5 The most dangerous career traps

In their highly commendable book Why CEOs Fail, based on thousands of cases they analysed, David Dotlich, a former top manager at Honeywell, and Peter Cairo, a lecturer at Columbia University, listed the most common reasons for top managers failing in their careers. In their book they refer to the work of university professor Robert Hogan, who is internationally recognised as a pioneer in the area of personality typing of managers, as well as to the research conducted at the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL), which has been involved in research into good leadership since 1970.

Dotlich and Cairo were interested in the question of why around two-thirds of all managers in Western industrialised nations experience a critical career situation in the course of their careers, be it that they are fired, disempowered or receive a sideways promotion. They found out that many managers are not able to set up and develop an efficient team. Everything that inhibited them from building a team also hampered their performance as a manager, since a high-ranking manager can only exert a controlling influence over a company through her executive team. Many managers are unable to bring people together, get them to commit to common goals and set an example with their own behaviour (see Figure 5.0.1). They are, in a way, too focused on themselves, always wanting to stay in control. In their work with managers, Dotlich and Cairo identified 11 traits that could jeopardise careers, including arrogance, a tendency to over-dramatise or an inclination towards passive-aggressive behaviour. However, these career derailers, as Dotlich and Cairo call them, only typically become real career traps if they occur too frequently.

Figure 5.0.1 Skills lacked by unsuccessful managers.

Source: Dotlich and Cairo, Why CEOs Fail, 2003.

Executive derailers are traits that are deeply embedded in a person, forming part of their personality. These traits typically appear when a person is under a lot of pressure, i.e. when they can no longer use learned behaviour to conceal them. In such cases, these managers literally lose control of their own behaviour. These findings were also confirmed by a study conducted by the American leadership development consultant, Jack Zenger, and his colleague, Joseph Folkman, an American organisation psychologist. The study was published in the Harvard Business Review in 2009. Zenger and Folkman analysed the results of 360-degree feedback given on more than 11,000 managers and compared this feedback on the managers’ behaviour patterns to the managers’ actual career success, particularly of those who had been fired or downgraded. The first four most frequently criticised behaviour patterns were directly linked to the set-up and development of a functioning team (see Figure 5.0.2).

Figure 5.0.2 Traits that are most likely to make managers fail.

Source: Zenger and Folkman, Harvard Business Review, 2009.

In stressful situations, most people manifest negative traits. The personality psychologist Robert Hogan calls them risk factors. These are character traits that under normal circumstances might well be considered strengths. Yet if stress leads to these character traits being enhanced, then they can actually increase the risk of professional failure. If a manager is overworked, stressed, anxious or otherwise unsettled, these risk factors may appear and undermine their efficiency and the quality of their relations with customers, colleagues and employees. Employees and colleagues are generally familiar with their manager’s behavioural shortcomings. Some will tolerate these traits – usually out of fear of negative repercussions for them personally – or turn a blind eye due to a misconceived idea of loyalty. Others may perceive these negative traits, but frequently won’t give feedback for fear of jeopardising their own careers. This often increases the divide between self- and outside perception even further. It is not, therefore, surprising if managers themselves are hardly aware of their own behavioural weaknesses.

5.1 The blind spot

EXAMPLE

Indra Nooyi has been the CEO of PepsiCo since 2006. In the course of her career, the manager from Calcutta, India, has developed a reputation for being “pretty honest and outspoken”, as she told Wall Street Journal Europe. So, you sit in a meeting and someone presents a five-year plan, and a typical Nooyi comment in such a situation would be, “That’s crap. This is never going to happen!” Others who might have had the same thought would probably have expressed this in a much gentler way, as in: “That is very interesting. But perhaps you can try and think about this slightly differently.” Only when one of her colleagues found the courage to address her about this, did she become aware of the impact her behaviour had on others, namely that colleagues and employees feared her and were not, therefore, telling her the whole truth or giving her their full trust. This was undoubtedly an unpleasant remark to hear but it gave her the opportunity to reflect on her behaviour and to weigh up the pros and cons of her somewhat brash approach.

Research has, in fact, shown that managers develop certain risk factors in their behaviour early on in life, with their parents, peers, relatives and others. These behaviour patterns become so automated that they largely take place subconsciously.

Figure 5.1.1 The Johari window (derived from the first names Joseph and Harry).

Source: Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham, 1955.

Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham, two American social psychologists, coined the term blind spot as early as 1955 to describe this phenomenon (see Figure 5.1.1), where, for instance, the manager does not know or perceive his own behaviour, even though his entourage is very familiar with it. In our experience, such blind spots rank among the biggest risks in a manager’s career. Each of us has character strengths and weaknesses, but not to know them or fully understand the potentially damaging implications they might have, is simply disastrous. It leads to critical career situations hitting managers like a bolt out of the blue, while their entourage saw it coming from afar. The only way to expose a blind spot is to get feedback from outside, which fortunately more and more companies are doing regularly and in a structured manner.

In the book The Set-Up-to-Fail Syndrome, John Donaldson, former CEO of Thomas Cook, talks about how important it is for top managers like him to be given feedback, even if it sometimes hurts to get negative feedback. “When I look back at the way I behaved when I was directing one of the group’s two business units, I am encouraged by the progress I have made. […] If I was the CEO of the manager I was then, I think I’d have fired myself!”

5.2 Resistance to advice leads to failure

Blind spots occur alarmingly often among high-ranking managers. As previously mentioned, this is primarily because managers hardly ever get feedback and rarely think about or question themselves and their own behaviour. Many companies lack the necessary conditions for a culture of constructive criticism, which could, for instance, be established by introducing regular 360-degree feedback or employee surveys. Or, worse still, surveys are carried out but they do not lead to any consequences for staff members.

EXAMPLE

This is often due to a reluctance on the part of managers to have a mirror held up to them. These situations can be particularly frustrating for coaches, as was the case with one of our high-ranking clients from a listed company, whom I had been counselling for some time. He was responsible for around a dozen factories and the results were always good. In less than 15 years, he had worked himself up from the very bottom. In confidential interviews with various stakeholders he had nominated, I was able to get the picture of his manner of communication and management style. The feedback I received from these people was, in a word, catastrophic. One day, our client got a phone call from the company headquarters. The conversation with his boss was surprisingly short and was witnessed by a representative of the personnel department: he was fired, with immediate effect. The news caught him completely off-guard. He had actually been expecting to get a promotion. The reason given was that his aggressive management style was no longer tolerable. Employees and colleagues found him to be unchecked, offensive and hot-tempered. They had repeatedly complained about his angry outbursts and described his behaviour as downright tyrannical. The tragic thing about this was that my coachee’s career need not have taken such a turn at all, since he had long been aware of all his character flaws. Moreover, with regard to the results he produced, this man was one of the company’s shooting stars. His career had skyrocketed. Whatever he touched turned to gold. Yet this success had led him to disregard the warning signs: continuously surfacing criticism of his style. In other words, his willingness to learn something new about himself and others was very low. His division was in a good position, but his staff no longer produced their best results because he inspired them, but because they feared him. This turned out not to be very long-lived. When he left his division to take on a new job within the group, he fell back into his old way of doing things. Yet only very few at the headquarters really understood why this happened. The company had, for many years, even given him support to work on his management style. But my coachee was not able to change because he failed to understand the implications of his behaviour. And he is definitely not alone in this.

Figure 5.2.1 Four career-jeopardising factors.

Source: Survey by Karsten Drath Dec 2015–Jan 2016.

In the research I conducted for this book, I asked the participating managers about their own critical career situations. 10% admitted that their reluctance to accept advice had contributed to their career upheaval. 22% stated that they had not been assertive enough in their jobs. In 38% of the cases, blind spots were involved and in 65% of the cases the participating managers had not taken the existing political signs in their own surroundings seriously (see Figure 5.2.1).

This shows that focusing on your work is important, but tunnel vision is dangerous. It is vitally important for managers to keep their eyes and ears open, and to listen attentively when being given feedback on their work. Without the motivation to change, any coaching or other support received is questionable to meaningless. At some point in time, the corporate management will be forced to replace that manager because their misconduct is no longer acceptable, despite an otherwise outstanding performance.

EXAMPLE

The same was true for Steve Jobs who, in 1985 at the age of 30, was dismissed from the board of managers from the same company he himself had founded. His autocratic behaviour had lost him any goodwill and credibility he had had with his colleagues. The Apple staff both admired and feared him because of his visionary style coupled with narrow-mindedness, stubbornness and manipulative behaviour. Things went so far that these character traits earned him a name among his staff: Reality Distortion Field. In a speech he gave in 2005, Jobs described this time as follows: “It was awful-tasting medicine, but I guess the patient needed it.”

So, what are your strengths and weaknesses? What behaviour patterns characterise you? What is your reputation? The self-image that many executives have about themselves does not always fully agree with how others in their environment see them. Often quite the opposite is the case. A first step to increasing the accuracy of your self-knowledge is therefore to reconcile your self-image with the impressions others have of you. What might at first sound simple is not, in fact. First of all, it is important to get to know the image that other people have of us. In many companies, 360°-feedback is offered these days from a certain leadership position onwards. These are available both as internet questionnaires and in the “handmade” version, which is feedback collected through personal discussions with a coach. Our recommendation is to always use such possibilities. This is especially true if the results are treated confidentially, in other words they are only intended for the recipient. Otherwise, it might be assumed that the statements have been “politically” falsified. But even if no such feedback is offered, you can consult your environment directly. This requires not only some courage but also the ability to listen well. Here are some typical questions from our interviews that you can use for a feedback conversation:

What do you see currently as my biggest challenges?

What do you see as my biggest strengths?

What do you see as my biggest weaknesses?

How good am I at developing staff?

How well do I manage to form an effective team?

How do I behave under stress?

How cleverly do I deal with politics?

How well do I market myself and my team?

How good am I at overcoming silos in the company?

How would you describe my leadership style?

What recommendations do you have with regard to my future development?

So far so good. But there is one more difficulty. What happens when you receive such feedback? The greater the deviations between one’s internal and external images, the more the feedback hurts. Of course, this applies in particular when the external image turns out to be significantly more negative than one sees oneself. As already described in Section 5.1, The blind spot, strong criticism activates defence mechanisms in our personality that weaken the feedback, relativise or refuse it altogether. This is a normal mechanism in order to protect your own self-image. However, it is not always helpful.

Sometimes it takes a downturn in a person’s career before they are willing to accept feedback and to work on themselves. Based on what the managers stated in their programmes, the Global Leadership Center of the renowned French business school INSEAD has compiled the most common reasons for disregarding and refusing feedback. They are listed in Figure 5.2.2.

Figure 5.2.2 Ten reasons for refusing feedback.

Source: IGLC INSEAD.

What might at first appear amusing to read, is in fact not funny at all. A lack of openness to accepting feedback is one of the biggest risks for managers’ careers. You should listen carefully if you see yourself in one or more of these listed statements.

5.3 Executive derailers – what makes managers go off the rails

The reason for managers failing rarely has anything to do with a lack of intelligence, experience or ability. Instead, it is much more the result of illogical, unpredictable and irrational behaviour on the part of these highly qualified and experienced managers, who have the best of intentions. Dotlich and Cairo call these subconscious forces executive derailers, i.e. factors that can derail managers. In their work with managers, they have identified and named 11 of these derailers. Most managers are affected by one to three of these derailers.

It is rarely the case that all these derailers are highly developed in a manager. By contrast, there are only few profiles that show no concentration in any one area. It is, therefore, most probable that you have one or more of these personality traits. Perhaps you are brilliant at structuring and analysing problems and this ability has already spared the company a huge number of bad investments, or set your company apart from the competition. But when you are stressed, your tendency to analyse the causes of matters in detail means that you are unable to make decisions. This phenomenon is not uncommon and is known as analysis paralysis in the literature. As I mentioned before, the large majority of executives do not receive regular, structured and adequate feedback on their behaviour, and here I am not speaking about the annual performance talk, which in any case is seen by many as a farce or, at best, a necessary evil. This means that the blind spots remain and their damaging effect is allowed to unfold.

If managers receive useful feedback and can overcome their resistance to feedback, then many of them are able to use their sharpened awareness to manage their behaviour better and to get their executive derailers under control. This does, of course, presuppose a willingness to change.

So, what are the executive derailers? Dotlich and Cairo have identified the following factors which could jeopardise managers’ careers (see Table 5.3.1).

Table 5.3.1 Executive derailers

On the following pages I will elaborate further on the individual derailers and the typical behaviour patterns associated with these. You may be familiar with one or more of these derailers. At the end of the overview you can assess yourself.

Arrogance

This derailer is found in people who have a very high opinion of themselves with regard to their own competencies and importance. Executives with this trait are often unable to admit mistakes and learn from experience. They typically think along the lines of: I am right and everyone else is wrong (see Table 5.3.2).

Table 5.3.2 Arrogance

Caution

Managers with this personality trait have an exaggerated fear of making mistakes and being criticised for them. They find it difficult to make weighty decisions. Frequently, this results in a subconscious resistance to change, which in turn leads to good opportunities being missed (see Table 5.3.3).

Table 5.3.3 Caution

| Reflected or ideal behaviour | Unreflected or derailed behaviour |

| Before you make a decision, you go through the worst-case scenario in your mind to minimise risks. | You focus on the worst-case scenario and are often unable to make timely decisions. |

| You take your time with weighty decisions, as any wrong decision can have serious negative consequences. | You take your time with every decision, as every decision can have serious negative repercussions. |

| You reject projects if there are clear indications that the planning is erroneous. | You postpone decisions about projects because you have an unfounded suspicion that the planning might be erroneous. |

Habitual distrust

These managers lack social intuition, aplomb and trust. You focus on what is wrong, what runs or could run counter to your interests. You respond to potential conflicts with cynicism and extensive fear of the political damage this might do to you personally (see Table 5.3.4).

Table 5.3.4 Habitual distrust

| Reflected or ideal behaviour | Unreflected or derailed behaviour |

| Before making a decision, you carefully weigh up the pros and cons. | You try to avoid having the sole responsibility for decisions, as you primarily see the potential risk involved in every decision. |

| You are cautious in dealing with others, as you know that your actions are motivated by your own political or personal interests. | You assume that everyone’s actions are motivated by their political or personal interests. |

| You can take negative feedback and learn from it. You assume that your counterpart is trying to help you. | You find it difficult to accept negative feedback as you assume that your counterpart seeks to harm you with it. |

| When you give feedback, you try to provide a balance of positive and negative aspects of your counterpart’s behaviour. | You only give negative feedback. |

Mischievousness

These managers can be recognised by their charming demeanour, coupled with a great willingness to take unnecessary risks. Rules generally only apply to others. They always make exceptions for themselves. The kick managers get out of this means that they are sometimes not able to meet expectations and find it difficult to learn from experience (see Table 5.3.5).

Table 5.3.5 Mischievousness

Passive resistance

Managers with this trait tend to be indifferent towards other people’s expectations. This means that they are often seen as egotistical, stubborn and uncooperative. The fact that they don’t contradict what is being said, does not mean that they agree (see Table 5.3.6).

Table 5.3.6 Passive resistance

| Reflected or ideal behaviour | Unreflected or derailed behaviour |

| What you say and what you do differ when you feel you have no other option. | Generally, what you say and what you do are not the same. |

| Your environment is generally aware of the motives behind your actions. | Your environment is not aware of the motives behind your actions. |

| You generally try to avoid conflict, but share your point of view if the situation requires this. | You avoid conflict and very seldom express your opinion. |

| You are aware of the expectations of others and your obligations towards them. | You are not aware of and not interested in others’ expectations or your obligations towards them. |

Melodrama

People with this derailer display excessive enthusiasm towards other people or projects, followed by disappointment with those same people and projects as a result of a lack of emotional continuity. Your mood swings influence your decisions (see Table 5.3.7).

Table 5.3.7 Melodrama

Eagerness to please

Managers with this derailer tend to strive to be popular with everyone. You find it difficult to act independently and to take what may sometimes be unpopular decisions. Being liked is more important to you than anything else. This frequently results in you perhaps being superficially popular but there being no clearly recognisable direction in your actions (see Table 5.3.8).

Table 5.3.8 Eagerness to please

| Reflected or ideal behaviour | Unreflected or derailed behaviour |

| You are convinced that satisfied employees produce better work. | You are convinced that already one dissatisfied employee could jeopardise the performance of the entire company. |

| The teams you manage primarily reach decisions based on consensus following ample discussion. | The teams you control either hardly ever reach decisions or only make bad compromises. |

| You are able to quickly adapt to new situations and circumstances. | You are so flexible that nobody – including yourself – ever actually knows what your position is on any given topic. |

| You address conflicts and show a real interest in your counterpart. | You do not address conflicts, certainly not directly, and if at all, it is through third parties. |

Eccentricity

This derailer relates to the tendency to act in a very colourful, unusual and eccentric manner. Your need to be different from everyone else becomes an end in itself. This frequently leads to these managers being seen as creative, but lacking in practical judgement and tenacity when it comes to implementing their ideas (see Table 5.3.9).

Table 5.3.9 Eccentricity

| Reflected or ideal behaviour | Unreflected or derailed behaviour |

| You have a million brilliant ideas, many of which you put into practice. | You have a million brilliant ideas, which are never put into practice. |

| With your original and unconventional style you prevent routine and mediocrity. | With your unpredictable and irrational style, you intimidate and frighten your employees. |

| You have gotten many new initiatives off the ground, whose development you follow and control. | You have gotten many new initiatives off the ground, whose development you do not sufficiently follow and control. |

| You are able to adapt your unconventional leadership style if the situation requires it. | You refuse to adapt your unconventional leadership style or to stick to behavioural norms. |

Perfectionism

This behaviour is about being overly perfectionist, which costs a lot of time and energy and rarely leads to a sense of satisfaction. People with these traits tend to focus on the details and easily lose sight of the overall picture. This means that employees are frequently not able to develop their full potential and feel bossed around. This also leads to an overly long decision-making process (see Table 5.3.10).

Table 5.3.10 Perfectionism

Aloofness

Managers with this derailer are not interested in or even aware of other people’s feelings. They are emotionally detached and come across as intellectually superior. This frequently leads to them having great difficulty reaching their counterparts emotionally, never mind inspiring them (see Table 5.3.11).

Table 5.3.11 Aloofness

| Reflected or ideal behaviour | Unreflected or derailed behaviour |

| You create an impartial atmosphere, in which decisions are based on transparent and plausible reasons. | You create a cold atmosphere, in which all human and emotional qualities are avoided. |

| In the midst of crisis and conflict, you stay present and serene, which gives your employees stability. | In the midst of a crisis or conflict, you are no longer approachable, which unsettles your employees. |

| You are generally rather reserved, but if the situation requires it, you can build a relationship with somebody. | You come across as reserved and wooden, and you find it difficult to build a relationship with people in relevant situations. |

| You generally find nurturing relations and building alliances unpleasant, but if the situation requires this, you will personally take care of an important and influential stakeholder. | Irrespective of the situation, you are not able or willing to maintain relationships or to build alliances. |

Volatility

Managers with this derailer are always in the limelight. They love grand gestures and a dramatic appearance. They have an engaging personality and a strong need for recognition. They are constantly occupied with being noticed. This means that, under pressure, they are not able to focus on what is essential (see Table 5.3.12).

Table 5.3.12 Volatility

| Reflected or ideal behaviour | Unreflected or derailed behaviour |

| You use your charisma and charm to emotionally touch and inspire others. | You turn every situation into a stage and your counterpart into the audience that is there to admire you. |

| You use your ability to captivate and inspire people in order to draw the attention of the media, analysts or potential employees to your company. | You use your ability to captivate and inspire people to relish the attention and feel good about yourself. |

| You are able to make targeted and strategic use of your eloquence to achieve an important goal. | You are constantly colourful and extroverted, irrespective of whether the situation requires this or not. |

| You are able to scale down your presence, for instance in order to listen to others and to learn something new. | You are not able to scale down your presence and do not or only rarely reflect on what you actually wish to achieve with this. |

Self-assessment

Let’s be honest, were some of the behaviour patterns uncomfortably familiar to you? In Table 5.3.13 you can gauge the risk of whether and to what extent one or more of these traits applies to you. But beware with these self-assessments that you may also have a blind spot. In personality psychology, this is known as the social desirability bias. This is said to be the case if the answers someone gives make them appear more popular or socially acceptable than objective and truthful answers would have.

Table 5.3.13 Which traits apply to you?

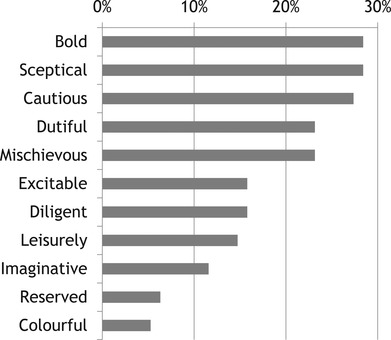

How honest were you in your self-assessment? And how well do you actually know yourself? The managers who participated in the research for this book were also asked about their executive derailers in the context of the critical career situations they had experienced. The results are presented in Figure 5.3.1.

Figure 5.3.1 Distribution of executive derailers amongst the study participants.

Source: Survey by Karsten Drath Dec 2015–Jan 2016.

According to this, it would appear that excessive arrogance and too much self-confidence as well as the rough opposite, namely too much distrust coupled with too much procrastination and weighing things up, are the worst traits in the study participants’ self-assessment. This is followed by the tendency to be too perfectionist and having too great an appetite for taking risks. What were least commonly found in the self-assessments were the tendency to need a big stage and an audience and to be in the limelight, as well as its opposite, emotional withdrawal and aloofness.

The type of study presented here is, of course, subject to the phenomenon of social desirability and, therefore, has methodological weaknesses. Correctly done, the derailers of all study participants should have been recorded in a complex personality questionnaire, such as the Hogan Development Survey. However, this would have been too complicated and time-consuming. As we mentioned at the beginning, the majority of those participating in the survey for this book came from Germany, the UK and the USA. According to the Hogan database, which comprises several million records, the following derailers are the most commonly found in these countries (see Table 5.3.14).

Table 5.3.14 Most commonly found career derailers in Germany, the UK and the USA

| Germany | Habitual distrust Aloofness Mischievousness |

| UK | Aloofness Passive resistance Eagerness to please |

| USA | Aloofness Perfectionism Eagerness to please |

What stands out, by comparison, is that the derailer aloofness is to be found amongst the top three in all three countries, while in the results of the study on critical career situations it ended up second to last.

How can that be? This is a good example of the social desirability phenomenon. At the beginning of this chapter I showed that, from a statistical point of view, managers are most likely to fail in their careers in building a functioning team. Empathy and interpersonal skills are needed to build such a team. Indeed, these traits were described by the study participants as the most important prerequisites for long-term professional success. However, in actual fact, many managers do not have this ability, or still have to work on developing it. But that is something nobody likes to hear, of course. This is why there are deviations in the statistics. Self-reflection and assessment are good and important, but they do not spare you from having blind spots. The only thing that can remedy this is to receive external feedback that is as objective as possible, coupled with the will to listen and to work on oneself.

5.4 Are managers prisoners of their own personalities?

Many managers are not able to change their own behavioural weaknesses by themselves. In any case, many do not believe that this is still possible when you are in your late forties or early fifties. After all, “everything somehow still works quite well”, as the CIO of a DAX-listed company once told me. “I am much too experienced to change much now.” It might not be a surprise that he is no longer with that company. Experience is, of course, not delimiting of behaviour change, as modern brain research has meanwhile sufficiently proven. The key word is neuroplasticity. This term describes the brain’s ability to integrate new knowledge and new skills acquired over the course of a lifetime into a complex network of experience. Moritz Helmstaedter from the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology in Martinsried, Germany, is researching this area. In tests he has proved that the brain is still as powerful in learning at the age of 60, as the brain at the age of 10 years (see Figure 5.4.1). This means no less than that individual patterns for our thinking, feeling and acting at any time and into old age are changeable through repeated processing of other patterns.

Figure 5.4.1 The principle of neuroplasticity.

Source: Christian Elger, Keynote ICF-Conference “Neuro-Leadership”, 2013.

As an absolutely mandatory prerequisite, this does, of course, demand that the manager concerned really wants this. This is easier if you consult an experienced coach or are fortunate enough to have a good mentor. You should at least have a confidant in your personal environment whom you can ask. This might be a team colleague, a superior or a trusted employee. You could ask them how they perceive you ‒ in terms of your leadership style, communication, team management and personal development.

If you receive credible criticism, it is important to systematically work on it. This takes time and patience. You can only improve your behaviour step by step. Important questions to be asked in this context are:

How am I mentally wired?

What are my preferences?

What do I want exactly?

How am I an obstacle to myself in this respect?

What are my inner motivations and convictions that trigger certain behaviour patterns?

How can I get a better grip on this unwanted behaviour?

This kind of work has nothing to do with giving up your personality, as many of our clients fear. It is much more about raising your own potential and integrating more of this into your daily actions. It is more about being yourself, just with more elegance and aplomb. When you spend as much time as I do studying the biographies of successful managers, then it becomes apparent that nearly all of them have had to work hard on themselves in order to get a grip on their limiting and potentially career-damaging traits. The bad news is that this requires a lot of hard work and self-reflection.

But there is also good news: we are not the prisoners of our own personalities and the behaviour preferences associated with them. We have a choice. This characteristic is what distinguishes us from animals. We can choose a form of behaviour that runs counter to the preferences that make up our personality, because the situation requires it or because it will make us more successful. This is what I mean by elegance and aplomb. Everyone can work on themselves. Successful leadership personalities perhaps just do this with more commitment and discipline.

EXAMPLE

Let us take Richard Branson as an example. In order to promote his airline Virgin, he even dressed up as a bearded stewardess with a bright red uniform and matching lipstick. To the Independent newspaper he commented: “Every time I am asked to make a fool of myself like this, I feel queasy.” In actual fact only a small part of this paradise bird act is part of his personality, but he has learned to play this role because it works excellently. Before Branson became the boss of the airline, he was shy and tended to remain in the background. He had to work hard on himself to adopt this flamboyant role and to feel comfortable with it. This was the only way he could expand his behavioural repertoire and use his popularity to benefit his company.

This example demonstrates how it is possible to enhance your toolkit with additional tools. Working on your own behaviour patterns can also open up other possibilities, as the following example shows.

EXAMPLE

When Cisco’s top management decided to improve collaboration through more open communication and empowerment, it was CEO Jahn Chambers who found it extremely difficult. He has always been used to dominating management meetings, and has found it hard to hold back and not express his views on all counts. In 2014, he commented to the Harvard Business Review: “In the beginning it was difficult for me to be open to more collaboration. But as I learned to let go of control and give the team more time to come up with the right conclusions, I found the decisions to be just as good or even better than before. But first of all, I had to be patient enough to let the team think for itself.”

The American personality experts Zenger and Folkman confirmed these findings. In a study published in the Harvard Business Review in 2013, they analysed the results of 360-degree feedback of nearly 550 top managers from 3 different types of organisation: a bank, a telecommunications company and a university. The competencies examined were based on the key skills that have already been described at the beginning of this chapter. Nearly 100 of these managers scored really badly in 1 of the 16 areas of competence. In other words, they performed worse than 90% of the other study participants. Subsequently, the managers were given the opportunity to be supported by a professional coach. After some time had passed, 360-degree feedback was once again used to examine whether and to what extent the evaluations of the protagonists had changed. The result was surprisingly clear. Over 70 of the 100 managers had significantly improved. The evaluations revealed an improvement not just of a few per cent, but of on average 30% compared to the initial assessment. With external support and targeted work, around 70% of the study participants were thus able to turn clear shortcomings into slightly above-average results.

Even well-entrenched behaviour patterns can be changed, simply by consciously acting differently. However, this can only happen if there is the will to change. It is also true that behaviour patterns that run counter to our own personality require us to invest more energy than reaction patterns we have practised since childhood. Self-reflection, impulse control and self-management do not just happen by themselves, but require the continuous investment of cognitive and emotional energy. Every very introverted person who has just given a speech in public will feel exhausted afterwards, when the excitement has subsided. Anyone who is scared of flying and has just overcome their panic to face a flight will be tired after their adrenaline levels have returned to normal.

This energy must be regularly recharged, otherwise it will be like a Formula 1 racing car that is permanently losing fuel. This, of course, requires the basic ability to be in tune with oneself and perceive one’s own energy level.

Bibliography

Barsoux, Jean-Louis; How to Become a Better Leader; MIT Sloan Management Review, Cambridge, USA, March 2012.

Dotlich, David L.; Cairo, Peter C.; Why CEOs Fail; Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, USA, 2003.

Drath, Karsten; Resilient Leadership: Beyond Myths and Misunderstandings; Taylor & Francis, Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2016.

Hogan, Robert B.; Management Derailment; APA, Washington DC, USA, 2009.

Zenger, Jach; Folkman, Joseph; Ten Fatal Flaws That Derail Leaders; Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, USA, 2009.