Conohar Scott: Collaborative Working

Environmental Resistance: Art for change

The Rationale Behind Collaboration

My interest in the photographic documentation of industrial pollution first emerged almost by accident over a decade ago when I visited Eden, a small hamlet in Vermont, USA. My stay resulted in the documentation of Eden’s most notorious feature—the town’s abandoned asbestos mine. Once the largest of its kind in the USA, it was forced to close following a change in federal law in the late 1990s, which made it illegal to mine asbestos. However, no funds were allocated to cleaning up the site and the owner of the land was not obliged to take any action. As a result the mine remained as it was on the last day of production, with loading buckets laden with refined asbestos suspended in mid-air. I photographed the mine at Eden without having a clearly defined ethical stance towards the subject matter, and was simply photographing the mine as I discovered it. In doing so I conducted no protest, I appealed to no one and I maintained only a flawed objectivity without a coherent understanding as to what I was doing.

Following this realisation I undertook a project in collaboration with Greenpeace in Hungary. At the time Greenpeace were pursuing legal action with the EU’s European Commission. The action was against the Hungarian government for issuing a rather dubious licence to the waste disposal company TATAI. The licence allowed the processing of toxic waste from the production of aluminium at a plant in Almásfüzitö on the banks of the Danube. The highly caustic waste was stored in unsealed red mud ponds close to the river, which were susceptible to seismic fluctuations and represented a substantive environmental threat.

Behind the scenes Greenpeace supplied me with scientific data, maps, advice on how to enter the compound, and most importantly the contents of the licence. This formed the basis for the textual information that accompanied the photographs that I took at the Almásfüzitö site. The final project is composed of ten diptychs in which the photographs are juxtaposed with text panels that detail the entirety of the TATAI licence, which is breathtaking in its scope and permitted TATAI to dump any kind of industrial waste into the unsealed basin of the Almásfüzitö red mud ponds.

Asbestos Loading Bucket. From the series The Edge of Eden.

Photography by Conohar Scott, 2006.

The final outcome—Almásfüzitö: An Index—was disseminated in the form of a photo book delivered to 20 individuals across the EU, who had some professional interest in the case. Some of the recipients represented the Hungarian government and others were EU ministers in neighbouring countries or environmental scientists who might be sympathetic to the protest. In such cases it was hoped that the publication would stimulate debate across a number of diverse professional communities around Europe.

Although the book format was a successful means of highlighting the environmental problems ongoing in this location, certain difficulties arose due to my informal partnership with Greenpeace, which had a clearly defined operational structure and my position as an independent artist unaffiliated to the organisation. When it came to disseminating the photo book the campaign managers at Greenpeace were unable to back my project publically because Greenpeace were operating their own PR strategy. As a result, it would have been easier to sell Greenpeace photographs of the TATAI plant as a photojournalist might do rather than to provide the organisation with a conceptualised artwork.

Untitled Diptych. From: Almásfüzitö: An Index. Conohar Scott/Environmental Resistance, 2012.

Designing for Advocacy

As a photographer interested in documenting industrial pollution, I had to develop a method of working in order to situate my photographs into a cultural context where the photographs could contribute to an advocacy process, and be instrumental in instigating environmental remediation alongside the environmental science community or activist groups. It was from this aspiration that Environmental Resistance was born, which can be described as an artistled group that benefits from the diverse skills of its members. So far, it has comprised a photographer, an environmental scientist, a graphic designer and a translator/interpreter.

Importantly, working within the collaborative structure had the advantage of helping to constitute a group identity, which in turn led to the development of a mission statement in which a series of ethical and political objectives could be clearly defined.1

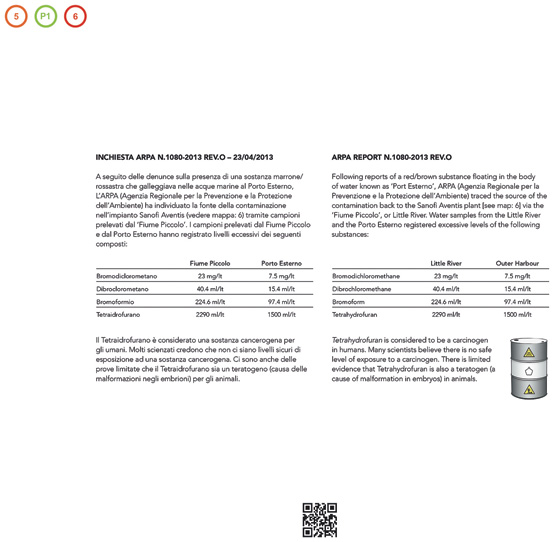

The process of designing for visual information advocacy—a term that sums up how Nongovernmental organisations employ imagery in order to garner public support—involves situating the photograph within a multimodal context, whereby additional information such as infographs, maps, QR codes linking to scientific data or activist web content, etc. can be displayed alongside or in combination with the photograph. The inclusion of additional modes has the function of anchoring meaning into the photograph by providing the audience with an awareness of the environmental or social problems relevant to a given location.

The importance that captions or additional modal forms play in connoting political meaning to the photograph is demonstrated in the most recent Environmental Resistance publication, No Al Carbone, Brindisi. The project was conducted in partnership with the Italian activist group No Al Carbone (NAC), which means ‘No to Coal’. The group has been active in their hometown of Brindisi, Southern Italy, for a number of years, and can muster a membership in the low hundreds for significant events such as large street protests. The organisation very successfully raises local awareness of the health problems associated with the four coal-fired power stations and various petrochemical works, which constitute the nearby Brindisi Industrial Zone. Our collaboration was intended to provide the NAC activists with a physical photo book, a digital file and website content, which could be used as a ‘toolkit’ for engaging in advocacy debates with public or state officials in the Brindisi region.

In the No Al Carbone, Brindisi publication, meaning in the images is anchored to a series of captions alluding to various scientific studies, which point towards Brindisi having elevated rates of cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congenital birth defects, when compared with other regions in Italy and beyond. Importantly, the project was designed to be an interactive publication, wherein the scientific claims stated in the captions are affirmed by the use of QR codes at the bottom of the page, which point the reader to a URL, allowing the audience to access the articles in full. This feature of the artwork was instrumental in altering the status of the reader from an initial position of passivity to that of an active researcher. In the context of the ongoing political situation in Brindisi, one of the aims behind the publication was to raise awareness concerning the existence of scientific texts, in order to widen participation in environmentalist discourse throughout the region and beyond.

Untitled Diptych. From the series: No Al Carbone, Brindisi. Conohar Scott/Environmental Resistance, 2014.

Mindful of the need to communicate with the inhabitants of Brindisi, whilst simultaneously raising the profile of a localised environmental struggle to non-Italian speakers further afield, it was important that No Al Carbone, Brindisi was written bilingually in English and Italian. Here, the contribution of a translator was critical. Our commitment to situating the photographs alongside a series of bilingual captions, detailing the substantive environmental health threat offered by the Brindisi industrial zone, is indicative of an overriding ethical obligation to communicate from a position of universal intellectual equality, as existent between all political subjects. For this reason, there is no ‘dumbing down’ of the content of the accompanying captions. Instead, there is an expectation that scientific knowledge pertaining to the sites of pollution should not be restricted to individuals who claim to have representative governance, or privileged professional access to information, at the advantage of the populace in general.

Future Directions

No Al Carbone, Brindisi provides a model of how collaborative working practices can provide a ‘service’ for localised activist struggles, by synthesising an indexical description of the Brindisi Industrial Zone with an overview of the environmental health implications, which have been suggested by a variety of scientific studies. In this way, an imaginative combination of art and scholarly research can be of benefit to activists who are intimate with the environmental problems that are impacting upon their community.

At the core of Environmental Resistance is the belief that situating the photograph in a multi-modal context can provide the public with new forms of knowledge and new ways of seeing and understanding a given locality. The individual can undergo a shift from a position of hitherto unknowing and invisibility to a form of citizenship that announces the visibility of the individual as an active democratic subject. It is art’s capacity to act as a framing tool for the dissemination of knowledge, which is capable of altering individual subjectivity and reconfiguring the social at a micro level, which represents art’s potential to act as a potent tool in the battle for political emancipatory struggles.

Note

1 For further details on the Environment Resistance mission statement and other works please visit the project website at: environmentalresistance.org