Developing a Vision and Strategy

Imagine the following. Three groups of ten individuals are in a park at lunchtime with a rainstorm threatening. In the first group, someone says: “Get up and follow me.” When he starts walking and only a few others join in, he yells to those still seated: “Up, I said, and now!” In the second group, someone says: “We’re going to have to move. Here’s the plan. Each of us stands up and marches in the direction of the apple tree. Please stay at least two feet away from other group members and do not run. Do not leave any personal belongings on the ground here and be sure to stop at the base of the tree. When we are all there . . .” In the third group, someone tells the others: “It’s going to rain in a few minutes. Why don’t we go over there and sit under that huge apple tree. We’ll stay dry, and we can have fresh apples for lunch.”

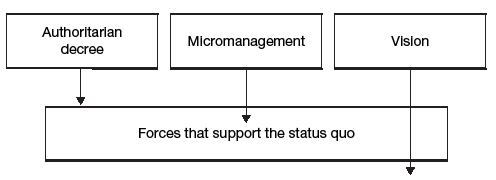

I am sometimes amazed at how many people try to transform organizations using methods that look like the first two scenarios: authoritarian decree and micromanagement. Both approaches have been applied widely in enterprises over the last century, but mostly for maintaining existing systems, not transforming those systems into something better. When the goal is behavior change, unless the boss is extremely powerful, authoritarian decree often works poorly even in simple situations, like the apple tree case. Increasingly, in complex organizations, this approach doesn’t work at all. Without the power of kings and queens behind it, authoritarianism is unlikely to break through all the forces of resistance. People will ignore you or pretend to cooperate while doing everything possible to undermine your efforts. Micromanagement tries to get around this problem by specifying what employees should do in detail and then monitoring compliance. This tactic can break through some of the barriers to change, but in an increasingly unacceptable amount of time. Because the creation and communication of detailed plans is deadly slow, the change produced this way tends to be highly incremental. Only the approach used in the third scenario above has the potential to break through all the forces that support the status quo and to encourage the kind of dramatic shifts found in successful transformations. (See figure 5–1.) This approach is based on vision—a central component of all great leadership.

FIGURE 5-1

Breaking through resistance with vision

Why Vision Is Essential

Vision refers to a picture of the future with some implicit or explicit commentary on why people should strive to create that future. In a change process, a good vision serves three important purposes. First, by clarifying the general direction for change, by saying the corporate equivalent of “we need to be south of here in a few years instead of where we are today,” it simplifies hundreds or thousands of more detailed decisions. Second, it motivates people to take action in the right direction, even if the initial steps are personally painful. Third, it helps coordinate the actions of different people, even thousands and thousands of individuals, in a remarkably fast and efficient way.

Clarifying the direction of change is important because, more often than not, people disagree on direction, or are confused, or wonder whether significant change is really necessary. An effective vision and back-up strategies help resolve these issues. They say: This is how our world is changing, and here are compelling reasons why we should set these goals and pursue these new products (or acquisitions or quality programs) to accomplish the goals. With clarity of direction, the inability to make decisions can disappear. Endless debates about whether to buy this company or to use the money to hire more sales reps, about whether a reorganization is really needed, or about whether international expansion is moving fast enough often evaporate. One simple question—is this in line with the vision?—can help eliminate hours, days, or even months of torturous discussion.

In a similar way, a good vision can help clear the decks of expensive and time-consuming clutter. With clarity of direction, inappropriate projects can be identified and terminated, even if they have political support. The resources thus freed can be put toward the transformation process.

A second essential function vision serves is to facilitate major changes by motivating action that is not necessarily in people’s short-term self-interests. The alterations called for in a sensible vision almost always involve some pain. Occasionally, the price of a better future is small; in the apple tree example, all people had to do was sacrifice their comfort for a minute while they walked over to the tree. But in many organizations, employees are increasingly forced out of their comfort zones, made to work with fewer resources, asked to learn new skills and behaviors, and threatened with the possibility of job loss. Under these circumstances, no one should be surprised that a rational human being might view all this without much enthusiasm. A good vision helps to overcome this natural reluctance to do what is (often painfully) necessary by being hopeful and therefore motivating. A good vision acknowledges that sacrifices will be necessary but makes clear that these sacrifices will yield particular benefits and personal satisfactions that are far superior to those available today—or tomorrow—without attempting to change.

Even in situations that require significant downsizing, where the natural inclination is to want to deny the future because it is depressing and demoralizing, the right vision can give people an appealing cause for which to fight. Thus: Our present course will lead us to bankruptcy, but if we go this way we can save some jobs, or prevent problems for our many customers and suppliers, or help the thousands of middle-class families that have invested through their pension funds or other savings in the firm.

Third, vision helps align individuals, thus coordinating the actions of motivated people in a remarkably efficient way. The alternatives—a zillion detailed directives or endless meetings—are much slower and costlier. With clarity of vision, managers and employees can figure out for themselves what to do without constantly checking with a boss or their peers.

This third feature of vision is often enormously important. The coordination costs of change, especially when many people are involved, can be gargantuan. Without a shared sense of direction, interdependent people can end up in constant conflict and nonstop meetings. With a shared vision, they can work with some degree of autonomy and yet not trip over each other.

The Nature of an Effective Vision

The word vision connotates something grand or mystical, but the direction that guides successful transformations is often simple and mundane, as in: “It’s going to pour, let’s go under that apple tree for shelter and eat some of the fruit for lunch.”

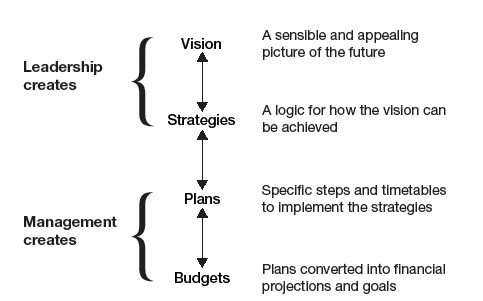

A vision can be mundane and simple, at least partially, because in successful transformations it is only one element in a larger system that also includes strategies, plans, and budgets (see figure 5–2). But although it is only one factor in a large system, it is an especially important factor. Without vision, strategy making can be a much more contentious activity and budgeting can dissolve into a mindless exercise of taking last year’s numbers and changing them 5 percent one way or the other. Even more so, without a good vision, a clever strategy or a logical plan can rarely inspire the kind of action needed to produce major change.

FIGURE 5-2

The relationship of vision, strategies, plans, and budgets

TABLE 5-1

Characteristics of an effective vision

| • | Imaginable: Conveys a picture of what the future will look like |

| • | Desirable: Appeals to the long-term interests of employees, customers, stockholders, and others who have a stake in the enterprise |

| • | Feasible: Comprises realistic, attainable goals |

| • | Focused: Is clear enough to provide guidance in decision making |

| • | Flexible: Is general enough to allow individual initiative and alternative responses in light of changing conditions |

| • | Communicable: Is easy to communicate; can be successfully explained within five minutes |

Whether mundane sounding or not, effective visions seem to have at least six key characteristics (which are summarized in table 5–1). First, they describe some activity or organization as it will be in the future, often the distant future. Second, they articulate a set of possibilities that is in the best interests of most people who have a stake in the situation: customers, stockholders, employees. In contrast, poor visions, when followed, tend to ignore the legitimate interests of some groups. Third, effective visions are realistic. They aren’t pleasant fantasies that have no chance of realization. Ineffective visions often have a pie-in-the-sky quality. Good visions are also clear enough to motivate action but flexible enough to allow initiative. Bad visions are sometimes too vague, sometimes too specific. Finally, effective visions are easy to communicate. Ineffective visions can be impenetrable.

An Imaginable Picture of the Future

What would you think if you saw the following in the company newspaper: “Our vision is to become a firm that pays the very lowest wages possible, charges the highest prices the market will bear, and divides the spoils between stockholders and senior executives, mostly the latter.” Stated this bluntly, the message sounds outrageous, yet it is not far from the transformational vision that guides some companies today. Although the cynic in all of us would like us to believe that these firms are doing very well, the truth is that they rarely succeed except for short periods of time, if even that.

Reengineering, restructuring, and other change programs never work well over the long run unless they are guided by visions that appeal to most of the people who have a stake in the enterprise: employees, customers, stockholders, suppliers, communities. A good vision can demand sacrifices from some or all of these groups in order to produce a better future, but it never ignores the legitimate long-term interests of anyone. Visions that try to help some constituencies by trampling on the rights of others tend to be associated with the most nefarious of demigods. Although these kinds of visions can succeed for a while, especially in the hands of a charismatic leader, they ultimately demoralize followers, and they always motivate a counterattack. In business today, these counterattacks come from big institutional stockholders who pressure senior management in a number of ways, from customers who stop buying or join legal suits, and from employees who kill change through passive resistance.

Corporate visions that aren’t deeply rooted in the reality of product or service markets are increasingly recipes for disaster. Given a choice—and in most industries today buyers have choices—customers rarely tolerate producers that are not focused on their interests. The same is true in financial or labor markets. If employees or investors have alternatives, the organization that ignores their needs pursues a self-destructive path.

Why would an intelligent group of people pursue a vision that ignores the needs of customers, employees, or investors? From what I’ve observed, this normally happens when management is feeling pressure from one constituency at the same time that it has a quasi-monopoly position over another constituency. For example: When a strong labor union demands high wages and benefits, a weary management copes by passing all the costs on to customers who have few or no alternatives. Or the reverse: When customers with increasing alternatives from around the world demand better and cheaper products, a beleaguered management copes by squeezing salary and benefits out of weak employee groups. Short-term pressures and the human capacity to rationalize unwise or negative actions can combine to lead reasonable people to act in unreasonable ways.

Asking the following kinds of basic questions can help determine the desirability of a vision for change.

1. If the vision is made real, how will it affect customers? For those who are satisfied today, will this keep them satisfied? For those who are not entirely happy today, will this make them happier? For people who don’t buy from us now, will this attract them? In a few years, will we be doing a better job than the competition of offering increasingly superior products and services that serve real customer needs?

2. How will this vision affect stockholders? Will it keep them satisfied? If they are not entirely happy today, will this improve matters? If we are successful in implementing this change, are we likely to provide better financial returns than if we do otherwise?

3. How will this vision affect employees? If they are satisfied today, will this keep them happy? If they are disgruntled, will this help capture their hearts and minds? If we are successful, will we be able to offer better employment opportunities than those firms with whom we compete in labor markets?

Much has been written in the last decade about “balancing” the interests of stakeholders. That’s not what I’m talking about here. A vision that balances interests perfectly by promising to provide merely average benefits to customers, employees, and stockholders will not generate the support that is needed to accomplish major change. In competitive customer, financial, and labor markets, more is required. Everyone needs to be served well. Increasingly, the relevant question is not “do we cut costs or improve the product?” but “how do we both reduce our expenses and increase product quality?” Not “do we build a highly skilled and well-paid workforce or become the low-cost producer?” but “how do we create a top-of-the-line workforce that can make us the low-cost producer?”

RETORT: But that’s very difficult!

RESPONSE: You bet! And being able to deal with that challenge is more and more what separates winners from losers.

Strategic Feasibility

One sometimes sees corporate visions these days that promise the world but don’t provide a clue as to how or why a transformation is feasible. We will go from the lowest in productivity in our industry to the head of the pack. Terrific, but how? We will change from being a middle-of-the-road company to being the customer’s preferred choice. Wonderful, but how?

A vision with feasibility is more than a pipe dream. An effective description of the future involves stretching resources and capabilities. A vision that requires only a 3 percent improvement per year will never force the fundamental rethinking and change that are so often needed in rapidly shifting environments. But if transformation goals seem impossible, they will lack credibility and thus fail to motivate action. How much of a stretch will seem feasible is to a great degree a function of the communication process. Great leaders know how to make ambitious goals look doable—and I’ll have more to say about that in the next chapter.

Feasibility also means that a vision is grounded in a clear and rational understanding of the organization, its market environment, and competitive trends. This is where strategy plays an important role. Strategy provides both a logic and a first level of detail to show how a vision can be accomplished. For example, because the single biggest trend today is toward faster-moving and more competitive market environments, many firms need to become less inwardly focused, centralized, hierarchical, slow in decision making, and political if they are to succeed in the marketplace, provide superior financial returns, etc. An effective vision and the strategies that back it up must rationally address these realities.

An entire industry has blossomed, mostly in the last two decades, to help organizations with these issues. Strategy consultants gather all kinds of data, especially about markets and competition, and assist firms in making fundamental choices about what products to manufacture and how best to produce those offerings. The huge growth in this kind of consulting business says something significant about the difficulty organizations have in abandoning historical biases, developing new strategies, and assessing their feasibility.

Focus, Flexibility, and Ease of Communication

Effective visions are always focused enough to guide employees—to convey which actions are important and which are out of bounds. Statements of direction so vague that people can’t relate to them are not helpful. Thus, “To be a great company” does not express a very good vision, nor does the slightly more specific “To become the best firm in the telecommunications industry.” In both cases, the question left unanswered is “best at what?” Having the best cafeteria food? The best parking lots?

Of course, people sometimes go too far in trying to be clear. Effective visions are open ended enough to allow for individual initiative and for changing conditions. Long and detailed pronouncements not only can feel like straitjackets but can soon become obsolete in a rapidly changing world. At the same time, visions that need constant readjustments lose their credibility.

Between the two extremes of impossibly vague and meticulously detailed is a lot of room. In selecting where to operate, executives guiding successful transformations often choose communicability as a key criterion. Even a desirable, focused, and feasible description of the future is useless if it is so complex that communicating it to large numbers of people is impossible. The point here is not to take a good idea and “dumb it down.” But as we will see in the next chapter, communicating even a simple vision to a large number of people can be enormously difficult. Simplicity is essential.

Effective and Ineffective Visions: A Few Examples

In some ways, it’s easier to describe visions that don’t help produce needed change than those that do. For example:

1. “Fifteen percent earnings per share growth” is not an effective vision. As I’ve seen in a number of companies, such a financial goal will not feel desirable to some, may not seem feasible to others, and offers few clues as to what actions are needed to achieve it.

2. An effective vision is not a four-inch-thick notebook describing the “Quality Program.” After reading 800 pages, most people tend to become depressed instead of motivated.

3. An effective vision is not a hopelessly vague listing of positive values (“We stand for integrity, safe products, a clean environment, good employee relations, etc.”). Such lists never provide clear direction and turn off everyone but extreme idealists.

So what is an effective vision? The management in one U.S. insurance company believes the following is helping to transform the firm:

It is our goal to become the world leader in our industry within ten years. As we use this term, leadership means more revenue, more profit, more innovation that serves our customers’ needs, and a more attractive place to work than any other competitor. Achieving this ambitious objective will probably require double-digit revenue and profit growth each year. It will surely require that we become less U.S. oriented, more externally focused, considerably less bureaucratic, and more of a service instead of a product company. We sincerely believe that if we work together we can achieve this change, and in the process create a firm that will be admired by our stockholders, customers, employees, and communities.

Statements as brief as this one are sometimes nothing but meaningless happy talk. But read the above paragraph again and you will see that it contains a lot of information. While the statement does not give anything close to a detailed directive, it does provide focus by (1) eliminating many possibilities (for example, becoming a conglomerate, remaining strictly a U.S.-based company, exploiting the workforce), (2) pointing specifically to areas that need to change (for example, from a product orientation to a service culture), and (3) stating a clear target (number one in the industry in ten years). There is an explicit statement about desirability (“admired by stockholders . . .”). And it is reasonably easy to communicate (only a hundred or so words).

An expanded version of this short statement fills three pages and more directly addresses the feasibility issue with a discussion of strategy. But even the content of the three-page document can be conveyed within five minutes. Remember my rule of thumb: If you cannot describe your vision to someone in five minutes and get their interest, you have more work to do in this phase of a transformation process.

Here’s another example, this one more narrowly focused on a particular project:

The vision driving our department’s reengineering effort is simple. We want to reduce our costs by at least 30 percent and increase the speed with which we can respond to customers by at least 40 percent. These are stretch goals, but we know based on the pilot project in Austin that they are achievable if we all work together. When this is completed, in approximately three years, we will have leapfrogged our biggest competitors and achieved all the associated benefits: better satisfied customers, increased revenue growth, more job security, and the enormous pride that comes from great accomplishments.

Like these two examples, the most effective transformational visions I’ve seen in the past few years all seem to share the following characteristics:

1. They are ambitious enough to force people out of comfortable routines. Becoming 5 percent better is not the goal; becoming the best at something is often the goal.

2. They aim in a general way at providing better and better products or services at lower and lower costs, thus appealing greatly to customers and stockholders.

3. They take advantage of fundamental trends, especially globalization and new technology.

4. They make no attempt to exploit anyone and thus have a certain moral power.

Creating the Vision

Over the past decade, I’ve closely observed a dozen companies as they tried to create effective visions for change. From that experience, I conclude the following: developing a good vision is an exercise of both the head and the heart, it takes some time, it always involves a group of people, and it is tough to do well.

The first draft often comes from a single individual. Such a person draws on his or her experiences and values to create a set of ideas that both makes sense and is personally exciting. In successful transformations, these ideas are then discussed at length with the guiding coalition. The discussion almost always modifies the original ideas by eliminating one element, adding others, and/or clarifying the statement. I have seen some people try to accomplish this in a process that is as disciplined as the formal planning system, but that never seems to work well. Vision creation is almost always a messy, difficult, and sometimes emotionally charged exercise.

In one typical case, the head of a medium-size retail business had his human resources and strategic planning vice presidents draft a statement based on his ideas. That document became the focus of attention at a stressful two-day off-site management meeting. Halfway through that session, despite a beautiful and sunny resort setting, most of the attendees probably wished they were back home in two feet of snow. The boss may even have felt that way himself. The problem was that the draft vision statement brought to the surface a number of conflicting worldviews held by members of the executive committee. It also made one person extremely anxious, because it spoke of a future in which his group would become less important. And for at least two of the attendees, maybe more, the process was too fuzzy and soft. Today, I think almost all the senior managers at this company would agree on the value of that meeting and subsequent discussions. But at the time, the session was not much fun.

Instead of backing down when the conflicts emerged, the boss gently but firmly pushed ahead. He used his not inconsiderable interpersonal skills to keep the pressure at a tolerable level. If he had skipped the first two phases of the transformation process, the meeting might have blown up. But having developed a sense of urgency and established a healthy degree of trust and a shared commitment to excellence, the group was able to work its way through a difficult set of topics and tentatively agree on a modified version of the document.

With notes from that session and some additional staff work, the boss then drafted a second statement, which was discussed with his guiding coalition over a six-month period. He went public with a revised document after that and has added to or modified it slightly on two occasions over the past four years.

Vision creation can be difficult for at least five reasons (as summarized in table 5–2). First, we have raised a number of generations of very talented people to be managers, not leaders or leader/managers, and vision is not a component of effective management. The managerial equivalent to vision creation is planning. Ask a good manager what his or her vision is, and you’ll likely hear about the operating plan—for example, to introduce this product in June, to hire X new people by September, to make $Y after taxes this year. But a plan can never direct, align, and inspire action the way vision can, and it is therefore not sufficient during transformation. In a slower-moving past, we didn’t need to teach people much about this sort of activity, so we didn’t. Again, history is working against us.

TABLE 5-2

Creating an effective vision

| • | First draft: The process often starts with an initial statement from a single individual, reflecting both his or her dreams and real marketplace needs. |

| • | Role of the guiding coalition: The first draft is always modeled over time by the guiding coalition or an even larger group of people. |

| • | Importance of teamwork: The group process never works well without a minimum of effective teamwork. |

| • | Role of the head and the heart: Both analytical thinking and a lot of dreaming are essential throughout the activity. |

| • | Messiness of the process: Vision creation is usually a process of two steps forward and one back, movement to the left and then to the right. |

| • | Time frame: Vision is never created in a single meeting. The activity takes months, sometimes years. |

| • | End product: The process results in a direction for the future that is desirable, feasible, focused, flexible, and is conveyable in five minutes or less. |

Second, although a good vision has a certain elegant simplicity, the data and the syntheses required to produce it are usually anything but simple. A ten-foot stack of paperwork, reports, financials, and statistics are sometimes needed to help produce a one-page statement of future direction. And the analysis of all that information is not the sort of activity that can be delegated to a supercomputer.

Third, both head and heart are required in this exercise. After seventeen or more years of formal education, most of us know something about using our heads but little about using our hearts. Yet all effective visions seem to be grounded in sensible values as well as analytically sound thinking, and the values have to be ones that resonate deeply with the executives on the guiding coalition. As a result, creating a vision is not just a strategy exercise in assessing environmental opportunities and organizational capabilities. The process very much involves getting in touch with ourselves—who we are and what we care about. In a personal sense, the exercise can be quite rewarding. But for people who are not introspective or self-aware, this activity can also be difficult and anxiety producing.

Fourth, if teamwork does not exist in the guiding coalition, parochialism can turn vision creation into an endless negotiation. I once watched a frustrated group of executives in a computer company work for two years to try to get agreement on the basic elements of a transformational vision. The time spent in formal meetings and in more informal, one-on-one discussions added up to a staggering number of hours. Yet these executives never achieved their objective: the creation of a sensible vision to which they were committed. The biggest problem was that too few people were actually trying to achieve that goal. Instead, most were protecting their subgroup’s narrowly defined interests.

Finally, if the urgency rate is not high enough, you will never find enough time to complete the process. Meetings become hard to schedule. Work in between sessions moves slowly. Before you know it, a year has gone by and little has been accomplished. Pressures build to create something, so afar less than ideal product is accepted and you move on. Under these circumstances, the resulting vision is usually a small increment from the status quo or a bolder statement that most people on the guiding coalition don’t really believe. The fact that the vision isn’t quite right, or isn’t ambitious enough, or has limited support eventually undermines the change effort.

Because of the anxieties and conflicts attending vision creation, I often see people cutting the process off prematurely. Long before the members of the guiding coalition have had sufficient chance to think, feel, argue, and reflect, the vision is engraved on wall plaques or encased in clear plastic. When this happens, the transformation process is always hurt.

Remember: An ineffective vision may be worse than no vision at all. Pursuit of a poorly developed vision can sometimes send people off a cliff. And lip service without commitment creates a sort of dangerous illusion. People will think they are building on a solid base, only to find that the bottom of the structure eventually collapses, destroying all their work. In either case, once they learn of the problems caused by the premature shutting off of the vision creation process, employees can become deeply cynical about transformation. With deeply cynical people, you rarely achieve successful change.

I’ve said it before, but the idea deserves repeating. Whenever you leave one of the steps in the eight-stage change process without finishing the work, you usually pay a big price later on. Without a sufficiently strong foundation, the redirection collapses at some point, forcing you to go back and rebuild. For stage 3, creating a vision and strategy, this means taking the time to do the process correctly. Think of it as an investment, an important investment, in creating a better future.