Introduction

This book is about strategy creation and implementation. A good strategy matched with outstanding implementation is every company’s best assurance of success. It is also an undeniable sign of good management. As an Essentials publication, this book does not cover everything in depth, and it certainly won’t make you a strategy expert. But it does address all the important topics, and will get you off to a very good start—and with substantial confidence.

Strategy creation is about doing the right things and is a primary concern of senior executives and business owners. Implementation is about doing things right, a much different set of activities. Both senior executives and lower-ranking managers must give implementation intense attention, since even a great strategy is worthless if people fail to implement it properly. Yet, oddly, much has been written about business strategy but far less has been written about implementation. We hope to correct that problem in the chapters that follow.

What Is Strategy?

In its original sense, strategy (from the Greek word, strategos) is a military term used to describe the art of the general. It refers to the general’s plan for arraying and maneuvering his forces with the goal of defeating an enemy army. Carl von Clausewitz, the nineteenth-century theoretician of the art of war, described strategy as “concerned with drafting the plan of war and shaping the individual campaigns, and within these, deciding on the individual engagements.”1 More recently, in the era when nation states are pitted against each other, the concept of strategy has broadened. Historian Edward Mead Earle describes it as “the art of controlling and utilizing the resources of a nation—or a coalition of nations—including its armed forces, to the end that its vital interests shall be effectively promoted and secured.”2

Businesspeople have always liked military analogies, so it is not surprising that they have embraced the notion of strategy. They too began to think of strategy as a plan for controlling and utilizing their resources (human, physical, and financial) with the goal of promoting and securing their vital interests. Kenneth Andrews was the first to articulate these emerging ideas in his classic, The Concept of Corporate Strategy, published in 1971. Andrews described a framework that remains useful today, defining strategy in terms of what a business can do—that is, its strengths and weaknesses—and what possibilities are open to it—that is, the outer environment of opportunities and threats.3 A decade or so later, Harvard professor Michael Porter sharpened this definition, describing strategy as “a broad formula for how a business is going to compete.”4

Bruce Henderson, founder of The Boston Consulting Group, and one of the tribal elders of corporate strategy, connected the notion of strategy with competitive advantage, perhaps borrowing a concept drawn from economics (comparative advantage). A competitive advantage is a function of strategy that puts a firm in a better position than rivals to create economic value for customers. Henderson wrote that “Strategy is a deliberate search for a plan of action that will develop a business’s competitive advantage and compound it.” Competitive advantage, he went on, is founded in differences. “The differences between you and your competitors are the basis of your advantage.”5

Henderson believes that no two competitors could coexist if both sought to do business in the same way. They must differentiate themselves to survive. “Each must be different enough to have a unique advantage.” For example, two men’s clothing stores on the same block—one featuring formal attire and the other focusing on leisure wear—could potentially survive and prosper. Their physical proximity might even create mutual benefits. However, if the same two stores were to sell the same things under the same terms, one or the other would perish. Faced with this situation, each would attempt to differentiate itself in ways most pleasing to customers—through price, product mix, or ambiance.

Michael Porter concurs with Henderson’s idea of being different: “Competitive strategy is about being different. It means deliberately choosing a different set of activities to deliver a unique mix of value.”6 Consider these familiar examples:

- Southwest Airlines didn’t become the most profitable air carrier in North America by copying its rivals. It differentiated itself with a strategy characterized by low fares, frequent departures, point-to-point service, and customer-pleasing service.

- eBay created a different way for people to sell and acquire goods: online auctions. Company founders aimed to serve the same purpose as classified ads, flea markets, and formal auctions, but made it simple, efficient, and wide-reaching. Online auctions have differentiated the company’s service from those of traditional competitors.

- Toyota’s strategy in developing the hybrid engine Prius passenger car was to create a competitive advantage in the eyes of an important segment of auto buyers: people who want a vehicle that is environmentally benign, cheap to operate, and/or the latest thing in auto engineering.

So far, these strategies have served their initiators very well and have provided competitive advantages over rivals. Southwest is the most profitable U.S. air carrier, eBay is the most successful Internet company ever, and, at this writing, Toyota has a four-month waiting list of customers for its hybrid car. Being different can take many forms. As we’ll see later, even companies whose products are identical to their competitors’ can strategically set themselves apart by, for example, offering a better price or by providing faster and more reliable delivery.

Being “different,” of course, does not in itself confer competitive advantage or assure business success. A rocket car would be “different” but would be unlikely to attract enough customers to be successful. A hybrid (gasoline/electric) powered car, in contrast, is different in a way that creates superior value for customers in terms of fuel economy and low exhaust emissions. Those are values for which customers will gladly pay.

So, what is strategy? Strategy is a plan that aims to give the enterprise a competitive advantage over rivals through differentiation. Strategy is about understanding what you do, what you want to become, and—most importantly—focusing on how you plan to get there. Likewise, it is about what you don’t do; it draws boundaries around the scope of a company’s intentions. A sound strategy, skillfully implemented, identifies the goals and direction that managers and employees at every level need in order to define their work and make their organization successful. An organization without a clear strategy, in contrast, is rudderless. It flails about, dashing off in one direction after another as opportunities present themselves, but never achieving a great deal.

Strategy operates at both corporate and operating unit levels. For example, General Electric consists of many divisions operating in different industries: aircraft engines, home appliances, capital services, lighting, medical systems, plastics, power systems, and electrical distribution and control. It even owns NBC, one of the major U.S. television networks. The people who run this vast enterprise have a strategy, as do the senior managers of each division. Because the divisions operate in very different industries and competitive environments, their strategies must, of necessity, be unique. But each must be aligned with the larger corporate strategy.

Strategy Versus Business Model

Many confuse strategy with a newly popular term: business model. That expression first came into popular use in the late 1980s, at a time when people were gaining experience with personal computers and spreadsheet software. Thanks to these software innovations, businesspeople found that they could easily “model” the costs and revenues associated with any proposed business. After the model was set up, it took only a few keystrokes to observe the impact of individual changes—for example, in unit price, profit margin, and supplier costs—on the bottom line. Pro forma financial statements were the primary documents of business modeling. By the time dot-com fever had become rampant, the term was a popular buzzword. Still, most people were unable to articulate exactly what it meant.

Scholars define a business model as the economic underpinnings of an enterprise’s strategy. Management consultant Joan Magretta has provided a useful introduction to business models in “Why Business Models Matter,” a 2002 Harvard Business Review article in which she describes a business model as some variation of the value chain that supports every business. “Broadly speaking,” she writes, “this chain has two parts. Part one includes all the activities associated with making something: designing it, purchasing raw materials, manufacturing, and so on. Part two includes all the activities associated with selling something: finding and reaching customers, transacting a sale, distributing the product or delivering the service.”7 Thus, the business model is more about the mechanisms through which the entity produces and delivers a product or service, and less about what differentiates it in the eyes of customers and gives it competitive advantage. It answers these questions: How does this thing work? What underlying economic logic explains how we can deliver value to customers at an appropriate cost?

Every viable organization is built on a sound business model, but a business model isn’t a strategy, even though many people use the terms interchangeably. Business models describe, as a system, how the pieces of a business fit together to produce a profit. But they don’t factor in a critical dimension of performance: competition. That’s the job of strategy.

Some of today’s most powerful and profitable companies grew out of business models that were elegant and compelling in their logic and powerful in economic potential. Dell Computer is one of these and the most often-cited example. eBay, the online auction company, is another such example. It grew out of a very simple and traditional model. Like a long-distance telephone company, eBay created an infrastructure that allowed people to communicate; and, again like the long-distance provider, it picked up a modest fee from each use. Its Web-based infrastructure of software, servers, and rules of behavior allows a community of buyers and sellers to meet and conduct transactions for all manner of goods—from Elvis memorabilia to used Porsches. The company takes no part in the transactions, thereby avoiding many of the costs incurred by other businesses. Its only responsibilities are to maintain the integrity of the auction process and the information system that make its auctions possible.

As a mechanism for generating income, the eBay model is simple. It receives revenues from seller fees. Those revenues are reduced by the cost of building and maintaining the online infrastructure and by the usual marketing, product development, general, and administrative costs that keep the operation running and that attract buyers and sellers to the site. The net of these revenues and costs is profits for eBay shareholders.

Aside from its simplicity, the great power of the eBay model is the fact that a small number of salaried employees and outsource partners can handle a huge and growing volume of business. Further, a doubling of transaction volume (and revenue) can be accommodated with relatively modest investments. Software and servers do the heavy lifting. This activity is much different from the company’s stated strategy, which is to build and effectively support the world’s most efficient and abundant Web-based marketplace—a marketplace in which anyone, anywhere, can buy or sell almost anything.

As this example should make clear, strategy and business models are different concepts, even though they are related. While strategy provides differentiation and competitive advantage, the business model explains the economics of how the business works and makes money.

The Strategy Process

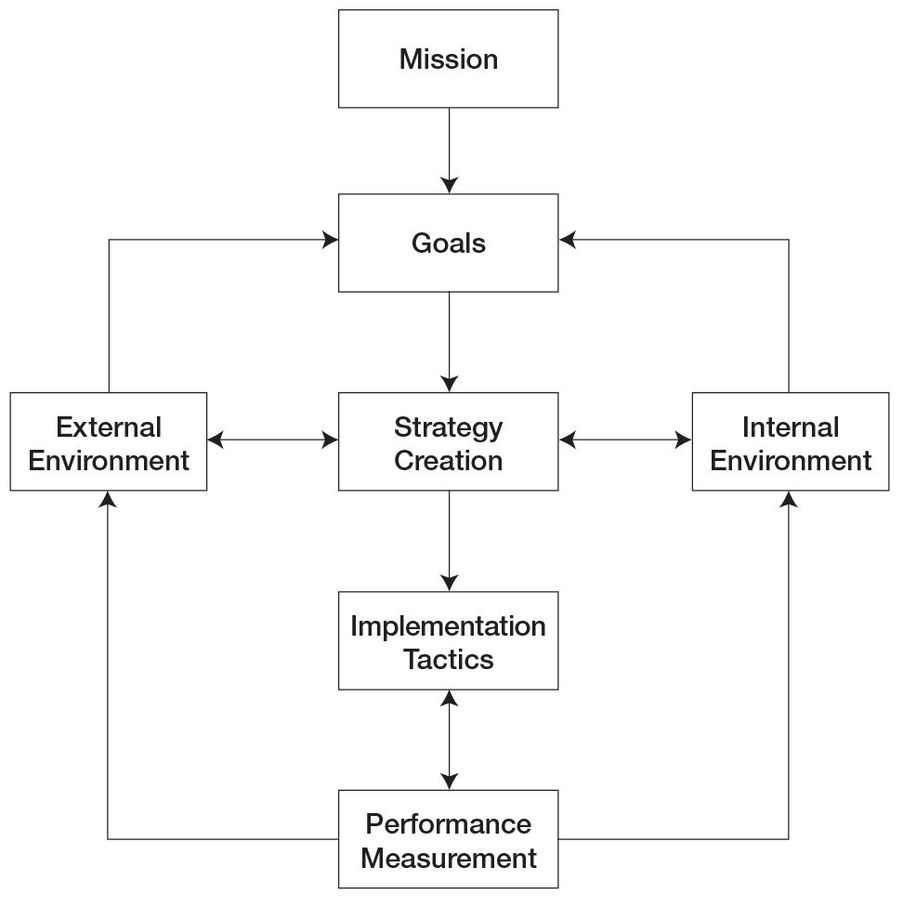

Like most important things in business, strategy creation and its implementation should be approached as a process, that is, as a set of activities that transforms inputs into outputs. This process is described graphically in figure I-1. Here we see that strategy creation follows from the mission of the company, which defines its purpose and what it aims to do for customers and other stakeholders. Given the mission, senior management sets goals—tangible manifestations of the organization’s mission that are used to measure progress. Goals, as shown in the figure, should be informed by a pragmatic understanding of both the external business/market environment and the internal capabilities of the organization.

Strategy creation typically begins with extensive research and analysis and a process through which senior management zeros in on the top priority issues that the company needs to tackle to be successful in the long term. For each priority issue, units and teams are asked to create high-level action plans. Once these action plans are developed, the company’s high-level strategic objectives and direction statement are further clarified.

The Strategy Process

Strategic creation takes time and requires a series of back-andforth communications between senior management and operating units, whereby all parties examine, discuss, and refine the plan. As a result, various planning streams often happen in parallel. The importance of involvement of operating units in the strategic planning processes cannot be overemphasized. Operating units house tremendous knowledge about their own capabilities and the competitive environments in which they operate. People in the operating units can make informed recommendations about what the company should be doing and where it should be going. Furthermore, units that are included in the planning process are more likely to support and implement the plans that are created. Units are the implementation centers of an organization. They have the leadership, people, and skills needed for effective execution. Organizations that fail to include units in the strategic planning process typically receive results inferior to those that do.

By undertaking the planning process together, senior management and unit leaders ensure that a company’s strategies—corporate and unit—are tightly aligned and that successful implementation can follow.

What’s Ahead

Strategy begins with goals, which follow naturally from the entity’s mission. Goals, in turn, are influenced by an iterative sensing of the external environment and the organization’s internal capabilities. The strategic choices available to a company likewise emerge from the process of looking outside and inside. Strategic planners refer to this activity as SWOT analysis: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. Chapter 1 will help you examine the external environment of opportunities and threats. Chapter 2 turns the focus inward, to the strengths and weaknesses of the enterprise. Knowledge of this inner world imparts a practical sense about what company goals and what strategies are most feasible and promising. The chapter’s emphasis is on the most important areas in which a company’s strengths and weaknesses should be evaluated: core competencies and processes, financial condition, and management and culture.

Once you’ve gotten a clear sense of your company’s strengths and weaknesses and the external environment in which you must operate, the question is, “What type of strategy should we pursue?” There are many strategy “types” from which to choose. Chapter 3 describes four generic types and what it takes to succeed with each: low-cost leadership, product/service differentiation, customer relationship, and network effect. Chances are that one of these—or some variation thereof—will be appropriate for your company and give it a defensible and profitable hold on some segment of the market.

Chapter 4 continues the discussion, indicating how strategy can be used to enter and build defensible positions in the marketplace. It explores a number of potential strategic moves: creating a market beachhead, using innovation to overcome barriers to entry, the principles of judo strategy, and others.

Having a great strategy is only part of the challenge. Equal or greater attention must be given to implementation, the many measures that translate strategic intent into actions that produce results. Chapter 5 takes us from strategy creation to the first steps of strategy implementation. It explains the need for alignment between strategy and the day-to-day details of how your company operates. Successful alignment and implementation begins with action plans developed and executed at the unit level. Chapter 6 segments the action-planning process into a number of key steps. It also contains an example of one company’s formal action plan.

Chapter 7 is about keeping action plans on track. Managers cannot simply issue a set of instructions and expect flawless implementation. Instead, they must support their plans with consistent behaviors, training, and other reinforcing. And they must communicate relentlessly with respect to the nature of the strategy and its benefits to everyone in the company.

People are the most important part of implementation. Harnessing their energy and commitment to strategic change is often management’s greatest challenge. Employees must feel that they’ve had something to say about the plans they are told to implement. They must know that success is important to their personal careers and fortunes. They must be motivated to do the right things well. And they must see real incentives for all their hard work. Chapter 8 addresses each of these requirements.

No strategy, even a great one, remains effective forever. Something in the environment eventually changes, rendering the current strategy ineffective or unprofitable. Leaders must be alert to these changes. Chapter 9 explains how managers can assess the effectiveness of their current strategies and recognize when they are losing the power to capture and satisfy customers. It offers tips on how they can monitor the performance of their strategies and identify areas where their intervention is necessary.

That’s it for the book’s chapters. But the end matter contains material you may also find useful. First, there is an appendix, which contains the following items:

- Worksheet for Conducting a SWOT Analysis. SWOT analysis, as described in chapters 1 and 2, is used by strategic planners to identify the company’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. This worksheet can help you to be systematic in thinking about and evaluating these internal and external factors. Free copies of this worksheet can be downloaded from the Harvard Business Essentials series Web site: www.elearning.hbsp.org/businesstools. You’ll also find other useful management and financial tools on that site.

- Worksheet for Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). Work breakdown structure, borrowed from the art and science of project management, is one of the implementation tools described in the text. You can use this worksheet to deconstruct large tasks into their component parts and to estimate the time needed to complete them. This worksheet is also downloadable from the series Web site.

- Project Progress Report. If you treat your strategy implementation as a project, you’ll find this a useful tool for noting progress to key milestones, key decisions, and budget status. It is downloadable from the series Web site.

The worksheet appendix is followed by a glossary of terms particular to strategy creation and implementation. Every business activity has its specialized vocabulary, and this one is no different. When you see a term in italics, that’s your cue that it’s included in the glossary.

A final section identifies readily available books and articles that can tell you more about topics covered in this book. Being an Essentials book, this volume cannot cover everything you might want to know about strategy creation and implementation, so if you want to know more, refer to the publications listed in this section.

The content of this book draws heavily on the strategy scholarship published in books and articles over the past twenty-four years. Many of these first appeared as articles in the Harvard Business Review. For material on strategy implementation, some of the best material was found in Harvard ManageMentor® on Implementing Strategy, an online service of Harvard Business School Publishing. All other sources are noted with standard endnote citations.