Case Study

Hannah Collins

Hannah Collins is an artist and filmmaker whose work engages with the collective experience of memory, history and the everyday in the modern world.

RESEARCH IS NOT ONE constant thing for me; it morphs into different things at different times and on different projects. I think that my work starts from an initial feeling about a subject or about what might be expressed through a project and in the process of developing it the research becomes the project. But for this to happen the research needs to be there in the first place. So I would say that, for me, research and the final output are very intertwined but I’m sure that would be true for everybody.

I think it works better when it’s something that expands and develops rather than an idea that is complete and just needs to be executed. Phase one tends to be a very general interest in something, which starts me thinking about it. It’s sometimes ten years before I do anything about it. Phase two is intensively wanting to know more and trying to find the information, then working out what to do if I can’t find it. Phase three is putting the interest and research into some sort of action.

A key thing to researching is also that it’s a very different world to the one before the internet existed. Everyone has access to so much information yet I don’t know if it fundamentally alters what art looks like because nothing replaces on the spot research.

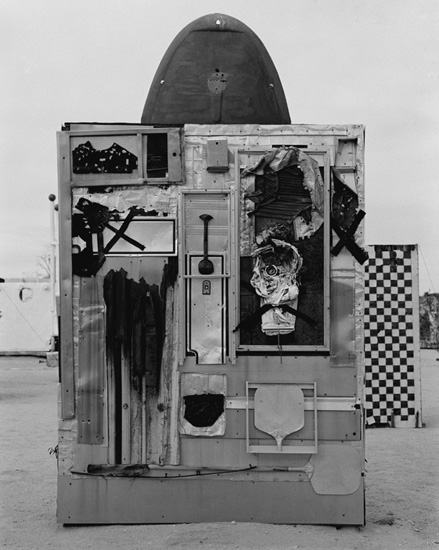

I saw the Purifoy sculptures outside Joshua Tree in the Mojave desert in California1 and responded to them because they made me ask questions.

The first point of research is really the asking of the question. My question was how could somebody make all these things in this inhospitable desert place? What were the circumstances of his life? I thought that you couldn’t look at this work without understanding something of the circumstances in which it was made.

What I saw in the desert was a vast field of big architectural sculptures made out of recycled and thrown-away materials, all relating both to the desert and to the city and a series of historical events I knew nothing about. They are shelters, shacks, meals, hanging places, graveyards, chains, ships—I could immediately think of one of the sculptures as something to do with lynching or as the ghosts of soldiers, but I couldn’t presume anything.

The works are kind of quite witty comments and also refer to contemporary art in a very knowledgeable way. What I wanted to do was to unpick what I was looking at and re-express it and thought I could do some photographs that would be an act of clarification in looking at these sculptures. So it was partly an exploration of what it meant for Purifoy to come from Alabama to the west coast and what the situation was in the years before and after the Watts rebellion in Los Angeles in 1965. It was also about what you could become if you were an artist and an activist and what then happened to you. In a way my work is incredibly ambitious because it’s trying to describe a whole period of time and another artist’s work.

Untitled, from: The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2014 silver gelatin print selenium toned

© Hannah Collins

Untitled, from: The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2014 silver gelatin print selenium toned

© Hannah Collins

I stayed at the site for a weekend and made photographs of the sculpture on a 5 × 4 camera. This, in itself, was research because I was staying in the desert where Purifoy lived and I understood a lot of things by being there, like what the time of day did in terms of space and sound and light and the kind of thoughts you might have if you were there over a period of time. The way you could see the sculptures changed massively over 24 hours so at night they sort of floated then, as day came, they sort of sank down. So one half of the work was purely visual and my own exploration and photographs.

Then there’s a soundtrack. As part of my research I found people who knew Noah Purifoy and interviewed them over a period of two weeks. I think I wouldn’t have been able to make the work without learning from them. They are African Americans who had all been politically active in the 1950s and 1960s and are now very old. They tell the story of some of the issues of the period of the Watts Rebellion in Los Angeles in 1965 and around civil rights at that time and afterwards. Each of them had a different perspective on it and told me very different things. From that the interviews became a choreographed version, a soundtrack that went with the photographs. From the first to the last interview was a massive progression just in terms of knowledge and that knowledge, in a way, is the work.

So, the aim of the work was to activate this site and to make you ask questions not only about Purifoy’s work but also about ideas of what is ethical and what are the issues about making art and being an artist. The questions I was asking are still there at the end and you are surrounded by my research into those questions.

I hope that you, as a viewer seeing the work, will be somewhere in a sort of no man’s land between the hearing and the seeing and so be forced to take on a very active and creative role which makes you almost like the artist.

The research consolidated my ideas and also shifted the work because I began with a feeling about something and, as I slowly gathered knowledge, my feeling changed a lot. It made me think a lot about my intentions, partly because I had to think about Purifoy’s intentions but also because it made visible the differences between my work about Purifoy and the work I was doing, and am still doing, in the Amazon.

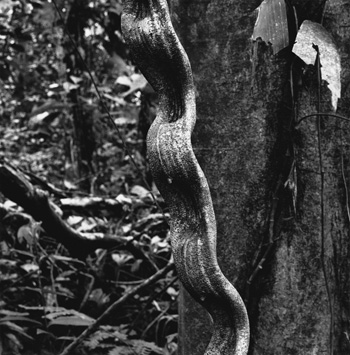

With the Amazon work I stayed with the Cofan tribe in Colombia and looked at the plants that they use to cure their bodies. This was just after having cancer. So, in one sense it was for my own personal reasons, which were, I think, to do with being surrounded by machines and thinking about other ways one might be cured or other ways the world might be in relation to one’s body. So I went to a place where there were no machines and no other options, you had to use nature.

But the research results were not very clear. This is because they were simply about what each plant was used for. It did show me the immense richness of the tribe’s understanding of their surroundings but it wasn’t very easy to feed it into work, whereas when the research is already within art, as it was with Purifoy, it sort of became more refined. Using something that is nature didn’t do the same thing at all, the core of it became more diverse and difficult to pin down the more knowledge I got.

Because Purifoy’s work was within art from the very beginning it strengthened the core of what I did. Whereas it’s been a more extended process to become clear about the Amazon project because it involved my going a long way from contemporary culture and the gap engulfed me at times. This made it a powerful task to reconnect the work I am doing on the Amazon with the present state of art or culture to find the contribution it might make.

One of the questions in showing the work is whether to show what the plants are used for. The shaman of the tribe I stayed with took me around and showed me plants that were used for different things. I took pictures of them, sort of directed by him, and we talked as we went about how the plants were used—for headaches, for skin problems, for prostate, for abortions and for other purposes. But do you gain anything knowing what these plants are used for? In reality, in terms of the work, I don’t think you do. The work is, in the end, a contemplation of lost knowledge. So there was a huge amount of research—with drawings, labels, names, origins and discussions—which is completely invisible in the final work.

Untitled, from: The Interior and the Exterior – Noah Purifoy, 2014 silver gelatin print selenium toned

© Hannah Collins

It’s an interesting opposite to the Purifoy work where the research work is visible and part of the final work. The extent of the research in the Amazon project is a hidden process—I always doubted it would strengthen the work for the audience to know what I knew. It exists only as a curatorial label, the curator writes about the process but you don’t see it in the final work at all. I ended up liking the gap between intention and result. It means that one’s access to the artistic process is limited to what is useful

In the case of the Purifoy work I had a huge amount of difficulty in starting because of my colour. I was a white person doing work about an African American and that in itself was problematic. I employed an African American researcher initially, which was the right thing to do politically, but I then realised that, by putting a researcher between me and the people who had known Purifoy, they missed my voice. In the end I just rang the huge list of people and talked to them and, because I knew exactly why I was doing the work, I could talk to them clearly about it. I think that it worked because I came from an entirely different background, had a lot of empathy for Purifoy’s work and was just trying to learn from them and not trying to impose anything on it. Also, simply by my being sincere because I really wanted to do the work.

In each situation I make sure there’s a representative from the people I’m working with who mediates my intentions and practice. When I worked on La Mina, with a gypsy community in Spain, one of the gypsy leaders worked closely with me and in the Amazon I was under the control of the shaman. I used that method for La Mina and it worked then and it’s always going to be my approach now. That work was about putting the gypsies in the foreground and, in a way, in order to do that, I had to take a background role. So, even though I was still there and aware, I was trying not to be present in order for the material itself to become more powerful.

I give practical and technical research a lot of attention. For instance, with the Purifoy work I started out with a sound guy who had mixed sound for me before. I could trust him but he thought we should carry out all the interviews in a completely controlled environment, which I knew wasn’t possible because, with people who are 80 or 90, I could not move them to a studio. I had to be able to get to the interviewees when they felt well enough to talk so I learned to use good sound equipment. I really worked at doing it well and then, when it came to mixing it, I worked incredibly hard to control the environment. At the point where it’s technical I try to be absolutely precise about it.

For instance, for the Purifoy pictures I took the biggest format camera I could and controlled every aspect as much as was possible. But I’m also often dealing with uncontrollable things. I mean, taking a camera to the Amazon, and trying to

take accurate pictures of plants, is the maddest thing to do because it’s a very alien environment and is aggressive, damp and hot; you can’t control it and no film camera is going to like that. It’s asking for trouble, really.

I sometimes slip up because I don’t have the right equipment but I accept the limitation. I quite like things not being perfect. While the intention and route need to be precise, often excluding many possible branches along the way, the carrying out of something is fluid and uncensored so the actual practice of making something has nothing to do with it being perfect. I work with film and you are taking a risk with film, always, because of temperature and putting it through machines. In the 1980s and 1990s you had control and now you don’t because less is manufactured, there are fewer choice of types of film, what you get might be older. I quite like it. If I run out of colour film I use black and white. But I think there are very good reasons for using film. The quality is better, or at least I find it more sensitive, and you can’t take as many pictures so you have to make more choices. It’s an act rather than being a reaction.

I think it’s a lot to do with how much time you give things because I know that if I haven’t done research the one thing that would absolutely panic me would be if I then don’t have time—which happens because nobody but you understands how long it takes to make images. People expect you to be quick.

I’m bad at keeping records, though I did it with the interviews I did in California and I’ve got much better at filing negatives. Although I do keep records they are a bit patchy because they reflect my interests at that time, not my interest in my own history. I’ve never had the idea of a career that is progressive and for which you therefore need to make a record of the progression. I think it’s a bit of a male idea of a career, actually. I have been driven by the momentum of the work itself and less by external opinion though, of course, I take it into account.

I pay attention to the challenges and questions of each piece while drawing on previous experience but the final work and the research become one at the finishing of a piece so I find I cannot evaluate either separately. I think I’m quite unwilling to evaluate a finished piece. I wish I did want to. It’s the bit that is difficult to judge and is, I suppose, judged by other people. Quite often, I think I don’t understand what I have done, even though I’d like to think I knew what I wanted and achieved it. But, in practice, if it’s worth something it has often gone beyond what you initially understood it to be because it’s gelled in a different way, and the pieces where you understood every element are the lesser pieces, because the process itself is alchemy in some way and can take you to unexpected places.

Sometimes, I’m horrified by things I’ve done. I always wish they were more which is very irritating because you should always think that, if you can get near your purpose in making the work, then that’s it, you’ve done it. Some pieces are much more successful than others. Some things don’t have a life when they’re made then have a life years later so the external, showing, life isn’t necessarily when you think it’s going to be. La Mina, my film about Spain and about Spanish gypsies, which I think is the best thing I’ve ever done, has barely been shown and never bought by anyone in Spain. When it is shown it gets a massive audience and that’s sort of ignored. It’s never had a decent piece of criticism in Spain. So I think it’s hard to work out where you stand in relationship to a piece of work sometimes.

The people who worked on La Mina are deeply loyal to the film; they write to me, they talk to me; they think about it and want it for different events. This is not particularly true of my other work so what does that say about it as a work? I think it says the film is talking about something a lot of people don’t particularly want to talk about or see. It doesn’t really speak about whether it’s got any value or not because it certainly had value for the people making it, and for me. I think La Mina will always be ignored because, for the Spanish, the gypsy population is the most peripheral population in Spain and is a difficult proposition. So to make a work entirely centred on that was madness really. I had huge ambitions for the work. I really wanted something that would allow this population to be visible in a good way. I was also an outsider, so I was perhaps equipped to make the work, because I wasn’t a Spaniard even though I’d lived there for 20 years. On the other hand, I realise now that I wasn’t entirely in tune with what the culture would allow me to do in Spain and it was just one step too far.

I chose to work with the gypsies because I identified with that population and was interested in its cultural place and the fact that it was so invisible. The task of making a whole culture that has a very limited visibility explicit, visible, poetic and central was a really interesting task. I think I failed, although the very existence of the film is a success but real success would have been if it had had a real audience and real discussion.

To what extent does research complement or enhance intuitive thinking? I start with intuition then order takes over then intuition comes in again at the end. So, for instance, I went to photograph Mandela’s birthplace and that was done on intuition. I was trying to find a place to work in Africa that would counterbalance a work I’d made about African migrants in Europe so I wanted to go to Africa, even though my experience was as a transitory visitor not that of a migrant. So I went to where Mandela was born, which has a site devoted to it, and that was done on instinct because I thought I would encounter something interesting. But, in reality, order had to take over because it turned out to be fairly difficult to do because of where it was—it was in the Transkei, in Mvezo, all sorts of reasons made it difficult to go there on my own and I couldn’t get any help there either.

Then once I had sorted these things out I could become intuitive again—so intuition is usually at the beginning and end I think. So, for instance, the work about the Amazon began with an intuition, order took over because I had to find the tribe and the place, to look after the equipment and the information gathered. Then at the end when I’d done all that I had space to work with what I’d done and make it into something in the editorial or curatorial stage. But there can be a sort of battle between research and intuition because the minute you have research and knowledge it sort of pushes your intuition aside. I’ve always had a battle between what I know and what I feel and they tell me different things, which can be difficult.

Interview by Shirley Read

Note

1 Noah Purifoy (1917–2004) was born in Alabama and spent most of his life in California. He was founding director of the Watts Towers Art Center. He was a sculptor who worked with found objects and saw art as a tool for social change. He lived in the Mojave Desert for the last years of his life where he created 10 acres of architectural sculptures, which is described as ‘one of California’s great art historical wonders’.