Case Study

Deborah Padfield

Deborah Padfield is a visual artist specialising in lens-based media and interdisciplinary practice and research within Fine Art and Medicine.

IF I THINK OF MY DEVELOPMENT as a photographer and artist, I would agree research has influenced my work in many different ways. However, I have found myself drawn into a more academic framework within the last 10 years or so, both working in a clinical context and completing a PhD at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where research, even when practice-led, is more formalised. But it didn’t start that way. My approach to research at the outset was a more natural organic process that I think most artists go through in exploring a particular subject they are drawn to. I began to realise, however, that there were some fascinating insights gained from working within other disciplines and in other environments. You have to take a step back to consider how you can explore these different perspectives and ap proaches within your own process, rather than trying to understand it through a process or discipline you don’t under stand—in a way, using the approaches of other disciplines to inspire and reveal but not to try to replicate or translate them directly.

It was during my BA studies at Middlesex University (as a mature student) that I became interested in pain as a subject. Prior to this, I had a career in the theatre but following a period of illness and chronic pain following poor surgery, I needed to find something less physically challenging and re-trained in fine art, in particular lens-based media. It was no accident that I was drawn to photography where something seen or imagined can be directly controlled or constructed by the photographer, which has relevance to visualising pain, which I will come back to. During my time at Middlesex a lot of the tutors were trying to get me to look at pain directly in my work, but at that point it was so close and so raw I didn’t want to or just couldn’t. There was none of the distance necessary to translate or transform it into anything that would resemble art, or that would be relevant to anyone else, so I made work about other things.

It was following an exchange visit to the Czech Republic with FAMU, the film and TV school in Prague, that things began to change. It was partly to do with arriving in an unfamiliar setting, with a language I couldn’t speak which forced me to look at everything afresh. I began photographing different institutions, from the Houses of Parliament to a hostel for the homeless and various hospitals. It was during that process I realised I was photographing something to do with isolation within different architectural spaces and that that had something to do with pain. It was from that point that I began to acknowledge what the subject of my photographs was, in a way that I hadn’t before. I was photographing the isolation of pain and/or the pain of isolation.

I began talking to my own pain clinician, Dr Charles Pither, then a consultant pain specialist at St Thomas’s Hospital in London and medical director of the INPUT Pain Unit there. He talked about the difficulty for patients in communicating their pain and with clinicians in understanding it. I was surprised to learn that pain’s incommunicability was as problematic for clinicians as it was for patients. Pain is a subjective experience but we often attempt to measure pain using objective methods such as the pain scale, where clinicians ask the patient to rate their pain on a scale of 1–10. Dr Pither described how he was interested in the way visual communication might create a bridge to the problem of describing pain more effectively. Using a body map he asked his patients to draw or mark the location of their pains. Some patients would draw on it, some would use different colours and others would go beyond the body map outline in an attempt to convey some sense of their pain through this visual method. I talked about how photography gave me a certain sense of control over what I was photographing, over the subject, which I was beginning to realise for me was reversing the sense of having no control or being out of control as a pain sufferer in a hospital. I began thinking about how that process might be useful for other people.

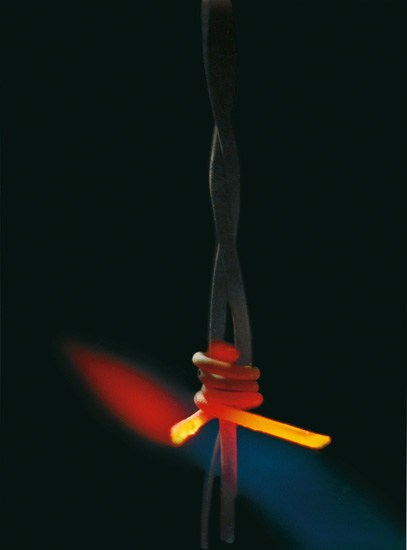

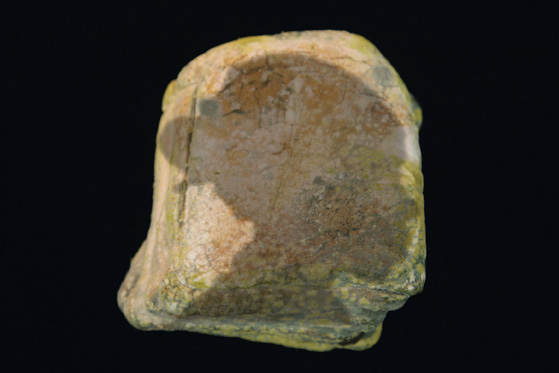

From the series: a stitch in …

Photography by Deborah Padfield, 2008.

It was through our conversations that the Perceptions of Pain project began to take shape and with a research grant from the Wellcome Trust’s Sciart programme.1 I began working with patients at INPUT with musculoskeletal pain to make photographs, which would help them communicate or open up different conversations with their clinicians or with their families about their pain. I was interested in the way images generate verbal dialogue, and how I could explore this in more depth. I came across research from academic disciplines very different to my own, and clinicians who were looking at the challenges of pain in very different ways via different methodologies and, in particular, the growth of interest in ‘narrative medicine’ as coined by Rita Charon. I started exploring whether it was possible to make something as invisible and intangible as pain visible and shareable and, if so, what type of language would this lead to. Would it be possible to co-create images with someone else, which reflected their experiences of pain. Could those images be useful in a clinical context and to other people suffering from pain or those caring for them? That’s what drew the project along and into more academic interpretations of research, but I still think it’s not entirely academic because it is a creative process, and somehow you have to try to keep that sort of intangible element in there.

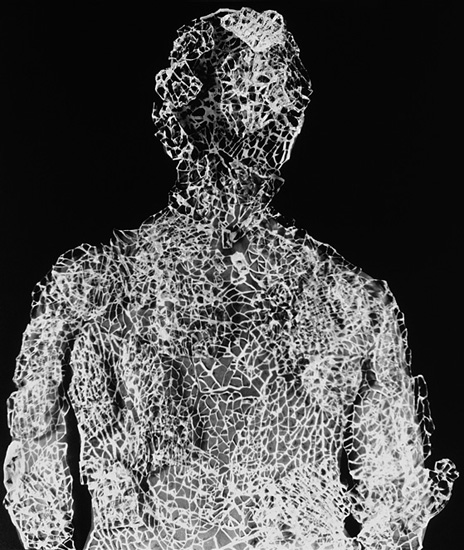

From the series: Fragile Boundaries.

Photography by Deborah Padfield, 2007–2008.

There is very little space in the methodologies and analysis of clinical research for individual insights or perceptions. Whereas in the creation of artwork, there is a lot of space for individual insight or observations, so there is a tension at the meeting of these processes. The challenge is to find a middle ground between those processes, a parallel perhaps with the tension between the patient’s and clinician’s perspective. If you come with different agendas and different bodies of knowledge, creating a mediating space through the interpretation of an image allows the tensions that exist to be unravelled and shared within that space, rather than straight across at one another. The photograph becomes a third or mediating space.

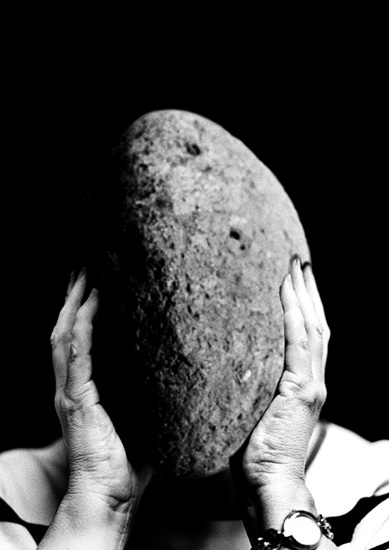

From the series: Fragile Boundaries.

Photography by Deborah Padfield, 2007–2008.

What is interesting is not only how images can facilitate an improved mutual understanding between clinician and patient, but also observing how photographs, in particular, or the conversations they generate can help us navigate other situations where there are two or more different perspectives. Here, the image can create a negotiated space, maybe a freer space, allowing the imagination or unconscious to work. It encourages a sensual response revealing other ways of knowing and understanding.

From the series: Perceptions of Pain.

Photography by Deborah Padfield with Nell Keddie, 2001–2006. Reproduced by kind permission of Dewi Lewis Publishing.

I think there are tensions for those working in creative disciplines where it isn’t always easy to evidence value, unless you adopt the methods or evaluation strategies of other disciplines. It feels sometimes as though you are always trying to do that in order to get published in a medical journal, or get more funding or pursue it in academia and the danger is that the very thing you offer as a creative practitioner gets lost. The value that creativity and creative practice brings is a quality that engages the senses, engages the unconscious, engages people’s own stories and associations, it engages the viewer’s responses to it, and I don’t want to pin that down, so part of me is still fighting for a way to stretch what is possible to publish within a medical or allied journal.

Research is a practical creative process. When I began working with patients at St Thomas’s, it seemed important that the patients I was working with were very much part of the process of creating the images. I felt if I came along and re-appropriated their experiences I’d just be re-presenting them in much the same way as their experience and identity had been re-appropriated numerous times during the diagnostic corridors. I felt the process of making images reflecting their experience had to be a collaborative one, but in that there is potential conflict.

There are aesthetic decisions you want to make and directions that the patients want it to go in, which you have to acknowledge and so it’s a constant negotiation between the two of you. Interestingly, it also leads the work in directions it would never have gone in without this collaborative process and the input and creativity of the pain sufferers I worked with. They forced me to work with new materials, for example, and I started using ice, moulding different body parts and making reliefs, which I filled with water and froze to make ice sculptures and photographing these as they dissolved. Some patients had talked about the dissolving and changing nature of their pain, as well as the literal sense of the coldness and texture of ice. Then there were other processes such as setting fire to various objects, learning how to make concrete (a common metaphor for pain experience) or printing on balloons or other surfaces with liquid emulsion. Because we were using purely analogue photography during Perceptions of Pain, there was nothing digital about it at all—the images were all physically manipulated in a very labour-intensive process. They were torn and stitched, and printed under different levels of glass in the darkroom and then reprinted and re-photographed with fragments of glass on top, so in the end they were quite complex. These were things I wouldn’t have gone to and aesthetics I would never have arrived at through my own process if together we hadn’t needed to suggest a certain sensation or a certain material quality in a particular way. There’s a real desire to have pain validated, and there is something validating about a photograph I think, more than any other medium. Because of the ‘authenticity’ we still ascribe to it, its apparent ability to document ‘reality’ it is the perfect medium for validating subjective reality.

From the series: Perceptions of Pain.

Photography by Deborah Padfield with Nell Keddie, 2001–2006. Reproduced by kind permission of Dewi Lewis Publishing.

From the series: Perceptions of Pain.

Photography by Deborah Padfield, 2001–2006. Reproduced by kind permission of Dewi Lewis Publishing.

A lot of the images ended up being quite surreal, which may have come from the influence of being in the Czech Republic and falling in love with the Czech surrealists and their photomontage. There are so many aspects of your life that end up influencing the work that you make but you don’t realise at the time. Equally, pain itself is surreal and the way you can depict it has to be through some surreal juxtaposition of objects or forms or through metaphor. David Biro claims pain can only be described metaphorically.2

I see collaboration as part of my research but it’s a specific part of the research.

From the series: Perceptions of Pain.

Photography by Deborah Padfield with Nell Keddie, 2001–2006. Reproduced by kind permission of Dewi Lewis Publishing.

From the series: Perceptions of Pain.

Photography by Deborah Padfield, 2001–2006. Reproduced by kind permission of Dewi Lewis Publishing.

From the series: Perceptions of Pain.

Photography by Deborah Padfield, 2001–2006. Reproduced by kind permission of Dewi Lewis Publishing.

I don’t think I really articulated it in the beginning as a co-creative process, it just became obvious when I was having discussions with people about their pain—they had the most amazing imaginations and range of metaphoric images for pain. The process we were both involved in was trying to make those tangible and put them onto a 2D plane, to make them sharable with other people. With everyone I worked with it was a different process, because they were different people, bringing different things. They wanted to work in different ways and I realised these were important negotiations. How we worked together never really became fixed. I think that’s why the images went in so many directions, ending up with a bank of images that somehow still have a sort of homogeny, I suppose inevitably because I was involved in all of them as some sort of constant, but they were also very varied reflecting each individual.

I have a very strong belief in the ability of images and the creative processes to help us share experiences and to understand each other. I think the co-creative process is the thing that probably has had more influence on my practice than anything else, and I have realised bit by bit that this has become part of my practice. I felt if I’m going to photograph other people or other people’s experiences they need to be recognised within that process, so that I’m not objectifying them and then again by extension being re-objectified by the viewer. I wanted them to have some control over the process. On the other hand, as a practising artist, I didn’t give them total control, or it would be their work. In the discussion with participants I told them I would retain the copyright but that they would always be credited as co-creators, if they wanted to be, and would be asked for their consent to show the images in public. Everyone, without exception, wanted to use his or her own name. It was important because it was a stamp of ownership and recognition of their experience and input. I also needed to recognise my own time and experience, I wasn’t going to take myself out completely, so it became very much a joint project.

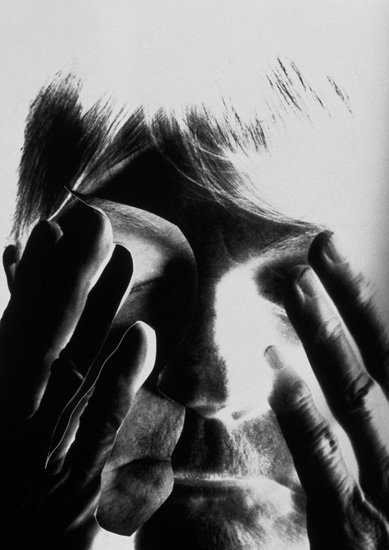

From the series: face2face.

Photography by Deborah Padfield with Alison Glenn, 2008–2013.

At the end of the Perceptions of Pain project some of the images were exhibited at St Thomas’ and Guy’s Hospitals, printed very large, before touring nationally funded by Arts Council England. It was courageous of people with that level of pain to be willing to have these large-scale images exhibited in their own hospital and beyond for other people to see. A lot of the patients said they wanted to exhibit them to take the stigma out of pain and others wanted people to start talking about pain and increase public awareness and understanding. There was a general feeling that maybe the response we got from the comments cards and from relatives and friends saying they understood pain experiences much better was valuable. Also that the conversations that developed generated by the images was equally valuable.

As a photographer or as an artist I cannot surpass what clinicians already do, and do brilliantly. All I can do is stretch the boundaries or suggest other ways of looking at something they are already looking at. I try to get the process away from a more reductive questioning and open up a broader type of dialogue that might still be relevant to have in a clinical space. The images appear to be a tool or a trigger for the patient to direct those conversations more, a space to be able to bring in things, which might be deemed less medical but are relevant to their experience of pain. The images create a space for sufferers to be able to describe the impact pain or its management has had on them and to have a space where they take control of the narrative in the consultation. Although welcomed by pain sufferers, I think at the moment it is still uncomfortable for some clinicians, even for those who are fascinated by and supportive of the work.

From the series: face2face.

Photography by Deborah Padfield with Alison Glenn, 2008–2013.

From the series: face2face.

Photography by Deborah Padfield with Alison Glenn, 2008–2013.

From the series: face2face.

Photography by Deborah Padfield with Alison Glenn, 2008–2013.

The face2face project was a development from Perceptions of Pain. I was again working collaboratively but this time with facial pain specialist Professor Joanna Zakrzewska and patients from the UK’s only specialist facial pain clinic at University College London, and later, running workshops in association with the National Portrait Gallery. The photographic images developed during the face2face project are now the subject of a multi-disciplinary project Pain: Speaking the Threshold where we are exploring the value of images and image-making processes in the diagnosis and management of chronic pain through different methods and lenses and have developed a resource of images or PAIN CARDS, which we are currently piloting for clinical use. We hope to make this more widely available once we have researched and understood its potential value. We have come together as a multi-disciplinary team, and I therefore imagined the type of dialogue we would have would expand and be quite multifaceted. The conversations have been rich, and as the process has developed, have in fact got richer and more complex but at the beginning I felt there was a dominance of medical language and a medical methodology—which we all allowed to happen. That is not to undermine those who bring that to the table as it allowed us to produce analyses that medical professionals would take seriously. However, I feel that the language of the arts and the insights of the arts find it more difficult to assert themselves. They are less fixed if you like, they’re more ambiguous and there is very little space for ambiguity in medicine and that worries me. I think the challenge is the risk of losing something quintessential about the creative process. I’m hoping that the images might help to promote a certain tolerance to ambiguity. I think it needs both clinicians and patients looking at the images not to be threatened by them and to not mind talking about them. Maybe there is a call for not just working with patients but also working with clinicians in handling or looking at images, exploring images together so they become more familiar and loss of control over the direction of conversation becomes less threatening.

Although there is a lot of discussion and a lot of funding available for interdisciplinary approaches and teams, there are few journals at the moment that will accept papers integrating rigorous quantitative scientific methods with the processes and values of the arts. It is paid lip service to, but actually if you go too far away from scientific methods the journals will not accept your paper. I think this presents a challenge to us as a team. Equally, there is clearly a solid desire from everyone in the team to make it work, and a vast amount of expertise available. So, despite some difficult conversations, a year and a half later we are still all meeting regularly, the analyses are being done by the different disciplines which will inform a final interdisciplinary paper and, for me, it is a really positive and exciting process. What is equally exciting is the distance we have all travelled. I feel this has influenced each other’s perceptions and we have all learned from each other. This would never have been possible by any one of us working on our own. The challenge of reaching medical as well as arts, photographic and academic audiences remains. The greatest challenge will probably be to get a multi-disciplinary analysis from multi-disciplinary perspectives into a medical journal, but we are trying. If we can do this I feel we will really have contributed to a shift in medical thinking.

To report the findings of this project to a medical audience, I have sometimes had to reduce the images back into numbers, (which carries a certain irony) because many medical journals will only accept quantitative papers. I would like to contribute to a movement to stretch the influence that the arts and humanities can have on existing medical practice because I feel sometimes the actual value that the image brings can get lost, particularly if we try to translate it or reduce it into something it isn’t and can only fall short of. I am hopeful that in the end, when we bring it all together, we could produce an interesting piece of work and a much richer one than I would ever have arrived at alone. It will also probably be more objective, as had I analysed the value of the images alone, it would have been an entirely subjective process. I think the sharing of our different approaches and exchange of methods and insights has benefited the work. The co-creative process has extended from the making of the photographs to the collaborative analysis of them and their potential to improve doctor–patient interaction and communication. It continues to enrich my work and understanding of the subjects I investigate. If we can use the tensions between disciplines as a source of creative energy and a fuel to more flexible understanding of complex subjects all of us benefit. However, in this desire we must not lose sight of toleration of ambiguity or of not knowing, which is an essential part of being human.

From the series: face2face.

Photography by Deborah Padfield with Yante, 2008–2013.

From the series: face2face.

Photography by Deborah Padfield with Yante, 2008–2013.

Interview by Mike Simmons

Notes

1 The Sciart programme was an initiative developed and funded by the Wellcome Trust, between 1996 and 2006, designed to support collaboration between the visual arts and scientific research, which has now been replaced by the Trusts Arts Award programme. Further information can be found here: www.wellcome.ac.uk/Funding/Public-engagement/Funding-schemes/Arts-Awards/index.htm.

2 Dr David Biro is an American dermatologist interested in ways to communicate pain more effectively. More about Dr Biro can be found here: www.davidbiro.com/index.html.