4

New Approaches to Old Problems

Hitting the Bull’s-Eye with Enterprise 2.0

Chapter 3 showed that emergent social software platforms (ESSPs) come in many forms and can be used in a wide variety of ways. Because of this, it might seem that Enterprise 2.0 is such a diverse phenomenon that it can’t be boiled down at all, and will mean something different for every organization. But this is not the case. Even though there are a great many tools available, and even though every deployment of them will be unique, there are deep similarities.

The Concept of Tie Strength

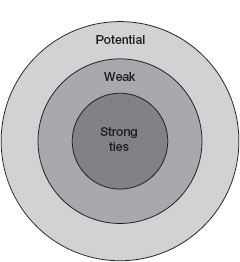

To reveal these similarities, this chapter uses the concept of “tie strength” between people. Some deployments of ESSPs are intended to support ties that are already strong, while others are aimed at ties that are weak, or even nonexistent. The case studies in chapter 2 provide examples of the four different levels of tie strength, which this chapter presents as rings in an “Enterprise 2.0 Bull’s-Eye.” Awareness of this bull’s-eye helps leaders decide where they want to focus their organization’s Enterprise 2.0 efforts.

When observers have chronicled the world of work, they have often focused on relatively small groups of close-knit colleagues. This was certainly true of the landmark Hawthorne studies conducted from 1927 to 1932 by Elton Mayo and his associates at Harvard Business School. This research, which gave rise to the term “Hawthorne effect,” documented the output, interactions, and attitudes over time of a team of assembly workers in a factory outside Chicago. The Hawthorne studies were revolutionary not only for their findings but also for their long duration and level of detail, and they established a template for much later work. 1

The tendency to focus on small groups of close colleagues extends to fictional depictions of the working world, from Herman Melville’s 1853 novella Bartleby, the Scrivener to the British and then American television series The Office. All of this work builds on, and reinforces, the perception that the interesting aspects of work are the activities and interactions of close colleagues.

A landmark paper in sociology, written over thirty-five years ago, offers a very different perspective. In 1973 Mark Granovetter’s “The Strength of Weak Ties” appeared in the American Journal of Sociology. SWT, as the paper came to be known, advanced a novel theory, which Granovetter himself summarized in a follow-up article written ten years later: “The argument asserts that our acquaintances (weak ties) are less likely to be socially involved with each other than are our close friends (strong ties). Thus the set of people made up of any individual and his or her acquaintances comprises a low-density network (one in which many of the possible relational lines are absent) whereas the set … consisting of the same individual and his or her close friends will be densely knit (many of the possible lines are present).” 2

Granovetter also laid out the critical implications of this assertion:

The overall social structural pictures suggested by this argument can be seen by considering the situation of some arbitrarily selected individual—call him Ego. Ego will have a collection of close friends, most of whom are in touch with one another—a densely knit clump of social structure. Moreover, Ego will have a collection of acquaintances, few of whom will know each other. Each of these acquaintances, however, is likely to have close friends in his own right and therefore to be enmeshed in a closely knit clump of social structure, but one different from Ego’s. The weak tie between Ego and his acquaintance, therefore, becomes not merely a trivial acquaintance tie but rather a crucial bridge between the two densely knit clumps of close friends… these clumps would not, in fact, be connected to one another at all were it not for the existence of weak ties (emphasis added). 3

A tidy summary of SWT’s conclusion is that strong ties are unlikely to be bridges between networks, while weak ties are good bridges. Bridges help solve problems, gather information, and import unfamiliar ideas. They enable work to be accomplished more quickly and more effectively. The ideal network for a knowledge worker probably consists of a core of strong ties and a large periphery of weak ones.

SWT made a fundamental contribution to the discipline (as of July 2008 it had been cited by others an astonishing 7,100+ times, according to Google Scholar) because it focused attention on a previously ignored area, and because it articulated tight and testable hypotheses about why weak ties were so valuable.

In SWT Granovetter didn’t focus on work environments, but later research explored whether his hypotheses and conclusions apply within companies. Morton Hansen, for example, found that weak ties helped product development groups accomplish projects quickly. Hansen, Marie Louise Mors, and Bjorn Lovas further showed that weak ties helped by reducing information search costs. And Daniel Levin and Rob Cross found that the benefits of weak ties were amplified if knowledge seekers trusted that the information sources in question were competent in their fields. 4

This research revealed that Granovetter might well have been talking about companies when he wrote that “… social systems lacking in weak ties will be fragmented and incoherent. New ideas will spread slowly, scientific endeavors will be handicapped, and subgroups separated by … geography or other characteristics will have difficulty reaching a modus vivendi.” 15

By 2007, the executives at Serena Software (the second of the case studies in chapter 2) were becoming worried that their company was devolving into exactly this kind of dysfunctional and inefficient social system. The company had grown largely by acquisition, had many offices around the world, and had a workforce consisting of 35 percent telecommuters—people who rarely if ever came into an office. In these circumstances it could be difficult for Serena employees to form even weak social ties with one another. Granovetter’s work implies that the lack of such ties would impede more than Serena’s ability to build a healthy corporate culture; it would also impede its employees’ ability to accomplish important and novel work.

A later body of influential sociological research focused not on ties, but on their absence. Like SWT, Ronald Burt’s 1992 book Structural Holes analyzed social networks in a novel way and became heavily referenced (with more than four thousand Google Scholar citations by July 2008). Burt defined a structural hole as “a separation between nonredundant contacts,” which he in turn defined as contacts that don’t “lead to the same people, and so provide the same information benefits.” 6

In Burt’s formulation structural holes are sometimes filled by people, and sometimes not. When they are not, information can’t flow from one human network to the other. Ties span holes, and weak ties can be particularly valuable in this regard, but there is no guarantee that all structural holes, even the most important ones, will be filled. Burt’s book emphasized that structural holes can be valuable to an individual if she can establish contacts that span them. When she accomplishes this task, she provides information benefits to both of the previously isolated networks and so increases her “social capital.”

Unspanned structural holes may provide opportunities and be valuable from an individual’s perspective, but from an enterprise perspective they are nothing but bad news. Because they prevent information from flowing, unspanned holes lead to the fragmented and handicapped social system described by Granovetter. As the federal commissions on the 9/11 attacks and the intelligence failures with regard to Iraqi weapons of mass destruction made clear, U.S. intelligence agencies were just such a system before 9/11, and even afterward. Many reports and news stories referred to the agencies’ failure to “connect the dots” of available intelligence about the threats facing the country, unconsciously using precisely the imagery of social network analysis. In this case the dots were both pieces of information and the intelligence analysts who held this information. When these analysts were members of networks whose structural holes were not spanned, vital information did not flow as it needed to. In the language of network sociologists, the U.S. intelligence community was a “non-dense” network, that is, one in which few of the potential ties among members had been converted into actual ones. In other words, it was a network riddled with structural holes that were not spanned.

The Enterprise 2.0 Bull’s-Eye

The concepts of interpersonal ties and structural holes provide a way to frame the benefits of Enterprise 2.0 and to show how popular ESSPs differ from one another. Consider the prototypical knowledge worker inside a large, geographically scattered organization (all of what follows also applies to smaller and more centralized organizations, but probably to a lesser extent). She has a relatively small group of close collaborators; these are people with whom she has strong professional ties. Beyond this group is another set of people—those she has worked with on a past project, coworkers with whom she interacts with periodically, colleagues she knows via an introduction, and the many other varieties of “professional acquaintance.” In Granovetter’s language, she has weak ties to these people.

Beyond this group is a still larger set of fellow employees who could be valuable to our prototypical knowledge worker if only she knew about them. These are people who could keep her from reinventing the wheel, answer her pressing questions, point her to exactly the right resource, tell her about a really good vendor or consultant, let her know that they were working on a similar problem and had made some encouraging progress, or perform any of the other scores of helpful activities that flow from a well-functioning tie. By the same token, if our focal worker is a person of goodwill, she could help many other people in the company if her existence, work experiences, and abilities were more widely known.

But because the structural holes between the focal worker and the members of this large group have not been spanned by a person, the interpersonal ties are only potential, not actual. The people remain unaware of each other and so can’t put their nonredundant networks in contact with one another. While this may represent a hole-spanning opportunity for an individual within the organization, from the leader’s perspective it’s just a shame and a loss. The leader would prefer all networks to be interconnected, as long as it doesn’t cost too much.

The bull’s-eye diagram in figure 4-1 is an extremely simple representation, not to scale, of the relative size of these three groups—strongly tied colleagues, weakly tied colleagues, and potential ties—from the perspective of our focal knowledge worker. The small core of people with whom she has strong ties lies at the center, surrounded by her larger group of weak ties. Potential ties are in the third ring. My intuition says that for most knowledge workers the three circles in the figure are nested accurately—that the number of potential ties, say, is greater than the number of weak ties—even if their relative sizes are not accurate.

Relative volume of different types of ties for a prototypical knowledge worker

Poor Tools for Important Jobs

Research on weak ties, structural holes, and many related concepts within social network analysis has revealed the importance of the outer two rings of the bull’s-eye. The ability to form, maintain, and exploit weak ties and the ability to convert potential ties into actual ones (either strong or weak) are both hugely valuable assets, both to individuals and to the enterprises in which they work. Our tendency to focus only on strongly tied colleagues within enterprises has given way to a broader and more useful perspective that encompasses weak and potential ties as well.

Until recently, however, few technologies were available to help people and organizations that wanted to adopt this perspective. Maintaining and exploiting weak ties and converting potential ones were human activities, conducted face to face or, more rarely, over the phone.

Earlier generations of IT helped with these activities, but not much (groupware and knowledge management were primarily intended for strongly tied colleagues). I often ask my students and audiences what pre-Web 2.0 technologies, if any, were available to help individuals keep their network of weak ties up to date on their activities. The annual family update letter that some people send out around the holidays is the best response I’ve heard. I also ask about the reverse challenge: keeping up to date on the news from one’s entire network of weak ties. I have yet to hear of a good pre-Web 2.0 technology that addressed this need.

Finally, I ask about older technologies for exploiting a network of weak ties by, for example, asking all of its members a question and hoping for a quick and helpful answer. Many of my MBA students previously worked as analysts at large consultancies and banks. They have used blast e-mails, listservs, and group instant messaging to ping their networks of weak ties with questions like, “Has anyone sized the Eastern European 3G telephony market?” or, “How many public medical device manufacturers are there, and which of them are outperforming the market?” They reported varying levels of success and satisfaction with this method and also pointed out a few of its shortcomings. E-mails are often perceived as intrusions and ignored, while instant messages can easily be missed.

At the level of potential ties, the main drawback to human-based methods for converting them into actual ties is, essentially, that these methods don’t go far enough, fast enough. Some of the people who span structural holes do so selfishly, with the explicit intent of getting paid or increasing their social capital, whereas others do so selflessly, aiming simply to connect people who otherwise wouldn’t have met. But within any sizable enterprise many, if not most, holes remain unspanned. In order to span two nonredundant networks, a person must either already be a member of both of them or make the effort to become a member. Human network spanners, in other words, need to be both well positioned and motivated—typically a rare combination.

Enterprises have long realized both the value of converting potential ties into actual ones and the deficiencies of relying on human-based methods alone to accomplish this task. Consequently, they’ve experimented with a number of technological tools aimed at the third ring of the bull’s-eye. These tools can be divided into three categories: directories, document repositories, and automated tie suggesters. Directories are essentially digital organizational white pages; they provide a listing for each person giving his or her contact data and other hopefully relevant information such as education, experience, and areas of expertise. Some of this information is generated automatically from the enterprise’s human resources systems, while some can be entered by the people themselves. Directories can be useful, but I have yet to find a large company whose employees thought that its directory captured and displayed the “right” information about people. Rather, they regarded the directory pages like most other intranet pages: static, sparse, and often out of date.

Document repositories are common at organizations like law firms and consultancies, where almost all capital is human capital and all work knowledge work. This work is typically captured in documents, including presentations and spreadsheets, which are stored in searchable repositories. Many people report that these documents are valuable not primarily for their content, but for their authors. In other words, documents point to potential ties. Many current repositories, however, do not highlight this aspect of their documents and instead focus primarily on their content.

Automated tie suggesters are information technologies that monitor knowledge workers’ computer activities (e-mail, Web surfing, and so on) for a time, identify people with similar patterns of activity, and then suggest to these people that they should form a tie. While these technologies show promise, they have not yet been widely implemented. Where they have, privacy concerns have often appeared. Many people do not want their online activities monitored and analyzed, even if it’s being done with the best of intentions.

New Tools for Strongly Tied Colleagues

In fact, there are problems with the technologies used to support unstructured collaboration even at the innermost ring of the bull’s-eye, where ties are strong. When I speak to or teach groups, I often ask people to raise their hands if they generate most of the documents they’re responsible for with a group of collaborators, rather than individually. Typically, most hands go up; evidently few reports, spreadsheets, and presentations in enterprises these days are authored by just one person. I then ask people to leave their hands up if, when generating and refining these documents, they work primarily by attaching them to e-mails addressed to all collaborators. Again, with most audiences, most hands remain in the air. Finally, I ask people to keep their hands in the air if they’re largely happy with this style of collaboration. Most hands come down.

Everyone who has collaborated this way is familiar with the two major challenges of version control and simultaneous editing. Version control refers to the fact that it’s difficult to keep track of which version of the document is the current or “correct” one. Simultaneous editing, that is, two or more people working separately on the document at the same time, inevitably leads to incompatible versions that must somehow be reconciled, usually by painstaking, side-by-side comparisons. It’s virtually impossible to prevent simultaneous editing when collaborators are all working with their own copies of documents, copies that have been sent to them as e-mail attachments.

Wikis, which elegantly address the challenges of version control and simultaneous editing, are effective tools to support the work of strongly tied colleagues. (The first wikis were for text editing, but wiki-like tools have also been developed for spreadsheets and presentations.)

Wikis solve the version control problem by keeping all contributions from all collaborators in one central repository, making it impossible for different versions to exist on the hard drives of individuals’ computers. Simultaneous editing becomes an issue with a wiki only if it’s truly simultaneous—if two people are editing the document at exactly the same time. There are a few approaches for dealing with this situation. MediaWiki, the wiki software that underlies Wikipedia, alerts users when they attempt to save the page they’re working on and shows them the edits made by others since the last save. Google Docs, a wiki-like word processor from Google, comes close to showing others’ edits as they happen.

At VistaPrint, the direct marketing company whose case study opened chapter 2, senior software engineering manager Dan Barrett employed a wiki to capture and spread knowledge. 7 To begin, he set himself the task of documenting everything a new technical hire would need to know in order to be effective within the company. He asked himself and his colleagues questions like, “What would an engineer need to know on day 1 here? Within the first week? During the first month?” As he listened to and recorded answers, Barrett drew up lists of knowledge topics such as department names and attributes of software used within the company.

After about three months he had identified approximately one thousand topics. Most of these topics were interrelated, so Barrett also kept track of many types of relationships, including similarities (“Computer” and “PC”), hierarchies (“Operating systems” and “Windows”), and more general associations (“World Wide Web” and “Browser”). He did not attempt to become an expert on all of these topics, or to define the content that should go within them.

Barrett knew that VistaPrint would use IT to help capture knowledge on these topics, but as he asked questions and built topic lists, he was not trying to design or specify any particular system. He was simply working to understand the knowledge a new technical employee needed to have, and how the bits and pieces of this knowledge related to one another.

During this process he came to believe that wiki technology was well suited to capturing and organizing knowledge among VistaPrint’s engineers, in part because the philosophy underlying wiki contribution was similar to the company’s approach to modifying code. As Barrett explained:

Lots of companies “lock down” their code bases and give only a few people the ability to make changes. We take a very different approach. Any of our engineers can “check out” a piece of code, then “check in” an updated and hopefully improved version. All of these actions are logged, so that if something stops working we know exactly who worked on it, or who worked on code that interacts with it, and when they did so. If necessary, we can always revert back to the previous version of the code—the one that was in place prior to the appearance of the problem. We believe that you ensure high code quality NOT by locking it down in advance, but instead by giving lots of people the opportunity to improve things while maintaining a tight audit trail.

Wikis work exactly the same way. Anyone can add something or change something, and all edits are tracked and can be reverted. Quality comes from letting lots of people contribute with few up-front rules, but maintaining the ability to see who did what, and undo anything that turned out not to be a good contribution. So wikis are a natural fit for us; they correspond well to the way we’re used to working.

Barrett also liked a few other aspects of wikis. First, he considered them to be almost “frictionless” to use; a participant could add, edit, or search for information almost immediately, with very few steps or mouse clicks. He found that many other group-level technologies, in contrast, required their users to “jump through a lot of hoops” before they could do anything valuable. Second, he liked how participants could add structure to wikis by linking and tagging. Barrett had worked with many classic KM systems and felt that the hierarchical structure they imposed on all content was not appropriate for an organization’s knowledge. Linking and tagging were not imposed and were not hierarchical; instead, they reflected people’s understanding of how topics related to one another. Finally, he liked how wiki software such as MediaWiki (the application that Wikipedia was built on top of) could be integrated with other programs such as VistaPrint’s bug-tracking software.

Barrett installed MediaWiki software at VistaPrint with the goal of getting the company’s engineers to enter their accumulated knowledge into it. He knew, however, that it would be difficult to persuade these knowledge workers to take time out of their busy days to do so. To make it as frictionless as possible for them, therefore, he preconfigured the wiki with articles devoted to the thousand knowledge topics he had recorded and with links between those articles that reflected the relationships among them. The existence of predefined articles meant that someone with knowledge about “bug tracking” or “e-commerce Web site” would immediately know where to record this information. Engineers were free to modify or extend this initial structure, but Barrett felt that it was important for the wiki to have an initial structure.

He added no content to these articles himself. Instead, he encouraged his colleagues to do so. When he received an e-mail whose content was relevant to the wiki, he replied to the sender with a request to add that content to the wiki, including a link to the appropriate page. He found that people were almost always willing to take the couple of minutes required to put the information on the wiki, and in many cases even added to it. This content might not be beautifully formatted, but Barrett was not concerned about this. As he put it “information is more important than layout.”

As the company’s engineers kept adding content, Barrett assumed the role of editor in chief of the wiki—formatting contributions, moving content around, adding links and tags, and generally making sure that it was easy to read, navigate, and search. He found the combination of constantly nudging his colleagues to add content, then editing their contributions to be a powerful one. As the wiki grew, it became useful to the company’s engineers, who in turn became more likely to contribute to it. This virtuous cycle led to rapid growth, and by the summer of 2008 the wiki had grown to include populated articles (ones with at least some text) on approximately eleven thousand topics. Employees had used tags to place these articles into more than six hundred categories, and Barrett believed that all of the company’s engineers both used the wiki and had contributed content to it. Of the eleven thousand topics, he estimated that all but five were directly relevant to VistaPrint’s business; the rest were social.

In August 2008 VistaPrint was ready to roll out use of the wiki well beyond the engineering department and to make it the knowledge repository for the entire company. Barrett was optimistic that this effort would be successful, even though the MediaWiki software did not support WYSIWYG (“what you see is what you get”) editing and was therefore a bit more difficult to use than word-processing programs such as Microsoft Word. Initial experiments showed him that most VistaPrint employees could learn to edit effectively in MediaWiki, with about forty-five minutes of training. However, because most of these employees still did much of their work using programs such as Word, Excel, and PowerPoint, the company was also planning to deploy Microsoft’s collaboration suite, called SharePoint.

New Tools for Weakly Tied Colleagues

Wikis and similar group-based technologies for creating and modifying documents are excellent technologies at the center of the bull’s-eye, where collaborators are strongly tied. At each of the outer two rings of the bull’s-eye, a different ESSP also becomes valuable. As the example of Serena software shows, social networking software (SNS) like Facebook is a powerful tool for connecting weakly tied collaborators and facilitating their interactions.

Serena, the company that was the subject of the second case study in chapter 2, used Facebook to help build a stronger and more consistent corporate culture. In October 2007 Serena decided to largely walk away from its current intranet and replace it with Facebook. The company did not abandon its intranet because of expense—the intranet leveraged Serena’s own content management system and so was very cheap to maintain—but because it was static, dull, and not heavily consulted.

CEO Jeremy Burton and chief marketing officer René Bonvanie, who were heavy users of SNS on the Web, realized that it had just the opposite properties: it was dynamic, interesting, and addictive for many people. Facebook gave its users tools to assemble a network of people, stay on top of what these people were doing, and provide their own updates to the network. Serena’s executives realized that these were just the activities needed to create a stronger sense of community within the company.

Serena held the first of its “Facebook Fridays” in November 2007. These voluntary sessions were intended to make employees comfortable with the software and its uses. Initial investigations had shown that people were particularly interested in pictures of their colleagues, since in many cases they had no idea what a coworker looked like. On the first Facebook Friday people were encouraged to bring their digital cameras and come to work dressed in a way that showed something about themselves. Burton, an automobile racer, dressed in his racing suit, while CFO Robert Pender arrived in golf clothes. People in the offices took pictures of one another and uploaded them, while those who worked from home dressed up and took pictures of themselves; within twenty-four hours, more than half the company’s employees had pictures as part of their Facebook profile.

Serena did not build or buy a private version of Facebook; instead, it used the standard public application available on the Web. However, many employees wanted to keep at least some of the information in their profiles private and unavailable to everyone on the Internet. To educate the workforce about Facebook’s privacy tools and options, the company brought in to its larger offices teenagers (usually the children of employees) who were expert Facebook users to conduct training and answer questions.

After the pictures were up, the most commonly used Facebook feature at Serena was the status update, which allowed users to post a short message about what they were doing. This update was then made visible to all members of the user’s network. As vice president Kyle Arteaga explained:

At any given time I know as much about my colleagues as they want to share via Facebook, for example John B. from IT “is sucking on a starbucks, yummy,” and Peter S. from Support “is gesturing evily at the rain clouds.”

So I now have context when I next speak to each of them. I actually need to call John about a project we are working on later today and I will bring up his Starbucks comment. Peter and I work together quite a bit and he is based in London, so having lived there recently I can commiserate with him about the weather. 8

Facebook use contributed to the broader goal of introducing Serena’s workforce to Web 2.0 and its culture of openness and information sharing. Unless employees used the site’s privacy tools to keep information hidden, all that they posted for their colleagues was also visible to all Facebook members throughout the Internet. Arteaga explained the rationale for this:

We want customers, vendors, partners, prospective employees, and anyone else who is interested to be able to easily find out more about our company. We want to be approachable and find that the best way to do this in today’s world is through viral means …

We share the belief that work and home lives are starting to become very intertwined. The separation that used to be prevalent is becoming less and less so with the ubiquity of BlackBerrys, mobile phones in general, and social networking sites. This is why we encourage employees to determine for themselves what their level of comfort is with this increasing transparency (e.g., learn how to create slices of your profile so that you share the right information with the right people). We also realize that many (particularly millennials) only know complete transparency, and that with complete transparency the traditional buttoned-down corporate culture that has thrived for so long may well be dismantled …

Concern[s have come up] about questionable postings on people’s profile and/or related Facebook blogs. While we can certainly see why people might take offense at certain topics and/or opinions, we have not changed our communications policy despite our social networking initiatives. At the end of the day, we trust our employees to use common sense. We consistently tell them “be smart, do what you think is right.” Of course, everyone’s parameters are different. But we see no reason why we should put out specific Facebook guidelines on what you can and can’t post, it’s not as if we put out guidelines on what people say on the weekend at their neighbor’s barbecue or at their child’s piano recital.

Facebook participation was voluntary, but became quite widespread at Serena. By the end of 2007 the company estimated that 90 percent of its employees had created a profile. Approximately 25 percent of Serena’s Facebook users were active, meaning that they visited the site multiple times a day, while another 50 percent accessed Facebook at least three times a week.

In 2008 the company began using Facebook to host videos and other materials related to its marketing campaigns and to announce, popularize, and recruit for its corporate social responsibility efforts such as Green Day and Children in Need.

In September 2008 Arteaga reported on some of the concrete benefits arising from Serena’s heavy use of Facebook:

We are holding our annual user event next week … Normally we have five hundred people in attendance. This year attendance is double.

The main reason for this is Facebook. While our traditional customer base is still coming, we were able to extend to a much wider set of interested parties by exclusively using social networking. We asked employees to put links to the event in their status updates for the past month, we asked them to post the conference site in their profile and to join the conference group.

As a result we have five hundred new attendees, all friends of friends of friends. Not a single traditional email or outbound call went out to solicit this new group …

On top of this, we have also received many resumes of interested job seekers. In fact, I received my job via Facebook over a year ago. Our former head of sales recruited me when he found out [via Facebook] that I was leaving [my previous job]. Several of my colleagues were hired in similar fashion. And of course, quite a bit of networking has taken place via Facebook at all levels. Our head of support regularly converses with his support peers in other companies through a Facebook group he started.

Facebook was not the first SNS on the Web, and several other social networking tools are currently available. Some of them, such as LinkedIn, are specifically intended for business purposes. So why did Serena choose Facebook? Facebook has a few attributes that combine to make it particularly appropriate for the second ring of the bull’s-eye, which contains large numbers of weakly tied collaborators.

First, it can “hold” large numbers of weak ties for each user. Facebook calls each contact a friend, and members can easily accumulate hundreds or even thousands of friends. Members can search their list of friends to find a specific person and then go to that person’s profile page for contact data and any other information they’ve decided to post. In short, Facebook serves as a large and rich address book for weak ties.

Second, it lets members post many kinds of update, which it then communicates to friends. All Facebook members have a status field, which is simply a short text box. Members can type whatever they want in this box and change it as often as they like. The snippets of information from coworkers that Kyle Arteaga cited in the Serena case study—including “is sucking on a starbucks, yummy” and “is gesturing evily at the rain clouds”—are examples of status updates. Facebook members can also post photos, videos, links to Web pages, longer notes, and other types of content and pointers to online content.

These same features mean that Facebook is a tool members can use not only to update their friends but also to stay in touch with what all of these friends are doing. In other words, the site is not just for broadcasting, but also for receiving many individuals’ broadcasts. All members’ home pages center on a chronological list of all their friends’ updates, with the most recent at the top. A quick perusal of this list lets users know what their friends are doing.

The activities of both broadcasting and receiving on Facebook are technically trivial for users, and quickly accomplished. It takes no skill and very little time to update and share information with friends, and to find and consume this information. As a result, an SNS like Facebook holds out an intriguing promise: the ability to let people build larger social networks than would otherwise be possible.

In a series of articles in the early 1990s, the anthropologist Robin Dunbar compared data about the neocortex (a region of the brain) volumes of various primates with the maximum sizes of their social groups. The two were tightly related, causing Dunbar to hypothesize that “animals cannot maintain the cohesion and integrity of groups larger than a size set by the information-processing capacity of their neocortex.” He used the primate data to estimate the theoretical maximum social group size for humans, calculating that it was somewhere between 100 and 230, with a most likely value of 150. “Dunbar’s number,” as this has come to be known, represents a ceiling on the number of people with whom an individual can maintain stable social relationships. As Dunbar put it, “The figure of 150 seems to represent the maximum number of individuals with whom we can have a genuinely social relationship, the kind of relationship that goes with knowing who they are and how they relate to us. Putting it another way, it’s the number of people you would not feel embarrassed about joining uninvited for a drink if you happened to bump into them in a bar.” 9

By reducing the amount of time and effort required to track other people’s social activities, an SNS can potentially increase the number of people with whom one can have a true social relationship. As Carl Bialik reported in a November 2007 post to his Wall Street Journal blog, “Dunbar … says that [social-networking sites] could ‘in principle’ allow users to push past the limit. It’s perfectly possible that the technology will increase your memory capacity,” he says. 10

Some people, of course, are not comfortable sharing all of their SNS information and updates with their entire network, and Facebook’s core concept of friends is in some ways incompatible with hierarchical relationships within an enterprise; a boss, after all, is not the same thing as a friend. Facebook, however, has many different privacy settings, which allow users to control the information that they share and receive. Teenagers, with their active and fluid social lives, are often quick to master these settings, which explains why Serena asked the children of some of its employees to lead training within the company on privacy and SNS.

Facebook currently lets members ask their network a question and collects the answers on one globally visible page. I imagine that successful enterprise Facebook equivalents will have more advanced tools to allow members to exploit their networks actively by asking them for assistance in many different ways. I also imagine that they’ll let users post answers to their most frequently asked questions and then simply point seekers to this resource.

It seems clear that Facebook and similar technologies, when deployed within an organization, blur the border between an individual’s personal and professional lives. This border will have to be negotiated and monitored as enterprise SNS becomes more popular. Serena’s approach was to encourage employee participation, to set few hard-and-fast rules, and to leave most decisions in the hands of the individual. To date, the company has been pleased with the results of this approach. Because Serena grew by acquisition and is geographically highly dispersed, most of its employees are only weakly tied. The company has found the Internet’s freely available SNS extremely well suited to maintaining and often strengthening these ties. Facebook, in essence, did what the company’s own intranet couldn’t do; it helped knit the enterprise together more tightly.

New Tools for Converting Potential Ties

ESSPs have also knit the U.S. intelligence community more tightly together by converting some potential ties into actual ones. In chapter 2 the case study of the IC’s failure to connect the dots prior to 9/11 closed with the announcement of the Galileo Awards, an initiative to surface new and innovative ideas. The winner of the first Galileo Award was “The Wiki and the Blog: Toward a Complex Adaptive Intelligence Community,” by Calvin Andrus, the chief technology officer of the Center for Mission Innovation at the CIA. As Andrus’s paper pointed out:

The value of a knowledge-sharing Web space (wiki and blog) grows as the square of the number of links created in the Web space. There is knowledge not just in content items (an intelligence cable, for example), but also in the link between one content item and another—a link, for example, from a comment in a blog to an intelligence cable. Think of the value of a blog that links a human source cable to an intercept cable to an image cable to an open source document to an analytic comment within the context of a national security issue. When such links are preserved for subsequent officers to consider, the value of the knowledge-sharing Web space increases dramatically. When 10,000 intelligence and national security officers are preserving such links on a daily basis, a wiki and blog system has incredible intelligence value …

Once the Intelligence Community has a robust and mature wiki and blog knowledge-sharing Web space, the nature of intelligence will change forever … The Community will be able to adapt rapidly to the dynamic national security environment by creating and sharing Web links and insights through wikis and blogs (emphasis in original). 11

In another paper that won an honorable mention in the Galileo contest, Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) analyst Michael Burton stressed the value of free and easy platforms for contribution, and mechanisms such as linking to let structure emerge and improve navigability. 12

In an article in the New York Times Magazine, writer Clive Thompson presented a scenario for how ESSPs could have helped prevent the 9/11 attacks:

With Andrus and Burton’s vision in mind, you can almost imagine how 9/11 might have played out differently. In Phoenix, the F.B.I. agent Kenneth Williams might have blogged his memo noting that Al Qaeda members were engaging in flight-training activity. The agents observing a Qaeda planning conference in Malaysia could have mentioned the attendance of a Saudi named Khalid al-Midhar; another agent might have added that he held a multi-entry American visa. The F.B.I. agents who snared Zacarias Moussaoui in Minnesota might have written about their arrest of a flight student with violent tendencies. Other agents and analysts who were regular readers of these blogs would have found the material interesting, linked to it, pointed out connections or perhaps entered snippets of it into a wiki page discussing this new trend of young men from the Middle East enrolling in pilot training.

As those four original clues collected more links pointing toward them, they would have amassed more and more authority in the Intelink search engine. Any analysts doing searches for “Moussaoui” or “Al Qaeda” or even “flight training” would have found them. Indeed, the original agents would have been considerably more likely to learn of one another’s existence and perhaps to piece together the topography of the 9/11 plot. No one was able to prevent 9/11 because nobody connected the dots. But in a system like this, as Andrus’s theory goes, the dots are inexorably drawn together. 13

The IC already had an intranet environment well suited to deploying ESSPs like wikis and blogs. This environment was actually a group of networks, each open to people with the appropriate security clearances. Construction on these networks was begun in 1994, and by early 2005 separate top secret, secret, and unclassified networks spanned all the agencies of the IC (these networks were separate from each other for security purposes). Google’s search technology had been deployed across all of these networks by that time.

In early 2005 Andrus spoke about his ideas to a group of analysts who advised the CIA on technology issues. Sean Dennehy, a member of that group, was skeptical about the value of ESSPs for intelligence analysis but decided to investigate them. After spending time on Wikipedia, he was impressed by that community’s ability to generate accurate and valuable information, to discuss the process of generating that information (these discussions were captured in the “talk” page that was part of each article), and to keep a record over time of all of its work (Wikipedia’s underlying MediaWiki software, like most wiki applications, archives a copy of every version of every page). Dennehy felt that good intelligence analysis required exactly these capabilities, as well as greater collaboration than had historically been the case within the IC.

Dennehy and Andrus approached the director of national intelligence (DNI)’s Intelligence Community Enterprise Services (ICES) group, which was already seeking approval to have MediaWiki software deployed at each of the three levels of security throughout the IC. Dennehy worked on Iraq issues, but he saw that it would be counterproductive for the IC to have separate wikis for each topic, or indeed for each agency. He and Andrus instead advocated for something very much like Wikipedia: a single wiki with pages devoted to any and all topics of interest. DNI/ICES, essentially an IT support organization, needed champions within the mission areas of the IC to test out and advance the new capability. Dennehy and Andrus willingly agreed to play this role. The ESSP resulting from these interactions, called Intellipedia, was prototyped in November 2005 and officially announced to the IC in April 2006.

Communitywide blogs had been launched in March 2005. One of Don Burke’s colleagues read a blog entry about the nascent Intellipedia in early 2006 and mentioned it to him. Burke, who worked in the CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology, had independently reached many of the same conclusions as Andrus and Dennehy about the shortcomings of current approaches to analysis and how to address them. The 130th person to edit Intellipedia, he quickly came to see the technology’s potential. He and Dennehy interacted and collaborated using the wiki for several months. Even though both were longtime CIA employees and worked in the same building, they had never met and did not know each other before using Intellipedia.

By April 2006, Burke and Dennehy had been freed of their other duties to concentrate on popularizing and curating Intellipedia. They began to travel frequently, speaking to interested decision makers and groups about Intellipedia and the IC’s other ESSPs. They also established a five-day sabbatical program for analysts interested in learning how to use the new technologies. In their sabbatical curriculum and presentations the two Intellipedians stressed three core principles:

• Work at the Broadest Possible Audience. To respond to the DNI’s “Responsibility to Provide” guidance, it is imperative that we challenge ourselves to work in the collaborative space with the broadest possible audience. We define “broadest possible audience” by the broadest network to which an individual has single-click access. Where sensitivity issues start presenting themselves, we encourage building “basecamps” of information in the broader audience and then only moving in to more restrictive space for the sensitive information. This is feasible with these tools because of the ease with which users can create links between the environments … a process we call creating “breadcrumbs.” The network can then control access. If an interested party has access, they will be able to follow the link. If they don’t, they at least know more information exists and they can begin following the breadcrumb if it is important enough for them to do so.

• Work Topically, Not Organizationally. This principle should be applied when the article is first given a title and every time a contributor edits the page content. When working topically, each organization can add what they know to a common page. So instead of having a CIA page on Fidel Castro and an NGA page on Fidel Castro, we simply have an organizationally neutral page called Fidel Castro onto which everyone contributes their information.

• Replace Existing Processes. We are all very busy and we don’t have time to take on new duties. We advocate that individuals and organizations look for processes that they can replace with these new tools. For instance, users must compile and synthesize a lot of information. Instead of the traditional process of working individually to gather their data in personal shared drives, folders, and work documents, they can replace that process by working in the wiki. Instead of using email to debate an idea, they can use blogs. Instead of using their browser’s “favorites” list, they can use social tagging. Instead of storing files in a shared folder behind a firewall that is not indexed by search engines, they can use Inteldocs. This is called moving from “channels” to “platforms.” A platform is a shared space where information can be easily linked, searched, tagged, etc. So, when a new analyst comes onboard and are asked to write about insurgency, they can find previous discussions and debates on the topic. 14

Over time other ESSPs, in addition to blogs and Intellipedia, were deployed across the IC. These included applications for sharing and commenting on photos and videos, and for adding tags to online content. Because of the IC’s unique requirements for functionality and security, these pieces of software were developed internally.

In February 2008 the Knowledge Laboratory of the DIA published observations and conclusions resulting from a set of fifteen interviews conducted with agency analysts about their use of Intellipedia and the IC’s other ESSPs. It concluded, “The results suggest that Intellipedia is already impacting the work practices of analysts. In addition, it is challenging deeply held norms about controlling the flow of information between individuals and across organizational boundaries.” One interviewee said that “[We] are seasoned enough to know this isn’t just a piece of software—this could change the way we’re doing business, and to me this is the antithesis of the way we used to do things.” 15

Although the Intellipedia wiki is probably the IC’s best-known social software, blogs have also been important, particularly at the third ring of the bull’s-eye. Just as SNS strengthens weak ties, blogs have several properties that make them well suited for converting potential ties into actual ones. First, they are easy to update; it takes little time and virtually no technical expertise to create a new post. This allows people to, in the words of blog pioneer Dave Winer, “narrate their work”—to describe what they’re doing in a way that’s not burdensome, yet is instantly and universally visible.

Second, most modern blogs are configured so that each update, also called a post, can be viewed or referenced as a separate Web page (an attribute called permalinking). So while a blog usually appears as a long page of short posts, it’s also a collection of many short pages, each one constituting a post. This means that if I want to refer to another blogger’s work when I’m writing my own blog, I can be quite precise. I don’t have to link to the blog as a whole; I can instead link to exactly the post of interest, even if it’s only a sentence or two in length.

Finally, blogs are permanent collections of posts. Even though all posts aren’t always visible on the main page, they do not vanish or expire, but persist over time. They can be located by people and search engines, and links to them continue to work.

Because of these properties, a blog is well suited to capturing whatever a worker wants to record and broadcast over time. This can include both the process and the output of knowledge work—finished products (reports, analyses, conclusions, and so on) as well as the efforts that went into generating them. It can also include commentary, opinions, questions, stray thoughts, and the like. The blog itself is indifferent across these different types of post. Chapter 6 takes up the question of whether the enterprise as a whole should also be indifferent, or whether giving workers freeform platforms for self-expression involves substantial risks. For now, let’s assume away any such risks.

These properties make it easy for a group of bloggers to refer and point to one another’s work via links, since these will be both precise and permanent. A set of tightly interlinked blogs has two desirable properties. First, it’s easy for a person to navigate—to follow a theme, debate, or train of thought across many blogs by clinking on their links. Second, and perhaps even more important, modern search engines such as Google’s rely heavily on links. As discussed in chapter 3, links on the Web provide strong indicators of quality and relevance, and Internet searching improved dramatically with Google’s PageRank algorithm. Intranet searching can see parallel improvements if intranet content becomes heavily interlinked and if search engine technology similar to Google’s is deployed. Enterprise blogs can help fulfill the first of these two conditions.

And what’s the benefit to an enterprise of having a densely interlinked Intranet? Well, one clear advantage is that any particular piece of online content becomes easier to find via search. But Euan Semple, the manager responsible for the BBC’s early and successful adoption of ESSPs, stressed that too strong a focus on making content such as corporate documents easier to find can obscure deeper benefits. As he wrote in a blog post,

With a few rare exceptions, once you found the document it was likely to be badly written, barely relevant and out of date …

I came to believe that what people really wanted was to find someone who knew what they were talking about. Even if that “knew what they were talking about” meant knowing which document to read, why and where it was to be found. So what we did was start building online social spaces like forums, blogs and wikis in which highly contextual, subjective, complex patterns and information could start to surface about anything and everything in the business that was interesting and worth writing about.

The result was that when someone said on our forums “I need to find the official documentation on x because I am about to do y” they were usually rewarded, and very quickly, with multiple answers along the lines of “Well I found this document answered my questions because … “ pointing them at the documentation. Indeed increasingly the source they were directed to was a blog or a wiki containing up to date, contextualized information.

Having context in the question, context in the answer and the collective memory of your corporate meatspace, empowered by the mighty hyper-link, in between is hard to beat. 16

The Urban Dictionary defines meatspace as “referring to the real (that is, not virtual) world, the world of flesh and blood. Somewhat tongue-in-cheek. The opposite of cyberspace.” 17 Semple used this word to stress that answers in the BBC’s online forums came from other employees, not from effective searches of digital documents. This ESSP, in other words, was valuable not because it connected people with information, but because it connected people with other people who possessed information.

The experience of the IC and Enterprise 2.0 is similar in many ways to that of Semple and the BBC.

Many intelligence analysts have found that the greatest value of the IC’s ESSPs, including blogs, is their ability to connect people who would otherwise have remained isolated from one another. I saw this phenomenon at work during my own research on Enterprise 2.0 within the IC. Don Burke asked me to send him questions for analysts, which he then posted on his internal blog. The first of these was, “What, if anything, [do the] Enterprise 2.0 tools let you do that you simply couldn’t do before? In other words, have these tools just incrementally changed your ability to do your job, or have they more fundamentally changed what your job is and how you do it?”

Most of the responses to this question stressed the ability of ESSPs to convert potential ties into actual ones, as well as the novelty and value of this ability:

From a DIA analyst: “These tools have immensely improved my ability to interact with people that I would never have met otherwise. I have been working with the IC advanced R&D offices … since 1999, so my job was always about networking and exchanging information since DIA does not do its own internal R&D. I learned to value networking and worked extensively with representatives from industry, academia, think tanks, and IC R&D members. But it was still hit or miss as to who I would meet and how far I would get into their knowledge base (especially if tacit). In many cases, I couldn’t access anything digitally but was dependent on finding an e-mail or a phone number from someone in the IC in order to make contact … Enterprise 2.0 tools have helped considerably in exposing new information, new projects, and bringing new thought leaders … to the forefront. People that would never have been visible before now have a voice …”

From an NSA analyst: “Before Intellipedia, contacting other agencies was done cautiously, and only through official channels. There was no casual contact, and little opportunity to develop professional acquaintances—outside of rare [temporary duty] opportunities, or large conferences on broad topics. Tracking down a colleague with similar mission interests involved finding reports on Intelink or in our databases, and trying to find whoever wrote them. But establishing a rapport or cultivating exchanges of useful information this way was unlikely at best.

After nearly two years of involvement with Intellipedia, however, this has changed. Using Intellipedia has become part of my work process, and I have made connections with a variety of analysts outside the IC. None of the changes in my practices would have been possible without the software tools … I don’t know everything. But I do know who I can go to when I need to find something out. Broadening my associations outside my office, and outside my agency, means that when someone needs help, I am in a better position to help them get it.”

From an NSA engineer: “ … there’s now a place I can go for answers as opposed to data. In addition, using that data and all the links to people associated with that data, I can find people who are interested in helping me understand the subject matter. Since I’ve been involved in Web 2.0 activities, I have met many new people throughout the IC. They are a great resource for me as I continue my career. Their helpful attitude makes me want to help them (and others) in return.”

From a DIA scientist: “IC blogs allow me to connect to people that I would not otherwise know about. I can see what they are working on, and use it to make a real introduction.”

From an NSA analyst: “More importantly, I am no longer writing to satisfy my immediate supervisor, or even a single ‘customer.’ Nor I am relying on one person’s view of what is ‘needed’ by the customer. By interacting with the whole community—even those outside my target set—I am learning where my products fit in the greater scheme of the IC, and can tailor my activities to produce intelligence of the greatest value to the broadest possible audience.”

From a CIA analyst: “The first aspect that comes to mind when I contemplate how these tools have improved my ability to do my job is the ease of shar[ing] ideas and working collaboratively with intelligence professionals around the world … without leaving my desk. This is probably an incremental change—although a huge increment—because I could always do these things to a certain extent using traditional techniques (e.g. the telephone).

On the other hand, I am actively involved in an early stage project that would be impossible without these tools. The ability to link information and people together, as wikis and blogs do, makes possible an activity that I truly believe will transform our Community. The tools fundamentally altered the course of this project. I know that my example is only one of many similarly transformational activities that are germinating or will germinate when these tools reach a greater level of penetration of the IC workforce.”

From an NSA analyst: “Wikis and blogs have changed my work life significantly. It’s extremely useful to be able to post a question on my blog if I get stumped, go and work on something else, and then come back to the problem and read my peers’ responses. Usually I can pull a solution from them, which saves me time and general aggravation/hassle.”

These responses are obviously a biased sample and can’t be assumed to represent the views of the IC as a whole, but they do illustrate the ability of ESSPs to convert potential ties into actual ones.

New Tools for Interactions Between Strangers

In the Google case study in chapter 2, Bo Cowgill was interested in building a prediction market within the company but unsure how to proceed and who to work with on the project. So he used a simple social software platform that worked at the third ring of the bull’s-eye. When he returned from vacation after reading The Wisdom of Crowds, he wrote the following note on an internal online message board where employees could post their new ideas:

By aggregating the number and nature of incoming links to a webpage, Google already uses the collective genius of crowds to rank search results. “Democracy on the web works,” is part of our corporate culture. But PageRank isn’t the only way to harness the collective intelligence of large groups.

The Iowa Electronic Markets, the Policy Analysis Market, the Hollywood Stock Exchange as well as numerous academic studies have shown that large, diverse crowds of independent thinking people are better at predicting the future or solving a problem than the brightest experts among them. This is especially true when the individuals in the crowd have a personal financial stake in getting it right.

Google has exactly what such a market needs to perform well: A large, diverse user base and the ability to give financial incentives and lower barriers to entry. To some extent, Google can even ensure that our crowd thinks independently.

So, I propose creating Google Decision Markets … who wants to work on it with me? 18

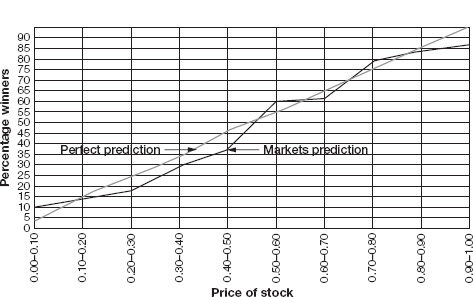

All Google engineers had “20 percent time,” the equivalent of one day a week during which they were free to pursue projects of interest within the company that were not directly related to their jobs. Cowgill was hoping to convince some Googlers to devote their 20 percent time to building a prediction market. He was also looking for quick feedback about the idea, and the message board let people rate posted ideas. As figure 4-2 shows, most respondents thought Cowgill’s idea was a good one.

Ilya Kirnos posted a reply less than ten hours after Cowgill submitted his idea: “Hey Bo, I had a similar idea and have written some code in that direction. I agree that markets have a lot of predictive power, much more so than surveys or polls for most things …” 19

Kirnos saw that Cowgill’s proposed prediction market could be used to accomplish many of the same objectives as his betting system and volunteered to help with the project, thereby converting a potential tie into an actual one. Two other Googlers also replied to Cowgill’s post and became part of the prediction market’s team.

FIGURE 4-2

Responses to proposal for a Google prediction market

Source: Peter Coles, Karim Lakhani, and Andrew McAfee, Prediction Markets at Google, Case no. 607-088 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2007).

Another respondent to Cowgill’s post was an associate of Hal Varian, a well-known Berkeley economist who consulted at Google. The respondent told Cowgill that Varian had an interest in prediction markets and had written about them in his New York Times economics column. Cowgill contacted Varian to solicit his help, and Varian began attending the group’s regular meetings. He later offered crucial advice about how to design the markets, how to implement them, and how to popularize them within the company.

After finalizing the market design, the newly formed team started programming, and completed a working version of a prediction market in less than a month. The team then decided to seek more formal support and recognition from Google, as well as funding for rewards. Some successful initiatives, including Google News and the AdSense advertising sales program, had started as employee proposals.

Cowgill’s proposal for “Google Prediction Markets” (GPM), which he submitted in December 2004, received favorable reviews and sparked interest among several executives. One of them committed to providing $10,000 from his department’s budget each quarter to fund GPM prizes.

During its first quarter of operation, which ran from April through June, there were twenty-four markets (questions) within GPM and ninety-five total different securities (answers) being traded. The team had decided on these markets by interviewing Google managers to find events of interest that would occur during the quarter. These included when a specific international Google office would open and how much demand there would be for a particular product. The team also created markets based on the company’s list of important corporate objectives, updated each quarter. In addition, the team included markets for events that would occur outside the company, such as product launches by a competitor. Finally, GPM also contained “fun” markets related to events such as the opening of the movie Star Wars: Episode III, the television reality show The Apprentice, and the NBA finals. Fun markets were intended to draw in participants and show them how easy and enjoyable it was to trade. All markets were open to all employees once they opened an account, and all Googlers could browse the markets and see their current prices and price histories, even if they didn’t have a GPM account. A randomly selected market appeared prominently on Google’s intranet. GPM documentation included an overview and list of frequently asked questions.

During the first quarter, 1,085 Googlers signed up for a trading account within GPM. A total of 7,685 trades were made, and 436,843 shares changed hands. Most of the traders came from the engineering, sales, operations, or product management functions within the company.

As data accumulated, the prediction markets team started to analyze it to learn how the markets were working, and how well. One of the main areas of interest to them, of course, was the accuracy of the markets—how well they forecast what would actually happen.

To assess accuracy, Cowgill took the final prices for a large sample of outcomes in GPM and divided them into ten ranges: 0.0–0.1, 0.1–0.2, and so on up to 0.9–1.0. If these prices really were equivalent to probabilities that the events would occur, he reasoned, outcomes priced between 0.0 and 0.1 should occur somewhere between 0 and 10 percent of the time in the real world. In a large enough sample, they should occur on average 5 percent of the time.

Price versus percentage winners

Source: Peter Coles, Karim Lakhani, and Andrew McAfee, Prediction Markets at Google, Case no. 607-088 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2007).

Cowgill compared real-world outcomes to GPM prices for each of the ten price ranges. As figure 4-3 shows, final market prices were, in general, good probability estimates.

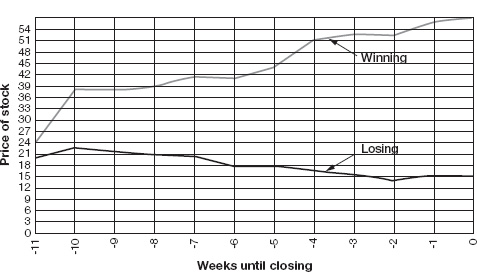

Analyses also revealed that at every point in time, even as much as ten weeks away from the closing date of the market, the most expensive outcome was the one most likely to actually occur (see figure 4-4). It seemed that GPM’s markets, in other words, could quickly and accurately distinguish among possible outcomes, identify the one most likely to occur, and attach a high price to that outcome.

Google’s prediction markets shared with all markets a fundamental property: the ability to generate highly valuable information by bringing together people who have little or nothing in common. This property of markets was highlighted by the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek in his seminal 1945 article “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” Hayek focused attention away from markets’ wealth-generating properties and concentrated instead on their ability to aggregate and transmit useful information in the form of prices:

Average price of winning and losing stock

Source: Peter Coles, Karim Lakhani, and Andrew McAfee, Prediction Markets at Google, Case no. 607-088 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2007).

The … problem of a rational economic order is … that the knowledge … of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess. The economic problem of society is … a problem of the utilization of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality.

We must look at the price system as such a mechanism for communicating information if we want to understand its real function … The most significant fact about this system is … how little the individual participants need to know in order to be able to take the right action … It is more than a metaphor to describe the price system as a kind of machinery for registering change, or a system of telecommunications which enables individual producers to watch merely the movement of a few pointers, as an engineer might watch the hands of a few dials, in order to adjust their activities to changes of which they may never know more than is reflected in the price movement …

The marvel is that in a case like that of a scarcity of one raw material, without an order being issued, without more than perhaps a handful of people knowing the cause, tens of thousands of people whose identity could not be ascertained by months of investigation, are made to use the material or its products more sparingly; i.e., they move in the right direction …

I have deliberately used the word “marvel” to shock the reader out of the complacency with which we often take the working of this mechanism for granted. I am convinced that if it were the result of deliberate human design, and if the people guided by the price changes understood that their decisions have significance far beyond their immediate aim, this mechanism would have been acclaimed as one of the greatest triumphs of the human mind. 20

In his 2006 book The Undercover Economist, journalist Tim Harford provided a concrete example of the marvel Hayek described:

[In a perfectly competitive market] every product would be linked to every other product through an ultracomplex network of prices, so that when something changes somewhere in the economy (there’s a frost in Brazil, or a craze for iPods in the US) everything else would change—maybe imperceptibly, maybe a lot—to adjust. A frost in Brazil, for example, would damage the coffee crop and reduce the worldwide supply of coffee … In Kenya, coffee farmers would enjoy bumper profits and would invest their money in improvements like aluminum roofing for their houses; the price of aluminum would rise and so some farmers would wait before buying….

That may seem like a ridiculous hypothetical scenario. But economists can measure and have measured some of these effects: when frosts hit Brazil, world coffee prices do indeed rise, Kenyan farmers do buy aluminum roofing, the price of roofing does rise, and the farmers do, in fact, time their investment so that they don’t pay too much. Even if markets are not perfect, they can convey tremendously complex information. 21

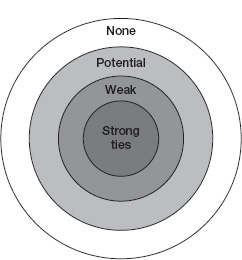

The examples of markets in general and prediction markets in particular indicate that the Enterprise 2.0 bull’s-eye should have a fourth ring—one that encompasses people who are neither current nor potential ties. In figure 4-5 this new outermost ring is labeled “none,” and the people in it are not necessarily ever going to form valuable ties, either strong or weak, with our focal knowledge worker; they are professional strangers. All the people in this ring, however, can productively interact with one another in markets, and in doing so they can generate valuable information in the form of prices.

Relative volume of different types of ties for a prototypical knowledge worker, updated

Updated to include people with whom the prototypical worker will not ever form a tie; these people are within the ring labeled “None.” Prediction markets are an ESSP that allows untied people to interact.

The traders in Google’s market and in Internet prediction markets such as the Iowa Electronic Market and the Hollywood Stock Exchange have demonstrated an ability to collectively generate accurate predictions about a wide range of events. The technologies they use to do this have all of the attributes of an ESSP. Trading in a market is very similar to the activities of linking and tagging described in chapter 3; they are all self-interested individual actions that yield substantial group-level benefits. Corporate prediction markets like the one at Google are ESSPs that can be productively used by people who are strangers—and will remain so.

The complete four-ring bull’s-eye picture shows that Enterprise 2.0 is valuable at any level of tie strength, from strong to nonexistent. The four case studies presented at the outset of this book were arranged by ring, starting at the innermost with VistaPrint’s close colleagues and moving out to untied traders in Google’s prediction market. I arranged them this way to illustrate that the prototypical ESSP differs by ring, with wikis for strongly tied collaborators, SNS for weakly tied ones, a blogosphere to convert potential ties into actual ones, and prediction markets for untied people. These tools can, of course, be valuable at other rings as well; strongly tied colleagues, for example, can all trade in a prediction market, and the Intellipedia wiki has helped intelligence analysts convert potential ties into actual ones. I place them at different rings of the bull’s-eye in order to stress that the various ESSPs are not all essentially the same, and that they don’t all do the same things or have the same effects when deployed within an organization. Instead, they are useful in quite different ways at each successive ring of the Enterprise 2.0 bull’s-eye.