Mike Simmons: Documenting the Process

A Framework for Reflection

The scientific worker operates with symbols, words, and mathematical signs. The artist does his thinking in the very qualitative media he works in, and the terms lie so close to the object that he is producing that they merge directly into it.1

In contrasting the ‘two cultures’2 of science and art John Dewey highlights the unique and intimate relationship that develops between artist and subject through the creative process, where the reciprocal action of research and practice fold into one another. As a polar opposite to the scientific approach, Dewey’s observation also draws attention to the problematic nature of this symbiosis, as it can often be difficult to separate, value and exploit the things that emerge from within creative practices. In other words, when you focus closely on a project it can sometimes be difficult to ‘see the wood for the trees’.

Part of my role as an educator is to encourage students to step back from their work and to think critically about the relationship between their research and practice.

Central to this process is an objective examination of how the knowledge and understanding that emerges from the research process informs their practice and the key to this is reflection. This essay provides some theoretical and practical perspectives to help you develop your reflective skills and critical awareness.

The Project Narrative

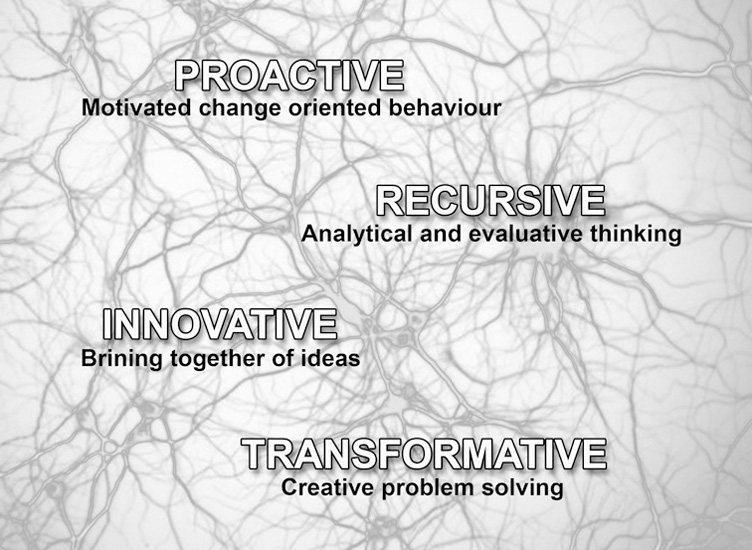

Photography first and foremost is not concerned with the concrete but feeds on the uncertainty inherent within the shifting borders of personal experience. Creativity is action orientated and driven by ‘doing’, a complex process that includes a range of research activities centred on information gathering. Doing can shift and change ideas through the development of knowledge, which as a photographer you will express through the ‘making’ of original artwork. As a method, each element seeps into the other to shape a personal journey of discovery that is proactive, recursive, innovative and transformative, and which provides an infrastructure that is bounded by context but remains open-ended and responsive to tacit knowing and intuition. It encourages rigour but embraces the notion of possibility where ambiguity and difference are familiar bedfellows. In this schematic representation the creative process is outlined as a fluid system of exchange, a holistic chain of events that crisscross and connect equally through and across multiple gateways to reveal opportunities and expose potential. This phenomenon has been described philosophically as ‘rhizomatic’, referencing the botanical term for plant growth with multiple connections and points for growth where ‘any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be’.3

Developed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, respectively a philosopher and psychiatrist. The concept of the rhizome is concerned with multiplicity and non–linearity.

However, to make personal visual statements relevant and to give them credibility, you need to take into account and question your own subjectivity and its relationship to knowledge and the potential for innovation. In order to survey the contextual landscape and navigate your way through the practical possibilities and keep sight of your purpose, the chart to steer by will be the detailed information recorded and reflected upon in your project narrative. Like the rhizome, which is a ‘map and not a tracing’,4 it will connect your research and practice in a number of ways. By engaging in a close examination of your ‘work in progress’ you will begin to question and test your ideas through the development of ‘critical distance’, a term used to describe the triangulation of ideas, research and practical experimentation. Being critical gives rise to an understanding of the connections, contradictions and challenges that you will encounter, and how this can change your perception through ‘the transformation of experience’.5

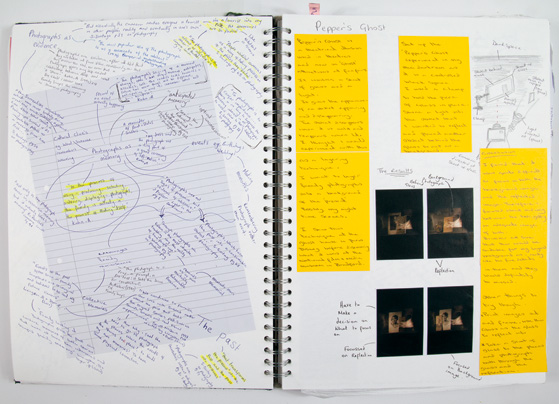

In this detail from the research log Shiam Wilcox, the project narrative combines contextual and practical research elements with reflective questioning and demonstrates the principle characteristics of the rhizome in action.

The key to reflection is the identification, analysis and evaluation of the implicit relationships embedded within your research and creative practice and making this tangible by documenting your processes and recording your responses in order to understand and exploit the things that emerge through doing and making.

Traditionally, in arts practice education this has been achieved through a research log of some kind. This can be a physical or digital notebook such as a diary or a blog, and can contain anything that is relevant to your creative work. Developing a project narrative is something that should form an integral part of your practice.

The scientific approach begins with a clear plan, question or design, but arts-based practice cannot have such a defined starting point. By engaging in the creative process you will begin to think and respond to the topic or situation of interest in the light of your developing understanding, which will change and evolve through the organic process of ‘doing’ and ‘making’ as you come to ‘see and understand in a different way’,6 questioning the what, why and how of your practice, you will begin to engage with the creative process on your own terms and in a way that is relevant to your own aims.

There are a number of established models for reflection that can be explored7 but a useful and straightforward approach for photographers (and adapted here) is the ‘What?’ framework for structured reflection.8 This model has three core questions that act as prompts for additional questioning. It builds logically, and if applied to each phase of a project, will inform each subsequent phase of work.

| Core question | Process | Characteristics | Additional questions |

|

|

|||

| What? | Describing the situation to establish perspective | Re-visiting the experience | What did you set out to do? What did you do? What were the outcomes? |

| So What? | Analysing the situation to understand context | Theory and knowledge building linking practice with research | What worked well? What didn’t work? What influenced my decisions? |

| Now What? | Evaluating the situation to modify future outcomes | Action orientated | What might I do differently? What other things do you need to consider? What might the consequences be? |

Adapted from Driscoll 1994 and Rolfe et al. 2001.

Reflection prompts interpretation and understanding in a number of ways and not only stimulates critical distance from your own practice, but it can also be applied to the work of others to examine a range of approaches, theories and contexts. Within photography there are many things that can happen in the process of developing a piece of work. For example, research materials are not fixed to one meaning and thus are open to interpretation, which can lead to unexpected discoveries. Photographers use a range of mechanical devices and processes that can at times have ‘a mind of their own’. Things can emerge thorough your practice that were not planned for and these chance encounters may be pivotal in shifting the direction of your work, which may become hidden or lost if not documented in some way, and an opportunity for development will be missed.

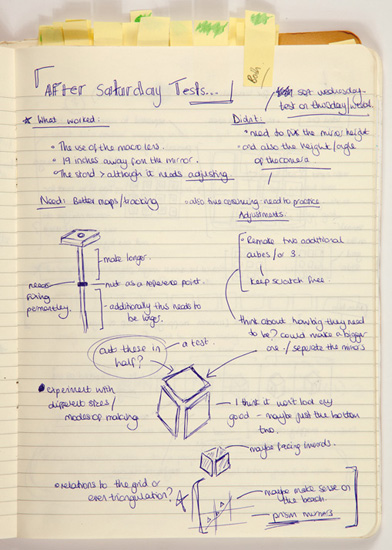

In this detail from the research log of Charlotte Fox, a review of a practical phase of work reveals a number of areas for further technical development.

Scholarly studies across different disciplines have acknowledged the existence and influences of intuition and chance, and there are many examples within the pages of this book that

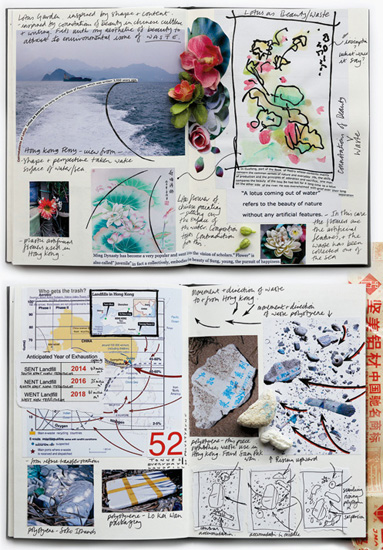

In this detail from the research log of Mandy Barker, the recording of practical and contextual information reveals the story behind the work. The information you record also becomes an archive and may take on new meanings through reflection to stimulate subsequent projects.

exemplify such events. But the literature has also identified that ‘an open and questioning mind’9 is required to identify and acknowledge such opportunities, which can be made explicit through the recording, reflection and evaluation of your activities.

You may become unrealistically attached to certain aspects in your work, which is another pitfall that documentation and reflection can identify and overcome. The questioning developed through your analysis and evaluation will allow you to make informed choices and keep focused on the purpose of our work. In any given project there are often challenges that may halt progress. The temptation is to alter your goals aims to fit the changing circumstances. But rather than simply sidestepping the problem, finding creative solutions is a far better approach and maintains the integrity in your work. Through your research log you can locate when the problem began, identify where things may have gone astray and why, and work through the problem and progress your work in a forward direction and improve your personal and creative performance.

Of all the research and practical experimentation you undertake, you will probably set aside more than half in the resolution of your work. But the choices of what to take forward and what to leave behind can only be made effectively if you know and are familiar with what you are dealing with, which can only be achieved through documentation and reflection.

Notes

1 See John Dewey’s Art as Experience. Originally published in 1934 but re-issued in 2009 by Perigee Books: New York.

2 C. P. Snow’s The Two Cultures was originally published in the New Statesman in 1956, and by Cambridge University Press in 1959. It is now in its eighteenth reprint.

3 For further discussion on the rhizome theory see: Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari (2005). A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia.Translation by Brian Massumi. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

4 See Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari as above.

5 David Kolb is an educational theorist whose book Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, from 1983, is available from Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

6 Clark Moustakas published Heuristic Research, Design, Methodology and Application in 1990, which is available from Sage Publications: London.

7 See Kolb’s Experiential Leaning Cycle, 1976. Also Graham Gibbs (1998). Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods; Christopher Johns (2006). Engaging Reflection in Practice—A Narrative Approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

8 Originally suggested by Terry Borton in his book Reach Touch and Teach: Student Concerns and Process Education, published in 1970 by McGraw-Hill: New York, and subsequently developed by Driscoll (1994), Reflective Practice for Practice. Senior Nurse, Vol.13 Jan/Feb. 47–50, and in Critical Reflection for Nursing and the Helping Professions: A User’s Guide, by Gary Rolfe, Dawn Freshwater, Melanie Jasper, published by Palgrave Macmillan, London in 2001.

9 See Pek Van Angle (1994) Anatomy of the Unsought Finding. Serendipity: Origin, History, Domains, Traditions, Appearances, Patterns and Programmability. In The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 45, No. 2 (Jun., 1994), pp. 631–648.