Case Study

Ingrid Pollard

Ingrid Pollard is a photographer and media artist concerned with representation, race, difference and the materiality of lens-based media

MY WORK HAS ALWAYS HAD A research element to it but I don’t know that I ever call it that formally. It’s more like an area of interest that might carry me to look at some books, see a film, talk to people or travel to a, b or c as a start point. It encompasses a bit of everything. It depends on what I’m working towards and whether the end point is an exhibition or larger project or an ongoing line of enquiry.

Residencies, for instance, tend to be a useful research model. Sometimes a residency is a time for me to do research or just to follow up an idea but that’s rare. I’ve had 20 years of doing residencies of different type, place and duration. They offer travel, new situations and communication with people. Sometimes, a bit of running away from London. There are a different set of issues associated with each, but there’s seldom enough time for them to get really problematic. It can be a truncated and squashed time, three weeks, three months or a year. But there is a depth to the interactions.

The shorter residencies can be tougher unless I am familiar with the place or have been working there previously, when the residency can be a way of completing the research. I need the time. Having an end point, a means to disseminate the work, is always good for me. But, even so, the end of residencies is usually the time it feels like the moment to begin; even a year never feels enough time. Longer residencies do work better for me, being in a new situation and testing out and adding depth to ideas. It might also be about relationships formed, the geological interest of a new place and new materials to explore. The materials I explore and the place always have a direct relationship to each other, which runs through the work I’m doing.

The enduring issues that I return to are landscape and people and ideas of hidden histories—the interactions and the outcomes about how the landscape influences people’s behaviour and shapes the land through ownership, commerce, development, politics.

My work tends to be lens-based-photography, obviously, and through to video, print making or books—I maintain a commitment to the still image. Vision, light, the eye and how we see light and how we manipulate it—I can’t separate all that from the camera.

I undertake research that can be archival, literature, images or anthropology. Issues of black representation and black history continue to be central aspects. It is about investigation into the things that then make sense of the present, or provide us with different ways of translating the world. It’s also something about looking afresh at these things—combining sometimes incongruous elements that often don’t go together. I like the throwaway, the postcard as an authoritative voice, as the voice of the state, for instance. I work with things that are not usually valued, or given importance, like the unknown figure at the scene or the voice we’ll never know. You may have just one letter in the archive and I think it stands in for others that we will never be able to retrieve. The use of anecdotes in research, and for me as an artist, is valid because we’ll never know about those dark spaces or those dark matters of the unknown figures, they’ll always be shrouded. So, I make it up based on premise gained from research. Kim Hall, in her book Things of Darkness on research on Renaissance text and race,1 maintains that it’s feminist practice to do this type of insertion into history, because those are voices and lives that we won’t ever find, so it’s quite legitimate to fill them in by educated and reasoned guesswork.

Consider the Dark and the Light (2015). Camera obscura portraits (digital prints)

© Ingrid Pollard

Stuart Hall2 said to me ‘theory is just a tool’. A book could just have one phrase, one idea in it and this can be enough to hook me, to start a train of thought for me to work with. Just one phrase can be very, very rich, so sometimes it feels like that is enough to get a burst of thoughtful energy to go forward to do the hard work of research and practice of complexity.

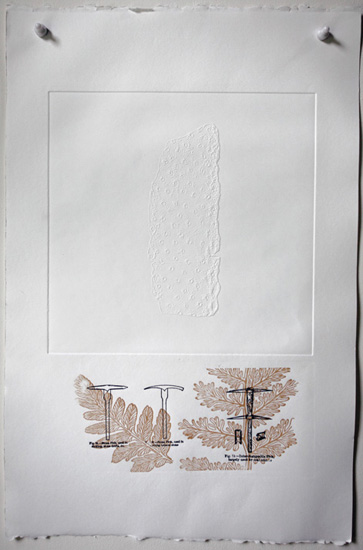

For example, I took part in a residency in Northumberland. I read books about the technical aspects of mining, books for mining apprentices that had quite a lot of instruction, what kind of pick they use for instance, identifying coal seams, complicated machinery, etc. I found fossils on walks through the local landscape and fossilised marks of a river and mud from the same period as the local coal seam. I made connections between form and geological features. I gained a basic understanding of coal being formed by the heat and compression of plants over many aeons of time, plants that I could see in the diagrams, beautiful illustration. There were also issues raised around rural economies, the people who worked the local farms, the historic monies and privilege gained through exploitation of natural resources. The form of my work, the real objects were reflections of the original apprenticeship books which I interpreted through making flick books. I used blind embossed prints as an expression of the pressures and events that went into the formation of coal. The important research took place in the Mining Institution in Newcastle with its

literature around mining and digging, geology and history below the surface.

Initially, these elements of reading, investigations into psychology, visiting galleries and history archives are all there, then I start to fine tune it into what I’m actually looking at and it gets honed down. But, in terms of looking at books, biography, landscape and geology and interrogating photographic processes, it is always something that motivates a line of inquiry, even when I’m not working on a project. I struggle with text and language and that’s always very important.

I am constantly trying to find someone who has made research into a form of practice, used it differently. For example the book I Send You This Cadmium Red,3 which is a correspondence between John Berger and John Christie, in which one might send a poem and the other reply with a painted yellow circle, it’s just refreshing.

There are ways that the labelling of me as ‘only’ a woman and a black artist has been imposed on the work I produce from the beginning. Circumstances meant I did film and video, which has formed the way I research, I think, starting with an empty space that is filled, filled with light, surface, the beginnings of a narrative, rather than blank canvas.

The making and the research are happening at the same time. When I first began making images for exhibitions it was more about pictures in frames on the wall, whether they were analogue, black and white, or light-boxes. Now they have many more different elements. With some works I can envision how it’s going to look from the start and how to achieve that—I know if it’s going to be wallpaper or it’s going to be a book. But how and why it is that form, is the thing that has to be worked on quite carefully for quite a long time and includes all those research elements, biography, literature. The end point is sometimes a matter of stopping; I get a deadline and have to stop because otherwise sometimes I’d just go on and on.

Analogue and digital are different tools and ways of working. I want to have as many tools as possible. Certainly, I use negatives. A lot of the time I’ll scan negatives I’ve produced using camera obscura recently, photographing the image that’s on the ground glass or on the viewing tabletops. So, form and tools are expressive implements, part of research, it’s always what does the job really. But I know whatever I do will eventually get scanned for publication and disseminated that way.

I’ve committed myself to the understanding of the photograph as evidence of research and as a research outcome for many decades. It is a type of research because it’s got particular elements that can be seen as theoretical research, which can be a set of concerns, a hypothesis, issues and questions, which have been resolved and the conclusion is the book or the exhibition. The differences

Regarding the Frame (2013). Print image (blind embossed and relief print) from digital source

© Ingrid Pollard

in my work as an exhibition, an installation, a book or portfolio don’t really reflect different research methods; it feels very obvious to me that they are all outcomes in various forms of the same research process I’ve described.

My practice involves the use of whatever tools are at hand and these different forms require that I acquire new skills, modes of enquiry and expression; that’s a major component, the continual breaking into new forms. For instance, when I was doing the residency in Northumberland I joined the ceilidh band, the choir, and took part in the Scottish dancing classes. These, in a strange way, felt like research, even though it was also fun and a way of getting to know people and about embedding myself in that community in a more structured way, too.

I did make photographs of the Scottish dancing and showed them as flick books; as a way to emphasise movement, it felt appropriate. But, then, I knew how to make flick books before, but I didn’t know how to do Scottish dancing or be part of a ceilidh band. There was a skill to be gained but I can’t divorce it from getting to know the people and being immersed and included in that community. So, the skills and the outcome and what I’m doing there are wholly linked.

I haven’t set out to ‘do research’ formally as an exercise; I tend to be following an interest, which can become a work, but I have set out on something and found it wasn’t going to go anywhere. It was a much earlier residency, which was also a type of commission. It was in those early heady days when digital was just starting for me, I remember it took hours to do complete layering in Photoshop; we had to leave it over night to complete the transformation. I didn’t know very much about the digital beyond transformation or manipulation and storage but it was a way to gain new skills that I wanted to learn. At the same time, the residency was an investigation of a particular location and the people who worked there during the summer season. But the three elements—the location, the new digital tools and their outcomes—were also obliged to fill the gallery’s three spaces. I found these could not work together for me. The elements of process, materials and practice and investigation and study were all too much of a mash in that moment and it was frustrating and torturous.

I do make recordings, use sketchpads, pens and pencils, scrapbooks, notebooks and cameras, which are all so lovely. I print pictures, though less now because it’s expensive. I do pin things up, print them; digital work can stay in the computer much longer so I tend to have fewer waste prints around.

I’m now doing a PhD by Publication and the requirement is to evaluate a body of my own work, commentating on my particular hypothesis, making conclusions about why those pieces of work constitute research and contribution to new knowledge. I have to draw out connections that they didn’t start out with. I think I’ve made it more difficult for myself by pulling out strands that connect quite a few pieces of work. If it was someone else’s work it would almost be easier, but looking at your own work—I’m the expert, I know so much about it, but I’m in the position of staying on track to answer the research questions only. I’m examining six bodies of work and picking out things that were important and how they were linked through ideas of migrancy, home and belonging. It’s something I can carry forward, learn and adapt, distilling ways of examining the work of others and student work.

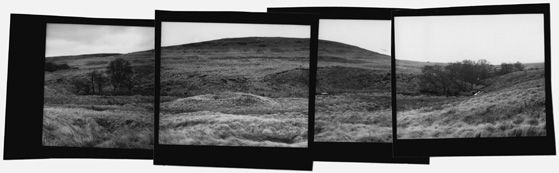

Regarding the Frame (2013). Collage digital print

© Ingrid Pollard

I’m always very interested in audience response and how my work is perceived; it can be the element in the dissemination of work you don’t always come in contact with. I can get critical responses and other forms of review, but often these take some time to filter through. That is also something that is different and useful about residencies. The local community can respond to what I do and the work produced very quickly; they’re also much more involved in it. They usually let you know what they think about what you’re doing. They may well be more familiar with that location than I am. I was told by someone from a residency that they like going to the artists’ exhibitions because they get to see what someone else, from outside the area, thinks of the place they live in, which is great. They tell you if they don’t like it as well, of course.

It can be slightly different with peers and the professional community being much more slippery in telling me what they think. It is usually really good friends who will properly tell you what they think; it feels like most people try not to. I find it just as difficult; I try to be honest and direct but it’s hard in way, which is different from a published review. I know how much people put into producing their work. But the response and evaluation of others is always important. I take some sort of validation and it is a marker that people do keep asking me to keep them informed of future works and events of mine. That’s one of the guideposts. But as Mark Sealy4 says, ‘You’re only as good as your last exhibition.’ The formation of relationships is as important as the political and cultural institutions that I’ve worked with over the years. These relationships that have formed, the moments that are shared over a long period of time, with artists or non-artists from the local communities that I am embedded in during residencies, can become genuine, long-term, friendships.

Regarding the Frame (2013). Digital print

© Ingrid Pollard

I do have a little mantra about research, which I say to students: ‘reflection, dialogue, question’. It means doing the work of making pictures. I include evaluation as part of the reflection. Do it, look at it and reflect on it and then do it again based on your reflection and research. I think that if you mention the word research to a lot of students they may become restricted by that, it becomes a thing that appears not connected to their practice at all. It’s a problematic word and students may think research can only be found in a book, or looked for online, but is not necessarily an activity they do quite naturally, such as talking to people, for instance, so I try not to use it or define it. You know, going to the cinema is research. I can see a lot of students who are already doing it, they just don’t know they are doing it, some are really incorporating research in their practice and it’s all mixed in together. It might include travelling or conversations or even playing the ukulele. I’m still waiting for my tango project.

Interview by Andrew Dewdney; edited by Shirley Read

Notes

1 Kim F. Hall (1995). Things of Darkness: Economics of Race and Gender in Early Modern England. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Press.

2 Stuart Hall (1932–2014) was an influential cultural theorist, writer, teacher and campaigner, and founder of The New Left Review.

3 John Berger (1999). I Send You This Cadmium Red: A correspondence between John Berger and John Christie. New York: ActarD Inc.

4 Mark Sealy, Director of Autograph ABP, www.autograph-abp.co.uk.