Shirley Read: Finding and Knowing—Thinking about Ideas

How important is it for an artist or photographer to find a subject matter that is particular to them? And what do we mean when we talk about the central concerns of a photographer’s work? What Simon Norfolk, in his interview for this book, describes in this way: ‘when I’m researching I’m still looking back fourteen years and thinking about the line that runs through and joins my work up’? Or in the same vein when Georgia O’Keefe in an interview, very many years ago now, said that looking back she could recognise that she had the same concerns in her nineties as she did when she was eighteen and just starting out?

As a curator I am looking for what is at the core of any work, whether it is the work of a student or an established exhibitor. What I am looking for will carry with it the sense that the work is powered by the authentic concerns of the photographer, that it is in some way heartfelt and has an integrity to its approach and treatment of its subject. For me, the presence of that authentic voice is what lifts a body of work above the everyday.

I once went to a photographers’ party where identifying the photographers from a set of anonymous images was a quiz set us for the evening. What helped us do this was not simply the photographers’ stylistic choices and habits—the use of particular framing, camera format, colour range, lighting or focal distance for instance—but the fact that, consciously or unconsciously, a photographer will usually have long-term preoccupations. These preoccupations may be in either abstract or quite material ideas or subject matter, an approach to the world or to making work.

So, for example, since the 1970s Peter Kennard has talked about war, armaments and poverty—and used a range of media including photomontage, painting, collage and sculptural installation to do so. In their interviews for this book Tom Hunter talks of his work as collecting and reinterpreting stories; Mandy Barker that ‘the motivation for my work is to raise awareness of plastic pollution in the world’s oceans and the harmful effect this has on marine life’; Ingrid Pollard of different projects being linked through ‘ideas of migrancy, home and belonging’; and Deborah Bright that ‘most of my landscape projects have to do with conquest and the obliteration of memory’.

The artist may, or may not, recognise their own motivation when they start out or may come to recognise it over time and across bodies of work: Simon Norfolk is known for his work on the landscapes of war and comments that

doing something about glaciers wasn’t a diversion from my usual interest in warfare but was, in fact, taking the core of that work and applying it elsewhere. That core is about time, the strata of time, photography as archaeology and archaeology as photography.

The Mariabad area, Pakistan

© Asef Ali Mohammad

Sian Bonnell also recognises how her interest has remained consistent while developing over time:

I realised recently that my central concern has remained the same since my earliest days as an art student. I was studying sculpture and I refused to make anything until I knew what space it was going to inhabit. I began making spaces that sculptures might occupy and it is only now I see that my work has revolved around defining Mohammad a sense of (often interior) space and then working out what the limits of this space might be through the placing of objects within it. The objects were often re-used and I came to see them as props. Only lately have I begun to enter the space myself—perhaps to find out what it feels like to inhabit it but this is an ongoing concern, yet to be resolved.

The parents of Nazir Hussain, a Hazara police officer, who was killed in a bomb blast in January 2013, holding his portrait.

© Asef Ali Mohammad

In some cases a subject matter is quite clearly a given, the result of background and circumstances. For example, Asef Ali Mohammad is a British-based Hazara, who was born in Afghanistan, grew up in Quetta, Pakistan and recently completed his MA in photography at Middlesex University in London. He is quite decided that his future lies in documenting the lives and struggle of his people. The Hazara are discriminated against as a religiously Shia and ethnically Turku-Mongol minority in Pakistan and elsewhere and as he says

I grew up with my parents talking about the Hazara’s struggle and so it was a natural subject for me when I started to train as a photographer. Whatever happens in my life I imagine that it will remain something I’ll always work on—because people still need to know about the lives and struggles of others. The Hazara are sometimes in the news when there’s a terrorist attack but I want to fill in the gaps in this picture.

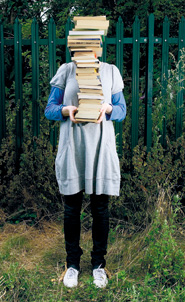

A subject matter may also come from a particular experience or time in the artist’s life. Georgina McNamara describes her interest in ‘the gulf between who we are and how we want to be perceived by others’ as stemming from the fact that:

As a child, I was uncomfortably shy. In my teens, I overcame my inhibitions by armouring myself with a bolder persona which in time became second nature. In earlier work, I focused on self-consciousness in self-portraiture, covering my face with a variety of props to enable myself to pose for the camera more comfortably. It can be hard to pinpoint why we are drawn to certain themes. For me, it was only when other students pointed out that all my work had a theme of hiding or disclosing that I was able to make the link between my teenage self and my ongoing photographic interests.

My current work revolves around ideas of revealing or concealment to explore how the mood of a person can be physically or metaphorically masked. Although I occasionally deviate from this theme, it repeatedly grabs my attention and pulls me back.

A particular approach to their subject matter may be the underlying concern that links different bodies of work from a photographer. So, for example, expedition photographer Martin Hartley acknowledges the influence of the early polar photographers on his work and says, ‘I think it’s irresponsible to travel on an expedition today and not gather some sort of data—because unless that’s what you’re doing it’s a holiday and not an expedition’.

Unicorn

© Georgina McNamara

Pile

© Georgina McNamara

A completely different approach is shared by Sian Bonnell and Grace Lau who both enjoy playing with aspects of image-making. Sian Bonnell remarks that she frequently explores what a tool or implement will do or what it’s not supposed to do by putting it to a different usage or context. Grace Lau says:

Issues about race and gender motivate my work because they are personal. Being Chinese I’m always aware of how people expect me to behave and speak. My instinct is to confuse their expectations so I make photographs which subvert rather than confront. But it was meeting and photographing people in the fetish and S&M sub culture, who played with socially accepted roles and encouraged me to document their role-playing, which led me to questioning cultural stereotypes in my own work. And this has remained a constant theme over the years.

So, finding one’s subject matter may take input or feedback from others and may also necessitate feeling one’s way through the process of making work. As writer and critic Geoff Dyer1 has pointed out, ‘You don’t have to know what kind of book you are writing till you have written a good deal of it, maybe not until you’ve finished it—maybe not even then. All that matters is that at some point the book generates a form and style uniquely appropriate to its own needs.’ I believe that this comment about writing holds good for photography.

The ‘not knowing’ can become knowing as we see from the intertwined processes of research and making work as described by Ingrid Pollard, Susan Derges and Hannah Collins, for example. The work may start from a few words, a feeling or question and be a process of discovery, a working towards something which feels right, true or authentic.

Deborah Bright adds to this sense that the interaction between knowledge and instinct cannot always be untangled but points out that the continued process of making work strengthens the artist’s ability to find their way: ‘Intuition is not random but channelled by my individual sensibility, a way of thinking and seeing that has evolved over many years of working behind the camera and making and looking at photographs.’ Or, as Edmund Clark says, when describing the moment of making a photograph, ‘the decision is related to all that research I’ve done before. Because you are having to work quickly you are so completely focused on what you are doing that you trust yourself to make the aesthetic judgement but also to make decisions based on what your brain is telling you is interesting.’

I do think that the recognition of their particular subject matter is crucial to the long-term progression of the work of any artist or photographer. That this recognition may take time and the accumulation of work. And that looking back at the concerns that form the backbone of the work and the interests which fuel it, with or without input from others, will serve to provide evidence of where they have been and point the direction for the future.

Note

1 The Write Way. The Guardian, 2011, www.theguardian.com/uk. Geoff Dyer is a writer, critic and journalist. He has written a number of novels as well as critical books including The Ongoing Moment (2005, New York: Random House inc).