2

External Business Realities

HR PROFESSIONALS and their stakeholders have too frequently operated in separate worlds. However, to create value, you have to know what value is—and value is defined more by the receiver than the giver. That means HR professionals must learn to help their stakeholders address the issues that matter most to them. They must, therefore, understand the fundamental external business realities that shape industries and companies. The realities that influence business may be grouped under three headings:

- Technology

- Economic and regulatory issues

- Workforce demographics

A fourth factor, globalization, cuts across and influences the other three.

To maintain their credibility, HR professionals must know the trends in each of these areas, the facts behind the trends, and where these facts may be accessed. Assembling this pool of information requires constant awareness of the world. Knowledge of external realities isn’t something to be accomplished once and ticked off on a to-do list. Instead, it’s essential to ask—and keep asking—four questions: What are the important trends for each of these realities? What are the key data points that illustrate these trends? What do I need to know about these trends in order to contribute to management team discussions? Where can I find this information?

In this chapter, we synthesize the key trends in each area with a brief sample of the logic and supporting data and information on how to access the data. We also provide a self-test that you can use to assess your knowledge. Our experience is that HR professionals must understand the basic trends. To have credibility at the strategy table, you must also be able to support your statements with empirical data about business trends, lest you be seen as ill prepared or superficial. This chapter does not attempt to review all categories of external business realities, but it does give a broad indication of the kind of information that HR professionals will increasingly be expected to master as management team members.

Technology

Technology—the application of knowledge to the transformation of things into other things—drives almost every aspect of the changing business environment. As applied to organizational processes, technology may be used to automate transactions in HR, finance, sales, legal, operations, and purchasing. Technology enhances engineering and design processes, and moves goods efficiently and accurately through the manufacturing process. It can also be applied to the design of new products or services.

HR professionals cannot ignore technology either in their own operations or in those that affect the organizations they serve. Depending on the industry in which they work, they must be able to understand how people create new technologies that keep their firms ahead of the competition. They may also need to understand how to apply existing technology to new applications.

They need to help their organizations and people adapt to the pace of transformation spawned by emerging technologies. They need to understand and create cooperative and synergistic cultures in which people can freely and accurately communicate across departmental and national boundaries. They also need to know how to create and sustain the new forms of organization—flatter, virtual, and horizontal—that are made possible and mandated by emerging information, process, and product technologies.

The major trends in technology fall into four dimensions:

- Speed. Things are moving faster and faster. “Moore’s Law,” the 1965 projection that microprocessor speed would double roughly every eighteen months, has held true to this day. In the last forty years, the speed of microprocessors has increased 4.5 million percent. Prototypes exist to maintain Moore’s Law through 2011.1 In many ways, the whole world seems to be following suit.

- Efficiency. Per-unit costs are dropping as speed increases. For example, in chip manufacturing, the cost per transistor unit has dropped from a dollar to a millionth of a cent in the past thirty years.2 By continually applying technology to enable business process improvement, Dell has created impressive manufacturing results. Its manufacturing workstations are 400 percent more productive than industry standards. In its new facilities, production output is up 40 percent as it produces a customized computer every four seconds.

- Connectivity. Up and down the supply chain, stakeholders are being tied more and more closely together as technology brings “Reed’s Law” to life.3 Reed’s Law suggests that the number of possible connections in a network rises exponentially compared to the number of nodes. The world is rapidly reaching a point where every human being can be a node in a network that includes every other. Large and powerful human networks are created through technology on a massive scale in unforeseen and radical ways.

- Customization. Technology allows companies to identify customer requirements more quickly and more accurately and to translate requirements into customized products and services. BMW customers electronically feed their new-car specifications directly to thousands of suppliers and factories. Based on supplier parts availability, distribution information, and Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM) production schedules, the delivery date of the customized vehicle is calculated and communicated to the customer in five seconds. Eighty percent of BMW sales in Europe are now customized in this manner.

All these changes will have an impact on the work of HR over the next few years; any of them will likely have an impact on your work tomorrow. It’s that close. Since any of these changes could be—and many already are—the subject of whole books, we will explore just one major trend here.

Smart Mobs

The spiraling growth in connectivity has profound implications for organizations and for HR. Technology enables “people to act together in new ways in situations where collective action was not possible before.” 4 New blocks of customers, suppliers, employees, and owners can form overnight. Called smart mobs, these groups can mobilize themselves to undercut pricing, raise product and service standards, communicate satisfaction or dissatisfaction, and impose substantial pressures on their target organizations. Examples range from the company-sponsored to the upstart. People with major complaints about products and services, companies, and politicians create Web sites that allow them to access large-scale audiences, thereby mobilizing collective action that otherwise would not have been possible. Based on their personal interests, people then vote with their time and energy for the espoused cause. For example, SaveDisney.com was established by dissident shareholders to voice their dissatisfaction with the Disney executive leadership in hopes of ousting that leadership and reorienting the strategic direction of the company and its values. EBay has turned into one of the great success stories of the Internet, with a transaction volume larger than half of the world’s economies.5 More cars are sold on eBay than in the largest dealership in North America. At the same time, among its 12 million daily listings are toothbrushes and dental floss. It is estimated that more than one hundred fifty thousand cyber-entrepreneurs earn their full-time living selling merchandise through eBay. What makes eBay work? At its heart, eBay facilitates a forum for the swarming of groups around specific personal interests that have economic value. Buyers and sellers conduct transactions and regulate cheaters on a global scale without face-to-face interaction. EBay provides the technological context for the nearly instantaneous creation and execution of frictionless markets within a self-regulating global democracy.

But technology-enabled connectivity has a dark side as well: online gambling and pornography can expand unabated without the social moorings of family and community restraint. International terrorists, pedophiles, and emerging slave traders find one another online. To counter these unsavory forces, legal and commercial online surveillance mechanisms are being developed that may compromise individual privacy. Grappling with the dark side of technology has obvious strategic and policy implications for organizations and their HR departments.

Globalization and Technology

Globalization occurs when goods and services, capital, information, and people move across national borders. Such movement is intensified and accelerated by technology. For example, global trade has been substantially enabled in recent years through massive reductions in transportation, freight, and communications costs. During the last half of the twentieth century, air transportation costs dropped by about 60 percent, sea freight costs by 20 percent, and both digitized voice and data communications by more than 99 percent.6

Meanwhile, through more sophisticated job design, companies are able to split up the value chain and allocate work on a global scale to locations anywhere in the world where work can be done at the highest quality-to-cost ratio. This trend is a key feature of contemporary trade. It occurs under a variety of different vernaculars, including outsourcing, vertical trade, multinationalization of production, slicing up the value chain, and disintegration of production. Eli Lilly allows hobbyists to swarm over its most difficult technical issues. At Lilly’s InnoCentive.com Web site, the company describes thorny problems in some detail. Anyone with an Internet connection anywhere in the world can read about a problem, take it to a garage workshop or basement hobby room, develop a solution, and submit it back to Lilly—receiving a financial reward for success ranging from $5,000 to $100,000. Through this means, Lilly is able to access intellectual capital that was heretofore not only inaccessible but unknown.

The globalization of information likewise is occurring on an unprecedented scale. Information is instantaneously available around the world. Furthermore, repeat visits to Web sites create a market for accuracy and credibility—and can at the same time also reinforce misperceptions and feed fanaticism on a global scale.

What HR Professionals Need to Know About Technology

To contribute to management team discussions about technology, HR professionals need a knowledge base about the current technological possibilities and a general vision about the future role that technology might play in their firms. With this knowledge, they will be able to add value to strategic discussions that involve technology, understand the dynamics that influence their key constituents, and align strategies and practices to these constituents’ needs in a timely and accurate manner.

ASSESSMENT 2 - 1

Knowledge of technology

The questions in assessment 2-1, Knowledge of technology, can help HR professionals determine what they already know and what they might need to know about technology.

Resources Regarding Technological Trends

A major purpose of this chapter is not only to review current trends and data relative to technology, economy, and demographics but also to provide an overview of sources to which you may turn in order to stay current in these topics over time. Many magazines, newspapers, and journals are dedicated to presenting, analyzing, and projecting trends in current and emerging technologies. The basic business magazines regularly review technological trends: Business 2.0, Business Today, BusinessWeek , the Economist, Far Eastern Economic Review, Fast Company, Forbes, and Fortune. The major business newspapers in Europe and the United States likewise carry informative articles: Financial Times, Handelsblatt, and the Wall Street Journal. For greater detail, several magazines and journals specialize in various aspects of technology: Invention & Technology , Technology Review, Scientific American, Science, American Scientist, the New Atlantis, International Journal of Technology Management, Technology and Culture, TechComm, the Journal of Technology Transfer, and Journal of Information Technology. Several online sources are also useful for staying current with economic trends: CNN.com, MSN.com, News.BBC.co.uk , FoxNews.com, MagPortal.com, SciTechResources.gov, InfoTech-Trends.com, CDT.org, and www.Publications.parliament.uk. You might access this information by selecting key information sources and regularly following them, by assigning someone to synthesize key technology advances and share this with you and others, or by inviting technology experts to periodically update HR professionals.

Economic and Regulatory Issues

Economic and regulatory environments provide the context for business operations. They are frequently the precursors to changes in the expectations of customers, shareholders, managers, and employees. If HR professionals are to contribute to business decisions, they must know where to go to learn the basic trends in these areas. They must have data about these factors; and they must be able to use this knowledge in providing intellectual richness to strategic business discussions.

Economic Factors

Even in the context of an economic downturn of the early years of the twenty-first century, the overall U.S. economy has been growing at a healthy pace. However, many economists project that the world economy will continue to grow but will become more volatile in coming years, with periods of rapid improvement followed by periods of rapid decline. Several trends predict prospects for sustainable global economic growth:

- Workforce quality. The collective knowledge and skill level of workers continues to increase on a global scale. The population of highly skilled workers in countries such as China and India is high and rising.

- Workforce flexibility. The flexibility of the U.S. workforce is one of the primary strengths of the U.S. economy, especially when compared to the relative workforce immobility of Japan, Germany, France, and Italy. The movement of people from one industrial sector to another encourages growth where growth is possible and greater productivity where demand is diminishing. While workforce flexibility creates substantial turmoil and pain in the lives of many, the long-term total economic benefits are clear.

- Investment. Although investments in new products, services, technologies, processes, and equipment may be erratic in specific industry sectors, the overall trend is toward continued and substantive investment. Likewise, investment in merger and acquisition (M&A) activity is anticipated to continue in upwardly spiraling waves that roughly track upward fluctuations in stock price.

- Health. The world is generally becoming a healthier place. However, the cost of maintaining human health is an issue of concern for the countries as a whole as well as for individual companies. U.S. HR professionals face three challenges: keeping the workforce healthy at a low cost, reducing the total costs of health care insurance, and contributing to the national debate on health care.

- Increasing wage disparity. Over the past three decades, the number of people with poverty-level incomes has continued to sharply decline. However, real wages for the top income brackets continue to sharply increase at 1.5 percent per year. Meanwhile, average real wages of those in the lower bracket continue to decline.7

- Productivity improvement and long-term economic optimism. Most developing countries are experiencing strong growth in labor productivity, with the United States surging ahead at a remarkable 2.8 percent annual increase.8 This improvement matches the post–World War II productivity surge of 1948 to 1973 and is almost double the productivity figure of 1.4 percent from 1973 to 1995. The implications of such statistics are dramatic. At an annual productivity increase of 1.4 percent, real national income doubles in fifty years. At an annual productivity increase of 2.4 percent, real national income doubles in approximately twenty-six years. The implications for the economic well-being of a country are obvious; productivity is a major driver of the economic growth.

Workforce Productivity

The importance of productivity as driver of economic well-being warrants some additional discussion. Productivity per worker continues to improve across many segments of the economy. In recent years, productivity in the U.S. manufacturing sector has increased at twice the rate of the overall nonfarm economy. As a result, gains in manufacturing productivity now contribute more to gross domestic product (GDP) growth than the gains of software and retail combined.9

The U.S. steel industry serves as an example. During the last two decades, production in the U.S. steel industry increased 35 percent. At the same time, the number of workers in the steel industry decreased 76 percent. Those workers who remain earn on average from $18 to $21 per hour.10

While manufacturing jobs decline, the number of jobs that require analysis and intellectual judgment—such as systems designers, product engineers, financial analysts, and marketing specialists—is growing. In the service sector, jobs are also on the rise in both the low- and high-end pay categories. Relatively low-paying McJobs at fast-food restaurants, hotels, and convenience stores are increasing, as are service jobs that pay well, such as nursing, computer consulting, and after-sales service.

Some people believe that technology-driven productivity is an enemy. They reason as follows: technology increases labor productivity. This means, by definition, that fewer people produce each unit of output. This causes unemployment, which reduces consumer spending, which in turn reduces demand. Thus, the economy should go into decline. This logic makes sense, especially in the short run and in times of recession. Over the long run, however, empirical evidence simply does not support it.

Over the past fifty years, real wages grew fastest and unemployment was at its lowest during periods of greatest productivity. As productivity gains spread broadly over the economy, the result is higher income per person, cheaper products, and greater competitiveness for the companies that produce them. These outcomes increase demand for products and services, and increased demand produces new jobs. This is sometimes referred to as the “virtuous cycle of productivity.” The good news is that this cycle is anticipated to continue for at least much of the decade. And the cycle will be experienced not only by high-tech firms such as Intel and Dell but also by low-tech firms such as Wal-Mart as they apply technology to their operations.

A Big Question

Totaling $44 trillion, the U.S. federal deficit is at an all-time high by a substantial margin. 11 And the intensity of the problem appears on the upswing, as the impending retirement of baby boomers places additional burdens on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. The diversion of resources from corporate investments toward paying the deficit is likely to make the United States less and less attractive to foreign capital. The implications of this challenge have yet to be defined, but we are safe in assuming that the business implications will be nontrivial.

Globalization and Economics

Global trade now approximates more than a quarter of total Gross Domestic Product (GDP).12 Since the years immediately following World War II, imports have risen from $60 billion to $6.5 trillion, and exports from $58 billion to $6.3 trillion. Over the past two decades, global merchandise trade expanded 300 percent to a total of $6.4 trillion. Trade in services increased by 400 percent to a total of $1.5 trillion. The service sector represents a small proportion of the total, but it is growing more quickly than the merchandise sector. Both are growing at a much faster rate than the globally aggregated domestic GDPs. While more pronounced in high-income countries, trade growth is also increasing in middle- and low-income countries at 19 percent and 8 percent, respectively. Furthermore, these trends are likely to continue. For example, it is estimated that the annual U.S. trade rate will increase by approximately 7.9 percent.13

As might be expected, the flow of capital across international borders correlates closely with the flow of goods and services. Capital flow across borders occurs in two different ways.14

First, nondomestic companies invest in operations in other countries or purchase equity in other countries. This is referred to as foreign direct investment, or FDI. Such FDI is an important element of the U.S. economy. In recent years, non-U.S. firms operating in the United States accounted for 16 percent of the employment and 18 percent of the sales in the U.S. manufacturing sector, and they tended to pay salaries at parity with their domestic counterparts.

Second, nondomestic companies invest in the purchase of bonds, equity, and other financial instruments. For example, non-U.S. firms or individuals may seek to maximize their long-term returns by investing in relatively stable but low-return U.S. financial instruments, or they may invest in the relatively unstable but potentially high-return China markets. In this way, global capital flow can be healthy for both the investor and the investee. In a potentially unsettling trend, however, countries are beginning to acquire so much capital that they could potentially influence the foreign policy of the debtor countries. Such debt disequilibriums are beginning to occur as China and Japan control a substantially disproportionate percentage of the U.S. debt.

However, globalization will continue to be limited by local political and social dynamics. Many countries experience both positive and negative effects on national sovereignty from international governing bodies such as the World Trade Organization and the United Nations. Regional trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) have proliferated and are hotly debated for both their positive and negative outcomes. In many countries, free access to nontraditional information and social norms interrupts and threatens traditional sources of information and norms such as religion and family. Knowledge and special interest bonds through the Internet, the media, or direct contact frequently increase conflicts with family relationships and ethnic ties. These dynamics may place pressures on the free flow of trade. However, individuals, communities, industries, and companies that are prone to limited foreign trade and allow protectionist trade barriers will do well to remember that national regulatory protectionism was a major contributor to the intensity of the global financial crash of 1929.

Globalization will continue to diminish the influence of organized labor. Four factors contribute to the decline of unions in an everincreasing global business environment:15

- The large multinational corporations that drive much of economic globalization have jobs and work that tend to be geographically mobile.

- Global population growth in low-income countries provides greater labor supply on a global scale while at the same time technology-driven productivity improvements have reduced labor demand in high-income countries.

- Especially in developed countries, there has been a shift away from the relatively more organized manufacturing sector to the less organized service sector.

- Most low-income countries that are moving onto the global playing field tend to have weak traditions of unionized workforces.

In the short run, there are clearly winners and losers in the dynamics of global trade, among individuals, job categories, industry sectors, and countries. Developed countries are currently experiencing a loss of jobs to countries that are able to process digital information or transact administrative tasks at equal or higher skill levels and at lower cost. However, other sectors benefit from job creation that occurs through foreign trade (for example, the U.S. agriculture and entertainment industries). The net good news is the general consensus among economists that the world is generally better off with global trade than without it.

Regulatory Factors

Ask any group of line or HR managers if they believe the world is becoming more or less regulated, and the response will probably be that the world is becoming more regulated. It certainly feels that way—especially in light of legislation about the environment, discrimination, harassment, privacy, board composition, whistle blowing, and so on and on.

Yet the last two decades have seen deregulation on a scale unprecedented in human history. HR professionals need to bear in mind that since the mid- to late-1980s, trillions of dollars of economic activity has been deregulated. This deregulation has been most intense in the easing of trade restrictions with the former U.S.S.R, China, and India as well as deregulations in many domestic industries (such as utilities, interstate banking, and transportation). Deregulation has also contributed to a substantial reduction of tariffs that has enabled the steady and profound increase in global trade.16 Throughout this century, tariffs have been erratic in the short run, but steadily declining in the long run. This trend is expected to continue.

HR professionals must understand this massive worldwide trend toward deregulation and the implications of this trend in order to add value at the strategy table. Otherwise, they may be tempted to overemphasize regulatory matters.

HR departments have traditionally been among the most regulated; they are heavily involved in dozens of major legal issues that must be addressed if the company is to focus on issues more germane to its competitiveness. Despite unprecedented deregulation, important regulatory forces are still active. HR professionals, as contributing members of the strategy team, must be aware of these forces—the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, for example, as well as efforts to rein in the mutual fund industry to ensure ethical practices. In addition to these large-scale business-focused regulatory matters, HR professionals will continue to remain the caretakers of more traditional HR-related legal issues:

- Legal requirements for collective bargaining. How do you optimally work with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)? How do you make your case to the union leadership and to union members? How do you effectively work within the provisions of the labor contract?

- Legal rights of individuals to work free from discrimination based on gender, race, color, religion, sexual orientation, ethnicity, age, or disability.

- Legal protections that allow people to work in a safe environment, free from physical threat or forms of psychological harassment.

- Legal rights of employees relative to testing, evaluation, discipline, compensation, severance, and privacy.

- The implication of legislation concerning maternity and paternity leave, medical care, insurance, and white-collar collective bargaining.

In recent years, the highest-profile discussions in the area of regulation affecting HR and companies in general have revolved around the question of ethics. The Enron debacle became a lighting rod for society’s discomfort with conflict of interest, misuse of positional influence, greed without constraint, and complex financial deception. Public demand for reform intensified with revelations of malfeasance from WorldCom, Global Crossing Ltd., Tyco International Ltd., and Arthur Andersen. The involvement of HR professionals relative to ethical issues is substantially increasing. For example, almost every provision of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act has implications for HR professionals and the discussions they may have with their counterparts in other departments.

What HR Professionals Need to Know About Economic and Regulatory Issues

To contribute to management team discussions about economic and regulatory issues, HR professionals need to be aware of the basic trends relative to these issues and know where to find them. However, they also need to be able to back up generalizations about basic trends with specific data. With this knowledge, they may then

- Add value to strategic discussions about economic and regulatory issues.

- Understand the economic and regulatory dynamics that influence their respective firms directly as well as those that influence their firms indirectly through customers, shareholders, managers, and employees.

- Align their HR strategies and practices to HR’s key constituents in a timely and accurate manner.

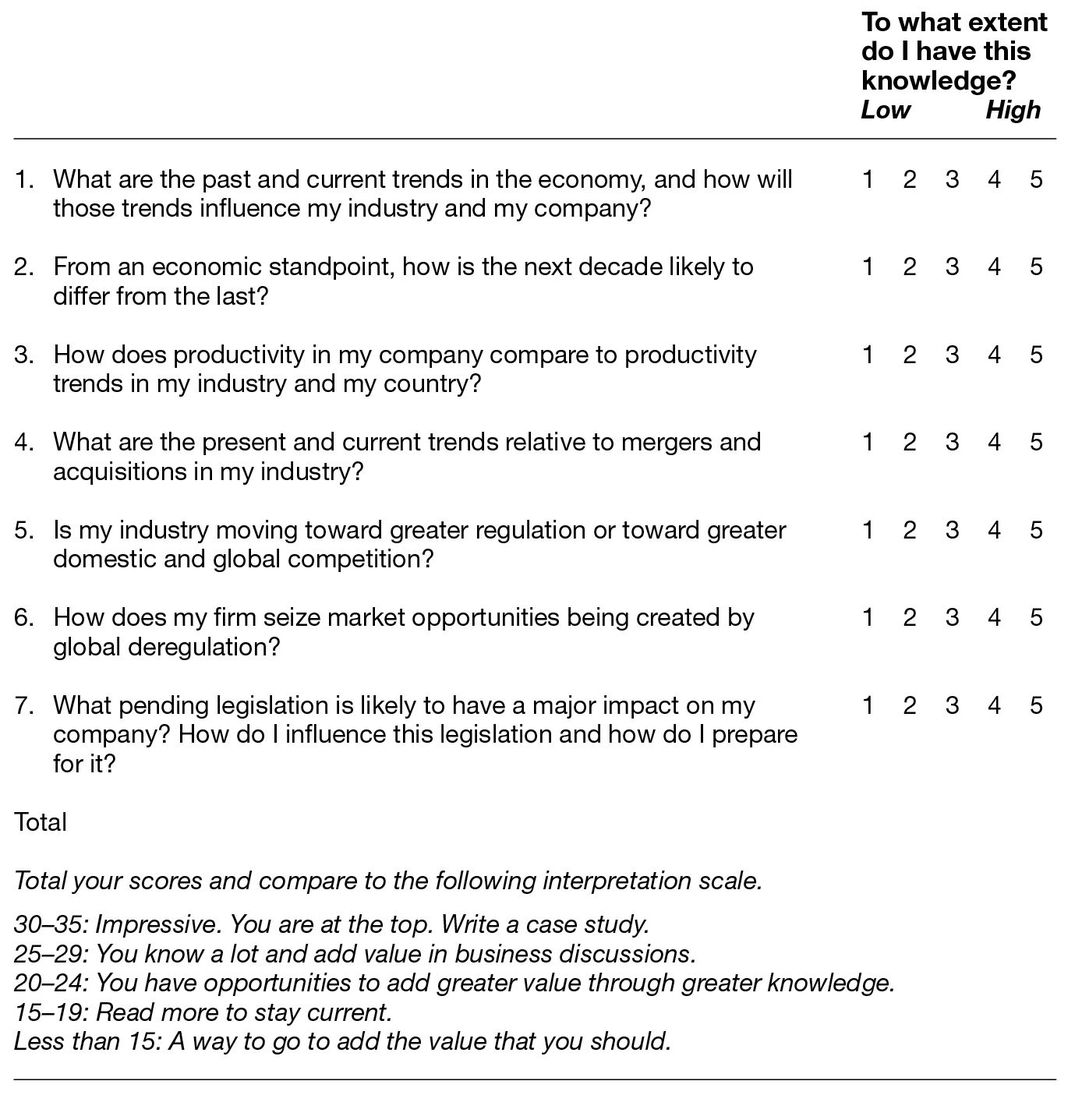

The self-assessment in assessment 2-2 gives HR professionals an idea of what they already know about economic and regulatory issues and what they might need to know for the future.

Resources Regarding Economic and Regulatory Trends

Potential sources for information about economic and regulatory trends are plentiful and easily accessible. The major business magazines and newspapers provide reasonable, and usually credible, summaries of economic and regulatory matters that have implications for business organizations: Business Today, BusinessWeek, Dun’s, the Economist, Far Eastern Economic Review, Forbes, Fortune, Inc., Financial Times, Handelsblatt , Investor’s Business Daily, and the Wall Street Journal. Many publications are available that specialize in economics and regulatory matters and are generally user-friendly: the Columbia Journal of World Business, Comparative Strategy, Economic Policy, Economic Policy Review, Encyclopedia of American Industries, the EU Economy Review, Foreign Policy, Handbook of North American Industry, Harvard Business Review, the Journal of Comparative Economics, Journal of Economic Literature, Journal of Economic Perspectives , Journal of Public Policy, Journal of World Trade, Standard & Poor’s Industry Surveys, US Industry & Trade Outlook, the World Bank Economic Review, the World Bank Research Observer, and the World Economy. Web sites that contain useful information about economic and regulatory issues include Business.com, bized.ac.uk, IndustryLink.com, www.Census.gov, Europa.eu.int, Ita.doc.gov, and Stu.findlaw.com.

ASSESSMENT 2 - 2

Knowledge of economic and regulatory issues

Workforce Demographics

Workforce demographics that influence the pool of labor available to conceive, develop, produce, distribute, and sell products and services are changing in turbulent ways. Demographics likewise directly influence the demand for types and volumes of products and services. HR professionals need a grasp of basic global and domestic demographic trends—and, at the strategy table, they also need to have specific data to back up their assertions regarding these trends.

Five categories of demographic trends—declining workforce growth, increasing age of the workforce, changing gender balance, increasing ethnic diversity, and deteriorating family economic health—are most relevant for business discussions.

Declining Workforce Growth

Over the last twenty years, labor-force growth rates have been declining, and this decline is expected to continue for the next twenty years, into the 2020s.17 This trend will have a substantial impact on the demand for goods and services as well as on the ability of society to supply those goods and services, and it will eventually put the brakes on economic growth.

Increasing Age of the Workforce

Over the next two decades, the U.S. population aged 55 and older will increase 73 percent, while the number of younger workers will grow by only 5 percent. As a result, the proportion of working-age people to retired people will be about half what it was in 1950. The resulting stress on social systems will be partially counterbalanced by a tendency for people to stay active in the workforce into their later years—partly in response to economic necessity, partly as a result of the more widespread health and vigor in older folks that are permitted by medical developments.

There is substantial economic need for people to stay active in the workforce: (1) to support the health and welfare programs they will require as they age, (2) to continue their contributions to national productivity, and (3) to drive demand for consumables. Because of the economic mandate for older people to work more in their later years than they have in the past, a number of provisions have been implemented to encourage them to remain active in the workforce, such as raising the retirement age for full Social Security benefits from 65 to 70. The general shift from defined benefit pension plans to defined contribution plans also reduces the incentives for early retirement. During the last decade, 90 percent of defined benefit plans specified that employees retire at 62 or earlier. 18 That percentage is beginning to decrease.

In addition to overall economic requirements and financial incentives, other factors are enabling older people to remain active workforce participants. As we move into the twenty-first century, older individuals are physically and psychologically healthier than they were a few years ago. The percentage of people over 65 with one or more chronic disabilities declined 5 percent over the past twenty years or so.19 Meanwhile, employers are recognizing the desirability of older workers, who tend to be more flexible than workers with young families in terms of work schedules and work requirements. They represent an enormous volume of proven knowledge and skills, and can serve as effective developers and mentors of future talent as they transfer their skills to the next generation.

As a result of these inducements and incentives, we can expect an increase in workforce participation among the elderly. During the next decade, the percentage of individuals 65 to 74 years old that are active in the workforce is projected to increase from 14.8 percent to 17.3 percent.20

However, older workers also present a unique set of challenges to their employers. Older workers tend not to be as technologically current as their younger counterparts. They may be less flexible in their thought and behavior patterns. And they tend to be relatively more expensive. To address these obstacles, companies will need to make investments in updating the general as well as technical skills of older workers. They will also need to think through alternative job-sharing and job-transfer policies that will provide on-the-job skill development.

Many developed countries besides the United States are aging at a considerably faster rate due to the double impact of increased longevity and reduced birth rates. In Europe, for example, the overall birth rate has declined more than 50 percent to a low of 1.4 children per person. This results in a dramatic shift in the ratio of elderly to working-age adults. During the next fifty years, the ratio will more than double (from 21.7 to 51.4). In Japan, the ratio will almost triple (from 25.2 to 71.3). This translates into only 1.4 working adults for every elderly person. The number of elderly people per 100 working-age adults in developing countries will increase dramatically. In China the ratio will almost quadruple, from a relatively low 10 to a high of more than 37 older people for every 100 workers.

Europe is now beginning to take steps to encourage older workers to remain active in the workforce. These steps are politically unpopular, but they are occurring nonetheless. In 2003, Austria raised its retirement age for men from 61.5 to 65 years and for women from 56.5 to 60 years. In Germany, the effective retirement age has increased from 63 to 65 years.

Changing Gender Balance

Since 1950, men’s workforce participation rates have declined steadily, while women’s rates have increased. The decline is especially notable for older men. In 1948, 90 percent of men aged 55 to 65 were working. 21 By the turn of the century, the proportion of working males in this age group had declined to 67 percent. Meanwhile, during this same time period, women from age 16 to 64 increased their workforce participation from 34 percent to 60 percent.

As women make up a greater proportion of the total workforce, their influence at all organizational levels is being felt. In 1995, 8.7 percent of Fortune 500 corporate officers were women. Currently, that number has risen approximately 64 percent. The U.S. Labor Department has reported that women hold 45 percent of managerial positions.22 Yet women occupy only 5 percent of the CEO positions in U.S. public companies with net sales over $5 billion. This has at least four possible explanations. First, it may be that male-dominated boards continue to harbor the unverified view that women are unable to handle the intellectual and emotional demands of the top jobs. Second, the top jobs in most companies place extraordinary demands on the time and psychological reserves of their incumbents. It may be that women are more evenly balanced in their approaches to work, life, and family. For example, in business positions, females tend to work shorter work hours than males.23 (It has been argued that this indicates that women require fewer hours per week to complete their work. Other explanations are also possible.) Third, women are disproportionately represented in staff positions such as HR, finance, and marketing. These positions do not provide the general management experiences necessary for senior line positions. Fourth, men may be more overtly aggressive in business settings. For example, Linda Babcock of Carnegie Mellon University found that male graduates with a master’s degree earn 7.6 percent more than their female counterparts. Most of this difference can be attributed to the fact that only 7 percent of the women negotiated for pay greater than the initial offer, whereas 57 percent of the men did so.24

If performance in academic and extracurricular leadership experiences is indicative of future success, then women are likely to continue to achieve and prosper in senior management jobs. Women achieve 33 percent more bachelor’s degrees than men, and 38 percent more master’s degrees.25 These numbers are expected to increase for at least the next decade. In both primary and secondary schools, girls tend to receive higher grades. Boys tend to score better on the SAT. However, much of the difference in SAT scores is accounted for by the fact that 10 percent fewer boys take the SAT, and those 10 percent tend to be boys who would have had lower scores on the SAT.26 Currently, slightly more girls than boys are enrolling in high-level math and science courses. More boys are suspended from school. Seventy-three percent of children diagnosed with learning disabilities are male, and boys are 400 percent more likely to be on Ritalin or similar drugs.

The irony of these statistics is that the fear that prevailed in the mid-1990s—that girls were falling behind in academic achievement—turns out to be questionable. During those years, public school researchers, administrators, and teachers allocated considerable money, time, and attention to elevating girls to greater scholastic success. The data may indicate the need to allocate similar resources to help the boys. It is not a win-lose situation. Both boys and girls are the foundation of the economic future.

Increasing Ethnic Diversity

Whites will continue through the first half of the twenty-first century to be the largest segment of the U.S. population. However, that situation will change dramatically toward the middle of the century. By the year 2020, their numbers will have fallen to 63.3 percent, and by 2050 to 50.1 percent.27 Hispanics will almost triple their proportion, from 6.4 percent of the population to 17 percent, as will Asia/Pacific Islanders (from 1.6 percent to 5.7 percent). The Asian population in the United States will more than double, to a total of 33 million. The African American population will pick up one percentage point, from 12 percent to 13 percent. Native Americans, who form the smallest segment of the population, will grow from 0.6 percent in 1980 to 0.8 percent in 2020.

It is clear that the social and economic influence of Hispanics will increase significantly.28 Hispanics now make up 12 percent of the U.S. workforce. In two generations, that 12 percent will more than double to 25 percent. The family income for Hispanics averages around $33,000. This is well below the U.S. average of $42,000. However, over the past decade, Hispanic disposable income in the United States has increased approximately 46 percent. This rate of increase is double the pace of the rest of the U.S. population.

Deteriorating Family Economic Health

During the second half of the twentieth century, households inhabited by married couples slipped from 80 percent to 50.7 percent.29 Thus, unmarried or single households are on the verge of defining the new majority. The traditional family structure is not only under social pressure; it is under economic pressure as well.30 In the last quarter of the twentieth century, family bankruptcies increased 400 percent. Much of this was due to the loss of the cushion provided by normally unemployed mothers and wives, who could often find at least some income if the main breadwinner became unemployed. With mothers working full-time, the traditional economic buffer of middle-income families is now gone.

The Influence of Globalization

The world’s labor forces are becoming more global in two ways.

Through Migration of People, Countries Are Becoming More Global

As people migrate across national boundaries, the demographic makeup of countries becomes more global. Cross-border movement of labor tends to be from south to north, from poor to wealthy, and from less stable to more stable. In recent years, 175 million people, or 3 percent of the global population, lived in countries different from the ones where they were born. One out of ten people in developed countries and one out of seventy people in developing countries are immigrants. And the percentages are increasing.

Through the Migration of Work, Companies Are Becoming More Global

The dominant globalization of labor is not through the migration of people but through the migration of work from one country to another, either from the organizing of work on a global scale or from the outsourcing of work to nondomestic locations. Organizing in-house work on a global scale allows companies to increase their speed, quality, and efficiency and to implement 24/7 work processes. Work that is started in the United States is passed to Europe, on to Asia, and then back again—sequentially and continually. Companies are also increasingly moving work to offshore subcontractors, wholly owned foreign subsidiaries, or large-scale offshore suppliers. This has become one of the dominant trends in business in the first decade of the twenty-first century. However, it is useful to remember that there have been at least four waves of labor offshoring since World War II:

- 1960–1975. Exodus of low-skill jobs such as the production of toys, inexpensive electronics, and leather goods

- 1975–1990. Exodus of simple service work such as the writing of software and the processing of credit card receipts

- 1990–2000. Movement of knowledge work to anywhere on earth where people are intellectually capable and where cost advantage exists

- 1995–today. Movement of any work that can be digitized to any countries that have skill, knowledge, and an Internet connection

Industrialized countries have adjusted their labor markets to be consistent with these trends in the past. The adjustments have not been without substantial pain for those who had to move their jobs or change their careers, but over time the industrialized nations have been economically better off for having done so. Nations that have resisted such labor market flexibility have not thrived.

Estimating the numbers of outsourced jobs requires a bit of guesswork. Most informed estimates are that 100,000 U.S. service jobs went offshore in 2000. That number will increase to 1.6 million by 2012, and to 3.3 million by 2015.31 Jobs to be outsourced run the full gamut of service vocations, including financial analysis, office and technical support, sales, middle management, architecture, legal services, art and design, life sciences, and general business. Especially hard hit will be IT jobs such as software development, reengineering, maintenance, documentation, telephone support, remote network monitoring, systems management, and administration and operations.

Currently, 5 percent of U.S. firms with sales above $100 million were engaged in offshoring or had immediate plans for doing so. That number is expected to grow dramatically. Some examples:

- Fluor Corporation employs 1,200 engineers and draftsmen in the Philippines to turn layouts of large-scale industrial facilities into detailed specs and blueprints.

- Procter & Gamble (P&G) employs 650 people in Manila to assist in the processing of its tax returns from around the world.

- Bank of America has moved 3,700 of its 25,000 technical support and head office jobs to India, where the wages are $20/hour instead of the $100/hour they would cost in the United States.

Educational Advantage

Productivity and innovation are critical sources of comparative advantage for U.S. companies, and both are directly linked to the educational level of its workforce. A 10 percent increase in the average education of workers is associated with an 8.6 percent increase in productivity.32 But the advantage that the United States has had in education over other countries is shrinking.

In spite of robust U.S. educational college and high school completion rates and a high proportion of GDP expenditures on education, the country falls in the middle of the G-8 members relative to performance on standardized achievement tests in reading, mathematics, and science. Obviously, how long a person goes to school is irrelevant when compared to what a person has learned during the years in school. One likely explanation for this problem is the fact that the United States has the greatest average spread on achievement tests of G-8 countries. The ninety-fifth percentile of U.S. students represents the highest standardized test achievement of equivalent percentile students among G-8 countries, but the fifth percentile of U.S. students represents the lowest.

The United States is generally acknowledged as having the highest-quality colleges and universities in the world.33 Increasingly, the proportion of nonnative graduate students in U.S. universities is increasing. One important boon to the U.S. economy is the fact that 70 percent of foreign-born individuals who receive their PhD’s in U.S. universities remain in the country for long-term employment.34

What HR Professionals Need to Know About Workforce Demographics

To contribute to management team discussions about the human component of work, HR professionals need to know the basic trends relative to these issues and where they can find current information. They need to back up generalizations about basic trends with specific data. With this knowledge, they may then

- Add value to strategic discussions about workforce planning.

- Understand the demographic forces that influence their firms directly as well as those that influence them indirectly through customers, shareholders, management, and employees.

- Align their HR strategies and practices to HR’s key constituents in a timely and accurate manner.

Assessment 2-3 contains a self-evaluation of the knowledge that an HR professional might need to have about workforce demographics.

ASSESSMENT 2 - 3

Knowledge of workforce demographics

Resources Regarding Workforce Demographics

With some degree of regularity, many popular business publications provide overview articles pertaining to workforce demographics and other labor trends: BusinessWeek, the Economist, Forbes, Fortune, Inc., Financial Times, Handelsblatt, and the Wall Street Journal. Many journals and popular magazines abound from every global region: Ageing and Society, American Demographics, Demography, Demographic Research, Profiles in Diversity Journal, Gender and Society, Human Resource Management Journal, International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations, International Migration Review, International Migration, Journal of Cultural Diversity, Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, Journal of Labor Research, Journal of Population Economics, Journal of Population Research, Monthly Labor Review, Population and Development Review, Review of Population Reviews, Society, and Women and Work. Ample Web sites on various aspects of demographics contain statistics, statistical summaries and conceptual reviews: CensusScope.org. (census data), www.clusterbigip1.claritas.com (segmented population data), fedstats. gov (statistics from the U.S. government), prb.org (summary population data), BLS.gov (Bureau of Labor Statistics), Demography.anu.edu.au (demographics and population studies), gksoft.com/govt (government studies), esa.un.org (United Nations population studies), Libr.org/wss/WSSLinks (gender studies), and Sciencedirect.com (general portal for scientific research).

Business Realities and HR Responses

In today’s fast-changing world, it is imperative that HR professionals be “at the table.” This requires more than simple familiarity with HR issues or internal operations; it requires knowledge about the driving forces that shape the fundamental nature of business. For credibility, HR professionals must not only understand the logic of the external trends, they must also have data to back up their positions and must know where to find such data. The key areas that frame much of today’s business realities include technology, economic trends, demographics, and the global environment in which each of these exist. With this knowledge foundation, HR professionals are prepared to begin the discussions about customers, shareholders, management, and employees.