Case Study

Edmund Clark

Edmund Clark is a photographer working on issues raised by the war on terror.

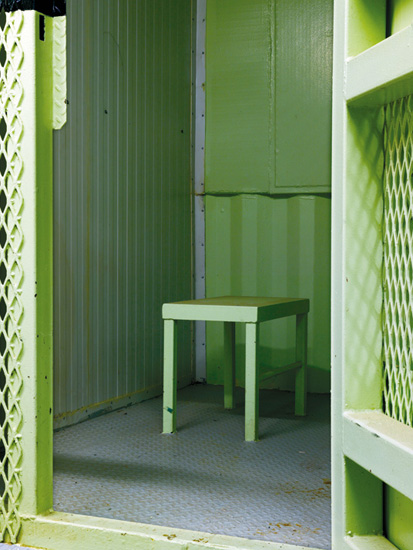

From the series Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out. Camp 4, arrow to Mecca and ring for ankle shackles

© Edmund Clark

FOR ME RESEARCH WORKS on many different levels and functions in many ways. It can be reading something specific about the background of a subject, an event or an issue. It can be talking to people who have been involved with that situation. It can be absorbing information, almost subconsciously, from the news or the radio. It can be anything from thinking about what kind of camera I am going to use to how I access a site or who I have to know to get access to a site. It’s everything.

My unconscious plays a part, there’s always something going on at the back of my mind about the questions I’m involved with, how they might be visualised and for whom. I’ve been reading a lot of Kafka recently and that’s directly related to the subjects I’ve been working on about processes of control. Looking for other cultural references, expressions and forms that relate to the ideas and subjects I’m dealing with is definitely a part of what I do.

The films I go to see are all related to my work. In looking at media narratives about things like extraordinary rendition, control orders and the way people who have been in Guantanamo Bay are perceived and represented the role of popular culture in helping to facilitate a changing common perception of standards of legality and morality is really interesting and important. Films like Zero Dark Thirty and TV series like 24 and Homeland are in some ways an expression of changing perceptions of standards of behaviour by our government agencies. But they also raise the question of whether they constitute justification or tacit agreement for some of the measures that these agencies have carried out. So understanding all that is definitely part of a wide research context.

The nature of the work I do in looking at the war on terror, the use of control and incarceration in that war and the expression of those controls through legal forms, whether it be memos justifying enhanced interrogation techniques by the American government or the formulation of control orders by the British government, means I have to really understand the legal implications. So, on Control Order House I worked incredibly closely with the lawyers at Gareth Peirce’s practice, Birnberg Peirce.1 They read every word I wrote. I had to know that what I was saying was watertight because I’d be an easy target if it wasn’t. And also I was producing material that could, in theory, be used as evidence in the case of the man I was working with, who was a terrorism suspect. In a sense what I was producing was also research in itself. I do think lawyers have both positive and negative attitudes to photography and are incredibly aware of what media exposure can bring to their work in terms of both public debate and possible damage.

There are certain starting points, such as access, with my projects. I think there’s a basic amount of research you have to do in order to know whether something is going to be practicable or what you have to do to find a way around the obstructions to accessing, representing or visualising something.

My work is actually about trying to visualise experiences that are unseen and the involvement of agencies in that—which is not something that photographers get to see. Yet I can use images in a way that will re-represent these subjects and through that try to engage people to think about them in a new way.

There are projects I’ve given up on because I thought they couldn’t be done. I was trying to do some work in Saudi Arabia, in a rehabilitation centre for ex-Jihadis and people who had been sent back from Guantanamo Bay. There’s a centre there where they use a mixture of western therapy techniques blended with what I think is basic intimidation and reward—if you do what you are supposed to do and you’re reformed you get a job, a car, a house and, I believe, a wife as well in some cases. I spent about a year trying to get access but eventually realised that, no matter what people said, it wasn’t going to happen.

From Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out. Camp 1, exercise cage

© Edmund Clark

For me, contextual research is more important than practical. I rarely have full control over the practical elements of my work because I am so dependent on getting access, dealing with censorship and with people allowing me to photograph or not photograph things or deleting my pictures or simply not being able to photograph something important. So my practical choices tend to be quite straightforward and a lot of what I do is shaped by the agencies I’ve got to deal with. I’ve just done a series of trips to sites around Europe, for example, including the former CIA black site in Bucharest.2 When photographing a Romanian government building, which I know they don’t want photographed, I’m unlikely to take a large format camera on a big tripod because I know I will get stopped. So in that kind of situation I will use a camera I know I can work with quickly but will still give me the quality I want.

From Guantanamo If the Light Goes Out. Camp 6

© Edmund Clark

So, practical research is shaped by the situation but that comes after I’ve developed my ideas about the project conceptually and considered how the form may allow me to explore other ideas about representation. These come out of the contextual research I do in reading and looking for documentation. I use a lot of documents in my work. How the bureaucracy of control looks is really interesting. The documents are the interface between power and the individual so how they look, how they’ve been presented or how they may have been redacted says so much.

From Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out. US Naval Base, McDonalds

© Edmund Clark

My research process is a constant process of absorption. I do a lot of primary research looking at documents produced by these situations and by the subjects and individuals involved and secondary research looking at how academics, journalists and lawyers have written about them. A lot of my research is down to personal contacts. Talking to people who have been the subject of extraordinary rendition or have been held in Guantanamo Bay or living with a man who is a terrorist suspect is a key part of what I do. There may be no people in my pictures but I have directly related to the individuals who are involved. I don’t interview people like a journalist would; I just spend time with them and let those relationships develop. So that aspect of personal contact, which I would define as being part of my research, is incredibly important.

From Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out. (top) Ex-detainee’s home (bottom) Ex-detainee’s home, rose suspended in solution

© Edmund Clark

The decision to re-read Kafka came out of an essay in book of literary critique, On Art and War and Terror by Professor Alex Danchev.3 I’d read Kafka a long time ago and with a different understanding. I’ve also looked at WG Sebald who uses photography, documents, direct memory and experience combined with a more fictional narrative. There’s a relationship between the way Sebald writes and uses images and documents and putting together photographs and documents about extraordinary rendition. Extraordinary rendition is all about obfuscation, cover-up and denial being in plain sight and this geo-political, moral event, which was the extra-legal abduction, detention and torture of people by the west. So, looking at the way a novelist like Sebald is using a range of different forms is really interesting in terms of how I think about how I am going to formulate my work.

My research is both random and comprehensive because it’s just implicit to the way I’m thinking. But, when I analyse what I’m doing, there’s actually something quite logical going on and, having worked as a researcher, I can recognise that I am accessing different forms of material from different sources. What’s so interesting about this, and perhaps why it’s so particularly relevant to photography, is that tension between the creative act and the informed decision. The form of my creative act is deeply informed by the research I have done. For a previous project I had, for instance, researched sixteenth-century Dutch Vanitas painting in which everyday objects were imbued with symbolism representing the ephemeral nature of temporal life. Because I had looked at that type of iconography, I could then see the rose and its petrification in a vase in the UK home of an ex-detainee as an image of confinement and abuse.

The obvious definition of the creative act for a photographer is when they’re looking through the viewfinder deciding what to put in the frame and when to push the shutter button. You can be working it out formally but you also kind of just know when the balance is there, when something is going to make an image that works. But the decision is related to all that research I’ve done before. Because you are having to work quickly you are so completely focused on what you are doing that you trust yourself to make the aesthetic judgement but also to make decisions based on what your brain is telling you is interesting. Sometimes you don’t know at that moment why that is interesting but you just know it is. So, for example, I walked into the McDonald’s on the US Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay, looked out of the window and saw a statue of Ronald McDonald in what looked like a cage. Everything about it spoke of a sense of confinement and complicity; even this smiling and waving symbol of the American way of life was confined. Perhaps I wouldn’t have seen this scene and recorded this image in this way if I hadn’t researched the history of the US naval base at Guantanamo since 1898. This meant I understood it represented a small town microcosm of America and a place of confinement in its own right since, after the Cuban Revolution in 1959, it has been cut off behind a razor wire fence and, for a while, an extensive minefield.

The other aspect of a creative act is that curatorial thing when my research takes me to a primary source who has put together a paper trail of evidence. That is an act that is in some way similar to the act of taking a photograph in as much as I’m looking for something which is, in terms of its evidential purpose, interesting and important and also has a visuality to it.

The Letters to Omar series, which are part of the Guantanamo work, were incredibly interesting documents.4 These are photocopies and scans of letters and messages sent to a man in Guantanamo. They’ve been produced by a number of different stages of intervention, redacted, stamped, archived and are images that have been created by the administrative process of Guantanamo Bay—they literally bear witness to degradation, they’ve been used in the control of the man they’ve been sent to, they’ve added to his paranoia and disorientation. I had researched the Camp Delta Standard Operating Procedures, which I found through Wikileaks, which described the Behaviour Management Plan: ‘The purpose of the Behaviour Management Plan is to enhance and exploit the disorientation and disorganization felt by a newly arrived detainee in the interrogation process. It concentrates on isolating the detainee and fostering dependence on his interrogator.’ In the same document I came across a matrix that listed what detainees could have and how they were treated according to five levels of compliance. Omar was at the ‘Intel’ level, the highest level, so everything was controlled by his interrogators, including whether, and in what form, he got any posted materials. This research directly enriched how I saw the significance of the letters and how they reflected the exercise of control and the experience of abuse at Guantanamo.

From Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out. Fellowship Room, US Naval Base

© Edmund Clark

Lastly, I think it’s the form. I no longer do conventional photography books, the books I do are about form. Whether it’s Control Order House, the Mountains of Majeed or the rendition work Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition, the form is important.5 The object, the way in which you envisage something is shaped by censorship and control and other forces. I can never know what I’m going to have by the end of the day so that process of reflection, refining and deciding the form is all part of the creative act.

In the case of Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out the work should evoke a sense of disorientation in the mind of the viewer and this is a testimony to the disorder which was central to the techniques of disorientation of Guantanamo.6 I aimed to do this by reconfiguring the creative potential of the images through the disjointed or disordered sequencing which mixes home, naval base and prison camps.

So I suppose what I do is a number of things—my research is constant and ongoing and feeds into a series of creative acts at different stages which take different forms right through from when I may first use a camera or choose a document to how something may look on a wall or in a book in five or six years time. They are all different stages of a creative act that are directly related to an ongoing absorption of information and ideas.

From Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out. Officers’ Mess, Tiki Bar, US Naval Base

© Edmund Clark

I came to photography late. I studied history not photography so, whereas some of the students I work with now have been through a process of learning cultural and critical theory, I never had that and in some ways I am quite envious of them. It’s a difficult one because I do come across work that is so critically driven that it is gasping for a life and so dry that it doesn’t engage at all. But at the same time I think that an awareness of where your work stands in relation to theory is really useful because it helps you understand what you are doing and put yourself in relation to the canon of work which has gone before and to what people are doing now. Researching that kind of material—whether it’s reading Foucault or talking to Professor Eyal Weizman of Goldsmiths, London University, who led me to reading Derrida, about the work he’s done on the visualisation involved in the forensic process and how that relates to ideas of aesthetics and art and the visual imagination—is a really useful way of feeding yourself with ideas that lead you to question and redefine what you are doing.

I think collaboration is important in evaluating the work. I’ve built up a group of people who I use as reference points. They are people whose opinion I trust, whether that’s the relationship I have with a designer or editor—there have been a number of cases when they have really brought something to my work—but also if I’m trying to explore an idea then being able to ask what someone else thinks and if they think I’ve got it right, that’s a form of research as well.

You always feel vulnerable when showing people unfinished work. But the creative act is a vulnerable act, you are exposing yourself. It’s also vain at some level we are all seeking affirmation for what we’ve done and that’s no different from being a singer, a writer, an actor. And you want it to be seen, you want it to be covered, to be engaged with so you feel vulnerable. But I am more confident about showing people work in progress than I would have been 15 years ago.

I don’t make a formal record of my work in progress. Digitisation has materially changed a lot of that, whereas before I might have been working with contact sheets, putting stuff in scrapbooks and writing notes the editing software is kind of replacing a lot of that materiality. The way you organise your files on a computer is a form of record, it records the date that every folder was created or image modified. That’s a kind of log should anyone decide to research it when I’m long gone.

What I do have is a box, which is partly a memory box, for each project into which stuff will go. Films and contact sheets, some bits of reading, objects like someone’s hat or something someone has given me and magazine features will go in there so it’s kind of creating a project archive but I’m not logging the research process as such. Certainly my bookshelves are a kind of log, a testament to areas of interest and research.

My aim as an artist is not to dictate opinion but to raise questions, to try to engage audiences and create space for them for reflection. I have to find a balance between explaining too much or too little. There are different audiences relating to different contexts, media and platforms. I try to present work accordingly. It is a balance between what I think is right and new or different in the way I want to explore a subject and considering how best to engage an audience with the subject matter.

Audience feedback is really important. When you let the work go and other people take control of it is, in some ways, the most liberating part of the process. That is when I have a sense of ownership about what I’ve done even though I’m letting it go and letting something have a life of its own. There are occasions when people say things about my work and I realise I hadn’t thought of that and that’s really exciting.

The way you talk and think about the work always changes and the way other people talk about it evolves and can impact on what I say. The way people are reacting to the work I did on Guantanamo Bay now is different to the way they reacted six months ago because we have heard so much more about that subject. I would definitely take an image out of an exhibition or change the order in response to feedback. I find exhibiting exciting because each time I’m invited to show the work reacts to the space, to the curator, to the gallery. It’s part of the fun.

There has to be a demarcation at the end of a project and that can be a difficult time psychologically because you’ve invested so much in something. But I revisit projects when I get asked to show them, and this body of work is kind of building, so when I come to exhibit the work on extraordinary rendition that will change how I revisit Guantanamo. It will be really exciting. I’m now in discussion with two museums about exhibiting several of my projects together as a body of work on one theme.

Of course, chance plays a role in this. But that’s like life—chance encounters, chance discovery, opportunity dropping your way to go with the foundation of work and research.

There is an overlap between researching different projects because, hopefully, I’ll have more than one project on the go. I put projects on hold for years because I know there’s something I still need to find out. There’s a multimedia piece about Pakistan and Afghanistan, I have visual and audio material from people I’ve met in Pakistan and from the internet and academic documents written by military people about ideas of ethics in war. The central core of this is about honour and sacrifice in warfare, which is a shared concept across many different cultures. In a way The Mountains of Majeed is about trying to create equivalence between an Afghan and a western point of view. This new body of work is the same, it comes from a line from an ode by Horace, ‘dulce et decorum est pro patria mori’ (it’s a sweet and honourable thing to die for one’s country), which was immortalised by

Wilfred Owen in the First World War when he used it for the title of a poem about gas attack. Today you’ll find it on the memorial arch in the Arlington National Cemetery in America. I worked with two poets in Peshawar to write a Pashto version of this poem. It’s a really interesting project, all based on research, but it’s been sitting there for about two years—it’s about finding the right form. I’ve just been asked to develop it for an exhibition in Dubai later this year and I need to find a multimedia expert who can understand what I’m trying to do and help visualise it. I can’t work out how to make it work.

I think I need to spend more time on my practical research because conceptually I’ve kind of reached a point in photography. I need to explore and research other forms and skills, other techniques and beyond photography. I use both film and digital but I’ve never used camera-less techniques—except I did try making photograms from a computer screen for the rendition work. It was technically too difficult because you couldn’t control the light. There are now things that are beyond any one person, like really good multimedia work, which would use people with experience in film and sound to augment what I am trying to explore.

The other aspect of research is the slightly prosaic stuff of getting your work out there, partly through that gradual process of developing a network of contacts but also thinking about who might be interested in your work, who might be the people to talk to, which galleries, which museums might be interested, that’s all part of research. It’s a Sisyphean task, as you go up you are always looking at people who have been working longer and you always think they’re established, they’ve done it. They probably don’t feel that. At what point is there a critical mass of awareness which starts to self-perpetuate without you having to do anything yourself?

Interview by Shirley Read

Notes

1 Control Order House (Here Press, London, 2013) is available from www.herepress.org/publications.

2 A black site is a military term for a location at which an unacknowledged black project is conducted. It has been used to describe the secret detention centres operated by the CIA in the War on Terror.

3 Alex Danchev (2009). On Art and War and Terror. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

4 Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out (Dewi Lewis Publishing, Stockport, 2010) is available from www.dewilewispublishing.com.

5 Control Order House (Here Press, London, 2013, 2016) and the Mountains of Majeed (Here Press, London, 2014) are available from www.herepress.org/publications. Negative Publicity: Artefacts of Extraordinary Rendition (Aperture/Magnum Foundation, New York, 2016) is available from www.aperture.org

6 Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out (Dewi Lewis Publishing, Stockport, 2010) is available from www.dewilewispublishing.com.