their dissatisfaction. Around the world, finger pointing is considered offensive. People steeple their hands fingertip-to-fingertip when feeling confident. |

Legs | People cross their legs when they are comfortable. When people cross their legs and place their knee farther away from the person they are talking to, they are removing the barrier between themselves and the person they are talking to. | While sitting, people clasp their knees and shift their weight to their feet when they are ready to stand up and leave. When people cross their legs and place their knee between themselves and the person they are talking to, they are using their knee as a barrier. |

Feet | People point their toes upward when they are in a good mood, thinking or hearing something positive. People step toward other people when they feel comfortable with each other. | When standing, people turn their feet away from the person they are talking to when they are ready to leave, to end the conversation. People shift their feet from being flat-footed to “starter position” when they are ready to leave. People maintain a distance from or step away from other people who they do not feel comfortable with. When sitting, people kick their feet when they feel discomfort. Someone who normally wiggles or bounces their feet while sitting and then suddenly stops when something is said or occurs is feeling stressed or threatened by the event. People will suddenly interlock their legs or lock their legs around a chair when feeling discomfort, anxiety, or insecurity. |

Data derived from Navarro, J. and Karins, M. (2008). What Every BODY is Saying: An Ex-FBI Agent’s Guide to Speed-Reading People. [Kindle]. William Morrow Paperbacks.

In our mindful state, we are capable of using our intellect to develop more creative solutions than running away or fighting back. Our instincts sense a situation; our emotions process and categorize it, relating it to similar situations; and our intellectual brain creates a strategy—a plan of action—to satisfy the feeling. Instead of fighting the bully when attacked, we can devise a way to conduct a surprise attack; instead of forcing ourselves on a potential mate like a Neanderthal, we develop a strategy to woo her.

Humans have an internal voice—self-talk—consisting of continuous communion between the emotions and the intellect. This speech may be an internal monologue for some or an internal dialogue for others (Chopra and Tanzi, 2012). Should we listen to our brain’s internal monologue, drawn from irrelevant habits, old memories, and obsolete programming? Or should we engage in internal dialogue and explore new ideas and approaches? As leaders, we must learn from and then influence our environment to achieve project success.

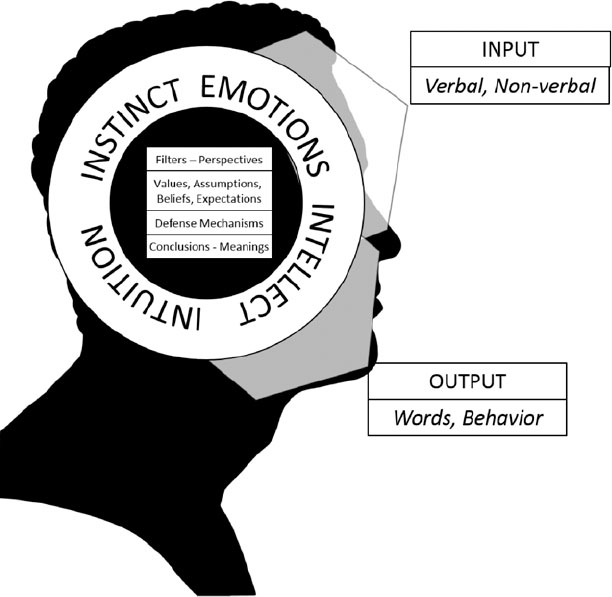

Intellect is driven by our internal dialogue, enabling us to ask questions and seek knowledge. We not only experience life, we also analyze it and learn from it. Not only do we learn about experiences, we learn how to think about our experiences (Kehoe, 2011). When events occur in life, our instincts, emotions, and intellect help us react to those events in sophisticated ways, as Figure 3-2 indicates.

Thinking about our experiences requires self-awareness. Self-awareness dwells in our consciousness and requires intellect. Our instincts and emotions reside in our subconscious. We blend our conscious and our subconscious instincts, emotions, and the knowledge gained from experience in our intellectual brain. When our subconscious thoughts and impulses drive us into situations in which we find ourselves unhappy, our intellect seeks better experiences (Chopra and Tanzi, 2012).

The intellect enables understanding. Instead of mindlessly reacting to situations, intellect enables us to analyze a situation and create a response (Chopra and Tanzi, 2012). The intellect is capable of analyzing instinctual impulses and preventing mindless reactions. It is capable of corralling emotions, holding them back or expressing them consciously. It is capable of anticipating and understanding the instincts and emotions of others and preparing a mindful response to their words and behavior.

Figure 3-2 Instinct, emotions, and intellect.

Our intellect enables us to make connections with others, to have empathy for them so that we can relate to their instincts and what they are feeling. This connection leads to understanding. We craft verbal communication to engage their intellect, asking questions to understand what they are sensing, how they are feeling, and the rational for their reasoning—what and how they are thinking. We share what we are sensing, our feelings, our memories of relevant experiences, and our judgment. Through dialogue, we learn about each other, and we are able to teach one another. Our verbal and nonverbal communications, subconsciously transmitting our inner anxieties, desires, and preferences, enable us to connect at a deeper, more human level, a level of understanding that connects us emotionally and spiritually. We can find common ground through a a shared vision and mission, understand each other’s objectives and approach, and understand each other’s needs and how we can help each other fulfill those needs.

Using our intellect in this manner—being mindful of our own impulses, emotions, and thoughts and their relation to our situation and that of others, being mindful of how our words and actions as leaders impact others’ behavior—gives us the ability to influence situations. We have a responsibility to influence others in positive ways and to avoid being manipulative and abusive. The International Information Systems Security Certification Consortium (ISC)2 provides an excellent example of an ethical standard that individuals and organizations should adopt and strive to implement consistently. This code demands adherence to individual integrity, including honesty, respect for the law, avoidance of conflict of interest, and treating others with respect ([ISC]2, 2010). Employing power as leaders must be done with care and understanding, as we are depositing memories and invoking emotions in other human beings. We are responsible for making this a rewarding experience and for avoiding creation of painful memories.

The conscious mind thinks in words and pictures. Intellect and intuition use words and pictures to help us understand and respond to the world around us. The conscious mind does not access the cognitive unconscious mind directly because its memories are composed of biochemical patterns, not words and pictures. The cognitive unconscious mind lives in the limbic system, the source of our feelings and long-term memories. It continuously receives input from all of our senses while we are awake, looking for and remembering patterns, annotating those patterns with emotions, with somatic markers for later retrieval (Kehoe, 2011).

Dictionary.com defines gestalt as “a configuration, pattern, or organized field having specific properties that cannot be derived from the summation of its component parts, a united whole.” As leaders, we are bombarded with information from a multitude of sources, such as users, team members, peers, our senior managers, other teams, and competitors. The complexity of implementing and supporting high-tech solutions, the difficulties of communicating abstract ideas concerning technical requirements to developers and engineers and of explaining abstract technical solutions to customers and users, the myriad unpredictable personnel issues—all of these chaotic elements come together to create a dynamic challenge for IT leaders. The summation of these complex elements can create on overwhelming morass, a morass that is larger than the sum of the individual organizational elements.

This situation may seem difficult to manage effectively. The stimuli from the various sources is received too quickly to process in a timely manner using rational, logic-based thought. A typical decision-making process includes defining the problem, collecting data, developing and testing alternative solutions, and choosing the best solution. There is not enough time or enough management manpower within organizations to execute this process for all decision requirements within IT environments.

Intuition enables IT leaders to navigate through the morass of complexity in their environments. Gestalt psychology enables us to build dynamic correlations between our perceptions and experiences. It combines our instincts, emotions, and intellect to produce an overall image of reality, enabling us to make snap decisions. Recent studies have shown that intuition is a faster process than rational decision making. These intuitive decisions are influenced by what we sense, our memories, and our experiences.

Intuitive leaders can prevent problems. Like the Jethro Gibbs character in the American television series “NCIS,” their “gut” warns them of issues and directs them toward solutions. They sense when issues are likely so they can then take proactive measures to prevent them. This requires leaders to be in tune with their environment through the management and monitoring of communications, having dialogue with stakeholders on a regular basis, performing informal and formal relationship management.

First impressions and snap judgments—those based on the combination of our instincts, emotions, intellect, and intuition—are often the most accurate (Chopra and Tanzi, 2012). Our intuition enables us to make creative leaps, to understand facial expressions and body language, to know when someone is lying, and to otherwise feel our way through complex situations. As IT leaders in complex and dynamic environments, we must trust our intuition, using our minds in a holistic way, in order to navigate our way to project success.

3.3.5 Schemas and Communications

Our intuitive mind automatically refers to schemas. A schema is a concept or framework used to organize and interpret information. Schemas are mental molds into which we pour our experiences, like data stored in database tuples. We then, in our cognitive unconscious, use these schemas to organize and interpret unfamiliar information. We draw on these schemas to understand our world and to communicate with each other. During communication, we endeavor to connect the schema in our own minds to the schemas in the minds of others such that it correctly describes our message. When our schemas are different, when we do not have the same experiences, when we do not use the same language or use unfamiliar jargon, communication becomes difficult. When there are no references between the data in our databases and the data in our communication partner’s databases, we can’t understand each other.

When the ideas we formed about reality are wrong, and we are not seeing the same truth, communication becomes even more challenging, as the schemas we draw from would not make sense to our communication partners.

It takes very little effort to create a first impression. When we take things at face value in conscious thought, and when we are wrong, we create an erroneous schema within the mind of our communication partner, a schema that becomes the basis of decision making. When we use abstract words and judgmental language to explain ourselves, but the listener does not understand and does not ask for clarification, the listener applies his or her own schemas to fill in the blanks, whether correctly or incorrectly (most likely incorrectly when little effort is expended). It is easier for the listener to make assumptions—assumptions easily regarded as facts—than to make the effort to obtain clarification and understanding. These assumptions will most likely be made based on their past experiences—different schemas that are not relevant to the situation at hand. The easier it is to recall those experiences, the more likely our communication partners believe their recollections and associations are true (Kehoe, 2011).

The more abstract our talk, the more we leave out information, and the more we rely on others to fill in information using their own schemas, which may be different from ours and not what we intend. As mentioned earlier, meanings are in people, not in words. Our communication partner fills in this information at the cognitive unconscious level; it is filled in automatically and faster than the conscious mind can process the data. The conscious mind then draws conclusions based on the stimuli from the cognitive unconscious, stimuli that is packaged with emotions and memories, stimuli that our conscious minds integrate with our beliefs. Once our beliefs are added to the package that includes our emotions and assumptions, we are ready to respond through words and actions—a conscious response that can be far removed from the current reality, a response that could be based on a distorted and garbled message.

No wonder Osmo Wiio, a Finnish professor of communications, was so sarcastic when he developed his communications “laws.” He said, “Communication usually fails, except by accident.” He also said, “If a message can be interpreted in several ways, it will be interpreted in a manner that maximizes the damage.” Finally, he said “There is always someone who knows better than you what you meant with your message” (A Commentary on Wiio’s Laws, 2015).

Organizations have their own norms for communications, influenced by society. Similar to the manner in which organizations have different dress codes, organizational norms dictate the methods and forms of acceptable communication: who is allowed to deliver messages to whom; acceptable ways to express emotions. There is knowledge, processes (habits), history, and tradition in organizations that create common schemas in their members’ minds. When new people join those organizations, they are indoctrinated into those schemas. To effectively communicate, leaders must understand the organization’s norms and know when to utilize them to deliver and receive information, or when to exercise the courage to defy them when important messages are not being heard.

I once led a Microsoft Active Directory and Exchange migration project for a critical government customer. Our team was not getting the information we needed from the infrastructure group to move the project forward. I had numerous meetings with the project sponsor to stress that we needed their cooperation in order to stay on schedule. The senior members of my project team and I became frustrated, and together we crafted an email message that expressed our concerns and frustration. We were less than diplomatic, calling out senior members of the infrastructure group in our message. As we were contractors, we violated a norm or two by sending this message without clearing it with our government sponsor. Our message caused political problems for our sponsor and his superiors. They had to perform political damage control. If I were not the PM for the contract, and if the project were not as critical as it was, I could have been relieved of my position. Partly because of our courageous act, we did eventually get the cooperation we needed. However, it came at a political cost.

The schemas in our minds help us organize and interpret information about the world we live in. Let’s take a look at how our interpretations of these data influence our behavior.

3.4 The Rational-Emotive Behavior Model

The Rational-Emotive Behavior (REB) Model (Ellis, 1962) explores how individuals process external events and how the results of this processing impacts their behavior. It describes the relationships among values, assumptions, beliefs, and expectations (VABEs). People are emotionally impacted, feel psychological dis-comfort, when their VABEs are threatened, and they use defense mechanisms to protect their psychological well-being. People draw conclusions about themselves and about their external environment based on what they perceive in comparison to their VABEs. These conclusions impact their behavior, what they do and what they say. If their perceptions are in line with their VABEs, they may behave in a positive way. If their perspectives are out of sync with their VABEs, they experience psychological discomfort and may become defensive if they feel threatened.

Figure 3-3 builds on Albert Ellis’s REB Model. I expanded the model to account for the human instincts, emotions, intellect, and intuition discussed earlier. I described the model within the framework of the basic input, processing, and output computing model familiar to IT professionals:

• Input: REB activating experiences or adversities

• Processing: Inside the human mind—REB beliefs, ideas, and philosophies about adversities

• Output: REB consequences and results

Table 3-4 provides definitions for the terms used in Figure 3-3.

Figure 3-3 REB Model with intuition, emotions, intellect, and intuition. [Data derived from Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. NY: Lyle Stuart.]

Many therapists and researchers consider defense mechanisms when analyzing human behavior. Defense mechanisms have significant influence on our response to the world, as we use them to protect our wellbeing. Several widely used defense mechanisms are provided in Table 3-5.

This modified REB model addresses the instincts, emotions, intellect, and intuition along with the VABEs, perceptions and filters, defense mechanisms, and conclusions within the mind of one person. This framework becomes more interesting when we add a communication partner. Instead of a stand-alone system with its own input, processing, and output, we now have a communication process, a network that integrates those systems.

Term | Definition |

Filters—Perceptions | Perceptions result from the process of organizing and interpreting sensory information, enabling us to recognize meaningful objects and events (Meyers, 2007). These activities enable living beings to order and interpret the stimulants received into meaningful insight. We all have different interpretations to stimulants, and therefore, we filter events differently and sometimes inaccurately (Perception, n.d.). |

Values | Values are judgments about how important something is to us (Values, n.d.). |

Assumptions | Assumptions are the premise or supposition that something is a fact; therefore, this is the act of taking something for granted. Assumptions represent how we think things should be (Assumptions, n.d.). Beliefs A belief system is a set of beliefs which guide and govern a person’s attitude. Usually, it is directed toward a system such as a religion, philosophy, or ideology. Attitudes and beliefs in these systems are closely associated with one another and are retained in memory (Belief, n.d.). |

Expectations | Expectations are the state of tense and emotional anticipation. We experience psychological discomfort when our expectations are not met (Expectation, n.d.). |

Defense Mechanisms | Defense mechanisms are the unconscious reaction the ego uses to protect itself from anxiety arising from psychic conflict (Defense Mechanisms, n.d.). |

Conclusions | Conclusions are the offer to which a stream of analysis or opposing matter leads. Conclusions lead to feelings (Conclusions, n.d.) |

Term | Definition |

Denial | Refusal to admit a threat is relevant or that it will occur |

Avoidance | Refusal to face the threat |

Rationalization | Making excuses to explain away threats |

Intellectualization | Complex rationalization of threats |

Displacement | Redirecting reactions from a more threatening activity to a less threatening activity or action |

Projection | Attributing negative emotions to others rather than accepting them |

Regression | Reverting back to an earlier, less mature state |

Data derived from Kehoe, D. (2011) Effective Communications Skills. Chantilly, VA: The Great Courses.

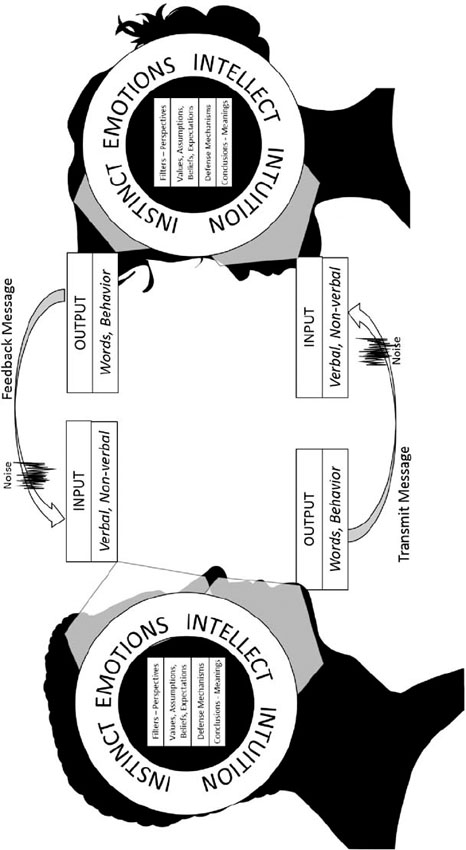

3.5 The Communications Cycle and the REB Model

To communicate with emotional intelligence, you need to consider what we have learned about how the mind works within the context of the classic communications cycle. Figure 3-4 depicts the integration of the modified REB model presented in Figure 3-3 with the classic communications cycle.

The sender, on the left side of the graphic, formulates the message. This message is the result of a conclusion drawn from what the sender senses, how he feels, what he believes, and what he thinks—all of the elements present in the mind of the sender. The sender has a mental picture in his mind that he needs the receiver to understand. He needs to describe his intent with consideration of the meaning that he feels resides within the receiver.

The sender encodes into words that he feels describes his intent and sends it over a communication channel to the receiver. This communication channel may be the sender’s voice, an email, an instant message, or some other medium. If the sender and receiver can see each other, the sender may use gestures to emphasize and strengthen his message.

The message, once encoded and transmitted, is subject to noise. The noise may be in the form of distractions, poor encoding, language barriers, and dialects. The sender’s emotions will impact the message he delivers, perhaps through voice inflections or body language, and will do so subconsciously.

Figure 3-4 The Modified REB Model integrated with the Classic Communications Cycle. [Data derived from Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. NY: Lyle Stuart.]

The receiver receives the message, and immediately her cognitive unconscious mind, influenced by the somatic markers in her limbic system, matches patterns it perceives in the message with previous patterns. This happens very quickly, before the receiver’s intellect and intuition can process the signals received and draw meaning from them. She senses and filters both verbal and nonverbal inputs, deciphering the sender’s feelings about the message through observation of his voice inflection and body language. She may mimic his actions through her mirror neurons, feeling what he feels. She subconsciously analyzes not only what he says, but how he says it. Once a pattern is found—a schema that helps her perceive the message—she may experience biological changes such as an increased heart rate, sweaty palms, changes in breathing patterns—changes that cause comfort or discomfort depending on her interpretation of the message, on the schema that she relates to the message. She then applies her own values, assumptions, beliefs, and expectations to the message. If she perceives that information is missing or if there is information she does not understand, her cognitive unconscious adds her own assumptions and conclusions to the package. The more abstract the message, the more information that the sender has left out, the more information she fills in on her own.

Research has shown that the receiver will take what she hears at face value, placing a high value on information that is easy for her to recall. She will classify what she hears and perceives based on cases in her past, treating the assumptions she makes as facts (Kehoe, 2011). Her conscious mind applies its intellect and intuition to the message. She will consider her interpretation of the content and the emotions associated with the content to reach her conclusion.

If she feels threatened by the message, she may unconsciously invoke defense mechanisms to protect her own psychological discomfort.

The stream of information from filters and perceptions, VABEs, and defense mechanisms lead to conclusions about the message. These conclusions result in feelings. Now, her intuition will give her a sense of the real meaning of the message, holistically considering all of the stimuli she has received. Does she trust the sender? Does what he is saying seem right?

Her intellect rationalizes the message and seeks to understand it. She may form a question concerning the message or decide on the value of the message. Does it make sense? Is it within context—is it relevant to the discussion? Does she need more information? Perhaps she quickly understands exactly what is being said, or perhaps she forms her own opinion about the message. She may challenge it or support it. She forms a mental picture in her mind and then encodes that picture into words and behaviors. This output needs to address the meaning of the message that she perceives within the sender.

She transmits her message over a communications channel. Her feedback is subject to the same noise that affected the message she received.

The sender of the original message processes her feedback in the same manner as the receiver processed the message she received from him. He applies filters and perceptions, VABEs, defense mechanisms, and conclusions using his cognitive unconscious mind. His intellect enables him to learn from her feed-back, and his intuition enables him to draw meaning from all of the stimuli and thoughts he experiences. He makes a determination as to whether the meaning he attempted to convey to her was successfully transmitted, received, and understood, and then he responds accordingly. The cycle begins again and the dialogue continues.

All of this happens very, very quickly, with the instincts, emotions, intellect, intuition, VABEs, filters, perceptions, defense mechanisms, and conclusions firing within the minds of both the sender and receiver simultaneously. Messages are encoded, transmitted, and decoded faster than data packets over a wireless network.

Not only do the sender and receiver focus on the message they are transmitting, but also how they feel about themselves and about each other impacts the success or failure of communications.

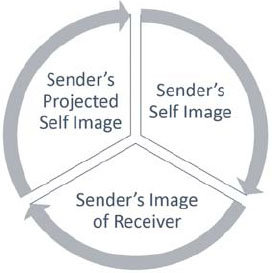

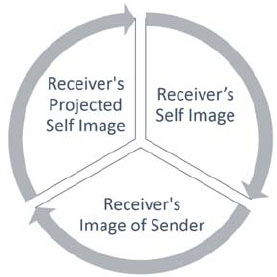

3.6 The Communications Cycle and Self-Images

Our self-images give us a sense of our personality. Self-images reflect our success in relationships and our wellbeing (Self-Image, n.d.). During the communications process, we maintain three images in our minds: our own self-image, our image of the receiver, and the image we want to project to the receiver as depicted in Figure 3-5 (Kehoe, 2011).

Figure 3-5 Sender’s images.

The sender’s image of the receiver is based on what the sender believes about the receiver’s values, assumptions, beliefs, and expectations. The sender will make judgments about the receiver’s ability to understand the message and will try to anticipate her response to the message. He may make assumptions about her background—the schemas she has stored in her mind—and then craft his message accordingly. For example, if the sender is providing the status of a software development effort, and he believes the receiver does not understand software development, he may educate her on the basics of Agile Software Development Methodology before providing the status.

The sender will project the self-image that he wants the receiver to see. For example, if he wants to appear to be educated and competent, he may use Agile jargon in his message such as “scrums” and “sprints” in order to shape the image he projects to the receiver. Think of the projected self-image as your profile on Facebook, LinkedIn, Google+, or some other social network. You post information to present the image of yourself that you want people to see, not the deep, dark secrets that compose who you are.

If the sender is an introvert, as most IT geeks are, his self-image reflects someone who prefers internal communications to external communications. However, the IT geek can present a projected self-image of someone who is an effective communicator. Projecting this image for long periods is draining for most introverts, as it requires a lot of energy. It requires the IT geek to use his or her less preferred Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) style, as discussed in Chapter 2. However, through positive self-talk, mentorship, and practice, the introverted IT geek can learn to communicate effectively, much as a right-handed person can learn to write with his or her left hand.

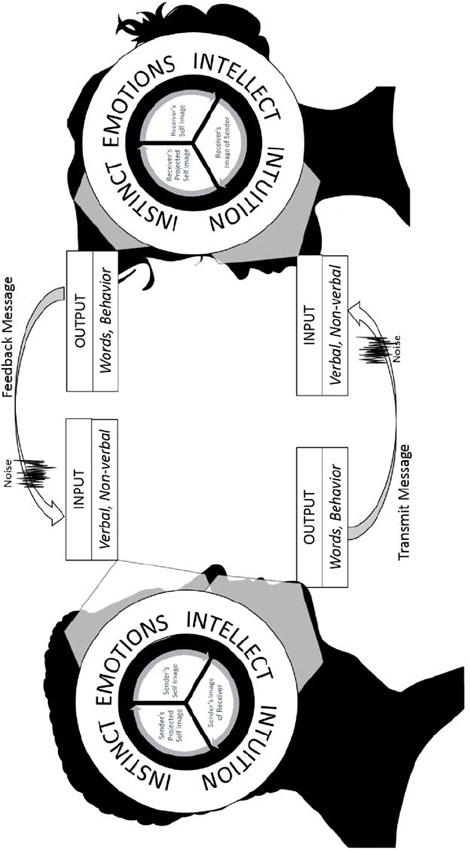

The receiver will have her own impression of the sender and will attempt to project the image of herself that she wants him to see. Figure 3-6 represents the receiver’s images.

Figure 3-6 Receiver’s images.

If the sender and the receiver have negative impressions of one another, there could be negative impacts on the communications process. What if the receiver is a business executive who believes that IT geeks are not sophisticated enough to understand the company’s business requirements? This bias creates mental noise that inhibits the sender’s message from getting through. What if the sender is an IT leader who is intimidated by his perception of the business executive’s image? This fear could lead to a distorted message that leaves out the ground truth concerning a delayed project schedule, for example—information the business executive needs to create accurate forecasts.

Overlaying these images on the communications cycle, with respect to human instinct, emotions, intellect, and intuition, produces a dynamic image of the communications process as shown in Figure 3-7. All of the elements of Figure 3-7 are active simultaneously during the communications cycle, even for the simplest interactions.

Both the higher-order senses and the lower-order, primitive senses are involved in projecting and observing images of the senders and receivers. The senders and receivers may feel sexual attraction, or repulsion, for one another. These primitive stimuli occur automatically, before the intellectual mind can process the signals. The intellectual mind decides how to respond to the feelings, but it does not operate quickly enough to prevent the feeling. I once heard a story about a customer who was on the selection panel for awarding a large US government contract. While she was listening to the oral presentations from the bidders, she found a particular presenter to be quite attractive and had a hard time concentrating on his company’s presentation!

Again, the thought processes that take place during communications occur very, very quickly and are extremely complex. Human communications are prone to error. In the complex environment of IT projects, communications cannot be taken for granted but must be approached with diligence in order to promote understanding. IT leaders and team members need to understand each other, and the IT team needs to understand the customer and his or her requirements. This understanding can lead to reduced complexity in the environment, improved communications, and an increased probability of project success.

Dialogue is the mindful way to make connections with people and to enable people to understand each other. Problems are solved through dialogue. Pro fessor Dalton Kehoe of York University describes what I have labeled the Talk Continuum, provided in Table 3-6. The Talk Continuum provides a framework for understanding the types of communications we engage in. It progresses from internal and automatic evaluations to external and deliberate dialogue. This connection between internal thoughts and external communications demonstrates the link between our internal selves and our relationship with others.

Figure 3-7 Communications cycle with sender and receiver images. [Data derived from Ellis, A. (1962). Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy. NY: Lyle Stuart.]

Talk Type | Description |

Self-Talk | Automatic and constant internal self-evaluation and evaluation of those around us. Negative self-talk can emotionally hijack a person and render them ineffective. Positive self-talk builds confidence and self-esteem. |

Connect Talk: Procedural | Used to get through every-day situations. This is the conversation we have when making a purchase or ordering food. Procedural control talk is the expected behavior of “normal” people. |

Connect Talk: Ritual | Ritual recognition or greetings such as when one asks, “How are you?” and the other responds “fine.” Demonstrates ability to participate in social roles in the community. |

Connect Talk: Small Talk | Provides a safe way for people to get to know each other. Provides the opportunity for participants to move from first impressions to more significant relationships. |

Control Talk: Light | An automatic response to differences and disagreements. A form of problem solving where one person tries to persuade another. One tries to dictate to the other how he or she should think, act, or feel. |

Control Talk: Heavy | The escalation of light control talk. A natural, yet ineffective, human response to conflict. Uses more negative tactics to overcome resistance. Undermines the integrative, connective nature of the relationship. |

Dialogue | A conscious choice to be mindful and appreciative in order to solve a problem, not to “save face.” Requires management of emotions and the pursuit of understanding. |

Data derived from Kehoe, D. (2011) Effective Communication Skills. Chantilly VA: The Great Courses.

The point of emotionally intelligent communication is to maximize dialogue and minimize control talk. It requires active listening, engaging both you and your communication partner. It requires you to focus not on yourself but on your communication partner and what he or she is saying. Most IT professionals are introverts, and if you are one of them, you are probably perceived as a good listener. Active listening is an opportunity for you to exercise this strength.

Your cognitive unconscious will automatically try to relate what you are hearing to your own schemas. You need to be mindful of what your communication partner is saying and what he or she means, not focusing on how you will reply. Dialogue is not a competition of who can talk more or who can make the most points. It’s about actively listening and understanding, asking the “who, what, when, and how” questions that will lead to the why. This leads to the efficient attainment of ground truth.

As Steven Covey advises, we should seek first to understand, then to be understood (Covey, 1989). I once worked with a senior leader who had just recently taken on responsibility for a large services firm. This leader had a tremendous amount of experience and was anxious to make his mark on the organization. However, during the first few months of his leadership, all of his meetings were very tense. He struggled to make what he believed to be improvements without understanding how the organization worked and why his predecessors made the decisions they made. His interactions with his staff escalated to a dysfunctional level. He would frequently disparage staff members in formal meetings and curse at them in informal meetings. This heavy control talk did not contribute to resolution of the firm’s problems. Instead, it damaged the relationship between the leader and his staff, making problem solving more difficult.

Over time, the leader learned more and more about the organization and felt comfortable enough to engage in dialogue with key staff members. He learned to ask questions about the environment, and he learned from experience what was required for the firm to be successful. The firm moved forward. However, it would have been successful sooner if the leader had heeded Covey’s advice and sought to understand before being understood, engaging in dialogue that led to relationships based on mutual respect and so to the resolution of problems.

Emotionally charged control talk distracts from problem solving. With control talk, our energy is spent in emotional and intellectual competition instead of on reducing complexity and increasing understanding.

The enemy of efficiency is complexity, and dialogue defeats complexity. It is the weapon of choice to facilitate understanding, leading to better IT solutions.

3.8 Analysis of the Missed Signals Use Case

In the Missed Signals use case introduced earlier in this chapter, Mark, the disgruntled team member, did not have a favorable perception of Karen, the new supervisor, because of how she addressed the issues of data accuracy. Karen used heavy control talk and did not engage in dialogue concerning the issue. She could have been experiencing an “amygdala hijacking,” making it difficult for her to think rationally about her behavior and its impact.

Mark was very uncomfortable while Karen was talking, and he hid his angst by wringing his hands underneath the table. He did not believe he was lazy, and he was hurt by Karen’s accusation. Her appearance while she spoke made him nervous and fearful. Karen’s behavior did not meet his expectations for a supervisor, did not fit his schema for how a supervisor should treat an employee. Mark had suppressed his desire to search for another job. However, his fears were revived after Karen’s rant. He felt powerless to fight, so he decided to flee.

Tony, the project manager, knew about Karen’s behavior, and he did speak to her about it, but he did not have a relationship with Mark. He had spoken to Mark in meetings and had offered to speak with any of the team members one-on-one. The conversation between Mark and Tony never happened. Tony had no intuition concerning what Mark was feeling. They did not understand each other. There was no VABE connection between the schemas in Mark’s mind and those in Tony’s. As a leader, Tony had no impact on Mark’s behavior.

Mark did not provide feedback to Karen or to Tony. Karen did not know how she needed to adjust her message to ensure that Mark understood the urgency of the matter and how the team members needed to adjust their behavior. She had no idea of how her message made Mark feel. Mark’s feedback was provided to Human Resources, then to Tony, and then back to Karen. By the time Karen received the message, it was too late to have an impact on Karen’s relationship with Mark.

Mark’s expectation was that the PM would not allow a supervisor to treat team members in the way Karen had treated them. Yes, Mark was assigned to a high-visibility and high-pressure project, but this was not an issue for him because he was as emotionally resilient as any other IT professional. However, Mark’s values included self-respect, and he would not allow himself to be disrespected. He concluded that if Tony was not going to handle the problem with Karen, Human Resources would.

Human Resources never made a connection with Karen. Operating in accordance with their policy, Sandra from HR spoke to the PM, Tony, about the personnel situation, and then Tony relayed the message to Karen. It worked like a bad game of “telephone.” By the time the message traveled from Sandra, through Tony, to Karen, it had been distorted. Karen never understood HR’s intent. She did not know their interpretation of the events, their feedback from Mark, or their rationale for assigning the communications courses.

The corporate picture within the mind of HR was not successfully transmitted from Sandra to Tony to Karen in a way that connected to Karen’s values, assumptions, beliefs, and expectations. Karen did not have an opportunity to ask questions, to provide feedback and obtain clarification. This disconnection caused uncertainty within Karen’s mind, uncertainty that led to fear concerning her job.

Tony and Karen never made a connection. Karen was close to the previous PM, and her management style was closer to his than to Tony’s. But Tony never would have treated the team members the way that Karen had. He had taken steps to coach her and to set expectations concerning how team leaders were to behave. He provided her with the training recommended by Human Resources. However, Karen harbored resentment concerning corporate issues outside of Tony’s control. Her expectation and belief was that Human Resources would allow her to rebut complaints against her, would allow her to tell her side of the story.

Karen told Tony she would provide “whatever he needed,” but she said this with her back turned to him as she walked away. Her body language was not consistent with what she said. It was, however, an indication of what she meant. Karen made the same choice as Mark did: relieve the psychological discomfort by fleeing rather than fighting.

I have lost good people from my team because I was not in tune with them and the issues they faced. Many times, when key team members left, it took us several months to find replacements. Our productivity for the tasks assigned to those positions suffered. As an introvert, I had to learn to pay more attention to body language and demeanor. I had to pay more attention to the project’s most valuable asset, its people. As a leader, it is my job to make them feel important and appreciated.

People issues are complex and can derail your project, whether those people are your team members or your stakeholders. To get and stay ahead, find the ground truth as quickly and efficiently as possible.

Bonnie Smith, Senior Vice President of IT and Industrial Sector CIO at Eaton, cites cultivating casual conversations as a secret to project success (Smith, 2014). “As IT leaders who are most often schooled in engineering disciplines, we sometimes forget that the best governance practices are, in the end, executed by a wildcard—namely, people,” she told CIO Magazine in September 2014. “Often, the people who report to us will, through a surplus of good intentions, suppress any rumblings on the ground in the updates they give us, concealing the fact that milestones are quietly being missed. What is needed is an honest dialogue, which is often stymied by a fear of disappointing the boss.

“As CIO, it is absolutely critical to ensure that you, personally, build relationships with the speakers of truth,” she continues. “You must identify the people who will tell you that what you’re being told isn’t what is really happening. The most common way to gain these insights is through an off hand comment someone makes in casual conversation, since lower-level staffers may worry about stepping on someone’s toes during formal meetings.”