CHAPTER FOUR

WHO ARE THE BEST CUSTOMERS

FOR OUR PRODUCTS?

Which customers should we target? Which customer base will be the most valuable foundation for future growth? Is our growth potential greatest if we pursue the largest markets? How can we predict which competitors will target which sets of customers? What sales and distribution channels will most capably embrace our product and devote the resources required to grow the market as fast as possible?

The message of chapter 2 was that although sustaining innovations are critical to the growth of existing businesses, a disruptive strategy offers a much higher probability of success in building new-growth businesses. chapter 3’s message was that managers often segment markets along the lines for which data are available, rather than in ways that reflect the things that customers are trying to get done. Using flawed segmentation schemes, they often introduce products that customers don’t want, because they aim at a target that is irrelevant to what customers are trying to get done. This chapter addresses two questions that are closely tied to the last: Which initial customers are most likely to become the solid foundation upon which we can build a successful growth business? And how should we reach them?

It’s relatively straightforward to find the ideal customers for a lowend disruption. They are current users of a mainstream product who seem disinterested in offers to sell them improved-performance products. They may be willing to accept improved products, but they are unwilling to pay premium prices to get them.1 The key to success with low-end disruptions is to devise a business model that can earn attractive returns at the discount prices required to win business at the low end.

It is much trickier to find the new-market customers (or “nonconsumers”) on the third axis of the disruptive innovation model. How can you know whether current nonconsumers can be enticed to begin consuming? When only a fraction of a population is using a product, of course, some of the nonconsumption may simply reflect the fact that there just isn’t a job needing to be done in the lives of those non-consumers. That is why the “jobs question” is a critical early test for a viable new-market disruption. A product that purports to help non-consumers do something that they weren’t already prioritizing in their lives is unlikely to succeed.

For example, throughout the 1990s a number of companies thought they saw a growth opportunity in the significant proportion of American households that did not yet own a computer. Reasoning that the cause of nonconsumption was that computers cost too much, they decided that they could create growth by developing an “appliance” that could access the Internet and perform the basic functions of a computer at a price around $200. A number of capable companies, including Oracle, tried to open this market, but failed. We suspect that there just weren’t any jobs needing to get done in those nonconsuming households for which less-expensive computers were a solution. chapter 3 taught us that circumstances like this are not good growth opportunities.

Another kind of nonconsumption occurs, however, when people are trying to get a job done but are unable to accomplish it themselves because the available products are too expensive or too complicated. Hence, they put up with getting it done in an inconvenient, expensive, or unsatisfying way. This type of nonconsumption is a growth opportunity. A new-market disruption is an innovation that enables a larger population of people who previously lacked the money or skill now to begin buying and using a product and doing the job for themselves. From this point onward, we will use the terms nonconsumers and nonconsumption to refer to this type of situation, where the job needs to get done but a good solution historically has been beyond reach. We sometimes say that innovators who target these new markets are competing against nonconsumption.

We’ll begin with three short case studies of new-market disruption, and then synthesize across these histories a common pattern that typifies the customers, applications, and channels where new-market disruptions tend to find their foothold. We’ll explore why so few companies historically have sought nonconsumers as the foundation for growth, and then close by suggesting what to do about it.

New-Market Disruptions: Three Case Histories

New-market disruptions follow a remarkably consistent pattern, regardless of the type of industry or the era in history when the disruption occurred. In this section we’ll synthesize this pattern from three disruptions: one from the 1950s, one that began in the 1980s and continues in the present, and a third that is still in its nascent stage. In these and scores of other cases we’ve studied, it is stunning to see the sins of the past so regularly visited upon the later generations of disruptees. Today we can see dozens of companies making the same predictable mistakes, and the disruptors capitalizing on them.

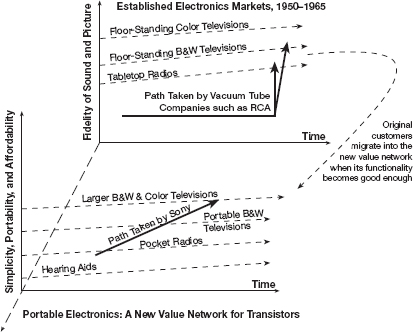

The Disruption of Vacuum Tubes by Transistors

Scientists at AT&T’s Bell Laboratories invented the transistor in 1947. It was disruptive relative to the prior technology, vacuum tubes. The early transistors could not handle the power required for the electronic products of the 1950s—tabletop radios, floor-standing televisions, early digital computers, and products for military and commercial telecommunications. As depicted in the original value network of figure 4-1, the vacuum tube makers, such as RCA, licensed the transistor from Bell Laboratories and brought it into their own laboratories, framing it as a technology problem. As a group they aggressively invested hundreds of millions of dollars trying to make solid-state technology good enough that it could be used in the market.

FIGURE 4 - 1

Value Networks for Vacuum Tubes and Transistors

While the vacuum tube makers worked feverishly in their laboratories targeting the existing market, the first application emerged in a new value network on the third axis of the disruption diagram: a germanium transistor hearing aid, an application that valued the low power consumption that made transistors worthless in the mainstream market. Then in 1955 Sony introduced the world’s first battery-powered, pocket transistor radio—an application that again valued transistors for attributes that were irrelevant in mainstream markets, such as low power consumption, ruggedness, and compactness.

Compared with the tabletop radios made by RCA, the sound from the Sony pocket radio was tinny and static-laced. But Sony thrived because it chose to compete against nonconsumption in a new value network. Rather than marketing its radio to consumers who owned tabletop devices, Sony instead targeted the rebar of humanity—teenagers, few of whom could afford big vacuum tube radios. The portable transistor radio offered them a rare treat: the chance to listen to rock and roll music with their friends in new places out of the earshot of their parents. The teenagers were thrilled to buy a product that wasn’t very good, because their alternative was no radio at all.

The next application emerged in 1959, with the introduction of Sony’s twelve-inch black-and-white portable television. Again, Sony’s strategy was to compete against nonconsumption, as it made televisions available to people who previously couldn’t afford them, many of whom lived in small apartments that lacked the space for floor-standing televisions. These customers were delighted to own products that weren’t nearly as good as the large TVs in the established market, because the alternative was no television at all.

As these major new disruptive markets for transistor-based products emerged, the traditional makers of vacuum tube–based appliances felt no pain because Sony wasn’t competing for their customers. Furthermore, the vacuum tube makers’ aggressive efforts to develop solid-state electronics in their own laboratories gave them comfort that they were doing what they should about the future.

When solid-state electronics finally became good enough to handle the power required in large televisions and radios, Sony and its retailers simply vacuumed out the customers from the original plane, as depicted in figure 4-1. Within a few years the vacuum tube–based companies, including the venerable RCA, had vaporized.

Targeting customers who had been nonconsumers worked magic for Sony in two ways. First, because its customers’ reference point was having no television or radio at all, they were delighted with simple, crummy products. The performance hurdle that Sony had to clear therefore was relatively easy. This entailed a much lower R&D investment prior to commercialization than the vacuum tube makers had to make to commercialize the identical technology. The established market presented a much higher performance barrier to surmount, because customers there would only embrace solid-state electronics when they became superior to vacuum tubes in those applications.2

Second, Sony’s sales grew to significant levels before RCA and its competitors felt any threat. The painlessness of Sony’s attack persisted even after its products improved to become performance-competitive with low-end vacuum tube–based products. When Sony started to pull the least-attractive customers from the original value network into its new one, losing those who bought their lowest-margin products actually felt good to makers of vacuum tube–based appliances. They were immersed in an aggressive up-market foray of their own into color television. These were large, complicated machines that sold for very attractive margins in their original value network. As a result, the vacuum tube companies’ profit margins actually improved as they were being disrupted. There simply was no crisis to prompt them to counterattack Sony.

When the crisis became clear, the manufacturers of vacuum tube products couldn’t just switch to the new technology and pull customers back into their old business model, because the cost structure of that model and of their distribution and sales channels was not competitive. The only way they could have retained or recaptured their customers would have been to reposition their companies in the new value network. That would have entailed, among other restructurings, shifting to a completely different channel of distribution.

Vacuum tube–based appliances were sold through appliance stores that made most of their profits replacing burned-out vacuum tubes in the products they had sold. Appliance stores couldn’t make money selling solid-state televisions and radios because they didn’t have vacuum tubes that would burn out. Sony and the other vendors of transistor-based products therefore had to create a new channel in their new value network. These were chain stores such as F. W. Woolworth and discount retailers such as Korvette’s and Kmart, which themselves had been “nonvendors”—they hadn’t been able to sell radios and televisions because they had lacked the ability to service burned-out vacuum tubes. When RCA and its vacuum tube cohort finally started making solid-state products and turned to the discount channel for distribution, they found that the shelf space had already been claimed.

The punishing thing about this outcome, of course, is that RCA and its colleagues didn’t fail because they didn’t invest aggressively in the new technology. They failed because they tried to cram the disruption into the largest and most obvious market, which was filled with customers whose business could only be won by selling them a product that was better in performance or cost than they already were using.

Angioplasty: A Disruption of Heart-Stopping Proportions

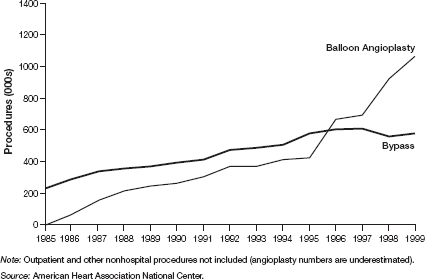

Balloon angioplasty is an ongoing example of a new-market disruption. Prior to the early 1980s, the only people with heart disease who could receive interventional therapy were those who were at high and immediate risk of death. There was a lot of nonconsumption in this market: Most people who suffered from heart disease simply went untreated. Angioplasty enabled a new group of providers—cardiologists—to treat coronary artery disease by threading a catheter into a partially clogged artery of these previously untreated patients and puffing up a balloon. It was often ineffective: Half of the patients suffered restenosis, or a reclogging of the artery, within a year. But because the procedure was simple and inexpensive, more patients with partially occluded arteries could begin receiving treatment. The cardiologists benefited too, because even without being trained in surgery they could keep the fees for themselves, and had to refer fewer patients to the heart surgeons, who earned the most handsome fees. Angioplasty thereby created a huge new growth market in cardiac care.

If its inventors had attempted to market angioplasty as a sustaining technology—a better alternative than cardiac bypass surgery—it would not have worked. Angioplasty couldn’t solve difficult blockage problems at the outset. Any attempt to improve it enough so that heart surgeons would choose angioplasty over bypass surgery would have entailed extraordinary time and expense.

Could the inventors have commercialized angioplasty as a lowend disruption—a less-expensive way for heart surgeons to treat their least-sick patients? No. Patients and surgeons weren’t yet overserved by the efficacy of bypass surgery.

The successful disruptive innovators chose a third approach: enabling less-seriously ill patients to receive therapy that was better than the alternative (nothing), and enabling cardiologists profitably to pull into their own practices patients who previously had to wait until they were sick enough to be referred to more expensive experts. Under these circumstances a booming new market emerged.

Figure 4-2 shows the growth that resulted from this disruption. Interestingly, for a very long time cardiac bypass surgery continued to grow, even as angioplasty began thriving and improving in its new value network. The reason was that in their efforts to treat patients with partially occluded arteries, cardiologists discovered many more patients whose arteries were too clogged to be opened with angioplasty—patients whose disease previously was not diagnosed. So heart surgeons felt no threat—in fact, they felt healthy, for a long time—just like the large steel mills and the makers of vacuum tubes.3

As cardiologists and their device suppliers pursued the higher profits that came from better products and premium services, they discovered that they could insert stents to prop open even difficult-to-open arteries. (Stents caused the up-kink in angioplasty growth that began in 1995.) Customers who otherwise would have needed bypass surgery are now being pulled into the new value network, and the cardiologists have done this without having to be trained as heart surgeons. This disruption has been underway for two decades, but the surgeons only recently have sensed the threat as the number of open-heart cardiac surgeries has begun to decline. In the most complex tiers of the market, there will be demand for open-heart surgery for a long time. But that market will shrink—and now that the disruption is apparent, there is little that the heart surgeons can do.

FIGURE 4 - 2

Number of Angioplasty and Cardiac Bypass Surgery Procedures

Like pocket radios and portable TVs, the “channels”—the venues in which interventional cardiac care is delivered—are also being disrupted. Bypass surgery is a hospital-based procedure because of the risks it entails. But little by little, as technology has improved cardiologists’ ability to diagnose and prevent complications, more and more angioplasty procedures are being performed in cardiac care clinics, whose costs make them disruptive relative to full-service hospitals.

Solar Versus Conventional Electrical Energy

Consider solar energy as a third example. It defies profitable commercialization despite billions of dollars invested to make the technology viable. This is indeed daunting when the business plan is to compete against conventional sources of electricity in developed countries. About two-thirds of the world’s population has access to electric power transmitted from central generating stations. In advanced economies this power is available almost all the time, is a very cost-effective means of getting work done, and is available essentially twenty-four hours per day, cloudy and sunny weather alike. This is a tough standard for solar energy to compete against.

Yet if developers of this technology instead targeted nonconsumers—the two billion people in South Asia and Africa who have no access to conventionally generated electricity—the prospects for solar energy might look quite different. The standard of comparison for those potential customers is no electricity at all. Their homes aren’t filled with power-hungry appliances, either, so it would be a vast improvement over the present state of affairs for these customers if they could store enough energy during daylight to power an electric light at night. Solar energy would be much less expensive, and would probably entail fewer headaches from governmental approvals and corruption, than would building a conventional generation and distribution infrastructure in those areas.

Some might protest that photovoltaic cells are simply too expensive ever to be made and sold profitably to impoverished populations. Maybe. But many of the technical paradigms in present photovoltaic technology were developed in attempts at sustaining innovation—to push the bleeding edge of performance as far as possible in the quest to compete against consumption in North America and Europe. Targeting new unserved markets would lower the performance hurdle, allowing some to conclude, for example, that instead of building the cells on silicon wafers they can deposit the required materials onto a sheet of plastic in a continuous, roll-to-roll process.

If history is any guide, the commercially viable innovations in clean energy will not come from government-financed research projects designed to make solar energy a preferred source of power in developed markets. Rather, the successful innovations will emerge from companies who carve disruptive footholds by targeting nonconsumption and moving up-market with better products only after they have started simple and small.

Extracting Growth from Nonconsumption: A Synthesis

We distill from these histories four elements of a pattern of new-market disruption. Managers can use this pattern as a template to find ideal customers and market applications for disruptive innovations, or they can use it to shape nascent ideas into business plans that match this proven pattern for generating new-market growth. These elements are as follows:

- The target customers are trying to get a job done, but because they lack the money or skill, a simple, inexpensive solution has been beyond reach.

- These customers will compare the disruptive product to having nothing at all. As a result, they are delighted to buy it even though it may not be as good as other products available at high prices to current users with deeper expertise in the original value network. The performance hurdle required to delight such new-market customers is quite modest.

- The technology that enables the disruption might be quite sophisticated, but disruptors deploy it to make the purchase and use of the product simple, convenient, and foolproof. It is the “foolproofedness” that creates new growth by enabling people with less money and training to begin consuming.

- The disruptive innovation creates a whole new value network. The new consumers typically purchase the product through new channels and use the product in new venues.

The history of each new-market disruptor in figure 2-4 mirrors this pattern. From Black & Decker to Intel, from Microsoft to Bloomberg, from Oracle to Cisco, from Toyota to Southwest Airlines, and from Intuit’s QuickBooks to Salesforce.com, new-market disruptions fit this pattern. In so doing, they have been a dominant engine of growth not just for shareholder value but for the world economy.

Disruptions that fit this pattern succeed because while all of this is happening, the established competitors view the entrants in the emerging market as irrelevant to their well-being.4 The growth in the new value network does not affect demand in the mainstream market for some time—in fact, incumbents sometimes prosper for a time because of the disruption. What is more, the incumbents are comfortable that they have sensed the threat and are responding. But it is the wrong response. They invest massive sums trying to advance the technology enough to please the customers in the existing value network. In so doing, they force the disruptive technology to compete on a sustaining basis—and nearly always, they fail.

It’s quite stunning, when you think about it. This pattern would strike most managers as a dream come true. What more could you want than a situation where customers are easily delighted, powerful competitors ignore you, and you’re locked arm-in-arm with channel partners in a win-win race toward exciting growth? We will explore next why this dream so often becomes a nightmare instead, and then suggest what to do about it.

What Makes Competing Against Nonconsumption So Hard?

The logic of competing against nonconsumption as the means for creating new-growth markets seems obvious. Despite this, established companies repeatedly do just the opposite. They choose to compete at the outset against consumption, trying to stretch the disruptive innovation to compete against—and ultimately supplant—established products, sold by well-entrenched competitors in large, obvious market applications. Doing this requires enormous amounts of money, and such attempts almost always fail. Established firms almost always do this, rather than shaping their ideas to fit the pattern of successful disruption noted earlier. Why?

In a very insightful stream of research, Harvard Business School Professor Clark Gilbert has helped us understand the fundamental mechanism that causes the established competitors in an industry to consistently cram the disruptive technology into the mainstream market. With that understanding, Gilbert also provides guidance to established company executives on how to avoid this trap, and capture the growth created by disruption instead.5

Threats Versus Opportunities

Gilbert has borrowed insights from the fields of cognitive and social psychology, as exemplified in the work of Nobel Prize winners Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, to study disruption.6 Kahneman and Tversky examined how individuals and groups perceive risk and noted that if you frame a phenomenon to an individual or a group as a threat, it elicits a far more intense and energetic response than if you frame the same phenomenon as an opportunity. Furthermore, other researchers have observed that when people encounter a significant threat, a response called “threat rigidity” sets in. The instinct of threat rigidity is to cease being flexible and to become “command and control” oriented—to focus everything on countering the threat in order to survive.7

You can see exactly this behavior among the established firms that experience new-market disruptions. Because the disruptions emerge at a time when the established firms’ core business is robust, framing the new-market disruption as an opportunity simply does not get people’s attention: It makes little sense to invest in new-growth businesses when the present ones are doing well.

When visionary executives and technologists do see the disruption coming, they frame it as a threat, seeing that their companies could be imperiled if these technologies succeed. This framing as a threat rather than an opportunity is what elicits a resource commitment from the established firms to address the technology. But because they instinctively define the disruption as a threat, they focus on being able to protect their customers and their current business. They want to be there with the new technology ready when they must switch to it in order to protect their current customers. This causes the organization to pursue a strategy that not only misses the growth opportunity but also leads to its eventual destruction—because the disruptors who take root in nonconsumption eventually kill them. This just means, however, that established firms must reposition themselves on the other side of the dilemma, at the appropriate time.

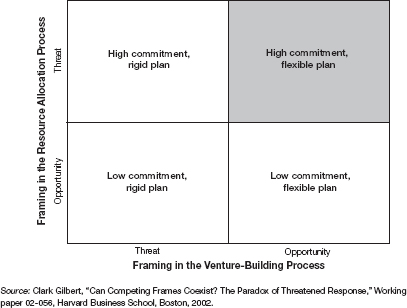

How to Get Commitment and Flexibility

Gilbert’s work, fortunately, not only defines an innovator’s dilemma but suggests a way out. The solution is twofold: First, get top-level commitment by framing an innovation as a threat during the resource allocation process. Later, shift responsibility for the project to an autonomous organization that can frame it as an opportunity.

In his study of how major metropolitan newspapers responded to the threat or opportunity of going online, Gilbert showed that in the initial period of threat framing, the project to address the disruption was always housed within the budgetary and strategic responsibility of the mainstream organization—because it had to be. In the case of newspapers, this entailed putting the newspaper online. The advertisers and readers of the online version were the same as those of the paper version. The newspapers did exactly what the vacuum tube and solar energy companies did: try to make the disruptive technology good enough that existing customers would use it instead of the existing physical newspaper.

At first blush, this market targeting seems senseless: Concerns about cannibalism become self-fulfilling prophecies. But threat framing makes sense of the paradox. Because current customers are the lifeblood of the company, they must be protected at all costs: “If the technology ever does in fact become good enough to begin to steal away our customers, we will be there with the new technology, ready to defend ourselves.”

In contrast to the dilemma facing the incumbents, threat framing isn’t a vexing issue for entrant firms. For them, the disruption is pure opportunity. This asymmetry of perceptions explains why incumbents so consistently try to cram the disruptive technology into mainstream markets, whereas the entrants pursue the new-market opportunity. Understanding this asymmetry, however, points to a solution. After senior managers have made a resolute commitment to address the disruption, responsibility to commercialize the disruption needs to be placed in an independent organizational unit for which the innovation represents pure opportunity.

This is what Gilbert noted in his newspaper study. After the initial period of threat framing that elicited resource commitment, Gilbert noted that a number of newspaper organizations spun off their online groups to become independently managed, stand-alone profit centers. When this happened, members of the newly independent groups switched their orientation, seeing themselves as involved in an opportunity with significant growth potential. When this happened, quite rapidly those organizations evolved significantly away from being just online replications of the newspaper. They implemented different services, found different suppliers, and earned their revenue from a different set of advertisers than the mainstream paper. Those newspapers that continued to house responsibility for their online effort within the mainstream news organization, in contrast, have continued on the self-destructive course of cannibalism, offering an online newspaper in defense of the core business.

Gilbert’s recommendations are summarized in figure 4-3. The disruption is best framed as a threat within the resource allocation process in order to garner adequate resources. But once the investment commitment has been made, those engaged in venture building must see only upside opportunity to create new growth. Otherwise, they will find themselves with a dangerous lack of flexibility or commitment.

An initial decision to fund a disruptive growth business is not the end of the resource allocation process or of the conflict between threat and opportunity framing. For several years in each annual budgeting cycle, the disruptive opportunity will seem insignificant. The way that many corporate entrepreneurs deal with these annual challenges to the value of new-growth ventures is by promising big numbers in the future in exchange for resources in the present. This is suicidal for two reasons. First, the biggest markets whose size can be substantiated are those that exist. The very effort to articulate a convincing case for resources actually forces the entrepreneurs to cram the innovation as a sustaining technology in the existing market. Second, if results fall short of projected numbers, senior managers often conclude that the potential market size is disappointingly small—and they cut resources as a result.

FIGURE 4 - 3

How to Garner Resource Commitments and Target Them at Disruptive Growth Opportunities

How do you deal with the rational need of the executives who manage resource allocation to focus investments where the risk/reward opportunity is most attractive? The answer is not to change the rules of evidence in the resource allocation process, because in successful companies, the well-honed operation of this process is critical to success on the sustaining trajectory. Decisions in that process can be rules based, because the environment is clear.

But companies that hope to create growth through new-market disruption need another, parallel process into which they can channel potentially disruptive opportunities. Ideas will enter this parallel process only partially formed. Those who manage this process then need to shape them into business plans that conform to the four elements of the pattern noted previously. Executives who allocate resources in this process should approve or kill project budgets based on fit with the pattern, not numerical rules. Fit constitutes a much more reliable predictor of success than do numbers in the uncertain environment of new-market disruption. If a project fits the pattern, executives can approve it with confidence that the initial conditions are conducive to successful growth.8 Ultimate success, of course, depends on aligning all the related actions and decisions that we discuss in later chapters.

Reaching New-Market Customers Often

Requires Disruptive Channels

In the final pages of this chapter, we hope to amplify the fourth element of the pattern of successful new-market disruption: going to market through a disruptive channel. The term channel as it is commonly used in business refers to the wholesale and retail companies that distribute and sell products. We assign a broader meaning to this word, however: A company’s channel includes not just wholesale distributors and retail stores, but any entity that adds value to or creates value around the company’s product as it wends its way toward the hands of the end user. For example, we will consider computer makers such as IBM and Compaq as the channels that Intel’s microprocessors and Microsoft’s operating system use to reach the end-use customer. A physician’s practice is the channel through which many health care products provide the needed care to patients. A company’s salesforce is an important channel through which all products must pass.

We use this broader definition of channel because there needs to be symmetry of motivation across the entire chain of entities that add value to the product on its way to the end customer. If your product does not help all of these entities do their fundamental job better—which is to move up-market along their own sustaining trajectory toward higher-margin business—then you will struggle to succeed. If your product provides the fuel that entities in the channel need to move toward improved margins, however, then the energy of the channel will help your new venture succeed.

Disruption causes others to be disinterested in what you are doing. This is exactly what you want with competitors: You want them to ignore you. But offering something that is disruptively unattractive to your customers—which includes all of the downstream entities that compose your channel—spells disaster. Companies in your channel are customers with a job to get done, which is to grow profitably.

Retailers and Distributors Need to Grow Through Disruption, Too

Retailers and distributors face competitive economics similar to those of the minimills we described in chapter 2. They need to keep moving up. If they don’t, and just sell the same mix of merchandise against competitors whose costs and business models are similar, margins will erode to the minimum sustainable levels. This need to move up-market is a powerful, persistent disruptive energy in the channel. Harnessing it is crucial to success.

If a retailer or distributor can carry its business model up-market into higher-margin tiers, the incremental gross margin falls almost directly to the bottom line. Hence, innovating managers should find channels that will see the new product as a fuel to propel the channel up-market. When disruptive products enable the channel to disrupt its competitors, then the innovators harness the energies of the channel in building the disruption.

When Honda began its disruption of the North American motorcycle market with its small, cheap Super Cub motorized bicycle, the fact that it could not get Harley-Davidson motorcycle dealers to carry Honda products was good news, not bad—because the salespeople in the dealerships always would have been able to make higher commissions by choosing to sell Harleys instead of Hondas. Honda’s business took off when it began to distribute through power equipment and sporting goods retailers, because it gave those retailers a chance to migrate toward higher-margin product lines. In each of the most successful disruptions we have studied, the product and its channel to the customer formed this sort of mutually beneficial relationship.

This is an important reason why Sony became such a successful disruptor. Discount retailers such as Kmart, which had no after-sale capability to repair vacuum tube–based electronic products, were emerging at the same time as Sony’s disruptive products. Solid-state radios and televisions constituted the fuel that enabled the discounters to disrupt appliance stores. By selecting a channel that had up-market disruptive potential itself, Sony harnessed the energies of its channel to promote and position its products.

The fuel that a disruptive company provides to its channel will become spent, meaning that getting your products in the channels that stand to benefit the most is a perpetual challenge. This happened to Sony. After the discounters had driven the appliance stores out of the consumer electronics market and the products were being sold by equal-cost discount retailers, margins on those products eroded to subsistence levels. Consumer electronics no longer provided the fuel that the discounters needed to move up-market. Consequently, they de-emphasized electronics, gradually leaving them to be sold in even lower-cost retailers such as Circuit City and Best Buy. The discount department stores had to then look to clothing, which was the next fuel that would enable them to move up and compete against higher-margin retailers again.

Value-added distributors or resellers face the same motivations as retailers. As an example, Intel and SAP established a joint venture called Pandesic in 1997 to develop and sell a simpler, less-expensive version of SAP’s enterprise resource planning (ERP) software to small and medium-sized businesses—a new-market disruption.9 SAP’s products historically had been targeted at huge enterprises, which would ante up several million dollars to purchase the software, and another $10 million to $200 million to implement it. The sale and implementation of SAP’s products was largely done by its channel partners—implementation consultants such as Accenture, which experienced tremendous growth riding the ERP wave.

Pandesic’s managers decided to take their lower-priced, easier-to-implement ERP package to market through the same channel partners. But when the IT implementation consultants had to choose whether to spend their time selling huge multimillion-dollar SAP implementation projects to global corporations or selling lower-ticket Pandesic software and straightforward implementation projects to small businesses, how would you expect them to expend their energy? Naturally, they pushed big-ticket SAP product implementations that helped them make the most money given their size and cost structure. There was no energy for Pandesic’s disruptive product in the channel that Pandesic chose, and the venture failed.

A company’s own salesforce will react the same way, especially if they work on commission. Every day salespeople need to decide which customers to call on, and which they will not call on. When they are with customers, they must decide which products they will promote and sell, and which they will not mention. The fact that they are your own employees doesn’t matter much: Salespeople can only prioritize those things that it makes sense for them to prioritize, given the way they make money. Rarely will people who sell a company’s mainstream products on the sustaining trajectory be successful in pushing the disruptive ones. It is foolish to give them a special financial incentive to push the disruptive products, because that would take their eye off their critical responsibility of selling the most profitable products on the sustaining trajectory. Disruptive products require disruptive channels.

Customers as Channels

For materials and components manufacturers, the end-use products constitute an important entity in their channel. In a similar way, service providers who use a product in order to deliver their service are the product’s channel to the end-use customer. For example, computer makers such as Compaq and Dell Computer constitute the “channel” by which Intel’s microprocessors reach an important market. The improvements in Intel’s microprocessor have been the fuel propelling makers of desktop machines up-market so that they can continue to compete against higher-cost computer makers such as Sun.

The same situation exists in service businesses. Just as lower-performing products can take root in simple applications and then get disruptively better, so too technological progress often enables less-skilled service providers to disrupt more highly trained and expensive providers above them. In a way that is analogous to Intel’s relationship with Dell, it is the potentially disruptive service providers that constitute the channel for the companies providing the enabling disruptive technology.

Let us illustrate the importance of fueling a disruptive channel by visiting health care again. In this industry today, many physicians are in a dogfight similar to that of the steel minimills. They are locked in a price-driven struggle against other physicians’ practices and the companies that reimburse for the cost of care, working ever harder to make attractive income. A major health care equipment company has begun launching a series of disruptive products that will help office-based caregivers to move disruptively upward—to pull into their own practices procedures that historically had to be referred to more expensive outpatient clinics.

One example is in diagnosing and resolving colon disorders. To date, if a patient appeared to have a possible lesion or tumor in the colon, the physician would perform a colonoscopy in a relatively expensive clinic or hospital. Threading the flexible scope through a serpentine colon requires the skill of a very capable specialist. If the colonoscopy revealed a problem, then the patient would be referred to an even higher-cost surgeon, who would operate to correct the problem in an even higher-cost hospital. This company is introducing a technology that is much easier to use and that will enable the less-specialized diagnosing physicians to perform these procedures safely and effectively right in their offices—and thereby to pull into the cost structure of their office value-added procedures that historically could only be done in more expensive channels.

This device could be marketed as a sustaining innovation to the specialists who already have mastered the difficult-to-use traditional scopes. You can imagine what the physician would ask the salesperson: “Why do I need this? Does it allow me to see better or do more than what I have right now? Is the scope cheaper? Won’t this thing here break?” This is a sustaining-technology conversation.

If the company marketed this as a disruptive technology enabling less-specialized physicians to do this procedure in their offices, however, the physician would likely ask, “What will it take to get trained on this thing?” This is a disruptive conversation.

What kinds of customers will provide the most solid foundation for future growth? You want customers who have long wanted your product but were not able to get one until you arrived on the scene. You want to be able to easily delight these customers, and you want them to need you. You want customers whom you can have all to yourself, protected from the advances of competitors. And you want your customers to be so attractive to those you work with that everyone in your value network is motivated to cooperate in pursuing the opportunity.

The search for customers like this is not a quixotic quest. These are the kinds of customers that you find when you shape innovative ideas to fit the four elements of the pattern of competing against nonconsumption.

Despite how appealing these kinds of customers appear to be on paper, the resource allocation process forces most companies, when faced with an opportunity like this, to pursue exactly the opposite kinds of customers: They target customers who already are using a product to which they have become accustomed. To escape this dilemma, managers need to frame the disruption as a threat in order to secure resource commitments, and then switch the framing for the team charged with building the business to be one of a search for growth opportunities. Carefully managing this process in order to focus on these ideal customers can give new-growth ventures a solid foundation for future growth.

Notes

1. Economists have great language for this phenomenon. As the performance of a product overshoots what customers are able to utilize, the customers experience diminishing marginal utility with each increment in product performance. Over time the marginal price that customers are willing to pay for an improvement comes to equal the marginal utility that they receive from consuming the improvement. When the marginal increase in price that a company can sustain in the market for an improved product approaches zero, it suggests that the marginal utility that customers derive from using the product also is approaching zero.

2. We stated earlier that few technologies are intrinsically sustaining or disruptive in character. These are extremes in a continuum, and the disruptiveness of an innovation can only be described relative to various companies’ business models, to customers, and to other technologies. What the transistor case illustrates is that attempting to commercialize some technologies as sustaining innovations in large and obvious markets is very costly.

3. Figure 4-2 was constructed from data provided by the American Heart Association National Center. Because these data measure only those procedures performed in hospitals, angioplasty procedures that were performed in outpatient and other nonhospital settings are not included. This means that the angioplasty numbers in the chart are underestimated, and that the underestimation becomes more significant over time.

4. There are many other examples of this, in addition to those cited in the text. For example, full-service stock brokers such as Merrill Lynch continue to move up-market in their original value network toward clients of even larger net worth, and their top and bottom lines improve as they do so. They do not yet feel the pain that they ultimately will experience as the online discount brokers find ways to provide ever-better service.

5. See Clark Gilbert and Joseph L. Bower, “Disruptive Change: When Trying Harder Is Part of the Problem,” Harvard Business Review, May 2002, 94–101; and Clark Gilbert, “Can Competing Frames Co-exist? The Paradox of Threatened Response,” working paper 02-056, Boston, Harvard Business School, 2002.

6. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, “Choice, Values, and Frames,” American Psychologist 39 (1984): 341–350. Kahneman and Tversky published prodigiously on these issues. This reference is simply an example of their work.

7. The phenomenon of threat rigidity has been examined by a number of scholars, notably Jane Dutton and her colleagues. See, for example, Jane E. Dutton and Susan E. Jackson, “Categorizing Strategic Issues: Links to Organizational Action,” Academy of Management Review 12 (1987): 76–90; and Jane E. Dutton, “The Making of Organizational Opportunities—An Interpretive Pathway to Organizational Change,” Research in Organizational Behavior 15 (1992): 195–226.

8. Arthur Stinchcombe has written eloquently on the proposition that getting the initial conditions right is key to causing subsequent events to happen as desired. See Arthur Stinchcombe, “Social Structure and Organizations,” in Handbook of Organizations, ed. James March (Chicago: McNally, 1965), 142–193.

9. Clark Gilbert, “Pandesic—The Challenges of a New Business Venture,” case 9-399-129 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2000).