3

External Stakeholders

Investors and Customers

IMAGINE THIS: Dan Bennett returns from an HR conference full of ideas for a new initiative (in performance management, say), assembles a task force, and implements the program companywide. After some initial resistance, the ideas take hold, and the program becomes part of the way HR does its work. Dan declares victory, and the design team delightedly moves on to the next new thing. Sounds ideal, doesn’t it?

When we tell this kind of tale, people tend to snort and say, “Nothing ever goes that smoothly.” True, we say, but even if it did, would it be a success story? And the answer we get is generally yes.

We disagree. Dan’s adventure is an ideal case of a false positive, something that sounds successful but is at best incomplete. The success of an HR initiative should be measured not by how well its design and implementation go but by what the initiative does for the organization’s key stakeholders. HR actions create value only when they create a sustainable competitive advantage.

As discussed in chapter 1, competitive advantage comes from the marketplace. Sales or research and development (R&D) creates competitive advantage when customers buy your product. Improvements in logistics or technology become a competitive advantage when customers notice benefits in cost and service—and buy your product. And you have proof of competitive advantage when increased revenue translates to increased share price.

In a boundaryless and borderless world, what happens inside an organization—HR included—must connect with what goes on outside. Changes in HR can help create employee commitment, which in turn creates customer commitment, which in turn boosts financial results. This finding has been replicated in many companies and industries (Sears, GTE, Cardinal Health, IBM). Internal focus may lead to efficiency but not effectiveness. McDonald’s may continuously improve its production of hamburgers and french fries, but all the efficiency in the world will not create competitive advantage for hamburgers and french fries if consumers are shifting toward healthier food.

HR work should likewise be judged, in part at least, by the outcomes it creates for external stakeholders. By creating a line of sight from its practices to external stakeholders, HR makes itself more relevant. HR professionals who look outside first can then tailor their actions to results that matter to two primary external stakeholders: investors and customers.

Investors and HR

Investors ultimately care about total shareholder return or market value. For publicly traded firms, the stock price represents how investors value both current and future earnings. For public agencies, privately held firms, and nonprofits, external value is harder to specify but still measurable via bond ratings, donation levels, and political goodwill. We focus on publicly traded firms in showing how HR should add value for investors, but similar arguments could be made for any organization. HR professionals can take six actions to link their work to stakeholder value:

- Become investor literate.

- Understand the importance of intangibles.

- Create HR practices that increase intangible value.

- Highlight the importance of intangible value to total shareholder return.

- Design and deliver intangibles audits.

- Align HR practices and investors’ requirements.

In taking these six actions, HR professionals move out of their comfort zones and partner with other staff experts. For example, in linking organization actions to investor results, HR teams up with those in investor relations to prepare materials for the investor community. When they invite investors to participate in HR practices, they need to understand investor expectations and show that investor understanding of HR practices will help investors make more informed investment decisions. Weaving HR into investor relations starts with becoming “investor literate,” so that those in investor relations trust the HR professional to engage appropriately with investors.

Investor Literacy

For HR professionals to deliver value to investors, they must first learn who is investing in their organization—and why. Consider this investor literacy test:

- Who are your five major shareholders and what percentage does each of them own?

- Why do they own your stock? What are their investing criteria (i.e., dividends, growth, and so on)?

- What is your tangible value? And your intangible value?

- What is your price/earnings (P/E) ratio for the last decade, and how does it compare to your industry average and to the firm with the highest P/E ratio in your industry?

- Who are the top analysts who follow your industry? How do they view your company compared to your competition?

Few senior HR executives can answer all these questions—and we’ve asked them many times. Yet these questions form the base of knowledge that will enable HR professionals to link their work to investor value.

Investor literacy also includes attention to corporate governance. With corporate malfeasance increasingly drawing media and legislative attention—and investor ire—HR professionals should be aware of governance processes within the firm. This includes knowledge of legislation like Sarbanes-Oxley, which prescribes board and leadership behavior, and assessments like that from Institutional Shareholder Services, which rates corporate governance. But it also includes focusing on how well your board governs itself on processes essential for good board governance, such as managing dissent, reaching consensus, and focusing on the right issues.

The Importance of Intangibles

Firms with higher earnings ought to have higher stock prices. This intuitively sensible proposition has led to rigorous standards in codifying and comparing earnings (as in the policies of the Financial Accounting Standards Board and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission). But the situation is changing. Accounting professors Baruch Lev and Paul Zarowin at New York University report that the regression between earnings and shareholder value was between 75 percent and 90 percent from 1960 through 1990.1 That is, 75–90 percent of a firm’s market value (stock price times shares outstanding) could be predicted by its financial performance. Since 1990, however, this figure has dropped to about 50 percent in both up and down markets—meaning that half the market value of a firm is not directly tied to present earnings. Instead, it is tied to what the financial community calls intangibles. Intangibles represent value derived from choices about what happens inside the firm and from how investors value those decisions, rather than from its physical assets.

Intangibles can be observed outside business. Successful sports teams have them: the quality of coaching, the ability to win, and the like. Restaurants have the setting, reputation, and atmosphere of committed service. Government agencies have political goodwill and access to political support and budget allocations. For any organization, intangibles are the perceived outcomes of specific actions.

It is all too easy to focus intangible value on what is easy to measure—investments in R&D, technology, or brand—but that leaves crucial intangibles, involving investments in organization and people, under the radar. Organizations and people become intangible assets when they give investors confidence in future, tangible earnings, and this is an area where HR can make a major contribution.

Support for Practices That Build Value

With the intent of making intangibles tangible, we have proposed a pattern of techniques that increase organizational intangibles, beginning with the basic essentials at level 1 and proceeding to more complex concepts. We call this the architecture for intangibles, as illustrated in table 3-1.2

Architecture for intangibles

| Level | Area of focus | Action potential |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Keep your promises. | Build and defend a reputation among external and internal stakeholders for doing what you say you will do. |

| 2 | Imagine the future while investing in the present. | Define growth strategy and manage trade-offs in customer intimacy, product innovation, and geographic expansion to achieve growth. |

| 3 | Put your money where your strat egy is. | Provide concrete support for intangibles by building core competencies in R&D, sales and marketing, manufacturing, and the like. |

| 4 | Build value through organization and people. | Develop capabilities of shared mindset, talent, speed, collaboration, leadership, accountability, learning, and the like throughout the organization. |

This architecture is progressive and sequential. And at every level, HR practices can be integral to success—helping leaders behave in ways that engender trust and promote learning and communication among internal stakeholders, making them more likely to behave in ways that engage and delight external stakeholders.

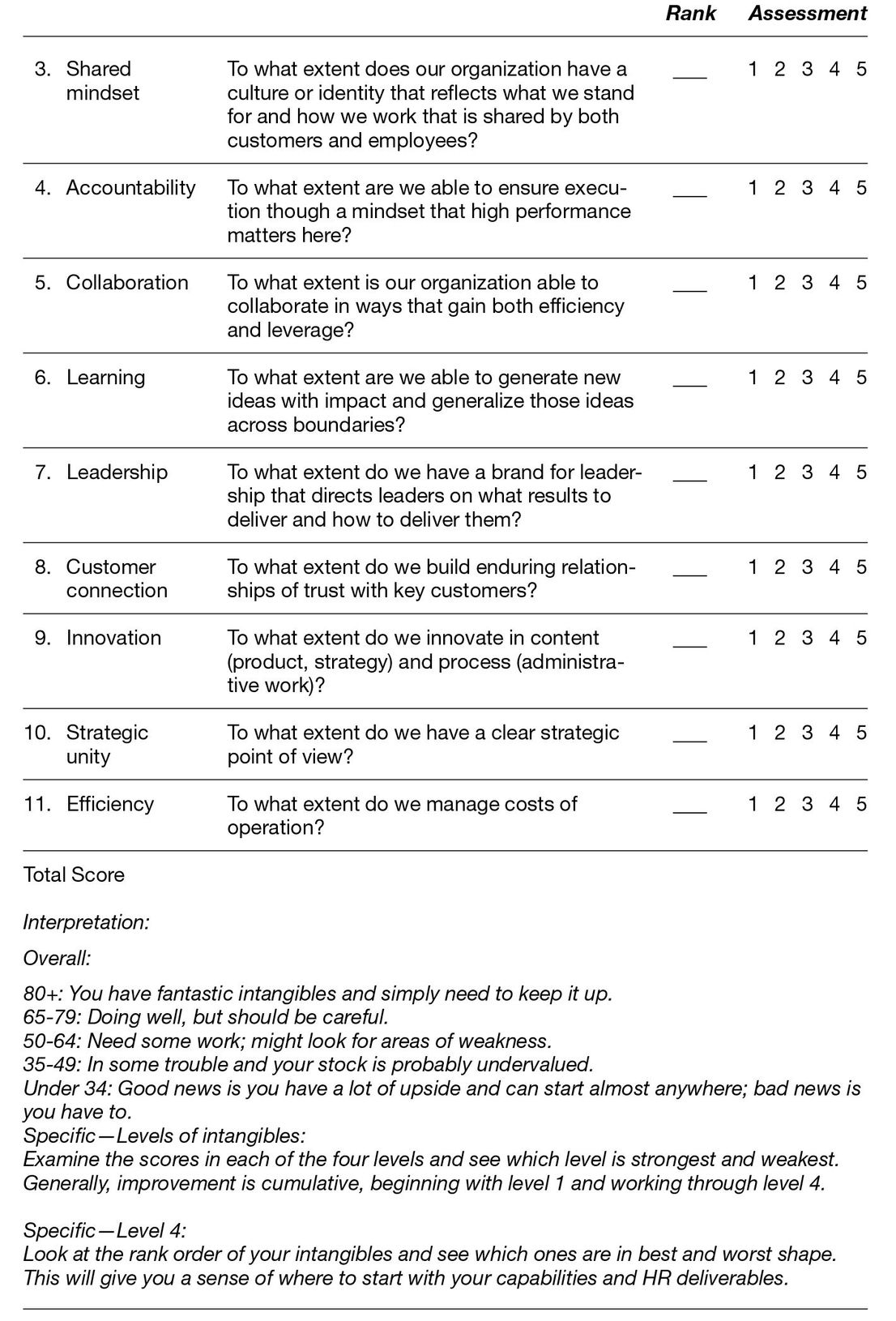

But HR really adds value at level 4 by defining and creating capabilities as intangibles. This shifts HR from a focus on just people to organizations where people work. Traditionally, organizations have been characterized by their visible hierarchy and structure or by their work processes. Recently, however, the study of organizations has shifted focus from structure and processes to capabilities.3 Organization capabilities represent the capacity of an organization to use resources, get things done, and behave in ways that accomplish goals. They characterize how people think and behave in the context of the organization. They form the organization’s identity or personality. Capabilities define what the organization does well and, in the end, what it is.

Organizations can be viewed as bundles of capabilities—and not just by researchers. External stakeholders and even casual observers see the same things. When we ask people to identify firms they admire, we often hear names such as Microsoft, Nordstrom, or GE. We then ask how many layers of management each firm has—and (unsurprisingly) no one knows or cares. But when we ask the reasons for their admiration, people quickly pinpoint capabilities such as the ability to innovate or to deliver high-quality customer experiences. These responses capture the transition from the age-old adage “structure follows strategy” to “capabilities follow strategy.” With this logic, an effective organization is defined less by structure than by the capabilities that enable it to respond to business demands.

An organization’s capabilities are the deliverables from HR efforts. These capabilities enhance (or reduce) investor confidence in future earnings and increase (or decrease) market capitalization. HR professionals who link their work to capabilities and who then find ways to communicate those capabilities to investors deliver shareholder value. Mark Huselid, Brian Becker, and Richard Beatty found that firms with speed, talent, learning, shared mindset, innovation, and accountability capabilities significantly outperformed lower-capability firms in productivity, profitability, and shareholder value.4

Firms differ so much that no one can produce a magic list of universally desirable or ideal capabilities. However, table 3-2 captures a subset of capabilities that do seem to be inherent in well-managed firms.5

Clearly, qualities such as efficiency, collaboration, talent, and speed are not the only capabilities an organization may require, but they illustrate the types of capabilities that make intangibles tangible. They delight customers; they engage employees; they establish reputations among investors; and they provide long-term sustainable value. HR professionals should be architects and thought leaders in defining and creating each of these capabilities.

Education in the Value of Intangibles

Intangibles need to be presented in the financial terms that leaders understand. Here are three visual exercises that highlight the importance of intangibles and spotlight HR’s impact on shareholder value.

Earnings and Shareholder Value

To put the whole question of intangibles in context, go through the last ten or fifteen years of your firm’s results and plot (1) earnings and (2) stock price (or total market capitalization) by quarter. This chart will show whether market value is above or below the earnings line—that is, whether the firm has a net positive or negative intangible reputation.

Capabilities of exemplar companies

| Capability | Definition | Exemplar company |

|---|---|---|

| Talent | We are good at attracting, motivating, and retaining competent and committed people. | Hitachi |

| McKinsey | ||

| Microsoft | ||

| Speed | We are good at making important changes happen fast. | Dell |

| Samsung | ||

| Toshiba | ||

| Shared mindset | We are good at ensuring that customers and employees have positive images of and experiences with our organization. | Harley-Davidson |

| Nordstrom | ||

| United Bank of Switzerland | ||

| Accountability | We are good at the disciplines that result in high performance. | Continental Airlines |

| Honeywell | ||

| Total | ||

| Collaboration | We are good at working across boundaries to ensure both efficiency and leverage. | BP |

| Ericsson | ||

| Time Warner | ||

| Learning | We are good at generating and generalizing ideas with impact. | BAE |

| Toyota | ||

| Unilever | ||

| Leadership | We are good at embedding leaders throughout the organization who deliver the right results in the right way—who carry our leadership brand. | Cathay Pacific |

| General Electric | ||

| Hewlett-Packard | ||

| Customer connection | We are good at building enduring relationships of trust with targeted customers. | Harrah’s |

| Marriott | ||

| Nippon Telegraph & Telephone | ||

| Innovation | We are good at doing something new in both content and process. | 3M |

| Herman Miller | ||

| Intel | ||

| Strategic unity | We are good at articulating and sharing a strategic point of view. | Hallmark |

| ICICI Bank | ||

| Efficiency | We are good at managing costs of operation. | SKF |

| Southwest Airlines | ||

| Wal-Mart |

Price/Earnings Ratio Race

How do your firm’s intangibles compare to those of your competition? For ten or fifteen years’ worth of results, plot your firm’s quarterly P/E ratio against that of your most successful competitor. This trend line offers an overall report card on how investors perceive your firm and its leading competitor. Once when we tried this, we found that a firm had a P/E ratio consistently 20 percent below that of its largest competitor. Investors were less confident in the firm’s management team than in the competitors’, and the gap persisted over time. This firm’s market value was about $20 billion at the time, implying that reputation had cost the firm about $4 billion. The management team did not like the insight, but they could not run away from it.

Management View of Impact of Organization and People

Sometimes, making leaders’ assumptions explicit helps frame a dialogue on HR and shareholder value. Give each member of the top management team a blank graph showing shareholder value on one axis and quality of organization and people (HR) on the other. Ask each member of the management team to plot their assumptions. Share the responses and talk about the implications of the slopes of the lines. Some will have a flat line (regardless of HR quality, shareholder value does not go up), but more often we generally find ratios in the 3:2 or 2:1 range (every three points of organization results in two points in shareholder value). With this data, you can lead a discussion about how much HR issues matter in leaders’ perceptions of shareholder value. Without having to “prove the case,” leaders implicitly believe that increasing the quality of people and organization will lead to shareholder value.

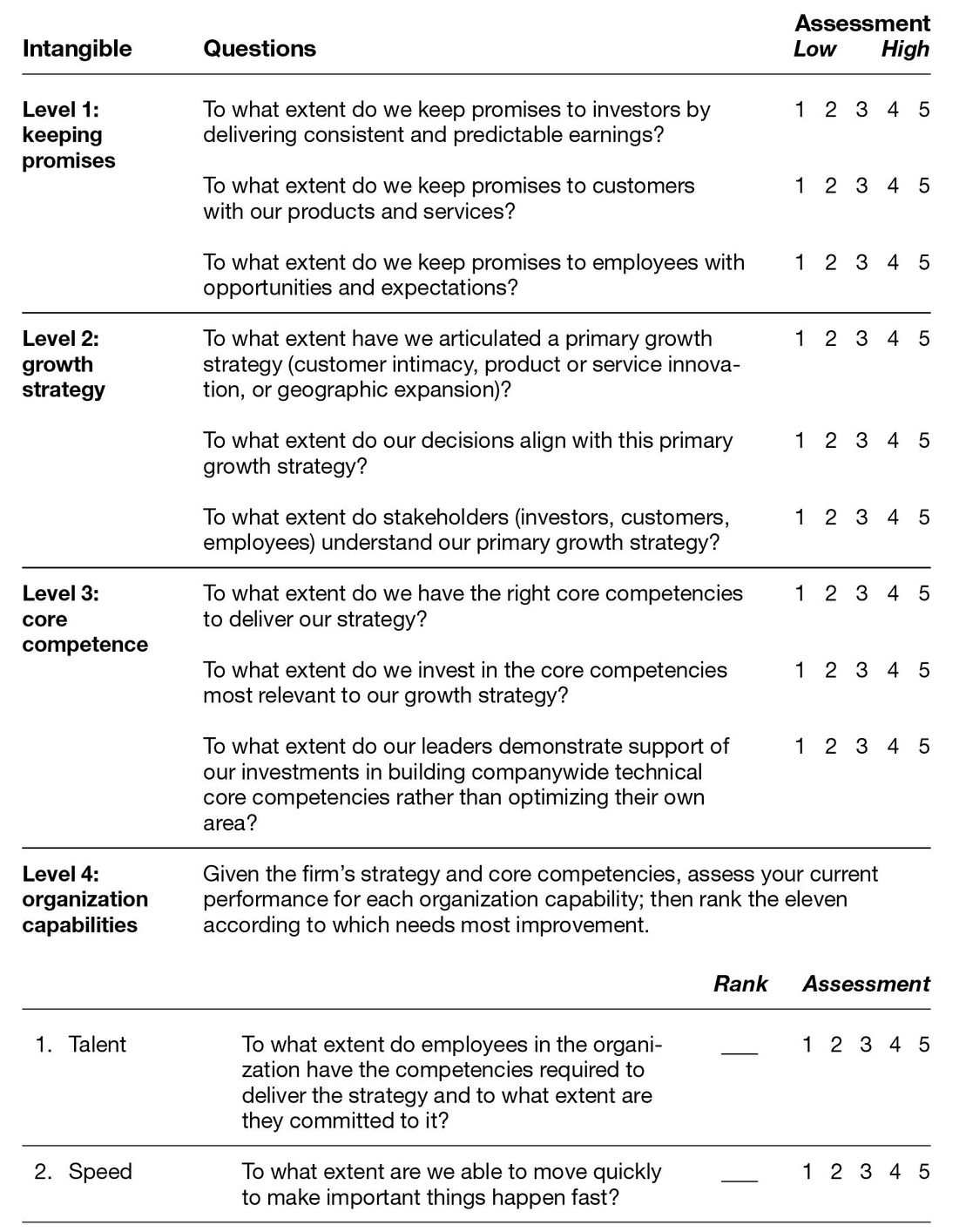

Intangibles Audits

An intangibles audit assesses what is necessary to deliver investor value given an organization unit’s history and strategy, measures how well intangibles are being delivered, and leads to an action plan for improvement. Assessment 3-1 shows a sample template for an intangibles audit (for more information, go to http://www.rbl.net/Survey/intangibles.html). This self-assessment tool helps HR leaders evaluate their organizations on four core dimensions: (1) keeping promises, (2) growth strategy, (3) core competence, and (4) organization capabilities covering eleven possible strengths. Many organizations have adapted this template with productive results. HR professionals can be the prime mover for these audits as they collaborate with other staff experts and prepare information for business leaders.

ASSESSMENT 3 - 1

Intangibles audit

Directions: Select an organization unit (plant, division, region, zone, business, company) and answer the following questions.

Interpretation and Use

To perform an intangibles audit, go through the following five steps:

- Decide whether the audit should occur in the entire organization, a business unit, region, or plant. Remember that although HR can architect the audit, the unit leadership must own and sponsor it. For example, if you want to audit the entire company, you need the board of directors or senior executives to sponsor the effort. HR would seldom do an intangibles audit without support from business leaders and collaboration of other staff experts.

- Create the content of the audit (i.e., the dimensions to be audited). Assessment 3-1 lists generic questions that describe each of the four levels of intangible value. Recast these questions into words and phrases that will make sense to people in the organization. Involve those from other staff functions like finance to help you tailor the questions to your organization.

- Collect data on the current and desired status of the intangibles being assessed. This information may be collected by degrees:

- 90 degree. Collect data from the leadership team of the unit being audited. This gets quick results but is often deceptive; the leadership team’s self-report may be biased.

- 360 degree. Collect data from many groups within the company. Such assessments can tell very different stories, depending on how each group sees the information.

- 720 degree. Collect information not only from inside the company but from outsiders: investors, customers, suppliers, or regulators. These external groups matter because they are the groups who ultimately determine if the organization has intangible value.

- Synthesize the data to identify the intangibles requiring managerial attention. Create a summary score by averaging the items for each of the four levels to determine your performance at each level. Scores 4–5 suggest that you are doing a good job and need to be sustained; 3 means that you have areas to work on; and 2 or below indicates that your intangibles are detracting value. Look for patterns in the data: for example, do all rating groups consistently rate you low in one area? Pick action items that require leadership attention to deliver strategy goals. Identify which intangibles will have the most impact and be easiest to implement.

- Share the results with investors. The report will give investors confidence not only in past and present earnings and in the firm’s ability to produce future earnings, but also in the firm’s ability to be self aware. HR professionals who design and deliver these intangibles audits add value for the investment community. Initially, peers in other departments may be hesitant or resistant, but when they see that this information helps create investor confidence, their concerns will turn to support.

Alignment Between HR and Investor Requirements

Traditionally, HR practices focus on dynamics inside the organization. When HR professionals take investors’ desires into account, their practices can develop a more value-focused meaning. In the next few sections, we suggest ways that HR practice might align with investors. Selecting one or two ideas from the following illustrations might become a starting point in building investor-focused HR practices. Again, these practices would be crafted by partnering with staff experts who know and understand investor expectations and behaviors.

Investors and Staffing

What if the investors could vote on individuals hired or promoted in the firm? In some limited cases, investors do so through the surrogate voice of the board. But what if some of the large institutional investors actually participated in interviews for senior officers? What questions would they ask? What leadership and management qualities would they look for? What types of individuals would convince them that the management team was able to make correct decisions? Or, alternatively, what if institutional investors reviewed competence models used as candidate screens in the hiring process? Would an institutional investor focus on the same attributes as the traditional hiring manager? Or would the interview questions be different?

HR professionals should seek ways to engage targeted investors in hiring and promotion decisions. Using investor criteria and participation in the staffing process brings a rigor and discipline that is often overlooked. In addition, if investors participate in the selection of the management team, they may be more committed to this team’s decisions and choices.

Investors and Training and Development

Assume someone representing your largest single investor sat through the last five-day leadership program your firm offered. What would be their investment response (buy, hold, sell) at the end of the week?

This question imposes a new filter on what is taught, how it is taught, and what participants in training leave with at the end of the week. We predict that most investors would be more positive if participants focused on real business issues within their firm rather than case studies of other firms; faced competitive realities in candid conversation; and, as a result of the training experience, left with a vision of clear and specific actions to take. That sort of training would show investors that the leadership team knows what needs to be done, understands strategic choices, and is willing to make and implement bold decisions. In addition, we predict that investors would relish candid dialogue and disagreement before reaching consensus on what to do. Many of the training dollars currently spent would not lead to “buy” recommendations, because the link between training activities and business results is obscure at best.

Investors and Appraisal and Rewards

Many firms already tie management behaviors to investor-focused rewards. Putting a larger percentage of total compensation into stockbased incentives (grants, options, and the like) links management actions to investors. Many claim that CEO pay relative to average employee pay is excessive. Such arguments are less tenable when CEO pay is linked to long-term stock price. The boundary between managers and investors is removed when managers become investors through stock ownership programs. In addition, the wider and deeper the investment mindset throughout a firm, the more managers act and think like investors.

We had a chance to work with a firm going through a leveraged buyout. To keep their jobs, managers were required to invest from $100,000 to $5 million cash in the new firm. The changes in mindset and action patterns were dramatic. The new owner-managers stopped flying three people to visit a customer when one would do. Instead of holding conferences at five-star hotels, they used company facilities. Instead of making visits to plan visits, they used phones and faxes for preliminary work. Literally thousands of decisions were made differently under the new regime. When managers act as both owners and agents, they respond differently.

Institutional investors might examine the firm’s compensation philosophy and practices. In theory, board members act on behalf of the owners, but institutional investors might become more active by reviewing standards set in performance appraisals, compensation practices used to change behavior, and feedback mechanisms used to share information.

Investors and Governance and Communication

Investors in publicly traded firms have traditionally been hands-off. They do not participate in teams, help develop processes, or set and accomplish strategies. However, when investors realize that the intangibles predict as much of the shareholder value as financial performance does, their interests may change. They will start looking at how well the organization makes decisions, allocates responsibilities, and meets commitments. Peter Lynch, the savvy and well-known investor, has suggested smart investors recognize firms that provide customers what they want (such as Toys “R” Us).

As these and other HR practices are applied through an investor filter, investors gain confidence in the organization’s ability to deliver future earnings.

Customers and HR

Keeping a customer is more profitable than attracting a new one.6 With ever-expanding global competition, however, today’s customers tend to be both demanding and exacting, so keeping them requires ongoing, across-the-board attention.

Long-term customer loyalty to a product or service develops as people have consistently positive experiences with the firm and as the firm meets their expectations. If their expectations are not met, continued loyalty depends on whether problems are resolved quickly.7 The customer experience is often based on perceptions of reliability (dependability and accuracy), responsiveness (promptness of service), assurance (trust and confidence), empathy (personal care and attention), and presentation (appearance of facilities and personnel).8 All these perceptions derive from employee behavior, and that means that all are opportunities for HR to contribute to the bottom line. We suggest five specific things HR professionals know and do to improve customer experiences:

- Develop customer literacy.

- Think and act like a customer.

- Measure and track the firm’s share of targeted customers and the customer value proposition.

- Align HR practices to the customer value proposition.

- Engage target customers in HR practices.

In connecting with customers, HR does not replace marketing and sales, but collaborates with them. HR translates customer expectations into employee behavior, which helps meet and exceed those expectations. As such, marketing research is not just about the nature of the market, but about how to respond to the market. When HR knows customers, they can help with that response.

Develop Customer Literacy

Some customers—to echo Orwell’s telling phrase—are more equal than others. This is obvious, but few HR professionals can identify which customers matter most to their employers. Customer literacy begins with knowing the customers and their buying criteria. Which customers represent 80 percent of your firm’s revenues and profits? These are the target customers who should be the focal point of your firm’s activities. They are the customers whose loyalty and intimacy you want. They should be uppermost on the mind of every employee.

Once the target customers are known, it is critical to determine their buying criteria. Why do they purchase from you as opposed to your competitors? What is unique about your offering that consistently attracts target customers? What combination of service, value, reputation, product features, innovation, or quality keeps them coming back? HR professionals are ideally placed to find and present this information, along with equally interesting information about what employees in various departments think customers want.

This kind of information allows a firm to turn customer buying criteria into visible actions that customers will experience. Once employees know what customers value, they can concentrate on those values, which, in turn, makes customers more likely to have a positive experience. At Burger King, for example, HR identified purchase criteria, then turned these ideas into specific behaviors that customer contact employees should master. Employees show customer friendliness by smiling, maintaining eye contact, and saying thank you. They anticipate customer needs by providing extras before being requested, by taking corrective action on the spot, and by running the express line at busy times. They monitor quality of service by filling each order in less than three minutes. Customer criteria become employee behaviors.

HR professionals should be able to pass a customer literacy test with questions such as:

- Who are the five major buyers in the markets you serve?

- Who are your firm’s five major customers?

- If the market includes major potential customers who do not buy from you, why not? What is the customer value proposition of your competitor that attracts and keeps these customers?

- Why do your target customers buy from you? What are their buying criteria?

- What do your potential target customers like better about your competitors than about you?

- How do you ensure that your target customers have a positive customer experience?

- What do you do to build connectivity or intimacy with your target customers?

Knowing this information allows you to collaborate with customer contact personnel.

Think and Act Like a Customer

Customer literacy defines who the customers are and why they are buying from you. A positive customer experience ensures that they will continue to buy from you. For HR professionals to fully appreciate customer experience, they must learn to think and act like customers. Ask yourself, If I were a customer of this business, would I like being treated the way we treat our customers? If I were anticipating a purchase and could choose among several vendors, would I pick my firm?

Now think like a competitor—what are the weak links of this firm’s offering that a rival would go after? By asking what-if questions, an HR professional can begin to imagine the firm through the eyes of a customer. This will lead to better customer experiences and increase the likelihood that they will continue to buy from you.

To fully see the firm through the eyes of customers, it is important to put yourself in the customers’ shoes. Buy your own firm’s products without telling anyone where you work. Attend trade shows where you can talk with customers or go where customers buy products and watch them in action. Use competing products to see how customers fare with them. Join sales reps for their calls on key accounts. Activities like these probably aren’t in your job description or within your expectations, but they will help you see what your firm’s customers really care about. They will also bond you with customer contact people who may be hesitant to involve HR in customer relations.

Measure and Track Customer Results

Customer share—the proportion of the target customer population buying from your firm and not from your competitors—is replacing market share as the key measure of success. It provides a direct indicator of your firm’s reputation among its best customers—and it doesn’t just happen. Instead, it is driven by relationship management with targeted customers. And HR professionals have the ideal skills, background, and position to assist in developing these relationships. By encouraging organized steps designed to ensure that target customers have a positive experience with the firm and then tracking and reporting the results, HR professionals can have a direct positive impact on customer share and ultimately, on the bottom line.

Up-Selling and Cross-Selling

Gaining customer share means selling additional products and services to existing customers within the domain of the firm. For example, Disney cross-sells products in its theme parks and stores—that is, employees in the theme parks recommend Disney products, and employees in Disney stores recommend Disney theme parks. HR professionals charged with orientation and training can help employees know and discuss the array of products offered by a firm and help them understand how to sell its full range of products or services.

Constant Customer Feedback

To please customers, employees need to know how customers react to their experience with your firm. HR can step in and work with marketing specialists to help develop ways to identify, gather, and distribute concrete customer data. At one retail chain, for example, HR was part of the team that designed a system to track customer experience by asking purchasers these questions:

- Overall, how satisfied were you with your shopping experience?

- How reliable was the employee who helped you?

- How responsive was the employee who helped you?

- How much empathy did the employee who helped you demonstrate?

These items then formed an index of overall customer satisfaction. In addition, each sales receipt identified the employee who worked with the customer, and the retailer prepared a monthly customer experience score for each employee. Despite occasional efforts to bias the results (by urging customers to give positive answers), the index provided useful information on employee performance. For the first six months of the system’s operation, the data was simply shared with employees each month; then it became part of the formal performance review system.

Another firm asks executives to work a couple of hours a month at the 1-800 service call center. Participating executives not only see summaries of call data but actually answer calls, giving them a firsthand sense of the patterns of customer responses. Other mechanisms for creating a constant flow of customer feedback include mystery shoppers in retail, customer follow-up surveys or phone calls, and customer focus groups.

HR professionals can participate in the design teams for all these types of customer feedback efforts. In the process, they should pay particular attention to how the customer data translates into changes in employee behavior patterns and corporate policies.

Tailored Customer Value Proposition

Mass customization gives each customer a personal value proposition. For example, by combining size and style variants, Levi Strauss has about 1.5 million options for a pair of pants. The company makes it possible for customers to order based on their own measurements and style choices rather than choosing from the necessarily limited selection of ready-made product, boosting their chance of having pants that fit and look the way they want. As a result, they are more likely to buy most of their current and future pants from Levi Strauss.

HR professionals can help create a mass customization mindset through communication programs about the importance of tailored customer service; by monitoring customer data and making sure it translates into employee behavior; and by designing customization into performance management programs.

Employee Accountability for Customer Share

When each employee feels responsible for customer share, customer share goes up. HR programs should include the satisfaction of target customers as one of the indicators of employee performance. In addition, they should offer rewards and recognition for outstanding employee service. The more effective these measures are in getting the message across, the more powerfully they will instill accountability for customer share.

Align HR Practices to the Customer Value Proposition

The best HR practices are the ones designed to meet the needs of customers and ensure that they have a positive experience. That is, HR needs to make sure that the firm’s employee selection, development, reward, and communication programs all work to encourage the skills needed for customer satisfaction. Such HR practices will build customer loyalty over time (see chapters 5 and 6 for details of these HR practices).

Staffing and the Customer Value Proposition

We once asked a senior executive team, “If the customers could hire twenty officers to run the firm, would they be willing to hire the twenty of you?”

Someone answered, “How could they do that? They don’t know who we are.”

We suggested they think about this comment, pointing out what was going on inside the firm might not be well enough connected to what was going on outside it. Customer values, after all, should permeate all phases of talent flow, beginning with the criteria for hiring and promotion. What would a customer want to see more of or less of in behaviors of employees in the firm? What skills, values, and norms would customers want key employees to have? If the criteria that brought the executive group to their current positions included the things that target customers value, then, yes, they could all be reasonably sure that the customers would find them acceptable.

Training and the Customer Value Proposition

If customers attended a training event, how would they feel about the content being taught? Would they say that the training event helped employees gain value-adding skills? Would they be willing to pay for the event? In essence, customers do pay for training, albeit indirectly. Yet too often, training and development experiences are created without careful consideration of customer criteria.

Measures and Rewards and the Customer Value Proposition

Standards for what employees should be, know, do, and deliver need to reflect customer expectations and enhance customer experiences. Too often, however, standards are focused inside and not outside the organization. If customers were to review one of your firm’s performance appraisal forms, how would they react? Would meeting the explicit standards and measures mean that employees will have provided good customer experiences?

Rewards can also be aligned to customer expectations. Employee bonuses, for example, may be tied to customer experience ratings (loyalty, satisfaction, customer share). And don’t limit the process to financial rewards; nonfinancial rewards may well have more lasting impact. For example, consider allowing customers to honor exceptional employee service—as defined by the customer.

Communication and Governance and the Customer Value Proposition

The best brand is the one that works both inside and outside the company, sending consistent messages about what the company stands for. One high-tech firm went so far as to encourage employees to share its core values with target customers—integrity, respect for individuals, teamwork, innovation, and contribution to customers and the community. That may sound somewhat generic, but the firm also encouraged employees to ask customers to define what employees should do to embody these ideals—and to bring the replies back so that procedures could be designed to accommodate them. The quality of employee and customer communications may be measured by the percentage of both employees and customers who feel that the company hears and responds to their needs.

Governance (i.e., how the organization is organized, allocates resources, and makes decisions) should also be tailored to customer requirements. Some customers want a single contact point; others prefer being able to work with each subunit of the firm separately. Likewise, some customers will want (and pay for) personal contact; others will be more comfortable with an online interface. Ideally, a firm should be responsive to differences in individual customer preferences.

And in each of these cases, HR practices should reflect and reinforce target customer value propositions. As the keeper of the system, HR is ideally placed to institutionalize customer value into the organization.

Engage Target Customers in HR Practices

Commitment often follows action. By including targeted customers in HR practices, HR professionals can increase customer commitment to the firm. This effect is so powerful that it hardly matters what the content of the performance appraisal is as long as customers are involved in designing and administering it. Likewise, the content of training pales in importance beside the response if customers are doing the teaching or are in the room when training occurs. Many HR professionals are finding creative ways to include customers in HR practices.

Customer Involvement and Staffing

An airline attempting to make flying more fun screens flight attendant résumés, then invites job finalists to audition interviewees in front of a panel of frequent fliers. A restaurant selecting a chef invites target customers to taste the selections of the finalists and to offer their vote on which chef they would prefer. A hospital invites physicians, third-party payers, and investors to interview potential administrators.

Customer participation in staffing can increase the quality of decision making. Observing teachers teach and soliciting data from students in the class helps boost the quality of teachers hired. Asking customers to define competencies of first-line supervisors creates a dialogue about what matters most to customers and how that translates to internal managerial behaviors. In addition, customer participation in staffing tends to increase customer commitment to the person hired as well as to the business.

Of course, hiring is traditionally the most closely held of organizational prerogatives, and many executives—inside and outside HR—may worry about letting the fox guard the henhouse. However, it isn’t necessary to let go entirely—giving customers a voice is enough. They don’t need or want the only voice.

Customer involvement can include sharing talent. For example, a utility firm that wanted marketing experience for one of its executives arranged a three-month exchange with a major customer, who was equally interested in quality control experience for a similar rising talent. The two participants learned more than concepts as they worked on projects for their loaner management; they also forged relationships across boundaries.

Customer Involvement in Training and Development

GE’s Crotonville training center opens many of its programs to customers, particularly in emerging markets. By including key customers and thus educating the value chain in its language, management philosophy, and decision processes, GE finds it can shape how customers think and act—thereby redefining the rules of engagement and succeeding quickly in new markets.

Few companies take full advantage of the opportunities their own training programs offer. Most internal courses draw students only from within the company, even though the payback may be often huge and the incremental costs of adding a few outside participants are diminishingly small. Consider the advantages of identifying customers who would be well served by the content of a course, inviting them to attend, and building relationships with them during the program. One company now requires 10 percent of the seats in all its courses to be open to customers and encourages sales and marketing to promote the benefits of course attendance as part of the sales package—a special offer that valued customers welcome.

It can also be valuable to offer programs designed primarily for customers. In one case, a firm that repaired railroad cars cut its in-process time from twenty days to ten, but rather than reacting with the expected delight, customers yawned. The repair people met with customers to explore this disappointment, and learned that they’d barely dented the total downtime, because the cars were also out of commission about ten days on either side of the repair itself. They held a customer productivity workshop, sharing the technology and processes they’d used internally. By focusing on the total time a car was unavailable, they were able to reduce the original forty days to about fifteen.

Another useful move is to enlist customers as presenters—and not just on technical topics. Customers are often willing to share candid observations about why they do or do not purchase. For example, an electronics company invited three customers who had recently gone with a competitor to attend an officer meeting and talk about their decision processes. Collectively, these three lost customers represented a major account erosion, and officers at the seminar not only listened but committed to act upon what they learned. The customers were, at the very least, disposed to see if management succeeded, and the insights the company gained helped reduce further erosion.

Customer Involvement in Appraisal and Rewards

Customers in the appraisal process? Some companies are giving customers a voice in allocating rewards based on quality of employee service. This yields a double benefit: customers grow more committed to employees, and employees to customers.

For example, one airline sends its best customers this annual letter: “We know you are one of our most frequent fliers. We are committed to excellent customer service. Because you travel our airline so often, we assume you know how to define customer service. Enclosed with this letter are ten coupons, each worth $50. When you experience exceptional service from an airline employee, ask for the employee’s name, sign the coupon, send it to the company, and we will pay the employee $50.” This program uses part of the regular bonus pool to create a clear line of sight between customers and employees.

Customer Involvement in Governance and Communication

The task forces most organizations use to design and deliver systems and services usually consist only of employees—and even gathering members from multiple functions often seems like a stretch. But as the railroad car repair company found, enlarging the task force to include more of the supply chain invariably improves its results.

And task forces are only the beginning. Both public communications (i.e., newsletters, videos, and the like) and personal contact can help transfer knowledge. The benefits can be emotional, as when Medtronic invites recipients of its implants to talk to employees about what the company’s product means to their lives. Or the benefits can be directly tied to day-to-day production, as when Wal-Mart connects its electronic system to its supplier network to provide immediate information about what is selling and what is not selling so suppliers can adjust their production accordingly.

Customer Summary

What employees do inside the organization affects customers outside the organization. When HR professionals define target customers, make the customer value proposition explicit, align HR practices to customer values, and involve customers, they create customer experiences that build loyalty and add value.

The Value Proposition as Defined by Investors and Customers

Remember Dan Bennett and the innovative HR program that opened this chapter? Despite its smooth implementation, the program couldn’t be counted a success based on the information we provided. But now we can add that Dan’s task force designed and delivered the program not only with customers in mind but also with customers fully involved. They carefully linked it to organization capabilities that built intangibles important to investors and also supported a customer value proposition. This is not a “false positive.” It’s a genuine success. HR professionals can and should blur boundaries by integrating what happens in the organization with what customers and investors experience outside it.