Case Study

Judy Harrison

Judy Harrison’s work explores themes of visual narrative, personal histories, representation and social and cultural identity.

I READ THE PHRASE ‘you learn how to think’ in one of Edmund De Waal’s texts1 and I think that’s what creative practice is about. So many different approaches to research weave in and out of each other, often in oblique ways. It may be reading and seeing lines, groups of words and the spaces around these, which leads me to reflect, visualise images, processes and the interpretation and formation of my own words. Listening to a radio programme or going to a talk or a lecture can provide another space of connections and possibilities. It could involve visiting exhibitions, looking out of the window or having conversations and forming narratives. Research is about encountering new experiences, taking notes, meandering sideways and making sense of your own life and that of others. Research for me also involves an interaction with places and exploring the social landscape, whether that be the domestic, the industrial or rural, and how that can trigger my own experience, memories, meaning, imagination and interpretation.

Research is all those things to me. It is something that I am constantly doing. Having the time to think is important, to formalise this research and place elements into some sort of structure. Whether that’s in a sequence of images, a piece of text or a publication, different ways of thinking, diversions and tangents, experiences and methods shape these processes and outcomes of the research.

Often, things happen by intuition or chance and that’s a delight, but this may only happen by being open to seeing things differently, open to being taken on a journey. It’s about questioning what’s hap pening in the world, however large or small that may be, and how cultural and political situations have shaped our lives. I have always been interested in anthropologies, histories, cultures and communities and the contextual framework that they hang within. I worked on an oral history project on histories of migration with the Sikh community in Southampton over 20 years ago but the unresolved issues of migration, displacement and racism are as real now as they ever were.

I was brought up in a very political family; both my parents were members of the Communist Party. My father used to give me fireside chats about Marxism when I was about ten years old, so naturally I became politically aware from a young age. Although I didn’t understand half of it at the time it did resonate with me, and over the years I have come to realise how much and how often my early life, family background and my own life experiences have influenced my work.

When I look back, right from when I first started out in photography, key themes have threaded through my practice. I have always been interested in people and communities who have been marginalised in some way and the context that may have brought that about. The research into that is, first and foremost, about communication. Talking to people and learning about the social, cultural, religious and political dimensions of their lives are the things that interest me and feed into my work.

I don’t see photography as being just one thing or being separate from the world around it. Nor do I see my work purely on a visual basis or belonging to a particular style or genre, I’m interested in it connecting and crossing over with lots of other things, working within a wider critical framework. I like words and lines of words and writing is now becoming intertwined with my photography. I also want people to interact with my work and to collaborate with it in some way. The work has to have some connection and context with other people’s lives as well as my own. But when working with photographs, I see them as documentary fictions. That’s what interests me—the overlaps and spaces between fact and fiction.

I tend not to work in an over-planned way and I don’t often go into a new project with a specific plan or approach—I don’t work in that way at all. I obviously have a broad plan and do as much preliminary research as possible but I consider myself an explorer and often feed on chance. For me it’s more to do with chance encounters and experiences that actually bring out the results perhaps more than the chance encounters in the camera, and that’s how the farm project happened. I started the Small Farms in Staffordshire project while I was studying for an MA at the Royal College of Art (RCA), and I carried on working on the body of work for a number of years after that.

From the series: Small Farms in Staffordshire

Photography by Judy Harrison, 1976

I grew up in Stoke-on-Trent, in a landscape where industry ran in parallel and intermeshed with wilderness and nature. Pot banks, slag heaps and mine shafts edged onto farm land and beyond, and opened up into the grit stone hills and contrast of the Peak District. It’s a place I go back to a lot and still feel very much part of, a place where I belong. Small Farms in Staffordshire was based in the Peak District, and I worked within an approximate twenty-mile boundary between Leek and Buxton, crossing the boundaries and edge lands of the undervalued landscape of the Staffordshire moorlands and Derbyshire dales. It’s an area of harsh, often barren landscape with sparsely located small holdings, and farmers, who at that time, were struggling to make a living.

From the series: Small Farms in Staffordshire

Photography by Judy Harrison, 1976

I walked through the hills and moorlands, walked miles and miles with my camera equipment and began meeting people. I would meet farmers and listen to their stories and then one farmer would recommend me to the next farmer or I would pass somewhere and knock on doors and ask people if I could photograph them, but often I didn’t do this straight away. Getting to know people and building mutual respect before I introduce the camera is hugely important for me. It often results in more interesting and in-depth work; it is about how I get to something, what I reveal and the form that I use.

There were many unmarried women who were either on their own, sisters, or living with one surviving parent. They ran these farms in a stoic, strong manner maintaining their independence, often in isolation. I was interested in the vernacular and the banal, the spaces of the rooms, the objects and a way of living that was fast disappearing elsewhere. But here time seemed to have stood still. I took slow, studied formal portraits of them, of the everyday and photographed their cupboards and fireplaces, and drank cups of tea and returned again and again with more photographs to give them. I took contact sheets to show them and involved them in the process of choice. I wanted them to see the results as soon as was possible. This is an important part of collaborative portraiture for me.

Some of the farms were cut off so I walked for miles with cameras and tripods through rain, wind and snow. I studied detailed Ordnance Survey maps and the formalities of mapping, listened carefully to weather forecasts and researched the local topography and histories of the spaces. We sometimes wrote letters to each other and they told me about the weather and narrated events and fleeting moments of the day. I was very much influenced by the work of James Agee and Walker Evans, August Sander and Josef Koudelka at the time and all of this practical research and way of working influenced my later work.

From the series: Small Farms in Staffordshire

Photography by Judy Harrison, 1976

I worked on the farms project for a significant length of time and found it quite difficult to bring it to closure. I think it was only exhibition deadlines that forced me to do that. I like spending time on a project, reflecting, researching, developing and refining what I’m producing. There seems to be a process at work that builds momentum, often in a very organic way. It’s evolutionary in that it is not fixed or rigid, which is an interesting aspect of the research process for me. When I look at my work more objectively and talk to other people about it, I can begin to see how things connect that perhaps I didn’t realise in the beginning. I suppose it’s the unconscious at play; I am always letting my mind wander and making connections from the most obscure elements. I became very good friends with a lot of the farmers and although the majority are no longer alive, I have returned to the actual sites of the farms to see how things have changed and, most are still standing, although some are now unrecognisable. I go back regularly to the area and have always felt a real affinity and relationship with this landscape, the dialect and sense of place and, strangely, feel it’s where I belong. I was very guarded about publishing the images, becoming very protective of the pictures partly because the images were intimate encounters with people and place, although no one in the images objected to me exhibiting or publishing them. The Victoria & Albert Museum in London bought ten of the photographs for their photographic collection.

From the series: Small Farms in Staffordshire

Photography by Judy Harrison, 1976

I am interested in the use of collective, universal memory and asking questions about power and control. I read all the time, both fiction and non-fiction, from photographic books to essays and use writing in conjunction with my photographs. For example, Threads (2010) and Wedlock (2011) are two autobiographical pieces, and are part of an ongoing body of work based around personal memory. The way things stay lodged in the mind and how we fabricate things out of our memories interests me. Memory is a kind of fiction and photographs, no matter how objective we set out to make them, are constructs. The stories we tell are fabrications too, but it’s the bringing together of these facts and fictions and the connection between them, which help us to make sense of things. It was liberating to work on various projects that weren’t wholly photographic, with no new photographs made. Writing took over and at first I wrote extensively from the photographic images and memories. I edited the texts and stripped them back to their bare minimum, to a level of stark rawness.

From: Rejection (installation)

Photography by Judy Harrison, 2011

Addressing the inherent problems of representation is hugely important in all my work and is what I reflect on again and again. Growing up through the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s shaped how many photographers thought and worked, how we questioned what we were doing as documentary photographers, holding debates on representation and the recognition that it is a political issue. It didn’t come from our photographic education, it came, I suppose, through certain theorists, writers and photographic practitioners. It came as well from our experience of a particular time and place and our reactions to the years of political control and repression at the time.

From: Wedlock (installation)

Photography by Judy Harrison, 2011

During those years whole working class communities were stripped, robbed I would say, of their working lives and culture, their sense of place and community. Heavy industries like mining and steel were lost in Stoke-on-Trent, where I grew up, and no money has been put back into that city, just a dual carriageway slicing through the neglected waste of the six towns. It’s full of beautiful crumbling civic buildings, abandoned factories, pot banks and bottle kilns standing like ruins and ghosts in a void, which was once home to generations of skilled pottery workers who made and created world-class ceramic collections. I do a lot of reading on ceramics and have spent years researching the history of Wedgwood and the pottery pioneers and philanthropists and it’s an area of study I want to take further and to make more work on.

From: The Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop

Photography by Sukhdev Singh Roath, n.d.

But this isn’t about nostalgia, it’s about respect, dignity and pride. Rejection (2011) is the title of an archival installation that addresses these issues. It brings together, in a constructed setting, pieces of beautiful ceramic domestic cream and white tableware made in Stoke-on-Trent and classed as rejects after their first glaze firing, with each piece containing a blemish, mark or craze that I had collected over many years from factory shop skips. The room was painted very dark grey, almost black, with shelves to resemble a museum space. The materiality of the form, contours and physicality of the surfaces, lit by artificial lights, makes reference to that of a forgotten world. To me, it looked like a black and white photograph, resembling the tonal range inherent in that medium.

Narratives are suggested that may link the objects together but the new layer of meaning suggests a craft that had once been, which is no longer there. Both elements engage with my response to the rapid decline of the pottery industry in Stoke-on-Trent, so this piece came out of two different strands of my life, and research I didn’t recognise as research until I started work on Rejection many years later. It was also led by exploring new research on ceramics and photography in relation to the object, archives and memory. I have been influenced by the writings of Walter Benjamin, W.G. Sebald, Gaston Bachelard and Brian Dillon’s In the Dark Room2 and am really enjoying exploring both the writings and ceramic installations of Edmund de Waal.

I feel that research within the scholarly world is considered as an objective process, but whatever research I do and the information I gather to inform the way I think and work is open to interpretation. I might start research from an objective point of view, but ultimately how I interpret things and how I edit and make decisions about whatever I am looking at or exploring is subjective; taking out what I need to take the work forward. And in that sense research is a continuous process in that it relates to the ongoing and continuous nature of creative practice, as the research for one project will overlap or feed into another project in some way. My recent book Our Faces Our Spaces3 is a good example of that because my initial idea, and the process of doing that book, progressed into a whole new research project in its own right. It became a collaboration between myself, the participants of the Workshop and the theorists who contributed to the publication. The Workshop’s main ethos was built upon collaborative practice and it was fitting that the development of the book took on the same process.

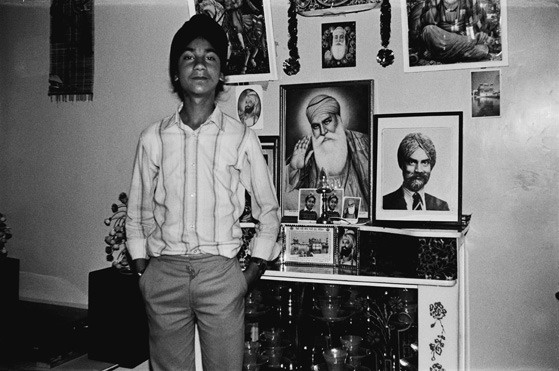

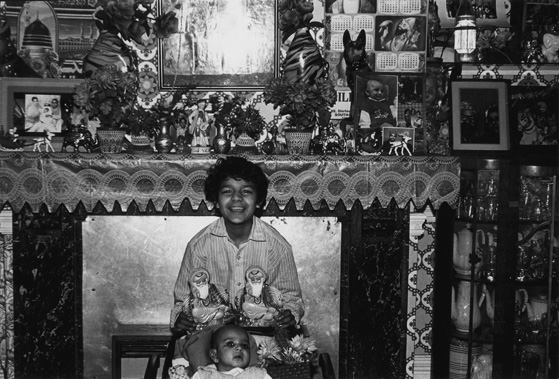

From: The Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop

Photography by Guljar Singh Pottiwal, n.d.

The book is a reflection on the Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop, which began in 1977 when I was awarded a two-year Arts Council Fellowship based at The Photographic Gallery at the University of Southampton. The remit was very open and the aim was to work with photography and children. I had to do a huge amount of research before I could start doing anything. Southampton was a new place for me and I didn’t know the area or any children. But, eventually, after significant practical research, I began working with Mount Pleasant Middle School in Southampton, which gave the project its name.

Around 97 per cent of the school’s intake was minority ethnic, predominantly Asian children and English was not their mother tongue. The teacher, to help deal with this, was making small basic reading books, and I immediately thought the illustrations could be replaced with photographs taken by the children. At the time there weren’t any books that addressed differences in culture and that’s what interested me, using photography with children for a purpose, in a context where it could actually be useful. When the fellowship finished I researched all sorts of ways to raise funding, and raised substantial amounts of capital and revenue funding, which enabled us to build a darkroom in the school and that’s when the Workshop began in earnest and grew into a large community photography project spanning thirty-six successful years.

From: The Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop

Photography by Balbir Kaur Pottiwal, n.d.

I left the RCA at a time when people were questioning the role of documentary photography, and I naturally became of part of that and began to attend discussions and meetings at Camerawork in London. But it was my involvement at the Workshop that actually gave me the practical context and theoretical framework to respond and develop my thinking in a far more pragmatic way. Working with the young people and their families taught me about the politics of representation and what that actually means. All this was research in a way for an ongoing philosophy for how I approached photography and contextualised my own practice. The boundaries of documentary practice have shifted and changed and I have responded to that, not only as a practitioner but also as a lecturer and teacher, wrestling and questioning and continually learning from working in collaboration with others.

I always saw photography as a fictional device and I could see how easily you can manipulate things, right from the start when I was a photography student at Manchester Polytechnic. Everything is subjective to a degree, it comes from reality but how you interpret things is wholly subjective. Confronting what we were doing as documentary photographers made us feel vulnerable and exposed, but times have moved on and I think documentary photography has changed and expanded beyond recognition and for the good. It’s overlapped now with so many other different disciplines and the whole ethos of research and critical thinking has fed into that. Documentary photography has a whole new momentum within much of contemporary photographic exhibited work. Digital technology has brought about a whole new ethos of people representing themselves, a commonality and sharing this with the public at large.

When the book project started a significant amount of time had passed since I had founded the Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop so there was a huge amount of material, and the starting point was editing and categorising to define certain areas that I wanted to look into or to take further. I found as many young people as I could who had taken part in the workshops, and I managed to find nearly everybody wherever they were in the UK.

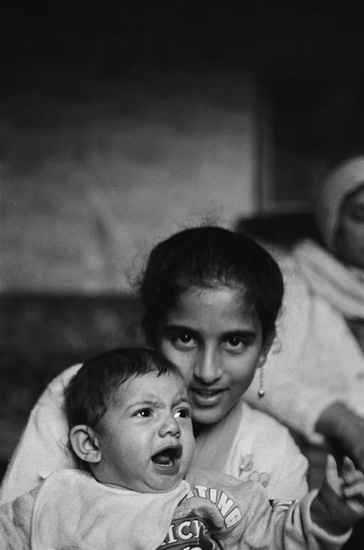

From: The Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop

Photography by Maryam Shafik, n.d.

Some people had stayed in Southampton but it was quite easy to track people who had moved away through their families and the arranged marriage system. Because of the depth of knowledge that I had gained about the Asian community in Southampton, particularly the Bhatra Sikhs4 and Muslims who were the main participants in the workshops, I was coming to the research process with the knowledge that I had gathered over the years about the community and the culture, by being part of it.

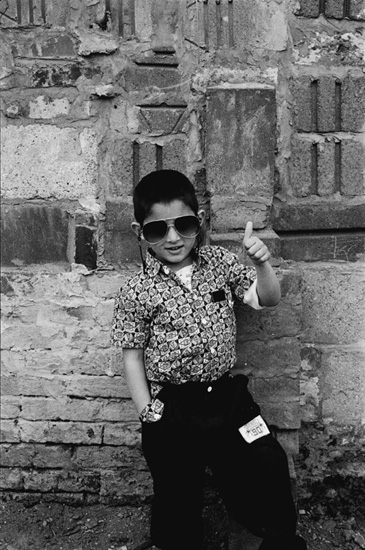

From: The Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop

Photography by Tanzeela Ali, n.d.

Once I had located everyone, contributors were either interviewed or wrote their own essays. They articulated their reflections and observations about the impact that photography had on their lives, and the confidence they had gained through making visual statements about representing themselves and their families, was stated with moving conviction and passion. Representing their social and cultural lives and their religions was important to them. From the racism that they had come up against at the time when they were youngsters in the 1970s and ‘80s, photography became a compass to navigate through and to challenge the politics of space. The ownership of the camera gave them a new confidence and freedom and became a ‘right-of-passage’ to reclaim the streets as a space which had previously been denied to them. The street as well as their homes became their studio.

The photographs the children created were used in the school for active learning, as language aids and tools for information and cultural expression. We produced a huge oral history project about the migration and history of the Bhatra Sikhs5 from the Punjab to Southampton and that took a huge amount of research over a few years. Parents gave the young people their old photographs to copy and we had started to amass a rich archive of generations of family portraits taken in Indian photography studios and it grew from that into an in-depth research project utilising local people’s archives. We collected stories from the many transcribed interviews we had done. The text in the exhibition was typeset in both Punjabi and English. The exhibition could be hired and from this it toured for many years all across the UK.

When you work with other people there is a huge responsibility to ensure that a balance is struck between your own interests and aims and that of the people you are working with. Becoming part of that community and working with different people of varying cultural backgrounds and religions was very important to me. I don’t think the Workshop would have worked if it had just been a short project. It was the longevity of the project that empowered young people and their families to use photography as a radical empowering tool for positive social change. I worked on the project as Director for 15 years but the Workshop itself was in existence for nearly 40 years.

In doing the book I wanted to reflect on the organic progression of the Workshop. I didn’t want it to be a historical account; I was interested in looking at it from the context of today, getting the young participants of the time to reflect and question if and how photography had impacted on their lives. I think the longevity and the political positioning it held is what made Mount Pleasant Photography Workshop unique and hold the value it has within the histories of photography. The trust, respect and collaborative integration took years to build. It was an important part of the children’s lives, part of their upbringing, and I grew up together with them because I was only in my mid-twenties when I started the project. I went to classes to learn Punjabi for a number of years and attempted to learn as much about the cultures and religion as I could. It became an important part of my life, it still is and I am grateful for that. What was interesting for me in producing the book was revisiting the work and finding out the strength of the impact on their lives and that fact that in producing the book, the participants picked up where they had left off. Research for me remains a collaborative two-way process and the research that I started as a young person has shaped and changed my life as much as it has the lives of the participants.

Interview by Mike Simmons

Notes

1 Edmund de Waal is a ceramicist, artist and writer. See page 220 in The White Road (2014) published by Chatto & Windus, London. See also The Hare with the Amber Eyes (2011) published by Vintage, London.

2 Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) was a German philosopher and cultural critic known particularly in photographic theory for his essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction first published in 1936. W.G. Sebald (1944–2001) was a German writer and academic. His writing often included photographs as a secondary narra tive to the text. Gaston Bachelard (1884–1962) was a French philosopher whose work The Poetics of Space is often found on photo graphy reading lists. He influenced many subsequent French philosophers such as Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida and Pierre Bourdieu who are often referred to in photographic theory. Brian Dillon is an English writer and critic and a tutor at the Royal College of Art whose writings cover, amongst other subjects, contemporary art.

3 The Bhatra Sikhs are the pioneer Sikh community to migrate to Britain. See: http://www.bhatra.co.uk/index.php

4 Our Faces, Our Spaces. Photography Community and Representation. Edited by Judy Harrison and published by John Hansard Gallery. 2013

5 See note 3