Case Study

John Darwell

John Darwell is an independent photographer and a Reader in Photography at the University of Cumbria. His long-term projects reflect his interest in social and industrial change, concern for the environment and issues around the depiction of mental health.

RESEARCH IN ITS VARIOUS FORMS is inherent within all my projects now, but this has not always been the case. Undertaking a PhD strongly influenced my ideas about the nature of research and how as part of the creative process it is imperative to have an in-depth understanding of the subjects that interest me. All my work prior to that point had been documentary in approach and had a very strong polemic. The projects were concerned with my personal take on social or political issues and, looking back, I see how this was a rather self-righteous attempt to set the world to rights, and I was becoming uneasy about it. Not only about my own work, but also about quite a lot of the work that I was seeing at the time, and I know exactly when that started.

I had just come back from Chernobyl where I had been photographing within the exclusion zone. A no-entry area with a 30-kilometre radius that was evacuated after the nuclear meltdown at the Chernobyl Power Plant in 1986. The area contained one major city, Pripyat, and over 70 villages and scores of farms. The people living in these locations were given 24 hours to gather their possessions and were then moved to locations around the Ukraine, in most cases never to return. On my arrival back in the UK, the press had written about my having risked my life in such a dangerous place, which wasn’t the case. I’d gone there, taken some photographs and then left again with everyone patting me on the back and saying I was a hero; but I was just a glorified tourist who chose to go there. The people affected by the disaster in Chernobyl had no choice but to live with the consequences every single day of their lives.

Between completing the Chernobyl project and starting my research degree I began thinking that I had to change the way that I looked at the world, and the kind of work I was making. What became important to me was to look at issues that were relevant to my life rather than attempting to impose my world-view on other people’s situations in the way I had been doing. As a result my work became far more intimate, looking from an internal perspective rather than an external one, and importantly, equipping myself with the necessary knowledge to make informed decisions appropriate to each project.

The research process helps me to understand what it is I’m looking at, and helps me to understand why I am drawn to certain subjects. This generally involves background reading and includes literature from a range of relevant sources. Depending on the project this could encompass historical or social perspectives to environmental concerns. This helps me to underpin the arguments I want to engage with, which would then be combined with visits to specific locations if appropriate. But as part of that process I also think it is important to look at what other photographers and artists are making work about. How others have thought about and approached certain subjects can be very stimulating.

I know many photographers concentrate purely on the visual, spatial relationships of how elements sit within the frame, which is important to me, but I’m not that interested in the mechanics of photography as such. Much of my work tends to involve quite intimate close-up perspectives with a lot of differential focus. This came about sometime in the 1980s when I moved from using a rangefinder camera for all my projects to using a through the lens camera. Suddenly, I could see through the layers of focus, and this is something that continues to be a fascination and a delight to me, even after decades of observing the process.

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

But it is the research I do that ultimately influences what the final work will look like. In many ways my work has responded to things discovered within the research process, and for me is a crucial part of my creative process. I cannot imagine undertaking any project without having engaged in a process of research, my work would be far more superficial without it.

Research also helps to extend the boundaries of my work because the research process is by definition about taking risks; unlike my earlier work, which could be considered quite safe in that I had a reasonable idea of what I was likely to end up with. Research materials have to be interpreted and to do that you have to continually ask questions in order to examine and understand what emerges. Often, this is about finding reference points that take me in different directions and bring the work together in new or unexpected ways.

The unease with my initial documentary approach I mentioned previously was reinforced by a personal event in my life that led me to turn to photography in a more inward-facing and expressive way. In the 1990s I suffered an extended period of clinical depression, which sometimes left me unable to function on a number of levels. Following my rehabilitation I wanted to understand what had happened to me, and I began a concentrated programme of research that eventually led to the series A Black Dog Came Calling. The initial premise for this was to explore the possibility of creating a body of work that would approximate the experience of depression, in a manner that could be recognised or understood by others with first-hand experience of the condition.

The project ultimately led to my gaining my PhD and became a huge undertaking. It was a very different experience compared with the familiar context of my arts practice. For most arts practitioners whatever the discipline, research has a small r. By this, I mean that research involves activities that are fundamental to the development of the artist such as experimenting with the tools of the trade and pushing the boundaries of their

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

practice through subject matter or specific goals. In this context the research is largely invisible or completely hidden, and the only concern is with the work itself. With a PhD the research has a capital R and it is the research process that is under scrutiny. The images are just one step in a broader inquiry that is judged by the significance that the research brings to the subject area, in other words the research has to contribute something original to the knowledge pool.

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

The contextual research for the Black Dog series involved reading around the subject including the history, current medical literature and looking at how mental illness had been depicted visually, and certain things came to light. A benchmark had been set sometime back for the representation of someone suffering from melancholia or depression. This often took the form of a solitary figure sat with their head in their hands in the corner of some darkened room, which I personally found very frustrating. There is no shorthand for depression, no ‘one size fits all’ and I wanted to get away from a clichéd image that only served to block understanding and undermine the complex and unique nature of mental illness.

Reading first-hand accounts by people with depression provided the most relevant information for me. What this did was to allow me to understand that the experience of others with mental illness wasn’t that far removed from my own. I was interested in the signifiers that were in their writing, phrases such as ‘… the black hole’ or ‘… darkness’ or ‘… the grey light of depression’. I recognised these terms and they had a resonance for me, which fed into my work as elements from my own experience. I began to consider that, if that was the case then, I could maybe develop a language of universal signs that could be recognisable to others. In essence, it wasn’t what was in the photographs that counted, but how they made me feel. The subject matter somehow had to spark a sense of recognition within me, to approximate some element of my own experience of depression.

I began the work with the idea that what I had experienced, although specific to me, may have overlaps with other people who had experience of depression first hand or who had witnessed the depression of someone close to them. I wanted to create something that was well and truly grounded in reality, but a reality that was internalised, not necessarily a visible reality. I had to find a visual language based on the real world but using metaphor and for quite a time that old Garry Winogrand quote had been going round in my head: ‘I take photographs to see what things look like photographed.’1

So, how does this influence my practice and how I go about taking photographs? I have never been very good at isolating what works in the viewfinder, so I take an awful lot of photographs to evaluate later. What I am interested in is the photographic-ness of things and exploring the nature of photographic seeing, which was something I had already begun to explore in my earlier projects, but this has become a more explicit aspect of my work.

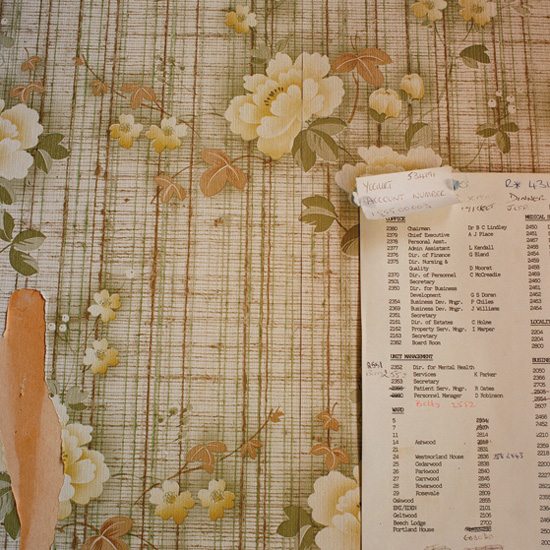

In this sense, while creating the images for the Black Dog series there were certain locations that became very relevant. So I returned to the hospital where I had been an outpatient, which was now closed down and derelict, but I obtained special permission to go in and photograph. The image making started to become about the intuitive sensibility of exploring places that had some kind of resonance in terms of my experience. For a long time during my illness I felt that I was part of some process and had ceased to be an individual. So certain kinds of things, signs on shelves that said ‘knickers’ or ‘pyjama tops’, became so relevant for me at that time when I felt like I was being processed.

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

I guess when I’m actually taking photographs I’m fumbling around looking for a way to interpret what’s in my head. I have learned that intuition is vitally important within my process, particularly at the image-making stage and it is this moment of recognition that brings the work together. As an example, during the process of production I often find I have ten almost identical images, yet something occurs in one of the images that make it come forward to correspond with what I was thinking. What this ‘something’ is will differ from image to image and so it is a case of knowing it when I see it. To quote Louis Pasteur ‘chance favours only the prepared mind’.2

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

Obviously, I want to present whatever I am attempting to say with some degree of coherence and for my work to resonate with others, so the audience is hugely important. The experience it brings to the viewing process often allows me to understand things I would never have recognised otherwise. I made a number of presentations as the work was developing, and the more I talked to people the more I realised that their experiences were very similar to mine. I discussed the work with psychiatrists and psychologists, with sufferers and their families, and what became apparent from this fieldwork and through my contextual research was the paradox that exists between the lived experience of mental illness for the sufferer, and the way such conditions are described or perceived by those on the outside, so to speak.

For example, we persist in using words to explain or interpret mental illness, which can often be difficult if not impossible to put into words. Whereas images allow us to go somewhere different, to express and communicate in alternative ways. When I have shown the work, for instance, I have had people in tears or saying that they understood for the first time what their husband, wife, son or daughter, friend or relative is going through or had gone through. And that is exactly what I wanted to achieve, to allow others to understand the experience of mental illness through my work, rather than it being specifically about my own experience.

The photograph helps to create an alternative vocabulary to explore mental illness, but I think you have to look at this as a journey using the images to create a beginning, middle and an end. I think a lot of photography works like that, it’s a medium that lends itself to storytelling, so that each image is linked to its neighbours like bricks in a wall. Nearly all of my projects are displayed as grids now (for example, 40 images become a block panel of 5 images by 8 images). I’m trying to relate one thing to another in a number of different ways so links or associations can be made diagonally as well as up and down, and all these different elements feed together to tell the story. If you take one image out of context it might address some sense of the subject, but the narrative breaks down and becomes meaningless. One image in that series cannot stand on its own, you may be able to see the signifiers, but for it to be relevant you need to see the whole sequence as story telling with a particularly visual narrative. I think this allows people to engage with the work on their own terms and in different ways, where they start or end on that particular grid becomes a personal choice. Two people looking at the same material might come up with completely different conclusions because how anyone interprets visual work is both fluid and personal.

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

In retrospect I learned a lot from undertaking my PhD as it allowed me to understand things that had been ticking away on an intuitive level, both from the things that I had read or things that I had experienced. I did come out of the process with a far more rigorous approach to my own practice than I had previously. I question things more now and that helps me to understand what I am dealing with in a deeper way on any given project, in contrast to what it was before.

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

So, for example, later projects including After Schwitters3 became primarily a means to allow me to explore my own preoccupations about the potential inherent within the medium of photography and to be far more than merely pictures of things.

I was very intrigued by the Schwitters story and this area of Lake District had been largely undeveloped since Schwitters’ death. Although Schwitters was the catalyst and the thread that ran through this particular journey. I chose to explore what interested me in the crumbling building and the contrast of objects both natural and manmade, and it pushed my photography in a direction that I had not taken it before. I think that to keep challenging what you do is hugely important as a practitioner. It’s that uncertainty hovering somewhere over your shoulder and kind of whispering in your ear—‘Are you sure this is right?’ What it boils down to is that for any work to be ‘right’ or, more accurately, relevant, it has to be informed, and the only way you can attempt to achieve that is by doing the groundwork.

Interview by Mike Simmons

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

From the series: A Black Dog Came Calling

Photography by John Darwell 1999–2003.

Notes

1 An Interview with Garry Winogrand from Visions and Images: American Photographers on Photography, Interviews with Photographers by Barbara Diamonstein, 1981–1982, New York: Rizoli. Accessible from: www.jnevins.com/garywinograndreading.htm.

2 Quote taken from Pasteur’s lecture to the Faculty of Sciences at Lille on 7 December 1854. René Vallery-Radot (1923). The Life of Pasteur. New York: Doubleday Page and Company, p. 79. Contemporary copies (2008) are available published by Bibliolife, Charleston, South Carolina.

3 This project grew out of an initial invitation to photograph the Cylinders Site in the English Lake District. This is where the German artist Kurt Schwitters started work on his project the MerzBau, which was left unfinished by his death in 1948. Schwitters (1887–1948) was a German Dadaist who originally created a Merzbau in Hanover between 1923 and 1936. This was destroyed in a bombing raid but an archive and reconstruction can be found in the Sprengel Museum in Hanover. Further information and links can be found here: www.merzbarn.net/hanovermerzbau.html.