6

HR Practices That Add Value

Flow of Information and Work

PEOPLE AND PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT—the topics covered in chapter 5—are the traditional province of HR, but HR professionals need to devote their attention to two additional areas as well: the flow of information and the flow of work. These emerging HR activity areas have great impact on the human side of the business and add value to key stakeholders.

- Flow of information. Organizations must manage the inward flow of customer, shareholder, economic and regulatory, technological, and demographic information to make sure that employees recognize and adapt to external realities. They must also manage the internal flow of information across horizontal and vertical boundaries. HR professionals, with their sensitivity to people and processes, are ideally suited to assist with both information flows.

- Flow of work. Organizations must manage the flow of work from product or service demand through order fulfillment, to make sure their obligations are met. To do so, they distribute work to individuals and groups, and set up a structure to integrate the varied outputs into a cooperative whole. They design work processes and set up a physical environment that promotes effective and efficient work. HR professionals are ideally suited to assist in all aspects of the flow of work.

Like chapter 5, this chapter sketches the underlying theory for each topic, then outlines the menu of choices open to HR. This chapter also discusses action planning, offering templates to help you implement the choices you make and to track your progress in implementing the chosen practices.

Flow of Information

Information is the stuff of which organizations are made, by which they function and through which they prosper or fail.1 Information permits a company to identify and meet the demands of competitive markets, creates company value in the eyes of customers and shareholders, and enables a company to function within the ethical parameters of its communities. Through information, organizations share goals, craft strategies, make decisions, and integrate behaviors. Information enables innovation to proceed, change to occur, service and quality to improve, costs to stay under control, and productivity to increase. It determines who has influence over which issues and who does not, giving meaning and direction to work and purpose to the lives of managers and employees alike.

Theory of the Flow of Information

The flow of information drives the flow of value. Investors, customers, line managers, and employees all value the organization based on what they know about it, either from observation and personal experience or from reading and listening. And since firsthand information is frequently limited to relatively small subsets of stakeholders, it behooves the organization to make sure the word spreads.

This principle of information flow applies at all levels. Companies need to be meticulous both in financial record keeping and in preparing clear and accurate reports for investors and regulatory agencies. They need both to establish the basics of intangible value discussed in chapter 3 and to make sure capital markets learn about their intangible assets. They need both to treat customers and employees well and to make sure that current and prospective customers and employees confidently expect such treatment.

Information is also what binds supply chains and work flows together. The more an organization can do to make sure information passes smoothly to the places where people can use it, the better off it will be.2 And since information is much of what creates culture, organizations that create and sustain effective cultures manage information effectively. Thereby, employees clearly understand the importance of their work to customers and to the organization as a whole.

Choices Around Flow of Information

Information choices fall into two broad categories: communication strategy and information transmission. Underlying both categories, however, is the mindset within the organization. It needs to be focused and receptive, or communication will fail. Building an organization with a focused and receptive shared mindset is a formidable challenge, but it can be done when senior management leads the way, modeling and legitimizing diverse and reality-based ways of thinking rather than clinging to an institutionalized dominant paradigm.

Communication Strategy

A comprehensive communication strategy creates value through messages designed to meet the needs of each stakeholder. All messages need to be based on a clear understanding of their immediate purpose and to reflect the company’s overall leadership philosophy. For example, if the leadership style is “telling and selling,” then messages will be directive. Employees will receive brisk statements of what they are expected to do. If the leadership style is “involving and empowering,” then employees will receive messages designed to evoke personal action by sharing basic information about customers, competitors, company financial performance, and other strengths and weaknesses. Here are some other basic choices.

- Ensure consistency between messages and reality. Organizations need a seamless message that links internal and external stakeholders. With today’s multiplicity of information channels, it’s impossible to present one face to employees and another to the world. Brand identity, customer experience, and organizational capability must all be consistent.3

- Codify commonly understood concepts, language, and logic.4 A key strategic element is the establishment of powerful and flexible concepts (“We focus on customers”), language (“When we talk about customers, we mean external customers”), and logic patterns (“Customers determine our products, not vice versa”). It takes time and discipline on the part of management to establish these foundational elements—but without them, communication remains problematic.

- Choose an “integrity shepherd.” Designate a member of the management team to keep track of the company’s concepts, language, and logic. Part of this shepherd’s job is to help senior leaders give messages time to develop and take root, resisting the temptation to change too soon.

- Select media consistent with the message and audience. This choice may seem obvious, but people often get it wrong. They send out important and emotionally loaded messages through e-mail or memos; they hold expensive off-site meetings to plan cost reductions; they phone critical suppliers or customers instead of talking face-to-face.

- Know and speak to your audience. Communications must be designed to reach people in their frame of reference. If your concepts, language, or logic seems too alien, your message is unlikely to be grasped or accepted.

- Ensure integration and alignment. Virtually all HR practices have an important communication component; they reveal what the company really is and does. Likewise, top management needs one voice when it comes to policy and direction, and corporate communications. Corporate messages, leadership communications, and HR signals must be in sync with one another. It’s a major problem if the leadership says the organization will go in one direction, while HR hires, trains, promotes, measures, and rewards people for going somewhere else.

- Establish accountability. Communication is everybody’s responsibility. From the CEO to the janitor, everyone needs to be mindful of and effective at communication; otherwise, chaos reigns. At the same time, someone must develop a comprehensive strategy for everyone to follow. In small firms, this is generally the CEO, but larger firms tend to select a communications specialist to work closely with the top team. Increasingly, this specialist reports to the senior HR executive, which helps keep the organization’s communications efforts and HR practices consistent.

- Measure and improve communication effectiveness. A comprehensive communication strategy establishes mechanisms for detecting and correcting errors.5 Management by walking around is the most straightforward way to learn how well messages are being received, but in complex environments, formal and informal feedback meetings and statistical surveys can evoke more detailed responses. With such feedback, the organization can make sense of its communications processes and manage communications more effectively.6

Information Transmission

Information moves in five directions: from outside an organization to inside, from inside to outside, from the top down, from the bottom up, and across individuals, teams, departments, and business units. For each direction, the issues are similar (Who sends? Who receives? What is sent? How is it sent? When is it sent?), but the choices differ. There are so many permutations of these issues that the range of choices can seem overwhelming. The following sections outline the choices we have found to be most valuable to customers, investors, managers, and employees. Because our recent research suggests the central importance of HR in moving external information into the firm, we begin with that flow.7

OUTSIDE IN

- Know the “what” and the “how much” of customer information. Organizations need to know what their customers want. Many companies gather information from focus groups or interviews of existing customers. This is useful for what current customers want but doesn’t indicate to what degree the total market has the same wants. Answering the “how much” questions requires market research on a large enough scale for statistical validity.

- Know most about the most important customers. As discussed in chapter 3, for most businesses, some customers matter far more than others—they buy more, they provide greater returns, or they are less costly. As a result, it is useful to segment the market into meaningful categories before devoting much time to research.8 Most companies know much about current customers that have both large potential and small potential. They devote much of their attention to hanging on to current buyers both large and small. They often become complacent and ignore the greatest opportunity for growth—potentially large customers with whom your company currently does little business. Obtaining accurate information from this category is more difficult yet conceivably more important for sustained business success.

- Gather comparative data. Comparisons bring data to life. How do your customers compare you against your competitors? How do your customers compare you today to how you were doing a year ago? How do your customers compare you to their own expectations?

- Create and gather information through joint interaction with customers.9 One powerful way to grasp the concepts, language, logic, and priorities of customers is to join them in mutually beneficial activities. Such activities might include joint R&D efforts, joint solving of production or distribution problems, joint training programs, and joint interaction with customers’ customers. 10

- Expose management and employees to customer requirements. Direct customer interaction can often change in powerful ways how managers and employees think and behave. 11 Invite customers to management meetings, disseminate videotapes of customers describing how their lives have been influenced by your products and services, involve production employees in market research, bring customers in to plant operations and company celebrations, or have employees visit customers’ businesses or homes to see exactly how products add value.

- Bring investor logic into the firm. Key investors have much to contribute in management and employee meetings. Investors tend to be objective, blunt, and highly credible when they provide feedback on company performance.

- Enlist vendors as additional sources of innovation. Outsourcing innovation mitigates risks, accelerates innovation, and reaches otherwise inaccessible talent.12 Some companies are going beyond calling for proposals from specific vendors. Eli Lilly’s InnoCentive.com Web site, for example, lists difficult pharmaceutical and technical challenges—and awards from $5,000 to $100,000 to the scientists (and hobbyists) around the world who propose successful solutions.

INSIDE OUT

- Create the substance of the brand, then communicate it. The perception of quality products and services is essential, but it must be supported by products and services that, in fact, have high quality. In the appliance industry, for example, Maytag has worked to communicate its quality by emphasizing the loneliness of the Maytag repairman. First create the reality; then create the perception of reality. Ultimately, companies win on the basis of customers’ positive perceptions that are backed up by positive realities. For example, Maytag wins on perceived quality that is supported by high-quality products.

- Communicate the brand image and then work to sustain it. The perception-reality tie works both ways. Brands can be powerful statements of aspirations. For example, one of the world’s most famous corporate slogans is GE’s “We bring good things to life”—the ongoing goal that GE continually pursues through its customer-focused products and services. To embody their brands, companies must hire the right people, give them the right training, provide the right measurement and rewards, communicate the right internal messages, and develop the right kinds of leaders.13

- Create emotional ties with customers. When customers move beyond valuing a brand’s utility to loving it, the company gains tremendous traction in the marketplace. Consider Harley-Davidson, for example: its customers tattoo the Harley-Davidson logo on their arms! Harley works to embody its culture proposition of fun, counterculture, and outdoor camaraderie. It responds to customer feedback in product design and communicates that responsiveness through super-engagement events such as HOG (for Harley Owner’s Group) rallies, where its executives mingle with customers.

- Create ties of trust with customers. The intangible value of trust is especially important to communicate, and that requires both behaving in trustworthy ways and being known for it. The Johnson & Johnson Credo is perhaps the best-known example of how a company creates ties of trust with customers. J&J’s handling of the infamous Tylenol tampering incident demonstrated its willingness to place customers’ best interests first. The company has built a remarkable level of consumer trust in its brand.

TOP DOWN

- Present major issues in top management’s voice. The source enhances the impact of a message, or detracts from it. In one study, 62 percent of employees reported preferring to hear about major issues from top management—and only 15 percent of senior managers said they were doing so.14 But talk alone backfires—messages must be communicated through actions as well as words. HR’s role is to encourage top management to act consistent with their talk.

- Present action items in the immediate supervisor’s voice. The most credible source for information aimed at frontline change is the first-line supervisor.15 HR needs to make sure that supervisors are trained in communication skills, and that they have access to the messages that need to be shared and the information that is relevant for their respective departments or teams.

- Balance the “whats” and the “whys.” Many managers and supervisors have a natural tendency to communicate what is happening, what is needed, and what is expected. They may be impatient when it comes to taking the extra time and effort to communicate the underlying reasons. Yet when people understand the “why,” they are more likely to accept the “what” and do the “how.”

- Balance the big picture and details. Employees need to understand how their individual jobs add value for the whole company. They need to understand capital market demands, competitive threats, and customer expectations.16 At the same time, they need information about their own responsibilities and performance, the consequences of good or bad performance, as well as technical information and how to get problems solved.

- Balance good news and bad news. Some executives are effective at sharing bad news but do a poor job sharing good news. Others are excellent at sharing good news but hesitate to share bad news. Generally, what employees value most is honesty. Claims that the news is all good tend to create distrust—and may encourage complacency anyway. Unmitigated bad news can wreak havoc on morale; employees need to know what they have to work with as they begin urgent improvements. And if the outlook is uncertain, then that should be part of the message. People unfailingly sense unstated uncertainty, and the rumor mill takes over—almost always painting the worst possible scenario.

- Apply multiple media. Employees generally prefer face-to-face communication—“town hall” meetings, team briefings, two-way video broadcasts, management by walking around, corporate celebrations.17 However, in increasingly cost-conscious and globally dispersed business environments, face-to-face communications are being augmented by videotapes, one-way video broadcasts, teleconferences, direct mail, intranets, company newsletters, and even local newspapers and radio.

BOTTOM UP

- Acknowledge the importance of upward information flow. Upward channels tend to be the most constricted in the internal communication system.18 Given the perceived power differences, bottom-up information flow does not occur naturally. Employees frequently recognize problems but fear that senior managers will reject honest feedback with embarrassment or anger. The burden is on management to make it clear that even negative information is welcome.

- Be where the action is. As Jack Welch was fond of pointing out, “Those closest to the work know better what to do than those further away from the work.” This understanding of and respect for people at the bottom of the organization is what led Larry Bossidy to visit with more than five thousand employees during his first two months as CEO of AlliedSignal.19

- Collect and use empirical data. It is easy to overreact to a few loud voices from the bottom when they’re the only voices management hears. If an organization establishes a database of employee views on ongoing issues, management will be able to make judgments more rationally. Dell, for example, has established a database it calls the “Dell pulse” to collect regular feedback on key issues from a large number of employees.

- Provide avenues for upward information flow. In addition to welcoming upward communications, management must create channels to facilitate flow. Leaders can attend town hall meetings, sponsor employee breakfasts, eat in the employee dining room, visit employees in their workplaces, and involve themselves in employee suggestion programs. And they can make themselves available and respond to lower-level employees.

SIDE TO SIDE

- Remove obstacles to effective lateral communications. Organizations need to get peers talking together. The problem is, sometimes the receivers don’t want to receive (the “not-invented-here syndrome”). And the givers don’t want to give (“When promotions occur, I want to look better than you”). GE has greatly leveraged lateral communications by understanding such obstacles, removing them, and putting incentives in place to encourage greater volume of side-to-side communications.20

- Promote efficiency. The more communications flow horizontally, the less information must flow up and down through hierarchical layers. Because the overall social and financial cost of communications is reduced, more information gets through, resulting in better coordination as well as a simpler and less costly organization structure. This dynamic has allowed Dana Corporation to move from twelve or thirteen layers of management to five or six.

- Develop a system of integrated horizontal linkages. Horizontal communications flow can best be viewed as a series of systems: interpersonal information sharing and also interteam, interdepartmental, interdivisional, and intersector sharing. An effective framework will account for and integrate all these levels. Such a framework strongly contributes to an effective learning organization.

- Expand market opportunities. In a diversified business, product integration can begin anywhere to create wealth all along the value chain. But it doesn’t just happen. Disney, for example, outperforms most of its sector because of its mastery of information flow and cooperative ventures. By simultaneously leveraging themes from movies, video games, fast-food promotions, and theme parks, Disney characters keep earning.

- Employ the full range of vehicles for horizontal information flow. Information can follow an array of channels: working meetings, staff transfers, ad hoc committees and task forces, temporary work assignments, best-practice discussion sessions, and online exchanges. At Hewlett-Packard, Dave Packard found that one of his single greatest leadership challenges was to get people and businesses in one part of HP to willingly share information with their counterparts elsewhere in the company.21 To meet this leadership challenge, he allocated top management time to ensure the utilization of the full range of horizontal communication vehicles.

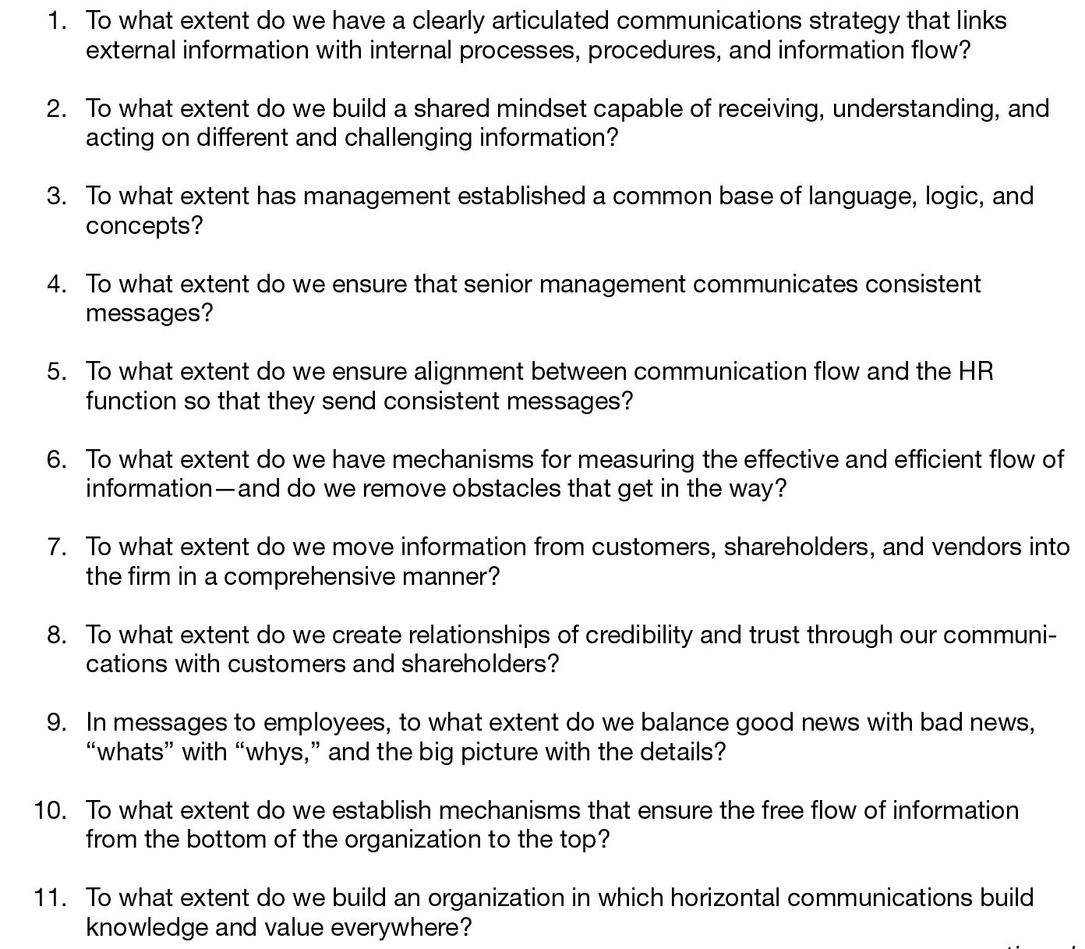

Action Plan for Flow of Information

Communications flow can be approached on many levels, but it’s apt to be counterproductive to try too much at once. Instead, select between two and four HR practices to focus on first. The communications audit shown in assessment 6-1 will guide your attention to the types of practices likely to have the biggest payoff.

ASSESSMENT 6 - 1

Audit for information flow

Once you’ve assessed the most productive categories, you can ask which of all the ideas you’ve listed will do most to build stakeholder value. You can then build an action plan by following the template in exhibit 5-1 in chapter 5.

Flow of Work

Work is what ultimately transforms ideas and raw materials into products and services. It is the mechanism by which organizations fulfill their purpose in society. Too often, HR professionals have not participated in work flow decisions. We believe that since work flow decisions at all levels organize people to deliver value, HR professionals should play an active role in this area. Three key questions warrant attention: Who does the work? How is the work done? Where is the work done?

Theory of the Flow of Work

Work flow adds value to all stakeholders. Investors can have confidence in a consistent flow of products and services at the right volume, cost, quality, and speed. The velocity with which products and services flow within the organization through appropriately structured and organized work directly influences the velocity of cash flow and level of margins. Customer experience emerges from the ways the company organizes work processes, ensures accountability for customer decisions, and establishes physical arrangements. Managers coordinate how work is carried out to ensure that critical capabilities (e.g., speed, collaboration, learning, efficiency) are embedded in the organization’s culture. Through the flow of work, employees know their roles and what is expected of them. They are able to focus on high- rather than low-value-added work, and they know who is accountable for results.

Work Flow: The “Who” Choices

Structure must fit the firm’s strategy. Structural decisions should be contingent on the intent to support and drive the business strategy. Making choices relative to who does the work requires four sets of decisions about the structure of the organization: overall corporate portfolio, differentiation, integration, and configuration.

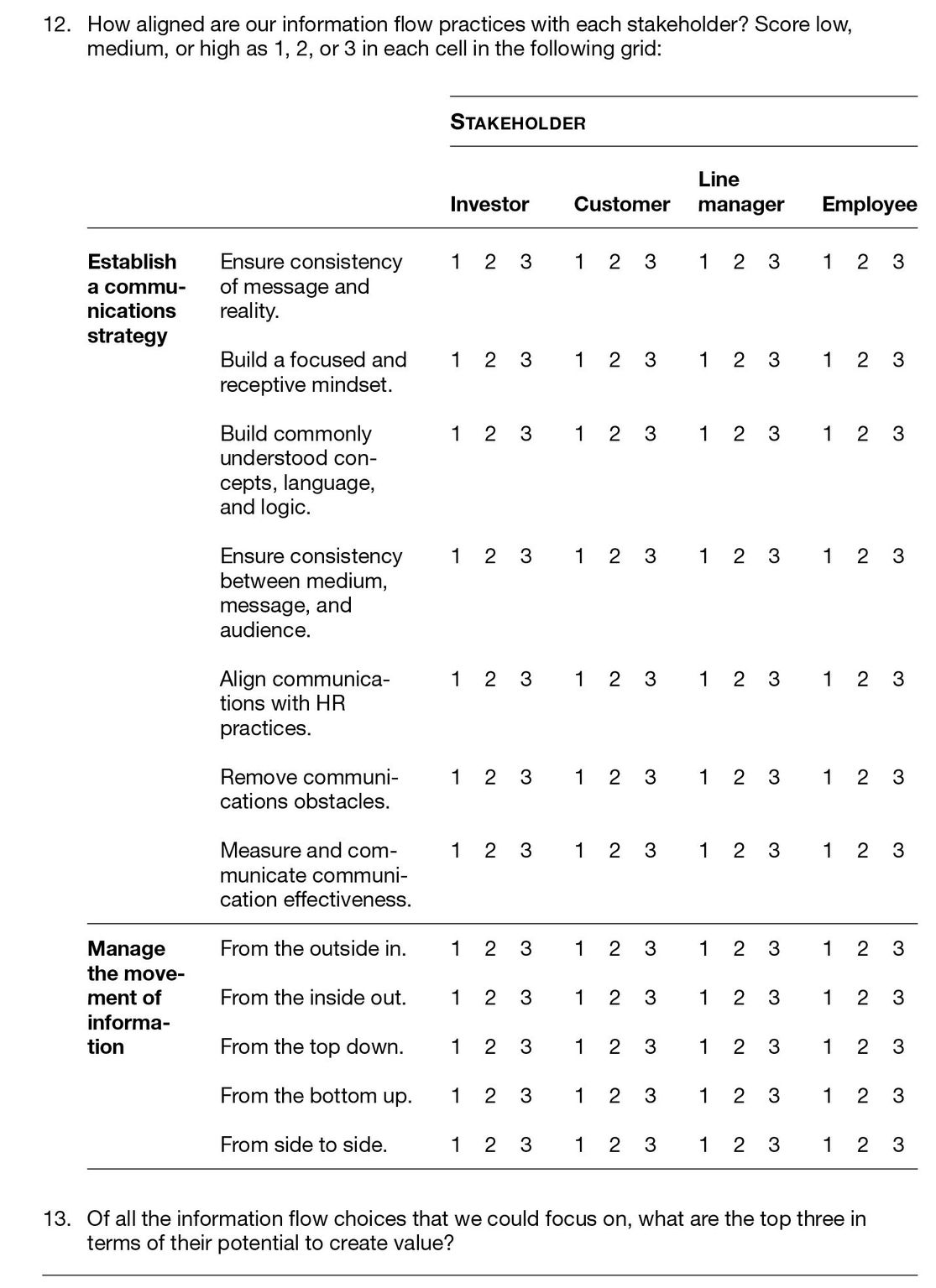

Corporate Portfolio

The fundamental decisions for any company involve what businesses to be in and what relationship its business units will have to one another. The resulting strategy can be refined with decisions about industry, customers, competitors, technology, products, and culture. These six strategy choices set the pattern for one of four portfolio structures—a single business, related diversification, unrelated diversification, or a holding company—as outlined in assessment 6-2. The worst of all worlds is to muddle along without clear choices about relationships among the composite businesses. Note that if you answer 1 or 2 to the six strategy questions in assessment 6-2, you should probably have a single business unit or related diversification structure. If you rated 4 on the six dimensions, you should have a holding company. In-between scores would indicate related or unrelated diversification.

The idea is to align strategy choices with structural responses—that is, to avoid moving toward a portfolio-based diversification strategy while clinging to a structure based on integration, or the reverse. HR professionals can frame and encourage conversations that promote alignment and raise concerns when misalignment occurs. Here are the essentials of each choice.

Single Business Unit

Frequently (but not always), companies sell a single product or service or a set of similar offerings from one business unit at one location. Marketing Displays International, for example, produces sign frames, light boxes, and picture screens for use in airports, gas stations, and retail outlets, and as fast-food menu boards. It employs 160 people in its single combined office and production facility, and it has one department each for accounting, HR, legal, engineering, and production. These departments are well integrated with each other through meetings, lateral communications, strategic planning, and physical proximity of their offices. But this single–business unit approach isn’t limited to small companies. Herman Miller, with around six thousand employees worldwide in the office furniture business, also has a strong central office with centrally coordinated staff functions.

Related Diversification

A company may consist of a set of relatively similar businesses with common products, services, customers, culture, or competitive criteria, and with explicit and extensive mechanisms to take advantage of these commonalities. Wal-Mart Stores and Sam’s Club, for example, form a company whose similarities outweigh its differences. Its management works intensely to share and leverage insights about logistics, consumer trends, real estate purchases, labor requirements, competitors, pricing, and inventory management.

ASSESSMENT 6 - 2

Strategy choices and structural responses

Unrelated Diversification

Under unrelated diversification, differences across business units—in products, services, customers, competitors, and requirements—outweigh similarities. Shared learning, management, values, and brand may promote overall corporate success. However, such companies must resist the temptation to treat the disparate businesses alike, because a one-size-fits-all approach can impair business unit wealth creation. Cardinal Health, for example, derives its primary revenues from its wholesale pharmaceutical distribution business. It also manufactures and sells surgical equipment and pharmaceutical technologies and services, and it provides health care automation and information services. Despite some common threads, the differences in product and service offerings, customer demands, and competitive constraints result in substantial cross-business differences. Cardinal Health prospers by allowing its businesses to function as independent units with a modest level of coordination and synergy.

Holding Company

A holding company manages businesses that have almost nothing to do with one another. It is likely to have central finance, accounting, and legal functions for oversight, but most support activities are embedded within the business units. The Tata Group (one of India’s largest private employer), for example, includes engineering, materials (predominantly steel), energy, chemicals, communications, retailing, information systems, and consumer products and services. For most of its history, these businesses have functioned almost autonomously under a strict set of ethical and legal values, but initial efforts are now under way to examine options for sharing relevant insights from different businesses for the benefit of all.

Differentiation

Companies can organize themselves primarily around products, markets, technology, function, or geography, or a formal combination called a matrix. Most use various combinations to one degree or another. For example, a company that relies on sensitivity to local markets generally organizes itself around geography. Within local regions or countries, it then organizes around function, product, or technology.

- Product structure. Organizing by product offerings works best when competitive advantage requires fast development and when product life cycles are short. Intel is one of the world’s best examples of a product-driven company.

- Market structure. The increasing purchasing power of buyers and the shift toward service-based economies can drive a company to organize around markets.22 Many professional service firms take this approach as they organize by industry segments.

- Technology structure. Companies organize around technology to allow new technology-based business propositions to take shape. This structure removes innovators from the mainstream of the company and protects them from other business units that may feel economically, politically, or culturally threatened. The Apple Computer Strategic Investment Group, the Lucent Technologies New Ventures Group, and Philips External Corporate Venturing exemplify this approach.

- Functional structure. Most small firms organize around functions such as finance, manufacturing, and marketing. However, this pattern works best in large firms where most tasks are simple or predictable, products or services are standardized, economies of scale are paramount, or functional knowledge is critical for success. Most utility companies are functionally organized.

- Matrix structure. Matrix structures combine criteria. They can be effective at processing large volumes of information.23 However, they require extensive collaboration and negotiation before reaching final decisions, and this comes at a high price in terms of lost clarity, slow decision making, and internal conflict. Their redundant systems make them costly to operate. In the late 1980s, Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) in the United Kingdom was structured as a five-dimensional matrix. Its costs escalated, while lack of innovation and slowness of decision making proved fundamental sources of competitive disadvantage. The company almost failed before new management stepped in and resolved the question “Who calls the shots?”

- Outsourcing. For activities that are essential but not central to the core mission or value proposition, the trend is to hand them off to a specialist that can enjoy economies of scale—either a central processing unit owned by the company or an external supplier. The decision to insource or outsource is often hotly contested. The British Petroleum Company (BP), for example, has gone the outsourcing route, whereas Shell has proceeded with insourcing. Regardless of outcome, the mandate is clear: reduce the costs of noncore activities while maintaining acceptable service quality.

Integration

Differentiation may create as many problems as it solves, and regardless of who does the work, a differentiated organization must be reintegrated. For example, a product-line company still has to encourage unity and cooperation—products from different divisions sold under the same company banner need to work together. Multinationals refer to this mandate as local responsiveness and global integration.24 Companies have developed a long list of mechanisms to compensate for the tendency of differentiated units to diverge.

- Hierarchy. The traditional mechanism for binding together a disparate organization is a hierarchy of supervision. A boss sets a shared direction, encourages collective performance, and resolves conflicts. But that central boss has severely limited information-processing capacity (especially in the midst of the environmental turbulence as described in chapter 2), the hierarchical infrastructure is costly, and the centralized decision making erodes commitment among employees.

- Meetings. Bringing people together for meetings may facilitate common understanding, whether in person, by phone, or by video-conference. With a clear agenda and focus, meetings enable people from different units to collaborate effectively; without focus, meetings waste endless hours and breed antagonism among the participants and for the organization. Without meetings at all, people waste endless hours doing their own thing and not learning from each other.

- Corporate staff. Accounting, finance, HR, IT, legal, and marketing staff can promote information sharing and provide common rules and processes that encourage horizontal coordination. They can also discourage it and build silos exclusively within their function if not properly guided.

- Measurement and rewards. Measurements and rewards that focus on and reinforce collective performance can promote cooperation among otherwise competing units. They require careful design, or the behaviors and performance they shape may not be what you want.

- Values, goals, and strategy. Declaring values and setting shared visions and goals can reinforce the need for teamwork, respect, and cooperation—or undercut it, if not wisely chosen and communicated honestly.

- Recruitment, promotions, and lateral transfers. Personnel moves can tell the rest of the organization what behaviors are really valued and can move people into positions that facilitate the sharing of information from one part of a company to another. When the wrong people get ahead, that sends an equally vivid but negative message.

- Cross-training. Cross-unit project work, backed up with training about activities, processes, and needs in other units, builds broad company perspectives. But such projects must add real value. Makework activities often produce cynicism and apathy.

- Best practice and information sharing. Effective mechanisms for identifying best practices and sharing information across company units build unity while enhancing the composite business. If there’s too much red tape, however, people lose faith in the process.

- Rules and roles. Rules and policies can encourage knowledge transfer and cooperation, creating roles and positions that link one department with another.25 For example, a sales engineer is part engineer and part sales rep, and works directly with both departments to communicate their respective needs back and forth. Similarly, policies can build walls where none need exist.

Configuration

HR also contributes to discussions of work configuration: the number of organizational layers, the proportion of staff to line, and locus of authority.

- Organizational layers. Companies are reducing layers and increasing span of control. This yields organizations that are nimbler and more responsive than their predecessors, with stronger quality and customer focus and a redefined management role. When Dana Corporation removed two-thirds of its management layers, for example, the remainder switched from telling people what to do to establishing shared goals, solving problems, providing information, and training, coaching, and inspiring employees.

- Corporate staff. As the workforce becomes more educated, better trained, and better informed, its need for rules and monitoring is reduced. Meanwhile, technology and outsourcing accomplish many transactional activities of traditional staff functions. As a result, staff-to-line ratios have reduced significantly.

- Locus of decision making. A central work flow question is which people at what levels get to make which decisions. In today’s leaner, faster, and more innovative organizations, decision making moves toward the front line—toward employees who know the customers best, have the most information about products and services, and understand competitive realities. Besides producing better decisions, this trend makes employees feel more valued, less likely to leave, and more committed to implementing the decisions.26 When Air Products and Chemicals reduced its corporate staff by 30 percent, frontline supervisors and employees took responsibility for improving processes, eliminating low-value-added activities, and achieving their targets.

Work Flow: The “How” Choices

Companies transmute raw materials and ideas into products and services through three sets of choices: human interaction patterns, focused governance, and levels of customization.

Human Interaction Patterns

The basic patterns of who does what, when, and with whom make a big difference in what gets produced. Depending on the desired outputs, different interaction patterns will produce optimal results.

- Individual production. Some tasks need little or no work-related interaction. Individual employees can be set to work without trying to form them into teams. Piece-rate production exemplifies this work pattern.

- Sequential production. Assembly-line production processes, where each worker does one thing to the product and passes it on to the next, who passes it on to the next, and so forth, accelerate productivity. The assembly line augments individual strength and skill with equipment and rigid procedures.

- Interactive teams. With still more equipment but flexible procedures, modern companies are applying teamwork rather than lines to large-scale assembly processes—and further accelerating productivity, lowering costs, and boosting productivity.

- Sequential teams. Sequential team production merges assembly-line production with teamwork. Teams complete substantial subassemblies and then pass the completed subassemblies to the next team. This combines the efficiency of sequential production and the integration and motivation of teamwork.

- Virtual teams. Some tasks need the skills of people who work in different units and even in different locations. With modern communications, teams can form to address these tasks, and disappear just as quickly, without their members’ meeting face-to-face for any length of time, if at all.

Focused Governance

The main choice here is between vertical functional silos and horizontal processes driven by customer requirements.

- Vertical organization. In a vertical organization, functional departments dictate effectiveness criteria. The problem is that departments take on a life of their own and can lose track of customer needs. Information tends to flow down and up the functional hierarchy rather than across functions. This occasionally results in customers and products falling between the cracks.27 Decisions come from the top of the hierarchy rather than from the levels at which customer information is most available.

- Horizontal organization. The horizontal organization begins with customer inputs and ends with customer utilization of products and services. It organizes work to fit smoothly in between. Its most influential individuals own processes rather than functions. The corporate culture places a premium on openness and collaboration. The organization reinforces this outlook with measurements and rewards for total process results, and with substantial cross-training and broad job expectations.

Customization

The next choice involves the extent to which processes are standardized or customized.

- Standardized processes. Standardized processes tend to be designed for fast order fulfillment for uniform products with few options and extensive automation. Quality is achieved through standardized service levels. Providing low-cost throughput dominates the process logic.

- Customized processes. Customized processes tailor product and process specifics through intensive interaction with customers, who derive value from the personalized output and delivery. Costs tend to be passed on to customers. A modified version offers the assembly of customized units out of standardized parts.

Work Flow: The “Where” Choices

Physical space communicates explicit and implicit messages about what matters to an organization.28 HR professionals’ expertise in culture, productivity, and employee value propositions can be useful in discussions with facility managers and architecture and design specialists. Physical settings may shape culture and increase productivity through facilitating the flow of work, engaging employees, and sending powerful signals about values, leadership, and status.29

Space

The arrangement of walls, seating patterns, and meeting rooms have direct influence on the flow of work.

- Modularity. Modularity enables organizations to reconfigure space quickly and flexibly depending on business needs. For example, conference rooms can become temporary offices or house task forces assigned to a project. SEI Investments has taken this to its logical conclusion, eliminating interior walls and cubicles. Each employee has a suite of furniture on wheels. When teams form, members roll their “offices” into a clump, plug in their voice and data ports, and go to work.

- Physical proximity. Proximity encourages trust and enhances the flow of information. If you want closer cooperation between sales and engineering, put their offices next to each other. If you want to boost creativity among your innovative “sparkplugs,” move them near each other. Pixar, the computer animation studio, recently consolidated its staff in one building to facilitate greater synergistic creativity and collaboration.

- Meeting rooms. Space and furniture in meeting rooms speak volumes about expectations: a U-shaped table implies a two-way dialog between presenter and participants, while a round one implies team problem solving with influence based on personal insight. Or consider flip charts and overheads versus LCD projectors—the former encourage interaction, the latter passive listening.

- Customer contact. If you want employees to know what customers need, put them where they see customers. GE Aircraft Engines, for example, locates many of its service personnel in its customers’ facilities.

Environment

Physical setting influences the motivation and productivity of individual employees.

- Lighting. Natural lighting in office space helps people connect with the world outside the office and prevents the irritation caused by long sessions in closed rooms. (We often see this in seminars; after a few days in a hotel ballroom, participants become edgy—without knowing why. After a half day of training outside, they generally revive.) However, glare makes effective lighting for computer-based work a particular challenge. Four types of lighting may be used in the office environment:30

- Daylight from windows, skylights, and glass doors

- Ambient light from ceiling or furniture-mounted light sources

- Task light from lamps focused on a particular area

- Accent or display lighting to add visual interest and define space

- Color. Color evokes mood and action. Some companies pick light colors for an open feeling; others equate social status with darker colors. Red, orange, and yellow tend to stimulate and excite. Pale greens, light yellows, and off-white (think doctors’ offices) tend to calm. Watercolors seem cool, fire colors seem hot by association. Whatever color you choose, there’s a message.

- Involvement. Humans tend to be strongly territorial. People like to personalize their work space. Even in temporary “hotelling” offices where employees share space and furniture, some personal touches appear. Companies that ban personalization not only reduce ownership in office space, they also risk reducing ownership in the company as a whole.

- Ergonomics. Attention to the physical demands of work pays off, both in a healthier workforce and reduced workers’ compensation claims and in increased morale. Seating and working surfaces that fit the individual worker may be more costly than one-size-fits-all office furniture, but it can pay for itself in workers’ comp alone—where back pain amounts to almost a quarter of the claims and a third of the dollars spent.31 Simply encouraging employees to move around during the day rather than spend unbroken hours at their desks can make a difference.

The physical work environment can even serve as a vehicle for attracting and retaining key talent.

Symbolism

Because of the durability and relative costliness of physical things in the working environment, people tend to attribute symbolic meaning to physical stuff. Companies intentionally and sometimes unintentionally signal powerful messages through physical symbols.

- Physical setting signals values. The first impression sticks: a traditional stone chalet in a forest communicates a different message from a modern glass office building in the downtown. The whole physical plant—architecture, location, landscaping, signage, maintenance—will be read as an indication of the company’s values. “No message” is also a message.

- Physical setting signals leadership style. Office layouts communicate management style and culture more clearly than any speech or culture change program. A top-floor corner office communicates a different leadership approach from a bottom-floor office near the main entrance. We know one leader who sits behind a desk that takes up almost half his office—and another who had the desk removed entirely and works at a small table in one corner. The former meets visitors across an imposing barrier; the latter turns and interacts directly with his guests.

- Physical setting communicates the value of people. Is the workplace clean, freshly painted, and safe? Are the gardens kept up? Are the windows clean? These tangible details of the workplace signal management’s commitment to employees.

- Physical arrangements communicate status. Larger offices, customized wall hangings, plush carpets, richness of paneling, and office location send powerful messages that fit the needs of hierarchical organizations very well. Retaining such physical accoutrements in a theoretically flat and agile organization sends the unintended message that influence is a function of position rather than a function of insight, information, and contribution.

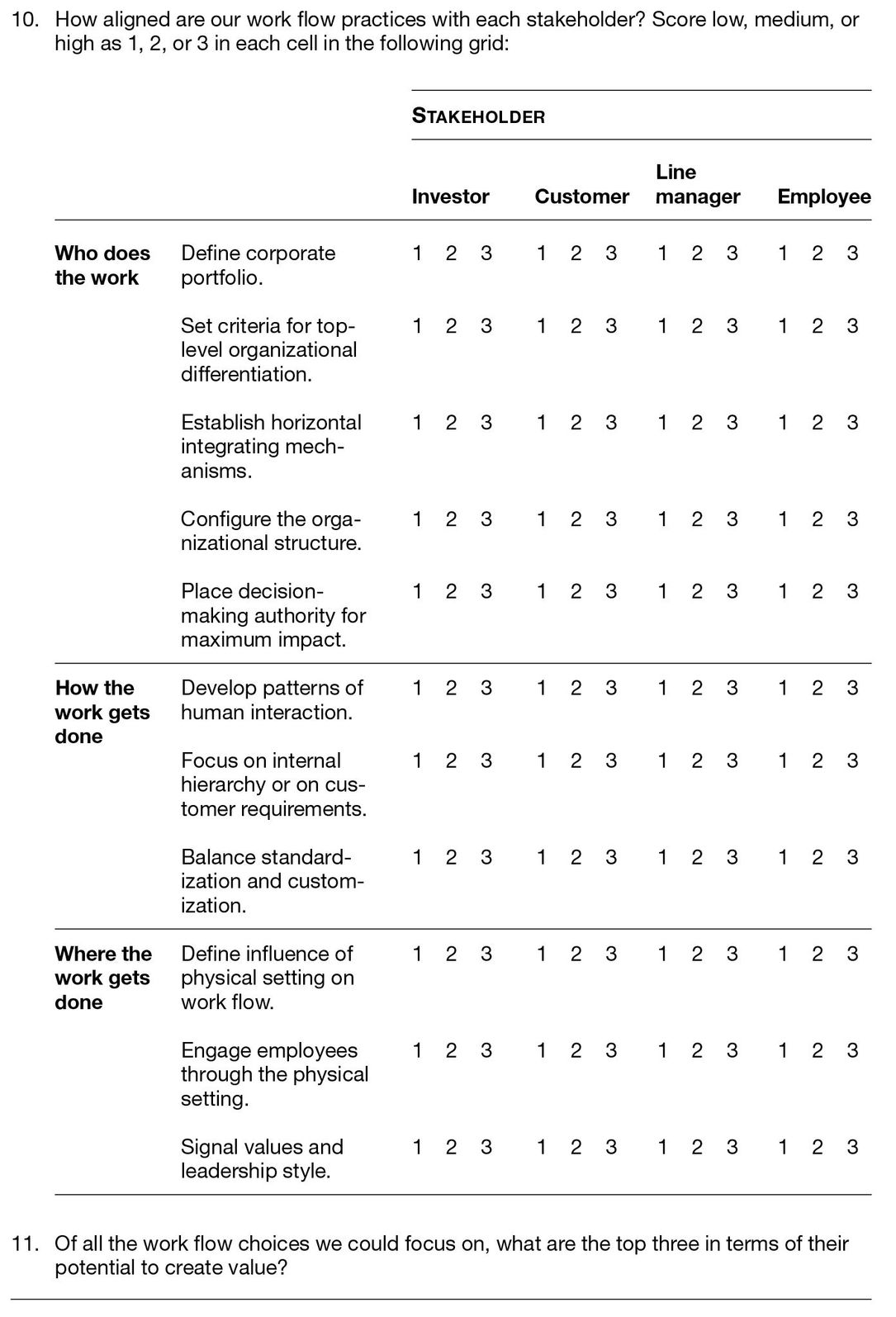

Action Plan for Flow of Work

When you address work flow, select between two and four HR practices to focus on first. The audit shown in assessment 6-3 will guide your attention to the types of practices likely to have the biggest payoff. You can then build an action plan by following the template given back in exhibit 5-1 in chapter 5.

ASSESSMENT 6 - 3

Audit for work flow

Menus for Information and Work Flow

For any company, information and work flow represent an intrinsic part of the value proposition. They have great influence on organizational capabilities and determine much of the human experience at work. Many HR professionals are beginning to add value in these areas. Now is the time for them to expand their roles by contributing even more to these important emerging HR activities.