Case Study

Tom Hunter

Tom Hunter is a London based artist who photographs the people and places of his immediate community. He was the first photographer to show in the National Gallery.

MY WORK IS ABOUT COLLECTING stories, historical stories or contemporary stories, and reinterpreting them. I see research as having many functions but the main one is to provide background information. There is theory-based research—the ideas—and then there is the practical side. Some people separate those but I see them as interconnected. The product in my case is the exhibition, book or film. The research is everything I explore to come to that final result. Its influences, ideas, methodologies. It could be films, radio, TV, popular culture, literature.

Quite often, I don’t just produce the final image, I am making a lot of working images over what can be a sustained period. I think that as I keep on doing projects all this research gets mixed together and becomes an ongoing discussion with myself. Ideas keep on recurring and get added to. It’s a fluid process. Layers and layers of knowledge, information and influences get built up. They change, modify and mutate. When they mutate is when it gets most interesting.

In some ways my whole life is my research. I suddenly find that everything around me relates to what I am talking about and permeates it. You have to be tuned in to everything that is going on, not just your specific research, as I think that in some ways it is your job as an artist to be part of the zeitgeist. When an artist’s work works, it’s because lots of people are thinking about the same ideas at the same time.

I feel like I am a human library a lot of the time. I very rarely write things down. I used to but realised it doesn’t help me. If it is going to stay there, it will stay there. If I’ve got to write it down and keep referring to it, it means it’s not that interesting to me. The images that make an impression on me stay with me.

I keep on coming back to the same things; the same images, themes and motifs keep sparking things off. I’ve got a huge backlog of images in my mind, they stick with me and it can be years until there’s a story that reminds me of the picture that I saw by John Constable, or Velasquez, or Vermeer. Then I go back to look at the original again. I think about the image and how it would work.

Then I research the artist. I read biographies but mainly the history of the period and what was happening in the lifetimes of the great artists. Why was Caravaggio, for example, painting prostitutes from his neighbourhood as Madonna figures in a church? People may admire his work but not realise that what he was doing was incredibly radical in its time. Researching the history and context makes the painting come to life for me.

Many people think the interesting aspect of the picture is the aesthetics so they recreate it. To do this you have to have period costume, the same set-up and light. But it is a mimicking and has always seemed strange to me. When the great artists looked at a nude or a reclining figure they wouldn’t copy it. They would be thinking about what it was about the reclining figure, the form or religious meaning that was influencing them and how to make it their own.

The Vale of Rest from Life and Death in Hackney

© Tom Hunter

Anyone can copy a picture. But making it my own and talking about my life and times, my surroundings, the political climate and the things that are going on now is very important to me.

When I am researching these things I don’t see it as a job. It’s a pleasure. All the bits that I am most interested in just naturally sit there. Reading about Vermeer, or Caravaggio or Velasquez brings a whole picture to life and a whole backstory around it.

I see myself as having been an artist in residence in Hackney for nearly 30 years. I find everything connected with Hackney

interesting. Stories come to me in lots of different ways. The Hackney Gazette talks about stories every week. I very rarely cut them out anymore—they just stay in my head. Stories come from the pub, from tearooms, and now from the school playground where I pick up the kids and parents talk.

An important research theme for me is housing. I moved here and ended up in a squat because I couldn’t find or afford anywhere else to live. It was a desperate situation. It’s unstable housing and you can get kicked out at any minute.

I went to the National Gallery as a kid and one of the paintings that I’ve had in my head from childhood is of Adam and Eve in Paradise by Cranach.1 Cranach presents a world where there is no rent collector, no mortgage, no banks. It is a Garden of Eden and all you do is eat your apple under a tree and life is paradise. The theme of paradise runs through my work. When I left school I became a tree surgeon and worked for the Forestry Commission; I have always been fascinated by trees. They are the lungs of the planet and provide shelter, food, wood and materials for life. There is something incredibly symbolic about the Tree of Life. Hackney is an inner-city area but I’ve always tried to find my Garden of Eden here, looked for my little paradise in an aggressive, very urban environment, mostly concrete rather than mostly trees. The tree motif has brought a lot of nature into my work over the years.

Cranach’s image came back to me when I was involved in the A Palace for Us film project with the Serpentine Gallery. One of the participants in the project described the estate as ‘a palace’ to her when she first moved there from the slums in Shoreditch. But I was there when the estate was being pulled down and I saw the steel shutters going up to keep squatters and homeless people out.

Then, incredibly, in the middle of this estate there was this beautiful pear tree. The girl playing with her dog became everything that Cranach is talking about; the religious struggles in Northern Europe, the Protestant Reformation of Martin Luther, about Church corruption and about finding paradise and not getting confused by wealth and money. I wanted to bring in that concept of Adam and Eve and the apple that everyone has in their subconscious, but make it about London today and our young people.

This girl and her dog were there. There was very little to do. It was very simple. But that is because for 20 years I had been looking for that tree. All the research had already been done. I’d noticed this place two years before. The ivy was growing over the metal shutters and I saw this as a perfect spot to place someone. So I was just waiting for the right time to create that image, Woodberry Down.

I’ve got very clear ideas and that can make things easy and quite quick. So I did maybe 10 different images, slight variations. The dog moved slightly—it’s a slow shutter speed. I produce my images on a large-format camera; there is no flash.

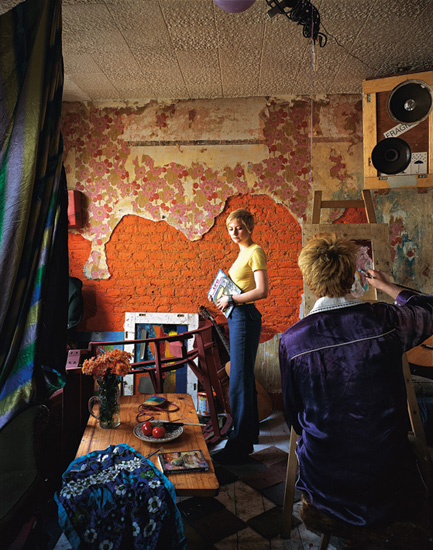

Death of Coltelli from Unheralded Stories

© Tom Hunter

But then I get to produce a large-scale photograph that has a presence, an aura like a painting in a church or a museum has. When Cranach made his picture, all he wanted was for people to just stay with it. I’m hoping for the same thing. It may just mean that the audience look at that picture for one second more and then move on. Whereas someone else will know Cranach’s painting and can unpack it. I’m hoping that it works on different levels and that there will be some new people who think, ‘There’s something interesting about this, what is it? Why has he done that?’ Then they might go onto my website, or read one of my books, which give more information about my work.

People argue about whether my work is documentary. A lot of my work is a document of what’s happening around me but I’m staging photography. I love that imaginary boundary between documentary and fiction. Where does one finish and the other start? I like to think that my work skirts around it.

Anchor and Hope from Unheralded Stories

© Tom Hunter

When you read people like Thomas Hardy his writing is the most clear, unflinching document of that time. But if you want a factual document you’d have to go to the parish records to read about births, marriages and deaths.

But what do you get from that? When you read about Tess of the d’Urbervilles or Jude the Obscure, you really get inside the mind and life of someone. You’re there. That’s what literature does so well.

I don’t think there is a clear division though every photograph is a document of a particular time. But people do believe the photograph, more than they believe Thomas Hardy’s writing. They think that writing must be fiction.

When people see my photograph they believe that is a real girl and a real place. And it is—when I took that photograph she did live there, that was her dog, that’s the tree on the estate, that’s where she played, those were her clothes. I’m not making it up or dressing her. But I did say ‘Do you mind just standing over there, that’s how I want to present you to the world?’ A documentary photographer would move around and change his perspective, whereas I move the subject.

It was the same with Ophelia.2 I saw that picture and it stayed with me. I got really interested in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, how they were talking about Victorian England and Britishness. I was thinking about how I could talk about beauty, about narrative, about the urban environment around me. A few months later a friend fell into the river after a rave party in Hackney Wick. I thought this was a contemporary narrative I could recreate. It’s not the Shakespearean narrative—it’s my Shakespearean narrative. Then it took me ages to find the location, work out what time the light came, then find the right person, time of day, clothes and when the flora and fauna were right, so that all the elements would be right when I pressed that trigger. The final image, The Way Home, took me 18 months.

Locations have never been a problem. Walking around, cycling, running, driving. It’s the landscape that I inhabit. I found a location before Christmas and it is still buzzing around my head. That could stay with me now for years until the right story or person comes along. Finding the right person is harder.

Research doesn’t stop when you take the picture. I process them and then often I don’t look for another week. Then I put them on a light box and leave them there, for months sometimes, to get a bit of distance. I go out to capture something with a clear idea of what I want to capture. So I press the button and come back with what I was looking for. But is that what I really want?

In Unheralded Stories, a series of Hackney stories, I found a location for the image Anchor and Hope.3 I took this girl there and said, ‘Let’s just try something very simple’. When I took the picture I didn’t think it had worked. But then I realised later that it had actually come together. There are lots of times when you create something really interesting. But you don’t know why, because it’s not what you wanted. It takes a while before you can recognise it. You can get too fixated on what you want and not what’s grown organically.

How to have a dialogue with your own images, how to look at, read and play with them, is a really important part of research. Let an image be, let it filter through and then look at it with fresh eyes. Painters do that. They let things build up.

But photographers don’t normally do that. During that time I think about the stories and what I am trying to say. What does this landscape mean? How does the body fit into it? What is the conversation between body and landscape?

The film project A Palace for Us involved a different kind of research. The first six months were spent visiting groups round Hackney to try and find a community I could work with. We ended up finding this amazing group of older residents on the Woodberry Down Estate who come together for a coffee morning every Wednesday. They were very vocal and passionate about the issues that were affecting them as their estate, which they had grown up on, was being transformed. They were being moved out and then back in. It was a huge upheaval for them and for the whole community.

I saw myself as a facilitator, rather than someone trying to document their lives. I spent six months going on day trips, having tea and chatting, and getting to know them. I decided to do oral histories. They had so much to say and no one was listening and I wanted to get some of this down before it was lost. I did about 30 oral histories in which they talked about their lives, how they came to the estate, and what it was like when they arrived. It was very much practical research rather than reading. It was learning from them—I got all my information from them.

The Serpentine Gallery was very supportive and helpful. All the stories came across as interesting, strong narratives. For me, the photograph gives you a narrative, but it always presents a lot of ambiguity, which is what I like about photography. But for the film I wasn’t looking for ambiguity but to get the stories heard.

The Unheralded Stories series is saying, wherever you live, it’s interesting. The deeper you go, the more interesting it is. You don’t need to go to Afghanistan to find war zones, or to Africa to find poverty. You don’t need to go travelling—there is everything in your neighbourhood.

I wanted to make a comment on the artists who, from Gauguin on, go to what they perceive as exotic cultures. I’d been looking at the painting, The Death of Sardanapalus, by Delacroix4 for a long time. It’s a painting that Jeff Wall and a lot of artists have looked at. But Jeff Wall has concentrated on the form and structure of the chaotic space. I thought about how it depicted a different culture as exotic.

The original painting is of a Sultan on his deathbed and a girl who is part of his harem and about to be killed. The Sultan is having his horses and everyone around him killed. It is an incredibly brutal scene. It is completely overpowering but I have always been drawn to this painting. I was most interested in the girl who is just there on the bed and completely tranquil. For

me, all the focus is on her. I started thinking about what makes this painting so interesting. What I have done in my picture, Death of Coltelli, is put just her in the scene and take out the narrative strand of the original. As a viewer you’ve got to imagine the whole scene around her. It becomes like a negative space, which is really important to me.

I was thinking about how I could do that in Hackney. Then at the café round the corner someone said the old lady who had owned the café had died and asked if I’d like to see her room, which was exactly as it was when she died. The café has been here since the 1930s. An Italian woman arrived and built this amazing Italian Catholic culture in Hackney, selling coffees, ice creams and pasta. I went upstairs and the room was a requiem to her culture and her life. In some ways that is what Hackney is about—the mixing of cultures. I don’t need to go to the Middle East. The cultures are right here.

In my picture the granddaughter is lying on her grandmother’s deathbed. It is a real deathbed. The stains are the fluids that get released when someone dies. There is all this religious iconography around. The image is about her Italian and Catholic past. The Italian granddaughter is the new English. She speaks with a Cockney accent. She has the Italian name Coltelli. I wanted to talk about contemporary Italian culture and contemporary English culture and how it’s changed.

Interestingly, this is now a Turkish kebab shop—which takes us back to the Middle East. That is what is so amazing about Hackney. It’s always been a place where immigrants have arrived. They have set up shop, brought their cultures, their food, their languages and integrated it into the life around them. They have made it an incredibly rich, diverse and dynamic place. But they have changed as well.

So it is a comment on multiculturalism. It’s a celebration and also a record of a simple life. Someone who came here, survived, made a life for herself and produced children and a granddaughter. It’s all about the granddaughter. I didn’t want it to be a death picture—it’s about life and death at the same time. Her eyes are very open and she is engaged with life. She is actually being born out of this. There is all this going on—but for some people it is just a picture of a girl on a bed.

I showed this picture at the National Gallery with the original painting by Delacroix, and with Jeff Wall’s picture. When you talk about ‘audience’, it was a dream come true to have my picture in that context, where people would spend a lot of time thinking about it in a place which is lit like a church. Having the original painting there you do take on all the religious iconography and symbolism in it. You do think about life and death and where you fit in. You think about the history of painting, how we paint our environment, how we talk about our neighbourhood, how we present ourselves and our culture.

The devil is in the detail. If I set this up in a studio—people pay a lot of money to get that right—the right wallpaper, the right bedspread. But in my picture everything is as it was. Nothing has been touched. I knew exactly how it would look. What I have done is just tiny little things like adding one light, which picks up the colour of her skin. I could have shot it in a studio. But for me having that link with reality gives it a whole other layer. It feels real. Lots of people I know—and they are great photographers—say they’d have photoshopped it or exaggerated one of the stains. You can change things and, to you, it looks better. But I think you actually lose the authenticity of it. You lose something that really connects. Years of research, taking and looking at pictures means I know what will and won’t work, but, of course, I get it wrong at times. And if I start overcomplicating things I lose the simplicity of the message and the amazing link with reality that photography has. So, my picture looks staged—and yes, it is—but it is that real person and real place. It is on that very edge of what is fiction and what is documentary.

Who you represent is a political thing. My work is about the ordinary people who actually live in a place. It is not about bringing in models to make these pictures better. I’ve been told how to make better pictures by lots of people over the years. But it’s the real body, not a manufactured body, and not the particular look of a model. It’s very important for me that I never use models or a studio. The reality of the place and the reality of people are very important. I do think all these people are beautiful.

There is a beauty in diversity. There is a beauty in the diversity of race, sex, gender, body size and I represent that. Unheralded Stories gives everyone a chance, gives ordinary people the chance to shine equally.

Interview by Jennifer Hurstfield; edited by Jennifer Hurstfield and Shirley Read

Notes

1 Adam and Eve by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1526, can be seen in the Courtauld Gallery, London.

2 Ophelia by John Everett Millais, 1851/2, can be seen at Tate Britain, London.

3 Unheralded Stories is a series of images depicting the folklore and myths that have built up around Tom Hunter’s community and surroundings in Hackney over the past twenty-five years.

4 The Death of Sardanapalus by Eugene Delacroix, 1827, can be seen in the Louvre, Paris.